Abstract

Kidney palliative care is a growing discipline within nephrology. Kidney palliative care specifically addresses the stress and burden of advanced kidney disease through the provision of expert symptom management, caregiver support, and advance care planning with the goal of optimizing quality of life for patients and families. The integration of palliative care principles is necessary to address the multidimensional impact of advanced kidney disease on patients. In particular, patients with advanced kidney disease have a high symptom burden and experience greater intensity of care at the end of life compared with other chronic serious illnesses. Currently, access to kidney palliative care is lacking, whether delivered by trained kidney care professionals or by palliative care clinicians. These barriers include a gap in training and workforce, policies limiting access to hospice and outpatient palliative care services for patients with ESKD, resistance to integrating palliative care within the nephrology community, and the misconception that palliative care is synonymous with end-of-life care. As such, addressing kidney palliative care needs on a population level will require not only access to specialized kidney palliative care initiatives, but also equipping kidney care professionals with the skills to address basic kidney palliative care needs. This article will address the role of kidney palliative care for patients with advanced kidney disease, describe models of care including primary and specialty kidney palliative care, and outline strategies to improve kidney palliative care on a provider and system level.

Keywords: kidney palliative care, renal supportive care, person-centered care, quality of life, symptom management, palliative care, nephrology, outpatient care, ambulatory care

Why Kidney Palliative Care?

The disease continuum for patients with kidney disease is punctuated by psychological distress, high physical symptom needs, and increased medicalization that escalates at the end of life. These symptoms are prominent across the spectrum of CKD including late-stage CKD, dialysis, and comprehensive conservative care (active medical management without dialysis, abbreviated as CCC) (1,2). Symptom severity is comparable to that of advanced cancer, noted to be between 9 and 12 symptoms (1–3). These symptoms, especially psychological distress, may begin early in the disease course (4). Untreated anxiety and depression can lead to further setbacks including medication nonadherence, hospitalization, and death (5–10).

Patients with kidney disease face limited survival compared with the general population. Although mortality trends have improved somewhat over time, median survival for all-comers on maintenance dialysis remains low, at about 4–5 years (11). Despite this limited survival, dialysis care is often focused on longevity over quality of life, especially near the end of life. Patients on dialysis experience more hospitalizations, including intensive care stays, higher death risk in the hospital, and less use of hospice services as compared with their counterparts with advanced cancer or advanced heart failure (12). Among nursing home residents with serious illness in the last year of life, those on dialysis were less likely to prepare for future setbacks including fewer treatment-limiting directives or designation of a surrogate decision maker than those with other serious illnesses (13).

In practice, kidney palliative care (KPC) improves patient outcomes by proactively addressing the burdens that people living with advanced kidney disease face (2). There are common misconceptions of KPC that lead to missed opportunities to enhance person-centered care. For example, palliative care is often conflated with end-of-life care. Although it encompasses this important domain, palliative care is for any person with serious illness, at any age and any stage, including those who are pursuing life-prolonging treatments. Importantly, accepting palliative care does not compel patients to decline treatments such as dialysis or transplantation (14). In this Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology article, we describe a conceptual model for KPC and outline current KPC models including primary and specialty KPC. We examine system-level strategies for delivering KPC, and discuss future directions to improve KPC access.

Conceptual Model of Kidney Palliative Care

The delivery of high-quality KPC requires all kidney care professionals within the interdisciplinary team to possess basic palliative care skills, as well as improving access to specialty-level palliative care. These basic palliative care skills are also known as primary palliative care skills, and encompass basic symptom management, person-centered communication, and goals of care elicitation; complex situations may be addressed by specialty palliative care (see Table 1). Because the number of chronically seriously ill patients with KPC needs will not be met by specialty-level palliative care alone (15,16), a strategy to best integrate palliative care principles in nephrology is to improve access to both primary and specialty-level palliative care.

Table 1.

Primary and specialty Kidney Palliative Care skills

| Primary Kidney Palliative Care | Specialty Kidney Palliative Care |

|---|---|

| Manage basic symptoms | Address refractory symptoms |

| Diagnose and start depression and anxiety treatment | Manage complex depression, anxiety, grief, and existential distress |

| Basic serious illness communication | Complex serious illness communication |

| Address prognostic understanding | Address complex goals of care |

| Normalize and initiate advance care planning | Manage conflict resolution regarding goals of care |

| Address basic goals of care |

Adapted from reference (15).

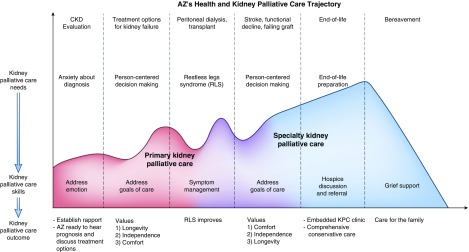

We describe KPC models that have been implemented in the United States, recognizing that a state-wide KPC model as practiced in parts of Canada and Australia is ideal. The United States KPC models are reflective of the local context, needs, and resources (see Table 2). We will describe primary and specialty KPC models following the story of patient AZ along his kidney disease trajectory (see Figure 1). This case demonstrates the role of primary palliative care as well as opportunities for specialty palliative care.

Table 2.

Models of kidney palliative care and representative kidney palliative care interventions

| Kidney Palliative Care Intervention | Model of Kidney Palliative Care | Staffing/Intervention | Additional Services Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baystate Medical Center (22) | Scaling primary KPC | Training for existing dialysis unit social workers and nephrologists | Facilitate advance care planning discussions with social workers and nephrologists for patients on dialysis with poorer prognosis |

| University of New Mexico (22) | 60 min lecture, review of training tape, didactic resources disseminated; social workers received additional 1-d intensive training. | ||

| NephroTalk (23) | Scaling primary KPC | Academic nephrologists trained to teach KPC skills | Curricular intervention that addresses nephrology fellowship training gap in teaching KPC skills |

| Zuckerberg SF General Hospital | Scaling primary KPC | Clinic staffed by academic nephrologist who completed palliative care courses, physician extenders, nurse, dietician, social worker | Fellow education (direct observation in clinic, KPC lectures, serious illness communication skills workshops) |

| Kidney CARES, NYU (31) | Embedded KPC | Nephrologist with palliative care training, partnership with Integrative Health Services, access to Nephrology Clinic staff | Embedded KPC provider addresses complex symptoms and patient-centered communication/decision making alongside routine kidney care, including comprehensive conservative care. |

| Renal Supportive Care Clinic, University of Pittsburgh | Embedded KPC | Nephrologist with palliative care training; access to Nephrology Clinic staff, Palliative Care home programs, and psychological resources | Embedded KPC provider addresses complex symptoms and patient-centered communication/decision making alongside routine kidney care, including comprehensive conservative care. |

| SPIRIT intervention, UNC (34) | Embedded KPC | Nurses undergo 3.5 d training in psychoeducational intervention | Advance care planning with dyads of patients on dialysis and their surrogates over two sessions in the dialysis facility and at home |

| Northwest Kidney Centers ESCO | Mobile/home-based KPC | Nephrologist with palliative care training, full-time social worker, and nurse | KPC team addresses complex patient-centered communication/decision making and symptom management in the dialysis facility and/or place of residence alongside routine kidney care. |

| Year-long palliative care training for social worker and nurse | |||

| Conservative Care Program, University of Calgary (44) | Embedded KPC and mobile/home-based KPC | Nephrologist with palliative care training, nurse dedicated to advance care planning, two half-time nurses for comprehensive conservative care, access to a social worker and dietician | Embedded clinic and home visit support for patients considering comprehensive conservative care |

| Kidney-specific symptom management support both before and during enrollment in hospice | |||

| Alberta Health Services (45) | State/provincial KPC (KPC integrated in governmental health systems) | Provincial guidelines outline a comprehensive conservative care pathway for primary care providers and kidney care professionals | Scale comprehensive conservative care provision within Canadian provincial health services via centralized tools and pathways |

| British Columbia Renal Agency (46) | |||

| Renal Supportive Care, Australia (2) | State/provincial KPC (KPC integrated in governmental health systems) | Embedded KPC model with palliative care specialist, senior KPC nurse, and social worker at each Renal Unit | Comprehensive conservative care delivered by embedded KPC team at each Renal Unit |

| Concurrent KPC services for patients on dialysis | |||

| KPC services scaled within Australian state health service |

KPC, kidney palliative care; SF, San Francisco; NYU, New York University; SPIRIT, Sharing Patient's Illness Representations to Increase Trust; UNC, University of North Carolina; CARES, Comprehensive Advanced Renal Disease and ESKD Support; ESCO, ESKD Seamless Care Organization.

Figure 1.

AZ’s health and kidney palliative care trajectory illustrate an example of primary KPC and specialty KPC delivery to address kidney palliative care needs in advanced kidney disease. Kidney palliative care needs are represented on the vertical axis; time is represented on the horizontal axis. The dashed lines divide major periods along AZ’s health trajectory, which are identified at the top of the figure. Kidney palliative care skills and outcomes corresponding to kidney palliative care needs are identified for each period in AZ’s health trajectory. KPC, kidney palliative care; RLS, restless legs syndrome.

Models of Primary Kidney Palliative Care

AZ is a 65-year-old man with longstanding type 2 diabetes complicated by diabetic retinopathy and progressive proteinuric kidney disease secondary to diabetic kidney disease for the past 12 years, referred by his primary care doctor for stage 4 CKD. His nephrologist Dr. BY recognizes that AZ seems nervous during the visit, and responds by addressing the patient’s concerns before discussing the details of his progressive diabetic kidney disease. AZ opens up that he “freaked out” when he heard that he had “stage 4 disease,” and is worried about how his kidney disease will change his life.

AZ’s azotemia trend suggests impending kidney failure. Over several visits, Dr. BY explores AZ’s values in more depth to best guide treatment decision-making. He tells Dr. BY that what is most important is maximizing time with his family. He is willing to accept the additional treatment burdens as long as he maintains his independence and ability to be with family. On the basis of his values of maximizing longevity and independence, Dr. BY recommends home dialysis while pursuing work-up for transplantation, and AZ ultimately chooses peritoneal dialysis.

After dialysis initiation, AZ’s uremic symptoms improve, and he enjoys time with his new grandchild. However, the restless legs syndrome (RLS) that appeared just before he started peritoneal dialysis worsens despite optimization of his iron indices. Dr. BY stops his metoclopramide, advises him to decrease caffeine intake, encourages exercise, and ultimately starts low-dose gabapentin, all of which result in significant improvement in his symptoms. At age 69, he receives a deceased donor kidney transplant, and he is ecstatic at his newfound free time. He does well for another 8 years, with only minor setbacks.

AZ’s case illustrates how primary palliative care can be incorporated within routine nephrology care. In this case Dr. BY uses primary palliative care skills to address AZ’s coping needs, goals of care, and distressing symptoms.

The first skill is person-centered communication, defined as active listening, responding to patient emotion, and gaining the patient perspective. By recognizing and responding to key emotional cues, Dr. BY improves AZ’s ability to hear disease-specific information. A study of older patients with cancer demonstrated that responding to emotional cues results in improved informational recall (17), a skill that is useful for our patient population to enhance the patient and family experience (18).

The second skill involves goals of care elicitation. This skill requires providing prognostic information and eliciting patient goals and values to inform treatment decisions, such as the appropriateness of dialysis, modality selection, transplantation, and CCC (19). For instance, one person may prioritize longevity and be willing to endure the burdens of a life-prolonging treatment such as dialysis. Another may prioritize the quality of life afforded by being free of treatment burdens and forego the likelihood of added survival associated with dialysis initiation (20,21). By understanding what is most important, Dr. BY recommends peritoneal dialysis to support AZ’s goals of independence and being with family.

The third skill is basic symptom management of physical and psychological symptoms. By actively listening to and exploring AZ’s concerns, Dr. BY diagnoses RLS. Using available online symptom guides, Dr. BY stopped offensive medications, performed routine evaluation, and started first-line management of RLS with gabapentin.

Organizations and institutions have invested in models for scaling primary KPC. This involves equipping members of the interdisciplinary team with primary palliative care skills and teaching these skills to fellows. At the nonprofit dialysis organization Dialysis Clinic, Inc., care coordinators are taught communication skills in how to discuss and complete advance care planning (ACP) with kidney patients. Baystate Medical Center and the University of New Mexico have implemented a multimodal shared decision-making intervention for dialysis social workers and nephrologists (22). One nephrology training program has invested in developing a primary KPC curriculum; the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) holds an annual 3-day communication training called NephroTalk to teach KPC communication skills to nephrology fellows at UPMC and across the country (23). This curriculum has been shared with nephrology and palliative care educators who are teaching NephroTalk at their institutions. However, teaching KPC skills remains a significant curriculum gap in United States nephrology training despite nephrology fellows identifying it as an important set of skills to acquire (24,25).

For kidney care professionals beyond fellowship seeking additional resources, there are educational opportunities available to gain skills in serious illness communication (see Table 3), ranging from formal courses to just-in-time conversation guides that have overcome common physician concerns regarding time and skill with ACP (26). The Renal Plus Clinic at the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital is an example of leveraging these resources; it is led by a nephrologist who completed two courses listed in Table 3 to hone basic palliative care skills and affords trainees an opportunity to formally practice KPC skills.

Table 3.

Tools and educational programs for serious illness communication

| Tools | Educational Programs |

|---|---|

| Best case/worst case scenario planning (38) | Center to Advance Palliative Care online modules (39) |

| Prepare for Your Care ACP tool (40) | Graduate Certificate in Palliative Care, |

| Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence, University of Washington (47) | |

| VitalTalk just-in-time smartphone application (41) | NephroTalk Communication Training |

| University of Pittsburgh (23) | |

| Serious Illness Conversation Guide, Ariadne Labs (26) | Palliative Care Education and Practice, |

| Center for Palliative Care, Harvard Medical School (49) | |

| Stanford Palliative Care Training Portal (48) | VitalTalk online and in-person serious illness communication workshops (42) |

| Communication Skills Pathfinder Portal (43) |

ACP, advance care planning.

Models of Specialty Kidney Palliative Care

Eight years after transplant, AZ experiences a number of major setbacks, including a stroke that has left him increasingly frail, requiring assistance with housework and preparing meals. He uses a walker and requires assistance with transfers. He has chronic allograft nephropathy, and Dr. BY recognizes the need to engage in anticipatory planning now that AZ’s kidney transplant trajectory portends graft failure. AZ understands that his health has worsened, and he expresses the importance of quality over quantity of life defined by prioritizing time at home with family. He worries that the treatment burdens of dialysis will distract him from what is most important to him. Dr. BY involves an embedded KPC clinic to deliver home-based CCC. The KPC team refers AZ to hospice after 6 months of further decline, and he receives home hospice for five more months before he dies peacefully at home, surrounded by family.

AZ’s case resolution underscores the inflection points that signal decline and the need to involve specialty palliative care services. Specialty palliative care is appropriate for complex symptom management, goals of care including conflict resolution, and need for home services including home-based palliative care and hospice. The two main specialty KPC models include (1) embedded KPC and (2) mobile/home-based KPC. These models differ in their approach to KPC delivery yet share a similar vision for creating practice change. Notably, most of the KPC programs in the United States have not published results yet, and it is possible they will change in the future.

Embedded Kidney Palliative Care

In the advanced cancer and heart failure settings, palliative care embedded within those clinics has been shown to improve access to palliative care (27); physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms; and timely hospice referrals (28,29). In addition, ACP documentation and hospice use were improved in the cancer setting (30). Within KPC, the Kidney Comprehensive Advanced Renal Disease and ESKD Support (CARES) Program (31) at New York University is modeled after the embedded kidney–palliative care clinic first started in Australia (2), modified after soliciting local institutional stakeholder feedback. Here, a dually trained specialist in nephrology and palliative care is part of the nephrology group practice and sees kidney-specific palliative care referrals one half day per week. The Kidney CARES program works collaboratively with nephrologists to address the palliative care needs of patients with serious kidney disease regardless of CKD stage or treatment choice (CCC or dialysis). Other embedded models such as the Renal Supportive Care Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh provide KPC alongside routine nephrology care, such as delivering CCC. Patients are referred by primary care physicians and nephrologists with care collaboratively shared or transitioned solely to the Renal Supportive Care Clinic. The clinic is staffed by two dual-trained palliative care nephrologists who utilize existing nephrology nonphysician staff to perform primary palliative care such as obtaining symptom scores, scanning and communicating ACP documents, and referring to home services such as hospice.

Mobile/Home-Based Kidney Palliative Care

Home-based palliative care has been associated with greater use of actionable advance directives and an increase in family involvement (32). This is particularly prescient given studies that uncovered goal discordant care at the end of life between patients on dialysis and their surrogates, and improvement in goal concordant care after engaging patients and their surrogates in ACP earlier (33,34).

The Mobile Renal Supportive Care program at Northwest Kidney Centers is a mobile/home-based KPC model developed to deliver palliative care to patients within the ESKD Seamless Care Organization (ESCO) program. ESCOs are essentially accountable care organizations for patients on dialysis and are intended to foster creative care models disincentivized by traditional Medicare. The Mobile Renal Supportive Care program addresses barriers associated with access to outpatient palliative care, the burden of clinic visits, and the need to flexibly engage family members outside of a clinic setting. The interdisciplinary team comprises a nephrologist trained in palliative care, a social worker, and a nurse. Team members engage patients and family members in the dialysis unit and in their residences, address KPC needs, and help coordinate care with the patients’ primary nephrologists and dialysis interdisciplinary team.

Creating Practice Change

Where does that leave the individual nephrologist who is interested in practice change? These models highlight key steps to creating KPC change in nephrology. The first step involves creating a diverse stakeholder group to define the KPC mission informed by local needs and resources. Ideally these experts should include senior leadership, administrators, nephrologists, palliative care specialists, patients, and caregivers. Each of the models described requires the support and input of a diverse stakeholder group.

The second step involves building a team. This team is led by a KPC champion, that is the person who will translate the KPC vision into action. Suppose, after stakeholder engagement, there is readiness for improving symptom management and a desire to address patient values for their care further upstream. Who within the practice could lead a pilot project to enhance how the practice addresses KPC needs? Just as critical as identifying a KPC champion, creating KPC change often requires creating a team with specified roles.

Existing interdisciplinary roles are ideal to deliver KPC skills. For instance, nephrologists and advance practice providers (APP) are responsible for prognostic understanding and guidance around treatment options after values have been elicited. Nurses typically have the skillset for symptom management in conjunction with the nephrologist/APP, social workers and psychologists have training to address psychological and emotional needs, and spiritual care providers can address existential and spiritual needs. In addition, there are KPC skills that may be addressed by various kidney team members. For example, a dietician may participate extensively in goals of care discussions in one practice setting, and in another it may be a social worker. The engagement and involvement of a nephrologist or APP, however, is critical to the success of KPC (35).

Now that the right people have been selected, the third step will be to define the organizational vision for KPC. The initial implementation of this vision will depend on the needs and resources of a given organization. As an example, one could start by developing a CCC pathway. For other organizations, successful KPC innovation involves building external relationships with palliative care, social service, or hospice organizations. For example, a Dialysis Clinic, Inc. ESCO is partnering with a large hospice organization to pilot a concurrent hospice with dialysis program. These patients have a hospice diagnosis related to ESKD—a situation that typically requires withdrawal of dialysis to receive hospice services, because hospice organizations cannot afford to pay for dialysis. By offering concurrent dialysis and hospice for a given time frame, patients and families may experience longer length of stay on hospice with improved end-of-life outcomes (36). This is one example of leveraging local resources and expertise to adapt and optimize KPC delivery.

Finally, it is important to develop an evaluation plan to align further KPC growth and innovation with organizational priorities. These outcomes may include improved patient perception of provider communication, earlier discussions of what patients would prioritize if they were to become sicker, improved symptom control, and financial metrics specific to the organization.

Future Steps

The United States does not yet have a state or national model of KPC delivery, although other countries such as Australia and Canada have implemented state (New South Wales Renal Supportive Care model) and provincial (Alberta Health Services Conservative Kidney Management Project, British Columbia Renal Agency Conservative Care Pathway) models of primary and secondary KPC services. The New South Wales model is an example of an embedded model that includes an interdisciplinary team that was initially started at one hospital, St. George Hospital in Sydney. The program gained national recognition after demonstrating stability or improvement in symptom burden and quality of life (2). In partnership with the New South Wales Ministry of Health, this program has been scaled throughout the state and in 2 years provided KPC to >2300 patients in a state of about 8 million people. This model highlights small steps nephrology clinic practices can take that lead to large-scale change.

In the United States, alternative payment models and payer-provider partnerships may provide additional opportunities to pilot KPC interventions. However, more must be—and can be—done to better align financial incentives with high-quality patient-centered care (37). It is clear from models outside the United States that active participation from governmental organizations is necessary to accelerate innovation. Two examples include reform to the ESKD payment model and hospice access. A pathway to a more comprehensive ESKD payment model might include CKD stage 5 not yet on dialysis and kidney transplantation in addition to patients with ESKD on dialysis. Hospice reimbursement could be updated to allow concurrent hospice and dialysis for patients with ESKD for a defined time period.

Conclusions

In summary, improved KPC access will require the entire kidney community, with a strategy to improve primary KPC skills of all kidney care professionals and access to specialty KPC programs. The broad lesson learned from implementation of these programs is to identify organizational priorities that align with building KPC capacity. Governmental support has been shown to accelerate KPC integration on a population level. Regardless of whether the practice change implemented by each kidney care professional is small or large in scale, building our national KPC capacity is critical to delivering person-centered care in the era of personalized medicine.

Disclosures

D.Y.L. is the Palliative Care Medical Advisor for Northwest Kidney Centers and J.O.S. is the Palliative Care Medical Advisor for Dialysis Clinic, Inc.

Acknowledgments

D.Y.L, J.S.S., and V.G. acknowledge support from the Cambia Health Foundation.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD: Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1057–1064, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP: CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 260–268, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Castillo G, Ikeler K, Orazi J, Abdel-Rahman E, Pai AB, Rivara MB, St Peter WL, Weisbord SD, Wilkie C, Mehrotra R: Symptom prioritization among adults receiving in-center hemodialysis: A mixed methods study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 735–745, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balogun RA, Abdel-Rahman EM, Balogun SA, Lott EH, Lu JL, Malakauskas SM, Ma JZ, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP: Association of depression and antidepressant use with mortality in a large cohort of patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1793–1800, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, Coplan JD, Weedon J, Wyka KE, Saggi SJ, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 196–206, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL: Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int 75: 1223–1229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA: Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int 74: 930–936, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troidle L, Watnick S, Wuerth DB, Gorban-Brennan N, Kliger AS, Finkelstein FO: Depression and its association with peritonitis in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 350–354, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Combe C, Piera L, Held P, Gillespie B, Port FK; Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int 62: 199–207, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal Asher D, Ver Halen N, Cukor D: Depression and nonadherence predict mortality in hemodialysis treated end-stage renal disease patients. Hemodial Int 16: 387–393, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Renal Data System: 2016 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurella Tamura M, Montez-Rath ME, Hall YN, Katz R, O’Hare AM: Advance directives and end-of-life care among nursing home residents receiving maintenance dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 435–442, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wentlandt K, Weiss A, O’Connor E, Kaya E: Palliative and end of life care in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 17: 3008–3019, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 368: 1173–1175, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.America’s Care of Serious Illness: 2015 state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation’s hospitals, New York, Center to Advance Palliative Care and National Palliative Care Research Center, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen J, van Weert JC, de Groot J, van Dulmen S, Heeren TJ, Bensing JM: Emotional and informational patient cues: The impact of nurses’ responses on recall. Patient Educ Couns 79: 218–224, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Hare AM: Patient-centered care in renal medicine: Five strategies to meet the challenge. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 732–736, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schell JO, Cohen RA: A communication framework for dialysis decision-making for frail elderly patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2014–2021, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urquhart-Secord R, Craig JC, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, Manns B, Howell M, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG, Harris DC, Thompson S, Schick-Makaroff K, Wheeler DC, van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Johnson DW, Howard K, Evangelidis N, Tong A: Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: An international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 444–454, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, Rose J, Masterson R, Johnson DW, Howard K: Dialysis modality preference of patients with CKD and family caregivers: A discrete-choice study. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 102–111, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eneanya ND, Goff SL, Martinez T, Gutierrez N, Klingensmith J, Griffith JL, Garvey C, Kitsen J, Germain MJ, Marr L, Berzoff J, Unruh M, Cohen LM: Shared decision-making in end-stage renal disease: A protocol for a multi-center study of a communication intervention to improve end-of-life care for dialysis patients. BMC Palliat Care 14: 30, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schell JO, Cohen RA, Green JA, Rubio D, Childers JW, Claxton R, Jeong K, Arnold RM: NephroTalk: Evaluation of a palliative care communication curriculum for nephrology fellows. J Pain Symptom Manage 56: 767–773.e2, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: A cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 233–239, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, Sullivan AM, Cohen LM, Block SD, Arnold RM: The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: National survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 813–820, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, Smith G, Paladino J, Lipsitz S, Gawande AA, Block SD: Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: A randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open 5: e009032, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeSanto-Madeya S, McDermott D, Zerillo JA, Weinstein N, Buss MK: Developing a model for embedded palliative care in a cancer clinic. BMJ Support Palliat Care 7: 247–250, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, Adams PA, Speck A, Johnson KS, Krishnamoorthy A, Yang H, Anstrom KJ, Dodson GC, Taylor DH Jr., Kirchner JL, Mark DB, O’Connor CM, Tulsky JA: Palliative care in heart failure: The PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 70: 331–341, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ: Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 733–742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walling AM, D’Ambruoso SF, Malin JL, Hurvitz S, Zisser A, Coscarelli A, Clarke R, Hackbarth A, Pietras C, Watts F, Ferrell B, Skootsky S, Wenger NS: Effect and efficiency of an embedded palliative care nurse practitioner in an oncology clinic. J Oncol Pract 13: e792–e799, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherer JS, Wright R, Blaum CS, Wall SP: Building an outpatient kidney palliative care clinical program. J Pain Symptom Manage 55: 108–116.e2, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerr CW, Tangeman JC, Rudra CB, Grant PC, Luczkiewicz DL, Mylotte KM, Riemer WD, Marien MJ, Serehali AM: Clinical impact of a home-based palliative care program: A hospice-private payer partnership. J Pain Symptom Manage 48: 883–92.e1, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song MK, Ward SE, Lin FC: End-of-life decision-making confidence in surrogates of African-American dialysis patients is overly optimistic. J Palliat Med 15: 412–417, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, Hamilton JB, Bridgman JC: Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 66(5): 813–822, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellars M, Tong A, Luckett T, Morton RL, Pollock CA, Spencer L, Silvester W, Clayton JM: Clinicians’ perspectives on advance care planning for patients with CKD in Australia: An interview study. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 315–323, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachterman MW, Hailpern SM, Keating NL, Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM: Association between hospice length of stay, health care utilization, and Medicare costs at the end of life among patients who received maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 792–799, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassel JB, Kerr KM, Kalman NS, Smith TJ: The business case for palliative care: Translating research into program development in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 50: 741–749, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor LJ, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, Tucholka JL, Brasel KJ, Johnson SK, Zelenski A, Rathouz PJ, Zhao Q, Kwekkeboom KL, Campbell TC, Schwarze ML: A framework to improve surgeon communication in high-stakes surgical decisions: Best case/worst case. JAMA Surg 152: 531–538, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Center to Advance Palliative Care: CAPC Curriculum Continuing Education Courses, 2018. Available at: https://www.capc.org/providers/courses/. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 40. The PREPARE Team: PREPARE for your care, 2018. Available at: https://prepareforyourcare.org/welcome. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 41. VitalTalk: VitalTalk Tips App, Version 2.0.0, 2018. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/vitaltalk-apps/. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 42. VitalTalk: VitalTalk Courses, 2018. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/courses/. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 43. Ariadne Labs, Center to Advance Palliative Care, VitalTalk: Communication Skills Pathfinder, 2019. Available at: https://communication-skills-pathfinder.org/. Accessed December 9, 2018.

- 44.Kamar FB, Tam-Tham H, Thomas C: A description of advanced chronic kidney disease patients in a major urban center receiving conservative care. Can J Kidney Health Dis 4: 2054358117718538, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alberta Health Services, Conservative Kidney Management Team: Conservative Kidney Management Pathway, 2016. Available at: http://ckmcare.com/. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 46. British Columbia Provincial Renal Agency: Conservative Care Pathway, 2017. Available at: http://www.bcrenalagency.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/BCPRA%20Conservative%20Care%20Pathway%20Guideline.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- 47. Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence: Graduate Certificate in Palliative Care, 2018. Available at: http://uwpctc.org/. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 48. Stanford Palliative Care: Stanford Palliative Care Training Portal, 2018. Available at: https://palliative.stanford.edu/. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 49. Harvard Medical School Center for Palliative Care: Palliative Care Education and Practice, 2018. Available at https://pallcare.hms.harvard.edu/courses/pcep. Accessed August 2, 2018.