Abstract

Depression is a life-threatening psychiatric disorder and a major public health concern worldwide with an incidence of 5% and a lifetime prevalence of 15%–20%. It is related with the social disability, decreased quality of life, and a high incidence of suicide. Along with increased depressive cases, health care cost in treating patients suffering from depression has also surged. Previous evidence have reported that depressed patients often exhibit altered circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythm involves physical, mental, and behavioral changes in a daily cycle, and is controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus in responding to light and darkness in an environment. Circadian rhythm disturbance in depressive patients causes early morning waking, sleep disturbances, diurnal mood variation, changes of the mean core temperature, endocrine release, and metabolic functions. Many medical interventions have been used to treat depression; however, several adverse effects are noted. This article reviews the types, causes of depression, mechanism of circadian rhythm, and the relationship between circadian rhythm disturbance with depression. Pharmaceutical and alternative interventions used to treat depressed patients are also discussed.

KEYWORDS: Antidepressants, Chronotherapy, Circadian rhythm, Clock genes, Depression

INTRODUCTION

Definition and prevalence of depression

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined depression as a common mental disorder, characterized by sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feeling of guilt or low self-worth, poor concentration, inability to carry out daily activities, disturbed sleep, and loss of appetite. Severe depression even leads to suicide. Around 2%–9% of people who die by committing suicide had histories of suffering from symptoms of major depression. Suicide is the second leading cause of death in the population of the age between 15 and 29 years in low- and middle-income countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, American Regions, African, European, and South-East Asian Regions [1]. According to the report of Minister of Health and Welfare of Taiwan in 2017, the suicide rate of Taiwanese is 16/100,000 population, which is increased and higher than the rate of 15.7/100,000 in 2015 [2]. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the suicidal causes in Taiwan [3]. There are 322 million people affected with depression worldwide in 2015 that is around 4.4% of global population. The total number of people living with depression increased by 18.4% between the years 2005 and 2015. Nearly half of these people live in the South-East Asian Regions and the Western Pacific Regions. The Gender difference is observed in patients suffering from depression. The incidence in females (5.1%) is higher than that in males (3.6%). Besides, the prevalence of depression varies by age, peaking in older adulthood of age between 55 and 74 years. Although with a lower incidence than older age groups, depression also occurs in children and adolescents younger than 15 years old [4].

Classification of depression

According to the International Classification for Disease and Related Disorder-10 published by the WHO, depression disorders are divided into two main subcategories MDD and depressive episode and dysthymia [5]. MDD, also known as unipolar depressive disorder which is characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, and decreased energy. Levels of the depressive episode can be categorized from mild, moderate, to severe [1], which often lasts more than 2 weeks and years in some cases. If the patient does not receive appropriate treatment, the risk of recurrent depressive episodes and dysthymia increased. Dysthymia is characterized as a persistent or chronic form of mild depression in which the symptoms are similar to MDD but last longer, at least 2 years, sometimes decades [4,5].

Pathophysiology of depression

Many factors are involved in the pathophysiology of depression including genetics [6,7], changes in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and stress hormones [8,9], abnormal release or low function of neurotransmitters such as serotonin [10], norepinephrine, dopamine (DA) [11], glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [12], and disturbances of circadian rhythm [13,14]. Sleep disturbance, the major circadian rhythm change, is considered to be important diagnostic criteria for MDD. Around 90% of depressed patients have difficulty falling asleep and maintaining good quality of sleep. Depressive patients have shorter latency between sleep onset and the first episode of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep than healthy people. They also exhibit increased duration and times of eye movements during REM sleep and decreased slow-wave sleep [15,16]. Circadian rhythms are also disturbed in patients affected with mood disorder. They express positive symptoms including over-enthusiasm, happiness, activeness, and alertness, or negative symptoms including distress, fear, anger, guilt, and disgust [17].

Neuroimaging and postmortem studies have provided evidence about brain regions involved in depression. Regional brain imaging studies using magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and single-photon emission computed tomography on depressed patients have shown a reduction of brain volume in the dorsal and medial prefrontal cortex, the dorsal and ventral anterior cingulate cortex, the orbital frontal cortex, and the insula [18]. The structural changes in these brain regions, especially dorsal and medial prefrontal cortex can cause reduction of problem-solving abilities, higher propensity to express negative emotions, and are associated with suicidal behavior [19].

Circadian rhythms and the underlying molecular mechanism

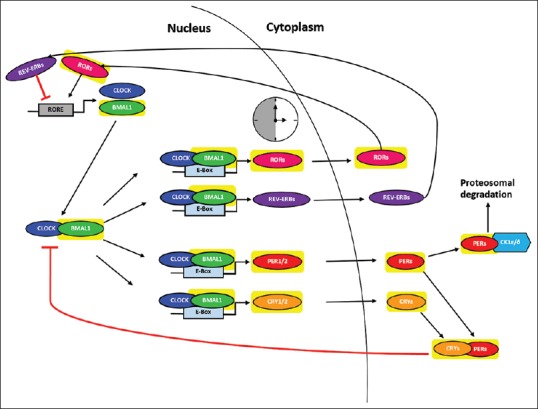

In mammals, the cyclic rhythmicity of a given molecular or biological process produced by oscillator within the 24-h dark-light cycle is called circadian rhythm or circadian clock [14]. The circadian rhythms are regulated by a central pacemaker, which is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus [20]. Molecular mechanism of the circadian rhythm was discovered by Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Micheal W. Young who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2017. Circadian rhythm is mediated by the transcriptional-translational feedback loop of core clock genes (TTLs), which includes the genes Brain muscle ARNT-like1 (Bmal1), Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), Period1 (PER1), PER2, cryptochrome1 (CRY1), and CRY2 [21]. BMAL1 and CLOCK proteins act in a positive feedback loop to regulate the expression of TTLs. They form a heterodimer and binds to enhancer box (E-box) elements, DNA response element with protein-binding site, within the promoter regions of PER, CRY, reverse-related erythroblastoma (REV-ERB), and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (RORs) to activate their transcription during late night and early morning. Whereas, PER and CRY proteins constitute the negative feedback loop of regulating TTLs. They accumulate in the cytoplasm and form complexes that translocate back into the nucleus and inhibit BMAL1/CLOCK-mediated transcription during late day and nighttime. The reactivation of BMAL1/CLOCK proteins occurs when PER and CRY are degraded by ubiquitination systems. In addition, REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptor act in an auxiliary oscillatory feedback loop to regulate Bmal1, stabilizing core feedback loop. REV-ERB proteins exert a negative feedback by inhibiting Bmal1 transcription, while ROR proteins are positive regulators of Bmal1 transcription. RORs compete with REV-ERB for ROR element binding sites of Bmal1 promoter [22].

Circadian rhythm disturbance in depressive patients

The circadian program regulates the daily rhythms of the brain and body. It is found in many organs and individual cells either in central or peripheral levels. In healthy people, the circadian clock involves in many aspects of our physiology including regulation of sleep pattern, feeding behavior, hormone release, blood pressure, and body temperature [23]. The disturbance of circadian rhythm for depressive patients is often indicated with abnormal sleep patterns including shortened latency of REM sleep, increased duration of the first REM period, increased times of eye movements during REM sleep, and decrease of total sleep time. Slow-wave activity, a marker of sleep homeostasis, shown on the electroencephalography (EEG) during non-REM sleep is usually decreased in patients affected with depression [24]. Besides, increased mean core temperature and decreased amplitude of the circadian changes are also found in depressed patients. The change of core temperature during night time is correlated with the release of hormones including thyroid stimulating hormone, norepinephrine, cortisol, and melatonin [25]. In addition, genetic mutations are known to be associated with circadian rhythm disturbance in depressive patients [26,27,28]. Circadian synchronization is critical for maintaining body homeostasis. Circadian synchronization for expression of clock genes is controlled by the natural light-dark rhythm within 24 h. The synchronization of circadian modulates the transcriptional-translational feedback loop of core CLOCK genes such as BMAL1, CLOCK, PER, CRY, REV-ERB, and ROR, which involve physical, mental, and behavior in mammals [29]. The desynchronization (loss of circadian rhythm) of clock genes expression is one pathophysiology of depressive disorder [30,31]. Understanding the factors that trigger desynchronization of core CLOCK genes in depression thus help develop more effective treatment than anti-depressants for patients affected with depressive disorders.

Genes participate in both depression and circadian rhythm

Previous studies have found that several genes are involved in the pathology of depression. The study of whole blood transcriptome by Liliana Ciobanu in 2017 using the Weighted Gene Co-expression Analysis (WGCNA) constructs a network consisting of 29 modules. They demonstrate that two modules of WGCNA are associated with depression symptoms. There are 37 out of 82 genes in one module and 17 out of 64 genes in another module significantly associated with the phenotypes of depression. Among 37 protein-coding genes of the first module, 8 genes related to various translational, metabolic, and immune processes are also associated with depression, including the PCYOX1 L, RPL14, MCTS1, GMAP7, NDUEB9, BOLA2, EIF3M, and RPL7A. Among 17 protein-coding genes in the second module, 5 genes participate in enzymatic, transcriptional, and translational regulation activities [28], are also associated with depression including the PRCP, POLR2J2, TAOK3, EIF2B5, and ATF4. Especially the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), or CREB2, is a transcription factor that plays a critical role in circadian rhythm by binding to the Per2 gene [27]. About 50% to 90% of patients diagnosed with depression complain about bad sleep quality. The circadian rhythm change also contributes to the pathogenesis of winter depression. Evidence show that three circadian clock genes in gene-wise logistic regression analysis including the Arntl, Npas2, and Per2 contribute to winter depression [26]. Another study also reported that the postmortem brains of MDD patients for whom at the recorded hour of death showed less synchronization of circadian rhythm genes between daytime and nighttime such as BMAL1 (ARNTL), PER1-2-3, NR1D1(REV-ERBa), DBP, BHLHE40 (DEC1), and BHLHE41 (DEC2) (25). The study of a population-based sample of the Health 2000 dataset from Finland, including 384 depressed individuals and 1270 controls showed 113 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of 18 genes of the circadian system in depressed patients. Moreover, the researcher found the SNPs of some circadian genes between female and male depressed patients are different. In female depression patients, 14 SNPs from 6 circadian-related genes including TIMELESS, ARNTL, RORA, nuclear factor, interleukin 3 regulated, CSNK1E, and CRY2 were found. In males, 14 SNPs from 6 genes including ARNTL, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like 2 (ARNTL2), RORA, NPAS2, TIPIN, and period homolog 1 (Drosophila) (PER1) were identified [32]. Gender apparently is one important factor that affects the development of depression and abnormal circadian rhythm. Although the treatment of depression and circadian rhythm disturbance has been developed for seven decades, several side effects are still concerned. Therefore, studies on share molecules for depression and circadian rhythm disturbance might lead to alternative, novel therapeutic methods.

TREATMENT FOR CIRCADIAN RHYTHM DISTURBANCE AND DEPRESSION

Antidepressant treatment

Several neurotransmitters including DA, GABA, serotonin, norepinephrine, as well as melatonin, are involved in pathophysiology of depression [10,11,12]. Antidepressants are commonly prescribed to patients as treatments for clinical depression or to prevent recurrence. Several antidepressants also appear to be effective in treating disturbance of circadian rhythm, particularly on sleep disorder. However, aversive side effects including headaches, nausea, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, weight changes, and loss or increase of appetite are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

The properties and side effects of antidepressants that are effective in treating both depression and circadian rhythm disturbance

| Drug | Properties | Side effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimipramine Doxepin Amitriptyline | TCAs Inhibit reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine Insomnia treatment: Trimipramine (50-200 mg), doxepin (3-6 mg), and amitriptyline (10-100 mg) | Sedation, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, and orthostatic hypotension | [33,34,35,36] |

| Paroxetine Fluvoxamine | SSRIs Selectively inhibit reuptake of serotonin Insomnia treatment: Paroxetine (20 mg), fluvoxamine (50 mg) | Sexual functioning, sleepiness, weight gain, agitation, dizziness, dry mouth, nausea, nervousness, headache, vomiting, diarrhea | [37,38,39,40] |

| Mirtazapine Trazodone | Atypical antidepressants Mixed effects on dopamine, serotonin, or norepinephrine Insomnia treatment: Mirtazapine (15-45 mg), Trazodone (150-400 mg) | Headache, agitation, insomnia, loss or increase of appetite, weight loss or gain, sweating, sedation, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness | [41,42,43] |

| Agomelatine | It act on both melatonin and serotonin receptors Insomnia treatment: Without causing daytime sedation (25-50 mg) | Headache, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, somnolence, constipation, and abdominal pain | [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

TCAs: Tricyclic antidepressant, SSRIs: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Chronotherapies

Chronotherapy is a series of nonpharmaceutical and biologically-based clinical interventions including sleep deprivation (also known as wake therapy), sleep phase advance, light and dark therapy [52]. In 1971, the first experiment of chronotherapies was developed in European countries to treat depressed patients with severe insomnia [53]. This technique is in clinical use as antidepressant treatment by controlling sleep rhythm of patients. This treatment has found to be highly effective and causes minimum side effect in depressive patients [54]. Chronotherapy is also reported to be effective on two adolescent patients affected with depression but resistant to antidepressants [55]. Although it appears to be promising, the effect of chronotherapy is transient. Patients would return to abnormal sleep pattern again after the treatment stops for 1 or 2 days [56]. Several studies have reported that sleep phase advance and bright light therapy can improve depressive symptoms and prevent the depression relapsing after sleep deprivation [57,58]. Therefore, chronotherapy has been modified to “adjunctive triple chronotherapy,” which combines wake therapy, sleep phase advance and bright light therapy. The adjunctive triple chronotherapy is practicable and tolerable in acutely suicidal and depressive inpatients [59]. Adjunctive triple chronotherapy combined with antidepressant treatment is reported to prolong the therapeutic effect for about 9 weeks [57].

Animal model for depression and circadian rhythm disturbance

Depression with circadian rhythm change in patients is usually found in clinical observation. Understanding the shared molecular mechanisms underlying these two symptoms are an important theme. However, the study of molecular, biochemical, physiological, and behavioral changes in human are not feasible. Therefore, animal models have been widely used to study and help us understand the pathophysiological mechanism of the disorders and to develop treatments. There are many animal models of depression which also show circadian rhythm changes. Li et al. reported that wild type female mice induced by forced swim test as an acute stress model of depression showed circadian rhythm change in the night phase when compared to male mice [60]. Mice immobilized in the tail suspension test to induce depression exhibiting sleep-wakefulness alterations, which are also observed in depressed patients [61]. Another depression model, the chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) paradigm, is used to study the effects of acute and chronic stresses in mice [62]. This model involves an ethological form of stress related to territorial aggression of mice. For 10 consecutive days, wild-type mice were placed in a cage containing CD1 mice that had been previously screened for aggressive behavior. After that, mice were tested with electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography, body temperature, and locomotor activity. Results show that mice went through CSDS exhibiting persistent sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm change that similarly appear in humans [63]. Genetic manipulation is also used to create the model of depression and circadian rhythm disturbance including the SCN-specific Bmal1-knockdown mice [64], Per2 knockout mice [65], and Per3 knockout mice [66].

CONCLUSION

Several evidence have suggested that circadian rhythm disturbance may play a major role in the pathophysiology of depression. The molecular, biochemical, physiological, and behavioral changes link circadian rhythm disturbance with depression. The molecules involved in circadian rhythm disturbance and depression have been well studied, however, pathways that link the two disorders are not clear yet. The transcriptional regulation circuit of clock genes in mammals is illustrated in Figure 1. Among them, we labeled those genes also known to be involved in depression with yellow background. They may play important roles in linking depression and circadian rhythm.

Figure 1.

The transcriptional regulation circuit of clock genes in mammal. Circadian rhythm is mediated by the genes Brain muscle ARNT-like1 and circadian locomotor output cycles kaput act in a positive feedback loop to regulate expression of the transcriptional-translational feedback loop of core clock genes during late night and early morning. They form a heterodimer and binds to enhancer box elements, DNA response element with protein-binding site, within the promoter regions of Period, CRY, REV-ERB, and RORs. Period and CRY accumulate in the cytoplasm and form complexes that translocate back into the nucleus and inhibit brain muscle ARNT-like1/circadian locomotor output cycles kaput -mediated transcription during late day and nighttime. In addition, reverse-related erythroblastoma proteins exert a negative feedback by inhibiting Bmal1 transcription, while related orphan receptor proteins are positive regulators of Bmal1 transcription. Related orphan receptors compete with reverse-related erythroblastoma for related orphan receptor element binding sites of Bmal1 promoter. The genes highlighted in yellow are also involved in depression, however, the pathway that links depression and circadian rhythm disturbance is not delineated yet

Both pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions for circadian rhythm disturbance are effective in treating some depressive patients, however, aversive side effects are noted and 10%–30% of patients are not responsive to the drugs in the market. Researches to delineate molecular pathway(s) that link the two disorders thus become an urgent theme for the development of novel drug target and new therapeutic treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welfare TMoHa. Taiwan health and welfare report 2017. Welfare TMoHa. 2017:180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin YW, Huang HC, Lin MF, Shyu ML, Tsai PL, Chang HJ, et al. Influential factors for and outcomes of hospitalized patients with suicide-related behaviors: A national record study in Taiwan from 1997-2010. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards D. Prevalence and clinical course of depression: A review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levinson DF. The genetics of depression: A review. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: Classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verduijn J, Milaneschi Y, Schoevers RA, van Hemert AM, Beekman AT, Penninx BW, et al. Pathophysiology of major depressive disorder: Mechanisms involved in etiology are not associated with clinical progression. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e649. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumeister A, Konstantinidis A, Stastny J, Schwarz MJ, Vitouch O, Willeit M, et al. Association between serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5HTTLPR) and behavioral responses to tryptophan depletion in healthy women with and without family history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:613–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasler G, Fromm S, Carlson PJ, Luckenbaugh DA, Waldeck T, Geraci M, et al. Neural response to catecholamine depletion in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder in remission and healthy subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:521–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, Meyers N, Shen J, Drevets WC, et al. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:193–200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Hamo M, Larson TA, Duge LS, Sikkema C, Wilkinson CW, de la Iglesia HO, et al. Circadian forced desynchrony of the master clock leads to phenotypic manifestation of depression in rats. eNeuro. 2016;3 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0237-16.2016. pii: ENEURO.0237-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germain A, Kupfer DJ. Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:571–85. doi: 10.1002/hup.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaffery J, Hoffmann R, Armitage R. The neurobiology of depression: Perspectives from animal and human sleep studies. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:82–98. doi: 10.1177/1073858402239594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1254–69. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtet P, Olié E. Circadian dimension and severity of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(Suppl 3):S476–81. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandya M, Altinay M, Malone DA, Jr, Anand A. Where in the brain is depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:634–42. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0322-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desmyter S, van Heeringen C, Audenaert K. Structural and functional neuroimaging studies of the suicidal brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:796–808. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker-Krail D, McClung C. Implications of circadian rhythm and stress in addiction vulnerability. F1000Res. 2016;5 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7608.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoyama S, Shibata S. The role of circadian rhythms in muscular and osseous physiology and their regulation by nutrition and exercise. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:63. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho CH. Molecular mechanism of circadian rhythmicity of seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:55. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2012.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nechita F, Pîrlog MC, ChiriŢă AL. Circadian malfunctions in depression – Neurobiological and psychosocial approaches. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:949–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nutt D, Wilson S, Paterson L. Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:329–36. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/dnutt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koenigsberg HW, Teicher MH, Mitropoulou V, Navalta C, New AS, Trestman R, et al. 24-h monitoring of plasma norepinephrine, MHPG, cortisol, growth hormone and prolactin in depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partonen T, Treutlein J, Alpman A, Frank J, Johansson C, Depner M, et al. Three circadian clock genes per2, arntl, and npas2 contribute to winter depression. Ann Med. 2007;39:229–38. doi: 10.1080/07853890701278795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koyanagi S, Hamdan AM, Horiguchi M, Kusunose N, Okamoto A, Matsunaga N, et al. CAMP-response element (CRE)-mediated transcription by activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) is essential for circadian expression of the period2 gene. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32416–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciobanu L, Sachdev PS, Trollor JN, Reppermund S, Thalamuthu A, Mather KA, et al. Genome-wide gene expression signature of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:S484. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husse J, Eichele G, Oster H. Synchronization of the mammalian circadian timing system: Light can control peripheral clocks independently of the SCN clock: Alternate routes of entrainment optimize the alignment of the body's circadian clock network with external time. Bioessays. 2015;37:1119–28. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam RW. Addressing circadian rhythm disturbances in depressed patients. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:13–8. doi: 10.1177/0269881108092591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wirz-Justice A. Biological rhythm disturbances in mood disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S11–5. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000195660.37267.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utge SJ, Soronen P, Loukola A, Kronholm E, Ollila HM, Pirkola S, et al. Systematic analysis of circadian genes in a population-based sample reveals association of TIMELESS with depression and sleep disturbance. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazarian PK, Park SH. Antidepressant management of insomnia disorder in the absence of a mood disorder. Ment Health Clin. 2014;4:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katwala J, Kumar AK, Sejpal JJ, Terrence M, Mishra M. Therapeutic rationale for low dose doxepin in insomnia patients. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:331–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillman PK. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:737–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Hajak G, Rüther E, et al. Trimipramine in primary insomnia: Results of a polysomnographic double-blind controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35:165–74. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cascade E, Kalali AH, Kennedy SH. Real-world data on SSRI antidepressant side effects. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2009;6:16–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westenberg HG, Sandner C. Tolerability and safety of fluvoxamine and other antidepressants. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:482–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: Adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:22–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nowell PD, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Kupfer DJ. Paroxetine in the treatment of primary insomnia: Preliminary clinical and electroencephalogram sleep data. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:89–95. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santarsieri D, Schwartz TL. Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: A quick guide for clinicians. Drugs Context. 2015;4:212290. doi: 10.7573/dic.212290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thase ME. Antidepressant treatment of the depressed patient with insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 17):28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scharf MB, Sachais BA. Sleep laboratory evaluation of the effects and efficacy of trazodone in depressed insomniac patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Agomelatine: A novel antidepressant. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8:10–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin GM, Emsley R, Rembry S, Rouillon F. Agomelatine Study Group. Agomelatine prevents relapse in patients with major depressive disorder without evidence of a discontinuation syndrome: A 24-weekrandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1128–37. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubovsky SL, Warren C. Agomelatine, a melatonin agonist with antidepressant properties. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1533–40. doi: 10.1517/13543780903292634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein DJ, Ahokas AA, de Bodinat C. Efficacy of agomelatine in generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:561–6. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318184ff5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.San L, Arranz B. Agomelatine: A novel mechanism of antidepressant action involving the melatonergic and the serotonergic system. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dolder CR, Nelson M, Snider M. Agomelatine treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1822–31. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pjrek E, Winkler D, Konstantinidis A, Willeit M, Praschak-Rieder N, Kasper S, et al. Agomelatine in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:575–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montgomery SA, Kasper S. Severe depression and antidepressants: Focus on a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled studies on agomelatine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:283–91. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280c56b13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:509–22. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Sleep deprivation in depression: What do we know, where do we go? Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:445–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leibenluft E, Wehr TA. Is sleep deprivation useful in the treatment of depression? Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:159–68. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casher MI, Schuldt S, Haq A, Burkhead-Weiner D. Chronotherapy in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Ann. 2012;42:166–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu JC, Bunney WE. The biological basis of an antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and relapse: Review and hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:14–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martiny K, Refsgaard E, Lund V, Lunde M, Sørensen L, Thougaard B, et al. A 9-week randomized trial comparing a chronotherapeutic intervention (wake and light therapy) to exercise in major depressive disorder patients treated with duloxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1234–42. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Echizenya M, Suda H, Takeshima M, Inomata Y, Shimizu T. Total sleep deprivation followed by sleep phase advance and bright light therapy in drug-resistant mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2013;144:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sahlem GL, Kalivas B, Fox JB, Lamb K, Roper A, Williams EN, et al. Adjunctive triple chronotherapy (combined total sleep deprivation, sleep phase advance, and bright light therapy) rapidly improves mood and suicidality in suicidal depressed inpatients: An open label pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;59:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li N, Xu Y, Chen X, Duan Q, Zhao M. Sex-specific diurnal immobility induced by forced swim test in wild type and clock gene deficient mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:6831–41. doi: 10.3390/ijms16046831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El Yacoubi M, Bouali S, Popa D, Naudon L, Leroux-Nicollet I, Hamon M, et al. Behavioral, neurochemical, and electrophysiological characterization of a genetic mouse model of depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6227–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1034823100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golden SA, Covington HE, 3rd, Berton O, Russo SJ. A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1183–91. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wells AM, Ridener E, Bourbonais CA, Kim W, Pantazopoulos H, Carroll FI, et al. Effects of chronic social defeat stress on sleep and circadian rhythms are mitigated by kappa-opioid receptor antagonism. J Neurosci. 2017;37:7656–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0885-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Landgraf D, Long JE, Proulx CD, Barandas R, Malinow R, Welsh DK, et al. Genetic disruption of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus causes helplessness, behavioral despair, and anxiety-like behavior in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:827–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.03.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hampp G, Ripperger JA, Houben T, Schmutz I, Blex C, Perreau-Lenz S, et al. Regulation of monoamine oxidase A by circadian-clock components implies clock influence on mood. Curr Biol. 2008;18:678–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang L, Hirano A, Hsu PK, Jones CR, Sakai N, Okuro M, et al. A PERIOD3 variant causes a circadian phenotype and is associated with a seasonal mood trait. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1536–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600039113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]