Key Points

Question

What are the global trends of case-fatality risk in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 94 published studies including 7561 patients showed a declining trend of case-fatality risk in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock, with persistent significant disparities between developing and developed countries.

Meaning

More attention and concerted endeavors to improve medical care in resource-poor settings are required to alleviate the overall global burden of mortality in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of children with severe sepsis and septic shock seeks to elucide patterns in case-fatality rates over time.

Abstract

Importance

The global patterns and distribution of case-fatality rates (CFRs) in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock remain poorly described.

Objective

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of children with severe sepsis and septic shock to elucidate the patterns of CFRs in developing and developed countries over time. We also described factors associated with CFRs.

Data Sources

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Excerpta Medica database, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane Central systematically for randomized clinical trials and prospective observational studies from earliest publication until January 2017, using the keywords “pediatric,” “sepsis,” “septic shock,” and “mortality.”

Study Selection

Studies involving children with severe sepsis and septic shock that reported CFRs were included. Retrospective studies and studies including only neonates were excluded.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We conducted our systematic review and meta-analysis in close accordance to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Pooled case-fatality estimates were obtained using random-effects meta-analysis. The associations of study period, study design, sepsis severity, age, and continents in which studies occurred were assessed with meta-regression.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Meta-analyses to provide pooled estimates of CFR of pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock over time.

Results

Ninety-four studies that included 7561 patients were included. Pooled CFRs were higher in developing countries (31.7% [95% CI, 27.3%-36.4%]) than in developed countries (19.3% [95% CI, 16.4%-22.7%]; P < .001). Meta-analysis of CFRs also showed significant heterogeneity across studies. Continents that include mainly developing countries reported higher CFRs (adjusted odds ratios: Africa, 7.89 [95% CI, 6.02-10.32]; P < .001; Asia, 3.81 [95% CI, 3.60-4.03]; P < .001; South America, 2.91 [95% CI, 2.71-3.12]; P < .001) than North America. Septic shock was associated with higher CFRs than severe sepsis (adjusted odds ratios, 1.47 [95% CI, 1.41-1.54]). Younger age was also a risk factor (adjusted odds ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.94-0.96] per year of increase in age). Earlier study eras were associated with higher CFRs (adjusted odds ratios for 1991-2000, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.13-1.37]; P < .001) compared with 2011 to 2016. Time-trend analysis showed higher CFRs over time in developing countries than developed countries.

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite the declining trend of pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock CFRs, the disparity between developing and developed countries persists. Further characterizations of vulnerable populations and collaborations between developed and developing countries are warranted to reduce the burden of pediatric sepsis globally.

Introduction

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in children. It is often associated with multiorgan dysfunction from dysregulated systemic host immune response to infection.1,2 Globally, sepsis and infections caused 6.3 deaths of 1000 live births among children younger than 5 years.3 Once diagnosed, the case-fatality rate (CFR) from pediatric sepsis is estimated to be 25%.4 Recognizing the current magnitude of sepsis burden, the World Health Organization (WHO) recently passed a resolution to highlight sepsis as a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide and strengthened its stance to mitigate the global burden of sepsis.5

Despite being a significant public health burden, the global CFRs of pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock remain poorly described.6,7,8 A meta-analysis of studies of adult sepsis demonstrated a 3% decrease in global CFR annually from 1991 to 2009, indicating improvements in public health measures and management of sepsis.9 However, to our knowledge, no such estimates are available in the pediatric population. Existing individual studies only provide a snapshot of CFR at a specific time (or over a specific period) and place, rather than a pattern or trajectory over time, which is more useful for comparisons of mortality.5,10 Generating pooled global CFRs will also allow health care centers to assess their progress in the management of pediatric sepsis, highlight vulnerable populations of children, and enable meaningful comparisons of risk factors and outcomes in pediatric sepsis management.

We therefore aim to summarize the available CFRs on pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock published in the literature up to January 2017 to determine CFRs in children with severe sepsis and septic shock over time. In addition, we hypothesized that there are important factors associated with mortality, including geographical regions, level of economic development, study design, and sepsis category.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in close accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. It is registered in PROSPERO with the registration number CRD42017049853.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We identified the patient, intervention, control, outcome, and study design (PICOS) as children younger than 18 years having severe sepsis or septic shock, with CFR being the primary outcome of interest. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Excerpta Medica (Embase) database, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane Central databases to identify eligible studies. The search was conducted on and included studies up to January 10, 2017. Keywords used include “pediatric,” “sepsis,” “severe sepsis,” “septic shock,” and “mortality.” The search strategy is detailed in eTable 1 in the Supplement. No limits or filters were used.

We included studies that fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) a randomized clinical trial (RCT) or prospective study design, (2) a study population with severe sepsis or septic shock by any definition or merely the label of severe sepsis or septic shock, and (3) reported mortality. Studies involving adults, post hoc analysis of an existing RCT (if there were no duplicate data with another included study), database and registry studies, and studies with both retrospective and prospective arms were included if the subpopulation of interest fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We included studies from all languages.

Studies involving exclusively neonatal and perinatal sepsis are excluded. We excluded studies involving primarily neonatal and/or perinatal sepsis owing to the differences in epidemiology and pathophysiology compared with pediatric sepsis.11 In addition, pediatric sepsis is often managed in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), a distinct clinical area to where neonatal and perinatal sepsis are often managed (ie, neonatal intensive care units). Retrospective studies were excluded to minimize selection and recall biases. We excluded abstracts because they do not provide adequate description of studies on which the quality of studies can be assessed. We also excluded studies with fewer than 20 participants, to avoid publication biases, reporting biases, and small-study effects that could cause extreme estimations of CFRs.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two reviewers (B.T. and J.C.J.W.K.) independently conducted the database search and screened for potential studies by examining the titles and abstracts. The full-text articles of shortlisted studies were then assessed for eligibility. Reference lists of obtained articles and relevant review articles were hand searched. We contacted the corresponding authors for missing or unreported data. Disagreements on study eligibility or data extraction were resolved by consensus or with input from a third independent reviewer (J.J.-M.W.). A standardized data collection form was used by 2 independent reviewers (B.T. and J.J.-M.W.) to extract relevant data from the eligible studies. When required, translations of included studies were performed by native speakers of the language. We extracted data on study characteristics (eg, study year, study design, geographical location, and continent), patient characteristics (eg, age, severity of sepsis, microbiological data, and Pediatric Risk of Mortality score) and outcome (CFR) from the placebo arms of RCTs or prospective cohort studies. A priori, geographical continents and classification of countries into developed or developing economies were determined according to the United Nations country classification system.12,13

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess risk of bias for RCTs at the outcome level.14 The scale includes the presence of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and researchers, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess risk of bias for prospective observational studies at the outcome level.15 This scale was selected because it was originally developed to assess the risk of bias of case-control and cohort studies. In addition, the scale is suited to assess the risk of bias of noninterventional observational studies. Briefly, this scale has 3 assessment areas: (1) selection (cohort representativeness, exposure ascertainment, and demonstration that outcome of interest was absent at the start of the study), (2) comparability (assessment of the cohorts’ comparability based on the design or analyses), and (3) outcome (objective assessment of outcomes, adequate study period, and length of follow-up period).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages while continuous variables were summarized as means with SDs or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. We performed meta-analysis using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model to obtain pooled CFR estimates and associated exact binomial 95% CIs. The inverse of total number of patients in each study was used as the weight in the meta-regression models. We used I2 statistics to quantify heterogeneity across studies, and an I2 statistic of 80% or more was considered to indicate considerable heterogeneity. However, owing to the broad review question resulting in an inherently heterogeneous population among included studies, we accepted I2 statistics up to 95% for inclusion in a meta-analysis.

Cumulative meta-analysis was performed based on the study year, which was considered to be midway through the study recruitment period. In this cumulative meta-analysis, selected studies were arranged in ascending order of trial period, and then multiple meta-analyses were performed by accumulating studies consecutively in a sequence of trial period. A priori, we intended to investigate the contribution of the following covariates by weight-adjusted multivariable logistic meta-regression: study design (RCT vs observational), continents, sepsis severity (severe sepsis vs septic shock), and period, as well as any other covariate that was significant in the univariate analysis. Subgroup meta-analysis was also performed based on the a priori covariates. Studies conducted over multiple continents were excluded from the multivariable logistic regression owing to the difficulty in attributing the study location. Measures of association were expressed as odd ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs. We performed a sensitivity analysis including only studies with a low risk of bias, as assessed by the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Bubble plots for weight-adjusted estimated CFRs for study design (RCT vs observational), continents, sepsis severity (severe sepsis vs septic shock), and period were created. The size of the bubble is proportional to the total number of patients recruited in the corresponding study.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3 (Biostat). All tests performed were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

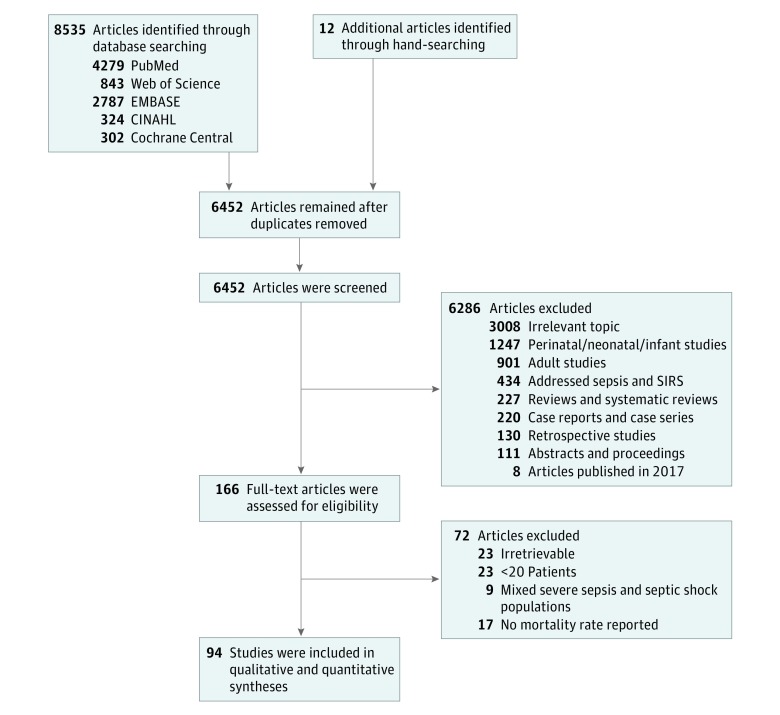

The database search and hand search of reference lists yielded a total of 8535 and 12 articles, respectively (Figure 1). After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 94 studies4,6,7,8,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104 that included a combined 7561 patients were eligible for analysis. Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1 and eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement. The mean (SD) age of the children in the included studies was 4.8 (2.3) years. Children from developing countries had a younger mean (SD) age (4.3 [2.3] years) than those in developed countries (5.3 [2.1] years; P = .03).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Included Studies.

SIRs indicates systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Variables | Countries, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Developed Countries (n = 51) | Developing Countries (n = 43) | All Studies (N = 94) | |

| Study design | |||

| Observational | 45 (88) | 37 (86) | 82 (87) |

| Randomized clinical trial | 6 (12) | 6 (14) | 12 (13) |

| Sepsis severity | |||

| Septic shock | 42 (82) | 33 (77) | 75 (80) |

| Severe sepsis | 9 (18) | 10 (23) | 19 (20) |

| Study continents | |||

| Africa | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Asia | 0 | 29 (67) | 29 (31) |

| Australia | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Europe | 25 (49) | 0 | 25 (27) |

| North America | 21 (41) | 0 | 21 (22) |

| South America | 0 | 13 (30) | 13 (14) |

| Age of patients, mean (SD), y | 5.3 (2) | 4.3 (2) | 4.8 (2) |

| Predominant (>50%) agent causing sepsis | |||

| Gram-positive | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Gram-negative | 21 (41) | 6 (14) | 27 (28) |

| Mixed bacterial | 11 (22) | 11 (26) | 22 (23) |

| Parasite | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| No predominant agent | 6 (14) | 10 (23) | 16 (17) |

| PRISM score, median (IQR) | 15.3 (13.0-16.8) | 15.6 (11.5-20.7) | 15.5 (12.4-18.7) |

| Length of PICU stay, median (IQR), d | 11.7 (6.7-16.3) | 8.4 (6.0-14.6) | 9.9 (6.0-14.9) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PRISM, Pediatric Risk of Mortality.

Of all the studies, 534,6,16,17,18,19,22,26,27,29,30,31,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,67,69,71,72,75,76,80,82,84,86,89,90,92,93,94,95,99,101,103 (56%) reported the main causal mechanism of sepsis among the study population. Gram-negative bacteria were the predominant (>50%) source of sepsis in developed countries (2117,18,19,29,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,60,103 of 40 studies4,6,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,37,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,103,104 [53%]) compared with developing countries (669,72,80,94,95,101 of 297,8,62,63,67,69,71,72,75,76,80,81,82,83,84,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,99,100,101,102 [21%]; P = .06).

Fifty-seven studies4,6,8,10,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,30,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,46,47,49,50,51,54,61,62,63,64,66,68,71,72,74,76,77,79,80,82,84,86,87,89,90,95,96,97,98,101,102,104 (59%), including 4886 of 7561 patients (65%), reported severity of illness scores (eg, Pediatric Risk of Mortality, Pediatric Index of Mortality, and Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction scores). There were no differences in the severity of illness scores between developed and developing countries.

Seventy-five6,8,16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,68,70,71,72,73,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,89,93,95,96,100,101,102,103,104 of 94 studies (80%) came from Asia, Europe, and North America. Six10,18,19,61,62,65 of the 12 RCTs10,16,17,18,19,61,62,63,64,65,66,103 (50%) and 2220,21,22,24,33,34,37,38,47,48,49,50,75,76,77,83,89,93,97,98,99,102 of 82 observational studies4,6,7,8,10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,104 (27%) had low risk of bias, respectively (eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement).

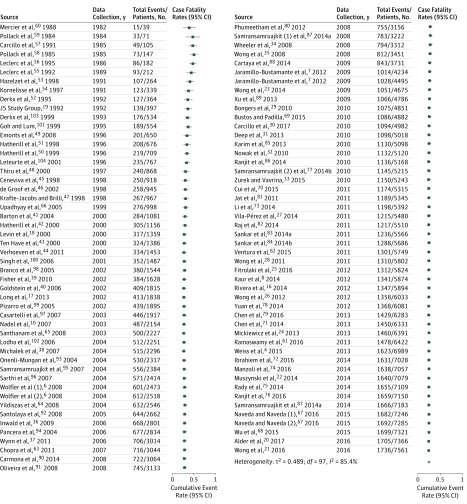

Overall, the pooled CFR was 24.7% (95% CI, 21.9%-27.7%) (Figure 2). Studies conducted in developed countries had lower CFRs (19.3% [95% CI, 16.4%-22.7%]) than those in developing countries (31.7% [95% CI, 27.3%-36.4%]; P < .001; eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement). Pooled CFRs for single-continent studies from North America and Europe were 21.3% (95% CI, 11.4%-36.3%) and 21.1% (95% CI, 16.7%-26.2%), respectively. Single-continent studies from Africa, Asia, and South America had pooled CFRs of 50.0% (95% CI, 32.8%-67.2%), 36.6% (95% CI, 30.8%-42.9%), and 28.5% (95% CI, 20.4%-38.4%), respectively. Observational study design was associated with higher CFRs (27.1% [95% CI, 19.2%-36.8%]) than RCTs (25.6% [95% CI, 24.5%-26.7%]; P < .001), while septic shock was associated with a higher CFR (26.5% [95% CI, 23.2%-30.1%]) than severe sepsis was (19.2% [95% CI, 14.7%-24.8%]; P < .001; eFigures 3-6 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Cumulative Forest Plot of Case-Fatality Rates From All Included Studies.

Forest plot is organized by year of data collection.

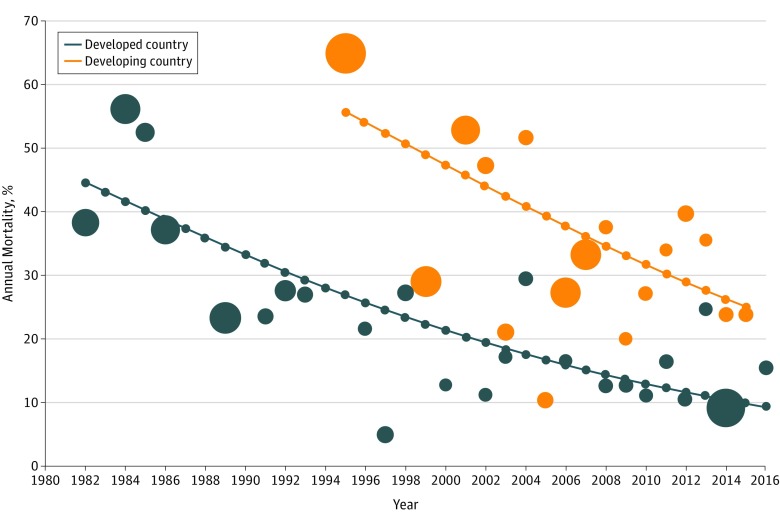

Pooled CFRs decreased from 43.1% (95% CI, 28.9%-58.6%) in the years 1981 to 1990 to 22.8% (95% CI, 18.7%-27.5%) in 2011 to 2016 (P < .001). This pattern was also seen when the annual pooled CFRs were stratified according to socioeconomic status (ie, by developing vs developed countries) (Figure 3). There was significant heterogeneity for CFRs across studies and subgroups, with I2 ranging from 80% to 89%. A sensitivity analysis including only low-risk studies showed similar results (eFigures 7 and 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Pattern of Pooled Weighted Case-Fatality Rates From 1982 to 2016 for All Included Studies.

The covariates included in the multivariable model were those determined a priori (developing status of the country, study design [RCT vs observational], sepsis severity [severe sepsis vs septic shock] and time of study) and age, which was significant on univariate analysis (Table 2). In this analysis, 44,10,18,41 of 944,6,7,8,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104 studies (6%) were conducted in multiple continents and hence excluded. The odds of fatality in developing countries were more than 4 times (adjusted odds ratio, 4.40 [95% CI, 3.84-5.56]) higher than developed countries. Other factors associated with increased CFRs were septic shock (adjusted odds ratio, 1.47 [95% CI, 1.41-1.54]; P < .001), younger age (adjusted odds ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.94-0.96]; P < .001), and study years between 1991 and 2000 (compared with 2011-2016; adjusted odds ratio, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.13-1.37]; P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Meta-regression Analysis of Association Between Study Variables and Mortality.

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P Value | |

| Country status | ||||

| Developed | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Developing | 2.31 (2.23-2.38) | <.001 | 4.40 (3.84-5.56) | <.001 |

| Study design | ||||

| Randomized clinical trial | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Observational studies | 0.92 (0.84-1.00) | .07 | NA | NA |

| Severity | ||||

| Severe sepsis | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Septic shock | 1.38 (1.33-1.43) | <.001 | 1.47 (1.41-1.54) | <.001 |

| Age, per y | 0.93 (0.92-0.94)a | <.001 | 0.95 (0.94-0.96)a | <.001 |

| Period | ||||

| 2011-2016 | 1 [Reference] | <.001b | 1 [Reference] | <.001b |

| 1991-2000 | 0.83 (0.79-0.86) | <.001 | 1.24 (1.13-1.37) | <.001 |

| 2001-2010 | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.09-1.21) | .26 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Per year of increase in age.

Refers to overall (2 df) P value.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis is, to our knowledge, the first study that provides estimated global case-fatality trajectories from pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock over time across both developing and developed nations. Our review showed a high overall CFR associated with pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock (25%). These CFRs have declined from 1981 to 1990 to 2011 to 2016. We showed that developing countries continue to shoulder higher CFRs compared with developed countries. Factors that were independently associated with increased CFRs include geographical location, younger age, septic shock, and an earlier era of study.

Our study showed that pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock continue to be an important cause of child mortality. The WHO’s 2016 data on causes of child mortality reported that sepsis and infection-associated causes continue to contribute heavily to the burden of mortality, up to 6.3 of every 1000 live births among children aged 0 to 4 years.3 Our estimates of global CFRs from pediatric sepsis were higher than the estimates from a recent systematic review by Fleischmann-Struzek et al.105 This prior systematic review reported that the mortality rate for pediatric severe sepsis ranged from 9% to 20%. In contrast, our CFR estimate from pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock was 25%. This difference may be owing to our focus only on populations of children with both severe sepsis and septic shock. We have also attempted to gather more data from studies in developing countries, which made up 43% of the patient population in this study.4,105 This is especially important, since these countries may not maintain a large database of pediatric populations with sepsis. Our estimate is more consistent with the figure reported by the Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies (SPROUT) study, a global cross-sectional study that recruited pediatric patients with severe sepsis and septic shock from 26 developed and developing countries in 2013 and 2014, which reported similar mortality of 25%.4 Our study has supported the prevailing evidence in the literature that sepsis continues to be an important cause of mortality among children.

Our time-trend analysis showed that the CFRs from pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock had a general decline over 10-year date ranges (1991-2000 to 2001-2010 and 2011-2016). The rate of decline in CFRs in developing countries was similar to those of developed countries. Our study results further corroborated WHO data from 2016,3 which showed that the general mortality trend of sepsis among children aged 0 to 4 years declined from 4.1 of 1000 live births in 2000 to 2.8 of 1000 live births in 2016. The improvement in CFRs from pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock is likely owing to multiple factors, including the implementation of sepsis management guidelines worldwide, such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, which was launched in 2004 and subsequently revised in 2008, 2012 and 2017; advancements in hospital and PICU care; and improvements in public health measures (eg, access to vaccines, eradication of malnutrition, prevention of spread of infectious diseases, and addressing antimicrobial resistance) in developing countries.106,107,108,109 In this review, there is a general improvement of reported treatment protocols for pediatric sepsis over the years, with the assimilation of published sepsis management guidelines in the centers’ algorithms in both developed and developing countries. More sensitive modes of identification and monitoring of pediatric sepsis may also contribute to earlier intervention and the decline of CFRs. The WHO with its partners, the United Nations Children's Fund, Food and Agriculture Organization, and World Organization for Animal Health, have further developed global action plans to continually improve these issues with the aim of reducing the burden of sepsis worldwide.5 Another systematic review and meta-analysis on pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome showed similar decline in mortality trends over time, indicating improvements in PICU care standards worldwide.110

Despite similar rates of decline, we found that annual CFRs in developing countries were consistently higher than those in developed countries. We have attempted to fill the knowledge gap on population-level epidemiological data from low-income and middle-income countries highlighted by Fleischmann-Struzek et al105 and the SPROUT study4 by systematically reviewing the published observational studies and RCTs on pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock in developing countries. The SPROUT study4 reported no significant difference in pediatric sepsis mortality between developed and developing countries. In contrast, we found that CFRs from pediatric sepsis in developing countries were higher than those in developed countries. This difference in findings can be attributed to the differences in proportion of data from developing and developed countries between the 2 studies. The study designs (an analysis over time in our systematic review vs the point-prevalence design of the SPROUT study) were also different.

Similar to our study results, the WHO data from 2016 showed that despite the decline in mortality rates for sepsis among children age 0 to 4 years in low-income and high-income countries, low-income countries persistently have higher mortality rates than high-income countries.3 Resource-poor developing countries have cited several reasons for increased sepsis mortality: the lack of access to primary care and intensive care unit beds, as well as monitoring devices and drugs required to follow guidelines of sepsis management, in addition to basic needs, such as clean water and electricity.111,112 Fluids for intravenous infusion may be scarce, choices of fluids are restricted by costs, and advanced treatment modalities to support organ functions crucial in severe sepsis and septic shock may be limited.113 Malnutrition, secondary infections, and multiple hospitalizations among children in developing countries further increase the probability of sepsis evolving into septic shock and consequently worsen the mortality burden compared with children in developed countries.114

The 2017 World Health Assembly also identified the difficulty in estimating the global burden of sepsis accurately and emphasized the need for robust data from low-income and middle-income countries on the burden of sepsis.3 Our systematic review and meta-analysis results provided data on pooled CFRs from severe sepsis and septic shock in pediatric patients from both developing and developed countries over time. These patterns and pooled CFRs can be used by governments and public health scientists to plan future health initiatives. Future pediatric sepsis studies may also use the results presented here for sample size calculations and benchmarking PICU performance.

Limitations

There are several important limitations to our systematic review and meta-analysis. First, we did not include unpublished data and data reported in abstract form, which may result in publication bias. Our attempt to elucidate more factors associated with CFRs (eg, chronic comorbid conditions and multiple-organ dysfunction) was limited by the data available from the included studies. Data on time prior to presentation to medical attention were also not collected from the studies included in this systematic review. Another limitation is our inability to assess the influence of the timing of recognition of sepsis in the primary care setting. Also, owing to difficulty in assigning the geography and level of economic development to multicenter studies, these studies were excluded from the meta-regression. Exclusion of these larger studies may have introduced selection bias to this analysis. Last, to obtain a comprehensive pattern in CFRs over time, we decided to include a heterogeneous group of studies in this meta-analysis, and this may have compromised the precision of our study.

Conclusions

The overall CFRs associated with pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock remains high (25%). Factors independently associated with increased CFRs include the level of economic development of the country, the presence of septic shock (rather than severe sepsis), a younger age in patients, and an earlier date of study. Efforts to improve medical care in resource-poor settings are needed to decrease the global mortality in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock.

eTable 1. Search strategies for databases

eTable 2. Characteristics of included studies conducted in developed countries

eTable 3. Characteristics of included studies conducted in developing countries

eTable 4. Risk of bias of individual randomized controlled trials

eTable 5. Risk of bias of individual observational studies

eFigure 1. Cumulative forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies conducted in developed countries

eFigure 2. Cumulative forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies conducted in developing countries

eFigure 3. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from randomized controlled trials

eFigure 4. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from observational studies

eFigure 5. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies with severe sepsis populations

eFigure 6. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies with septic shock populations

eFigure 7. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from high quality studies with low risk of bias

eFigure 8. Time-trend of pooled weighted mortality rates from 1982 to 2016 (by year of study) for high-quality studies with low risk of bias

References

- 1.Watson RS, Carcillo JA. Scope and epidemiology of pediatric sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3)(suppl):S3-S5. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161289.22464.C3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Department of Evidence, Information and Research; Maternal Child Epidemiology Estimation MCEE-WHO methods and data sources for child causes of death 2000-2016. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/childcod_methods_2000_2016.pdf?ua=1. 2018. Accessed June 24, 2018.

- 4.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. ; Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies (SPROUT) Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(10):1147-1157. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2323OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Executive Board EB140/12: Improving the prevention, diagnosis and clinical management of sepsis. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB140/B140_12-en.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed 10 January 2018.

- 6.Wolfler A, Silvani P, Musicco M, Antonelli M, Salvo I; Italian Pediatric Sepsis Study (SISPe) group . Incidence of and mortality due to sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock in Italian pediatric intensive care units: a prospective national survey. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(9):1690-1697. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1148-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaramillo-Bustamante JC, Marín-Agudelo A, Fernández-Laverde M, Bareño-Silva J. Epidemiology of sepsis in pediatric intensive care units: first Colombian multicenter study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13(5):501-508. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823c980f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur G, Vinayak N, Mittal K, Kaushik JS, Aamir M. Clinical outcome and predictors of mortality in children with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock from Rohtak, Haryana: a prospective observational study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18(7):437-441. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.136072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson EK, Rubenstein AR, Radin GT, Wiener RS, Walkey AJ. Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis: a comparative meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):625-631. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadel S, Goldstein B, Williams MD, et al. ; Researching Severe Sepsis and Organ Dysfunction in Children: a Global Perspective (RESOLVE) Study Group . Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis: a multicentre phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9564):836-843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60411-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler DS, Wong HR, Zingarelli B. Pediatric sepsis—part I: “children are not small adults!”. Open Inflamm J. 2011;4:4-15. doi: 10.2174/1875041901104010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Statistics Division Methodology. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/. Published 2018. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- 13.Development Policy and Analysis Division (DPAD) of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat Country classification. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_country_classification.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed November 21, 2018.

- 14.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells GASB, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Published 2018. Accessed November 21, 2018.

- 16.Rivera NG, Chon IF, Zarate MGG, Figueroa COG, García LV. Contrasting two antibiotics schemes in children with septic shock spotted fever of the Rocky Mountains. Revista Mexicana de Pediatria. 2014;81(6):204-208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long EJ, Taylor A, Delzoppo C, et al. A randomised controlled trial of plasma filtration in severe paediatric sepsis. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15(3):198-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin M, Quint PA, Goldstein B, et al. Recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) as adjunctive treatment for children with severe meningococcal sepsis, a randomised trial: rBPI21 Meningococcal Sepsis Study Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):961-967. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02712-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.J5 study Group Treatment of severe infectious purpura in children with human plasma from donors immunized with Escherichia coli J5: a prospective double-blind study. J5 study Group. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(4):695-701. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alder MN, Opoka AM, Lahni P, Hildeman DA, Wong HR. Olfactomedin-4 is a candidate marker for a pathogenic neutrophil subset in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):e426-e432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Anas N, et al. Pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model-II: redefining the pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model with septic shock phenotype. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(11):2010-2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muszynski JA, Nofziger R, Greathouse K, et al. Early adaptive immune suppression in children with septic shock: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):R145. doi: 10.1186/cc13980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong HR, Weiss SL, Giuliano JS Jr, et al. The temporal version of the pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mickiewicz B, Vogel HJ, Wong HR, Winston BW. Metabolomics as a novel approach for early diagnosis of pediatric septic shock and its mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(9):967-976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1726OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitrolaki MD, Dimitriou H, Venihaki M, Katrinaki M, Ilia S, Briassoulis G. Increased extracellular heat shock protein 90α in severe sepsis and SIRS associated with multiple organ failure and related to acute inflammatory-metabolic stress response in children. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(35):e4651. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong HR, Salisbury S, Xiao Q, et al. The pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):R174. doi: 10.1186/cc11652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vila Pérez D, Jordan I, Esteban E, et al. Prognostic factors in pediatric sepsis study, from the Spanish Society of Pediatric Intensive Care. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(2):152-157. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000435502.36996.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, et al. Validation of a gene expression-based subclassification strategy for pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(11):2511-2517. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bongers TN, Emonts M, de Maat MP, et al. Reduced ADAMTS13 in children with severe meningococcal sepsis is associated with severity and outcome. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1181-1187. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carcillo JA, Sward K, Halstead ES, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network Investigators . A systemic inflammation mortality risk assessment contingency table for severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(2):143-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deep A, Goonasekera CDA, Wang Y, Brierley J. Evolution of haemodynamics and outcome of fluid-refractory septic shock in children. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(9):1602-1609. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3003-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowak JE, Wheeler DS, Harmon KK, Wong HR. Admission chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 levels predict survival in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(2):213-216. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b8076c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zurek J, Vavrina M. Procalcitonin biomarker kinetics to predict multiorgan dysfunction syndrome in children with sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Iran J Pediatr. 2015;25(1):e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheeler DS, Devarajan P, Ma Q, et al. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1297-1303. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318169245a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong HR, Cvijanovich N, Wheeler DS, et al. Interleukin-8 as a stratification tool for interventional trials involving pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):276-282. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-131OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inwald DP, Tasker RC, Peters MJ, Nadel S; Paediatric Intensive Care Society Study Group (PICS-SG) . Emergency management of children with severe sepsis in the United Kingdom: the results of the Paediatric Intensive Care Society sepsis audit. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(5):348-353. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.153064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wynn JL, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, et al. The influence of developmental age on the early transcriptomic response of children with septic shock. Mol Med. 2011;17(11-12):1146-1156. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michalek J, Svetlikova P, Fedora M, et al. Bactericidal permeability increasing protein gene variants in children with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(12):2158-2164. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0860-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher JD, Nelson DG, Beyersdorf H, Satkowiak LJ. Clinical spectrum of shock in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):622-625. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ef04b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein B, Nadel S, Peters M, et al. ENHANCE: results of a global open-label trial of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7(3):200-211. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000217470.68764.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barton P, Kalil AC, Nadel S, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in children with severe sepsis. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 pt 1):7-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatherill M, Tibby SM, Turner C, Ratnavel N, Murdoch IA. Procalcitonin and cytokine levels: relationship to organ failure and mortality in pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2591-2594. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ten Have TR, Miller ME, Reboussin BA, James MK. Mixed effects logistic regression models for longitudinal ordinal functional response data with multiple-cause drop-out from the longitudinal study of aging. Biometrics. 2000;56(1):279-287. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00279.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verhoeven JJ, den Brinker M, Hokken-Koelega AC, Hazelzet JA, Joosten KF. Pathophysiological aspects of hyperglycemia in children with meningococcal sepsis and septic shock: a prospective, observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R44. doi: 10.1186/cc10006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceneviva G, Paschall JA, Maffei F, Carcillo JA. Hemodynamic support in fluid-refractory pediatric septic shock. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2):e19. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.2.e19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Groof F, Joosten KF, Janssen JA, et al. Acute stress response in children with meningococcal sepsis: important differences in the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis between nonsurvivors and survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(7):3118-3124. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krafte-Jacobs B, Brilli R. Increased circulating thrombomodulin in children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(5):933-938. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199805000-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiru Y, Pathan N, Bignall S, Habibi P, Levin M. A myocardial cytotoxic process is involved in the cardiac dysfunction of meningococcal septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):2979-2983. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emonts M, de Bruijne EL, Guimarães AH, et al. Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor is associated with severity and outcome of severe meningococcal infection in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(2):268-276. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hatherill M, Tibby SM, Hilliard T, Turner C, Murdoch IA. Adrenal insufficiency in septic shock. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80(1):51-55. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.1.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hatherill M, Tibby SM, Evans R, Murdoch IA. Gastric tonometry in septic shock. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78(2):155-158. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.2.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Derkx B, Marchant A, Goldman M, Bijlmer R, van Deventer S. High levels of interleukin-10 during the initial phase of fulminant meningococcal septic shock. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(1):229-232. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hazelzet JA, de Groot R, van Mierlo G, et al. Complement activation in relation to capillary leakage in children with septic shock and purpura. Infect Immun. 1998;66(11):5350-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kornelisse RF, Hazelzet JA, Hop WC, et al. Meningococcal septic shock in children: clinical and laboratory features, outcome, and development of a prognostic score. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(3):640-646. doi: 10.1086/513759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leclerc F, Hazelzet J, Jude B, et al. Protein C and S deficiency in severe infectious purpura of children: a collaborative study of 40 cases. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(4):202-205. doi: 10.1007/BF01709832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leclerc F, Delepoulle F, Diependaele JF, et al. Severity scores in meningococcal septicemia and severe infectious purpura with shock. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21(3):264-265. doi: 10.1007/BF01701486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carcillo JA, Davis AL, Zaritsky A. Role of early fluid resuscitation in pediatric septic shock. JAMA. 1991;266(9):1242-1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470090076035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollack MM, Fields AI, Ruttimann UE. Distributions of cardiopulmonary variables in pediatric survivors and nonsurvivors of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(6):454-459. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198506000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pollack MM, Fields AI, Ruttimann UE. Sequential cardiopulmonary variables of infants and children in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1984;12(7):554-559. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198407000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mercier JC, Beaufils F, Hartmann JF, Azéma D. Hemodynamic patterns of meningococcal shock in children. Crit Care Med. 1988;16(1):27-33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198801000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramaswamy KN, Singhi S, Jayashree M, Bansal A, Nallasamy K. Double-blind randomized clinical trial comparing dopamine and epinephrine in pediatric fluid-refractory hypotensive septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(11):e502-e512. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ventura AM, Shieh HH, Bousso A, et al. Double-blind prospective randomized controlled trial of dopamine versus epinephrine as first-line vasoactive drugs in pediatric septic shock. crit care med. 2015;43(11):2292-2302. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chopra A, Kumar V, Dutta A. Hypertonic versus normal saline as initial fluid bolus in pediatric septic shock. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78(7):833-837. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0366-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yildizdas D, Yapicioglu H, Celik U, Sertdemir Y, Alhan E. Terlipressin as a rescue therapy for catecholamine-resistant septic shock in children. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(3):511-517. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0971-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santhanam I, Sangareddi S, Venkataraman S, Kissoon N, Thiruvengadamudayan V, Kasthuri RK. A prospective randomized controlled study of two fluid regimens in the initial management of septic shock in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(10):647-655. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818844cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Upadhyay M, Singhi S, Murlidharan J, Kaur N, Majumdar S. Randomized evaluation of fluid resuscitation with crystalloid (saline) and colloid (polymer from degraded gelatin in saline) in pediatric septic shock. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(3):223-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naveda OE, Naveda AF. Positive fluid balance and high mortality in paediatric patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Pediatria (Napoli). 2016;49(3):71-77. doi: 10.1016/j.rcpe.2016.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu JR, Chen IC, Dai ZK, Hung JF, Hsu JH. Early elevated B-type natriuretic peptide levels are associated with cardiac dysfunction and poor clinical outcome in pediatric septic patients. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2015;31(6):485-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bustos B R, Padilla P O. Valor predictivo de la procalcitonina en niños con sospecha de sepsis. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2015;86(5):331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cui Y, Zhang Y, Rong Q, Xu L, Zhu Y, Ren Y. A comparison of high versus standard-volume hemofiltration in critically ill children with severe sepsis [article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;95(5):353-358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen R, Zhang Y, Cui Y, Miao H, Xu L, Rong Q. Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide difference in critically ill pediatric patients with septic shock [article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014;52(12):918-922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ibrahiem SK, Galal YS, Youssef MRL, Sedrak AS, El Khateeb EM, Abdel-Hameed ND. Prognostic markers among Egyptian children with sepsis in the intensive care units, Cairo University hospitals. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2016;44(1):46-53. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Gong H, Wang Y, et al. A multicenter prospective clinical study on continuous blood purification in treating childhood severe sepsis [article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014;52(6):438-443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manzoli TF, Troster EJ, Ferranti JF, Sales MM. Prolonged suppression of monocytic human leukocyte antigen-DR expression correlates with mortality in pediatric septic patients in a pediatric tertiary Intensive Care Unit. J Crit Care. 2016;33:84-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rady H, Hafez M, Bazaraa H, Aly Y. Adrenocortical status in infants and children with sepsis and septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):185. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000449555.67146.f124492195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ranjit S, Natraj R, Kandath SK, Kissoon N, Ramakrishnan B, Marik PE. Early norepinephrine decreases fluid and ventilatory requirements in pediatric vasodilatory septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20(10):561-569. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.192036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Samransamruajkit R, Nakornchai K, Pongsanon K, Deerojanawong J, Sritippayawan S, Prapphal N. Interleukin-10 polymorphisms and clinical risk factors in children with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Shock. 2014;17(2):50-57. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuan YH, Yuan YH, Xiao ZH, et al. Impact of continuous blood purification on T cell subsets in children with severe sepsis [article in Chinese]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014;16(2):194-197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen J, Li X, Bai Z, et al. Association of fluid accumulation with clinical outcomes in critically ill children with severe sepsis. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0160093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phumeetham S, Chat-Uthai N, Manavathongchai M, Viprakasit V. Genetic association study of tumor necrosis factor-alpha with sepsis and septic shock in Thai pediatric patients. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2012;88(5):417-422. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jat KR, Jhamb U, Gupta VK. Serum lactate levels as the predictor of outcome in pediatric septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2011;15(2):102-107. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.83017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raj S, Killinger JS, Gonzalez JA, Lopez L. Myocardial dysfunction in pediatric septic shock. J Pediatr. 2014;164(1):72-77.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sankar J, Sankar MJ, Suresh CP, Dubey NK, Singh A. Early goal-directed therapy in pediatric septic shock: comparison of outcomes “with” and “without” intermittent superior venacaval oxygen saturation monitoring: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):e157-e167. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sankar J, Das RR, Jain A, et al. Prevalence and outcome of diastolic dysfunction in children with fluid refractory septic shock—a prospective observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(9):e370-e378. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karim F, Adil SN, Afaq B, Ul Haq A. Deficiency of ADAMTS-13 in pediatric patients with severe sepsis and impact on in-hospital mortality. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ranjit S, Aram G, Kissoon N, et al. Multimodal monitoring for hemodynamic categorization and management of pediatric septic shock: a pilot observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(1):e17-e26. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182a5589c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Samransamruajkit R, Uppala R, Pongsanon K, Deelodejanawong J, Sritippayawan S, Prapphal N. Clinical outcomes after utilizing surviving sepsis campaign in children with septic shock and prognostic value of initial plasma NT-proBNP. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18(2):70-76. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.126075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cartaya JM, Rovira LE, Segredo Y, Alvarez I, Acevedo Y, Moya A. Implementing ACCM critical care guidelines for septic shock management in a Cuban pediatric intensive care unit. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(3-4):47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu XJ, Tang YM, Song H, et al. A multiplex cytokine score for the prediction of disease severity in pediatric hematology/oncology patients with septic shock. Cytokine. 2013;64(2):590-596. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carmona F, Manso PH, Silveira VS, Cunha FQ, de Castro M, Carlotti AP. Inflammation, myocardial dysfunction, and mortality in children with septic shock: an observational study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35(3):463-470. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0801-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oliveira NS, Silva VR, Castelo JS, Elias-Neto J, Pereira FE, Carvalho WB. Serum level of cardiac troponin I in pediatric patients with sepsis or septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(4):414-417. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31817e2b33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Santolaya ME, Alvarez AM, Aviles CL, et al. Predictors of severe sepsis not clinically apparent during the first twenty-four hours of hospitalization in children with cancer, neutropenia, and fever: a prospective, multicenter trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(6):538-543. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181673c3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Onenli-Mungan N, Yildizdas D, Yapicioglu H, Topaloglu AK, Yüksel B, Ozer G. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 levels and their relation to survival in children with bacterial sepsis and septic shock. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40(4):221-226. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pancera CF, Costa CM, Hayashi M, Lamelas RG, Camargo Bd. Sepse grave e choque séptico em crianças com câncer: fatores preditores de óbito. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2004;50(4):439-443. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302004000400037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Samransamruajkit R, Hiranrat T, Prapphal N, Sritippayawan S, Deerojanawong J, Poovorawan Y. Levels of protein C activity and clinical factors in early phase of pediatric septic shock may be associated with the risk of death. Shock. 2007;28(5):518-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sarthi M, Lodha R, Vivekanandhan S, Arora NK. Adrenal status in children with septic shock using low-dose stimulation test. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(1):23-28. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000256622.63135.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Casartelli CH, Garcia PCR, Branco RG, Piva JP, Einloft PR, Tasker RC. Adrenal response in children with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1609-1613. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0699-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Branco RG, Garcia PC, Piva JP, Casartelli CH, Seibel V, Tasker RC. Glucose level and risk of mortality in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(4):470-472. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161284.96739.3A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pizarro CF, Troster EJ, Damiani D, Carcillo JA. Absolute and relative adrenal insufficiency in children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(4):855-859. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000159854.23324.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Singh D, Chopra A, Pooni PA, Bhatia RC. A clinical profile of shock in children in Punjab, India. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(7):619-623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goh A, Lum L. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock in paediatric multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(5):488-492. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.355409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lodha R, Vivekanandhan S, Sarthi M, Kabra SK. Serial circulating vasopressin levels in children with septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7(3):220-224. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000216414.00362.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Derkx B, Wittes J, McCloskey R; European Pediatric Meningococcal Septic Shock Trial Study Group . Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of HA-1A, a human monoclonal antibody to endotoxin, in children with meningococcal septic shock. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28(4):770-777. doi: 10.1086/515184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Leteurtre S, Leclerc F, Martinot A, et al. Can generic scores (Pediatric Risk of Mortality and Pediatric Index of Mortality) replace specific scores in predicting the outcome of presumed meningococcal septic shock in children? Crit Care Med. 2001;29(6):1239-1246. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200106000-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Goldfarb DM, Schlattmann P, Schlapbach LJ, Reinhart K, Kissoon N. The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(3):223-230. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30063-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, et al. Surviving Sepsis campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(4):536-555. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2210-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. ; International Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee; American Association of Critical-Care Nurses; American College of Chest Physicians; American College of Emergency Physicians; Canadian Critical Care Society; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; European Respiratory Society; International Sepsis Forum; Japanese Association for Acute Medicine; Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; Surgical Infection Society; World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine . Surviving Sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):296-327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. ; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee, including the Pediatric Subgroup . Surviving Sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165-228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock, 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486-552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wong JJ, Jit M, Sultana R, et al. Mortality in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;885066617705109:885066617705109. doi: 10.1177/0885066617705109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baelani I, Jochberger S, Laimer T, et al. Availability of critical care resources to treat patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in Africa: a self-reported, continent-wide survey of anaesthesia providers. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R10. doi: 10.1186/cc9410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rao NDPS. Energy access and living standards: some observations on recent trends. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:025011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa5b0d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schultz MJ, Dunser MW, Dondorp AM, et al. ; Global Intensive Care Working Group of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine . Current challenges in the management of sepsis in ICUs in resource-poor settings and suggestions for the future. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(5):612-624. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4750-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wiens MO, Pawluk S, Kissoon N, et al. Pediatric post-discharge mortality in resource poor countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search strategies for databases

eTable 2. Characteristics of included studies conducted in developed countries

eTable 3. Characteristics of included studies conducted in developing countries

eTable 4. Risk of bias of individual randomized controlled trials

eTable 5. Risk of bias of individual observational studies

eFigure 1. Cumulative forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies conducted in developed countries

eFigure 2. Cumulative forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies conducted in developing countries

eFigure 3. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from randomized controlled trials

eFigure 4. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from observational studies

eFigure 5. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies with severe sepsis populations

eFigure 6. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from studies with septic shock populations

eFigure 7. Forest plot of case-fatality rates from high quality studies with low risk of bias

eFigure 8. Time-trend of pooled weighted mortality rates from 1982 to 2016 (by year of study) for high-quality studies with low risk of bias