An animal’s behavior can affect its risk of infection, but it is not well understood how behavior affects microbiome composition. The aquatic crustacean Daphnia exhibits genetic variation in the extent to which it browses in the sediment at the bottoms of ponds. We show that this behavior affects the Daphnia microbiome, indicating that genetic variation among individuals may affect microbiome composition and the movement of bacteria in different environments.

KEYWORDS: behavioral ecology, host-microbiome interactions

ABSTRACT

In many organisms, host-associated microbial communities are acquired horizontally after birth. This process is believed to be shaped by a combination of environmental and host genetic factors. We examined whether genetic variation in animal behavior could affect the composition of the animal’s microbiota in different environments. The freshwater crustacean Daphnia magna is primarily planktonic but exhibits variation in the degree to which it browses in benthic sediments. We performed an experiment with clonal lines of D. magna showing different levels of sediment-browsing intensity exposed to either bacteria-rich or bacteria-poor sediment or whose access to sediments was prevented. We found that the bacterial composition of the environment and genotype-specific browsing intensity together influence the composition of the Daphnia-associated bacterial community. Exposure to more diverse bacteria did not lead to a more diverse microbiome, but greater abundances of environment-specific bacteria were found associated with host genotypes that exhibited greater browsing behavior. Our results indicate that, although there is a great deal of variation between individuals, behavior can mediate genotype-by-environment interaction effects on microbiome composition.

IMPORTANCE An animal’s behavior can affect its risk of infection, but it is not well understood how behavior affects microbiome composition. The aquatic crustacean Daphnia exhibits genetic variation in the extent to which it browses in the sediment at the bottoms of ponds. We show that this behavior affects the Daphnia microbiome, indicating that genetic variation among individuals may affect microbiome composition and the movement of bacteria in different environments.

INTRODUCTION

Every multicellular organism is colonized by a community of microorganisms: its microbiota (1). The host provides a habitat for a complex and dynamic consortium of microorganisms, many of which have fundamental influences on the host’s well-being. A central concern in both infectious disease epidemiology and in studies of host-associated microbial community ecology is the transmission of microbes between host individuals and between hosts and the environment. Many bacterial assemblages are transmitted from host mother to offspring (2) or within social groups (3), but the diversity of microbiota typically changes over time depending on the microbes available in the environment (4, 5). In some cases, environmentally acquired microbes are even essential for the completion of postembryonic development (6, 7). Thus, microbes from the environment can be co-opted as part of the microbiota or can affect host health during a transient occupation (8).

Environmental effects on microbiota community structure have been extensively documented (9, 10), and studies on model organisms have started to shed light on the relative importance of environmental and host genetic factors in determining microbiota composition (11, 12). Recently, the focus has been moving toward a better understanding of the mechanisms of bacterial acquisition from the environment. Host genetics have been shown to play a role in the establishment of microbial associations through microbial recognition, immune selection, and determination of the biochemical niche (12). Importantly, these processes select microbes after the host has come in contact with bacterial communities in the environment. The initial encounter may be a key phase of the host’s colonization by microbes. If host genetics influence interaction with the environment, for example, through the expression of behavioral variation, it may influence the initial encounters with environmental bacteria and thus affect the composition of the host microbiota.

Many animals utilize different habitats according to behavioral strategies collectively termed habitat selection. If habitats differ in their microbial communities, host behavior influencing habitat choice and the microbiome may influence each other. Hosts may have evolved strategies to ensure or avoid encounters with beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms. Avoidance behaviors of harmful bacteria are well documented, and behavior is considered one of the first lines of defense against infectious disease. For example, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans actively avoids pathogenic bacteria, and the genetic determinants of this behavior have been worked out (13). The opposite case, where a host’s behavior is involved in the acquisition of beneficial bacteria from the environment, has received less attention, despite speculation about the role of human behaviors such as outdoor play in preventing autoimmune diseases (14). The overall effects of host habitat choice behavior on microbiome composition have not, to our knowledge, been explored in any system. An analysis of natural genetic variation in behavioral traits potentially influencing microbiota acquisition is therefore timely (15). If variation in behavior affects the composition of the host’s microbial community, then behavior could underlie some genotype-environment interaction effects on microbiota. The goal of this study was to examine the effect of genetic variation in host behavior on microbiota composition in different environments using the freshwater planktonic crustacean Daphnia magna.

Recently, it was shown that the D. magna microbiota plays a major role in host fitness (16), that both host clonal line and environmental factors are determinants of microbiota community structure (17), and that genotype-specific microbiomes can mediate daphnids’ adaptive traits (18). However, little is known about the mechanisms by which the host acquires the microbiota from the environment. A specific behavior, termed sediment browsing, mediates the interaction between D. magna and bottom sediments of ponds and lakes (19, 20). During browsing, the animals swim along the sediment surface, stirring up particles, and then ingest the particles by filter feeding. Besides representing valuable food reservoirs, sediments are likely important environmental sources of bacteria. Therefore, the physical contact with the sediments resulting from browsing might present both disease risks and benefits from increased contact with bacteria. Previous work found evidence of genetic variation for the levels of browsing activity in D. magna (21).

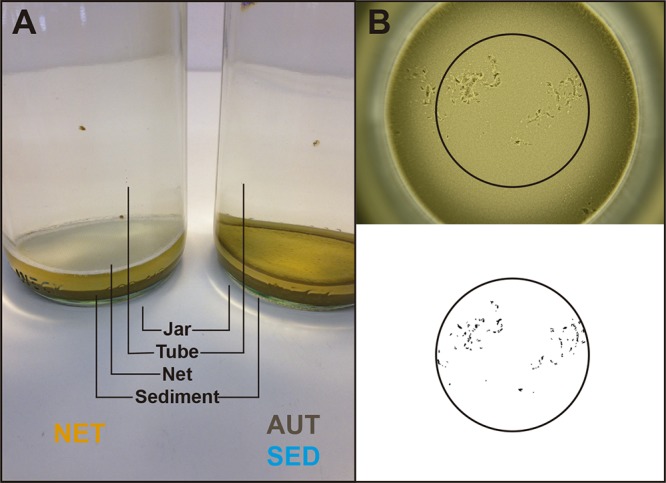

We performed a laboratory experiment in which we analyzed the browsing behavior and microbiota of 12 genetically distinct D. magna clones allowed to browse in sediment. The animals were exposed to three different treatment conditions, where they had access to either (i) previously autoclaved or (ii) untreated (“natural” and therefore microbe-rich) sediments or (iii) where their access to natural sediment was prevented (Fig. 1A). This setup amounts to an external manipulation of the behavior that mediates the acquisition of environmental microbiota, meaning it allows us, to some extent, to isolate the effect of genotype-specific behavior from other traits that vary between genotypes.

FIG 1.

Experimental set-up and browsing behavior assay. (A) The jars used in the experiment had a bottom layer of fine loess and contained two animals each; the animals were prevented from browsing on untreated sediments by a net placed 5 mm above the sediment surface (NET, left) or were allowed to browse on autoclaved sediments (AUT) or untreated sediments (SED) (right). (B) Traces left by one animal browsing on a sediment surface for 30 min, and the same picture after processing for quantification of the browsing behavior.

To analyze both the browsing behavior of the animals and their microbiota, we placed two animals in each jar; of these pairs of animals, after 6 days of exposure to the different treatments, one animal was used to assay browsing behavior while the other was used for microbiota analyses. We hypothesized that D. magna clones exhibiting more intense browsing behavior would have more diverse microbiota in conditions where they had access to bacteria-rich sediment, whereas the microbiome would be less affected by the bacterial environment in genotypes that browsed less. In this experiment, we made no assumptions about whether bacteria found in the sediments were beneficial, harmful, or neutral for the host nor whether they colonized Daphnia stably or transiently; therefore, the patterns observed here could be applicable to studies of disease, microbiota, or general environmental microbial community dynamics. Our analysis illustrates how a behavioral trait can mediate the interplay between genetic and environmental variation in the establishment of host-microbe associations.

RESULTS

Browsing intensity, animal microbiota, and sediment bacteria.

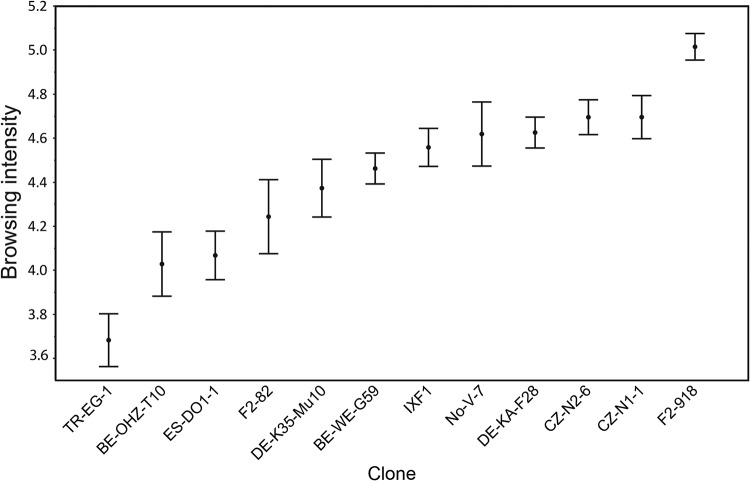

Consistently with a previous study (21), browsing behavior intensity varied among Daphnia clones (Fig. 2). Clone and treatment, but not their interaction, had a significant effect on browsing behavior (analysis of variance: clone, F = 12.717, df = 11, P < 0.0001; treatment, F = 4.100, df = 2, P = 0.018; clone by treatment interaction, F = 1.274, df = 22, P = 0.193). The average browsing intensity of animals from the prevented exposure to untreated sediment (NET) treatment was lower than that of animals in the exposure to untreated sediments (SED) and exposure to autoclaved sediment (AUT) treatments (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The total phenotypic variance for browsing behavior explained by clone, after controlling for the treatment effect, corresponded to 36.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.2% to 55.3%; P = 0.0002). Clone but not treatment had a significant effect on body size, so we assume that access to (and type of) sediment did not substantially affect nutrition and growth over the time frame of the experiment (analysis of variance: clone, F = 8.08, df = 11, P < 0.001; treatment, F = 2.01, df = 2, P = 0.137; clone by treatment interaction, F = 1.43, df = 22, P = 0.103). Individual body size was uncorrelated with behavior (analysis of variance: F = 0.346, df = 1, P = 0.56) (see Fig. S2).

FIG 2.

Browsing intensity of 12 D. magna clones (means and SEMs). Browsing intensity was defined as the log10 of the area of the browsing traces left by individual replicate animals browsing on a sediment surface for 30 min (see Fig. 1).

A total of 370 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were found among the animal samples; of these, 318 were found in less than 10% of samples. (see Fig. S3A to C for taxonomic heat trees of OTUs with presence/absence information) (22). Consistently with multiple previous studies of Daphnia microbiota (23–26), the most abundant bacterial species was a single OTU (OTU_1) of Limnohabitans sp. (Betaproteobacteria, Comamonadaceae), with a mean relative abundance across all clones of 0.39 (standard error of the mean [SEM], 0.02). Interestingly, a second type of Limnohabitans (OTU_2) was a dominant OTU only in the three clones originating from clones bred in the laboratory as part of a genetic breeding design (quantitative trait loci [QTL] panel, 0.32 mean relative abundance among individuals of clones IXF1, F2-82, and F2-918; 0.0016 mean relative abundance in remaining clones). As expected, the sediment used in the SED treatment had much higher bacterial species richness than that in the AUT treatment (see Fig. S4).

Effects of treatment and clone on alpha diversity.

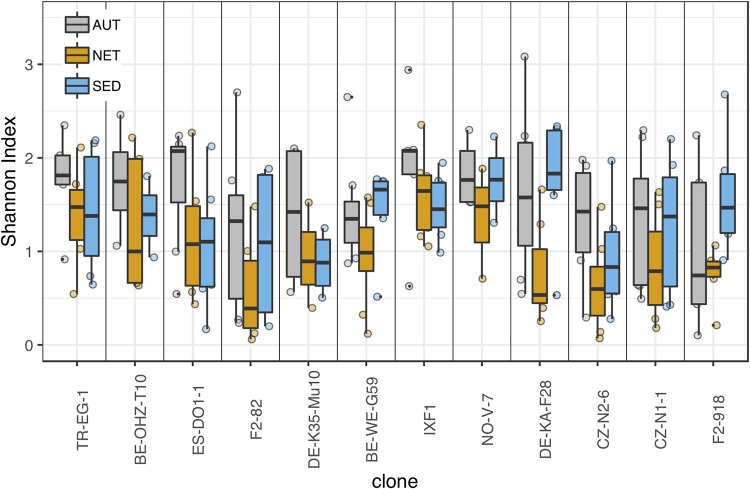

Both Daphnia clone and treatment, but not their interaction, had significant effects on the Shannon and inverse Simpson alpha diversity indices (Table 1). For further analyses, we focused on the Shannon index, because it takes into account not only species richness but also evenness (with additional species given more weight as they become more abundant). The Shannon index displayed no significant effect of processing batch (DNA extraction and amplification) (df = 5, F = 1.42, P = 0.22). Shannon diversity estimates for the 12 clones arranged in order of increasing average browsing intensity and the three groups (AUT, NET, and SED) are shown in Fig. 3 (species richness and inverse Simpson indices are shown in Fig. S5A and B). Unexpectedly, the highest average alpha diversity in most clones (9/12) was observed in the AUT treatment group despite their exposure to less-diverse sediment than the SED group. Therefore, the diversity of animal microbiota does not directly reflect the diversity of bacteria in the environment.

TABLE 1.

Results of analyses of variance of different alpha diversity indicesa

| Variable | Richness |

Shannon |

Inverse Simpson |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F value | df | P value | F value | df | P value | F value | df | P value | |

| Clone | 0.40 | 10 | 0.944 | 2.43 | 10 | 0.00997 | 1.98 | 10 | 0.0383 |

| Treatment | 4.91 | 2 | 0.00842 | 12.21 | 2 | 0.0001 | 13.25 | 2 | 0.0001 |

| Clone:treatment | 0.75 | 20 | 0.770 | 0.78 | 20 | 0.734 | 0.65 | 20 | 0.8124 |

All treatments are included; clone NO-V-7 is excluded.

FIG 3.

Microbiota diversity (Shannon index) of Daphnia clones under three different treatment conditions (AUT, NET, and SED). AUT, exposure to autoclaved sediment; NET, prevented exposure to untreated sediment; SED, exposure to untreated sediments. Clones are arranged left to right by increasing average clone browsing intensity.

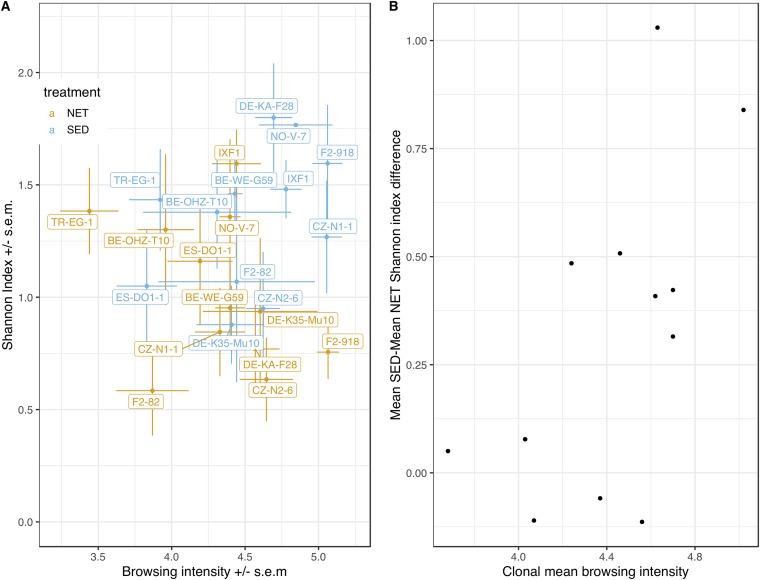

To specifically investigate the effect of direct access to the same bacterium-rich sediment, we compared the NET and SED treatment groups’ diversity as a function of clonal average behavior in each group (Fig. 4A). The difference in mean Shannon diversity between SED and NET animals was greatest at the highest average clonal level of browsing intensity (linear regression P = 0.055) (Fig. 4B). A similar tendency was seen when the browsing intensity of each individual’s jar mate was used as the proxy for individual behavior (see Fig. S6). Shannon diversity significantly depended on the interaction between treatment and clonal average browsing intensity in a linear mixed-effects model with clone included as a random effect (Table 2); the same was true when treatment-specific clonal average behavior was used as the behavior proxy but not when individual jar mate behavior was used (see Table S1).

FIG 4.

Average browsing intensity and average microbiota diversity in the NET and SED treatments. (A) Average clone browsing intensity and average clone microbiota diversity in the NET and SED treatments. Average browsing intensities were calculated based on samples whose jar mates passed the sequence quality control (N = 214) (Table 4). (B) Average clone browsing intensity and the difference between average Shannon diversity in the SED treatment and average diversity in the NET treatment. Here, average browsing intensities were calculated based on the complete set of samples (N = 228, i.e., all assayed jar mates). Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

TABLE 2.

Effect on Shannon indexa

| Variable | numDFb | denDFc | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 129 | 270.12 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | 1 | 129 | 12.26 | 0.0006 |

| Clone average behavior | 1 | 9 | 0.275 | 0.613 |

| Clone average size | 1 | 9 | 2.568 | 0.144 |

| Treatment:clone average behavior | 1 | 129 | 4.677 | 0.0324 |

| Treatment:clone average size | 1 | 129 | 0.0980 | 0.755 |

NET and SED treatments only, all clones included. Linear mixed-effects model with treatment, clonal average browsing intensity, and clonal average size as fixed effects and clone as random effect.

numDF, numerator degrees of freedom.

denDF, denominator degrees of freedom.

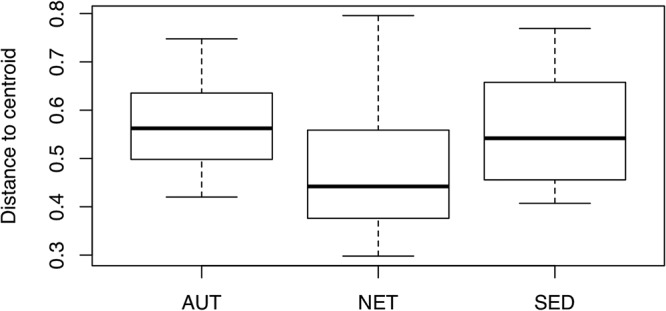

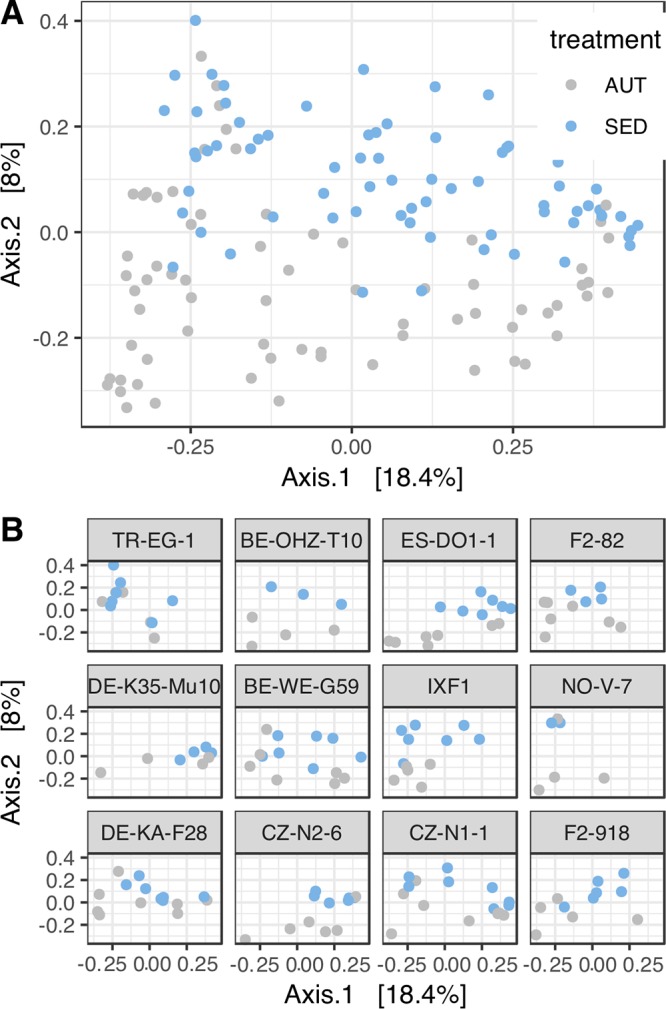

Community composition and acquisition of bacteria from sediment.

To examine shifts in bacterial community composition in response to environmental treatments, we Hellinger transformed the bacterial abundances by taking the square root of the relative abundance of each taxon in each sample to reduce the influence of rare taxa and then calculated pairwise Bray-Curtis distances between samples. The average distance to the centroid (dispersion) was lower in the NET group than in the AUT and the SED groups (Fig. 5), suggesting that access to sediment increases the variability of the microbiota regardless of the composition of the sediment. To see whether the different sediments resulted in systematically different microbiota compositions, we excluded the NET group and performed a principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 6). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA; adonis) analysis stratified by processing batch showed that both treatment and clone had significant effects (treatment, R2 = 0.05, P = 0.001; clone, R2 = 0.16, P = 0.001) but not their interaction (treatment by clone interaction, R2 = 0.07, P = 0.63). However, clones also showed significant differences in dispersion (P < 0.001). The R2 values suggest that most variance in the data set is not explained by these two factors, meaning that clonal and environmental factors have small—albeit detectable—effects on composition.

FIG 5.

Within-group dispersion of community similarity. The median distance to the centroid is lower in the NET treatment group than in the others (permutation test of multivariate dispersion P < 0.0001, 999 permutations), meaning that NET communities are less variable than AUT or SED microbiotas.

FIG 6.

Similarity of bacterial community composition in the AUT and SED treatments. (A) First and second axes of a principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial community composition based on Hellinger-transformed Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. (B) First and second axes of a principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial community composition by Daphnia clone.

Having confirmed that differences in the sediment environment resulted in differences in animal microbiota composition, we next explored the extent to which environment-specific bacteria contributed to these differences. We used the implementation of DESeq2 in phyloseq to determine which bacteria were significantly more present in natural sediment than in autoclaved sediment (n = 3 each). One hundred fifteen OTUs were calculated to be significantly differentially present between the two sediment types (see Table S2); of these, 48 had at a log2-fold increase of at least 8 in natural sediment compared to that in autoclaved sediment. We refer to these as natural-sediment-derived taxa. The 8-fold threshold was chosen based on inspecting the data; similar results were seen when sediment-derived bacteria were defined by a log2-fold change of 5 or 10 (see Fig. S7). Only one of these OTUs was found in a majority of animals, and the median number of animals in which a given OTU was found was 6.5. We therefore concluded that animals likely acquired environmental bacteria randomly rather than selectively from the environment. Accordingly, we looked at the total relative abundance of reads from all natural-sediment-derived bacteria in each individual.

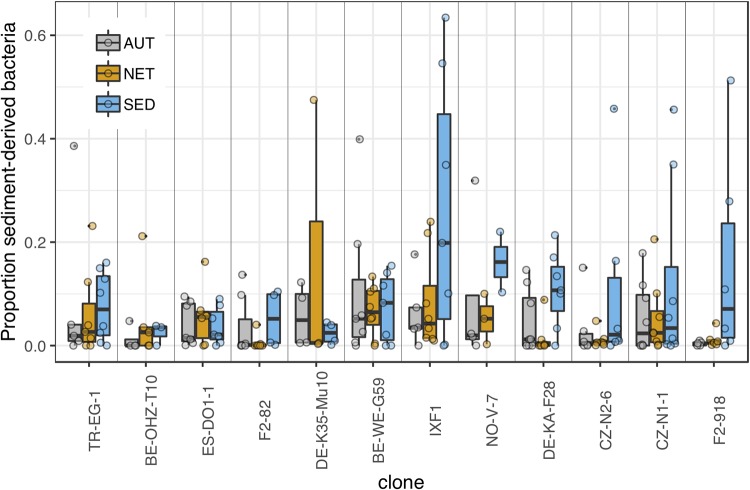

The relative abundance of natural-sediment-derived bacteria was generally low in both the AUT and NET treatment groups and increased with browsing intensity in the SED treatment group (Fig. 7), with a significant interaction effect between treatment and clonal average browsing intensity (Table 3). Treatment-specific clonal average behavior showed the same significant interaction effect with treatment, but the interaction effect was not significant when jar mate behavior was used as the behavior proxy. Among the set of clones examined here, an appreciably high relative abundance of sediment-derived bacteria was detectable mainly in clones with a browsing intensity index higher than a mean of 4.4 (clones IXF1, NO-V-7, DE-KA-F28, CZ-N2-6, CZ-N1-1, and F2-918). The mean relative abundance of sediment-derived bacteria in the SED treatment in the pooled animals from these clones was 0.14 (SEM, 0.026), whereas it was 0.048 (SEM, 0.0097) in the lower-browsing clones. Across all clones in the AUT and NET treatment groups, the average relative abundance of sediment-derived bacteria was 0.051, nearly identical to that of the low-browsing clones under the SED conditions.

FIG 7.

Analysis of sediment-derived bacteria. Proportions of sediment-derived bacteria in the microbiota of animals from AUT, NET, and SED treatments. Sediment-derived bacteria were identified by comparing autoclaved and untreated sediment samples (log2-fold increase of at least 8 in natural sediment compared to that in autoclaved sediment). Clones are arranged left to right by increasing average clone browsing intensity.

TABLE 3.

Effect on relative abundance of sediment-derived bacteriaa

| Variable | numDFb | denDFc | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 198 | 53.999 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | 2 | 198 | 6.500 | 0.0018 |

| Clone average behavior | 1 | 10 | 0.490 | 0.4998 |

| Treatment:clone average behavior | 2 | 198 | 4.185 | 0.0166 |

All treatments and all animals included. Linear mixed-effects model with treatment and clonal average browsing intensity as fixed effects and clone as random effect.

numDF, numerator degrees of freedom.

denDF, denominator degrees of freedom.

DISCUSSION

Our results have several implications for studies of animal-associated microbiota in diverse environmental settings. First, we confirm the intuition that environmental sources of bacteria affect the diversity of animal microbiota, but not because more diverse environments always create more diverse microbiota; rather, the animals we exposed to the less species-rich autoclaved sediments had higher overall diversity in their microbiota than those exposed to untreated bacterial species-rich sediment. We hypothesize that this might be due to competitive interactions between Daphnia microbiota and the particular microbes found in these sediments. The untreated sediments may contain bacteria that can outcompete multiple OTUs of “native” preexisting Daphnia microbiota. If this were the case, then browsing in sediment could have multiple opposing effects on overall microbiota diversity: on the one hand, it would bring daphnids into contact with more diverse bacteria, but on the other hand, those bacteria could reduce existing microbiota diversity. In the NET treatment, animals might be exposed to some sediment-derived bacteria in the water column but lack access to the full diversity of bacteria in the sediment. An experiment designed to explicitly test this hypothesis would be required to determine whether there are competitive interactions between exogenous sediment-derived bacteria and those typically carried by Daphnia in the laboratory; it would also be interesting to see how these competitive effects interact with early colonization events in young Daphnia.

We also saw that having access to either sediment increased the variability of community composition as measured by multivariate dispersion. These results suggest that having access to multiple habitats with different bacterial communities can affect the diversity and composition of an animal’s microbiota. Therefore, fine-scale heterogeneity in a host’s habitat might be a relevant aspect to take into account when examining effects of environment on animal microbiota. This is especially important when considering ecological immunology, because disease-causing bacteria in the environment may cause short-term risk but also long-term fitness benefit via processes such as immune priming (27, 28).

Our data further suggest that the diversity of Daphnia-associated microbiota in a particular environment may to some extent be mediated by genotype-specific sediment browsing intensity. This was apparent as the net barrier made the greatest difference in microbial alpha diversity in high-browsing host clones. However, this effect may be partially obscured by several factors: the hypothesized competitive exclusion effects we allude to above and also non-behavior-related host genotype effects on microbiota diversity. While host genotype had an effect on microbial diversity, the highest- and lowest-browsing clones in our study had similar microbial alpha diversity overall. The only way to conclusively determine that differences between the microbiotas of different genotypes are mediated by host behavior independently of other host traits would be to genetically manipulate behavior on an otherwise identical genetic background; we approximate this in our experiment with the treatment where Daphnia are blocked from sediment browsing, contrasted with the treatment where they are allowed to browse freely. Our cautious conclusions about the effect of behavior on the microbiome are based on examining the contrast between these treatments within each genotype, not based on the observation of genotype-dependent differences alone. It was only in evaluating the difference between presence and absence of the barrier that an effect of browsing on diversity was seen. We conclude that the effect of environmental bacteria on host-associated microbiota is not additive. The clearest effect of environmental bacteria on host-associated microbiota was not on alpha diversity but on the relative abundances of certain taxa.

Clones with low average browsing intensity had no greater amount of sediment-specific bacteria than animals exposed to autoclaved sediment or prevented from browsing, whereas those with high browsing intensity reached >60% of reads from environment-derived bacteria in some individuals. While many studies of animal microbiota rightly concern themselves with distinguishing between truly “host-associated” microbiota versus “transient environmental” microbiota, these results raise the possibility that the amount of environmental microbes found in association with an animal could itself be a host-genotype-specific feature of the microbiome.

Another key question is whether browsing behavior affects community composition by simple exposure to more colonizing bacteria or by more frequent replenishment of bacterial taxa that would not otherwise persist in association with the host. For example, browsing frequently enough may replenish bacteria that would otherwise be lost when the animal molts. In Drosophila, some functionally important bacteria do not persist at the replacement rate within the host and must be continuously replenished from the environment (29). It is not known how widespread such situations are in nature or whether a fraction of the microbiome that requires continual environmental replenishment is missing in microbiome surveys carried out under “cleaner” laboratory conditions. Conversely, the hosts’ recent behavior should be considered a potential source of variability when sampling animal microbiomes in nature, and behavior as an interface between animals and environments should be considered when examining host traits that affect host-microbe interactions. In this study, we made no assumptions about the types of interactions between the sediment-associated bacteria and the Daphnia but still were able to demonstrate a link between the environmental and host-associated microbiome.

It would also be interesting to investigate whether carriage of bacteria on Daphnia from the sediment into the water column affects bacterial dynamics in the larger environment; previous studies have shown that movement of Daphnia between benthic and limnetic environments represents a mechanism of bacterial dispersal in the environment (30). Studies using classification methods more sensitive than 16S-based taxonomy may be necessary to unambiguously distinguish and assign sources to different bacteria.

Conclusion.

We show that at least some characteristics of host-associated microbial community composition result from genotype-by-microhabitat interactions, specifically, ones resulting from genotype-specific variation in behavior. We show this using an experimental treatment that externally manipulated behavior, but genetically manipulating behavior to confirm these results would be a natural next step when the molecular tools to do so become available. Behavior could thus be considered a genetic factor that shapes microbial exposure in a given environment. Overall, these results provide further evidence that environment, behavior, genetics, disease risk, and microbial community composition are interrelated in potentially complex ways. Our observations indicate a need for more integrative eco-immunology studies, in which the interfaces between behavioral ecology, microbial community ecology, and evolution of immune function are explored. Studies can take advantage of the experimental tractability of the Daphnia-microbiota system to further investigate these relationships in mechanistic detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of the experiment.

In this study, we combined the analysis of animals with constitutive (genetic) differences in browsing behavior with manipulations of the environment that affected animals’ access to the sediments. Animals were either exposed to natural sediment, to autoclaved sediment, or to natural sediment blocked by a permeable net barrier (Fig. 1A). To analyze both the browsing behavior of the animals and their microbiota, we placed two animals in each jar; of these pairs of animals, after 6 days of exposure to the different treatments, one animal was used to assay browsing behavior while the other was used for microbiota analyses.

Experimental animals.

D. magna reproduces by cyclical parthenogenesis. Clonal populations can be generated and propagated in the laboratory through asexual reproduction. Here, we refer to such genetically identical individuals as “replicates” or “animals” while we refer to different genetic lines as “clones.” In this study, we used 12 D. magna clones from our stock collection, originating from different populations (Table 4). The animals were propagated from stock cultures maintained in the laboratory under standardized conditions and without any effort to modify their microbiota. The browsing behavior of these clones has been assessed before (21) and was shown to differ among genotypes.

TABLE 4.

Names, numbers of individual replicates included in the microbiota analyses in the three treatments (AUT, NET and SED), and origin information of the 12 Daphnia magna clones used in this study

| Source and clone ID |

Na |

Country | Latitude | Longitude | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT | NET | SED | ||||

| D. magna diversity panelb | ||||||

| BE-OHZ-T10 | 4 | 5 | 3 | Belgium | 50°50′00″N | 4°39′00″E |

| CZ-N1-1 | 8 | 8 | 8 | Czech Rep. | 48°46′31.14″N | 16°43′24.70″E |

| CZ-N2-6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | Czech Rep. | 48°46′31.14″N | 16°43′24.70″E |

| DE-K35-Mu10 | 4 | 3 | 4 | Germany | 48°12′23.93″N | 11°42′34.98″E |

| DE-KA-F28 | 8 | 7 | 7 | Germany | 50°56′02″N | 6°55′41″E |

| ES-DO1-1 | 7 | 6 | 7 | Spain | 36°58′42.1″N | 6°28′39.5″W |

| TR-EG-1 | 5 | 7 | 8 | Turkey | 39°49′25″N | 32°49′50″E |

| BE-WE-G59 | 7 | 8 | 7 | Belgium | 51°04′04″N | 3°46′25″E |

| No-V-7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Norway | 67°41′13.06″N | 12°40′19.09″E |

| D. magna QTL panelc | ||||||

| IXF1 (F1 clone) | 5 | 8 | 7 | |||

| F2-82 (F2 clone) | 7 | 7 | 4 | |||

| F2-918 (F2 clone) | 5 | 6 | 6 | |||

AUT, exposure to autoclaved sediment; NET, prevented exposure to untreated sediment; SED, exposure to untreated sediments.

A geographically diverse collection of clones maintained asexually in the laboratory since 2012.

An intercross F2 recombinant panel maintained asexually in the laboratory since 2006/2007.

D. magna reproduces mostly asexually, with male organisms being rare. Therefore, all animals used in this study were female. Prior to the experiment, every clone was propagated in individual replicates for three generations to minimize variation due to maternal effects. These animals were kept individually in 100-ml glass jars filled with 80 ml of ADaM (Daphnia medium [31]) randomly distributed within trays in incubators with a 16:8 light/dark cycle and constant temperature of 20°C. To establish every generation, the animals were isolated at 4 days old and fed daily with chemostat-grown green algae Scenedesmus sp.: 1 × 106 algae cells/animal until day 5, 2 × 106 until day 8, 2.5 × 106 until day 10, 3 × 106 until day 12, and 5 × 106 onwards. The animals were transferred to fresh medium when they were 12 days old and thereafter every day.

For the experiment, we used animals from the 4th generation of each of the 12 clones. These animals were kept in groups of 8 siblings belonging to one clutch of one mother. At 4 days old (±1 day), 6 animals from every clutch were randomly assigned in pairs to individual jars divided into the three different treatments (split brood design); each such jar containing a pair of animals was an experimental replicate. In total, we included in the experiment 540 animals (270 pairs) corresponding to 15 pairs of clone BE-OHZ-T10, 18 pairs of clones DE-K35-Mu10 and NO-V-7, 21 pairs of clone F2-918, and 24 pairs of each of the remaining clones. Variation in replicate numbers resulted from differences in the availability of female offspring at the time that the treatments were established.

Experimental design.

The experiment was conducted in cylindrical glass jars (height, 20 cm; diameter, 6.5 cm) (Fig. 1A) kept in cardboard boxes on shelves in a climate room (16:8 light/dark cycle at 20°C), loosely covered with transparent plastic film and top-illuminated with neon lights. In this way, light only entered the jars from the top. All the experimental jars were first filled with 400 ml of medium. Fifteen milliliters of a suspension of loess (fine silt) was then carefully deposited on the bottom using a serological pipette. The loess was previously collected from a soil stock from a pit near Biel-Benken, Switzerland. To prepare it for the experiment, the loess was suspended in water, passed through a 200-μm filter, and washed to remove very fine particles. After 2 days of sedimentation in the experimental jars, the loess formed a 1-cm layer at the bottom of the jar. Then, an acrylic tube (height, 21 cm; diameter, 5 cm) was inserted into the jars and kept in position with a plastic ring fixed to the opening of the jar, so that its lower end was positioned close to the sediment surface. In one treatment (NET), the acrylic tube was closed with a 500-μm net at the lower end (suspended 5 mm above the sediment surface) preventing animals from direct contact with the sediment (Fig. 1A, left). In the other two treatments (AUT and SED), the acrylic tubes had no net, so that the animals had free access to the sediment (Fig. 1A, right). In the AUT treatment, the loess was previously autoclaved, while in the SED and the NET treatments, the loess was left untreated (natural). After autoclaving, AUT sediment was handled in the same way as natural sediment, i.e., exposed to nonsterile medium and laboratory environment. After inserting the tubes, the jars were left undisturbed for 2 days before the animals were introduced in order to allow the sediment to settle. Immediately before the experiment, the sediments of three jars of each of the SED and the AUT treatments were sampled and frozen at −20°C; these sampled jars were not used further.

Two animals from the same clutch were carefully introduced into the inner tube of each jar. The 264 jars, each containing one pair of animals, were evenly distributed among the treatments and their positions in the incubator room were randomized. The animals remained in the experimental jars for 6 days. During this time, the animals were carefully fed twice daily with 2.5 × 106 algal cells. At day 6, all animals were collected, and one member of every pair was assigned to the behavioral assay (see below) and the other was frozen for later DNA extraction. Thirty-two pairs of animals were lost or damaged during the experiment and were excluded from further analyses. At the end of the experiment, 3 sediment samples from the NET treatment and 3 sediment samples from the AUT treatment were collected and frozen at −20°C.

Behavioral analysis.

The animals for the behavioral assay were transferred individually from the sediment jars to 100-ml glass jars filled with medium and kept in an incubator and fed daily with 5 × 106 algal cells. The behavior assay was conducted over 2 days when the animals were 12 to 14 days old, with all replicates for the different clone-by-treatment combinations evenly distributed across time. The behavior assay was performed as described previously (21). Briefly, we measured the traces left by individual replicate animals on a smooth surface layer of sediment (loess) at the bottom of tall cylindrical glass jars (20 cm tall, 6.5 cm diameter) (Fig. 1B) during 30 min. The sediment surface was photographed before animals were released (time zero), using a ring light to ensure uniform illumination. The jar was then transferred to a cardboard tube and illuminated from the top with a neon light, and one animal was introduced in each jar. After exactly 30 min, the animal was removed and the sediment surface was again photographed (time 1), in the same position and under the same light conditions. Using the software ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), the pictures were converted to gray scale and a central circular area was cropped to exclude shadows from the edge of the jar (Fig. 1B). Pictures were processed such that the browsing traces of the animals on the sediment surface resulted in black areas against a white background. Then, the number of black pixels was quantified. Pictures taken at time zero were used to correct the values calculated for the browsing traces when irregularities on the sediment surface were detected (i.e., in cases the picture of time zero was not entirely white). The pixel values were then log-transformed [log10(X + 1,000)]; 1,000 corresponds approximately to the number of pixels of one individual browsing trace. During the assay, four animals were accidentally damaged while handling and were excluded from the analyses. The jar mate counterparts of these individuals were still sequenced but were excluded from sequencing analyses in which individual jar mate behavior was used as the behavior proxy. The body lengths of the animals used for behavior analysis were measured after the behavioral assay.

The adjusted intraclass correlation coefficient for the browsing behavior (equivalent to broad sense heritability) was calculated with a linear mixed-effect model (LMM), with treatment as a fixed effect and clone as a random effect (R software package rptR developmental version [32]). Confidence intervals and statistical significance were calculated using parametric bootstrapping with 5,000 iterations and a randomization procedure with 5,000 permutations.

DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing.

The animals assigned to the microbiota analysis were transferred individually from the sediment treatment jars to 40 ml of autoclaved ADaM for approximately 2 h to dilute carryover of unattached bacteria. Then, the animals were transferred into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, the ADaM was removed, and the tubes were stored at −20°C until DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from single animals using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based protocol. The animals were ground with a sterile pestle in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes in a 10-mg/ml lysozyme solution and mixed at 850 rpm and 37°C for 45 min. Then, a 20-mg/ml solution of proteinase K was added and the tubes mixed at 850 rpm and 55°C for 1 h. After an RNase treatment (20 mg/ml) at room temperature for 10 min, a preheated 2× solution of CTAB was added and the tubes mixed at 300 rpm and 65°C for 1 h. After two rounds of chloroform isoamyl alcohol (CIA) purification (1 volume CIA; 8-min centrifugation at 12,0000 rpm and 15°C), a solution of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) and isopropanol was added to the DNA solution and the tubes were stored overnight at −20°C. The following day, DNA was purified by two rounds of 70% ethanol precipitation and suspended in water. The extractions were incubated at 4°C overnight and then stored at −20°C.

All DNA extractions were conducted over a period of 6 days with samples from the different clone-by-treatment combinations randomly distributed between the days and one reagent-only negative-control extraction included every day. DNA from the sediment samples and from one negative control was extracted on a different day using a commercial kit (PowerSoil DNA extraction kit, catalog number 12888-100; Mo Bio Laboratories).

We sequenced amplicons of the V3-V4 variable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene using the Illumina MiSeq platform. Amplicons were generated using NEBNext High Fidelity PCR Master Mix (catalog number M0541L; New England BioLabs) for 27 cycles in 25-μl reaction mixtures containing 3% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The primers used were 341F (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGA-3′) and 785R (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCAGA-3′) with Illumina adapter sequences and 0- to 3-bp random frameshifts. The PCR product was purified with AMPure beads at a 0.6× ratio of beads to PCR product, amplified for 9 cycles with Nextera XT v2 indexing primers, and purified again. Libraries were quantified with Qubit and quantitative PCR, normalized, and pooled, followed by additional bead purification to remove remaining short fragments before sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq (reagent kit v3, 300-bp paired-end reads). The same library pool was used for two MiSeq runs; after checking that there was no statistical difference in community composition between the runs (PERMANOVA [adonis] analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between samples, P = 0.394), the data from the two runs were merged using the default settings in phyloseq.

Sequence quality control.

Raw reads were quality controlled with FastQC (Babraham Institute, UK). Paired reads were merged (FLASH v1.2.9), primers trimmed (Cutadapt v1.5), and quality filtered (PRINSEQ-lite v0.20.4). OTU clustering including abundance sorting and chimera removal was performed using the UPARSE workflow (33). Only those OTUs represented by 5 or more reads in the run were included. Taxonomic assignment was performed using UTAX against the Greengenes v13/5 database. We analyzed samples with more than 5,000 total reads. This left 214 samples; numbers of replicates for each combination of variables are reported in Table 4.

Since individual Daphnia contain low bacterial biomass, we considered the issue of reagent contamination with bacterial DNA (34). Samples were processed in haphazard order, and so erroneous sequences originating from reagent contamination were expected to be distributed randomly and not confounded with any treatment or genotype. For our research question, we were interested in patterns of diversity and changes in composition in response to experimental factors rather than in the presence or absence of any particular strain. For all analyses, we first tested for processing batch effects and stratified the main analysis by batch if they were significant.

For statistical analyses in which host clone was a fixed effect, we excluded clone NO-V-7, since it did not have at least 3 replicates in each treatment; we included this clone in analyses where clone was treated as a random effect. We examined the effects of experimental factors on both overall diversity and the community composition of each animal’s microbiota using standard ecological diversity indices and ordination methods. To evaluate the effect of animal behavior on microbiota, we used as proxies for individual behavior either the mean browsing intensity index of the clone or the browsing intensity of the individual cohoused with the sequenced individual in the same jar (jar mate).

Analyses were carried out in R (3.4.3), using the packages phyloseq (1.22.3), vegan (2.4.6), plyr (1.8.4), dplyr (0.7.4), DESeq2 (1.10.1), nlme (3.1.131), lme4 (1.1.15), metacoder (0.3.0.1), and ggplot2 (2.2.1).

Data availability.

Sequence data are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive of the EBI under accession number PRJEB30308. Data tables, OTU sequences, and code used for analysis can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/amusheg/Daphnia-microbiota-behavior and in Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.g75r459.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniel Lüscher for designing the experimental jars, Jürgen Hottinger for laboratory support, and the Botanical Institute of the University of Basel for providing sediment. Illumina sequencing was performed at the Genetic Diversity Centre of the ETH Zürich. We also thank Aria Minder and Silvia Kobel for advice on library preparation.

This work was funded by an ERC advanced grant (268596-MicrobiotaEvolution).

A.A.M. and R.A. conceived the study and performed the experiment with input from D.E. R.A. performed behavioral assays and analysis. A.A.M. and R.A. prepared sequencing libraries. J.-C.W. performed quality control and OTU clustering of sequence data. A.A.M. analyzed sequencing data. A.A.M. and R.A. wrote the paper. D.E. and J.-C.W. revised the paper.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01547-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.McFall-Ngai M, Hadfield MG, Bosch TCG, Carey HV, Domazet-Loso T, Douglas AE, Dubilier N, Eberl G, Fukami T, Gilbert SF, Hentschel U, King N, Kjelleberg S, Knoll AH, Kremer N, Mazmanian SK, Metcalf JL, Nealson K, Pierce NE, Rawls JF, Reid A, Ruby EG, Rumpho M, Sanders JG, Tautz D, Wernegreen JJ. 2013. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funkhouser LJ, Bordenstein SR. 2013. Mom knows best: the universality of maternal microbial transmission. PLoS Biol 11:e1001631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tung J, Barreiro LB, Burns MB, Grenier JC, Lynch J, Grieneisen LE, Altmann J, Alberts SC, Blekhman R, Archie EA. 2015. Social networks predict gut microbiome composition in wild baboons. Elife 4:e05224. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Heilig HGHJ, Molenaar D, Kajander K, Surakka A, Smidt H, De Vos WM. 2009. Development and application of the human intestinal tract chip, a phylogenetic microarray: analysis of universally conserved phylotypes in the abundant microbiota of young and elderly adults. Environ Microbiol 11:1736–1751. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin H, Pei Z, Martinez KA, Rivera-Vinas JI, Mendez K, Cavallin H, Dominguez-Bello MG. 2015. The first microbial environment of infants born by C-section: the operating room microbes. Microbiome 3:59. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheesman SE, Neal JT, Mittge E, Seredick BM, Guillemin K. 2011. Epithelial cell proliferation in the developing zebrafish intestine is regulated by the Wnt pathway and microbial signaling via Myd88. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 Suppl 1:4570–4577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000072107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Bjorkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. 2011. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voss JD, Leon JC, Dhurandhar NV, Robb FT. 2015. Pawnobiome: manipulation of the hologenome within one host generation and beyond. Front Microbiol 6:697. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan L, Liu M, Simister R, Webster NS, Thomas T. 2013. Marine microbial symbiosis heats up: the phylogenetic and functional response of a sponge holobiont to thermal stress. ISME J 7:991–1002. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seedorf H, Griffin NW, Ridaura VK, Reyes A, Cheng J, Rey FE, Smith MI, Simon GM, Scheffrahn RH, Woebken D, Spormann AM, Van Treuren W, Ursell LK, Pirrung M, Robbins-Pianka A, Cantarel BL, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Knight R, Gordon JI. 2014. Bacteria from diverse habitats colonize and compete in the mouse gut. Cell 159:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell JH, Foster CM, Vishnivetskaya T, Campbell AG, Yang ZK, Wymore A, Palumbo AV, Chesler EJ, Podar M. 2012. Host genetic and environmental effects on mouse intestinal microbiota. ISME J 6:2033–2044. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spor A, Koren O, Ley R. 2011. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:279–290. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meisel JD, Kim DH. 2014. Behavioral avoidance of pathogenic bacteria by Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Immunol 35:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rook GA. 2013. Regulation of the immune system by biodiversity from the natural environment: an ecosystem service essential to health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:18360–18367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313731110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ezenwa VO, Gerardo NM, Inouye DW, Medina M, Xavier JB. 2012. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science 338:198–199. doi: 10.1126/science.1227412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sison-Mangus MP, Mushegian AA, Ebert D. 2015. Water fleas require microbiota for survival, growth and reproduction. ISME J 9:59–67. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullam KE, Pichon S, Schaer TMM, Ebert D. 2017. The combined effect of temperature and host clonal line on the microbiota of a planktonic crustacean. Microb Ecol 76:506–517. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macke E, Callens M, De Meester L, Decaestecker E. 2017. Host-genotype dependent gut microbiota drives zooplankton tolerance to toxic cyanobacteria. Nat Commun 8:1608. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01714-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton P, Rowan M, Webster K, Peters R. 1979. Browsing and grazing by cladoceran filter feeders. Can J Zool 57:206–212. doi: 10.1139/z79-019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Ebert D. 2002. In deep trouble: habitat selection constrained by multiple enemies in zooplankton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:5481–5485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082543099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbore R, Andras JP, Routtu J, Ebert D. 2016. Ecological genetics of sediment browsing behaviour in a planktonic crustacean. J Evol Biol 29:1999–2009. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster ZSL, Sharpton T, Grunwald NJ. 2017. Metacoder: an R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peerakietkhajorn S, Kato Y, Kasalický V, Matsuura T, Watanabe H. 2016. Betaproteobacteria Limnohabitans strains increase fecundity in the crustacean Daphnia magna: symbiotic relationship between major bacterioplankton and zooplankton in freshwater ecosystem. Environ Microbiol 18:2366–2374. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi W, Nong G, Preston JF, Ben-Ami F, Ebert D. 2009. Comparative metagenomics of Daphnia symbionts. BMC Genomics 10:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callens M, Macke E, Muylaert K, Bossier P, Lievens B, Waud M, Decaestecker E. 2016. Food availability affects the strength of mutualistic host-microbiota interactions in Daphnia magna. ISME J 10:911–920. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckert EM, Pernthaler J. 2014. Bacterial epibionts of Daphnia: a potential route for the transfer of dissolved organic carbon in freshwater food webs. ISME J 8:1808–1819. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaltenpoth M, Engl T. 2014. Defensive microbial symbionts in Hymenoptera. Funct Ecol 28:315–327. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, Glickman JN, Siebert R, Baron RM, Kasper DL, Blumberg RS. 2012. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science 336:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum JE, Fischer CN, Miles J, Handelsman J. 2013. Frequent replenishment sustains the beneficial microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster. mBio 4:e00860-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00860-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossart H-P, Dziallas C, Leunert F, Tang KW. 2010. Bacteria dispersal by hitchhiking on zooplankton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:11959–11964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kluttgen B, Dulmer U, Engels M, Ratte HT. 1994. ADaM, an artificial freshwater for the culture of zooplankton. Water Res 28:743–746. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(94)90157-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. 2010. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 85:935–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edgar RC. 2013. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, Calus ST, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF, Turner P, Parkhill J, Loman NJ, Walker AW. 2014. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol 12:87. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0087-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive of the EBI under accession number PRJEB30308. Data tables, OTU sequences, and code used for analysis can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/amusheg/Daphnia-microbiota-behavior and in Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.g75r459.