Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study was to test the effect of TNF484 on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells.

Materials and Methods:

Various doses (0, 1, 10, 50, and 100 nM) of TNF484 were applied to the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells, and cell proliferation was measured by using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay after 72 h. Cell migration rate was measured using the xCELLigence system, and the cell invasion ability was examined by the three-dimensional spheroid BME cell invasion assay. The expression level of ADAM17 was also measured with RT-PCR.

Results:

With the treatment of TNF484, the cell proliferation of HepG2 and Bel7402 cells was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, under TNF484 treatment, the cell migration rate as well as cell invasion ability of the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells were suppressed.

Conclusion:

TNF484 could inhibit the cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of some HCC cell lines, making it a potential therapeutic option for liver cancer treatment.

Keywords: ADAM17, hepatocellular carcinoma, TNF484

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a very common type of malignancy. Due to its high degree of malignancy and the difficulties in early clinical diagnosis, it is a serious threat to human health. At present, it is mainly occurred in Africa and South Asia and also increased year-by-year in many Western countries.[1,2,3] The metastasis of liver cancer is a major cause of clinical treatment failure and contributes to the high mortality rate of the disease. Therefore, to restrain and control the cancer metastasis is the major strategy of the prevention and treatment of liver cancer.

Tumor invasion and metastasis are a process of the malignant cells involving many steps such as migrating from the primary tumor sites to the extracellular matrix (ECM), degrading and passing through the ECM and base membrane, and moving through the blood vessels into the host microenvironment. The ECM-degrading enzyme system, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) family and integrin-matrix metalloproteinase family (a disintegrin and metalloproteases [ADAMs]), contributes to the invasion and metastasis process.[4,5] ADAM17, a member of the ADAMs, is the first “sheddase” identified in 1997, also known as tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme.[6,7] Due to its ability to process tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) for release from the cell membrane as well as its enzymatic hydrolysis of multiple ligands to activate the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway, ADAMl7 is closely related to cancer invasion.[8,9,10,11,12,13] Abundant studies have shown that ADAM17 is overexpressed in various tumors, and facilitates the process of tumor invasion and metastasis.[12,13,14,15] Therefore, ADAM17 may be potential targets for the treatment of a variety of cancers.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19] ADAM17 inhibitors are now under fast development, and some of them are proven to be potentially effective for the treatment of several cancers such as lung cancer, breast cancer, head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma, and lymphoma.[17] However, few study has investigated the role of ADAM17 inhibition in HCC.

It has been reported that ADAM17 accelerated tumor cell proliferation of HCC cell lines through the regulation of the angiotensin II and EGFR signaling.[20] The mRNA expression level of ADAM17 in HCC tissues was found significantly higher than that in paired normal liver tissues.[21] Notably, ADAMA17 expression was much higher in HCC subtype with lower differentiation and higher malignancy. It suggests that the increased mRNA expression level of ADAM17 may play an important role in the HCC development.[21] ADAM17 expression level was also found to be elevated in hypoxia-treated HCC cells, and it mediated hypoxia-induced drug resistance in HCC through activating the EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway.[22] A recent study found that ADAM17 may function in maintaining the metastatic capabilities of liver cancer stem cells.[23] Overexpression of miR-145, which targets ADAM17, suppresses cell invasion of HCC cells.[24] Thus, ADAM17-targeting therapeutics may provide a potential option in liver cancer treatment. In this study, we will detect the effect of TNF484, an ADAM17 inhibitor, on the cell proliferation, migration, and invasion ability of HCC cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell and cell culture

The human hepatoma cell line HepG2 cells and Bel7402 cells (Shanghai Institute of life sciences, Shanghai, PRC) are cultured in DMEM medium (GIBCO, USA), with 10% of fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, USA), 2 mM glutamine, 100U/ml of penicillin, and 100 ug/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in the incubator with 5% CO2 and 70%–75% humidity. The medium was changed every 72 h.

Cell viability assays

A number of 1 × 104 HepG2 and Bel7402 cells were suspended into each well in 96-well plates, various doses of inhibitor were added (99% purity; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated for 72 h at 37°C incubator, with normal cultured cells as a negative control. After incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 20 ul of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/ml; Sigma Aldrich) and incubated for another 4 h. The 96-well plate was centrifuged at 1200 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully removed, and 50 ul of dimethyl sulfoxide was added into the 96-well plate, followed by incubation in the orbital shaker for 10 min. MTT was measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay apparatus under 490-nm absorbance, and formulas were used to calculate effects on cell proliferation. Inhibition (inhibition ratio) = (1 − average OD value of test group/average OD value of control group) × 100%.

ADAM17 expression analysis by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Cells (1 × 105) were seeded in six-well plates and allowed overnight. Then, the cells were cultured for 72 h in the presence of 1 uM of TNF484, with no TNF484 as a control. The total RNA was extracted as described in TRIzol Reagent Kit, and then reverse transcripted into cDNA, which was used as a template for ADAM17 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene amplification. The primers for ADAM17 and GAPDH amplification are summarized in Table 1. RT-PCR reaction conditions as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20 s, annealing at 60°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 40 s.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Gene name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| ADAM17 | Forward 5’GGTGGTAGCAGATCATCGCTT3’ |

| Reverse 5’GTGGAGACTTGAGAATGCGAA3’ | |

| GAPDH | Forward 5’CCCCTTCATTGACCTCAACT3’ |

| Reverse 5’ATGAGTCCTTCCACGATACC3’ |

Migration assays

The migration capacity of HCC cells was examined using the xCELLigence system (ACEA Biosciences Inc.). Cells were suspended with DMEM medium containing 2% serum, and 200 ul of cell suspension (2 × 104) was added into the upper chamber of CIM-16 plate. 10 nm of TNF484 was also added in the upper chamber, with none TNF484 as a negative control. Then, 10% serum-containing DMEM medium was added into the lower chamber. The migration rate was assessed by measuring electrical impedance along the gold coated underside of the membrane which separated the two chambers. A greater level of electrical impedance was determined as an amplified migratory rate as analyzed on the real-time cell analyzer over a 72-h period (ACEA Biosciences Inc.).

Invasion assay

Three-dimensional (3D) spheroid BME cell invasion assay (Trevigen) was used to determine the inhibition of the invasive ability by TNF484 in HCC cells. The preparation of spheroid and the invasive matrix was in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were suspended with DMEM and spheroid matrix, and 5 × 102 cells were added into each well of 3D spheroid culture plate. The plate was centrifuged at 200 g for 3 min at 4°C and incubated at 37°C for 72 h to let the spheroid form. Then, invasive matrix was added into the plate, followed by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min at 4°C. The plate was put into 37°C incubator for 1 h to allow invasive matrix gel formation. 1 uM of TNF484 was added in the well, and the images of the spheroid were recorded every 24 h. Images were analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The degree of invasiveness was measured as the total area of the spheroid's reach.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Three repeats (n = 3) were set for each group in every assay. Student's t-test (two-tailed) and one-way analysis were used for statistical analysis of the studies. Data were shown as the mean ± SD. Significant differences between the groups were indicated by * for P < 0.05, ** for P < 0.01, and *** for P < 0.001, respectively.

RESULTS

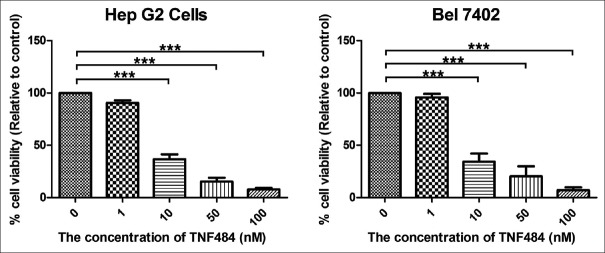

TNF484 inhibited cell viability of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

To evaluate the effect of ADAM17 inhibitors on liver cancer cells, we use the MTT assay to determine the cytotoxicity of TNF484 in various HCC cell lines (HepG2 and Bel7402). TNF484 showed the significant inhibitory effect on the proliferation of the HCC cells when the concentration reached 10 nM (P < 0.001), and the proliferation rate was 35.88% ± 5.3% and 34.62% ± 8.5% compared to the untreated control for HepG2 and Bel7402 cells, respectively [Figure 1]. With the increasing concentration of inhibitors, the inhibition rate was also increased. The results showed that the inhibition of the proliferation of liver cancer cells was dose dependent.

Figure 1.

TNF484 inhibits cell viability of two liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Bel7402. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates in triplicate for overnight incubation, followed by treatment with various concentration of TNF484 for 72 h to assess their effect on cell viability. Data are expressed as percentage viability compared to untreated control cells ± standard deviation (***P < 0.001)

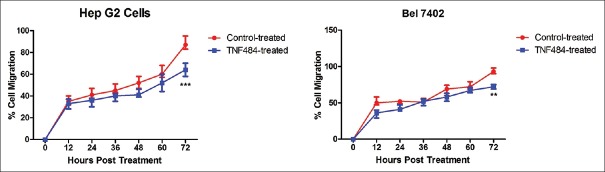

TNF484 inhibited cell migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

Cell migration is an important characteristic of liver cancer cells. We use the xCELLigence real-time migration system to examine if TNF484 can reduce the migration of hepatocarcinoma cells. After 72 h’ treatment, cell migration rate for the TNF484-treated HepG2 cells was 64.00% ± 3.53% and control HepG2 cells was 88.33% ± 6.11% [Figure 2], showing that TNF484 significantly inhibited the migration of HepG2 cells (P < 0.001). We have also tested the cell migration with Bel7402 cells and found that after 72-h treatment, cell migration rate was 72.00% ± 3.00% for the TNF484-treated group and 93.67% ± 4.04% for the control group [Figure 2]. Similar to the HepG2 cells, TNF484 showed significant inhibition on the migration of Bel7402 cells (P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

TNF484 inhibits cell migration of two liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Bel7402. The cells were seeded into CIM-16 xCELLigence plates and treated with 10 nM of TNF484 in triplicate. Cell migration was assessed over 72 h, measuring the relative mean impedance (cell index) for control-treated (red line) and TNF484-treated cells (blue line). Data shown are mean relative percentage migration from duplicate wells ± standard deviation ( ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

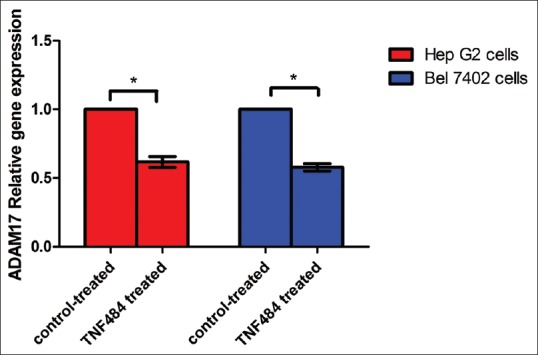

TNF484 inhibited expression of ADAM17 in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

ADAM17 is expressed in tumor cells and secreted into the extracellular environment to mediate degradation of ECM, making tumor cells more migratable to the surrounding tissues. We have found that TNF484 inhibited the migration of hepatocarcinoma cells; then, we also examined the expression of ADAM17 in different liver cancer cells with TNF484 treatment. The results showed that under the treatment of 1 uM TNF484, the mRNA expression level of ADAM17 was 61.66% ± 3.98% and 58.10% ± 3.27% related to the untreated control for the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells, respectively. It suggested that TNF484 treatment reduced the expression of ADAM17 in hepatocarcinoma cells (P < 0.05) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Relative expression level of ADAM17 mRNAs in HepG2 and Bel7402 cells. Expression of ADAM17 mRNAs was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The expression of ADAM17 mRNAs in the control group was arbitrarily defined as 1 (*P < 0.05)

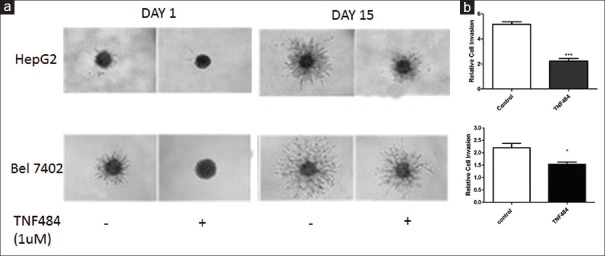

TNF484 inhibited cell invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

The hepatocarcinoma cells have a strong ability of invasion and metastasis; therefore, it is particularly important to find a component that could inhibit the invasion ability of HCC cells. We used 3D invasion assay to determine the inhibitory effect of TNF484 on liver cancer cell invasion. In the control group, cells were cultured for 15 days without TNF484, and the cell balls were significantly bigger than that at day 1, with the relative cell invasion rate 5.17 ± 0.35 and 2.20 ± 0.30 for the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells, respectively. It suggested that the two hepatocarcinoma cell lines have strong invasion ability. While in the group treated with TNF484, cell invasion rate was 2.23 ± 0.35 and 1.53 ± 0.15 for the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells, respectively. It suggested that TNF484 inhibited the cell invasion ability of the two HCC cells [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

TNF484 inhibits cell invasion of two liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Bel7402. The cells were seeded into three-dimensional invasion assay plates as described in Materials and Methods and treated with 1 uM of TNF484 in triplicate. (a) Images were taken every day for 15 days with cell invasion images displayed for day 1 and day 15. (b) Relative invasion after 15 days’ treatment with or without TNF484. Data shown are relative invasion to the day 1 control samples from triplicate wells ± standard deviation (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001)

DISCUSSION

Cancer metastasis is a primary feature of malignant tumors, which is also the most important step for cancer development. The massive metastasis in the late stage of liver cancer is the main reason for its high mortality rates. Hence, finding a drug that can inhibit the growth, invasion, and metastasis of HCC is the key for effective liver cancer treatment. Some natural compounds have been demonstrated to be able to inhibit the growth of HCC cells.[25] However, more lead molecules are still in urgent need to drive the drug development for liver cancer. In this study, we found that TNF484, an ADAM17 inhibitor, could inhibit HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.

ADAM17 is known to process single transmembrane proteins such as cytokines, growth factors, receptors, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. To date, it has over 80 substrates, and most of them are implicated in physiological and pathological processes including inflammation, tumor growth, and tumor metastasis.[26] While ADAM17 has a wide variety of substrates, it is only activated on pathological stimuli, making it an attractive target for intervention of diseases including inflammation and cancers.[17] The development of various ADAM17 inhibitors has seen great progress in recent years.[17,18] While antibodies and prodomains of ADAM17 show high selectivity to ADAM17, small molecules are still the most important agents targeting ADAM17, and some of them were tested in clinical trials. INCB7839, a dual inhibitor of ADAM17 and ADAM10, is now under clinical trial in combination with rituximab for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[17] INCB7839 was also demonstrated to inhibit the shedding of HER2, and INCB7839 in combination with trastuzumab increased the response rate in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients.[27,28] INCB3619, another potent inhibitor of ADAM17 and ADAM10, was found to decrease tumor growth in non-small lung cancer and breast cancer models.[29] Some other compounds with higher selectivity for ADAM17 inhibition have been developed and are currently being advanced into preclinical studies.[30,31]

TNF484 is a novel water-soluble small molecule inhibitor of ADAM17, which also targets several MMPs (MMP-1, -2, -3, -9, and -13).[32,33] The water solubility of TNF484 largely increases the possibility of practical use in potential therapeutic treatment. This compound has been reported with inhibitory activity for TNF-α release from cells at low nanomolar concentrations in vitro.[32,33] To date, the reported activity of TNF484 in vivo has been focused on inflammation. Trifilieff et al. have demonstrated that TNF484 has activity in lung inflammation.[33] Meli et al. had investigated the effects of TNF484 in a neonatal rat model of pneumococcal meningitis and found that at 1 mg/kg q6 h TNF484 reduced soluble TNF-α and the collagen degradation product hydroxyproline in the cerebrospinal fluid and that TNF484 attenuated the incidence of seizures and injury of the cerebral cortex.[34] It was also reported by another group that adjuvant TNF484 treatment with antibiotic significantly improves the outcome of TLR2−/− mice with experimental pneumococcal meningitis.[35] The effect of TNF484 on ADAM17 inhibition has also been studied in renal fibrosis. ADAM17 was found to be upregulated in renal fibrosis, where it mediated heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) shedding. Inhibition of ADAM17 with TNF484 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of HB-EGF shedding in vitro and significantly reduced the number of glomerular and interstitial macrophages in vivo.[36] These studies have suggested TNF484 as a promising way of intervention in inflammation-related diseases.

Despite the massive implication of ADAM17 in tumor growth and tumor metastasis, there has not been any report regarding the effect of TNF484 on cancer cells yet. In this study, we investigated the effects of TNF484 on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells for the first time. We found that TNF484 inhibited HCC cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner. The TNF484 inhibition of ADAM17 activity may attenuate the shedding of growth factors and other signaling molecules, thus lead to the suppressed cell proliferation. This is consistent with previous studies that TNF484 was potent inhibitors of TNF-α release from human peripheral blood mononuclear cell when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon gamma and that it reduced soluble TNF-α in the bronchoalveolar lavage of LPS challenged mice and cerebrospinal fluid of rat model of pneumococcal meningitis.[33,34] We also found that TNF484 inhibited the cell migration and invasion of the HepG2 and Bel7402 cells. This may due to that TNF484 inhibits the ADAM17 hydrolysis activity of ECM containing collagen and gelatin, and the less degraded ECM thus restrains the mobility and invasiveness of the HCC cells. This is consistent with the previous study that TNF484 reduced the collagen degradation product hydroxyproline in the cerebrospinal fluid.[34]

CONCLUSION

This study supports that TNF484, as an inhibitor of ADAM17, could inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells. Further studies are needed to verify the potential of TNF484 as an HCC therapeutic option.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Lau M, Eschbach K, Davila J, Goodwin J. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanics in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1983–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Lu Y, Rong C, Yang D, Li S, Qin X. Role of superoxide dismutase in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:94. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.192510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochizuki S, Okada Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:621–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–33. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, Bickett DM, Burkhart W, Carter HL, et al. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385:733–6. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zunke F, Rose-John S. The shedding protease ADAM17: Physiology and pathophysiology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864:2059–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borrell-Pagès M, Rojo F, Albanell J, Baselga J, Arribas J. TACE is required for the activation of the EGFR by TGF-alpha in tumors. EMBO J. 2003;22:1114–24. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, Zhou HM, Higashiyama S, Peschon J, et al. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:769–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosur V, Farley ML, Burzenski LM, Shultz LD, Wiles MV. ADAM17 is essential for ectodomain shedding of the EGF-receptor ligand amphiregulin. FEBS Open Bio. 2018;8:702–10. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumgart A, Seidl S, Vlachou P, Michel L, Mitova N, Schatz N, et al. ADAM17 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor expression through the activation of Notch1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5368–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen H, Li L, Zhou S, Yu D, Yang S, Chen X, et al. The role of ADAM17 in tumorigenesis and progression of breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:15359–70. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5418-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant NB, Voskresensky I, Rogers CM, Lafleur B, Dempsey PJ, Graves-Deal R, et al. TACE/ADAM-17: A component of the epidermal growth factor receptor axis and a promising therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1182–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mustafi R, Dougherty U, Mustafi D, Ayaloglu-Butun F, Fletcher M, Adhikari S, et al. ADAM17 is a tumor promoter and therapeutic target in western diet-associated colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:549–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGowan PM, Mullooly M, Caiazza F, Sukor S, Madden SF, Maguire AA, et al. ADAM-17: A novel therapeutic target for triple negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:362–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss ML, Minond D. Recent advances in ADAM17 research: A promising target for cancer and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:9673537. doi: 10.1155/2017/9673537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossello A, Nuti E, Ferrini S, Fabbi M. Targeting ADAM17 sheddase activity in cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:1908–27. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160727143618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullooly M, McGowan PM, Crown J, Duffy MJ. The ADAMs family of proteases as targets for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:870–80. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1177684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itabashi H, Maesawa C, Oikawa H, Kotani K, Sakurai E, Kato K, et al. Angiotensin II and epidermal growth factor receptor cross-talk mediated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease accelerates tumor cell proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:601–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding X, Yang LY, Huang GW, Wang W, Lu WQ. ADAM17 mRNA expression and pathological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2735–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i18.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang XJ, Feng CW, Li M. ADAM17 mediates hypoxia-induced drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through activation of EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;380:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SW, Hur W, Choi JE, Kim JH, Hwang D, Yoon SK. Role of ADAM17 in invasion and migration of CD133-expressing liver cancer stem cells after irradiation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:23482–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang XW, Zhang LJ, Huang XH, Chen LZ, Su Q, Zeng WT, et al. MiR-145 suppresses cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells: MiR-145 targets ADAM17. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:551–9. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dastjerdi MN, Kavoosi F, Valiani A, Esfandiari E, Sanaei M, Sobhanian S, et al. Inhibitory effect of genistein on PLC/PRF5 hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:54. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.158914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gooz M. ADAM-17: The enzyme that does it all. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:146–69. doi: 10.3109/10409231003628015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Infante J, Burris HA, Lewis N, Donehower R, Redman J, Friedman S, et al. A multicenter phase Ib study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, biological activity and clinical efficacy of INCB7839, a potent and selective inhibitor of ADAM10 and ADAM17. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(Supp1):S269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tural D, Akar E, Mutlu H, Kilickap S. P95 HER2 fragments and breast cancer outcome. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:1089–96. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.929946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou BB, Peyton M, He B, Liu C, Girard L, Caudler E, et al. Targeting ADAM-mediated ligand cleavage to inhibit HER3 and EGFR pathways in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minond D, Cudic M, Bionda N, Giulianotti M, Maida L, Houghten RA, et al. Discovery of novel inhibitors of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) using glycosylated and non-glycosylated substrates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36473–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapinska AM, Dreymuller D, Ludwig A, Smith L, Golubkov V, Sohail A, et al. SAR studies of exosite-binding substrate-selective inhibitors of A disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) and application as selective in vitro probes. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5808–24. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kottirsch G, Koch G, Feifel R, Neumann U. Beta-aryl-succinic acid hydroxamates as dual inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases and tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2289–93. doi: 10.1021/jm0110993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trifilieff A, Walker C, Keller T, Kottirsch G, Neumann U. Pharmacological profile of PKF242-484 and PKF241-466, novel dual inhibitors of TNF-alpha converting enzyme and matrix metalloproteinases, in models of airway inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1655–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meli DN, Loeffler JM, Baumann P, Neumann U, Buhl T, Leppert D, et al. In pneumococcal meningitis a novel water-soluble inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases and TNF-alpha converting enzyme attenuates seizures and injury of the cerebral cortex. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;151:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Echchannaoui H, Leib SL, Neumann U, Landmann RM. Adjuvant TACE inhibitor treatment improves the outcome of TLR2-/- mice with experimental pneumococcal meningitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulder GM, Melenhorst WB, Celie JW, Kloosterhuis NJ, Hillebrands JL, Ploeg RJ, et al. ADAM17 up-regulation in renal transplant dysfunction and non-transplant-related renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2114–22. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]