Key Points

Question

How well does a validated harm-reduction drinking measure perform as an efficacy outcome in alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy trials?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of 3 randomized clinical trials comprising 1169 participants, outcomes based on World Health Organization drinking risk levels, measured in grams of alcohol per day, were obtained. One- and 2-level reductions differentiated medication effects in a manner similar to US Food and Drug Administration–recognized outcomes of abstinence and no heavy drinking days but were achieved by more patients.

Meaning

Reductions in World Health Organization drinking risk level align with patients’ goals more strongly than abstinence, recognize more people as being successfully treated, and could encourage future medication development for undertreated alcohol use disorder.

Abstract

Importance

The US Food and Drug Administration recognizes total abstinence and no heavy drinking days as outcomes for pivotal pharmacotherapy trials for alcohol use disorder (AUD). Many patients have difficulty achieving these outcomes, which can discourage seeking treatment and has slowed the development of medications that affect alcohol use.

Objective

To compare 2 drinking-reduction outcomes with total abstinence and no heavy drinking outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data were obtained from 3 multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of medications for treating alcohol dependence (naltrexone, varenicline, and topiramate) in adults with DSM-IV–categorized alcohol dependence.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Within each trial, the percentage of participants in active and placebo conditions who met responder definitions of abstinence, no heavy drinking days, a WHO 1-level reduction, and a WHO 2-level reduction was computed by month with corresponding effect sizes (Cohen h).

Results

Across the 3 trials (N = 1169; mean [SD] age, 45 [10] years; 824 [70.5%] men), the percentage of participants classified as responders during the last 4 weeks of treatment was lowest for abstinence (naltrexone, 34.7% [100 of 288]; varenicline, 7.3% [7 of 96]; topiramate, 11.7% [21 of 179]) followed by no heavy drinking days (naltrexone, 51.0% [147 of 288]; varenicline, 24.0% [23 of 96]; topiramate, 20.7% [37 of 179]), WHO 2-level reduction (naltrexone, 75.0% [216 of 288]; varenicline, 55.2% [53 of 96]; topiramate, 44.7% [80 of 179]), and WHO 1-level reduction (naltrexone, 83.3% [240 of 288]; varenicline, 69.8 [67 of 96]; topiramate, 54.7% [98 of 179]) outcomes. Standardized treatment effects observed for the WHO 2-level reduction outcomes (naltrexone, Cohen h = 0.214 [95% CI, 0.053 -0.375]; varenicline, 0.273 [95% CI, −0.006 to 0.553]; topiramate, 0.230 [95% CI, 0.024-0.435]) and WHO 1-level reduction (naltrexone, Cohen h = 0.116 [95% CI, −0.046 to 0.277]; varenicline, 0.338 [95% CI, 0.058-0.617]; topiramate, 0.014 [95% CI, −0.192 to 0.219]) were comparable with those obtained using abstinence (naltrexone, Cohen h = 0.142 [95% CI, −0.020 to 0.303]; varenicline, 0.146 [95% CI, −0.133 to 0.426]; topiramate, 0.369 [95% CI, 0.163-0.574]) and no heavy drinking days (naltrexone, Cohen h = 0.140 [95% CI, −0.021 to 0.302]; varenicline, 0.232 [95% CI, −0.048 to 0.511]; topiramate, 0.207 [95% CI, 0.002-0.413]).

Conclusions and Relevance

WHO drinking risk level reductions appear to be worthwhile indicators of treatment outcome in AUD pharmacotherapy trials. These outcomes may align with drinking reduction goals of many patients and capture clinically meaningful improvements experienced by more patients than either abstinence or no heavy drinking days.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00006206; NCT01146613; NCT00210925

This secondary data analysis of data from clinical trials evaluates the sensitivity of World Health Organization risk level reduction of alcohol intake as outcomes in alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy trials.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a destructive chronic disease that causes medical, psychological, social, and economic problems and results in 88 000 deaths annually.1 Alcohol use disorder affects 13.9% of US adults (approximately 17 million), reflecting an increase of approximately 50% between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013.2 Despite this disease burden, less than 8% of adults with AUD receive treatment within a year,3 and of those, only about half receive evidenced-based pharmacotherapy.4,5 Of numerous barriers to treatment,6,7 the perception that abstinence is the only treatment goal may discourage treatment seeking.8,9 Moreover, the expectation that patients should be abstinent, coupled with the low rate of those who are able or willing to achieve abstinence, may reduce confidence in the effectiveness of treatment among patients and treatment professionals. This situation may also discourage pharmaceutical companies from developing new medications10; indeed, only 2 medications, naltrexone hydrochloride and acamprosate calcium, have been approved for AUD in the United States in more than 20 years.

Because reductions in drinking can be clinically meaningful, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now accepts both abstinence and no heavy drinking days as a primary outcome for phase 3 trials of AUD pharmacotherapy,11 in which a heavy drinking day is 4 or more (women) or 5 or more (men) drinks in a day. Both outcomes are well validated, as individuals who achieve either outcome have a lower risk of an AUD or other adverse consequences.11,12,13,14,15,16,17

Although both outcomes are clinically intuitive and interpretable, particularly compared with continuous outcomes that capture group mean alcohol consumption,14 neither considers the volume of alcohol consumed prior to treatment, so the magnitude of reduction is not factored into success or failure. Furthermore, neither outcome considers reductions in drinking short of abstinence or no heavy drinking days as potentially benefitting how a patient feels and functions.11 Yet, individuals who have some heavy drinking days mixed with lower-risk drinking days may feel and function as well as those who achieve abstinence or no heavy drinking days.14,18 Finally, the low success rate in achieving abstinence or no heavy drinking days could reduce optimism about treatment or create a mistaken impression that drinking reductions short of those outcomes have no benefit. An outcome that can be attained by more patients, while reflecting clinical benefit, would be desirable and overcome these problems.

Other responder definitions based on reductions in alcohol consumption have been proposed and, in some cases, accepted by regulatory agencies. For instance, as a key secondary outcome, the European Medicines Agency accepts the percentage of individuals who reduce their World Health Organization (WHO)19 risk level (expressed as grams of pure ethanol per day) by at least 2 levels from very high risk to medium risk or from high risk to low risk20 (Table 1). Data validating this approach are promising. Two recent studies showed that WHO 1- and WHO 2-level reductions in risk levels are associated with clinically meaningful benefits, including reduced risk of DSM-IV–categorized alcohol dependence (using epidemiologic data from a large prospective survey)21 and reductions in alcohol-related consequences and improvements in mental health symptoms (using data from a large AUD pharmacotherapy trial).22 However, to our knowledge, there is only 1 published study23 documenting whether the WHO risk-level reduction outcomes are sensitive to medication treatment effects in clinical trials. In that study, the WHO 2-level reduction outcome differentiated nalmefene hydrochloride from placebo in phase 3 trials of alcohol dependence in individuals with baseline WHO high or very high risk levels. Despite their potential for wider use, it is unknown how WHO risk reduction outcomes would perform in other AUD pharmacotherapy trials and whether they would compare favorably with the FDA-established definitions of abstinence or no heavy drinking days.

Table 1. World Health Organization (WHO) Risk Levels.

| Risk Level | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| Grams of pure ethanol per day | ||

| Abstinence | 0 | 0 |

| Low risk | 1-40 | 1-20 |

| Medium risk | 41-60 | 21-40 |

| High risk | 61-100 | 41-60 |

| Very high risk | ≥101 | ≥61 |

| Mean No. of standard drinks per daya | ||

| Abstinence | 0 | 0 |

| Low risk | >0-2.86 | >0-1.43 |

| Medium risk | 2.87-4.29 | 1.44-2.86 |

| High risk | 4.30-7.14 | 2.87-4.29 |

| Very high risk | ≥7.15 | ≥4.30 |

One standard drink, 14 g of pure ethanol.

To address these issues, we (the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative Workgroup10) conducted secondary data analyses of the WHO 1- and 2-level reduction outcomes to evaluate their sensitivity in distinguishing between active medication and placebo in 3 multisite AUD pharmacotherapy trials. Response rates and medication effect sizes for WHO risk reduction outcomes were compared with those for abstinence and no heavy drinking days.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data were obtained from 3 multisite, randomized, double-blind AUD pharmacotherapy trials in which the active medications were superior to placebo in reducing alcohol consumption: the COMBINE trial with emphasis on the naltrexone arms24 and trials of varenicline tartrate25 and topiramate.26 All 3 trials enrolled adults with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence according to the DSM-IV. All studies received approval by the study centers’ institutional review boards (from the University of Maryland for the topiramate trial and from the University of New Mexico for the varenicline trial), and study participants provided written informed consent. Details of each trial, including those required to complete a CONSORT checklist, were provided in the original publications and are summarized herein.

The naltrexone trial data are drawn from the COMBINE trial (N = 1383; 11 sites; January 2001-January 2004),24 a phase 3 trial that evaluated combinations of medications (acamprosate, naltrexone, or matched placebos) and behavioral interventions (medication management [MM] or combined behavioral intervention [CBI]) over 16 weeks. Per other analyses,12 we focused on the naltrexone arms without CBI (n = 607) because acamprosate was not superior to placebo and naltrexone showed efficacy only in increasing the number of abstinent days and reducing time to first heavy drinking day when given with MM without CBI. Participants were required to abstain from alcohol for at least 4 days prior to randomization.

The varenicline trial (N = 200; 5 sites; February 2011-February 2012)25 is a phase 2 trial that compared the efficacy of varenicline tartrate, 2 mg/d, with placebo in conjunction with computerized bibliotherapy. Medication was titrated over the first week during the 13-week trial. Participants could drink alcohol up to the time of randomization. Varenicline showed efficacy on 4 drinking outcomes, including reducing heavy and very heavy drinking days, drinks per day, and drinks per drinking day.

The topiramate trial (N = 371; 17 sites; January 2004-August 2006)26 is a phase 2 trial that compared the efficacy of oral topiramate, 300 mg/d, with placebo in conjunction with a brief behavioral intervention. Medication was titrated over 6 weeks during the 14-week treatment trial. Participants could drink alcohol up to the time of randomization. Topiramate showed efficacy on 3 drinking outcomes, including abstinent and heavy drinking days and drinks per drinking day.

Measures

WHO Risk Levels of Alcohol Consumption

All trials used the calendar-based timeline followback interview27 to capture retrospectively self-reported daily drinking, with the naltrexone and varenicline trials also using the Form 90.28 For the present analysis, the recorded number of US standard drinks consumed was converted to grams of pure ethanol.

WHO drinking risk levels (Table 1) were calculated based on mean grams of pure ethanol consumed per day (which includes zero for abstinent days). Although the original WHO risk levels19 did not specify abstinence as a separate risk level, we included it as a fifth level given the prominence of abstinence as a goal of alcohol treatment and an outcome in clinical trials.22 Pretreatment risk levels for each trial were calculated using data from the 28 days prior to screening. During treatment, the risk levels were also based on 28-day periods (months).

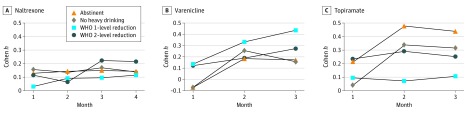

The WHO 1- and 2-level reduction outcomes were calculated and defined as the percentage of participants whose alcohol use decreased by at least 1 or 2 risk levels, respectively, from baseline to the last 4 weeks of treatment (Table 2) or each month of treatment (excluding weeks 13 and 13-14 in the varenicline and topiramate trials, respectively) (Figure; eFigures 1-4 and the eAppendix in the Supplement). For the 1-level reduction outcome, this percentage included participants who reduced from very high to high risk (or below), high to medium risk (or below), and medium to low risk (or below). For the WHO 2-level reduction outcome, this percentage included participants who reduced from very high to medium risk (or below), high to low risk (or below), and medium risk to abstinence.

Table 2. Treatment Effects for Traditional and WHO Risk Level Reduction Definitions of Response During the Last 4 Weeks of Treatmenta.

| Clinical Trial | Sample Sizeb | Responder Outcome | Placebo, No. (%) | Medication, No. (%) | h (95% CI)c,d | NNT (95 % CI)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone24,e | Placebo, 302; medication, 288 | Abstinent | 85 (28.1) | 100 (34.7) | 0.142 (−0.020 to 0.303) | 16 (111.9 [H] to ∞ to 7.1 [B]) |

| No heavy drinking days | 133 (44.0) | 147 (51.0) | 0.140 (−0.021 to 0.302) | 15 (96.2 [H] to ∞ to 6.6 [B]) | ||

| WHO 2-level reduction | 197 (65.2) | 216 (75.0) | 0.214 (0.053 to 0.375) | 11 (5.8 [B] to 41.4 [B]) | ||

| WHO 1-level reduction | 238 (78.8) | 240 (83.3) | 0.116 (−0.046 to 0.277) | 23 (55.7 [H] to ∞ to 9.2 [B]) | ||

| Varenicline25 | Placebo, 101; medication, 96 | Abstinent | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.3) | 0.146 (−0.133 to 0.426) | 30 (32.6 [H] to ∞ to 10.3 [B]) |

| No heavy drinking days | 15 (14.9) | 23 (24.0) | 0.232 (−0.048 to 0.511) | 11 (54.3 [H] to ∞ to 5.0 [B]) | ||

| WHO 2-level reduction | 42 (41.6) | 53 (55.2) | 0.273 (−0.006 to 0.553) | 8 (486.2 [H] to ∞ to 3.6 [B]) | ||

| WHO 1-level reduction | 54 (53.5) | 67 (69.8) | 0.338 (0.058 to 0.617) | 7 (3.4 [B] to 34.3 [B]) | ||

| Topiramate26 | Placebo, 185; medication, 179 | Abstinent | 5 (2.7) | 21 (11.7) | 0.369 (0.163 to 0.574) | 12 (7.0 [B] to 26.2 [B]) |

| No heavy drinking days | 24 (13.0) | 37 (20.7) | 0.207 (0.002 to 0.413) | 13 (6.5 [B] to 1581.1 [B]) | ||

| WHO 2-level reduction | 62 (33.5) | 80 (44.7) | 0.230 (0.024 to 0.435) | 9 (4.7 [B] to 81.8 [B]) | ||

| WHO 1-level reduction | 100 (54.1) | 98 (54.7) | 0.014 (−0.192 to 0.219) | 144 (10.5 [H] to ∞ to 9.2 [B]) |

Abbreviations: B, number needed to benefit; H, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat; WHO, World Health Organization.

Participants with any missing drinking data were imputed as nonresponders for all outcomes. Percentages are rounded; Cohen h NNT are rounded and are based on unrounded percentages. The WHO 1- and 2-level reduction outcomes represent the percentage of participants who reduced drinking by 1 or more and 2 or more WHO drinking risk levels, respectively.

Denominator for prevalence estimates.

Cohen h = φMedication – φPlacebo, where φ = 2arcsin(percentage)½ is a measure of effect size for dichotomous outcomes, with the interpretation: small, 0.20; medium, 0.50; and large, 0.80.

For Cohen h, 95% CIs that do not include zero are statistically significant (P < .05). For NNT, statistically significant estimates are indicated by 95% CIs with lower and upper bounds both expressed as number needed to benefit. Nonsignificant estimates are indicated by 95% CIs with a lower bound expressed as number needed to harm, indicating less efficacy in the medication than the placebo group, and an upper bound expressed as number needed to benefit; infinity is included in the 95% CI because NNT is infinity when the absolute risk reduction is 0.

Participants in the WHO low-risk drinking level at baseline (n = 17) were excluded.

Figure. Treatment Effects (Cohen h) for Responder Outcomes by Treatment Month.

Treatment effects in the naltrexone (A), varenicline (B), and topiramate (C) trials. In the varenicline trial, Cohen h = −0.401 for the month 1 abstinent outcome was truncated to −0.072 for graphic purposes. The negative Cohen h value was the result of a somewhat higher percentage of participants reporting abstinence in the placebo group than the varenicline group (4% vs 0%, respectively). In the varenicline and topiramate trials, estimates of Cohen h in month 3 do not match those in the last 4 weeks of treatment because they are using overlapping but somewhat different 28-day periods. In both trials, month 3 is study weeks 9 to 12; however, the last 4 weeks of treatment are study weeks 11 to 13 in the varenicline trial and study weeks 11 to 14 in the topiramate trial. WHO indicates World Health Organization.

Participants in the low-risk level at baseline were eliminated from analysis because, by definition, they could not attain the WHO 2-level reduction in risk level and are not typically enrolled in clinical trials. Seventeen of 607 participants (2.8%) in the naltrexone (COMBINE trial) analytic sample were excluded.

Abstinence and No Heavy Drinking Days

To make comparisons with other drinking reduction outcomes, abstinence and no heavy drinking days were computed for the same time periods. Abstinence was defined as no drinking during the month. No heavy drinking days was defined as never consuming 4 or more standard drinks (women) or 5 or more standard drinks (men) on any day during the month, with a standard drink containing 14 g of ethanol.

Statistical Analysis

To facilitate the comparison of treatment effects obtained using the various responder definitions, Cohen h for independent percentages and 95% CIs were computed29:

| Cohen h = φMedication – φPlacebo, |

where φ = 2arcsin[proportion]½.

For interpretation, the following categories of effect size can be applied: small, 0.20; medium, 0.50; and large, 0.80. The number needed to treat (NNT) to obtain each type of response and 95% CIs30 was also computed:

| NNT = 1/(Proportion Responding to Active Medication − Proportion Responding to Placebo). |

Outcomes were calculated with imputation such that participants with any missing data within a given 28-day period were considered nonresponders. We also performed a sensitivity analysis in which missing data were not imputed. Analyses were conducted using SAS, versions 9.2 and 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants in all 3 trials (N = 1169) were mainly middle-aged (mean [SD], 45 [10] years) white (77.7% [n = 908]) men (70.5% [n = 824]) (Table 3). Most participants consumed alcohol at the very high- or high-risk levels.

Table 3. Participant Characteristics by Clinical Trial.

| Characteristic | Naltrexone (n=607) | Varenicline (n=198) | Topiramate (n=364) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication (n=302) | Placebo (n=305) | Medication (n=97) | Placebo (n=101) | Medication (n=179) | Placebo (n=185) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 44.2 (10.4) | 43.9 (10.1) | 46.0 (11.0) | 45.0 (12.3) | 46.7 (9.4) | 47.8 (8.7) |

| Men, No. (%) | 211 (69.9) | 207 (67.9) | 71 (73.2) | 69 (68.3) | 133 (74.3) | 133 (71.9) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 227 (75.2) | 241 (79.0) | 60 (619) | 71 (70.3) | 152 (84.9) | 157 (84.9) |

| Black | 30 (9.9) | 21 (6.9) | 30 (30.9) | 27 (26.7) | 13 (7.3) | 17 (9.2) |

| Hispanic | 39 (12.9) | 34 (11.1) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.0) | 12 (6.7) | 7 (3.8) |

| Other | 6 (2.0) | 9 (3.0) | 5 (5.2) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.2) |

| Educational level (<high school), No. (%) | 94 (31.1) | 89 (29.2) | 37 (38.1) | 29 (28.7) | NA | NA |

| Alcohol consumption (baseline) | ||||||

| Abstinent, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No heavy drinking days, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Percent days abstinent, mean (SD) | 22.6 (21.8) | 21.3 (22.0) | 7.7 (12.5) | 7.9 (13.6) | 10.9 (16.0) | 9.7 (15.0) |

| Percent heavy drinking days, mean (SD) | 67.3 (27.2) | 68.5 (26.9) | 88.1 (15.8) | 87.2 (16.4) | 82.4 (19.6) | 83.8 (19.4) |

| Drinks per day, mean (SD) | 8.6 (6.2) | 8.4 (5.6) | 14.2 (9.3) | 12.5 (8.9) | 10.0 (4.4) | 9.6 (3.9) |

| Drinks per drinking day, mean (SD) | 11.2 (6.8) | 10.9 (6.7) | 15.3 (9.6) | 13.6 (9.0) | 11.4 (4.8) | 10.9 (4.3) |

| WHO risk level, No. (%) | ||||||

| Low | 14 (4.6) | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medium | 25 (8.3) | 25 (8.2) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| High | 58 (19.2) | 67 (22.0) | 23 (23.7) | 28 (27.7) | 58 (32.4) | 60 (32.4) |

| Very high | 205 (67.9) | 210 (68.9) | 74 (76.3) | 72 (71.3) | 119 (66.5) | 123 (66.5) |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; WHO, World Health Organization.

WHO Risk Level Reduction vs Traditional Outcomes at the Last 4 Weeks of Treatment

Responder Outcome Rates Across Studies

During the last 4 weeks of treatment, the percentage of responders in both the placebo and active medication groups in each trial increased from the most conservative outcome (abstinence) to the least conservative outcome (WHO 1-level reduction) (Table 2). For example, in the COMBINE trial, among the 288 participants receiving naltrexone, 34.7% (n = 100) achieved abstinence, 51.0% (n = 147) achieved no heavy drinking days, 75.0% (n = 216) achieved a WHO 2-level reduction, and 83.3% (n = 240) achieved a WHO 1-level reduction. The same ordering of outcomes was seen in the varenicline trial (n = 96, 7.3% [n = 7] achieved abstinence; 24.0% [n = 23] achieved no heavy drinking days; 55.2% [n = 53] achieved a WHO 2-level reduction; and 69.8% [n = 67] achieved a WHO 1-level reduction) and topiramate trial (n = 179, 11.7% [n = 21] achieved abstinence; 20.7% [n = 37] achieved no heavy drinking days; 44.7% [n = 80] achieved a WHO 2-level reduction; and 54.7% [n = 98] achieved a WHO 1-level reduction), although responder rates were lower overall in these trials, as the varenicline and topiramate trials required heavy drinking in the week prior to randomization, whereas pretreatment abstinence was required in the naltrexone study.

Effect Sizes by Study

During the last 4 weeks (weeks 13-16) of the COMBINE trial, the naltrexone treatment effect for the WHO 2-level reduction outcome (Cohen h = 0.214 [95% CI, 0.053 -0.375], NNT = 11 [95% CI, 5.8 (number needed to benefit [B]) to 41.4 (B)]) was modest but greater than for abstinence (Cohen h = 0.142 [95% CI, −0.020 to 0.303], NNT = 16 (95% CI, 111.9 [number needed to harm (H)] to ∞ to 7.1 [B]), no heavy drinking days (Cohen h = 0.140 [95% CI, −0.021 to 0.302], NNT = 15 (95% CI, 96.2 [H] to ∞ to 6.6 [B]), and the WHO 1-level reduction (Cohen h = 0.116 [95% CI, −0.046 to 0.277], NNT = 23 (95% CI, 55.7 [H] to ∞ to 9.2 [B]) (Table 2).

During the last 4 weeks (weeks 10-13) of the varenicline trial, the varenicline treatment effect for the WHO 1- level reduction outcomes (Cohen h = 0.338 [95% CI, 0.058-0.617]; NNT = 7 [95% CI, 3.4 (B) to 34.3 (B)]) and WHO 2-level reduction outcomes (Cohen h = 0.273 [95% CI, −0.006 to 0.553]; NNT = 8 [95% CI, 486.2 (H) to ∞ to 3.6 (B)]) was larger than for either abstinence (Cohen h = 0.146 [95% CI, −0.133 to 0.426]; NNT = 30 [95% CI, 32.6 (H) to ∞ to 10.3 (B)]) or no heavy drinking days (Cohen h = 0.232 [95% CI, −0.048 to 0.511]; NNT = 11 [95% CI, 54.3 (H) to ∞ to 5.0 (B)]). There was a slightly larger treatment effect for the WHO 1-level reduction outcome (Cohen h = 0.338 [95% CI, 0.058-0.617]) than the WHO 2-level reduction outcome (Cohen h = 0.338 [95% CI, 0.058-0.617]).

During the last 4 weeks (weeks 11-14) of the topiramate trial, the topiramate treatment effect for the WHO 2-level reduction outcome (Cohen h = 0.230 [95% CI, 0.024-0.435]) was comparable to that for no heavy drinking days (Cohen h = 0.207 [95% CI, 0.002-0.413]) but smaller than that for abstinence (Cohen h = 0.369 [95% CI, 0.163-0.574]). The treatment effect for the WHO 1-level reduction was the smallest of the outcomes (Cohen h = 0.014 [95% CI, −0.192 to 0.219]).

Treatment Effects and Response Rates by Month

For the WHO 2-level reduction outcome in the COMBINE trial, the naltrexone treatment effect was greater in months 3 and 4 (Cohen h = 0.223 and 0.214, respectively) than in months 1 and 2 (Cohen h = 0.114 and 0.066, respectively) (Figure, A). For the WHO 1-level reduction outcome, the naltrexone treatment effect increased from month 1 to 2 (Cohen h = 0.028 and 0.091, respectively) and remained stable thereafter. Treatment effects for abstinence (Cohen h: month 1 = 0.127; month 2 = 0.142; month 3 = 0.149; and month 4 = 0.142) and no heavy drinking days (Cohen h: month 1 = 0.155; month 2 = 0.135; month 3 = 0.169; and month 4 = 0.140) were stable across all months. Similar results were obtained when missing data were not imputed (eFigure 4A in the Supplement). Responder rates for all outcomes decreased over time (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

For all outcomes, the varenicline treatment effect was smallest at month 1 and larger thereafter (Figure, B). Treatment effects for both WHO level reduction outcomes increased monotonically by month, although increases were larger for the 1-level reduction (Cohen h: month 1 = 0.134; month 2 = 0.332; and month 3 = 0.434) than the WHO 2-level reduction (Cohen h: month 1 = 0.122; month 2 = 0.188; and month 3 = 0.272). For abstinence and no heavy drinking days, negative effect sizes that were observed during month 1 increased and remained stable during months 2 and 3 (Cohen h, abstinence: month 2 = 0.185; month 3 = 0.174; no heavy drinking days: month 2 = 0.255; month 3 = 0.157). Similar results were obtained when missing data were not imputed (eFigure 4B in the Supplement). Responder rates for all outcomes increased over time (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

For both WHO level reduction outcomes in the topiramate trial, the treatment effect was stable across months yet was consistently larger for the WHO 2-level (Cohen h = 0.235-0.290) than the 1-level reduction outcome (Cohen h = 0.071-0.105) (Figure, C). For both abstinence and no heavy drinking days, the treatment effect increased substantially from month 1 to 2 (abstinence, Cohen h = 0.212 and 0.477; no heavy drinking days, Cohen h = 0.041 and 0.337) and remained stable thereafter. Treatment effects for all responder outcomes increased when no imputation was performed for missing data (eFigure 4C in the Supplement), likely due to differential dropout from the active treatment condition (eg, in month 3, 29.6% [n = 53] vs 12.4% [n = 23] of participants in the topiramate and placebo groups were missing all drinking data). Responder rates for all outcomes increased over time (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of 3 large, multisite AUD pharmacotherapy trials, we evaluated the performance of the WHO 1- and 2-level reductions in risk levels of alcohol consumption, which are 2 proposed alcohol treatment outcome measures. Across the trials, the size of the treatment effects and NNT for these outcomes were as sensitive as or more sensitive than outcomes currently accepted by the FDA (abstinence or no heavy drinking days). Moreover, these proposed outcomes are consistent with the preferences of many patients for a reduced drinking goal.

For proposed outcomes to be accepted and adopted, they must meet the demands of key stakeholders; the WHO level reduction outcomes are well along this path. First, when dealing with surrogate measures of health (eg, alcohol consumption), regulatory agencies require that the clinical utility of the measures be validated against other health outcomes, as has been done in 2 prior studies of the WHO reduction outcomes.21,22 Second, researchers and pharmaceutical companies will require that the outcomes be at least as sensitive to the effects of medication as existing outcomes, which we demonstrated here. Third, although abstinence or no heavy drinking days may be an optimal goal for some, many patients would prefer to reduce their drinking, and thus the WHO level reductions, which are associated with meaningful improvements in function,19 are consistent with such a preference. Furthermore, more patients achieved improvements in WHO risk levels than abstinence or no heavy drinking days. Across trials, the percentage of participants in the active condition achieving each measure of success during the last 4 weeks of treatment was lowest for abstinence, followed by no heavy drinking days, the WHO 2-level reduction, and WHO 1-level reduction outcomes. More patients and treatment professionals may be willing to consider pharmacotherapy and support if they are provided with information that, in prior studies (eg, of varenicline), 54.7% of participants experienced a clinically meaningful reduction in drinking (WHO-2 shift) vs only 7.3% who achieved abstinence.

For evaluating the efficacy of medications for AUD, the WHO 2-level reduction may have advantages over the 1-level reduction. Specifically, the 2-level reduction produced larger effect sizes in 2 of 3 trials and less variable and lower NNTs across studies (8-11 vs 7-144). In addition, this more conservative outcome correlated with greater clinical benefit, such as lower risk for AUD, in prior epidemiologic and clinical studies.21,22 Nonetheless, the 1-level reduction outcome produced the largest treatment effects in the varenicline trial, is associated with clinical benefit,21,22 and could thus be valuable in trials in which the goal is to reduce drinking by a moderate amount in many patients.

The present study also explored whether treatment effects and response rates differed by month. As with the results for abstinence and no heavy drinking days, the first month generally produced the smallest treatment effects for the WHO reduction outcomes, with subsequent increases in effect size in all trials. Because participants in these trials, and generally individuals with AUD, typically have a long history of habitual heavy drinking, treatment professionals and patients may reasonably expect that maximal drinking reductions may take 1 or more months to emerge, even with efficacious treatments. While we examined the end points at each month, for phase 3 trial submissions to the FDA, these outcomes may need to be evaluated over a longer period.

Sensitivity analyses in which missing data were imputed as nonresponse yielded findings that varied little from those based on available data for the naltrexone and varenicline studies. In contrast, imputation resulted in substantial decreases in treatment effects in the topiramate study (eFigures 1-3 in the Supplement). Thus, the WHO level reduction outcomes, like other alcohol treatment outcomes,31 are sensitive to conservative imputation schemes, such as the one used in the present study, particularly when there is substantial differential dropout between treatment arms.

Limitations

This study has limitations. All drinking outcomes were based on participants’ retrospective self-report. Although such reporting is standard practice in clinical trials, it is subject to recall and social desirability bias. In addition, the WHO drinking risk levels could be improved for clinical practice by rounding standard drinks to whole numbers.

Conclusions

End points based on reductions in WHO drinking risk levels, measured in grams of pure ethanol per day, were obtained from 3 large, multisite AUD pharmacotherapy trials; reductions of 1 and 2 levels differentiated medication effects similarly to more traditional outcomes of abstinence and no heavy drinking days. When considered together with a growing body of clinical validation studies, the WHO level reduction outcomes are promising and could join abstinence and no heavy drinking days as primary outcomes for phase 3 clinical trials. The use of the same outcome by regulatory agencies in the United States and Europe, where a 2-level reduction is accepted, would harmonize regulatory requirements and provide efficiency in medication development for this undertreated disorder. In addition, the WHO level reduction measures capture reductions in drinking, the preferred goal of most patients, which are more often achieved than abstinence or no heavy drinking days. Substantial reductions in drinking, if agreed on as suitable goals of alcohol treatment, could increase the desirability and acceptability of treatment to patients and caregivers and enhance the drug development process by providing additional outcomes for clinical trials.

eAppendix. FDA Timing

eFigure 1. Naltrexone Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 2. Varenicline Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 3. Topiramate Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 4. Treatment effects (Cohen’s h) for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month (Not Imputed)

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Alcohol and public health: alcohol-related disease impact application (ARDI): 2013. http://nccd.cdc.gov/DPH_ARDI/default/default.aspx. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- 2.Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark TL, Kassed CA, Vandivort-Warren R, Levit KR, Kranzler HR. Alcohol and opioid dependence medications: prescription trends, overall and by physician specialty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):345-349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litten RZ, Falk DE, Ryan ML, Fertig JB. Discovery, development, and adoption of medications to treat alcohol use disorder: goals for the phases of medications development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1368-1379. doi: 10.1111/acer.13093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2-3):214-221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponce Martinez C, Vakkalanka P, Ait-Daoud N. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders: physicians’ perceptions and practices. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:182. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chartier KG, Miller K, Harris TR, Caetano R. A 10-year study of factors associated with alcohol treatment use and non-use in a US population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:205-211. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallhed Finn S, Bakshi AS, Andréasson S. Alcohol consumption, dependence, and treatment barriers: perceptions among nontreatment seekers with alcohol dependence. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(6):762-769. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.891616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anton RF, Litten RZ, Falk DE, et al. The Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE): purpose and goals for assessing important and salient issues for medications development in alcohol use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(2):402-411. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration Alcoholism: developing drugs for treatment guidance for industry: draft guidance. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM433618.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed May 2, 2018.

- 12.Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a 3-year follow-up. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(12):2036-2045. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delucchi KL, Weisner C. Transitioning into and out of problem drinking across seven years. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(2):210-218. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, et al. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(12):2022-2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Parthasarathy S, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mertens JR. Five-year healthcare utilization and costs among lower-risk drinkers following alcohol treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(2):579-586. doi: 10.1111/acer.12273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Craig M, Wilkinson DA, Davila R. Empirically based guidelines for moderate drinking: 1-year results from three studies with problem drinkers. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(6):823-828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.6.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Pearson MR, et al. How much is too much? patterns of drinking during alcohol treatment and associations with post-treatment outcomes across three alcohol clinical trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(1):59-69. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldridge AP, Zarkin GA, Dowd WN, Bray JW. The relationship between end-of-treatment alcohol use and subsequent healthcare costs: do heavy drinking days predict higher healthcare costs? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(5):1122-1128. doi: 10.1111/acer.13054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66529. Published 2000. Accessed May 2, 2018.

- 20.European Medicines Agency Guideline on the development of medicinal products for the treatment of alcohol dependence. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/03/WC500074898.pdf. Published February 10, 2010. Accessed May 2, 2018.

- 21.Hasin DS, Wall M, Witkiewitz K, et al. ; Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE) Workgroup . Change in non-abstinent WHO drinking risk levels and alcohol dependence: a 3 year follow-up study in the US general population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):469-476. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30130-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witkiewitz K, Hallgren KA, Kranzler HR, et al. Clinical validation of reduced alcohol consumption after treatment for alcohol dependence using the World Health Organization risk drinking levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(1):179-186. doi: 10.1111/acer.13272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aubin HJ, Reimer J, Nutt DJ, et al. Clinical relevance of as-needed treatment with nalmefene in alcohol-dependent patients. Eur Addict Res. 2015;21(3):160-168. doi: 10.1159/000371547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. ; COMBINE Study Research Group . Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, et al. ; NCIG (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Clinical Investigations Group) Study Group . A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):277-286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829623f4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. ; Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board; Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group . Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1641-1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: a technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, eds. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992:41-72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller WR. Form 90: A Structured Assessment Interview for Drinking and Related Behaviors: Test Manual. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1996. doi: 10.1037/e563242012-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155-159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1309-1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallgren KA, Witkiewitz K, Kranzler HR, et al. ; in conjunction with the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE) Workgroup . Missing data in alcohol clinical trials with binary outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1548-1557. doi: 10.1111/acer.13106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. FDA Timing

eFigure 1. Naltrexone Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 2. Varenicline Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 3. Topiramate Trial: Response Rates for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month

eFigure 4. Treatment effects (Cohen’s h) for Responder Endpoints by Treatment Month (Not Imputed)