Key Points

Question

Is maternal use of prenatal vitamins associated with decreased risk for autism recurrence in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder?

Findings

In this cohort study of 241 younger siblings of children with autism, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder was 14.1% in children whose mothers took prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy compared with 32.7% in children whose mothers did not take prenatal vitamins during that time.

Meaning

Maternal daily intake of prenatal vitamins during the first month of pregnancy appears to be associated with reductions in recurrence of autism in high-risk families; additional research is needed to confirm these results, to further investigate specific nutrients, and to inform public health recommendations for autism spectrum disorder prevention.

Abstract

Importance

Maternal use of folic acid supplements has been inconsistently associated with reduced risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the child. No study to date has examined this association in the context of ASD recurrence in high-risk families.

Objective

To examine the association between maternal prenatal vitamin use and ASD recurrence risk in younger siblings of children with ASD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study analyzed data from a sample of children (n = 332) and their mothers (n = 305) enrolled in the MARBLES (Markers of Autism Risk in Babies: Learning Early Signs) study. Participants in the MARBLES study were recruited at the MIND Institute of the University of California, Davis and were primarily from families receiving services for children with ASD in the California Department of Developmental Services. In this sample, the younger siblings at high risk for ASD were born between December 1, 2006, and June 30, 2015, and completed a final clinical assessment within 6 months of their third birthday. Prenatal vitamin use during pregnancy was reported by mothers during telephone interviews. Data analysis for this study was conducted from January 1, 2017, to December 3, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Autism spectrum disorder, other nontypical development (non-TD), and typical development (TD) were algorithmically defined according to Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and Mullen Scales of Early Learning subscale scores.

Results

After exclusions, the final sample comprised 241 younger siblings, of which 140 (58.1%) were male and 101 (41.9%) were female, with a mean (SD) age of 36.5 (1.6) months. Most mothers (231 [95.9%]) reported taking prenatal vitamins during pregnancy, but only 87 mothers (36.1%) met the recommendations to take prenatal vitamins in the 6 months before pregnancy. The prevalence of ASD was 14.1% (18) in children whose mothers took prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy compared with 32.7% (37) in children whose mothers did not take prenatal vitamins during that time. Children whose mothers reported taking prenatal vitamins during the first month of pregnancy were less likely to receive an ASD diagnosis (adjusted relative risk [RR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.30-0.81) but not a non-TD 36-month outcome (adjusted RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.75-1.75) compared with children whose mothers reported not taking prenatal vitamins. Children in the former maternal prenatal vitamin group also had statistically significantly lower autism symptom severity (adjusted estimated difference, –0.60; 95% CI, –0.97 to –0.23) and higher cognitive scores (adjusted estimated difference, 7.1; 95% CI, 1.2-13.1).

Conclusions and Relevance

Maternal prenatal vitamin intake during the first month of pregnancy may reduce ASD recurrence in siblings of children with ASD in high-risk families. Additional research is needed to confirm these results; to investigate dose thresholds, contributing nutrients, and biologic mechanisms of prenatal vitamins; and to inform public health recommendations for ASD prevention in affected families.

This cohort study examines the association between prenatal vitamin use in the early stages of pregnancy and the risk of autism in young children born into families who are genetically susceptible to autism spectrum disorder.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a growing concern, with 1 in every 59 children affected in the United States.1 Complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors likely contribute to ASD risk.2,3,4 Evidence is accumulating that the in utero environment,3,5,6 including gestational nutrition,6,7,8,9 has a potentially large role in the pathologic development of autism. A previous study found that maternal prenatal vitamin intake near conception was associated with an approximately 40% reduction in the risk of ASD in a population-based case-control study.7 This association was replicated in a prospective birth cohort study of 85 176 Norwegian children.9 Additional population-based cohort or nested case-control studies10,11,12,13 found that multivitamin or folic acid supplement intake was associated with reductions in the risk for ASD or autistic traits, but for some studies the association was not limited to use near conception,10,14 and another study showed no association.15

A limitation of these previous studies is the potential for confounding by mothers who are more healthy in many ways and thus more likely to follow guidelines to take prenatal vitamins at the start of pregnancy. This study limitation could be overcome by conducting a randomized clinical trial of folic acid prevention; however, given that ASD is still relatively uncommon and randomizing to placebo is unethical, the comparison of higher folic acid dose with the recommended dose would require a large sample size. Furthermore, the critical period for intervention might begin before pregnancy; thus, for a reliable diagnosis, a large number of women would need to be enrolled, and the subset who became pregnant would need to be followed until their child is 3 years of age, which would be expensive. Examining prenatal vitamin use within families already affected by autism could partially overcome this limitation by focusing on mothers already at high risk for having another child with ASD; the younger sibling shares environmental, genetic, and demographic factors with the affected older sibling. To our knowledge, no study to date has examined maternal prenatal vitamin use in the context of ASD recurrence in families affected by ASD.

This study examined whether maternal prenatal vitamin use is associated with reduced risk for ASD in high-risk younger siblings of children who have ASD. Siblings of children with ASD are approximately 12 times more likely to develop ASD than the general population, with a recurrence rate of nearly 1 in 5 siblings (19%-24%).16 They are also at higher risk for other behavioral or developmental diagnoses, including language delay, attention deficit, intellectual disability, and broader autism phenotype.17 These higher risks are attributed to shared genetic and environmental factors. This study focused on participants at high risk for developing ASD and other neurodevelopmental outcomes. With this prospective design, we could more efficiently assess prenatal vitamin use as a potentially protective factor while controlling for a wide range of family characteristics.

Methods

Study Population and Design

Children in this study were enrolled from MARBLES (Markers of Autism Risk in Babies: Learning Early Signs), a study that recruits children from families who receive services through the California Department of Developmental Services16 and that contacts Northern California mothers who have a child with confirmed ASD and who are either planning a pregnancy or pregnant with another child. Participants were recruited at the MIND Institute of the University of California, Davis. The MARBLES team prospectively collected demographic, lifestyle, environmental, and medical information (including supplementation habits) through telephone-assisted interviews and mailed questionnaires. Infants received standardized neurodevelopmental assessments beginning at 6 months and concluding at 3 years of age. The study sample was derived from younger siblings (n = 332) who were born between December 1, 2006, and June 30, 2015, and completed a final clinical assessment within 6 months of their third birthday. The University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board and the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study and the MARBLES study protocols. Neither data nor specimens were collected from children until written informed consent was obtained from their parents. Data analysis for this study was conducted from January 1, 2017, to December 3, 2018.

Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Use

Vitamin and supplement information, including brand, frequency, dose, and timing of maternal intake, for the 6 months before and each month during the pregnancy of the younger sibling was obtained through telephone interviews conducted for the first and second halves of pregnancy and again after birth. The interviews included questions about supplement intake throughout the pregnancy since the previous interview (eMethods in the Supplement). Information from multiple questionnaires was merged to determine prenatal vitamin use for each month before and during the pregnancy.

Positive responses to vitamin use and maximum frequency or dose were recorded for months that overlapped across the questionnaires. Self-reported brand names for vitamins and supplements were used to confirm or correctly classify prenatal vitamins. Adjustments in the denominator for each of the later months were made to account for shorter gestational ages at the time of birth; premature pregnancies were excluded from calculations for the months the mother was not pregnant. Total mean daily folic acid and iron intake from supplements was calculated according to the brands, frequencies, and doses reported for the first month of pregnancy. Categories of mean maternal folic acid and iron intake were based on tertiles of intake for the entire study population and on compliance with the Institute of Medicine–recommended dietary reference intakes for pregnancy of 600 μg folic acid18 and 27 mg iron.19

Outcome Measures and Classification

Trained, reliable examiners assessed the children’s development, including conducting diagnostic assessments for ASD at 3 years using the criterion standard Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), a semistructured, standardized assessment tool in which the examiner observes the child’s social interaction, communication, play, and imaginative use of materials.20,21 The ADOS module 2 algorithm score range is 0 to 28, with higher total scores (7 or higher) indicating evidence for ASD. Cognitive function was measured with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL),22 which generates 4 subscale scores (fine motor, expressive language, receptive language, and visual reception) and an overall early learning composite score. The MSEL composite score range is 49 to 155, and the T-score range is 20 to 80, with lower composite scores (below 70) indicating developmental delays in cognitive functioning.

Participants were classified into 1 of 3 outcome groups (ASD, typical development [TD], or nontypical development [non-TD]) according to an algorithm that uses ADOS and MSEL scores.17,23,24 Children in the ASD outcome group had scores that were higher than the ADOS cutoff scores and met the DSM-5 criteria for ASD. Children in the non-TD group had low MSEL scores (ie, 2 or more MSEL subscale scores more than 1.5 SD below the normative mean or at least 1 MSEL subscale score more than 2 SD below the normative mean), elevated ADOS scores (ie, within 3 points of the ASD cutoff scores), or both. Children in the TD outcome group had all MSEL scores within 2.0 SD and no more than 1 MSEL subscale score that was 1.5 SD below the normative mean, and their ADOS scores were at least 3 or more points below the ASD cutoff scores. Standardized ADOS-calibrated severity scores (known as comparison scores in the ADOS-2 scale) were calculated as indicators of ASD symptom severity on the ADOS scale depending on age and language level.25 The ADOS-2 comparison scores range from 1 to 10, with a score of 3 or higher indicative of ASD and 6 or higher indicating severe symptoms.26

Statistical Analysis

We calculated P values for group comparisons using 2-sided χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and independent 2-tailed t tests or 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. We used multinomial logistic regression to examine the association between prenatal vitamin use and diagnosis of ASD or non-TD outcome compared with TD. The following variables were examined as potential upstream confounders: maternal age, educational level, prepregnancy body mass index, birthplace (eg, United States or other country), and pregnancy intent; paternal age; child sex, year of birth, and race/ethnicity; home ownership; and type of payment for the delivery. Bivariate analyses examined unadjusted associations of potential confounders with both outcomes (ASD and non-TD) and vitamin use. Next, we built multivariable models, separate for ASD and non-TD risk, by adding 1 variable at a time to the multinomial logistic model and retaining only those variables that caused a 10% or larger change in the exposure or the odds ratio estimates. After the final models were selected, we calculated ASD and non-TD multivariable-adjusted relative risks (RRs) directly using a SAS macro, %RELRISK8 (SAS Institute Inc).27 Stratified analyses and corresponding RRs (when numbers allowed) were used to examine effect modification of prenatal vitamin use by child sex, race (white or non-white), ethnicity (non-Hispanic or Hispanic), intellectual disability (defined as an MSEL composite score under 70 points), and advanced maternal age (≥35 years or <35 years).

A generalized linear model framework with standard choices for link functions, according to the type of outcome, was used to examine ADOS and MSEL scores. The MSEL composite scores were analyzed with normality assumption and a linear link. The distribution of the ADOS severity scores was skewed, with many children scoring at the minimum. Thus, ADOS scores were rescaled (by subtracting 1, the lowest score) and analyzed using negative binomial distribution with a log link.

We conducted additional univariable and multivariable nominal logistic regression analyses to find the association between maternal intake of folic acid and iron (categorized into tertiles and dichotomized according to the dietary reference intake for pregnancy) and outcome. We performed sensitivity analyses with targeted maximum likelihood estimation (TMLE)28 to allow for the possibility that the effect of the exposure may vary across the levels of confounders. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Primary analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and TMLE analyses were implemented with the tmle package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Of the 332 eligible younger siblings born to 305 mothers in the MARBLES study, 281 (84.6%) completed a final clinical visit and 272 (81.9%) received an algorithmic outcome classification within 6 months of their third birthday. We excluded from analysis 4 children because their outcome assessment was received after they were 42 months of age, 3 children because they had incomplete MSEL scores, and 2 children because their algorithm diagnosis data were received after analyses were conducted. Furthermore, we excluded 9 participants because they were missing prenatal vitamin data and 22 children because they were younger siblings of other children in the sample.

Of the 241 MARBLES siblings retained in the final sample, 140 (58.1%) were male and 101 (41.9%) were female, with a mean (SD) age of 36.5 (1.6) months. Fifty-five children (22.8%) met the algorithmic criteria for ASD, 60 (24.9%) had algorithmic outcomes of non-TD, and 126 (52.3%) were confirmed with TD. Children in the ASD group were statistically significantly more likely to be male compared with children in the TD group (38 of 55 [69.1%] vs 65 of 126 [51.6%]; P = .03). Mothers of children with ASD and non-TD compared with mothers of children with TD were less likely to have private insurance (39 of 55 [70.9%] and 41 of 59 [69.5%] vs 104 of 124 [83.9%]) and education of a bachelor’s degree or higher (21 [38.2%] and 27 [45.0%] vs 72 [57.1%]) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Children and Their Mothers in the MARBLES Study.

| Variable | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child 36-mo Outcome Classification | Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Use in First Month of Pregnancy | ||||||

| ASD (n = 55) | Non-TD (n = 60) | TD (n = 126) | P Value | Yes (n = 128) | No (n = 113) | P Value | |

| 36-mo Outcome classification | |||||||

| ASD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 18 (14.1) | 37 (32.7) | .003 |

| Non-TD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 35 (27.3) | 25 (22.1) | |

| TD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 75 (58.6) | 51 (45.1) | |

| Child | |||||||

| Male sex | 38 (69.1) | 37 (61.7) | 65 (51.6) | .07 | 73 (57.0) | 67 (59.3) | .72 |

| White race | 36 (65.5) | 34 (56.7) | 89 (70.6) | .17 | 87 (68.0) | 72 (63.7) | .49 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 21 (38.2) | 19 (31.7) | 37 (29.4) | .50 | 37 (28.9) | 40 (35.4) | .28 |

| Maternal age, mean (SD), y | 34.3 (5.4) | 34.6 (4.2) | 33.7 (4.9) | .49 | 34.2 (4.7) | 34.0 (5.1) | .80 |

| Paternal age, mean (SD), ya | 37.7 (6.0) | 36.8 (4.9) | 36.2 (6.3) | .27 | 36.5 (5.8) | 36.9 (6.1) | .61 |

| Maternal prepregnancy BMI | |||||||

| Normal | 23 (41.8) | 29 (48.3) | 64 (50.8) | .69 | 62 (48.4) | 54 (47.8) | .99 |

| Overweight | 17 (30.9) | 14 (23.3) | 35 (27.8) | 35 (27.3) | 31 (27.4) | ||

| Obese | 15 (27.3) | 17 (28.3) | 27 (21.4) | 31 (24.2) | 28 (24.8) | ||

| Maternal birthplace outside United States | 11 (20.0) | 17 (28.3) | 20 (15.9) | .14 | 26 (20.3) | 22 (19.5) | .87 |

| Maternal cigarette smoking before pregnancyb | 3 (5.6) | 7 (11.7) | 5 (4.0) | .13 | 6 (4.7) | 9 (8.0) | .30 |

| Insurance type at deliveryc | |||||||

| Private | 39 (70.9) | 41 (69.5) | 104 (83.9) | .04 | 109 (85.8) | 75 (67.6) | <.001 |

| Public | 16 (29.1) | 18 (30.5) | 20 (16.1) | 18 (14.2) | 36 (32.4) | ||

| Home ownershipb | 27 (50.0) | 37 (61.7) | 79 (62.7) | .26 | 88 (68.8) | 55 (49.1) | .002 |

| Maternal education | |||||||

| Less than a bachelor’s degree | 34 (61.8) | 33 (55.0) | 54 (42.9) | .04 | 52 (40.6) | 69 (61.1) | .002 |

| Bachelor’s, master’s, professional, or doctoral degree | 21 (38.2) | 27 (45.0) | 72 (57.1) | 76 (59.4) | 44 (38.9) | ||

| Maternal intention to become pregnant | |||||||

| Wanted to get pregnant | 32 (58.2) | 36 (60.0) | 83 (65.9) | .57 | 101 (78.9) | 50 (44.2) | <.001 |

| Wanted to wait until later | 6 (10.9) | 10 (16.7) | 13 (10.3) | 13 (10.2) | 16 (14.2) | ||

| Did not want to get pregnant | 7 (12.7) | 9 (15.0) | 13 (10.3) | 6 (4.7) | 23 (20.4) | ||

| No preference | 10 (18.2) | 5 (8.3) | 17 (13.5) | 8 (6.3) | 24 (21.2) | ||

| Maternal use of multivitamins in month before pregnancy | 14 (25.5) | 7 (11.7) | 17 (13.5) | .08 | 11 (8.6) | 27 (23.9) | .001 |

| Maternal use of multivitamins in first month of pregnancy | 12 (21.8) | 4 (6.7) | 17 (13.5) | .06 | 7 (5.5) | 26 (23.0) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MARBLES, Markers of Autism Risk in Babies: Learning Early Signs; NA, not applicable; non-TD, nontypical development; TD, typical development.

Frequency data missing for 2 children in ASD group, 1 in non-TD, 1 in TD, 1 in vitamin-taking, and 3 in non–vitamin-taking.

Frequency data missing for 1 child in ASD group and 1 in non–vitamin-taking.

Frequency data missing for 1 child in non-TD group, 2 in TD, 1 in vitamin-taking, and 2 in non–vitamin-taking.

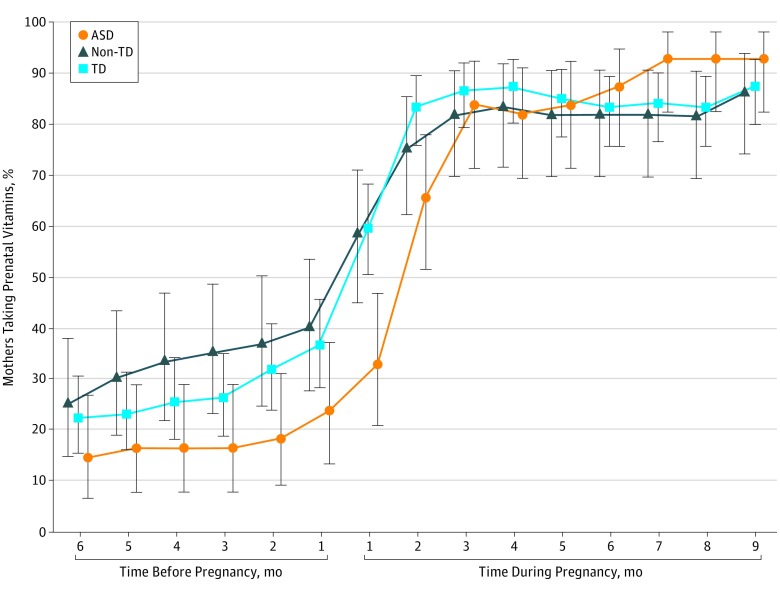

Most mothers (231 [95.9%]) reported taking prenatal vitamins at some point during pregnancy, but most (154 [63.9%]) did not comply with the recommendation to start taking prenatal vitamins in the 6 months before pregnancy; only 87 mothers (36.1%) met the recommendations (Figure). Mothers who took prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy (n = 128) compared with those who did not do so (n = 113) were more educated (76 [59.4%] vs 44 [38.9%]; P = .002), more likely to own their homes (88 [68.8%] vs 55 [49.1%]; P = .002), more likely to have private health insurance (109 [85.8%] vs 75 [67.6%]; P < .001), and more likely to have had an intentional pregnancy (101 [78.9%] vs 50 [44.2%]; P < .001) (Table 1). The prevalence of ASD was 14.1% (18) in children whose mothers took prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy compared with 32.7% (37) in children whose mothers did not take prenatal vitamins during that time.

Figure. Proportion of Mothers Who Reported Prenatal Vitamin Supplement Intake From 6 Months Before Pregnancy Through the End of Pregnancy.

ASD indicates autism spectrum disorder; non-TD, nontypical development; and TD, typical development. Vertical bars represent 95% exact CIs (Clopper-Pearson).

After statistical adjustment for confounders, we included the following in the final multivariable models: maternal education for ASD risk and child ethnicity, maternal age and education, maternal intention to become pregnant, and type of insurance for non-TD risk. After adjusting for maternal education, we found that children whose mothers took prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy were half as likely to receive an ASD diagnosis (adjusted RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.30-0.81) (Table 2 and eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement) but not a non-TD 36-month outcome (adjusted RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.75-1.75), and they had statistically significantly lower autism symptom severity (adjusted estimated difference, –0.60; 95% CI, –0.97 to –0.23) than children whose mothers did not take prenatal vitamins in the first month. No association was found between prenatal vitamin use and non-TD compared with TD (Table 2). A statistically significant RR for ASD was associated with prenatal vitamin use during the first month when compared with children with non-TD before (RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37-0.87; P = .01) and after (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.33-0.81; P = .004) adjusting for maternal education, age, type of insurance, and pregnancy intention and child white race. The difference in cognitive score across prenatal vitamin intake was statistically significant but was attenuated after adjustment (estimated difference, 7.1; 95% CI, 1.2-13.1) (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses using a TMLE framework confirmed these results (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Use in the First Month of Pregnancy With Child 36-Month and Outcome Assessment Scores.

| Outcome | Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Use in First Month of Pregnancy, No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 128) | No (n = 113) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| 36-mo Outcome classification | ||||

| ASD | 18 (14.1) | 37 (32.7) | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.75) | 0.50 (0.30 to 0.81)a |

| Non-TD | 35 (27.3) | 25 (22.1) | 0.97 (0.63 to 1.47) | 1.14 (0.75 to 1.75)a,b |

| TD | 75 (58.6) | 51 (45.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ADOS comparison score, median (IQR) | 1.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (5.0) | −0.60 (−0.97 to −0.23) | −0.56 (−0.94 to −0.18)c,d |

| MSEL composite score, mean (SD)f | 104.0 (21.0) | 94.2 (21.2) | 9.8 (4.3 to 15.2) | 7.1 (1.2 to 13.1)e,g |

Abbreviations: ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; IQR, interquartile range; MSEL, Mullen Scales of Early Learning; non-TD, nontypical development; RR, relative risk; TD, typical development.

Adjusted for maternal education in the ASD model and for child white or non-white race, maternal age and education, insurance delivery type, and maternal intention to become pregnant (yes or no) in the non-TD model.

Missing data for 3 children for the covariates in this model. The unadjusted model restricted to the same sample yielded 0.99 (95% CI, 0.65-1.52).

Represents the estimated difference (95% CI) in scores on the log scale from negative binomial regression models fitted to rescaled data between children whose mother reported taking prenatal vitamins and children whose mother reported not taking prenatal vitamins during the first month of pregnancy.

Adjusted for maternal education.

Represents the estimated difference (95% CI) in scores from linear regression models between children whose mother reported taking prenatal vitamins and children whose mother reported not taking prenatal vitamins during the first month of pregnancy.

Frequency data missing for 6 children in the vitamin-taking group and 4 in the non–vitamin-taking group.

Adjusted for child white or non-white race, maternal age and education, insurance delivery type, and intention to become pregnant (yes or no). In the adjusted model, 13 children were excluded because of missing outcome or covariates.

The effect estimates for the associations between prenatal vitamin use in the first month of pregnancy and reduced ASD risk did not differ substantially by child race or ethnicity or by maternal age but did differ across child sex with reduced RRs in females, although the number of females with ASD was limited (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The associations between use of prenatal vitamins in the first month of pregnancy and both ASD and non-TD did not appear to differ substantially across child cognitive functioning. Thirty-three mothers (13.7%), including 12 in the ASD, 4 in the non-TD, and 17 in the TD groups, reported taking other multivitamins during the first month of pregnancy.

The highest tertile of total mean folic acid supplemental intake during the first month of pregnancy was associated with the greatest reduction in estimated ASD risk, and the P value for trend was statistically significant before and after adjustment for maternal education (unadjusted RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.15-0.84; P = .02 vs adjusted RR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.17-0.99; P = .048; Table 3). No evidence was found for reduced non-TD risk associated with the highest tertile of folic acid intake or for a dose trend (unadjusted RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.57-1.77; P = .99 and adjusted RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.72-2.49; P = .36; Table 3). Folic acid intake at or above 600 μg was also associated with statistically significantly lower ASD risk (adjusted RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.31-0.82) but no association with non-TD (adjusted RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.77-1.84; Table 3). The top 2 tertiles of total mean daily iron intake during the first month of pregnancy were associated with reduced estimated ASD risk compared with the bottom tertile, and evidence of a dose trend was found (tertile 2, adjusted RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.98;tertile 3, adjusted RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30-0.92; adjusted P = .02; Table 3). Iron intake at or above 27 mg was not statistically significantly associated with ASD (adjusted RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.40- 1.09). No evidence of an association or a dose trend was observed between iron intake and non-TD (adjusted RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.62-1.41; Table 3). Sensitivity analyses using the TMLE approach showed similar effect estimates between ASD and the second and third tertiles of folic acid and iron compared with the first; TMLE findings for non-TD were similar for tertiles of iron, but the highest tertile of folic acid was associated with increased risk for non-TD in all TMLE models (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Maternal Mean Daily Intake of Folic Acid and Iron Supplements in the First Month of Pregnancy With Child Outcome.

| Maternal Mean Daily Supplemental Intake in First Month of Pregnancy | 36-mo Outcome, No. (%) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | Non-TD | TD | ASD vs TD | Non-TD vs TD | ASD vs TD | Non-TD vs TD | |

| Folic acid | |||||||

| Tertile 1 (0-57 μg) | 27 (49.1) | 18 (30.0) | 35 (27.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Tertile 2 (80-800 μg) | 23 (41.8) | 28 (46.7) | 64 (50.8) | 0.61 (0.39-0.95) | 0.90 (0.55-1.46) | 0.63 (0.40-0.98) | 1.00 (0.61-1.62) |

| Tertile 3 (805-4800 μg) | 5 (9.1) | 14 (23.3) | 27 (21.4) | 0.36 (0.15-0.84) | 1.00 (0.57-1.77) | 0.42 (0.17-0.99) | 1.34 (0.72-2.49) |

| P value for trend | NA | NA | NA | .02 | .99 | .048 | .36 |

| Below recommendation (<600 μg) | 36 (65.5) | 22 (36.7) | 49 (38.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| At/above recommendation (≥600 μg) | 19 (34.6) | 38 (63.3) | 77 (61.1) | 0.47 (0.29-0.75) | 1.07 (0.69-1.65) | 0.51 (0.31-0.82)b | 1.19 (0.77-1.84)c |

| Iron | |||||||

| Tertile 1 (0 mg) | 30 (54.6) | 25 (41.7) | 39 (31.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Tertile 2 (0.5-27.0 mg) | 13 (23.6) | 18 (30.0) | 43 (34.1) | 0.53 (0.31-0.92) | 0.76 (0.46-1.24) | 0.57 (0.33-0.98) | 0.85 (0.52-1.40) |

| Tertile 3 (27.2-328 mg) | 12 (21.8) | 17 (28.3) | 44 (34.9) | 0.49 (0.28-0.87) | 0.71 (0.43-1.18) | 0.52 (0.30-0.92) | 0.75 (0.45-1.23) |

| P value for trend | NA | NA | NA | .01 | .19 | .02 | .25 |

| Below recommendation (<27 mg) | 39 (70.9) | 35 (58.3) | 71 (56.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| At/above recommendation (≥27 mg) | 16 (29.1) | 25 (41.7) | 55 (43.7) | 0.64 (0.39-1.05) | 0.95 (0.62-1.45) | 0.66 (0.40-1.09)d | 0.93 (0.62-1.41)e |

Abbreviations: ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder; NA, not applicable; Non-TD, nontypical development; RR, relative risk; TD, typical development.

Adjusted for maternal education in the ASD model and for child white or non-white race, maternal age and education, insurance delivery type, and maternal intention to become pregnant (yes or no) in the non-TD model. In the adjusted models for non-TD, 3 children were excluded because of missing covariates.

When further adjusted for iron intake at or above 27 mg, the ASD RR was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.16-0.90).

When further adjusted for iron intake at or above 27 mg, the non-TD RR was 1.65 (95% CI, 0.95-2.85).

When further adjusted for folic acid intake at or above 600 μg, the ASD RR was 1.47 (95% CI, 0.61-3.55).

When further adjusted for folic acid intake at or above 600 μg, the non-TD RR was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.45-1.31).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between risk of ASD recurrence and maternal prenatal vitamin use. We found that in this high-risk cohort, maternal prenatal vitamin use near conception was associated with a reduction in ASD risk in younger siblings similar to the decreased risk observed in the general population. Considering the potential for greater genetic susceptibility in these families, these findings, if replicated, imply that susceptibility could potentially be overcome by environmental manipulation. Twin studies3,5,29 suggest that the early environment contributes to the development of ASD in addition to shared genetics, and gene-environment interaction effects are likely.30,31 Furthermore, this association appeared to be specific to ASD and was not observed for other non-TD outcomes, which may be because the non-TD group was heterogeneous and, according to previous studies of other high-risk samples,32,33 was likely composed of multiple small subgroups with diverse outcomes, not all of which were detectable at 3 years of age.

MARBLES collected information on vitamin use by month, which allows for greater characterization of timing than the information collected in most ASD studies. The timing implicated in this study is congruent with previous studies showing that the periconceptional period could be particularly critical in ASD origin and prenatal vitamin use.6,7,9 The association between prenatal vitamin use and reduced ASD risk could be owing to any of the many nutrients contained in these vitamins. As suggested in previous studies, iron and especially folic acid are likely contributors given their high content in prenatal vitamins (compared with multivitamins, which were not associated with lower ASD risk), their importance in neurodevelopment, their depletion during pregnancy, and (especially for folic acid) the timing of their effect.7,8,9,34

We observed modest evidence of a dose trend in which the highest tertile of mean daily folic acid supplementation was associated with a slightly greater reduction in ASD RR. Folic acid intake above the amount recommended for pregnancy (≥600 μg) was associated with lower ASD risk. Multivitamins, which typically contain less than 400 μg, were not associated with this decreased ASD risk, which implies that the association between prenatal vitamin use and ASD in high-risk siblings could, at least partly, be attributed to the high folic acid content in prenatal vitamins, as has been previously observed in general population studies,8,9,14 but other nutrients like iron could also be playing a role.34 The inverse association with folic acid intake compared with iron intake appeared more specific to ASD, which could suggest differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes by nutrient content in prenatal vitamin supplements. Because intake of folic acid and iron was highly correlated, our ability to examine their independent effects was limited; however, when we examined the intake of these 2 nutrients above the recommended dose for the first pregnancy month in the same model, the folic acid association remained statistically significant. Additional studies are needed to more rigorously investigate which nutrient might be driving the association with reduced ASD risk.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Even though the proportion of younger siblings with ASD was consistent with that of the much larger sample in the Baby Siblings Research Consortium,17 the sample size in this study provided limited power to detect differences across strata; however, to our knowledge, this research is the largest study to date that enrolled high-risk siblings before or during pregnancy and that prospectively collected supplement intake. This study assessed many potential confounding factors; however, the possibility of residual confounding or confounding by unmeasured factors cannot be ruled out. Prenatal vitamin use starting before pregnancy as recommended is a potential marker of good health literacy and is associated with many health-conscious behaviors, such as maternal exercise and avoidance of toxicant exposures that could decrease background ASD risk in children.

Conclusions

This study is the first to our knowledge to suggest that maternal prenatal vitamin intake during the first month of pregnancy may reduce ASD recurrence by half in younger siblings of children with ASD in high-risk families. These findings, if replicated, could have important public health implications for affected families. Future work should examine the contributions of specific nutrients from supplements as well as food sources, overall diet quality, and biologic measurements of nutrient status, as well as investigate dose thresholds, interactions with genetic variants, and potential mechanisms.

eMethods. MARBLES Interview Questions on Vitamins and Supplements

eTable 1. Results of the Sensitivity Analyses Using MLE and TMLE Approaches for the 233 Participants With Complete Covariate Data

eTable 2. Stratified Adjusted and Unadjusted Associations Between Prenatal Vitamin Use During the First Month of Pregnancy and Diagnosis

eTable 3. Results of the Sensitivity Analyses Examining Associations of Maternal Daily Average Supplemental Folic Acid and Iron Intake During the First Month of Pregnancy in Relation to Child Diagnosis Using MLE and TMLE Approaches for the 233 Participants With Complete Covariate Data

eFigure 1. Unadjusted Relative Risk for Association Between Reported Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Supplements From 6 Months Before Pregnancy Through the End of Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Non-Typical Development (Non-TD)

eFigure 2. Adjusted Relative Risk for Association Between Reported Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Supplements From 6 Months Before Pregnancy Through the End of Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Non-Typical Development (Non-TD)

References

- 1.Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(6):1-23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuk O, Hechter E, Sunyaev SR, Lander ES. The mystery of missing heritability: genetic interactions create phantom heritability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(4):1193-1198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119675109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1095-1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risch N, Hoffmann TJ, Anderson M, Croen LA, Grether JK, Windham GC. Familial recurrence of autism spectrum disorder: evaluating genetic and environmental contributions. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1206-1213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H, Hultman CM, Reichenberg A. The familial risk of autism. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1770-1777. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyall K, Schmidt RJ, Hertz-Picciotto I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):443-464. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt RJ, Hansen RL, Hartiala J, et al. Prenatal vitamins, one-carbon metabolism gene variants, and risk for autism. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):476-485. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821d0e30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt RJ, Tancredi DJ, Ozonoff S, et al. Maternal periconceptional folic acid intake and risk of autism spectrum disorders and developmental delay in the CHARGE (CHildhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) case-control study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):80-89. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surén P, Roth C, Bresnahan M, et al. Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA. 2013;309(6):570-577. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.155925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steenweg-de Graaff J, Ghassabian A, Jaddoe VW, Tiemeier H, Roza SJ. Folate concentrations during pregnancy and autistic traits in the offspring: the Generation R Study. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(3):431-433. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun JM, Froehlich T, Kalkbrenner A, et al. Brief report: are autistic-behaviors in children related to prenatal vitamin use and maternal whole blood folate concentrations? J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2602-2607. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2114-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Li K, Zhao D, Li L. The association between maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children: a meta-analysis. Mol Autism. 2017;8:51. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0170-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vázquez L I, Canals J, Arija V. Review and meta-analysis found that prenatal folic acid was associated with a 58% reduction in autism but had no effect on mental and motor development [published online November 22, 2018]. Acta Paediatr. doi: 10.1111/apa.14657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine SZ, Kodesh A, Viktorin A, et al. Association of maternal use of folic acid and multivitamin supplements in the periods before and during pregnancy with the risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):176-184. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virk J, Liew Z, Olsen J, Nohr EA, Catov JM, Ritz B. Preconceptional and prenatal supplementary folic acid and multivitamin intake and autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2016;20(6):710-718. doi: 10.1177/1362361315604076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertz-Picciotto I, Schmidt RJ, Walker CK, et al. A prospective study of environmental exposures and early biomarkers in autism spectrum disorder: design, protocols, and preliminary data from the MARBLES study. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(11):117004. doi: 10.1289/EHP535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: a Baby Siblings Research Consortium study. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e488-e495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and Its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205-223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005592401947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullen EM. Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozonoff S, Young GS, Belding A, et al. The broader autism phenotype in infancy: when does it emerge? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):398-407.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chawarska K, Shic F, Macari S, et al. 18-Month predictors of later outcomes in younger siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: a Baby Siblings Research Consortium study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(12):1317-1327.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(5):693-705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop SL. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2). 2nd ed Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199-200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Laan MJ, Rose S. Targeted Learning: Causal Inference for Observational and Experimental Data. New York, NY: Springer Series in Statistics; 2011. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9782-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, Hultman C, Larsson H, Reichenberg A. The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1182-1184. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tordjman S, Somogyi E, Coulon N, et al. Gene × environment interactions in autism spectrum disorders: role of epigenetic mechanisms. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:53. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaste P, Leboyer M. Autism risk factors: genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14(3):281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brian J, Bryson SE, Smith IM, et al. Stability and change in autism spectrum disorder diagnosis from age 3 to middle childhood in a high-risk sibling cohort. Autism. 2016;20(7):888-892. doi: 10.1177/1362361315614979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shephard E, Milosavljevic B, Pasco G, et al. ; BASIS Team . Mid-childhood outcomes of infant siblings at familial high-risk of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(3):546-557. doi: 10.1002/aur.1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt RJ, Tancredi DJ, Krakowiak P, Hansen RL, Ozonoff S. Maternal intake of supplemental iron and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(9):890-900. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. MARBLES Interview Questions on Vitamins and Supplements

eTable 1. Results of the Sensitivity Analyses Using MLE and TMLE Approaches for the 233 Participants With Complete Covariate Data

eTable 2. Stratified Adjusted and Unadjusted Associations Between Prenatal Vitamin Use During the First Month of Pregnancy and Diagnosis

eTable 3. Results of the Sensitivity Analyses Examining Associations of Maternal Daily Average Supplemental Folic Acid and Iron Intake During the First Month of Pregnancy in Relation to Child Diagnosis Using MLE and TMLE Approaches for the 233 Participants With Complete Covariate Data

eFigure 1. Unadjusted Relative Risk for Association Between Reported Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Supplements From 6 Months Before Pregnancy Through the End of Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Non-Typical Development (Non-TD)

eFigure 2. Adjusted Relative Risk for Association Between Reported Maternal Prenatal Vitamin Supplements From 6 Months Before Pregnancy Through the End of Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Non-Typical Development (Non-TD)