Key Points

Questions

To what extent do high-need Medicare beneficiaries switch to and from Medicare Advantage plans, and what influences these decisions?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of more than 13.9 million Medicare Advantage enrollees found that among high-need enrollees, 4.6% of Medicare-only and 14.8% of Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries switched to traditional Medicare compared with 3.3% and 4.6%, respectively, among non–high-need enrollees. Among dual-eligible enrollees who began in traditional Medicare plans, 15.0% switched into Medicare Advantage, and plan quality ratings were associated with disenrollment.

Meaning

Disenrollment from Medicare Advantage may indicate that plans do not meet the preferences of enrollees with significant chronic illness and may complicate performance measurement and risk adjustment for Medicare Advantage plans.

This cross-sectional study characterizes trends in switching to and from Medicare Advantage plans among high-need beneficiaries and evaluates the drivers of disenrollment decisions among US Medicare enrollees.

Abstract

Importance

How often enrollees with complex care needs leave the Medicare Advantage (MA) program and what might drive their decisions remain unknown.

Objective

To characterize trends in switching to and from MA among high-need beneficiaries and to evaluate the drivers of disenrollment decisions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study of MA and traditional Medicare (TM) enrollees from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2015, used a multinomial logit regression stratified by Medicare-Medicaid eligibility status. All 14 589 645 non–high-need MA enrollees and 1 302 470 high-need enrollees in the United States who survived until the end of 2014 were eligible for the analysis. Data were analyzed from November 1, 2017, through August 1, 2018.

Exposures

Enrollee dual eligibility and high-need status (based on complex chronic conditions, multiple morbidities, use of health care services, functional impairment, and frailty indicators), MA plan star rating, and cost sharing.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of enrollees who disenrolled into TM, remained in the same MA plan, or who switched plans within the MA program.

Results

A total of 13 901 816 enrollees were included in the analysis (56.2% women; mean [SD] age, 70.9 [9.9] years). Among the 1 302 470 high-need enrollees, an adjusted 4.6% (95% CI, 4.5%-4.6%) of Medicare-only and 14.8% (95% CI, 14.5%-15.0%) of Medicare-Medicaid members switched from MA to TM compared with 3.3% (95% CI, 3.3%-3.3%) and 4.6% (95% CI, 4.5%-4.7%), respectively, among non–high-need enrollees. Among enrollees in low-quality plans, 23.0% (95% CI, 22.3%-23.9%) of Medicare and 42.8% (95% CI, 40.5%-45.1%) of dual-eligible high-need enrollees left MA. Even in high-quality plans, high-need members disenrolled at higher rates than non–high-need members (4.9% [95% CI, 4.6%-5.2%] vs 1.8% [95% CI, 1.8%-1.9%] for Medicare-only enrollees and 11.3% vs 2.4% dual eligible enrollees). Enrollment in a 5.0-star rated plan was associated with a 30.1–percentage point reduction (95% CI, −31.7 to −28.4 percentage points) in the probability of disenrollment among high-need individuals. A $100 increase in monthly premiums was associated with a 33.9–percentage point increase (95% CI, −34.9 to −33.0 percentage points) in the likelihood of switching plans, and a small reduction in the likelihood of disenrolling (−2.7 percentage points; 95% CI, −3.2 to −2.2 percentage points). Among Medicare-Medicaid eligible participants, 14.1% (95% CI, 14.0%-14.2%) of high-need and 16.7% (95% CI, 16.6%-16.7%) of non–high-need enrollees switched from TM to MA.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this study suggest that substantially higher disenrollment from MA plans occurs among high-need and Medicare-Medicaid eligible enrollees. This study’s findings suggest that star ratings have the strongest association with disenrollment trends, whereas increases in monthly premiums are associated with greater likelihood of switching plans.

Introduction

To improve the performance of the Medicare program, we must understand how to care for high-need enrollees1 who may have multiple morbidities,2 impairment in activities of daily living,3 and general frailty4 that increase service demand. Care coordination can be an important strategy to address their complexities5,6,7; however, limited mechanisms are available to provide greater coordination in traditional Medicare (TM). Medicare Advantage (MA) was designed to fill that gap.8

More than one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are now enrolled in MA, an increase from 19% in 2007.9 Medicare Advantage differs from TM in that private insurance plans are paid by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on a capitated basis to cover the care of their enrollees. Because payments are fixed, this model incentivizes payers to reduce spending. Medicare Advantage plans may emphasize better primary care and care management services for high-need enrollees to prevent expensive acute services down the line.10,11 Two potential barriers to these benefits exist: capitated payments when not properly risk adjusted may incentivize “cream skimming” and “lemon dropping” (ie, attracting healthier individuals and dropping those with higher needs).12 Medicare Advantage plans may also restrict physician networks and require prior authorization for care. These policies may be challenging for high-need enrollees, potentially leading to poorer experiences. Understanding the experiences of high-need beneficiaries enrolled in MA is vital if the benefits of managed care are to work for this group.

Enrollees in MA often have lower hospitalization rates13 and fewer complications14; beneficial spillover effects have also been seen on the outcomes of TM enrollees.15,16 Studies have argued that changes initiated by the Medicare Modernization Act have reduced favorable selection bias into the program.17,18,19 However, a growing body of literature suggests that concerns remain regarding MA plans for high-need enrollees. Although some disenrollment may be driven by error in plan choice, MA switch to TM occurs at higher rates after significant health events20 and kidney failure.21 Evidence from the nursing home industry suggests that MA enrollees have access to lower-quality nursing homes22 and have high rates of disenrollment after admission.23 The Government Accountability Office has expressed concern that sicker patients disenroll in a biased manner.24 This possibility is of particular concern for patients with complex chronic conditions or multiple morbidities who stand to lose the most in disruptions to continuity of care.25,26,27,28 Disenrollment is often a sign of revealed preference,20 perhaps even more so if disenrollment rates are differential by patient type, which might suggest that the program does not address the preferences of these enrollees with high use of medical services. Although a recent report found that MA contracts may perform well for patients with chronic conditions,29 other work has found differences in plan-level MA outcomes may be driven primarily by the plan’s enrolled patient mix.30

First, we characterize disenrollment trends in the MA program among high-need and/or Medicare-Medicaid eligible (ie, dual-eligible) enrollees. Next, we evaluate plan characteristics associated with an enrollee’s choice to disenroll, remain in the MA program, or switch plans. Several studies have attempted to explain the drivers of MA plan choice31,32,33,34,35,36,37 in the era before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; we evaluate MA plan decision making after introduction of the law.

Methods

Data and Cohort

Our cohort consisted of all MA enrollees in a plan for at least 1 month from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2015, and who survived at least until the end of 2014. For additional analyses, we also include all TM enrollees who met the same criteria during the same time period to assess switching to MA. This study was determined to be exempt from review and informed consent by the institutional review board of Brown University.

We used the Master Beneficiary Summary Files to determine MA status. We used the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set to identify enrollees’ specific MA plans. We used publicly available star ratings from CMS to categorize plan quality. Medicare Advantage plan characteristics came from publicly reported CMS Landscape Files. Dual-eligible beneficiaries meet a state’s income and disease cutoffs for Medicaid coverage and federal Medicare eligibility requirements.38 We stratified all analysis by dual eligibility because dual-eligible participants are allowed to switch to TM at any time, have most of their cost sharing paid for by Medicaid, and may constitute a substantially different enrollee population. Data for identifying high-need status came from the Medicare Provider and Analysis Review file for hospitalizations,14 the Minimum Data Set for nursing home stays, the Outcome and Assessment Information Set for home health, and the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility–Patient Assessment Instrument for rehabilitation services.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was enrollment status at December 31, 2015, defined as (1) disenrolling from MA to TM in 2014 or 2015, (2) switching between MA plans in 2014 or 2015, or (3) staying in the same MA plan. We also evaluated the rates at which TM enrollees switched into the MA program during the study period. Medicare Advantage companies have been known to consolidate their contracts with one another,39 moving all enrollees from an originating contract into another and terminating the originating contract. To account for this, we used CMS Plan Crosswalk Files for 2015 that indicate when consolidations occur. If an enrollee was in a contract in 2014 that consolidated into a new contract in 2015 and they remained enrolled, they were classified as staying because they did not select a new plan.

Classification of High-Need Enrollees

Beneficiaries were first considered high need if they had 2 or more complex chronic conditions such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and depression or 6 or more chronic conditions from the list of 26 conditions provided in the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse and had used acute or post–acute health care services (details are provided in eTable 5 in the Supplement). Because the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse does not report full data for MA, we calculate these conditions from across data sources that do report MA diagnoses based on the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithms. If not identified through this first step, beneficiaries were also classified as high-need if they had complete dependency in activities of daily living as indicated in a post–acute care assessment or 2 or more diagnoses indicative of frailty in their inpatient claims, such as failure to thrive or malnutrition.40

Additional Explanatory Variables

We included enrollee characteristics for sex, race/ethnicity, and age. We included 2014 plan premiums and maximum out-of-pocket payments (MOOP) in our models because investigators have found these characteristics to be important drivers of plan choice.32,33,37 Beyond 2014 premiums, we included a flag of enrollment in the lowest premium and MOOP or highest star rating available in the country and net change in rating, premium, and MOOP between an enrollee’s 2014 plan and that plan in the following year to see how changes in plan characteristics influence decisions.41 We include MA star ratings that range from 2.0 to 5.0 stars in 0.5-star increments and are calculated annually at the contract level by CMS across 5 domains of quality and enrollee experience.42 We grouped contract star ratings into 2.0 to 2.5, 3.0 to 3.5, 4.0 to 4.5, and 5.0. We also included plan characteristics such as health maintenance organization or preferred provider organization and whether the plan offered drug coverage as additional controls and the overall plan hierarchical condition category risk score calculated by CMS to account for the underlying risk in each plan’s enrollee population.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from November 1, 2017, through August 1, 2018. We presented characteristics of high-need and non–high-need patients by contract star rating categories. We then plotted disenrollment from MA to TM through 2015 for high-need enrollees among all enrollees at the start of 2014, stratifying by star rating and dual-eligibility status and from TM to MA as a comparison.

To examine plan choice in 2015, we used a multinomial logit regression that allowed us to analyze our categorical outcome variable without natural ordering. We stratified by dual eligibility and high-need status to see how patterns differ between groups. We excluded enrollees who (1) moved between counties during 2014 or 2015 (n = 48 163); (2) those in special needs plans (SNPs), because their decision process and characteristics may be different (n = 787 298); and (3) those in contracts that were too new to rate or did not receive star ratings (n = 1 146 615). We also excluded those who sought hospice care (n = 456 070) during the study period.

We calculated adjusted mean disenrollment, stay, and switch rates by enrollee type and star rating, controlling for observable enrollee and plan characteristics. To more easily interpret how each plan characteristic is associated with enrollment decisions, we calculated the marginal effects of each plan characteristic on the probability of each outcome, holding all other variables constant. These marginal effects can be interpreted as the percentage point changes in the probability of an enrollee deciding to disenroll, stay, or switch, based on a change in plan characteristics.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. We fitted multinomial probit models to see if the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives held for our primary logit models (eTable 6 in the Supplement).43 Because characteristics of Special Needs Plans (SNPs) and non-SNPs may differ, we fitted additional models to include SNPs. All analyses were conducted in Stata software (version 15; StataCorp). Two-sided P < .05 indicated significance.

Results

In Table 1, we present demographic characteristics of the 13 901 816 enrollees in our sample (56.2% women and 44.7% men; mean [SD] age, 70.9 [9.9] years). White enrollees were more often enrolled in higher-rated contracts than nonwhite enrollees (77.1% white vs 8.3% black and 2.6% Hispanic non–high-need enrollees were in 5.0-star plans). Dual-eligible enrollees also tended to be enrolled in lower-rated contracts than non–dual-eligible enrollees (4.4% of non–high-need enrollees in 5.0-star plans were dual eligible compared with 17.3% of enrollees in 2.0- to 2.5-star plans). Enrollees in higher-rated plans tended to have higher mean monthly premiums (>$70 a month in 5.0-star contracts compared with $25 a month in 2.0- to 2.5-star contracts).

Table 1. Enrollee Characteristics by High-Need Status and Medicare Plan Star Rating.

| Characteristic | Plan Rating by High-Need Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non–High-Need Enrollees | High-Need Enrollees | |||||||

| 2.0-2.5 Stars (n = 186 865) | 3.0-3.5 Stars (n = 4 484 992) | 4.0-4.5 Stars (n = 6 950 775) | 5.0 Stars (n = 1 305 963) | 2.0-2.5 Stars (n = 14 908) | 3.0-3.5 Stars (n = 343 434) | 4.0-4.5 Stars (n = 536 880) | 5.0 Stars (n = 77 999) | |

| Female | 102 307 (54.7) | 2 516 506 (56.1) | 3 907 434 (56.2) | 730 200 (55.9) | 8634 (57.9) | 201 833 (58.8) | 309 955 (57.7) | 44 171 (56.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 141 410 (75.7) | 3 469 680 (77.4) | 5 939 092 (85.4) | 1 006 286 (77.1) | 10 868 (72.9) | 260 544 (75.9) | 458 644 (85.4) | 60 756 (77.9) |

| Black | 27 297 (14.6) | 588 885 (13.1) | 583 337 (8.4) | 107 960 (8.3) | 2866 (19.2) | 60 318 (17.6) | 55 108 (10.3) | 8505 (10.9) |

| Hispanic | 6576 (3.5) | 156 084 (3.5) | 134 007 (1.9) | 34 024 (2.6) | 665 (4.5) | 10 830 (3.2) | 10 290 (1.9) | 2171 (2.8) |

| Asian | 4640 (2.5) | 116 121 (2.6) | 96 890 (1.4) | 66 092 (5.1) | 187 (1.2) | 4988 (1.4) | 4324 (0.8) | 2938 (3.8) |

| Native American/Alaskan | 536 (0.3) | 9743 (0.2) | 12 541 (0.2) | 2254 (0.2) | 46 (0.3) | 956 (0.3) | 1242 (0.2) | 163 (0.2) |

| Other/unknown | 6406 (3.4) | 144 479 (3.2) | 184 908 (2.7) | 89 347 (6.8) | 276 (1.8) | 5798 (1.7) | 7272 (1.4) | 3466 (4.4) |

| Dual eligibility | 32 312 (17.3) | 672 250 (15.0) | 583 326 (8.4) | 56 858 (4.4) | 6182 (41.5) | 120 250 (35.0) | 113 327 (21.1) | 11 019 (14.1) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.2 (10.3) | 69.9 (10.0) | 71.4 (9.0) | 71.9 (8.4) | 70.8 (11.6) | 73.6 (11.5) | 75.5 (10.5) | 76.5 (9.9) |

| Plan characteristics | ||||||||

| Mean premium, $ | 25.4 | 16.6 | 38.1 | 72.6 | 26.9 | 19.1 | 48.2 | 84.9 |

| Mean MOOP, $ | 5661.5 | 4870.5 | 4490.3 | 3407.8 | 5557.3 | 4919.7 | 4476.9 | 3290.8 |

| Enrolled in highest star plan, % | 5.2 | 8.8 | 40.7 | 100.0 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 41.0 | 100.0 |

| Enrolled in lowest premium plan, % | 66.4 | 69.1 | 51.9 | 28.6 | 57.6 | 60.1 | 43.2 | 22.4 |

| Enrolled in lowest MOOP plan, % | 9.9 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 8.4 |

| Change in star rating 2014-2015 | −0.5 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Change in premium 2014-2015, $ | 13.27 | 11.44 | 5.18 | 6.21 | 8.53 | 10.84 | 5.4 | −7.42 |

| Change in MOOP 2014-2015, $ | −67.49 | 409.29 | 264.14 | 517.08 | −76.03 | 457.96 | 254.18 | 445.87 |

| No. of available plans, mean (SD) | 37.3 (27.7) | 39.4 (26.5) | 40.5 (25.6) | 44.2 (28.4) | 37.9 (28.0) | 40.6 (27.9) | 41.1 (26.3) | 45.1 (45.1) |

Abbreviation: MOOP, maximum out-of-pocket payment.

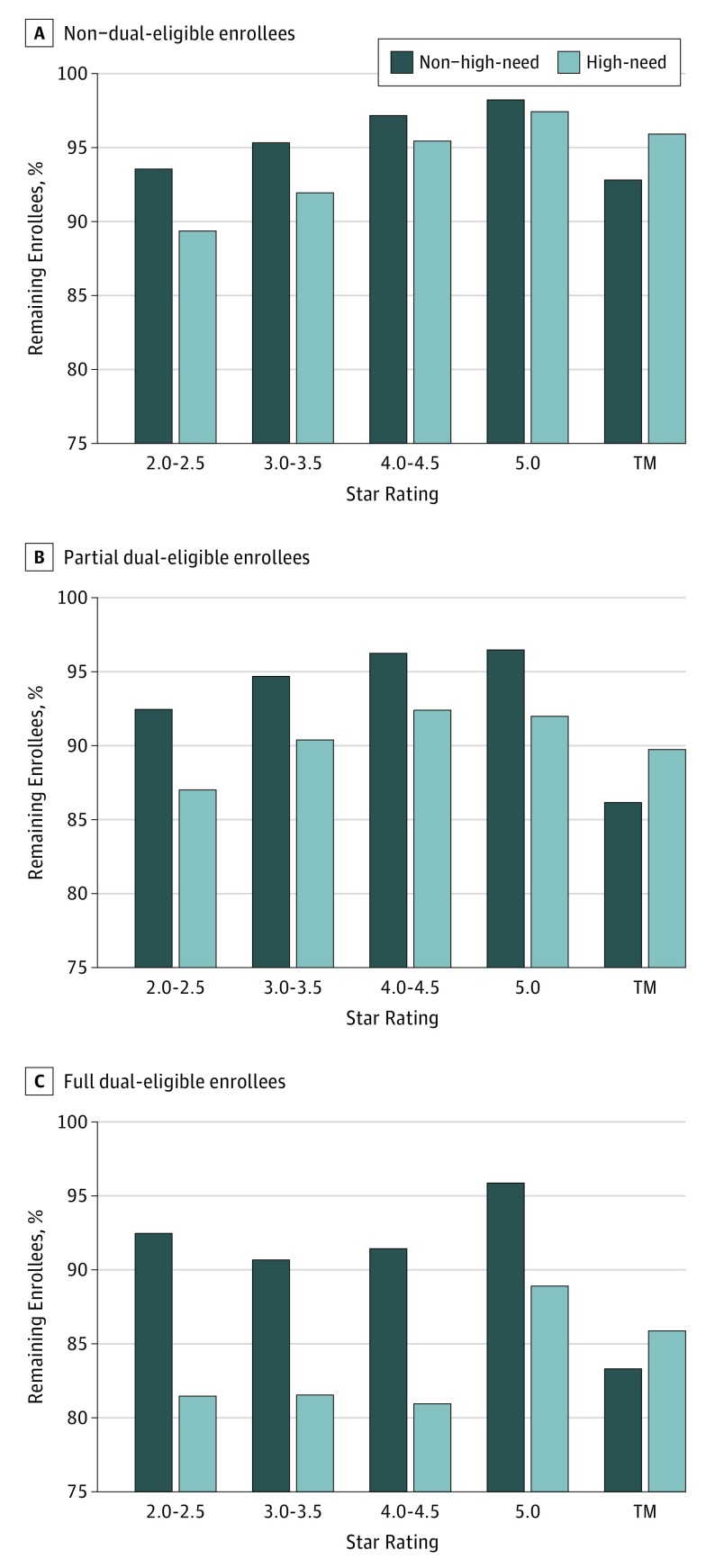

In the Figure, we plotted the percentage of enrollees who were still in an MA contract by the end of 2015 by star rating, conditional on survival. We also plotted the unadjusted percentage of beneficiaries who began 2014 in TM and remained in TM (and not MA) by the end of 2015. We stratified by high-need status and presented separate panels for beneficiaries who who did not have dual eligibility, only had partial dual eligibility, or had full dual eligibility. Across all groups, high-need enrollees had the highest rate of MA disenrollment by the end of 2015, with 2.6% (95% CI, 2.4%-2.7%) non– dual-eligible enrollees leaving the highest-rated plans and 10.6% (95% CI, 10.0%-11.2%) non–dual-eligible enrollees leaving the lowest rated plans. Disenrollment rates tended to be higher among those enrolled in lower-quality plans. Full dual-eligible enrollees left MA at the highest rates, with 11.1% (95% CI, 10.6%-11.6%) leaving the highest-rated plans and 18.5% (95% CI, 17.8%-19.3%) leaving the lowest-rated plans. However, dual-eligible beneficiaries also left TM to enter MA at the high rates, with more than 15% of non–high-need, fully dual-eligible TM enrollees switching to MA during the study period.

Figure. Percentage of Enrollees Who Remained in Traditional Medicare (TM) or Medicare Advantage (MA) at the End of 2015.

Enrollees are stratified by high-need or non–high-need and dual-eligibility status. High-need status was identified in 2014. Plan star ratings are from the 2014 enrolled plan. The percentage of enrollees who begin in MA or TM in 2014 and remain in MA or TM without moving between the 2 by the end of 2015 are plotted. The first 8 bars represent switching from MA to TM. The final 2 bars labeled TM represent switching from TM to MA. Partial dual-eligible enrollees receive some Medicaid benefits but do not have full eligibility in Medicare and Medicaid in 2014.

In Table 2, 23.0% (95% CI, 22.3%-23.9%) of non–dual-eligible, high-need enrollees in low-rated MA plans disenrolled to TM, and disenrollment was even higher at 42.8% (95% CI, 40.5%-45.1%) among comparable high-need dual-eligible enrollees. Generally, enrollees in lower-rated plans disenrolled at higher rates than enrollees in higher-rated plans. Even in 5.0-star plans, however, high-need enrollees were more likely to disenroll (4.9% [95% CI, 4.6%-5.2%] of non–dual-eligible high-need enrollees compared with 1.8% [95% CI, 1.8%-1.9%] of non–dual-eligible and 2.4% [95% CI, 2.1%-2.7%] of dual-eligible non–high-need enrollees). Full model coefficients can be found in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Enrollment Decisions by Plan Star Rating, High Need, and Dual-Eligibility Statusa.

| High-Need Dual-Eligibility Status | Plan Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2.0-2.5 Stars | 3.0-3.5 Stars | 4.0-4.5 Stars | 5.0 Stars | |

| Non–high need, non–dual eligible | |||||

| No. of enrollees | 11 583 849 | 154 553 | 3 812 742 | 6 367 449 | 1 249 105 |

| Disenrolled to TM, % (95% CI) | 3.3 (3.3-3.3) | 25.4 (25.1-25.8) | 4.6 (4.9-5.0) | 2.4 (2.4-2.4) | 1.8 (1.8-1.9) |

| Same plan, % (95% CI) | 77.4 (77.3-77.4) | 65.9 (65.5-66.2) | 61.8 (61.7-61.9) | 84.2 (84.2-84.3) | 85.8 (85.6-85.9) |

| Different plan, % (95% CI) | 19.3 (19.3-19.3) | 8.7 (8.6-8.9) | 33.2 (33.2-33.3) | 13.4 (13.4-13.4) | 12.4 (12.3-12.6) |

| High-need, non–dual-eligible | |||||

| No. of enrollees | 722 443 | 8726 | 223 184 | 423 553 | 66 980 |

| Disenrolled to TM, % (95% CI) | 4.6 (4.5-4.6) | 23.0 (22.3-23.9) | 5.4 (5.3-5.4) | 3.5 (3.5-3.6) | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) |

| Same plan, % (95% CI) | 74.9 (74.8-74.9) | 69.4 (68.7-70.3) | 63.1 (62.9-63.3) | 82.4 (82.3-82.6) | 81.9 (81.3-82.6) |

| Different plan, % (95% CI) | 20.5 (20.4-20.6) | 7.5 (7.1-7.8) | 31.5 (31.3-31.7) | 14.1 (14.0-14.2) | 13.2 (12.6-13.8) |

| Non–high-need, dual-eligible | |||||

| No. of enrollees | 1 344 746 | 32 312 | 672 250 | 583 326 | 56 858 |

| Disenrolled to TM, % (95% CI) | 4.6 (4.5-4.7) | 28.0 (26.6-29.4) | 7.3 (7.1-7.5) | 3.3 (3.2-3.4) | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) |

| Same plan, % (95% CI) | 77.9 (77.8-78.1) | 65.7 (64.2-67.2) | 61.7 (61.4-62.1) | 84.3 (84.1-84.5) | 85.6 (84.8-86.3) |

| Different plan, % (95% CI) | 17.4 (17.2-17.6) | 6.3 (5.7-6.8) | 31.0 (30.7-31.3) | 12.4 (12.2-12.5) | 12.0 (11.3-12.7) |

| High-need, dual-eligible | |||||

| No. of enrollees | 250 778 | 6182 | 120 250 | 113 327 | 11 019 |

| Disenrolled to TM, % (95% CI) | 14.8 (14.5-15.0) | 42.8 (40.5-45.1) | 16.0 (15.6-16.3) | 12.9 (12.7-13.2) | 11.3 (10.2-12.5) |

| Same plan, % (95% CI) | 67.2 (66.9-67.5) | 51.8 (49.5-54.1) | 55.6 (55.1-56.1) | 74.4 (74.0-74.8) | 75.1 (73.3-76.9) |

| Different plan, % (95% CI) | 18.0 (17.8-18.3) | 5.4 (4.6-6.1) | 28.5 (28.0-28.9) | 12.7 (12.4-12.9) | 13.6 (12.0-15.1) |

Abbreviation: TM, traditional Medicare.

All percentages are adjusted marginal means from multinomial logit models adjusted for plan and patient characteristics and fully interacted with high-need status. We fit 2 models, one with non–dual eligibility only, and the other with dual-eligibility only. An unadjusted version is available in the eTable 2 in the Supplement.

In Table 3, we present the marginal effects of plan characteristics on the likelihood that enrollees would disenroll from MA to TM, stay, or switch to a different MA plan. Non–dual-eligible high-need enrollees in 4.0- to 4.5- and 5.0-star rated plans had a lower probability of 29.1 (95% CI, −30.7 to −27.5) to 30.1 (95% CI, −31.7 to −28.4) percentage points of disenrolling and a higher probability of 24.9 (95% CI, 23.2-26.6) to 26.0 (95% CI, 24.1-27.9) percentage points of staying in the same plan than a non–dual-eligible high-need enrollee in a 2.0- or 2.5-star rated plan. Among high-need enrollees, a $100 premium increase in the following year was associated with a decrease in the probability of staying in the same plan by 33.9 percentage points (95% CI, −34.9 to −33.0 percentage points) and an increase in their probability of switching by 36.6 percentage points (95% CI, 35.7-37.4 percentage points). Conversely, a $1000 increase in MOOP was associated with a small 0.2–percentage point reduction (95% CI, −0.3 to −0.1 percentage points) in the likelihood of disenrolling and a 1.8–percentage point reduction (95% CI, −2.0 to −1.6 percentage points) in the likelihood of switching.

Table 3. Association of Plan Characteristics With Enrollee Enrollment Decisions.

| Effect by Dual Eligibility | Outcome of Medicare Enrollment, Percentage Point Probability of Making an Enrollment Decision in 2015a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non–High-Need Enrollees | High-Need Enrollees | |||||

| Disenroll | Stay | Switch | Disenroll | Stay | Switch | |

| Non–dual eligibility | ||||||

| $1000 Increase in following year MOOP | −0.4 (−0.4 to −0.4) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) | −0.9 (−0.9 to −0.9) | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) | −1.8 (−2.0 to −1.6) |

| $100 Increase in following year premium | −1.7 (−1.8 to −1.6) | −38.5 (−38.8 to −38.3) | 40.2 (40.0 to 40.4) | −2.7 (−3.2 to −2.2) | −33.9 (−34.9 to −33.0) | 36.6 (35.7 to 37.4) |

| 1-Star increase in following year rating | −0.6 (−0.6 to −0.6) | 2.7 (2.5 to 2.8) | −2.1 (−2.2 to −2.0) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.0) | 0.5 (0 to 0.9)b | −1.2 (−1.6 to −0.8) |

| 2014 3.0- to 3.5- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −20.7 (−21.1 to −20.4) | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.5) | 21.6 (21.4 to 21.8) | −25.0 (−26.5 to −23.4) | 0.5 (−1.2 to 2.2)b | 24.5 (23.7 to 25.3) |

| 2014 4.0- to 4.5- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −23.4 (−23.8 to −23.1) | 21.0 (20.6 to 21.3) | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.7) | −29.1 (−30.7 to −27.5) | 24.9 (23.2 to 26.6) | 4.1 (3.4 to 4.9) |

| 2014 5.0- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −23.9 (−24.2 to −23.6) | 21.3 (20.9 to 21.7) | 2.6 (2.4 to 2.9) | −30.1 (−31.7 to −28.4) | 26.0 (24.1 to 27.9) | 4.1 (2.9 to 5.2) |

| 2014 Enrollment in highest-rated plan | −0.6 (−0.7 to −0.6) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.2) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.4) | −0.6 (−1.0 to −0.2) |

| 2014 Enrollment in lowest MOOP plan | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 5.8 (5.6 to 5.9) | −6.0 (−6.1 to −5.8) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.0) | 5.1 (4.5 to 5.8) | −6.8 (−7.3 to −6.3) |

| 2014 Enrollment in lowest premium plan | −1.9 (−2.0 to −1.9) | 6.4 (6.3 to 6.5) | −4.5 (−4.6 to −4.3) | −2.0 (−2.3 to −1.8) | 5.4 (4.9 to 5.9) | −3.4 (−3.9 to −2.9) |

| Dual eligibility | ||||||

| $1000 Increase in following year MOOP | −0.5 (−0.6 to −0.4) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | −1.0 (−1.1 to −0.8) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8) | −1.4 (−1.7 to −1.0) |

| $100 Increase in following year premium | −0.8 (−1.1 to −0.5) | −38.8 (−39.5 to −38.1) | 39.6 (38.9 to 40.2) | −5.3 (−6.7 to −3.9) | −29.4 (−31.3 to −27.6) | 34.7 (33.2 to 36.2) |

| 1-Star increase in following year rating | 0 (−0.1 to 0.2)a | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) | −1.9 (−2.2 to −1.5) | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.6) | −2.4 (−3.3 to −1.5) | −1.5 (−2.3 to −0.8) |

| 2014 3.0- to 3.5- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −19.8 (−20.6 to −18.9) | −2.7 (−3.6 to −1.8) | 22.5 (22.1 to 22.9) | −32.0 (−34.5 to −29.5) | 9.0 (6.5 to 11.5) | 23.0 (22.0 to 24.1) |

| 2014 4.0- to 4.5- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −21.7 (−22.6 to −20.9) | 16.4 (15.4 to 17.3) | 5.4 (4.9 to 5.8) | −35.0 (−37.6 to −32.5) | 29.0 (26.5 to 31.5) | 6.0 (5.0 to 7.1) |

| 2014 5.0- vs 2.0- to 2.5-Star rated plan | −20.2 (−21.2 to −19.3) | 15.3 (14.2 to 16.5) | 4.9 (4.1 to 5.7) | −37.0 (−39.9 to −34.2) | 29.3 (26.1 to 32.5) | 7.8 (5.8 to 9.8) |

| 2014 Enrollment in highest-rated plan | −0.4 (−0.5 to −0.3) | 5.1 (4.8 to 5.4) | −4.7 (−5.0 to −4.5) | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.7) | 0.1 (−0.7 to 0.9)b | −2.1 (−2.8 to −1.4) |

| 2014 Enrollment in lowest maximum OOP plan | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 5.1 (4.6 to 5.5) | −6.1 (−6.5 to −5.7) | 0.6 (−0.4 to 1.5) | 7.6 (6.4 to 8.8)b | −8.2 (−9.1 to −7.3) |

| 2014 Enrollment in lowest premium plan | −3.1 (−3.2 to −2.9) | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.5)b | 2.9 (2.6 to 3.3) | −2.3 (−3.0 to −1.6) | 0.8 (−0.2 to 1.7)b | 1.5 (0.7 to 2.4) |

Abbreviation: MOOP, maximum out-of-pocket payment.

An enrollee’s enrollment in the best-rated plan available to them in 2014 was associated with a 0.5–percentage point reduction in their probability of disenrolling, associated with a 3.3–percentage point increased probability of remaining in the same contract and a 2.8–percentage point decrease in the probability of remaining in the Medicare Advantage program but changing plans. All marginal effects come from a multinomial logit model adjusted for plan and patient characteristics, and they fully interacted with high-need status. We fit 2 models, one with non–dual elibility only, and the other with dual-eligibility only.

Denotes not significant. All other margins are statistically significant at 2-sided P < .01.

In sensitivity analysis, the directionality and significance of all coefficients in a multinomial probit specification remain unchanged, and marginal effects were similar. When including SNP plans in the multinomial models, no substantial changes occurred in the pattern of results. In the eTable 4 in the Supplement, we also present a comparison of enrollment decisions for those who receive hospice services before they die. Disenrollment rates were substantially higher for those who received hospice benefits (57.3%) compared with those who did not (5.1%). We also present in eFigures 1 through 3 in the Supplement plots of the probability of a high-need or a non–high-need enrollee entering a plan with the highest ratings or lowest premiums available in their market in 2015 and found that high-need enrollees generally entered lower-premium and lower-quality plans.

Discussion

We find that high-need and dual-eligible enrollees have substantially higher disenrollment rates when compared with non–high-need enrollees. This finding aligns with that of the recent Government Accountability Office report on disenrollment25 and other recent examples from the literature20,21,44 that suggest that MA plans may not currently meet the preferences of high-need enrollees. We also found large movement of TM enrollees into MA during the study period, particularly among dual-eligible beneficiaries, indicating a high level of switching in this population.

Several factors may explain differential disenrollment during this study period. Although risk adjustment has mitigated some cream skimming,18 plans may still not have an incentive to retain their high-need enrollees, leading to adverse selection not on who enrolls in plans but on those who disenroll. The limitations (eg, narrow networks, prior authorizations, etc) enacted by MA plans to control costs may not align with the preferences of enrollees who have complex care needs. Lower disenrollment rates from high-rated plans may be indicative of these plans providing fewer restrictions in access to care or other benefits to such enrollees. Beneficiaries with better health and socioeconomic status may also be better equipped to make more informed plan choices when first enrolling in MA. High-need enrollees may select suboptimal contracts when they first enroll in the program, and, when faced with the limitations those contracts contain, may be prompted to switch more often than healthier enrollees. High-need enrollees may also be enrolled in lower-rated plans because their more serious health needs exert a downward pull on the overall contract rating.45

The high levels of disenrollment that we find present methodologic issues for investigators who seek to study the performance of MA in caring for high-need patients. Because patients with complex conditions disenroll at higher rates than healthier patients, the outcomes of complex patients in these plans cannot be readily assessed owing to the competing risk of disenrollment. Any effort to compare the outcomes of high-need patients between MA and TM without addressing these issues of selection are likely to be biased. The disenrollment of high-need enrollees may also substantially bias the payment and performance measurement of MA plans. If a plan receives higher risk-adjusted payments for carrying a larger burden of high-need enrollees, and these enrollees are disenrolling at higher rates, then these payments may not be well targeted.

The largest changes in enrollment status from TM to MA and from MA to TM occurred among enrollees with dual eligibility with Medicaid. This finding is likely explained in part by dual-eligible enrollees being able to switch plans at any point during the year. An interplay between a state Medicaid managed care program and an MA plan may encourage more switching. The high levels of movement in this population warrant additional research.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows for special enrollment periods for moving between TM and MA and between MA contracts. These special enrollment periods may occur if an enrollee gains or loses Medicaid coverage, if an enrollee is admitted to an SNP and switches to an institutional contract, or if an enrollee is diagnosed with a chronic condition that can fall under an SNP or a PACE (Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly) contract, all of which may help explain increased movement among high-need enrollees.46 The special enrollment periods may also occur to allow enrollees to switch into contracts rated 5.0 stars, switch away from consistently low-rated reported contracts, and to leave contracts sanctioned by CMS, which may explain shifts to higher- from lower-quality contracts. Under the MA quality improvement program, contracts rated 4.0 stars or greater are also provided a bonus payment that contracts may pass on to enrollees in additional benefits, leading to lower switch rates from higher-performing contracts.47

Limitations

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, full-encounter claims data are not available for MA enrollees, which limits our ability to detect all chronic conditions for MA enrollees.

Second, plan characteristics not included in our data may influence patient decision making. For example, we have little information on the physicians included in MA plan networks and cannot determine whether a physician entering or leaving a given contract’s network inspired an enrollee’s choice. We also exclude from our analysis contracts without star ratings from CMS. These contracts may attract more patients with serious care needs and may account for the decisions of some enrollees to leave their original contract.

Third, we are unable to determine the specific reason an enrollee left their MA contract. Although we hypothesize it may be owing to high-need enrollees facing limited networks in their MA plans that would not apply in TM, we cannot determine whether, for example, an out-of-network physician would actually provide better care of an enrollee than an in-network physician. A higher disenrollment rate for high-need enrollees does not necessarily imply a deficiency in care, but may indicate that an enrollee’s preferences are not being met.

Conclusions

We find that high-need enrollees, particularly those who are dual eligible, disenroll from MA at substantially higher rates than other enrollees. Thus, our findings suggest that caution is warranted when evaluating the performance of MA plans owing to the potential for selection bias stemming from differential disenrollment. As of now, disenrollment is only 1 of 35 to 45 measures included in the MA star ratings system. Weighting disenrollment more heavily may help incentivize plans to address these concerns further. Although MA may have the potential to provide greater care coordination to address complex patient needs, it is unclear whether high-need enrollees who stand to benefit the most from care coordination are in fact benefiting.

eTable 1. Fully Stratified Multinomial Logit Model Results

eTable 2. Unadjusted Enrollee Plan Decisions by Star Rating

eFigure 1. Probability of Entering Lowest Premium Available Plan by High Need and Dual Status

eFigure 2. Probability of Entering Lowest-Rated Available Plan, by High Need and Dual Status

eFigure 3. Percentage of High-Need and Non–High-Need Enrollees in Lower-, Average-, and High-Quality Plans

eTable 4. Comparing Disenrollment by Hospice Use

eTable 5. Chronic Conditions Used in High-Need Definition

eTable 6. Multinomial Logit Models including SNP Plans

eTable 7. Multinomial Probit Models

References

- 1.Joynt KE, Figueroa JF, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into potentially actionable cohorts. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1-2):62-67. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, et al. All-cause 1-, 5-, and 10-year mortality in elderly people according to activities of daily living stage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):485-492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03867.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figueroa JF, Joynt Maddox KE, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Jha AK. Concentration of potentially preventable spending among high-cost Medicare subpopulations: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(10):706-713. doi: 10.7326/M17-0767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson GF, Ballreich J, Bleich S, et al. Attributes common to programs that successfully treat high-need, high-cost individuals. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(11):e597-e600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galbraith AA, Meyers DJ, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Long-term impact of a postdischarge community health worker intervention on health care costs in a safety-net system. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(6):2061-2078. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal D, Anderson G, Burke S, Fulmer T, Jha AK, Long P Tailoring complex-care management, coordination, and integration for high need, high cost patients. National Academy of Medicine’s Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Tailoring-Complex-Care-Management-Coordination-and-Integration-for-High-Need-High-Cost-Patients.pdf. September 19, 2016. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 8.Blumenthal D, Abrams MK. Tailoring complex care management for high-need, high-cost patients. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1657-1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T Medicare Advantage 2017 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2017-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/. June 6, 2017. Accessed February 17, 2018.

- 10.Rosenzweig JL, Taitel MS, Norman GK, Moore TJ, Turenne W, Tang P. Diabetes disease management in Medicare Advantage reduces hospitalizations and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(7):e157-e162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen R, Lemieux J, Schoenborn J, Mulligan T. Medicare Advantage chronic special needs plan boosted primary care, reduced hospital use among diabetes patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):110-119. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mello MM, Stearns SC, Norton EC, Ricketts TC III. Understanding biased selection in Medicare HMOs. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):961-992. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afendulis CC, Chernew ME, Kessler DP. The effect of Medicare Advantage on hospital admissions and mortality. Am J Health Econ. 2017;3(2):254-279. doi: 10.1162/AJHE_a_00074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Rahman M, Trivedi AN, Resnik L, Gozalo P, Mor V. Comparing post-acute rehabilitation use, length of stay, and outcomes experienced by Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with hip fracture in the United States: a secondary analysis of administrative data. PLoS Med. 2018;15(6):e1002592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baicker K, Chernew ME, Robbins JA. The spillover effects of Medicare managed care: Medicare Advantage and hospital utilization. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1289-1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson G, Figueroa JF, Zhou X, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Recent growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment associated with decreased fee-for-service spending in certain US counties. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1707-1715. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2630-2640. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newhouse JP, Price M, McWilliams JM, Hsu J, McGuire TG. How much favorable selection is left in Medicare Advantage? Am J Health Econ. 2015;1(1):1-26. doi: 10.1162/AJHE_a_00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newhouse JP, McGuire TG. How successful is Medicare Advantage? Milbank Q. 2014;92(2):351-394. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675-1681. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):70-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):78-85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg EM, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Jung H-Y, Rahman M. Favorable risk selection in Medicare Advantage: trends in mortality and plan exits among nursing home beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(6):736-749. doi: 10.1177/1077558716662565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Government Accountability Office. Medicare Advantage: CMS should use data on disenrollment and beneficiary health status to strengthen oversight.GAO-17-393. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-393. April 28, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 25.Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Roth D, McNary SW, Goldman HH. Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program on chronic mental illness. Milbank Q. 1994;72(1):105-122. doi: 10.2307/3350340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitton CR, Adair CE, McDougall GM, Marcoux G. Continuity of care and health care costs among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(9):1070-1076. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng S-H, Chen C-C. Effects of continuity of care on medication duplication among the elderly. Med Care. 2014;52(2):149-156. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879-1885. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avalere Health. Medicare Advantage achieves cost-effective care and better outcomes for beneficiaries with chronic conditions relative to fee-for-service Medicare. http://go.avalere.com/acton/attachment/12909/f-0571/1. July 2018. Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 30.Ndumele CD, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, et al. Differences in hospitalizations between fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. Med Care. 2019;57(1):8-12. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Shrank WH. Association between Medicare Advantage plan star ratings and enrollment. JAMA. 2013;309(3):267-274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.173925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs PD, Buntin MB. Determinants of Medicare plan choices: are beneficiaries more influenced by premiums or benefits? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(7):498-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atherly A, Dowd BE, Feldman R. The effect of benefits, premiums, and health risk on health plan choice in the Medicare program. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):847-864. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00261.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han J, Urmie J. Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ plan switching decisions and information processing. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;75(6):721-745. doi: 10.1177/1077558717692883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Conway PH, Shrank WH. The roles of cost and quality information in Medicare Advantage plan enrollment decisions: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):234-241. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada SL, Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, O’Malley AJ, Heller A, Cleary PD. Market and beneficiary characteristics associated with enrollment in Medicare managed care plans and fee-for-service. Med Care. 2009;47(5):517-523. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195f86e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Advantage plan switching: exception or norm? issue brief. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-advantage-plan-switching-exception-or-norm-issue-brief/. September 20, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 38.Keohane LM, Stevenson DG, Freed S, Thapa S, Stewart L, Buntin MB. Trends in Medicare fee-for-service spending growth for dual-eligible beneficiaries, 2007-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1265-1273. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathews AW, Weaver C Insurers game Medicare system to boost federal bonus payments. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/insurers-game-medicare-system-to-boost-federal-bonus-payments-1520788658. Published March 11, 2018. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 40.Bélanger E, Silver B, Meyers DJ, et al. A retrospective study of administrative data to identify high-need Medicare beneficiaries at risk of dying and being hospitalized [published online January 2, 2019]. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4781-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Douven R, van der Heijden R, McGuire T, Schut FT. Premium levels and demand response in health insurance: relative thinking and zero-price effects. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23846. Revised May 2018. Accessed January 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Part C and D performance data. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. Published August 10, 2017. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- 43.de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145-172. doi: 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley GF. Impact of continued biased disenrollment from the Medicare Advantage Program to fee-for-service. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(4):mmrr.002.04.a08. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.002.04.a08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Report to Congress: social risk factors and performance under Medicare’s value-based purchasing programs. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/report-congress-social-risk-factors-and-performance-under-medicares-value-based-purchasing-programs. December 21, 2016. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 46.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Understanding Medicare Part C & Part D enrollment periods. https://www.medicare.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/11219-understanding-medicare-part-c-d.pdf. Revised December 2017. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 47.Duggan M, Starc A, Vabson B. Who benefits when the government pays more? pass-through in the Medicare Advantage program. J Public Econ. 2016;141:50-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Fully Stratified Multinomial Logit Model Results

eTable 2. Unadjusted Enrollee Plan Decisions by Star Rating

eFigure 1. Probability of Entering Lowest Premium Available Plan by High Need and Dual Status

eFigure 2. Probability of Entering Lowest-Rated Available Plan, by High Need and Dual Status

eFigure 3. Percentage of High-Need and Non–High-Need Enrollees in Lower-, Average-, and High-Quality Plans

eTable 4. Comparing Disenrollment by Hospice Use

eTable 5. Chronic Conditions Used in High-Need Definition

eTable 6. Multinomial Logit Models including SNP Plans

eTable 7. Multinomial Probit Models