Key Points

Question

Is cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder a more efficacious treatment than supportive psychotherapy for reducing body dysmorphic disorder symptom severity?

Findings

In this 2-site randomized clinical trial of 120 adults with primary body dysmorphic disorder, the difference in the efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder and supportive psychotherapy was site specific. The 2 treatments were comparable at 1 site, but cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder achieved statistically significantly better results at the other site.

Meaning

Both treatments improved body dysmorphic disorder severity; however, cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder reduced symptom severity more consistently across the 2 sites.

Abstract

Importance

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the best-studied treatment for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), has to date not been compared with therapist-delivered supportive psychotherapy, the most commonly received psychosocial treatment for BDD.

Objective

To determine whether CBT for BDD (CBT-BDD) is superior to supportive psychotherapy in reducing BDD symptom severity and associated BDD-related insight, depressive symptoms, functional impairment, and quality of life, and whether these effects are durable.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital and Rhode Island Hospital recruited adults with BDD between October 24, 2011, and July 7, 2016. Participants (n = 120) were randomized to the CBT-BDD arm (n = 61) or the supportive psychotherapy arm (n = 59). Weekly treatments were administered at either hospital for 24 weeks, followed by 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Measures were administered by blinded independent raters. Intention-to-treat statistical analyses were performed from February 9, 2017, to September 22, 2018.

Interventions

Cognitive behavioral therapy for BDD, a modular skills–based treatment, addresses the unique symptoms of the disorder. Supportive psychotherapy is a nondirective therapy that emphasizes the therapeutic relationship and self-esteem; supportive psychotherapy was enhanced with BDD-specific psychoeducation and treatment rationale.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was BDD symptom severity measured by the change in score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD from baseline to end of treatment. Secondary outcomes were the associated symptoms and these were assessed using the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale, Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition, Sheehan Disability Scale, and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form.

Results

Of the 120 participants, 92 (76.7%) were women, with a mean (SD) age of 34.0 (13.1) years. The difference in effectiveness between CBT-BDD and supportive psychotherapy was site specific: at 1 site, no difference was detected (estimated mean [SE] slopes, –18.6 [1.9] vs –16.7 [1.9]; P = .48; d growth-modeling analysis change, –0.25), whereas at the other site, CBT-BDD led to greater reductions in BDD symptom severity, compared with supportive psychotherapy (estimated mean [SE] slopes, –18.6 [2.2] vs –7.6 [2.0]; P < .001; d growth-modeling analysis change, –1.36). No posttreatment symptom changes were observed throughout the 6 -months of follow-up (all slope P ≥ .10).

Conclusions and Relevance

Body dysmorphic disorder severity and associated symptoms appeared to improve with both CBT-BDD and supportive psychotherapy, although CBT-BDD was associated with more consistent improvement in symptom severity and quality of life.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01453439

This randomized clinical trial compares the symptom reduction and treatment gain durability between cognitive behavioral therapy or supportive psychotherapy for adults with body dysmorphic disorder.

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a common, often severe, disorder affecting 1.7% to 2.9% of the general population.1,2,3,4,5 It is associated with substantial impairment and high rates of hospitalization and suicidality.6,7 Six randomized clinical trials8,9,10,11,12,13 have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for BDD in adults (response rates, 48%-82%). Of relevance to this report, a trial found that 12 weeks of internet-based CBT was superior to internet-based supportive psychotherapy for BDD after treatment (54% vs 6% responders) and at 3 months after treatment (56% vs 3% responders).13

However, previous trials of CBT for BDD were limited by small, restrictive samples. Only 2 studies10,12 used published treatment manuals, and only 1 study12 included specific modular strategies to target BDD symptoms that some but not all patients experience. Only 2 trials10,13 used an active comparison treatment (anxiety management vs online supportive psychotherapy) to control for therapist attention and other nonspecific treatment factors. However, neither of these comparison treatments are routinely used to treat BDD in the community. Therapist-delivered supportive psychotherapy is the psychosocial treatment most commonly received by individuals with BDD,14 yet its efficacy for this disorder has never been tested.

We report on, to our knowledge, the largest BDD treatment study and the largest randomized clinical trial of CBT for BDD. Participants were randomized to CBT for BDD (CBT-BDD) or to supportive psychotherapy for 24 weeks, followed by 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. The primary aim was to test the efficacy of CBT-BDD in comparison to supportive psychotherapy. We hypothesized that BDD symptoms, BDD-related insight, depressive symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life would improve significantly over the 24 weeks of therapy, with greater posttreatment effects for CBT than for supportive psychotherapy. We also hypothesized that treatment gains would be more durable (ie, maintained throughout 6 months of follow-up) for CBT-BDD.

Method

The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Rhode Island Hospital (RIH). Participants provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring board provided oversight. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Participants

Participants were recruited between October 24, 2011, and July 7, 2016, at MGH and RIH (eMethods in Supplement 2). Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older; primary diagnosis of BDD according to the DSM-IV; and a score of 24 or higher on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS),15 which corresponds to moderate severity15 and is a commonly used cut point for BDD treatment studies10,12,16 (BDD-YBOCS score range: 0-48, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity). Exclusion criteria were current suicidality, need for a higher level of care (according to screening procedures and clinician judgment), cognitive impairment (eg, estimated IQ of <80 on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence17), current substance use disorder, current mania, psychosis, borderline personality disorder, body image concerns primarily accounted for by an eating disorder, behavior or medical illness that would interfere with participation, history of 10 or more CBT sessions for BDD, or concurrent psychotherapy. Psychotropic medication was allowed if the dose was stable for 2 or more months before study intake and the patient agreed not to change medication during the study.

Study Design and Procedures

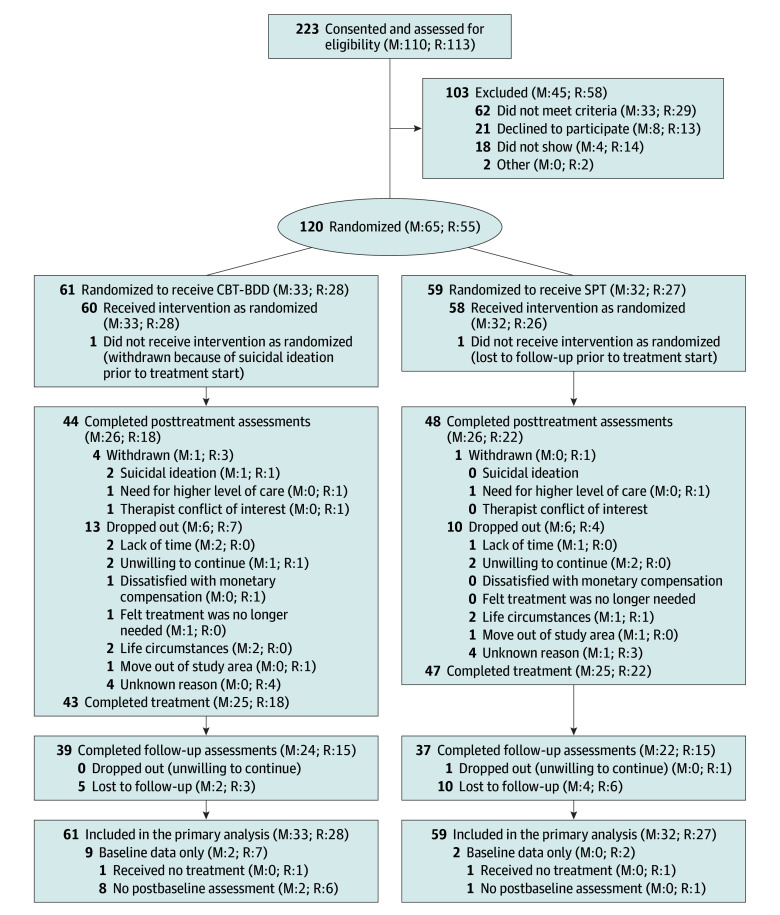

Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to either CBT-BDD or supportive psychotherapy. Randomization was stratified by site and used a randomly interspersed mixture of blocks of 2 and 4 participants to achieve a balanced treatment assignment throughout the study and maintain blindness to treatment allocation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through the Trial.

Treatment completers were participants who completed 24 weeks of treatment regardless of whether they missed sessions or not. Site-specific numbers are provided at the end of each category. CBT-BDD indicates cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder; M, Massachusetts General Hospital; R, Rhode Island Hospital; and SPT, supportive psychotherapy.

Treatments

Both treatments consisted of 22 individual 60-minute sessions for 24 weeks, based on the empirically tested CBT-BDD manual12,18,19 and matched in length and number of sessions for supportive psychotherapy. Sessions were weekly, except for the last 2 sessions, which were spaced 2 weeks apart. Participants who responded to either treatment by week 24 (≥30% reduction in BDD-YBOCS score) received 2 booster sessions, at 1 and 3 months after treatment.

Treatments, therapists, and fidelity are described in the eMethods in Supplement 2. To avoid allegiance effects, therapists provided only the treatment for which they were qualified. Supportive psychotherapy therapists at MGH were somewhat more educated, experienced, and competent, but global treatment adherence and competence were excellent for both treatment conditions at both sites (eMethods and eResults in Supplement 2).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Cognitive behavioral therapy for BDD19 is based on a neurobiologically informed20,21,22 cognitive behavioral model of BDD. This treatment consists of psychoeducation; case formulation; setting valued goals; motivational enhancement; cognitive restructuring; exposure and ritual prevention; mindfulness and attentional retraining; and advanced strategies to modify self-defeating assumptions about the importance of appearance and to enhance self-acceptance, self-esteem, and self-compassion. Optional modules target symptoms (eg, seeking surgical intervention) that require specific strategies. All patients received relapse prevention (final 2 sessions) to help them prevent and react effectively to setbacks.

Supportive Psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy23,24 focuses on maintaining, improving, and restoring self-esteem and adaptive coping skills as well as on reflecting and expressing emotions about current life issues. The intent of this nondirective treatment is to help patients learn to cope with external and psychological challenges,23,24 emphasizing the therapeutic relationship and self-esteem as vehicles for patient improvement. A supportive psychotherapy manual23 was enhanced with BDD-specific psychoeducation and treatment rationale to enhance treatment engagement, quality, and credibility.

Assessments

Clinician-administered measures were administered by master’s- or doctoral-level independent evaluators, who were blinded to treatment. Independent evaluators’ training, fidelity, and blinding procedures are detailed in the eMethods in Supplement 2. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders25 and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders26 were used to determine inclusion and exclusion diagnoses and baseline comorbidity. Demographic data were collected via self-report at baseline (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Symptom severity of BDD, the primary outcome, was assessed with the clinician-administered BDD-YBOCS.15 Secondary outcomes were assessed using the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale27 for BDD-related insight (total score range: 0-24, with higher scores indicating poorer insight about symptoms), Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition28 for depressive symptom severity (total score range: 0-63, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity), Sheehan Disability Scale29 for functional impairment (score range: 0-30, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment), and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form30 for quality of life (score range: 0%-100%, with higher scores indicating greater quality of life). We assessed patients’ beliefs about the credibility and expected outcome of the treatment using the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire31,32 and treatment satisfaction using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8.33 Measures were administered monthly during treatment and at 3- and 6-month follow-up, except for the Sheehan Disability Scale and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (administered at weeks 0, 4, 12, 16, and 24, and then at 3- and 6-month follow-up), Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (weeks 0 and 4), and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (weeks 12 and 24). Adverse events were assessed monthly and rated for severity, action taken, outcome, and association with treatment (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Statistical Analysis

Intention-to-treat statistical analyses that used all available data from all randomized participants were performed from February 9, 2017, to September 22, 2018. Baseline differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between sites were analyzed using unpaired, 2-tailed t tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The primary outcome (BDD-YBOCS change during weeks 0-24) was analyzed using a linear latent growth curve modeling approach, which accounted for site but not treatment differences at baseline,34 site effects over time, and treatment-by-site interactions over time and used random intercepts and slopes with an unstructured covariance matrix to account for repeated measures. Degrees of freedom were estimated using the Kenward-Roger method. Model residuals did not indicate any departures from normality and showed homogeneity of variance. Effect sizes of slopes over time were calculated as d growth-modeling analysis change = βtx/(τ)1/2, in which βtx was the difference between treatment-specific slope estimates and τ was the within-group variance of the slopes35; these effect sizes can be interpreted in the same way as Cohen d. Statistical significance was evaluated at a 2-tailed P < .05. Effect estimates of slopes and slope differences are presented as model-adjusted least square means with SEs. For descriptive purposes, treatment response (≥30% reduction in BDD-YBOCS scores15 from baseline to week 24) was calculated on the basis of the observed status of end-of-treatment assessment completers only. The secondary outcome latent growth curve modeling analysis of BDD-YBOCS change during follow-up (weeks 24-50) also included treatment and treatment-by-site effects to allow for different intercepts at week 24. Secondary outcomes (ie, Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale, Sheehan Disability Scale, and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form) used the same modeling approach and were not adjusted for multiple tests.36

The exploratory outcomes of the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance models with treatment-by-site interactions. Effect sizes for differences between treatment means at a given assessment were reported as Cohen d, using pooled SDs. Differences in the probability of dropout during treatment were assessed with a survival analysis using log-rank tests to find the differences between treatment-by-site strata, followed by proportional hazards models to assess risk factors for dropout (eFigure in Supplement 2). All analyses were performed using SAS System for Windows, version 9.4 (IBM).

The study was powered a priori to detect a difference of 4.4 points on the 48-point BDD-YBOCS after 24 weeks of treatment (ie, 0.18 point per week; primary outcome), assuming a 2-sided α = .05, 80% power, dropout rate of 20%, no site effects, a variance-covariance estimate based on a previous pilot study,12 and a sample size of 120 participants. The power calculations were performed using the R package LPower (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).37 The minimum detectable difference of 4.4 points was chosen on the basis of a clinically meaningful effect size relevance and recruitment feasibility.

Results

Enrollment and Sample Description

Across both sites, 223 participants were enrolled, of whom 103 were ineligible and 120 were randomized to treatment. Of the 120 participants, 61 (50.8%) were randomized to CBT-BDD, and 59 (49.2%) to supportive psychotherapy; 65 participants were treated at MGH and 55 at RIH (Figure 1). Participants were predominantly women (92 [76.7%) and non-Hispanic white individuals (100 [83.3%]), with a mean (SD) age of 34.0 (13.1) years. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics by site. We detected no statistically significant baseline site differences in primary or secondary outcome variables. Participants at MGH, compared with those in RIH, were more educated (college graduates: 27 [41.5%] vs 11 [20.0%]; P = .02), had a higher prevalence of avoidant personality disorder (39 [60.0%] vs 15 [27.3%]; P < .001), and were less likely to be taking benzodiazepines (6 [9.4%] vs 13 [23.6%]; P = .04).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Randomized Participants.

| Variable | MGH (n = 65)a | RIH (n = 55) | Site Difference P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographicsc | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 32.2 (12.8) | 36.0 (13.1) | .11 |

| Male, No. (%) | 19 (29.2) | 9 (16.4) | .10 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | .12 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 52 (80.0) | 48 (87.3) | |

| White, Hispanic | 3 (4.6) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Black | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 (9.2) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Other | 2 (3.1) | 5 (9.1) | |

| Education, No. (%) | .04 | ||

| ≤High school graduate | 6 (9.2) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Technical school/some college | 14 (21.5) | 18 (32.7) | |

| College graduate | 27 (41.5) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Graduate or professional school | 18 (27.7) | 15 (27.3) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | .13 | ||

| Single, never married | 43 (66.2) | 30 (54.5) | |

| Married | 8 (12.3) | 15 (27.3) | |

| Other | 14 (21.5) | 10 (18.2) | |

| Employment, No. (%) | .48 | ||

| Full-time (≥35 h/wk) | 29 (44.6) | 17 (30.9) | |

| Part-time (<35 h/wk) | 15 (23.1) | 12 (21.8) | |

| Student | 7 (10.8) | 7 (12.7) | |

| Unemployed | 9 (13.8) | 13 (23.6) | |

| Other | 5 (7.7) | 6 (10.9) | |

| Current psychiatric comorbidities | |||

| DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses (>5% prevalence), No. (%)d | |||

| Social anxiety disorder | 26 (40.0) | 18 (32.7) | .45 |

| Major depressive disorder | 19 (29.7) | 20 (36.4) | .56 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 18 (27.7) | 14 (25.5) | .84 |

| Specific phobia | 12 (18.5) | 5 (9.1) | .19 |

| Dysthymia | 10 (15.4) | 5 (9.1) | .41 |

| Excoriation (skin picking) disorder | 8 (12.3) | 7 (12.7) | >.99 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 11 (16.9) | 4 (7.3) | .17 |

| Panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) | 8 (12.3) | 4 (7.3) | .54 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 7 (10.8) | 5 (9.1) | >.99 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 7 (10.8) | 4 (7.3) | .55 |

| Olfactory reference syndrome | 5 (7.7) | 3 (5.5) | .73 |

| Other Axis I diagnosise | 12 (18.5) | 9 (16.5) | .81 |

| DSM-IV Axis II diagnoses (>5% prevalence), No. (%)d | |||

| Avoidant personality disorder | 39 (60.0) | 15 (27.3) | <.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 16 (24.6) | 7 (12.7) | .11 |

| Paranoid personality disorder | 9 (13.8) | 5 (9.1) | .57 |

| Dependent personality disorder | 6 (9.2) | 1 (1.8) | .12 |

| Other Axis II diagnosisf | 5 (7.7) | 3 (5.5) | .73 |

| Current psychotropic medication, No. (%)d | |||

| None | 40 (61.5) | 25 (45.5) | .10 |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 17 (26.6) | 14 (25.5) | >.99 |

| Benzodiazepine | 6 (9.4) | 13 (23.6) | .04 |

| Non-SRI antidepressant | 6 (9.4) | 11 (20.0) | .12 |

| Anticonvulsant | 4 (6.3) | 6 (10.9) | .51 |

| Antipsychotic | 1 (1.6) | 5 (9.1) | .09 |

| Other psychotropic medication | 8 (12.5) | 9 (16.5) | .61 |

| Clinical characteristics, mean (SD) | |||

| BDD-YBOCS total score | 32.6 (5.0) | 31.0 (4.5) | .07 |

| BABS total score | 16.4 (4.2) | 16.3 (4.5) | .94 |

| BDI-II total score | 21.9 (13.1) | 21.2 (12.1) | .76 |

| SDS total score | 17.2 (5.4) | 16.5 (6.3) | .52 |

| QLESQ-SF percentage score | 51.9 (15.0) | 47.2 (16.5) | .11 |

Abbreviations: BABS, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (total score range: 0-24, with higher scores indicating poorer insight about symptoms; mean scores are in the poor insight range); BDD, body dysmorphic disorder; BDD-YBOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD (score range: 0-48, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity); BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (total score range: 0-63, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity); MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; QLESQ-SF, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (score range: 0%-100%, with higher scores indicating greater quality of life); RIH, Rhode Island Hospital; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (score range: 0-30, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment); SRI, serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Missing data: MDD diagnosis (MGH n = 1), all psychotropic medication categories other than “none” (MGH n = 1).

Site differences were evaluated with a 2-sample, unpaired, 2-tailed t test for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables.

Percentages for race/ethnicity, education, and employment do not add to 100 in all cases because of rounding.

Percentages for Axis I diagnoses, Axis II diagnoses, and current psychotropic medication may add up to more than 100% because participants could have multiple comorbidities or medications.

Other diagnosis includes bipolar I disorder (n = 1), agoraphobia without panic disorder (n = 4), pain disorder (n = 2), undifferentiated somatoform disorder (n = 1), hypochondriasis (n = 3), anorexia (n = 1), eating disorder not otherwise specified (n = 9), or chronic motor tic disorder (n = 2). Some participants had more than 1 other Axis I diagnosis.

Other diagnosis includes schizotypal (n = 2), schizoid (n = 1), narcissistic (n = 2), antisocial (n = 3), or not otherwise specified (n = 1) personality disorder. Some participants had more than 1 other Axis II diagnosis.

Efficacy of Treatment for Symptom Severity

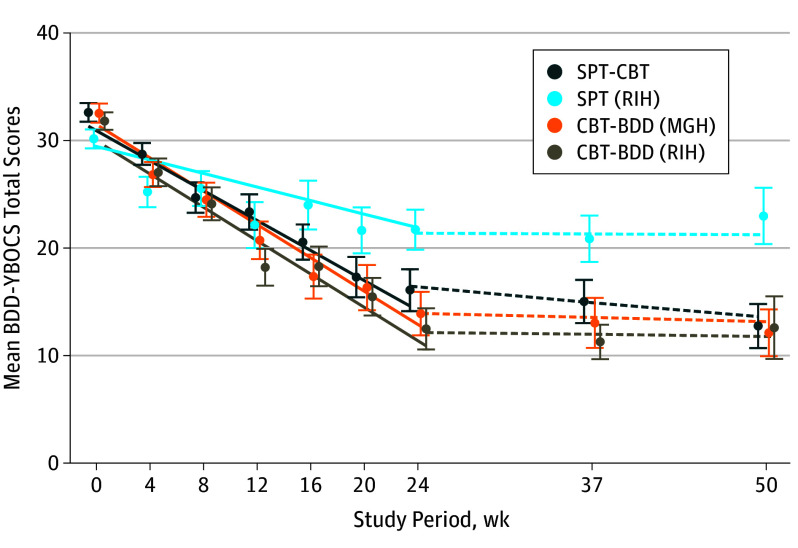

The severity of BDD (BDD-YBOCS) decreased statistically significantly throughout treatment in both arms and at both sites, although the rate of decrease differed by treatment and site (Table 2). In testing our original null hypothesis, which anticipated no site differences, we found that BDD symptoms decreased statistically significantly more in CBT-BDD than in supportive psychotherapy by the end of treatment (estimated mean [SE] slopes, –18.6 [1.4] vs –12.1 [1.4]; time-by-treatment estimate, −6.46 [95% CI, −10.43 to −2.49]; P = .002; d growth-modeling analysis change, –0.76; Table 2). However, a statistically significant time-by-treatment-by-site interaction (time × treatment × site estimated difference in treatment slope differences, 4.58 [95% CI, 0.6-8.6]; P = .02) indicated that the treatment difference was only significant at RIH, in which the estimated mean (SE) slopes of BDD-YBOCS scores were –18.6 (2.2) over 24 weeks for CBT-BDD and –7.6 (2.0) for supportive psychotherapy (estimated mean slope difference, –11.0 [95% CI, −17.0 to −5.1]; P < .001; d growth-modeling analysis change, –1.36). By contrast, treatment differences were minimal at MGH, in which the estimated mean (SE) slopes of BDD-YBOCS scores were –18.6 (1.9) over 24 weeks for CBT-BDD and –16.7 (1.9) for supportive psychotherapy (estimated mean slope difference, –1.9 [95% CI, −7.1 to 3.4]; time × treatment × site, P = .48; d growth-modeling analysis change, –0.25; Figure 2). Thus, the treatment efficacy advantage of CBT-BDD over supportive psychotherapy was site specific, ranging from a strong effect at RIH to a nonsignificant, nominal effect at MGH. Overall response rates for assessment completers at week 24 were 84.6% (22 of 26) at MGH and 83.3% (15 of 18) at RIH for CBT-BDD, and 69.2% (18 of 26) at MGH and 45.5% (10 of 22) at RIH for supportive psychotherapy.

Table 2. Tests of Intercept Differences, Overall Slope Effects, and Slope Differences in Random Intercept Random Coefficient Models of Primary and Secondary Treatment Outcomes During Treatment .

| Outcome and Effect | Effect Typea | Estimate (95% CI)b | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||

| BDD symptom severity (BDD-YBOCS) | |||

| Site | Intercept difference | 1.81 (−0.11 to 3.73) | .06 |

| Time | Overall changec | −15.37 (−17.36 to −13.38) | <.001 |

| Time × treatment | Effect of treatment overallc | −6.46 (−10.43 to −2.49) | .002 |

| Time × site | Effect of site overallc | −4.57 (−8.55 to −0.60) | .02 |

| Time × treatment × site | Site difference in treatment effectc | 4.58 (0.62 to 8.55) | .02 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Insight (BABS) | |||

| Site | Intercept difference | −0.02 (−1.75 to 1.70) | .98 |

| Time | Overall changec | −7.91 (−9.19 to −6.64) | <.001 |

| Time × treatment | Effect of treatment overallc | −2.07 (−4.55 to 0.41) | .10 |

| Time × site | Effect of site overallc | −1.18 (−3.73 to 1.37) | .36 |

| Time × treatment × site | Site difference in treatment effectc | 2.23 (−0.25 to 4.71) | .08 |

| Depression severity (BDI-II) | |||

| Site | Intercept difference | 0.42 (−4.25 to 5.08) | .86 |

| Time | Overall changec | −8.10 (−10.43 to −5.78) | <.001 |

| Time × treatment | Effect of treatment overallc | −4.48 (−8.97 to 0.00) | .05 |

| Time × site | Effect of site overallc | −0.10 (−4.75 to 4.56) | .97 |

| Time × treatment × site | Site difference in treatment effectc | 2.25 (−2.24 to 6.73) | .32 |

| Functional impairment (SDS) | |||

| Site | Intercept difference | 0.8 (−1.29 to 2.90) | .45 |

| Time | Overall changec | −8.07 (−9.80 to −6.34) | <.001 |

| Time × treatment | Effect of treatment overallc | −1.75 (−5.10 to 1.59) | .30 |

| Time × site | Effect of site overallc | −1.71 (−5.18 to 1.75) | .33 |

| Time × treatment × site | Site difference in treatment effectc | 2.08 (−1.27 to 5.42) | .22 |

| Quality of life (QLESQ-SF), % | |||

| Site | Intercept difference | 5.43 (−0.16 to 11.03) | .06 |

| Time | Overall changec | 16.30 (12.82 to 19.79) | <.01 |

| Time × treatment | Effect of treatment overallc | 7.20 (0.35 to 14.05) | .04 |

| Time × site | Effect of site overallc | 1.48 (−5.49 to 8.46) | .67 |

| Time × treatment × site | Site difference in treatment effectc | −5.58 (−12.44 to 1.27) | .11 |

Abbreviations: BABS, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (total score range: 0-24, with higher scores indicating poorer insight about symptoms); BDD, body dysmorphic disorder; BDD-YBOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD (score range: 0-48, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity); BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (total score range: 0-63, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity); QLESQ-SF, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short form (score range: 0%-100%, with higher scores indicating greater quality of life); SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale global functioning score (score range: 0-30, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment).

Effect type refers to the model parameters tested in the latent growth curve models, where site tests are differences in mean intercepts at week 0, time tests are the overall mean slope over the time period indicated, and time × treatment, time × site, and time × treatment × site test are mean slope differences between treatments, sites, or treatments within each site.

Units are scale points on each scale except for the QLESQ-SF, where the units are percentage score points.

Change is over 24 weeks of assessment during treatment. Any effect where P < .05 is a significant effect that is explained in the Statistical Analysis subsection.

Figure 2. Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptom Severity Over Time by Treatment and Site.

The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS) mean scores decreased over time in the supportive psychotherapy (SPT) and cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder (CBT-BDD) treatment arms from baseline to end of treatment (solid lines) and remained relatively unchanged during follow-up (dashed lines). Symptom severity of BDD decreased more in the CBT-BDD than supportive psychotherapy treatment arm at Rhode Island Hospital (RIH), but not at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). The lines shown are the model-based estimates of change over time in each treatment by site group, whereas the data points represent the raw means (SEs) of all available observations in each group at each time point. The data points based on raw data and the model-based linear trend estimates were offset from the actual week numbers in the graph to enable the visual discrimination of individual SE bars.

Effect of Treatment on Secondary Symptoms and Durability of Treatment Gains

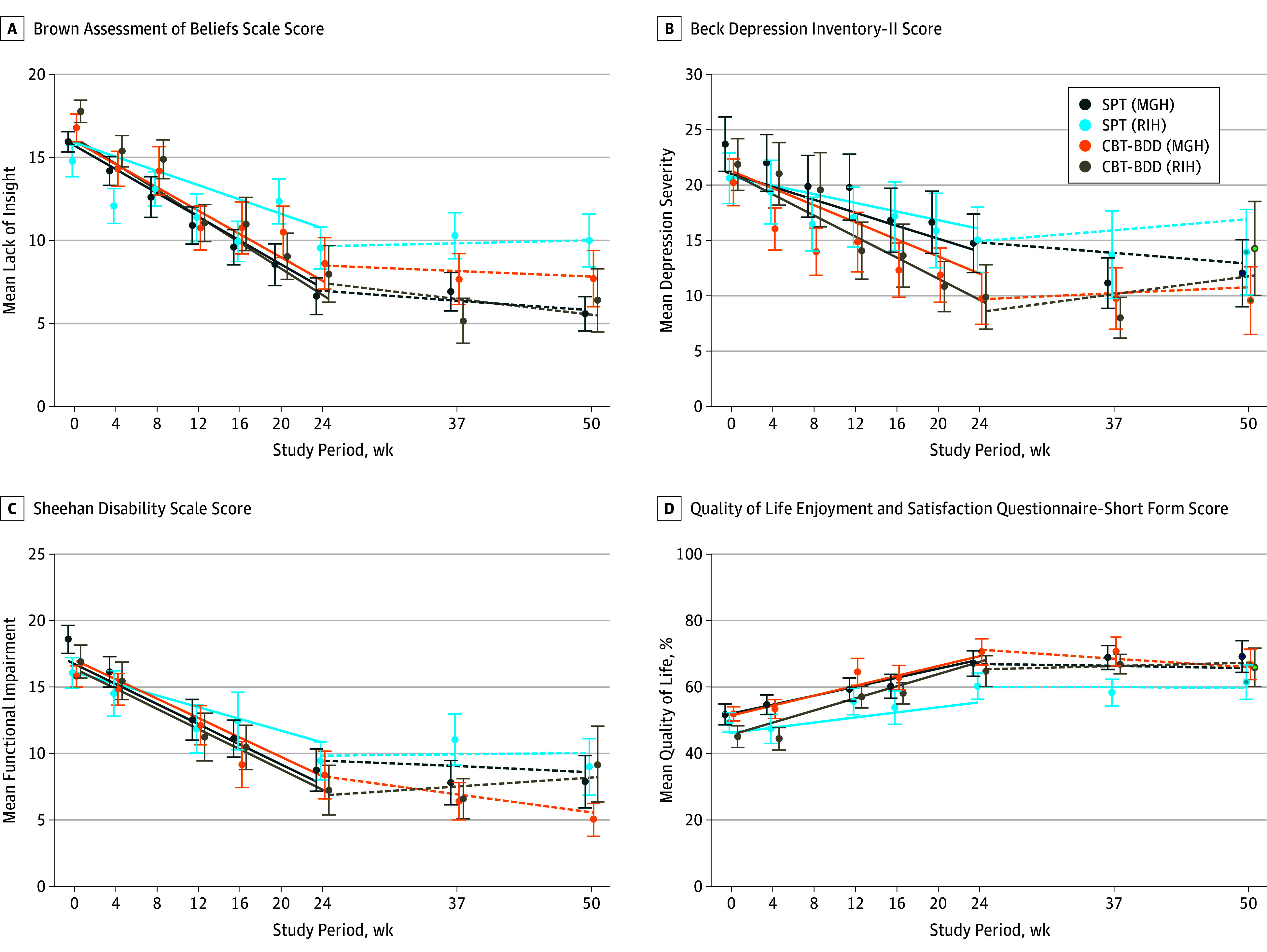

Depressive symptoms, BDD-related insight, quality of life, and functional impairment improved in both conditions from baseline to week 24 (Figure 3), but the change in quality-of-life scores was statistically significantly greater for CBT-BDD than for supportive psychotherapy (estimated mean [SE] slopes, 19.9 [2.5] vs 12.7 [2.4]; time × treatment estimate, 7.20 [95% CI, 0.35-14.05]; P = .04; d growth-modeling analysis change, 0.57; Table 2). This difference appeared to be site specific as well (MGH estimated mean slope difference, 1.6 [95% CI, −7.6 to 10.8]; MGH d growth-modeling analysis change, 0.19 vs RIH estimated mean slope difference, 12.8 [95% CI, 2.6-23.0]; RIH d growth-modeling analysis change, 1.21), even though we were not able to detect a significant treatment-by-site slope interaction (time × treatment × site estimated difference in treatment slope differences, −5.6 [95% CI, −12.4 to 1.3]). We could detect no statistically significant treatment, site, or treatment-by-site differences with regard to depression severity, functional impairment, or BDD-related insight (Table 2).

Figure 3. Secondary Symptoms and Quality of Life Over Time by Treatment.

All secondary symptoms (A-C) decreased from baseline to week 24 in supportive psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder (CBT-BDD) treatment arms, whereas quality of life increased (D). No treatment or site differences were found in the rate of change of lack of insight (Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale score) and functional impairment (Sheehan Disability Scale) during treatment or follow-up. However, quality of life (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form) improved more in the CBT-BDD than the supportive psychotherapy treatment arm. No treatment or site differences were found in the rate of change in depression symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II [Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition]) during treatment; however, participants in the CBT-BDD arm who completed end-of-treatment assessments (week 24) were significantly less depressed than participants in the supportive psychotherapy arm. No significant changes were observed in secondary symptoms or quality of life during follow-up (weeks 24 to 50). The solid lines (estimated slopes from the growth models of change during treatment) and dashed lines (estimated slopes from the growth models of change during follow-up) shown are the model-based estimates of change over time in each treatment by site group, whereas the data points represent the raw means (SEs) of all available observations in each group at each time point. The data points based on raw data and the model-based linear trend estimates were offset from the actual week numbers in the graph to enable the visual discrimination of individual SE bars. MGH indicates Massachusetts General Hospital; RIH, Rhode Island Hospital.

We could detect no statistically significant differences in the slopes of BDD severity or any secondary clinical outcomes between CBT-BDD and supportive psychotherapy during the 6-month follow-up (all time effects of P ≥ .10; eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Attendance and Dropouts

Of the 120 randomized participants, 44 (72.1%) of 61 patients in the CBT-BDD arm and 48 (81.4%) of 59 of patients in the supportive psychotherapy arm completed the week 24 posttreatment assessment (Figure 1). At MGH, the dropout rate from therapy was nearly equal across both treatments (22% supportive psychotherapy vs 24% CBT-BDD; χ2 = 0.06; P = .81). At RIH, the dropout rate was less balanced, although we were not able to detect a statistically significant difference between treatments (19% supportive psychotherapy vs 36% CBT-BDD; χ2 = 2.55; P = .11). Most dropouts (7 [25.0%] of 28) in the CBT-BDD treatment arm at RIH occurred before the first independent evaluator assessment (eFigure in Supplement 2). Completers attended a mean (SD) number of 21.1 (2.0) CBT-BDD sessions and 20.5 (2.2) supportive psychotherapy sessions, whereas early terminators attended a mean (SD) number of only 5.4 (4.9) CBT-BDD sessions and 6.7 (5.1) supportive psychotherapy sessions. We were unable to detect any significant effects of baseline risk factors for therapy dropout after adjusting for multiple tests (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Figure 1 lists the withdrawal and dropout reasons. The 6-month primary outcome assessments were completed by 39 participants (63.9%) in the CBT-BDD arm and 37 participants (62.7%) in the supportive psychotherapy arm.

Treatment Satisfaction, Expectancy, and Credibility

Treatment satisfaction was substantially greater with participants in the CBT-BDD arm than those in the supportive psychotherapy arm at RIH (mean [SD], 28.5 [3.1] vs 25.7 [3.8]; P = .007; Cohen d, 0.81), although not at MGH (mean [SD], 28.9 [3.4] vs 28.3 [3.7]; P = .72; Cohen d, 0.15). Even prior to treatment, participants perceived the credibility of CBT-BDD treatment as higher than that of supportive psychotherapy at RIH (mean [SD], 6.7 [1.6] vs 5.3 [1.8]; P < .007; Cohen d, 0.80), but not at MGH (mean [SD], 6.2 [1.6] vs 6.6 [1.3]; P = .30; Cohen d, 0.26). In addition, participants expected greater improvement from CBT-BDD therapy at RIH (mean [SD], 60.0 [20.2] vs 46.7 [23.0]; P = .04; Cohen d, 0.62), but not at MGH (mean [SD], 57.0 [21.4] vs 53.0 [15.6]; P = .55, Cohen d, 0.21).

Adverse Events

Overall, 4 (6.8%) of 59 participants in the supportive psychotherapy arm and 2 (3.3%) of 61 participants in the CBT-BDD arm reported 1 or more adverse events that were possibly associated with study treatment. These reported events were increased depression (CBT-BDD: 1; supportive psychotherapy: 3), increased anxiety (CBT-BDD: 1; supportive psychotherapy: 1), and increased obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms (supportive psychotherapy: 2). No serious adverse events (eg, suicide attempts) occurred.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this trial is the first comparative study of therapist-delivered CBT-BDD and supportive psychotherapy. In this trial, we found that the treatment differences in the primary outcome, BDD symptom severity change, were site specific. Across the 2 sites, CBT-BDD was more consistently efficacious in reducing BDD-symptom severity, whereas the outcome was more variable with supportive psychotherapy. Changes in secondary symptoms mirrored those observed in BDD severity, although most were not statistically significant.

Participants in the CBT-BDD arm performed well at both sites, consistent with results in previous smaller studies.8,9,10,11,12,13 The proportion of responders (84.6% at MGH and 83.3% at RIH among completers) is somewhat higher than in most trials of briefer (ie, 8-16 sessions) duration (48%-78% of completers responded),9,10,11 suggesting that longer treatment may be more efficacious.10,12,38

The supportive psychotherapy response rate (69.2% at MGH and 45.5% at RIH among completers) exceeds that in anxiety disorders39,40,41,42,43 and is much higher than the rate in a 12-week trial of internet-based CBT (54%) vs supportive psychotherapy (6%) for BDD.13 The supportive psychotherapy response rates in the current randomized clinical trial differed considerably across sites, with differences emerging after week 12. It is unclear why improvement in supportive psychotherapy at RIH leveled off between weeks 12 and 24. No major changes to personnel, fidelity, or patient participation occurred. It is possible that, by week 12, patients had achieved most of the improvements they were going to achieve with the supportive psychotherapy delivered at RIH and that therapist factors at MGH (eg, somewhat more educated; see eMethods in Supplement 2) contributed to the continued improvement and greater participant satisfaction at MGH. Notably, MGH offers predoctoral and postdoctoral training in supportive or integrative psychotherapy; thus, supportive psychotherapy at MGH is likely superior to that offered in other academic medical or community settings (including RIH).

Common factors (eg, making a patient feel understood) and behaviors that could serve indirectly as exposure, such as repeatedly meeting with a therapist, may have decreased BDD-associated anxiety and likely enabled patients in either treatment to develop more adaptive beliefs. However, CBT and supportive psychotherapy likely also work via different specific mechanisms.44 If CBT achieves outcomes primarily through active components (ie, skills), and those components are delivered as intended, then common factors (eg, empathy, alliance) should have less bearing on the outcomes. Because supportive psychotherapy primarily emphasizes common factors, therapist factors may have had a greater effect on treatment, leading to more variable outcomes.45 Similarly, in a large, multisite panic disorder randomized clinical trial, relaxation training and psychodynamic psychotherapy had site differences, whereas CBT did not.46

Differences in perceived treatment credibility may have contributed to the site difference in the supportive psychotherapy treatment response. To optimize treatment outcome, future studies might consider assessing and, if necessary, enhancing treatment credibility through education.

Secondary symptoms (BDD-related insight, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment) improved in both treatments, and we found no evidence of any differential treatment effect on treatments. Quality of life also improved, but it was the only secondary symptom that differed between treatments, and again only at RIH. Symptom improvement was maintained throughout the 6-month follow-up, regardless of treatment type. These findings support previous research on CBT’s durability38 and influence on secondary symptoms10,12,13 and indicate that supportive psychotherapy has a similarly durable effect.

Both treatments were well tolerated. Adverse events were minimal. These findings are notable in that an oft-cited barrier to providing CBT is the belief that patients cannot tolerate anxiety-provoking exposures.47

Strengths and Limitations

This study’s strengths include being a 2-site randomized clinical trial with blinded assessments, the high-quality treatment delivered only by therapists uniquely qualified for the specific condition they were treating, analysis by intention to treat, and use of repeated measures per participant over time to increase measure sensitivity to individual differences and reliability. To our knowledge, only a few controlled treatment studies of BDD exist. We compared a relatively new innovative treatment (CBT-BDD) against a strong, active control condition that is a prevalent alternative.

This trial also had some limitations. The sample was predominantly female and well educated, which may not be fully representative of the BDD population. Enhancement of supportive psychotherapy in this study likely bolstered outcomes such that supportive psychotherapy may have been better than that typically provided in community practice. Differences in therapists’ training and experience were confounded with site effects and could have contributed to the observed variability in the effectiveness of supportive psychotherapy; the lack of random assignment to therapists and relatively small caseloads for some therapists precluded our examination of such effects. We also cannot rule out other site effects, such as the moderating properties of demographic differences, comorbidities, or treatment credibility, because the study was not powered to detect such differences. Attrition from CBT (27.9%) was higher than with briefer CBT-BDD (0%-19%)9,10,11; however, we could not detect that attrition differed between treatments and sites at this sample size. In addition, patient satisfaction was not assessed until week 12; thus, perhaps patients who terminated earlier were less satisfied.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that CBT-BDD appeared to be associated with more consistent improvement in BDD symptom severity and quality of life, whereas supportive psychotherapy response varied by site. Additional studies of BDD treatment are needed, especially large studies that examine the transportability of these treatments to real-world settings, such as community mental health centers. Future studies should also examine patient- and therapist-level predictors and moderators of treatment response and identify mechanisms of therapeutic change.

Trial Protocol

Methods and Results

eMethods. Recruitment, Demographics, Description of the Treatments, Training and Fidelity of Therapists, Training and Fidelity of Independent Evaluators, Randomization Procedures, Blinding Procedures, Adverse Events Monitoring, Survival Analysis of Drop-out, Assessment of Missingness Methods

eResults. Treatment Adherence and Competence, Blinding Effectiveness, Primary and Secondary Outcomes During Follow-up: Table of Model Estimates, Survival Analysis of Dropout, Assessment of Missingness Results

eTable 1. Tests of Intercept Differences (Treatment, Site, Treatment*Site), Overall Slope Effects (Time), and Slope Differences (Time*Treatment, Time*Site, Time*Treatment*Site) in Random Intercept Random Coefficient Models of Primary and Secondary Treatment Outcomes During Follow-up (Weeks 24-50)

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Evaluated as Risk Factors for Early Drop-out from Treatment

eFigure. Survival Curves of Time to Drop-out from Therapy During the Treatment Period

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Sisorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schieber K, Kollei I, de Zwaan M, Martin A. Classification of body dysmorphic disorder - what is the advantage of the new DSM-5 criteria? J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(3):223-227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, et al. Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(1):171-175. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koran LM, Abujaoude E, Large MD, Serpe RT. The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in the United States adult population. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(4):316-322. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900016436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rief W, Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S, Borkenhagen A, Brähler E. The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychol Med. 2006;36(6):877-885. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips KA, Quinn G, Stout RL. Functional impairment in body dysmorphic disorder: a prospective, follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(9):701-707. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips KA, Menard W. Suicidality in body dysmorphic disorder: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1280-1282. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen JC, Reiter J, Orosan P. Cognitive-behavioral body image therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(2):263-269. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veale D, Gournay K, Dryden W, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder: a cognitive behavioural model and pilot randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(9):717-729. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veale D, Anson M, Miles S, Pieta M, Costa A, Ellison N. Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy versus anxiety management for body dysmorphic disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(6):341-353. doi: 10.1159/000360740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabiei M, Mulkens S, Kalantari M, Molavi H, Bahrami F. Metacognitive therapy for body dysmorphic disorder patients in Iran: acceptability and proof of concept. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012;43(2):724-729. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Didie E, et al. Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2014;45(3):314-327. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enander J, Andersson E, Mataix-Cols D, et al. Therapist guided internet based cognitive behavioural therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: single blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2016;352:i241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips KA, Menard W, Quinn E, Didie ER, Stout RL. A 4-year prospective observational follow-up study of course and predictors of course in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):1109-1117. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR, DeCaria C, Goodman WK. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):17-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips KA, Albertini RS, Rasmussen SA. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in body dysmorphic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(4):381-388. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Fama JM, Greenberg JL, Steketee G. Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Ther. 2011;42(4):624-633. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deckersbach T, Savage CR, Phillips KA, et al. Characteristics of memory dysfunction in body dysmorphic disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6(6):673-681. doi: 10.1017/S1355617700666055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feusner JD, Bystritsky A, Hellemann G, Bookheimer S. Impaired identity recognition of faces with emotional expressions in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179(3):318-323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feusner JD, Townsend J, Bystritsky A, Bookheimer S. Visual information processing of faces in body dysmorphic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1417-1425. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinsker H. A Primer of Supportive Psychotherapy. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H, eds. Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(1):102-108. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition (BDI-II). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rush AJJ, First MB, Blacker D, eds. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321-326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257-260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73-86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233-237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Twisk J, Bosman L, Hoekstra T, Rijnhart J, Welten M, Heymans M. Different ways to estimate treatment effects in randomised controlled trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2018;10:80-85. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(1):43-53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook RJ, Farewell VT. Multiplicity considerations in the design and analysis of clinical trials. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 1996;159(1):93-110. doi: 10.2307/2983471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison A, Fernández de la Cruz L, Enander J, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;48:43-51. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cottraux J, Note I, Albuisson E, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive therapy in social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(3):137-146. doi: 10.1159/000012382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of cognitive behavior therapy with Rogerian supportive therapy in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: a 2-year follow-up. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):101-110. doi: 10.1159/000112887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T, Basten C. Treatment of acute stress disorder: a comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(5):862-866. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant RA, Sackville T, Dang ST, Moulds M, Guthrie R. Treating acute stress disorder: an evaluation of cognitive behavior therapy and supportive counseling techniques. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1780-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craske MG, Maidenberg E, Bystritsky A. Brief cognitive-behavioral versus nondirective therapy for panic disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1995;26(2):113-120. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(95)00003-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeRubeis RJ, Brotman MA, Gibbons CJ. A conceptual and methodological analysis of the nonspecifics argument. Clin Psychol. 2005;12(2):174-183. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? an update. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):270-277. doi: 10.1002/wps.20238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milrod B, Chambless DL, Gallop R, et al. Psychotherapies for panic disorder: a tale of two sites. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(7):927-935. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deacon BJ, Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, et al. Assessing therapist reservations about exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: the Therapist Beliefs about Exposure Scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(8):772-780. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Methods and Results

eMethods. Recruitment, Demographics, Description of the Treatments, Training and Fidelity of Therapists, Training and Fidelity of Independent Evaluators, Randomization Procedures, Blinding Procedures, Adverse Events Monitoring, Survival Analysis of Drop-out, Assessment of Missingness Methods

eResults. Treatment Adherence and Competence, Blinding Effectiveness, Primary and Secondary Outcomes During Follow-up: Table of Model Estimates, Survival Analysis of Dropout, Assessment of Missingness Results

eTable 1. Tests of Intercept Differences (Treatment, Site, Treatment*Site), Overall Slope Effects (Time), and Slope Differences (Time*Treatment, Time*Site, Time*Treatment*Site) in Random Intercept Random Coefficient Models of Primary and Secondary Treatment Outcomes During Follow-up (Weeks 24-50)

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Evaluated as Risk Factors for Early Drop-out from Treatment

eFigure. Survival Curves of Time to Drop-out from Therapy During the Treatment Period

Data Sharing Statement