Abstract

This analysis of 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health data estimates the national and state-level prevalence of treatable mental health disorders and mental health care use in US children.

In children, mental health disorders have deleterious consequences on individual and socioeconomic factors1 and can impede healthful transitioning into adulthood,2 and the incidence of mental health disorders has been increasing over the decades.3 Recent initiatives led by global and national agencies were created to identify priority focus areas regarding the mental health–related burden. Some of the emerging priorities included developing child mental health policies, implementing prevention and early intervention strategies for transition-age youth, and reducing disparities for mental health care use.4 This study sought to inform these initiatives by providing recent national and state-level estimates of the prevalence of treatable mental health disorders and mental health care use in children.

Methods

Data were from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health, a nationally representative, parent-proxy survey of US children younger than 18 years.5 The completion rate for those who initiated the web-based and mail-based survey instruments was 69.7%, with an overall response rate of 40.7%. A total of 50 212 surveys representing US children aged 0 to 17 years were completed.

Parents responded to the prompt, “Has a doctor or other health care provider EVER told you that this child has” a mental health disorder? If yes, parents responded to the prompt, “If yes, does this child CURRENTLY have the condition?” A mental health disorder was considered if the respondent reported yes to the second prompt for depression, anxiety problems, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared with no from the first or second prompt for these conditions. Mental health care use in the last year in children with at least 1 mental health disorder was determined by the prompt, “DURING THE PAST 12 MONTHS, has this child received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional? Mental health professionals include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and clinical social workers.”

Weighted prevalence estimates were calculated using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) to account and adjust for the complex survey design. Logistic regression determined the association between mental health disorders and covariates. Covariates were selected based on their relevance to children and outcomes, availability in National Survey of Children’s Health, and the extent of missingness to avoid data truncation (<2%). The prevalence of the 2 outcome measures were transformed into quartiles to determine state-specific disparities. Children without current health insurance and younger than 6 years were excluded. Prevalence estimates were compared between those with and without mental health disorders using χ2 test. All P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set at a P value less than .05.

Results

An estimated 46.6 million children were included for analysis. The national prevalence of at least 1 mental health disorder was 16.5% (weighted estimate, 7.7 million). After adjustments, all covariates were associated with mental health disorders except for continuous insurance (Table). The state-level prevalence of at least 1 mental health disorder ranged from 7.6% (Hawaii) to 27.2% (Maine).

Table. Characteristics of Participants and Adjusted Associations With Mental Health Disorders.

| Variable | Mental Health Disorder | No Mental Health Disorder | P Valuea | OR (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |||

| Age, y | <.001 | |||||

| 6-11 | 2199 | 41.0 (38.3-43.7) | 12 287 | 52.0 (50.6-53.3) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 12-17 | 4220 | 59.0 (56.3-61.7) | 15 665 | 48.0 (46.7-49.4) | 1.65 (1.44-1.89) | |

| Male | 3670 | 59.7 (57.2-62.3) | 13 886 | 49.5 (48.2-50.9) | <.001 | 1.31 (1.14-1.49) |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||||

| Hispanic | 633 | 17.9 (15.3-20.6) | 3025 | 25.5 (24.0-27.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 4836 | 61.2 (58.4-64.0) | 19 574 | 50.9 (49.5-52.3) | 1.90 (1.51-2.39) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 353 | 13.0 (11.0-14.9) | 1665 | 13.1 (12.1-14.1) | 0.98 (0.74-1.31) | |

| Other | 597 | 7.9 (6.5-9.3) | 3688 | 10.5 (9.8-11.2) | 1.19 (0.88-1.60) | |

| Poverty status, % | .07 | |||||

| 0-199 | 1880 | 45.6 (43.0-48.3) | 6635 | 42.4 (41.0-43.9) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 200-399 | 1913 | 25.1 (22.9-27.2) | 8520 | 26.4 (25.3-27.5) | 1.19 (0.98-1.44) | |

| ≥400 | 2626 | 29.3 (27.2-31.3) | 12 797 | 31.1 (30.1-32.2) | 1.40 (1.16-1.70) | |

| Family | <.001 | |||||

| 2 Parents, married | 4062 | 56.4 (53.8-59.0) | 20 665 | 67.8 (66.5-69.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 2 Parents, unmarried | 435 | 8.7 (6.8-10.6) | 1582 | 7.5 (6.7-8.3) | 1.23 (0.91-1.65) | |

| Single mother or other | 1820 | 34.9 (32.5-37.4) | 5234 | 24.7 (23.5-25.9) | 1.40 (1.19-1.65) | |

| Insurance type | <.001 | |||||

| Any public | 2106 | 48.0 (45.3-50.6) | 5489 | 35.6 (34.1-37.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Private only | 4224 | 50.6 (47.9-53.2) | 21 981 | 62.4 (60.9-63.9) | 0.62 (0.51-0.75) | |

| Unspecified | 66 | 1.4 (0.9-2.0) | 366 | 2.0 (1.5-2.6) | 0.60 (0.37-0.99) | |

| No continuous insurance in the past 12 mo | 132 | 2.0 (1.4-2.5) | 458 | 2.6 (2.1-3.1) | .12 | 0.62 (0.38-1.00) |

| No medical homec | 3344 | 58.3 (55.9-60.8) | 11 850 | 49.9 (48.6-51.3) | <.001 | 1.31 (1.15-1.49) |

| Special health care needs | 4489 | 72.2 (69.8-74.6) | 5638 | 20.3 (19.2-21.3) | <.001 | 9.59 (8.37-10.99) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Estimates were compared using χ2 test.

Adjusted for all covariates.

Children were considered to not have a medical home if at least 1 of the following was true: did not have a personal doctor or nurse; did not have a usual place of care; received family-centered care; obtained specialty care referrals if needed; and obtained health care coordination if needed.

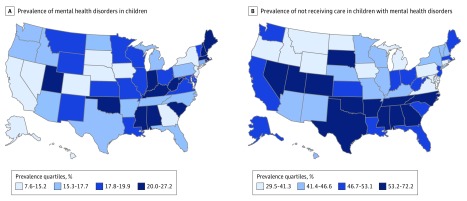

The national prevalence of children with a mental health disorder who did not receive needed treatment or counseling from a mental health professional was 49.4%, which ranged from 29.5% (Washington, DC) to 72.2% (North Carolina). After transforming state-level data into quartiles, Figure, A shows the prevalence of mental health disorders in children and Figure, B shows the prevalence of children with at least 1 mental health disorder who did not receive needed treatment or counseling from a mental health professional.

Figure. Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders and Mental Health Care Use Among US Youth.

A, State-level prevalence presented as quartiles of at least 1 mental health disorder (ie, depression, anxiety problems, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in the total sample of children (weighted estimate, 46.6 million). B, State-level prevalence presented as quartiles of children with a mental health disorder not receiving needed treatment or counseling from a mental health professional (weighted estimate, 7.7 million).

Discussion

The principal finding was that half of the estimated 7.7 million US children with a treatable mental health disorder did not receive needed treatment from a mental health professional. This estimate varied considerably by state. Of the 13 states that were in the top quartile for mental health disorder prevalence (Figure, A), Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah were also in the top quartile for the prevalence of children with a mental health disorder who did not receive needed treatment (Figure, B).

State-level practices and policies play a role in health care needs and use,6 which may help to explain the state variability observed in this study. Nevertheless, initiatives that assist systems of care coordination have demonstrated a reduction of mental health–related burdens across multiple domains.1 Policy efforts aimed at reducing burden and improving treatment across states are needed.

References

- 1.US Center for Mental Health Services The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program: evaluation findings: annual report to Congress, 2011. https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/pep13-cmhi2011.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2018.

- 2.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56-64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyu HH, Pinho C, Wagner JA, et al. ; Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration . Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(3):267-287. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, et al. ; Scientific Advisory Board and the Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental Health . Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475(7354):27-30. doi: 10.1038/475027a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. http://www.childhealthdata.org. Accessed August 1, 2018.

- 6.Black LI, Schiller JS. State variation in health care service utilization: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(245):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]