Introduction

In 2015, the World Health Organization released their framework on “people-centred health services,” (1) emphasizing a focus on health care that consciously adopts individuals’, carers’, families’, and communities’ perspectives into trusted health systems. This article and others (2) sparked a movement among international policy makers, service providers, and professional disciplines, including the American Diabetes Association, to aspire to person-centered care rather than patient-centered care, particularly for people with long-term chronic illnesses. But what does person-centered care mean in the context of kidney diseases, and is it really a paradigm shift from the way care is currently provided?

Definition of Person-Centered Care

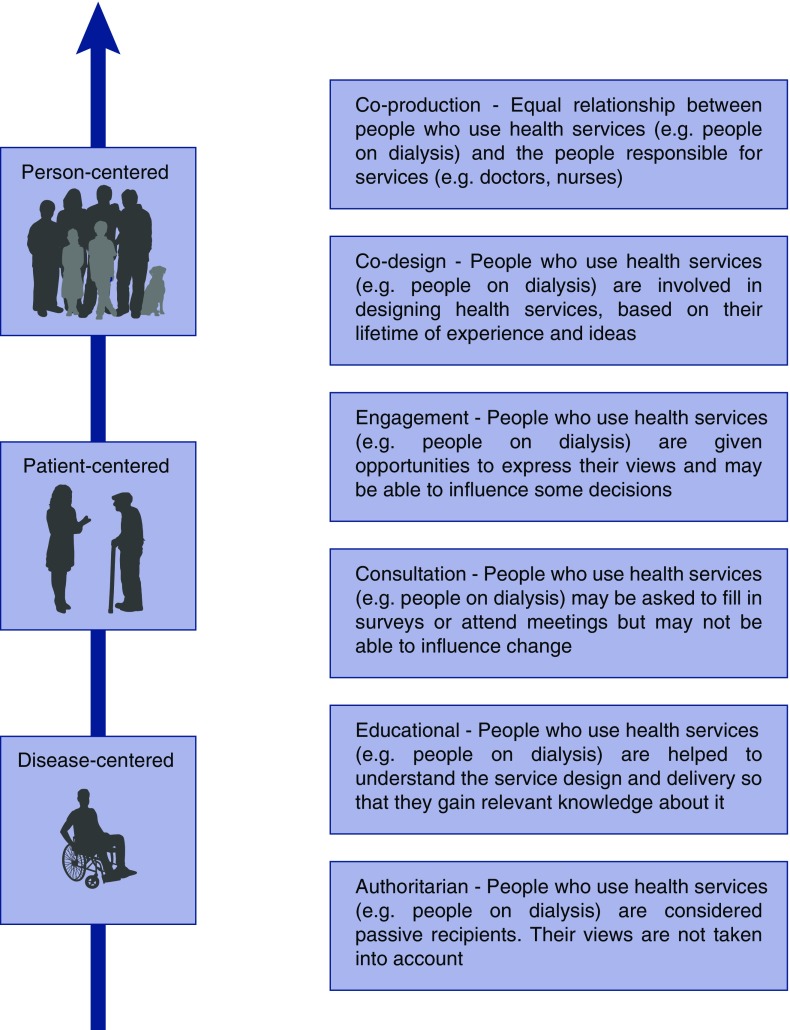

Person-centered care encompasses four distinct principles: (1) care is delivered with dignity, compassion, and respect; (2) care is well coordinated; (3) care is personalized taking into account clinical, social, emotional, and practical needs; and (4) care enables people to take an active role in their own care (2,3). In essence, person-centered care describes a focus on the individual, their family, and friends, rather than a focus on the disease; and promotes an equal relationship between people who use health services and the people responsible for services, rather than as a passive recipient (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evolution of person-centered health care in ESKD (7).

One of the main differences between person-centered and patient-centered care (although sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably) is a focus on the continuous nature of health care interactions between the individual and their health care team, and how an individual’s preferences, needs, and values for health care may evolve over their lifetime and influence that care. Person-centered care includes shared decision-making; however, it can go beyond this to include full coproduction health partnerships, where patients, carers, and their health care team work together as equal partners to influence health service design, service delivery, and service evaluation (4) (Figure 1). In person-centered care, people are not necessarily viewed through the narrow context of the health system, including being labeled as a patient. This acknowledges that people spend a relatively small amount of their time in a health care setting and the narrow view of people as patients from the perspective of the health system fails to acknowledge, and may even obscure, the person and what is most important to them. Patient-centered care, on the other hand, is primarily focused on the specific interactions within a health system, such as a doctor’s visit, a single hospitalization, or a procedure.

Examples of Person-Centered Care in CKD

The Implementing a Program of Shared Hemodialysis Care (SHAREHD) program in the United Kingdom is a quality assurance project across 12 hospitals that aims to increase long-term involvement in hospital-based dialysis care (5). The intervention is intended to improve the experience for those who choose to dialyze in hospital, and give people the confidence to select home dialysis, leading to a better quality of life. Outcomes of the program include the number of tasks people on dialysis perform independently, levels of activation, quality of life, kidney disease or treatment-related symptoms, and hospitalizations. SHAREHD is a collaborative approach to care, using shared goals rather than prescribed targets.

Another example of person-centered care in nephrology is the embedding of advance care planning into care for older people with CKD. Advance care planning helps to facilitate person-centered care by supporting people to consider and communicate decisions about their current and future care in the context of their own goals and values, as well as being aligned with a range of person-centered outcomes, such as dignity, respect, and good communication (3). The conceptualization of advance care planning has evolved over the past decade from the completion of advance directives to a process of care planning that occurs over time. A key feature of person-centered advance care planning (6) is that conversations are facilitated by trained professionals and take into account an individual’s preferences as they evolve over time, as their health and personal circumstances change. In contrast, the completion of an advance directive—a static, one-off document specifying end-of-life preferences (e.g., resuscitation, ventilation, withholding or continuing nutritional support)—is aligned with a patient-centered or disease-centered model of care, whereby end-of-life conversations become a checklist completed by health professionals. Furthermore, person-centered advance care planning is initiated at a time that is optimal for the individual, not in reaction to a health crisis or a change to the illness management plan. A comparative case-control study evaluating a nurse-led advance care planning program for adults on hemodialysis in Melbourne, Australia, found that those who undertook the program were significantly more likely to have their preferences known and adhered to by their treating doctor at their end of life (8). This program demonstrated that a coordinated approach to care facilitated by a trained dialysis nurse, working in collaboration with treating doctors, could uphold a critical, person-centered outcome by enabling preferences to be articulated, documented, and adhered to at the end of life.

A further example of person-centered care can be found in the redesign of the young adult kidney clinic in Salford, United Kingdom (9). After consultation with patients and families, this clinic now provides 16- to 30-year-olds with personalized care, counseling, career and welfare benefits information, all in the one unit. This is relevant to person-centered care because it considers the social circumstances and needs of the individual beyond the management of kidney disease.

Advantages of Person-Centered Kidney Care

There are many claims of benefit related to a person-centered care approach, including improved health care quality, outcomes, and safety; cost-effectiveness of care; and improved individual, family, and staff satisfaction (2). In a review of person-centered, integrated care in nephrology (10), 14 randomized trials were identified, with the majority focusing on education and self-care for people with CKD stages 3–4. Fewer hospitalizations and improved BP control were significant benefits when compared with standard care; however, the general quality of the trials was low.

Resources to Assist in Developing Person-Centered Kidney Care

Past studies suggest the availability of person-centered interventions, such as those highlighted above, are limited across kidney treatment services. This may be because there is a lack of evidence about how best to implement such person-centered interventions or the perception by health care professionals that the care they provide is already person-centered. Techniques such as experience-based codesign, and person- and family-centered care (2), as well as practical training in self-management support and shared decision-making, can help develop new understandings about what the health care team believe patients experience and what patients say they actually experience. A useful tool for assessing the level of person-centeredness in a kidney service is the Person-Centered Practice Inventory – Staff tool (11).

In summary, person-centered care is a new way of thinking about kidney service design and production for people with kidney disease, their families, and kidney healthcare professionals. It represents a shift from the historical way nephrology services were designed to operate because it places on equal footing an individual’s preferences, needs, and values as they evolve over time, as well as taking into account any other personal circumstances. The potential implications of a move to person-centered care from disease-centered or patient-centered care include a collaborative approach to care, using shared goals rather than prescribed targets; a greater understanding by the individual of their condition and their treatment, which leads to better decision-making and a more positive experience of care; and, with increased input from the people who use kidney services and the people responsible for them, a better codesign and coproduction of kidney services.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

R.L.M. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) fellowship (1150989).

The content of this article reflects the views and opinions of the authors, and may not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN). Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services, 2015. Available at: http://www.whoint/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en/. Accessed August 17, 2018

- 2.The Health Foundation: Person-Centred Care Made Simple, London, UK, The Health Foundation, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon J: Person-centred care. Chapter 4, in: Thomas, Lobo, and Detering (ed) Advance Care Planning in End of Life Care, 2017. Available at: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198802136.001.0001/oso-9780198802136-chapter-4. Accessed February 9, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victoria State Government: Doing it with Us Not for Us: Strategic Direction 2010-13. 50 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Victorian Government, Department of Health, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fotheringham J, Barnes T, Dunn L, Lee S, Ariss S, Young T, Walters SJ, Laboi P, Henwood A, Gair R, Wilkie M: Rationale and design for SHAREHD: A quality improvement collaborative to scale up shared haemodialysis care for patients on centre based haemodialysis. BMC Nephrol 18: 335, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gundersen Health System. Respecting Choices—Person Centered Care, 2017. Available at: URL http://www.gundersenhealth.org/respecting-choices/. Accessed February 9, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Co-production Advisory Group (NCAG). Ladder of co-production. Think Local Act Personal, National Health System, UK, 2019. Available at: https://www.thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk/Latest/Co-production-The-ladder-of-co-production/. Accessed February 9, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sellars M, Morton RL, Clayton JM, Tong A, Mawren D, Silvester W, Power D, Ma R, Detering KM: Case–control study of end-of-life treatment preferences and costs following advance care planning for adults with end stage kidney disease. Nephrology 24: 148–154, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer N: Exploring the journey towards person-centred care in CKD. Journal of Kidney Care. 1: 222–223, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentijn PP, Pereira FA, Ruospo M, Palmer SC, Hegbrant J, Sterner CW, Vrijhoef HJM, Ruwaard D, Strippoli GFM: Person-centered integrated care for chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 375–386, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B: The development and testing of the Person-Centred Practice Inventory - Staff (PCPI-S). Int J Qual Health Care 29: 541–547, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]