Abstract

This study evaluates changes in types of screen time exposure among young children before and after the widespread availability of mobile devices.

There is widespread concern that children are exposed to too much screen time1,2 via increasingly prevalent and accessible mobile devices.3,4 This study assesses young children’s screen time before and after commonly used mobile devices were widely available.

Methods

We estimated young children’s screen time using time diary data from the 1997 and 2014 Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which collects information of a population-based representative sample of American children. There were 1327 and 443 children younger than 6 years who completed the time dairy in 1997 and 2014, respectively. In each survey, the cohort was divided into 2 age groups: 0 to 2 years and 3 to 5 years. Based on the institutional review board policy, this study did not require approval because the data used are publicly available from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and completely deidentified. For this reason, informed consent was not obtained.

In 1997, screen time was defined as time spent on any activity while watching television programs or videotapes, plus time spent on electronic video games and home computer–related activities. By 2014, screen time activities included the use of television, videotapes, digital video disc, game devices, computer, cell phone, smartphone, tablet, electronic reader, and children’s learning devices.

We calculated children’s mean daily screen time (in hours) during a typical week. We present the time spent on dominant device type in both 1997 and 2014 and the time spent on mobiles devices (including cell phones, smartphones, tablets, electronic readers, and children’s learning devices) in 2014.

Lastly, we classified children into high-user and low-user groups based on median screen time within age group and examined differences in individual and family characteristics. All analyses were adjusted for child-level sample weights. The P value level of significance was .05, and all P values were 2-sided.

Results

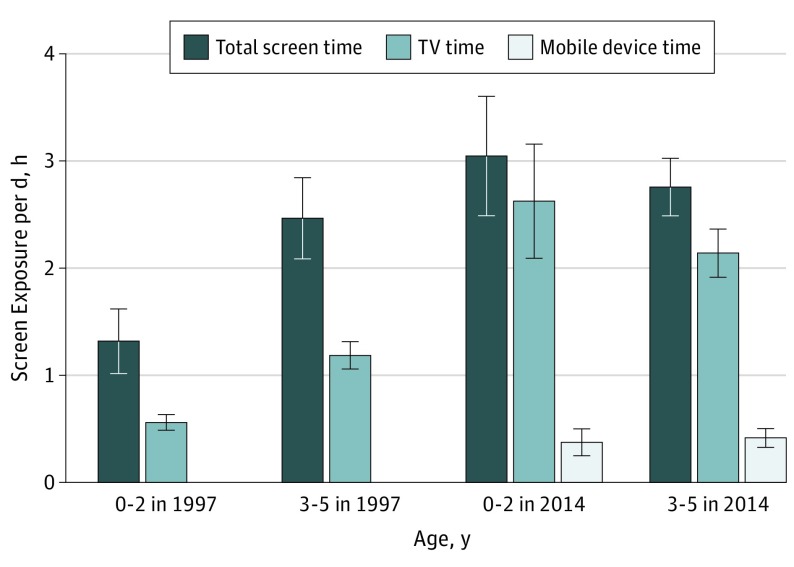

In 1997, daily screen time averaged 1.32 hours for children aged 0 to 2 years and 2.47 hours for children aged 3 to 5 years (Figure). In comparison with other devices, screen time allocated to television was highest; children aged 0 to 2 years and children aged 3 to 5 years watched television for 0.56 and 1.19 hours (43% and 48% of total screen time) per day, respectively.

Figure. Screen Time by Age Group Among 1997 and 2014 Panel Study of Income Dynamics Cohorts.

The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the estimated hours per day. Total screen time in 1997 included time spent on any activity while watching television programs or videotapes plus time spent on electronic video games and home-computer–related activities. Total screen time in 2014 included time spent on any activity while using television, videotapes, digital video disc, game devices, computer, cell phone, smartphone, tablet, electronic reader, and child’s learning devices. Television time refers to time spent on any activity while watching television programs using a television set (rather than using videotapes, digital video disc, or other devices). Mobile device time refers to time spent on any activity while using cell phone, smartphone, tablet, electronic reader, and child’s learning devices.

By 2014, total screen time among children aged 0 to 2 years had risen to 3.05 hours per day. Most of that time (2.62 hours) was spent on television, while 0.37 hours were spent on mobile devices. The older cohort experienced no significant change in total screen time but an increase of about 80% in television time. On average, children aged 3 to 5 years spent 2.14 hours on television and 0.42 hours on mobile devices. In 2014, television time accounted for 86% and 78% of total screen time for the age groups of 0 to 2 years and 3 to 5 years, respectively.

In 1997 and 2014, the low-user group had higher family income (Table). Among other family characteristics, significant differences across user groups were found in age, race/ethnicity, employment status of primary caregiver, and number of children in the household in 1997 and in sex, education level of family unit head and spouse, and metropolitan area residence in 2014.

Table. Characteristics of High and Low Screen Users Among 1997 and 2014 PSID Cohortsa.

| Characteristic | 1997 | 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User, Mean (SE),a % | P Valueb | User, Mean (SE),a % | P Valueb | |||

| High (n = 653) | Low (n = 674) | High (n = 221) | Low (n = 222) | |||

| Age, y | 3.30 (0.07) | 2.85 (0.09) | <.001 | 3.85 (0.11) | 3.88 (0.11) | .87 |

| Female | 46.49 (2.61) | 50.53 (2.42) | .26 | 39.83 (4.42) | 54.80 (4.52) | .02 |

| White | 65.22 (2.50) | 68.07 (2.23) | .40 | 73.58 (4.00) | 81.52 (3.73) | .15 |

| Black | 16.82 (1.87) | 11.27 (1.13) | .01 | 19.64 (2.94) | 15.47 (3.30) | .35 |

| Hispanic | 9.89 (1.56) | 12.26 (1.71) | .31 | NAc | NAc | NA |

| Other races/ethnicities | 8.07 (1.64) | 8.40 (1.51) | .88 | NAc | NAc | NA |

| Enrolled in daycare/school | 40.78 (2.59) | 43.67 (2.40) | .41 | 52.86 (4.65) | 64.46 (4.38) | .07 |

| With 2 parents | 72.66 (2.36) | 77.50 (2.03) | .12 | 73.96 (3.88) | 70.34 (4.25) | .53 |

| Excellent/very good health | 87.23 (1.72) | 83.78 (1.75) | .16 | 91.18 (2.69) | 93.07 (2.12) | .58 |

| Family unit | ||||||

| Household head with bachelor’s degree | 25.77 (2.32) | 29.98 (2.21) | .19 | 26.39 (4.03) | 56.28 (4.54) | <.001 |

| Spouse with bachelor’s degree | 20.03 (2.09) | 25.57 (2.11) | .06 | 21.32 (3.67) | 50.61 (4.59) | <.001 |

| Income/FPL | 2.57 (0.12) | 3.10 (0.15) | .01 | 2.58 (0.18) | 3.79 (0.26) | <.001 |

| PCG employed | 49.63 (2.61) | 57.09 (2.42) | .04 | 57.91 (4.62) | 68.82 (4.14) | .08 |

| Children in HH, No. | 2.25 (0.06) | 2.08 (0.05) | .03 | 2.30 (0.11) | 2.03 (0.10) | .08 |

| Metro area | 70.23 (2.47) | 72.16 (2.27) | .57 | 85.45 (2.93) | 75.85 (3.61) | .04 |

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; HH, household; PCG, primary caregiver; PSID, Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

High and low users are defined, respectively, as children who had screen time greater than and less than median hours within their age group.

P values are from the adjusted Wald test for differences between high and low users.

Because of small sample size, the results were not reported.

Discussion

This study examines young children’s screen time based on time diary data. Such data are shown to be highly associated with directly observed use of time, whereas time use reported via parent surveys, such as those used in the Common Sense Census and other studies,3,4 is only moderately associated with direct observation.5 We found that, between 1997 and 2014, screen time doubled among children aged 0 to 2 years and that, both before and after the advent of mobile devices, young children’s television time increased tremendously. The 2014 high-user group was dominated by boys and children with low parental education level and family income. Future research should examine the association between screen time and other Child Development Supplement measures, such as parenting style and sibling and peer influence. Meanwhile, as stakeholders warn against an overreliance on mobile devices, they should be mindful that young children spend most of their screen time watching television.

References

- 1.American Acemedy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics announces new recommendations for children’s media use. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/American-Academy-of-Pediatrics-Announces-New-Recommendations-for-Childrens-Media-Use.aspx. Published October 21, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 2.Ponti M, Bélanger S, Grimes R, et al. ; Canadian Paediatric Society, Digital Health Task Force, Ottawa, Ontario . Screen time and young children: promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22(8):461-477. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, et al. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1044-1050. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rideout V. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandewater EA, Lee S-J. Measuring children’s media use in the digital age: issues and challenges. Am Behav Sci. 2009;52(8):1152-1176. doi: 10.1177/0002764209331539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]