Abstract

This study evaluates the inclusion of studies identified by the FDA as having falsified data in the results of meta-analyses.

Clinical trials under the purview of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been shown to report falsified data.1 The FDA warns researchers when falsified data are discovered, but these data have made it into the medical literature.1,2 The desire to include all available data in a meta-analysis to obtain the “best estimate” of effect size may result in the inclusion of falsified data, which may compromise future research, policy decisions, and patient care.3 The present study evaluates the inclusion of studies with falsified data in meta-analyses.

Methods

As identified by Seife,2 the ARISTOTLE clinical trial, which studied the pharmaceutical agent apixaban, had the most publications containing falsified data. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review, per the Cochran Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (PROSPERO Identifier: CRD42017055627),4 to identify meta-analyses that contained at least 1 ARISTOTLE clinical trial publication with falsified data. The institutional review board of Florida International University determined that board approval was not required because the study involved no human participants.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the inclusion of the ARISTOTLE trial in meta-analyses by determining the odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Estimates were calculated using either a fixed- or random-effects model outlined in each meta-analysis publication using the Mantel-Hanszel method.

Results

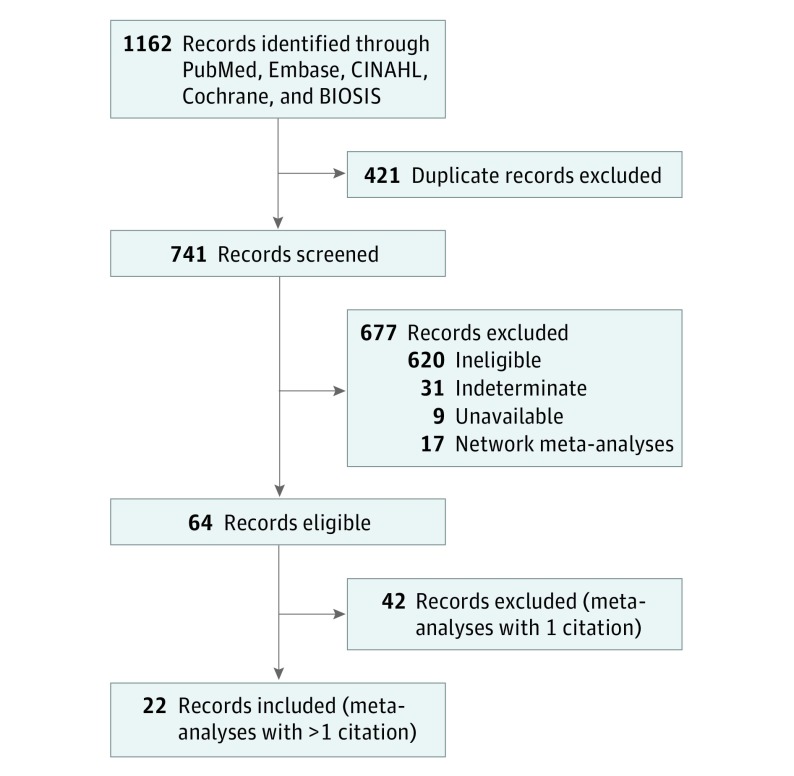

The ARISTOTLE clinical trial was found in 22 meta-analyses (Figure). All meta-analyses found were in English and published between 2012 and 2017. The median number of publications contributing to the analyses was 9 (range, 2-28), and the median meta-analysis publication InCite journal impact factor was 5.658 (range, 3.154-17.202). The median weight of the publication with falsified data toward each meta-analysis was 37.3% (range, 7%-100%).

Figure. Study Inclusion Flow Diagram.

In our reanalysis of the 22 meta-analyses, we found that 10 (46%) yielded results that would change the initial meta-analysis findings. Each affected meta-analysis had a median of 9.5 publications (range, 2-17), and the median meta-analysis publication InCite journal impact factor was 5.830 (range, 3.154-17.202). The median weight of publications with falsified data was 55.7% (range, 13.1%-99.6%).

From our reanalysis of the 22 meta-analyses, we found that 32 of 99 analyses (32%) yielded results that would change the conclusions of the initial analysis (Table). Of the 32 affected estimates, 31 (97%) no longer favored apixaban for the prevention of serious medical issues, and 1 (3%) favored the control.

Table. Sensitivity Analysis Estimate Changes.

| Meta-analysis Estimate Change | Meta-analyses, No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Full | All | |

| OR crossed 1.0 | 3 (15) | 2 (7) | 5 (5) |

| UCI crossed 1.0 | 8 (60) | 14 (43) | 22 (22) |

| OR and UCI crossed 1.0 | 2 (10) | 2 (7) | 4 (4) |

| LCI crossed 1.0 | 1 (5) | NA | 1 (1) |

| Total | 14 (44) | 18 (27) | 32 (32) |

Abbreviations: LCI, 95% lower confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; UCI, 95% upper confidence interval.

Of the 99 analyses, 32 (32%) were subgroup analyses, while 67 (68%) were full analyses (Table). Of the 32 subgroup analyses, 14 (44%) yielded results that would change the conclusions of the initial subgroup analyses. For the full analyses, 18 of 67 estimates (27%) had results that were affected.

Discussion

This study found that 46% of all meta-analysis publications had conclusions altered by publications with falsified data, and 32% of all the analyses had a considerable change in the outcome. Overall analyses were more robust than subgroup analyses against the effects of publications with falsified data. For ORs not statistically affected, the estimates generally moved toward the null when more than 1 publication remained.

This study was limited to only meta-analyses that contained ARISTOTLE publications identified by Seife to contain falsified data.2 Not all the data within the ARISTOTLE publications were falsified. However, because the researchers knowingly published falsified data, a form of research misconduct, we removed all ARISTOTLE data.5

Our sensitivity analysis results showed that conclusions may be altered in meta-analyses by the inclusion of publications with falsified data. This study should add impetus for robust sensitivity analyses and stronger protections against falsified data. Falsified data can affect not only the original publication, but also any subsequent meta-analyses and any resulting clinical or policy changes resulting from the findings of these studies.

References

- 1.Garmendia CA, Bhansali N, Madhivanan P. Research misconduct in FDA-regulated clinical trials: a cross-sectional analysis of warning letters and disqualification proceedings. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(5):592-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seife C. Research misconduct identified by the US Food and Drug Administration: out of sight, out of mind, out of the peer-reviewed literature. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):567-577. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):9-18. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00097-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Cochrane Collaboration Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0). https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 5.Office of Research Integrity, US Department of Health and Human Services Definition of Research Misconduct (April 25, 2011). https://ori.hhs.gov/definition-misconduct. Accessed September 5, 2018.