While influenza A viruses of subtype H2N2 were at the origin of the Asian influenza pandemic, little is known about the antigenic changes that occurred during the twelve years of circulation in humans, the role of preexisting immunity, and the evolutionary rates of the virus. In this study, the antigenic map derived from hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers of cell-cultured virus isolates and ferret postinfection sera displayed a directional evolution of viruses away from earlier isolates. Furthermore, individual mutations in close proximity to the receptor-binding site of the HA molecule determined the antigenic reactivity, confirming that individual amino acid substitutions in A/H2N2 viruses can confer major antigenic changes. This study adds to our understanding of virus evolution with respect to antigenic variability, rates of virus evolution, and potential escape mutants of A/H2N2.

KEYWORDS: antigenic evolution, influenza virus A/H2N2, molecular drift, pandemic

ABSTRACT

Influenza A/H2N2 viruses caused a pandemic in 1957 and continued to circulate in humans until 1968. The antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 viruses over time and the amino acid substitutions responsible for this antigenic evolution are not known. Here, the antigenic diversity of a representative set of human A/H2N2 viruses isolated between 1957 and 1968 was characterized. The antigenic change of influenza A/H2N2 viruses during the 12 years that this virus circulated was modest. Two amino acid substitutions, T128D and N139K, located in the head domain of the H2 hemagglutinin (HA) molecule, were identified as important determinants of antigenic change during A/H2N2 virus evolution. The rate of A/H2N2 virus antigenic evolution during the 12-year period after introduction in humans was half that of A/H3N2 viruses, despite similar rates of genetic change.

IMPORTANCE While influenza A viruses of subtype H2N2 were at the origin of the Asian influenza pandemic, little is known about the antigenic changes that occurred during the twelve years of circulation in humans, the role of preexisting immunity, and the evolutionary rates of the virus. In this study, the antigenic map derived from hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers of cell-cultured virus isolates and ferret postinfection sera displayed a directional evolution of viruses away from earlier isolates. Furthermore, individual mutations in close proximity to the receptor-binding site of the HA molecule determined the antigenic reactivity, confirming that individual amino acid substitutions in A/H2N2 viruses can confer major antigenic changes. This study adds to our understanding of virus evolution with respect to antigenic variability, rates of virus evolution, and potential escape mutants of A/H2N2.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A viruses of the H2N2 subtype initiated a pandemic in 1957, causing morbidity and mortality in humans, an event also known as the “Asian flu pandemic” (1–3). No surveillance systems were in place in 1957 to accurately detect and record the A/H2N2 pandemic outbreak scenario. Based on death certificates and newspaper articles, excess mortality was found to occur in waves, with the highest number of events between October 1957 and March 1958 in 5- to 14-year-olds (4). The A/H2N2 virus originated upon reassortment between a previously circulating seasonal human A/H1N1 virus and an avian A/H2N2 virus. The latter virus contributed the HA, neuraminidase (NA), and polymerase basic protein 1 (PB1) gene segments to the pandemic A/H2N2 virus (5–7). This virus circulated in the human population until it was replaced by an A/H3N2 influenza virus in 1968. Today, more than 50 years after the last detected A/H2N2 virus infection in humans, immunity against A/H2N2 viruses is waning. The threat of reintroduction and spread of H2 viruses in humans remains, because A/H2N2 viruses and other influenza A viruses with combinations of H2 and various NA genes continuously circulate in avian species and incidentally in swine (8–10). Several vaccine candidates have been developed for pandemic preparedness (11–13), and prophylactic vaccination of individuals at increased risk has been proposed (14).

The HA glycoprotein of influenza A viruses is the major target for neutralizing antibodies and continuously undergoes antigenic evolution by acquiring substitutions to escape antibody-mediated immunity (15). Five antigenic sites in the HA molecule have been identified to determine antigenic properties of seasonal human influenza viruses (16–18). In the case of A/H2N2 influenza viruses, six antigenic sites (I-A to I-D, II-A, and II-B) in the HA have been recognized to play a major role in antigenic change (19). These sites structurally correspond to the five sites described for A/H3N2 influenza viruses (designated A to E). Site II-A is unique for A/H2N2 influenza viruses, highly conserved, and located in the HA stem domain.

After seminal studies that described the structural importance of the HA receptor-binding site (RBS) for antigenic variation (17, 20, 21), it was shown recently that a mere seven amino acid positions on HA located immediately adjacent to the receptor binding site (RBS) largely determined antigenic changes that occurred during A/H3N2 influenza virus circulation in humans from 1968 to 2003 (22). Similarly, a study on clade 2.1 A/H5N1 viruses showed that substitutions in close proximity to the RBS dictated antigenic change of avian A/H5N1 influenza viruses emerging in poultry (23), and amino acid changes close to the RBS were found to induce antigenic change in A/H1N1pdm09 viruses (24–26). Substitutions in the head domain of the HA molecule have also been demonstrated to determine the antigenic phenotype of equine and swine influenza A viruses (27, 28). Combined, these studies demonstrate the importance of RBS-proximal substitutions for antigenic drift of influenza A viruses.

In this study, the antigenic properties of a representative set of human A/H2N2 virus isolates spanning the period from 1957 to 1968 were assessed with respect to their reactivity to ferret postinfection sera in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays. The substitutions responsible for major antigenic differences between A/H2N2 influenza viruses were mapped by site-directed mutagenesis and generation of recombinant viruses.

RESULTS

Genetic and antigenic diversity of A/H2N2 viruses.

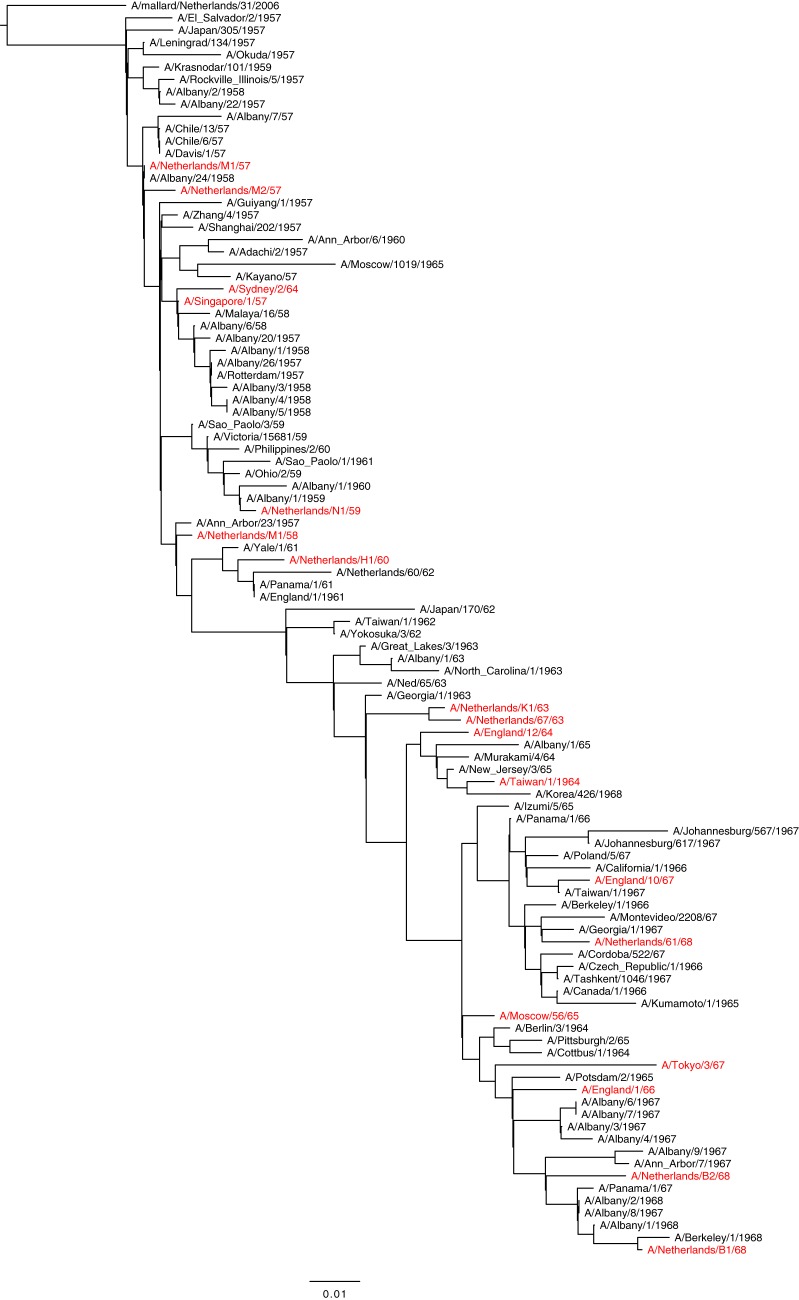

The genetic variation of human A/H2N2 influenza viruses isolated between 1957 and 1968 was assessed by maximum likelihood algorithms in an HA1 amino acid phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). The tree displays a ladder-like structure that indicates gradual accumulation of mutations over time. A set of 18 human A/H2N2 influenza virus isolates representative of genetic variation over the 12-year period and that was available in our laboratory was compiled (highlighted in red in Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on HA1 amino acid sequences of human A/H2N2 viruses. Virus isolates used for antigenic characterization are highlighted in red.

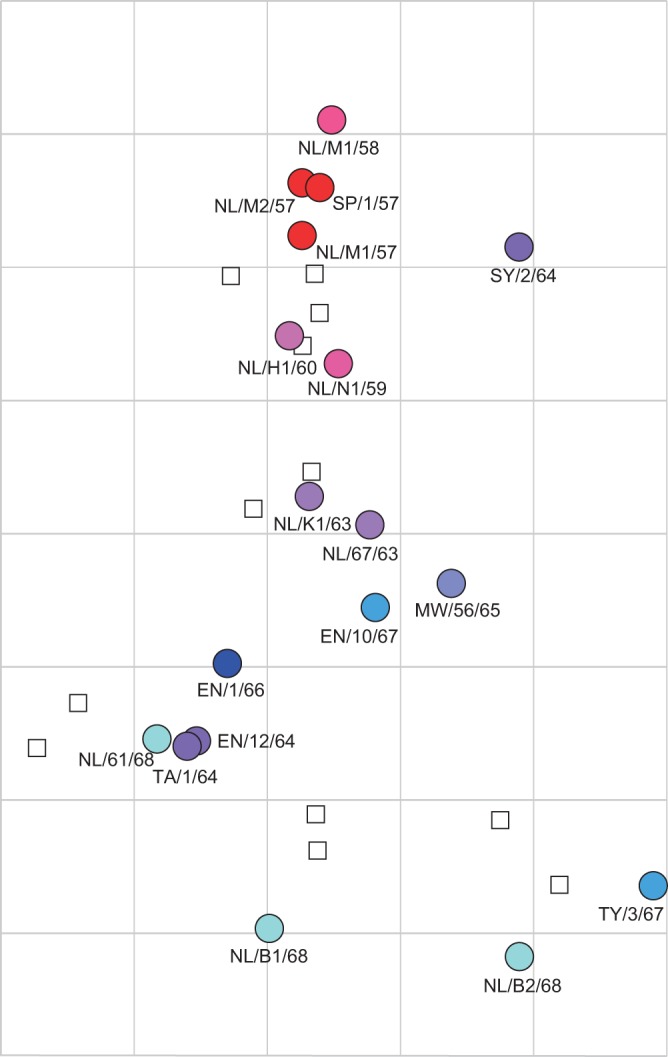

HI titers of the set of 18 A/H2N2 viruses and 6 A/H2N2 ferret postinfection sera revealed a typical pattern of influenza virus antigenic drift, with high antibody titers of antisera against homologous and contemporary viruses and lower titers against noncontemporary strains (Table 1). HI titers were processed using antigenic cartography methods to yield an antigenic map (Fig. 2), revealing directional antigenic progression of later isolates away from early strains over time. Viruses isolated in the same or subsequent years generally grouped together in the map and thus were antigenically similar. Exceptions were A/Sydney/2/64 and the latest A/H2N2 viruses. In this study, the maximum antigenic distance between any pair of wild-type viruses was 6.4 antigenic units (AU) between A/Netherlands/M1/1958 (NL/M1/58) and A/Netherlands/B2/1968 (NL/B2/68). Viruses isolated in 1964 were antigenically highly diverse; whereas A/England/12/1964 (EN/12/64) and A/Taiwan1/64 (TW/1/64) drifted 3.9 antigenic units away from NL/M1/57, A/Sydney/2/1964 (SY/2/64) was only 1.6 antigenic units away from NL/M1/57. The three viruses isolated shortly before the introduction of the first A/H3N2 virus in 1968 (NL/61/68, NL/B1/68, and NL/B2/68) were particularly divergent in the antigenic map, with 3.2 antigenic units of difference between NL/61/68 and NL/B2/68.

TABLE 1.

Hemagglutination inhibition titers for wild-type viruses toward A/H2N2 postinfection ferret antiseraa

| Virus isolate | Titer toward ferret postinfection antiserum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP/305/57 | SP/1/57 | NL/K1/63 | EN/1/66 | TY/3/67 | NL/B1/68 | |

| A/NETHERLANDS/M1/57 [NL/M1/57] | 2,560 | 1,600 | 1,280 | 320 | 40 | 160 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/M2/57 [NL/M2/57] | 960 | 1,600 | 960 | 240 | 40 | 80 |

| A/SINGAPORE/1/57 [SP/1/57] | 1,600 | 1,920 | 1,280 | 160 | 35 | 60 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/M1/58 [NL/M1/58] | 960 | 960 | 960 | 160 | 30 | 60 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/N1/59 [NL/N1/59] | 1,920 | 1,920 | 1,920 | 800 | 240 | 240 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/H1/60 [NL/H1/60] | 1,920 | 1,600 | 2,560 | 480 | 120 | 200 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/67/63 [NL/67/63] | 560 | 1,280 | 4,480 | 560 | 240 | 800 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/K1/63 [NL/K1/63] | 1,600 | 1,120 | 5,760 | 960 | 200 | 800 |

| A/ENGLAND/12/64 [EN/12/64] | 60 | 240 | 2,240 | 2,880 | 320 | 1,120 |

| A/SYDNEY/2/64 [SY/2/64] | 480 | 800 | 480 | 200 | 60 | 160 |

| A/TAIWAN/1/64 [TA/1/64] | 80 | 320 | 1,120 | 1,920 | 320 | 1,120 |

| A/MOSCOW/56/65 [MW/56/65] | 560 | 240 | 2,560 | 480 | 240 | 1,280 |

| A/ENGLAND/1/66 [EN/1/66] | 640 | 320 | 3,840 | 6,400 | 320 | 2,240 |

| A/ENGLAND/10/67 [EN/10/67] | 1,120 | 320 | 2,560 | 800 | 240 | 1,120 |

| A/TOKYO/3/67 [TY/3/63] | 80 | 80 | 160 | 320 | 960 | 320 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/61/68 [NL/61/68] | 320 | 160 | 1,120 | 2,240 | 160 | 800 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/B1/68 [NL/B1/68] | 20 | 80 | 960 | 960 | 320 | 2 ,880 |

| A/NETHERLANDS/B2/68 [NL/B2/68] | 50 | 60 | 320 | 640 | 640 | 640 |

One serum per isolate was selected to represent the two individual ferret sera since variation in HI titers between repeat sera was negligible. Viruses emphasized in Fig. 3 are in bold and homologous HI titers are underlined.

FIG 2.

Antigenic map of human A/H2N2 influenza viruses as measured in HI assays with ferret postinfection antisera. Circles indicate the position of viruses, squares represent two ferret antisera raised against each of the viruses A/Japan/305/57, A/Singapore/1/57, A/Netherlands/K1/63, A/England/1/66, A/Tokyo/3/67, and A/Netherlands/B1/68. The underlying grid depicts the scale of antigenic difference between the viruses, with each square representing one antigenic unit or a 2-fold difference in HI titer. Years of isolation of the A/H2N2 virus isolates are indicated, ranging from 1957 (red) to 1968 (blue).

Molecular basis of antigenic change in A/H2N2 viruses.

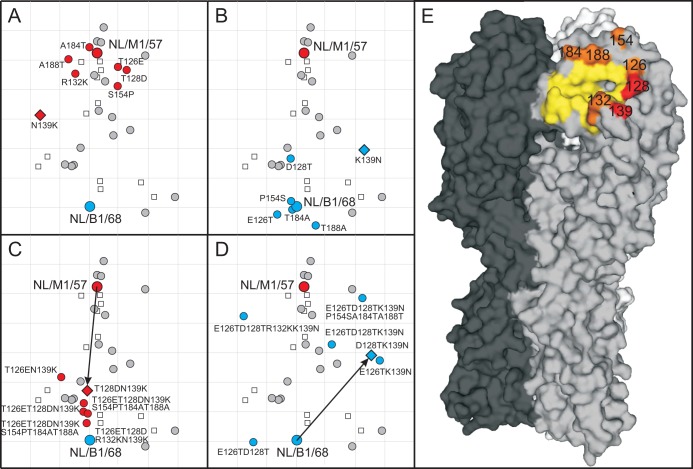

The head domain of the HA molecule is the main target of neutralizing antibodies (17, 29). Previous studies indicated that amino acid substitutions near the RBS and exposed on the surface of the HA molecule were responsible for major antigenic drift of influenza A/H3N2, A/H5N1 viruses, and influenza B virus (23, 25, 30). Amino acid changes on positions 100 to 250 were compared as a coarse outline of the globular head domain, including the RBS area of the H2 HA. A set of 7 amino acid substitutions (T126E, T128D, R132K, N139K, S154P, A184T, and A188T) was consistently found in later A/H2N2 virus isolates compared to the earlier strains and hence could explain the antigenic differences between early and late strains. Throughout this study, amino acid positions are numbered as suggested by Burke and Smith (31). Single amino acid substitutions and combinations thereof were introduced and tested in recombinant viruses harboring the HA gene of NL/M1/57 or NL/B1/68 in a backbone of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (A/H1N1). All reverse genetics viruses were rescued, with the exception of NL/B1/68 HA K132R mutant virus, which was not rescued despite three independent rescue attempts.

A substitution at position 139 was responsible for a substantial antigenic change of 2.9 antigenic units (AU) when tested in viruses containing HA genes of NL/M1/57 and NL/B1/68 (Fig. 3A and B, Table 2). This position is surface exposed and located on a protruding loop adjacent to the RBS (Fig. 3E). All other individual mutations in NL/M1/57 and NL/B1/68 had an antigenic effect of less than 1.7 AU compared to the wild-type virus. The effect of N139K in NL/M1/57 increased with the addition of T128D to a 3.6-AU distance from the NL/M1/57 virus carrying the NL/M1/57 wild-type HA (Fig. 3C). When the combination of K139N and D128T was tested in NL/B1/68 HA, only a rather small difference in antigenic effect (1.1 AU) was measured compared to K139N alone (Fig. 3D). Here, a combination of six amino acid substitutions (E126T, D128T, K139N, S154P, A184T, and A188T) was necessary in order for the virus to be antigenically similar to NL/M1/57 and located 5.4 antigenic units from NL/B1/68. Each substitution in addition to K139N had a rather small but incremental effect on the antigenic reactivity of the H2N2 HA.

FIG 3.

Summary of substitutions responsible for antigenic differences between NL/M1/57 and NL/B1/68. Antigenic maps showing the antigenic change caused by individual amino acid substitutions introduced into NL/M1/57 (A) or NL/B1/68 (B) and combinations of mutations introduced into NL/M1/57 (C) or NL/B1/68 (D). Viruses are shown as circles of different colors, with a diamond indicating the mutant virus with the largest antigenic distance to the corresponding wild-type strain. Sera are indicated as open squares. The underlying map of wild-type viruses from Fig. 2 is shown in gray, and its positioning is kept constant. The arrows indicate the antigenic distance of a double mutant that spans a long distance between the earliest and latest isolates of A/H2N2. Structure of an HA trimer (E) with individual monomers in shades of gray, the RBS in yellow, and mutations near the RBS with a measurable effect on antigenicity in orange. The two mutations with the biggest combined effect in panel C are colored in red (T128D and N139K).

TABLE 2.

Hemagglutination inhibition titers for mutant viruses toward A/H2N2 postinfection ferret antiseraa

| Virus isolate | Titer toward ferret postinfection antiserum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP/305/57 | SP/1/57 | NL/K1/63 | EN/1/66 | TY/3/67 | NL/B1/68 | |

| NL/M1/57_T126E | 1,600 | 1,440 | 640 | 320 | 80 | 560 |

| NL/M1/57_T128D | 1,600 | 960 | 640 | 280 | 80 | 640 |

| NL/M1/57_R132K | 2,240 | 1,280 | 640 | 800 | 80 | 320 |

| NL/M1/57_N139K | 160 | 1,120 | 640 | 1,920 | 80 | 640 |

| NL/M1/57_S154P | 1,920 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 560 | 360 | 280 |

| NL/M1/57_T184A | 1,600 | 1,920 | 1,120 | 320 | 20 | 160 |

| NL/M1/57_T188A | 1,280 | 1,600 | 1,920 | 480 | 20 | 160 |

| NL/B1/68_E126T | 40 | 80 | 640 | 960 | 160 | 1,280 |

| NL/B1/68_D128T | 1,120 | 240 | 1,440 | 2,240 | 160 | 2,240 |

| NL/B1/68_K139N | 400 | 160 | 640 | 320 | 320 | 2,240 |

| NL/B1/68_P154S | 20 | 160 | 640 | 800 | 320 | 3,200 |

| NL/B1/68_A184T | 40 | 120 | 480 | 640 | 160 | 2,560 |

| NL/B1/68_A188T | 20 | 100 | 160 | 320 | 240 | 1,920 |

| NL/M1/57_T126EN139K | 560 | 640 | 640 | 1,920 | 160 | 1,920 |

| NL/M1/57_T128DN139K | 80 | 640 | 640 | 1,120 | 160 | 2,240 |

| NL/M1/57_T126ET128DN139K | 100 | 640 | 320 | 800 | 140 | 2,880 |

| NL/M1/57_T126ET128DR132KN139K | 160 | 560 | 280 | 800 | 160 | 1,920 |

| NL/M1/57_T126ET128DN139KS154PT184AT188A | 80 | 320 | 960 | 800 | 160 | 3,200 |

| NL/M1/57_T126ET128DR132KN139KS154PT184AT188A | 80 | 320 | 640 | 800 | 160 | 2,560 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TK139N | 160 | 320 | 480 | 320 | 160 | 640 |

| NL/B1/68_D128TK139N | 320 | 480 | 1,280 | 320 | 160 | 640 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TD128T | 80 | 80 | 960 | 640 | 80 | 640 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TD128TK139N | 960 | 480 | 2,240 | 640 | 160 | 640 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TD128TK139NK132R | 640 | 400 | 2,240 | 320 | 60 | 320 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TD128TK139NP154SA184TA188T | 960 | 560 | 480 | 280 | 160 | 100 |

| NL/B1/68_E126TD128TR132KK139NP154SA184TA188T | 640 | 480 | 640 | 60 | 50 | 40 |

Viruses emphasized in Fig. 3 are in bold.

Evolutionary rates of A/H2N2 and A/H3N2.

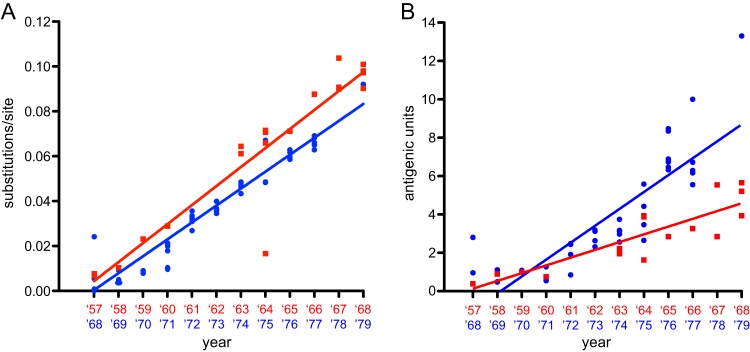

Next, the genetic and antigenic change over time after introduction of the new influenza virus subtype in the human population was investigated (Fig. 4). The rate of evolution of A/H2N2 HA1 was estimated and compared to the rate of HA1 evolution during the first 12 years of A/H3N2 circulation after its introduction in the human population in 1968, based on phylogenetic trees generated here and by Smith et al. (15). The average rate of genetic evolution (nucleotide substitutions per site per year) estimated in this analysis was 8.47 × 10−3 for H2N2 and 7.53 × 10−3 for H3N2 (Fig. 4A). The average rate of antigenic evolution for A/H2N2 from 1957 to 1968 was 0.4 AUs per year, calculated from the slope of the best-fit regression line of the distances in the antigenic map (Fig. 4B). Using the A/H3N2 data set reported by Smith et al. (15), the maximum distance in the antigenic map during the first 12 years of circulation (1968 to 1979) was 13.3 AUs between isolates A/Bilthoven/16190/1968 and A/Bangkok/1/1979, resulting in an average evolutionary rate of 0.9 AUs per year, somewhat lower than the rate reported over the 35-year period from 1968 to 2003 of 1.2 AUs per year (15). Thus, the antigenic evolution of the A/H2N2 virus was approximately two times slower than antigenic evolution of A/H3N2 during the first 12 years of circulation and three times slower than that over the 35-year period.

FIG 4.

Rates of genetic and antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 and A/H3N2 virus during 12 years of circulation in humans. Genetic (A) and antigenic (B) distances of the A/H2N2 (red squares) and A/H3N2 (blue circles) viruses from the first human virus isolates in 1957 (A/Netherlands/M1/1957) and 1968 (A/Bilthoven/16190/1968). Rates are derived from the slope of the best-fit regression line.

To investigate if these differences in antigenic evolution were potentially due to increased evolutionary pressures to select antigenic escape mutants or were the consequence of an overall increased rate of nucleotide substitution in HA1, the nucleotide substitution rates were estimated using Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Trees (BEAST) version 1.8.1 with a relaxed log-normal clock and the Bayesian skyride time-aware model. All available sequences in public databases were downloaded, which resulted after curation in alignments of 98 sequences for A/H2N2 virus HA1 and 103 sequences for H3N2 virus HA1. The mean rate of nucleotide substitution for A/H2N2 HA1 was determined to be 4.88 × 10−3 nucleotide substitutions per site per year (highest posterior density [HPD], 3.68 × 10−3 to 6.21 × 10−3). The nucleotide substitution rate of A/H3N2 virus HA1 was determined to be 4.48 × 10−3 (HPD, 3.57 × 10−3 to 5.49 × 10−3), comparable to previous results obtained for A/H3N2 HA1 at 5.15 × 10−3 (HPD, 4.62 × 10−3 to 5.70 × 10−3) (29). This rate of A/H3N2 virus evolution was not statistically significantly different from the A/H2N2 virus rate (Bayes factors: H2 > H3, 1.533; H3 > H2, 0.651).

DISCUSSION

Using a unique and comprehensive collection of human A/H2N2 viruses with low passage history and matching ferret postinfection sera spanning the time of circulation of A/H2N2 viruses in humans, the antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 viruses over time was analyzed. Phylogenetic analysis of HA sequences of human A/H2N2 viruses resulted in the ladder-like structure of the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) due to the gradual accumulation of mutations characteristic for human influenza A viruses (32, 33). All H2N2 virus isolates available at our institute were amplified by PCR and sequenced. They were confirmed to be representative of the major genetic diversity and were tested in HI assays for their reactivity to corresponding ferret antisera and to construct antigenic maps. The antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 viruses did not demonstrate obvious clustering of virus isolates in contrast to A/H3N2 viruses (22) but a rather gradual pattern of antigenic change over time. However, the number of strains included in the current analysis and the short time span of A/H2N2 virus circulation may simply be insufficient for clustering to be obvious.

A single amino acid change from asparagine (N) to lysine (K) at position 139 in the HA molecule played a prominent role in determining the antigenic properties of A/H2N2 viruses. When introduced in either NL/M1/57 or NL/B1/68, this substitution had an antigenic effect of 2.9 antigenic units, describing roughly half of the observed antigenic diversity of A/H2N2 HA. No other single amino acid substitution was responsible for a greater antigenic effect than D128T in the context of NL/B1/68 (Fig. 3C and D). Both positions 128 and 139 are located close to the RBS in the HA protein, similarly to the substitutions that were previously shown to be important for major antigenic change of other influenza A viruses and influenza B virus (22, 23, 25). Additional individual substitutions at positions 126, 132, 154, 184, and 188 had only minor antigenic effects, but collectively with positions 139 and 128 explained the major antigenic changes observed in A/H2N2 viruses. Also, these changes were located in close proximity to the RBS (Fig. 3). For the antigenic evolution of A/H3N2 virus, major antigenic change was caused by substitutions at only seven positions around the RBS, with relatively small effects of additional substitutions. For A/H2N2 virus, a single amino acid substitution also determined the antigenic phenotype of subsequent major drift variants, but the effect of additional substitutions was more substantial, potentially due to the different time scales at which the antigenic evolution was measured and the lack of clustering of strains in the A/H2N2 map.

Whereas A/H1N1pdm09 viruses remained remarkably antigenically stable since their introduction in humans (34, 35), A/H3N2 viruses displayed a more rapid accumulation of substitutions with major impact on antigenic evolution over time, possibly implying differential abilities of various HA subtypes to accommodate substitutions that affect antigenic properties (25, 36). The antigenic evolution of influenza B virus was also found to be relatively slow compared to that of A/H3N2 virus (22, 30). Here, the antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 was found to be two times slower than the antigenic evolution of A/H3N2 virus during its first twelve years of circulation, and three times slower than that during the period of A/H3N2 virus circulation from 1968 to 2003, while their respective nucleotide substitution rates differed only slightly in the first 12 years of virus circulation in humans. Although the exact factors contributing to this difference in rates of antigenic evolution are not known, antibody-mediated selection of escape mutants likely played an important role. Human sera obtained before 1957 from the elderly contained antibodies that react to A/H2N2 virus, suggesting that the pandemic of 1889 to 1890 was also caused by an influenza A virus of the H2 subtype (37). However, this preexisting immunity in the population apparently did not result in increased antibody-mediated selection for A/H2N2 virus variants, similar to the lack of rapid natural selection of escape mutants for A/H1N1pdm09 virus.

Combined, the genetic variability of A/H2N2 was comparable to that of other influenza A subtypes, whereas the antigenic evolution was relatively slow, indicating that population immunity to A/H2N2 did not facilitate rapid antigenic evolution at the time of virus introduction. The genetic data indicate that the size of the susceptible population, as well as virus turnover, was likely similar to that of other influenza virus subtypes. We hypothesize that a combination of factors, including the intrinsic capacity of the influenza virus HA to accumulate mutations responsible for antigenic evolution, preexisting immunity at the time of introduction, susceptible population size, and prior circulation of a certain subtype leading to human adaptation, have a combined effect on antigenic evolution of the HA.

This study describes directional antigenic evolution of A/H2N2 viruses during circulation in humans and highlights the importance of amino acid sites in close proximity to the RBS for antigenic reactivity of A/H2N2 HA. Rates of antigenic evolution in A/H2N2 viruses were lower than those in A/H3N2 viruses, possibly implying differences in the structural freedom of the HA molecules to evolve.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biosafety considerations.

All experiments involving A/H2N2 viruses were conducted under biosafety level 3 (BSL3) conditions. Reassortant viruses in the backbone of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) harboring the HA gene of A/H2N2 viruses were used under BSL2 conditions.

Ferret antisera.

Ferret postinfection antisera were prepared against virus isolates A/Japan/305/1957 (JP/305/57), A/Singapore/1/1957 (SP/1/57), A/Netherlands/K1/1963 (NL/K1/63), A/England/1/66 (EN/1/66), A/Tokyo/3/67 (TY/3/67), and A/Netherlands/B1/1968 (NL/B1/68). To this end, male ferrets (Mustela putorios furo) were obtained from an accredited ferret breeder. All animals tested negative prior to the start of the experiments for antibodies against H1, H2, and H3 influenza A viruses, influenza B virus, and Aleutian disease virus. Ferret antisera were prepared by intranasal inoculation of the animals with the respective viruses, and antisera were collected 14 days after inoculation. Ferret housing and animal experiments were conducted in strict compliance with European guidelines (EU directive on animal testing 86/609/EEC) and Dutch legislation (Experiments on Animal Act, 1997). The experimental protocol was approved by an independent animal experimentation ethical review committee (“Stichting Dier Experimenten Commissie Consult”). Animal welfare was monitored daily, and all animal handling was performed under sedation to minimize discomfort.

Viruses and cells.

The following 18 A/H2N2 viruses were used in this study (GenBank accession numbers for HA genes in parentheses): A/Netherlands/M1/57 (KM402801), A/Netherlands/M2/57 (KM885170), A/Singapore/1/57 (CY125894), A/Netherlands/M1/58 (CY077741), A/Netherlands/N1/59 (CY077904), A/Netherlands/H1/60 (CY077786), A/Netherlands/67/63 (CY125886), A/Netherlands/K1/1963 (CY077733), A/England/12/64 (AY209967), A/Sydney/2/64 (KP412320), A/Taiwan/1/1964 (DQ508881), A/Moscow/56/65 (CY031603), A/England/1/66 (KP412318), A/England/10/67 (AY209980), A/Tokyo/3/67 (AY209987), A/Netherlands/61/68 (KP412319), A/Netherlands/B1/68 (KM402809), and A/Netherlands/B2/68 (KM885174). Human A/H2N2 virus samples from the Netherlands were collected from individuals with influenza-like symptoms during the years 1957 to 1968. From these samples, virus isolates were obtained by culture in tertiary monkey kidney cells (tMK) and Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK) for a maximum of five passages, without prior inoculation in embryonated chicken eggs. Complete HA genes of viruses A/Netherlands/M1/1957 and A/Netherlands/B2/1968 were amplified from low-passage viruses and cloned in a modified pHW2000 expression plasmid as described previously (38). Recombinant viruses consisting of the HA gene of A/H2N2 and the 7 remaining gene segments of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (A/H1N1) were generated by reverse genetics (39). Introduction of mutations in the HA gene was performed using the QuikChange multisite directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The presence or absence of mutations was confirmed by sequence analysis of the HA gene. Virus stocks were generated by inoculation of MDCK cells with 293T transfection supernatant. The inoculum was removed after 2 h and replaced by MDCK infection medium, consisting of Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 1.5 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate, 10 mM HEPES, nonessential amino acids, and 25 μg/ml N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin. Subsequently, cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2, and virus-containing supernatant was harvested 3 days after inoculation.

293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Lonza Benelux, Breda, the Netherlands) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and nonessential amino acids (MP Biomedicals). MDCK cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM; Lonza) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 1.5 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate (Lonza), 10 mM HEPES (Lonza), and nonessential amino acids (MP Biomedicals).

Hemagglutination inhibition assays.

HI assays using a panel of postinfection ferret antisera were performed as described previously (15). Briefly, ferret antisera were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase) and incubated at 37°C overnight, followed by inactivation of the enzyme at 56°C for one hour. Twofold serial dilutions of the antisera, starting at a 1:20 dilution, were mixed with 25 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing four hemagglutinating units of virus and were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, 25 μl 1% turkey erythrocytes were added, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for one hour. HI titers were read and expressed as the reciprocal value of the highest dilution of the serum that completely inhibited agglutination of virus and erythrocytes.

Computational analyses.

Amino acid sequences of human A/H2N2 HA1 were aligned and analyzed by maximum likelihood phylogeny using PhyML 3.0 software (40). The sequence of avian A/H2N2 isolate A/mallard/Netherlands/31/2006 (GenBank accession number ACR58563) was used as an outgroup.

Antigenic maps were constructed as described previously (15). Antigenic cartography is a method for the quantitative analysis and visualization of HI data. In an antigenic map, the distance between antiserum point S and antigen point A corresponds to the difference between the log2 of the maximum titer observed for antiserum S against any antigen and the log2 of the titer for antiserum S against antigen A. Each titer in an HI table can be thought of as specifying a target distance for the points in an antigenic map. Modified multidimensional scaling methods are used to arrange the antigen and antiserum points in the antigenic map to best satisfy the target distances as specified by the HI data. The result is a map in which the distance between the points represents antigenic distance as measured by the HI assay, in which the distances between antigens and antisera are inversely related to the log2 HI titer. Since antisera are tested against multiple antigens, and antigens are tested against multiple antisera, many measurements can be used to determine the position of the antigen and antiserum in an antigenic map, thus improving the resolution of interpretation for HI data.

The amino acid positions responsible for major changes in HI patterns were plotted on the surface of the crystal structure of A/Singapore/1/1957 HA (PDB accession number 2WR7) (41) using MacPyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System version 1.3; Schrödinger, LLC).

Overall rates of evolutionary change (nucleotide substitutions per site per year) were estimated using the BEAST program version 1.8.1 (42), the uncorrelated log-normal relaxed molecular clock, and the HKY85 substitution model (43). This analysis was conducted with a time-aware linear Bayesian skyride coalescent tree prior (44) over the unknown tree space, with relatively uninformative priors on all model parameters using the GTR+G+I model with no codon positions enforced. Two independent Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses for HA1 for 50 million states, sampling every 5,000 states, were performed. Convergences and effective sample sizes of the estimates were checked using Tracer version 1.5 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/), and the first 10 % of each chain was discarded as burn-in. Uncertainty in parameter estimates is reported as values of the 95 % highest posterior density (HPD).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Udayan Joseph for help with the BEAST program package. D.F.B. and D.J.S. acknowledge the use of the CamGrid distributed computing resource.

This work was financed through NIAID-NIH contracts HHSN226200700010C and HHSN272201400008C. D.F.B. and D.J.S. were additionally supported in part by NIH Director’s Pioneer Award DP1-OD000490-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenfeld HL, Kilbourne ED, Louria DB, Rogers DE. 1959. Studies on influenza in the pandemic of 1957–1958. I. An epidemiologic, clinical and serologic investigation of an intrahospital epidemic, with a note on vaccination efficacy. J Clin Invest 38:199–212. doi: 10.1172/JCI103789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilbourne ED. 2006. Influenza pandemics of the 20th century. Emerg Infect Dis 12:9–14. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viboud C, Simonsen L, Fuentes R, Flores J, Miller MA, Chowell G. 2016. Global mortality impact of the 1957–1959 influenza pandemic. J Infect Dis 213:738–745. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobos AJ, Nelson CG, Jehn M, Viboud C, Chowell G. 2016. Mortality and transmissibility patterns of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Maricopa County, Arizona. BMC Infect Dis 16:405. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1716-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindstrom SE, Cox NJ, Klimov A. 2004. Genetic analysis of human H2N2 and early H3N2 influenza viruses, 1957–1972: evidence for genetic divergence and multiple reassortment events. Virology 328:101–119. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schafer JR, Kawaoka Y, Bean WJ, Suss J, Senne D, Webster RG. 1993. Origin of the pandemic 1957 H2 influenza A virus and the persistence of its possible progenitors in the avian reservoir. Virology 194:781–788. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholtissek C, Rohde W, Von Hoyningen V, Rott R. 1978. On the origin of the human influenza virus subtypes H2N2 and H3N2. Virology 87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma W, Vincent AL, Gramer MR, Brockwell CB, Lager KM, Janke BH, Gauger PC, Patnayak DP, Webby RJ, Richt JA. 2007. Identification of H2N3 influenza A viruses from swine in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20949–20954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munster VJ, Baas C, Lexmond P, Waldenstrom J, Wallensten A, Fransson T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Beyer WE, Schutten M, Olsen B, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2007. Spatial, temporal, and species variation in prevalence of influenza A viruses in wild migratory birds. PLoS Pathog 3:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu H, Peng X, Peng X, Cheng L, Wu N. 2016. Genetic and molecular characterization of a novel reassortant H2N8 subtype avian influenza virus isolated from a domestic duck in Zhejiang Province in China. Virus Genes 52:863–866. doi: 10.1007/s11262-016-1368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2010. Safety, immunogencity, and efficacy of a cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (H2N2) vaccine in mice and ferrets. Virology 398:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hehme N, Engelmann H, Kunzel W, Neumeier E, Sanger R. 2002. Pandemic preparedness: lessons learnt from H2N2 and H9N2 candidate vaccines. Med Microbiol Immunol 191:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s00430-002-0147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isakova-Sivak I, de Jonge J, Smolonogina T, Rekstin A, van Amerongen G, van Dijken H, Mouthaan J, Roholl P, Kuznetsova V, Doroshenko E, Tsvetnitsky V, Rudenko L. 2014. Development and pre-clinical evaluation of two LAIV strains against potentially pandemic H2N2 influenza virus. PLoS One 9:e102339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabel GJ, Wei CJ, Ledgerwood JE. 2011. Vaccinate for the next H2N2 pandemic now. Nature 471:157–158. doi: 10.1038/471157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DJ, Lapedes AS, de Jong JC, Bestebroer TM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2004. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 305:371–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1097211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caton AJ, Brownlee GG, Yewdell JW, Gerhard W. 1982. The antigenic structure of the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin (H1 subtype). Cell 31:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiley DC, Wilson IA, Skehel JJ. 1981. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature 289:373–378. doi: 10.1038/289373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson IA, Cox NJ. 1990. Structural basis of immune recognition of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Immunol 8:737–771. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuchiya E, Sugawara K, Hongo S, Matsuzaki Y, Muraki Y, Li ZN, Nakamura K. 2001. Antigenic structure of the haemagglutinin of human influenza A/H2N2 virus. J Gen Virol 82:2475–2484. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-10-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naeve CW, Hinshaw VS, Webster RG. 1984. Mutations in the hemagglutinin receptor-binding site can change the biological properties of an influenza virus. J Virol 51:567–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem 69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koel BF, Burke DF, Bestebroer TM, van der Vliet S, Zondag GC, Vervaet G, Skepner E, Lewis NS, Spronken MI, Russell CA, Eropkin MY, Hurt AC, Barr IG, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Smith DJ. 2013. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 342:976–979. doi: 10.1126/science.1244730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koel BF, van der Vliet S, Burke DF, Bestebroer TM, Bharoto EE, Yasa IW, Herliana I, Laksono BM, Xu K, Skepner E, Russell CA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Perez DR, Osterhaus AD, Smith DJ, Prajitno TY, Fouchier RA. 2014. Antigenic variation of clade 2.1 H5N1 virus is determined by a few amino acid substitutions immediately adjacent to the receptor binding site. mBio 5:e01070-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01070-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guarnaccia T, Carolan LA, Maurer-Stroh S, Lee RT, Job E, Reading PC, Petrie S, McCaw JM, McVernon J, Hurt AC, Kelso A, Mosse J, Barr IG, Laurie KL. 2013. Antigenic drift of the pandemic 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus in A ferret model. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003354. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koel BF, Mogling R, Chutinimitkul S, Fraaij PL, Burke DF, van der Vliet S, de Wit E, Bestebroer TM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Smith DJ, Fouchier RA, de Graaf M. 2015. Identification of amino acid substitutions supporting antigenic change of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. J Virol 89:3763–3775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02962-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Myers JL, Bostick DL, Sullivan CB, Madara J, Linderman SL, Liu Q, Carter DM, Wrammert J, Esposito S, Principi N, Plotkin JB, Ross TM, Ahmed R, Wilson PC, Hensley SE. 2013. Immune history shapes specificity of pandemic H1N1 influenza antibody responses. J Exp Med 210:1493–1500. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis NS, Daly JM, Russell CA, Horton DL, Skepner E, Bryant NA, Burke DF, Rash AS, Wood JL, Chambers TM, Fouchier RA, Mumford JA, Elton DM, Smith DJ. 2011. Antigenic and genetic evolution of equine influenza A (H3N8) virus from 1968 to 2007. J Virol 85:12742–12749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05319-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis NS, Russell CA, Langat P, Anderson TK, Berger K, Bielejec F, Burke DF, Dudas G, Fonville JM, Fouchier RA, Kellam P, Koel BF, Lemey P, Nguyen T, Nuansrichy B, Peiris JM, Saito T, Simon G, Skepner E, Takemae N, Consortium E, Webby RJ, Van Reeth K, Brookes SM, Larsen L, Watson SJ, Brown IH, Vincent AL. 2016. The global antigenic diversity of swine influenza A viruses. Elife 5:e12217. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Both GW, Sleigh MJ, Cox NJ, Kendal AP. 1983. Antigenic drift in influenza virus H3 hemagglutinin from 1968 to 1980: multiple evolutionary pathways and sequential amino acid changes at key antigenic sites. J Virol 48:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rota PA, Hemphill ML, Whistler T, Regnery HL, Kendal AP. 1992. Antigenic and genetic characterization of the haemagglutinins of recent cocirculating strains of influenza B virus. J Gen Virol 73:2737–2742. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke DF, Smith DJ. 2014. A recommended numbering scheme for influenza A HA subtypes. PLoS One 9:e112302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith GJ, Bahl J, Vijaykrishna D, Zhang J, Poon LL, Chen H, Webster RG, Peiris JS, Guan Y. 2009. Dating the emergence of pandemic influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:11709–11712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904991106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westgeest KB, de Graaf M, Fourment M, Bestebroer TM, van Beek R, Spronken MI, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Russell CA, Osterhaus AD, Smith GJ, Smith DJ, Fouchier RA. 2012. Genetic evolution of the neuraminidase of influenza A (H3N2) viruses from 1968 to 2009 and its correspondence to haemagglutinin evolution. J Gen Virol 93:1996–2007. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043059-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al Khatib HA, Al Thani AA, Yassine HM. 2018. Evolution and dynamics of the pandemic H1N1 influenza hemagglutinin protein from 2009 to 2017. Arch Virol 163:3035–3049. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3962-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su YC, Bahl J, Joseph U, Butt KM, Peck HA, Koay ES, Oon LL, Barr IG, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ. 2015. Phylodynamics of H1N1/2009 influenza reveals the transition from host adaptation to immune-driven selection. Nat Commun 6:7952. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neher RA, Bedford T, Daniels RS, Russell CA, Shraiman BI. 2016. Prediction, dynamics, and visualization of antigenic phenotypes of seasonal influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E1701–E1709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525578113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulder J, Masurel N. 1958. Pre-epidemic antibody against 1957 strain of Asiatic influenza in serum of older people living in the Netherlands. Lancet 1:810–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(58)91738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Wit E, Spronken MI, Bestebroer TM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2004. Efficient generation and growth of influenza virus A/PR/8/34 from eight cDNA fragments. Virus Res 103:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Stevens DJ, Haire LF, Walker PA, Coombs PJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2009. Structures of receptor complexes formed by hemagglutinins from the Asian influenza pandemic of 1957. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17175–17180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906849106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol 7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro B, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2006. Choosing appropriate substitution models for the phylogenetic analysis of protein-coding sequences. Mol Biol Evol 23:7–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minin VN, Bloomquist EW, Suchard MA. 2008. Smooth skyride through a rough skyline: Bayesian coalescent-based inference of population dynamics. Mol Biol Evol 25:1459–1471. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]