Abstract

In the past decade, there have been increasing efforts to better define and quantify the short- and long-term risks of living kidney donation. Recent studies have expanded upon the previous literature by focusing on outcomes that are important to potential and previous donors, applying unique databases and/or registries to follow large cohorts of donors for longer periods of time, and comparing outcomes with healthy nondonor controls to estimate attributable risks of donation. Leading outcomes important to living kidney donors include kidney health, surgical risks, and psychosocial effects of donation. Recent data support that living donors may experience a small increased risk of severe CKD and ESKD compared with healthy nondonors. For most donors, the 15-year risk of kidney failure is <1%, but for certain populations, such as young, black men, this risk may be higher. New risk prediction tools that combine the effects of demographic and health factors, and innovations in genetic risk markers are improving kidney risk stratification. Minor perioperative complications occur in 10%–20% of donor nephrectomy cases, but major complications occur in <3%, and the risk of perioperative death is <0.03%. Generally, living kidney donors have similar or improved psychosocial outcomes, such as quality of life, after donation compared with before donation and compared with nondonors. Although the donation process should be financially neutral, living kidney donors may experience out-of-pocket expenses and lost wages that may or may not be completely covered through regional or national reimbursement programs, and may face difficulties arranging subsequent life and health insurance. Living kidney donors should be fully informed of the perioperative and long-term risks before making their decision to donate. Follow-up care allows for preventative care measures to mitigate risk and ongoing surveillance and reporting of donor outcomes to inform prior and future living kidney donors.

Keywords: Living donation; outcomes; Patient-centered care; Living Donors; Health Expenditures; Aftercare; quality of life; Kidney Failure, Chronic; kidney; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Insurance; Health; Registries; Nephrectomy; Salaries and Fringe Benefits

Introduction

Since the inception of the successful practice of living donor kidney transplantation in 1954, >150,000 living persons in the United States have donated a kidney to help a family member, a friend, or even a stranger (1). Worldwide, >35,000 living donor kidney transplants are performed each year (2). Living donors derive no medical benefit from donation, nor do they expect to, but living donors do deserve transparent information on the short- and long-term outcomes of donation to support informed decision-making, follow-up, and care (3). The risks of living donation are accepted as sufficiently low to justify the practice, but notably, much of the available evidence has been limited by short observation periods, a high proportion of donors lost to follow-up, insufficient power to quantify rare events, and limited racial diversity (4–6). Furthermore, until recently, most studies compared donors with the unscreened general population. Recognition of these deficiencies, and the vital need to address them, prompted a growing body of research over the past decade that has helped advance understanding of donor risks (7). The study methodologies include construction of multicenter cohorts (8,9), integration of national donor registries with other data sources to acquire longer-term information for a broader spectrum of outcomes (10–19), and assembly of healthy nondonor controls for estimation of donation-attributable risks (20–25). The resulting evidence suggests small donation-related increases in the risk of kidney failure that have affected policy requirements and guidelines for the informed consent and care of living donors (26,27). Efforts to establish larger living donor consortia and registries with long-term follow-up are also being planned and pilot-tested (28,29).

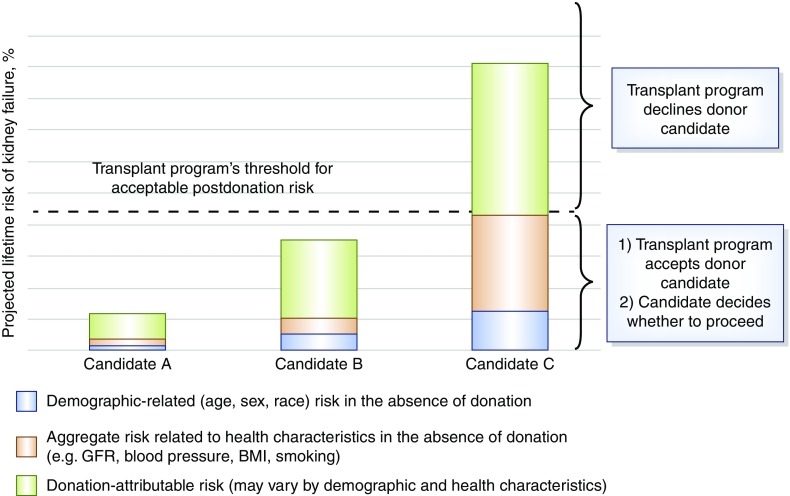

The recent 2017 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors focuses on risk assessment as a foundational theme. A central framework of the guideline is promotion of “consistent, transparent and defensible decision-making” on the basis of comparisons of individualized, quantitative estimates of donor risks “to a transplant program’s acceptable risk threshold” (Figure 1) (27). Although robust data necessary to ground risk thresholds for many outcomes are lacking, this conceptual framework provides a new structure for the consideration of available data by patients and providers, and a roadmap for design of future studies to address evidence gaps. Kidney donation is a decision with lifelong implications that can span dimensions of medical and psychosocial health. A new study found that “living kidney donors prioritized a range of outcomes, with the most important being kidney health and the surgical, lifestyle, functional, and psychosocial effects of donation” (30). In this review, we summarize the current state of evidence related to these outcomes important to donors, and suggest next steps to advance the evidence base for donor risk estimation and application with a transparent, consistent framework of shared decision-making.

Figure 1.

The KDIGO framework to accept or decline donor candidates compares projected lifetime risk of kidney (quantified as the aggregate of risk related to demographic and health profile and donation-attributable risks) to a transplant program's threshold of acceptable risk. Reproduced from reference 27, with permission.

Kidney Health

Assessment of living kidney donor values and perceptions at three centers in Australia and Canada by Hanson et al. (30) identified kidney function as the highest ranked outcome important to living donors, underpinned by fear of developing kidney failure. Although many donors felt they had ruled out the risk of kidney failure during evaluation, some were uncertain whether their glomerular filtration rate (GFR) after donation was “normal” and how to protect their long-term kidney function (e.g., by lifestyle or dietary modifications) (30). Similarly, a new study of 193 living kidney donors in the United States, assessed at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months postdonation, found that 21% (n=32) reported an emergence of anxiety about kidney injury or loss at one or more postdonation assessments, but this anxiety dissipated in 35% (11 out of 32) (31). In an interview-based study of 50 living donors at one center (assessed at a median 9 years after donation), 22% reported concern for failure of the remaining kidney before donation, whereas 12% endorsed this concern postdonation (32).

After donor nephrectomy there is compensatory hyperfiltration in the remaining kidney, such that the net reduction in GFR early after donation is only approximately 30% (25%–40%; i.e., decrement in GFR of 25–40 ml/min per 1.73 m2) (33–36). One long-term study of glomerular hemodynamics after kidney donation observed that the adaptive hyperfiltration mostly resulted from compensatory glomerular hypertrophy and hyperperfusion in the remaining kidney, rather than pathologic glomerular hypertension (37). In a prospective study of 182 predominantly (94.6%) white kidney donors and paired healthy nondonors, GFR measured by iohexol clearance declined 0.36 ml/min per year in nondonor controls but increased 1.47 ml/min per year in donors between 6 and 36 months of follow-up (33,35). The trajectory of change in GFR beyond 36 months postdonation, and associations with risk for ESKD, requires examination in larger, demographically diverse samples. A recent study of 2002 predominantly white living donors followed for up to 20 years at one center did not support an association of postdonation estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) trajectory and ESKD risk (38). Nevertheless, there is concern that adaptive hyperfiltration might result in faster progression of de novo kidney disease that could accelerate deterioration to low levels of kidney function or kidney failure (39).

Clinically important kidney end points include progression to advanced stages of CKD, injury markers such as proteinuria, and most importantly, ESKD. One study of 3956 predominantly white kidney donors found that 36% had eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (corresponding to CKD stage 3 or higher) at a median time of 9.2 years postdonation, and 2.6% had eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (corresponding to CKD stage 4 or higher) at a median of 23.9 years (40). Postdonation proteinuria was higher in men (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.56; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.18 to 2.05; P<0.001) and those with higher body mass index (BMI) (aHR, 1.10 per unit; P<0.001) (40). A meta-analysis found that after an average of 10 years of follow-up, 12% of donors had a GFR in the 30–59 ml/min range whereas only 0.2% had a GFR in the <30 ml/min range; further, most donors did not have a progressive GFR loss after the initial reduction postdonation (36). As in the general population, risk of kidney complications varies by baseline donor traits, such as race. For example, a study of 4650 donors in the United States found that by 7 years postdonation, after adjustment for age and sex, a greater proportion of black donors compared with white donors had kidney-related diagnoses: CKD (12.6% versus 5.6%; aHR, 2.32), proteinuria (5.7% versus 2.6%; aHR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.48 to 3.62), and nephrotic syndrome (1.3% versus 0.1%; aHR, 15.7; 95% CI, 2.97 to 83.0) (17).

Although the risk of ESKD after kidney donation does not exceed ESKD rates in the general population (41–43), two recent studies comparing donors with healthy nondonors for estimation of donation-attributable risk found that donation is associated with a small but significant increase in the risk of ESKD. In comparing 1901 kidney donors with 32,621 healthy, demographically matched controls in Norway, Mjøen et al. (22) found that nine donors (0.47%) developed ESKD versus 22 healthy nondonors (0.07%) (aHR, 11.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 4.4 to 29.6). On the basis of linking data for 96,217 living donors from the United States donor registry and healthy participants drawn from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III to national ESKD reporting forms, Muzaale et al. (21) reported that the cumulative incidence of ESKD at 15 years was 30.8 per 10,000 in donors compared with 3.9 per 10,000 in matched donors (risk attributable to donation of 26.9 per 10,000). Considered by race, black living donors had the highest absolute risk of ESKD postdonation as well as the highest risk attributable to donation. Although the risk increase is small, details have been debated (44), and absolute postdonation risk is low overall, these data have appropriately shaped informed consent policies in the interest of transparent disclosure, such that United States transplant programs are now required to disclose the possibility of donation-attributable increase in ESKD risk (26), and similar disclosure is recommended for international practice by the 2017 KDIGO guideline (27).

Some information is available on ESKD causes after donation. A linkage of national donor registry data to ESKD registry data for 125,427 living donors found that early postdonation ESKD was predominantly reported as due to glomerulnephritis (GN), whereas late postdonation ESKD was more frequently reported as due to diabetes or hypertensive kidney disease, the latter two consistent with the leading causes of ESKD in the United States general population (45). In a single-center study of 3956 predominantly white living donors, 48% of ESKD events with known causes (n=12 out of 25) were related to hypertension or diabetes (46). Although the pathways from predonation metabolic and genetic risk factors to postdonation ESKD are not yet well defined, these data emphasize the importance of careful evaluation to identify kidney risk factors, counseling regarding known and unknown risks, and engagement in postdonation follow-up, especially for higher-risk groups, so that any signs of early postdonation kidney problems can be recognized and managed.

To help ground a quantitative framework for living donor candidate evaluation, the 2017 KDIGO guideline development methodology included collaboration with the CKD Prognosis Consortium to develop a tool to project the 15-year and lifetime incidence of kidney failure in the absence of donation on the basis of demographic and health characteristics at the time of evaluation (47). The risk model uses meta-analysis of data from nearly 5,000,000 healthy persons identified from seven general population cohorts who are similar to kidney donor candidates, calibrated to annual ESKD incidence in the United States healthy population (47), and the resulting online tool is available online (www.transplantmodels.com). Projected ESKD risk was higher in the presence of a lower estimated GFR, higher albuminuria, hypertension, current or former smoking history, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. In the model-based lifetime projections, the risk of ESKD in the absence of donation was highest among persons in the youngest age group, particularly among young black men. Importantly, a central principle of the approach and tool is risk assessment on the basis of simultaneous consideration of a profile of demographic and clinical characteristics, rather than individual factors in isolation (e.g., risk related to high BP or BMI alone), and comparison of integrated risk to a threshold of acceptable risk (Figure 1).

Other tools are available. Using a cohort of 3956 white donors, Ibrahim et al. (40) developed a calculator for eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ESKD on the basis of risk relationships for older age (hazard ratio [HR], 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.09 P<0.001), higher BMI (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.13; P<0.001), and higher systolic BP (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.04; P=0.01). Another recent tool estimates postdonation risk on the basis of national United States registry and ESKD data for 133,824 living donors. ESKD risk after donation in this model is higher with male sex, black race, higher BMI, and biologic relationship to recipient (48). Because of the lack of available data, the model does not incorporate clinical or laboratory variables, such as the use of antihypertensive medications and urine albumin excretion. A key finding in this study was that although the 20-year predicted ESKD risk was very small in the average (median) donor (34 in 10,000), in a small subgroup of donors (1%) the risk was substantially higher than the median (256 in 10,000) (48). Recent studies of kidney outcomes in living donors, including ESKD, reduced GFR/CKD, and proteinuria, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of recent studies of kidney outcomes in living donors, according to risk perspective

| Author, yr | Data Source/Design | Outcome Measure and Follow-Up | Risk Perspective | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESKD | ||||

| Gibney et al. (87) Transplantation 2007 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1993–2005) and transplant waitlist registration data (1993–2005) for 8889 United States LKD | • Transplant waitlist registrations among prior LKD as a measure of ESKD | • Descriptive | • 102 LKD waitlisted at median 17.6 yr postdonation |

| • Between donors | • Among listed LKD, 44% were black (compared with 14% total black donors; P<0.0001) and 40% were white (compared with 14% total black donors; P<0.0001) | |||

| Ibrahim et al. (41) N Engl J Med 2009 | • Cohort study of 3698 LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1963–2007); 98% white race | • ESKD requiring dialysis or transplantation on the basis of the report of the LKD or recipient | • LKD versus general population | • 11 LKD developed ESKD, at an average of 22.5±10.4 yr (180 cases PMPY) |

| • ESKD in LKD did not exceed national ESRD rate for white Americans (268 cases PMPY) | ||||

| Cherikh et al. (88) Am J Transplant 2011 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1987–2003) and national kidney replacement treatment (1987–2009) for 56,458 United States LKD | • ESKD defined by CMS Medical Evidence Form 2728 | • LKD versus general population | • ESKD was significantly higher in black compared with white LKD: 0.423 versus 0.086 per 1000 yr at risk (RR, 4.92; P<0.05). |

| • Mean follow-up 9.8 yr | • ESKD in LKD did not exceed national reports for general United States population, by race (0.998 and 0.273 per 1000 for black and white Americans, respectively) | |||

| Mjøen et al. (22) Kidney Int 2014 | • Linkage of transplant registry data for 1901 Norwegian LKD with national kidney replacement treatment records | • ESKD reported in the national registry | • LKD versus healthy nondonors | • ESKD was higher among LKD compared with healthy nondonors (302 versus 100 PMPY; aHR, 11.38; P<0.001) |

| • Healthy controls from HUNT-1 survey (1984–1987) after screening for health exclusions to donation, then matched by demographic and clinical factors | • Median and maximum donor follow-up: 15.2 and 44 yr, respectively | |||

| • Median and maximum control follow-up: 25 and 26 yr, respectively | ||||

| Muzaale et al. (21) JAMA 2014 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1994–2011) and national kidney replacement treatment records for 96,217 United States LKD | • ESKD reported in national registries (initiation of maintenance dialysis, waitlist placement, or transplant) | • LKD versus healthy nondonors | • ESKD was higher among LKD compared with healthy nondonors (3.9 versus 30.8 per 10,000 over 15 yr; P<0.001) |

| • “Healthy” controls drawn from NHANES III, after screening for health exclusions to donation, then matched by demographic and clinical factors | • Median and maximum LKD follow-up, 7.6 and 15 yr, respectively | • Black LKD had highest cumulative incidence of ESKD and highest absolute risk increase (donation-attributable increase per 10,000 over 15 yr by race: 50.8 in black, 25.9 in Hispanic, and 22.9 in white LKD) | ||

| • Median and maximum control follow-up: 15 yr | ||||

| Ibrahim et al. (40) J Am Soc Nephrol 2016 | • Cohort study of 3956 white LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1963–2013) | • Composite of ESKD (on the basis of report of the LKD or recipient), or eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | • Between donors | • Cumulative incidence of ESKD per 10,000 at 15, 30, and 40 yr was 13.5, 68.7, and 78.7, respectively |

| • Mean and maximum follow-up: 16.6 and 51 yr, respectively | • Composite end point was associated with older age (aHR, 1.07 per yr; P<0.001), higher BMI (aHR, 1.08 per kg/m2; P<0.01), and higher systolic BP (aHR, 1.02 per mm Hg; P<0.01) at baseline. | |||

| Locke et al. (89) Kidney Int 2016 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1987–2013) and national kidney replacement treatment records for 119,769 United States LKD | • ESKD reported in national registries, as per (21) | • Between donors | • Cumulative incidence of ESKD at 20 yr was 93.9 per 10,000 in obese compared with 39.7 per 10,000 in nonobese LKD |

| • Median and maximum follow-up: 10.7 and 20 yr, respectively | • Covariate-adjusted ESKD risk was 86% higher in compared versus nonobese LDK (aHR, 1.86; P=0.04) | |||

| • Each 1-unit increase in BMI>27 kg/m2 was associated with 7% higher ESKD risk (aHR, 1.07; P=0.004) | ||||

| Anjum et al. (45) Am J Transplant 2016 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1987–2014) and national kidney replacement treatment records for 125,427 United States LKD | • ESKD reported in national registries, as per (21) | • Between donors | • Cumulative incidence of ESKD increased from 10 per 10,000 at 10 yr to 85 per 10,000 at 25 yr |

| • ESKD causes from CMS Medical Evidence Form 2728, categorized as hypertension/large vessel disease, diabetes, or GN | • Early (within 10 yr) postdonation ESKD was predominantly attributed to GN, whereas later predominantly reported as diabetic and hypertensive (later versus early IRR, 7.7 and 2.6, respectively) | |||

| • Median and maximum follow-up: 11 and 25 yr, respectively | • Time-dependent increase did not occur for GN (IRR, 0.7) | |||

| Massie et al. (48) J Am Soc Nephrol 2017 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1987–2015) and national kidney replacement treatment records for 133,842 United States LKD | • ESKD defined by the CMS Medical Evidence Form 2728 | • Between donors | • ESKD risk was significantly (P<0.01) higher with black race (aHR, 2.96), male sex (aHR, 1.88), higher BMI (aHR, 1.61 per 5 kg/m2), and first-degree relationship to recipient (aHR, 1.70) |

| • Among nonblack LKD, ESKD risk increased with older age (aHR, 1.40 per decade) | ||||

| • Among black LKD, older age was not significantly associated with ESKD risk (HR, 0.88; P=0.3) | ||||

| Matas et al. (46) Am J Transplant 2018 | • Cohort study of 4030 LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1963–2015) | • ESKD on the basis of the report of the LKD or recipient as in (41), or return to center | • Between donors | • 39 developed ESKD at mean of 27±9.8 yr |

| • Mean and maximum follow-up: 18.0 and 15 yr, respectively | • 48% of ESKD events with known causes (n=12/25) were attributed to hypertension or diabetes (alone or in combination) | |||

| Serrano et al. (90) Am J Transplant 2018 | • Cohort study of 3752 LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1975–2014); 98% white | • ESKD on the basis of the report of the LKD or recipient as in (41), or return to center | • Between donors | • No difference in ESKD at end of study in obese and nonobese donors (0.5% versus 0.6%; P=0.46) |

| • End of follow-up not reported | ||||

| Wainright et al. (91) Am J Transplant 2018 | • Linkage of OPTN LKD registration (1994–2016) and national kidney replacement treatment records for 123,526 United States LKD | • ESKD reported in national registries, as per (21) | • Between donors | • 218 developed ESKD, at a median of 11 yr |

| • Median follow-up: 10.3 yr | • ESKD risk was significantly (P<0.01) higher with male sex (aHR, 1.75), higher BMI (aHR, 1.34 per 5 kg/m2), first-degree relationship to recipient (aHR, 2.01), lower predonation eGFR (aHR, 0.89 per 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increase), and lower SES neighborhood at donation | |||

| • Among white LKD, ESKD risk increased with older age (aHR, 1.26 per decade) | ||||

| • Among black LKD, ESKD risk decreased with older age (aHR, 0.75 per decade) | ||||

| Reduced GFR/CKD, proteinuria, and other kidney complications | ||||

| Lentine et al. (10) N Engl J Med 2010 | • Linkage of OPTN data for 4650 LKD in 1987–2007 with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007 claims) | • CKD diagnosis over median 7.7 yr follow-up | • Descriptive | • Overall, CKD was reported in 5.2% at 5 yr |

| • Stage-specific CKD coding examined a subgroup of 2307 LKD | • Between donors | • Adjusted CKD risk was twice as likely among black (aHR, 2.32; P<0.001) or Hispanic (aHR, 1.90; P<0.001) compared with white LKD | ||

| • CKD stage 3 was higher in black (aHR, 3.60; P=0.009) or Hispanic (aHR, 4.2; P=0.006) versus white LKD | ||||

| Lentine et al. (15) Transplantation 2013 | • Linkage of OPTN data (starting 1987) with administrative billing claims for 4650 privately insured (2000–2007 claims) and 4007 Medicare-insured (2000–2008 claims) LKD | • CKD and proteinuria diagnoses | • Descriptive | • At 5 yr, CKD was reported in 5.2% of the privately insured and 21.8% of the Medicare-insured LKD, and proteinuria in 2% and 5%, respectively |

| • Median follow-up 7.7 yr for the privately insured and 6 yr for the Medicare-insured samples | • Between donors | • Adjusted CKD risk was higher for black LKD in the privately insured (aHR, 2.32; P<0.001) and Medicare (aHR, 1.84; P<0.001) samples | ||

| • Adjusted proteinuria risk was higher for black LKD in privately insured (aHR, 2.27; P<0.05) and Medicare (aHR, 2.44; P<0.001) samples | ||||

| Lentine et al. (17) Transplantation 2015 | • Linkage of OPTN data for 4650 LKD with private insurance medical claims, as above (10) | • CKD diagnosis over median 7.7 yr follow-up | • Descriptive | • At 7 yr, significantly more (P<0.05) black compared with white LKD had kidney condition diagnoses: CKD (12.6% versus 5.6%; aHR, 2.32), proteinuria (5.7% versus 2.6%; aHR, 2.27), nephrotic syndrome, (1.3% versus 0.1%; aHR, 15.7), and any kidney condition (14.9% versus 9.0%; aHR, 1.72) |

| • Between donors | ||||

| Kasiske et al. (35) Am J Kidney Dis 2015 | • Prospective study of 182 LKD (94.6% white) | • GFR measured by plasma iohexol clearance, from 6 to 30 mo postdonation | • LKD versus healthy nondonors | • GFR declined 0.36±7.55 ml/min per yr in controls but increased 1.47±5.02 ml/min per yr in LKD (P for difference in change =0.005) |

| • Paired controls meeting donor selection criteria | • Proteinuria and albuminuria | • Albuminuria increased modestly in LKD (3.6–4.2 mg/g) but not in controls (4.7–4.7 mg/g) (P for difference in change <0.001) | ||

| • Proteinuria did not increase in LKD or controls | ||||

| Ibrahim et al. (40) J Am Soc Nephrol 2016 | • Cohort study of 3956 white LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1963–2013) | • Urinary AER >30 mg/g | • Between donors | • Proteinuria was identified in 6.1% at median 18 yr |

| Creatinine, 24-h urinary protein >200 mg/d, ≥2+on urine dipstick tests, self-report | • Proteinuria was associated with higher BMI (aHR, 1.10 per kg/m2; P<0.001) and male sex (aHR, 1.56; P<0.01), and less common in donors related to their recipient (aHR, 0.58; P=0.03) | |||

| • Mean and maximum follow-up: 16.6 and 51 yr, respectively | ||||

| Matas et al. (38) Am J Transplant 2018 | • Cohort study of 2002 white LKD at one center in Minnesota, United States (1990–2014) | • eGFR by CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation | • Between donors | • Average eGFR increased steadily until donors reached age 70 yr: 1.12 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr between 6 wk and 5 yr postdonation, 0.24 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr between 5 and 10 yr postdonation, and 0.07 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr between 10 and 20 yr postdonation |

| • Donors contacted at 6, 12, 24, and 36 mo, then every 3 yr | • After age 70, eGFR declined | |||

| • Includes request to contact local clinics for laboratory tests | • eGFR trajectories did not explain ESKD risk | |||

Adapted and updated from reference 7, with permission. OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; LKD, living kidney donors; PMPY, per million per year; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; RR, relative risk; HUNT-1, Nord-Trøndelag Health Study; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; GN, glomerulonephritis; BMI, body mass index; IRR, incidence rate ratio; HR, hazard ratio; SES, socioeconomic status; AER, albumin excretion rate.

Surgical Risks

In the study by Hanson et al. (30), avoiding catastrophic consequences such as surgical mortality and morbidity was important to donors, particularly during decision-making, because they were the “most serious” outcomes and would also affect their family. Some participants ranked time to recovery, surgical complications, and pain highly because they felt “deeply disappointed” and “resentful” about enduring a more debilitating and protracted recovery than they had been “led to expect.” (30) In a multicenter, prospective study of 228 living donors, perioperative complications, not surprisingly, were associated with clinically and statically significant reductions in measures of health-related quality of life (49). Other studies have noted that a minority of donors have reported slower than expected recovery (50). However, aside from capture of length of initial hospital stay and time to return to work in some clinical trials (typically comparisons of different operative techniques) (51,52) and single-center reports, data on postdonation recovery are not systematically captured.

Fortunately, the risk of morbidity and mortality after living donor nephrectomy is low. A United States study linking the national donor registry for 80,347 donors to the Social Security Death Master Index reported the 90-day mortality to be 3.1 per 10,000 (20). Consistent rates have also been reported in other studies (53). Administrative data have been used to identify perioperative complications in large samples of living kidney donors, independent of center or surgeon reporting. Using a composite outcome of cardiac, respiratory, digestive, urinary, procedural, hemorrhage, or infectious complications, one United States study estimated the incidence of perioperative complications as 7.9% and noted a decrease over time, from 10.1% in 1998 to 7.6% in 2010 (54). Limitations of this study include the lack of confirmation of donor status through patient-level linkages to the national registry, and use of weighting schemes to draw inferences for a “represented” sample of all United States donors on the basis of a stratified sample of 20% of acute care hospitalizations (55). A subsequent study integrated national United States donor registry data as a source of verified living donor status with administrative records from a consortium of 98 academic hospitals (2008–2012, n=14,964). In this study, 16.8% of donors experienced any perioperative complication, most commonly gastrointestinal (4.4%), bleeding (3.0%), respiratory (2.5%), and surgical/anesthesia-related injuries (2.4%) (18). Major complications, defined as Clavien grading system for surgical complications level 4 or 5 (56), affected 2.5% of donors. Similarly, a Norwegian registry-based study of 1022 living kidney donations performed between 1997 and 2008 reported 18% minor and 2.9% major complications by Clavien grading (57). The 2017 KDIGO guideline and the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Transplantation: Update 2018 present these estimates as information for donor counseling (27,58). Given the low incidence of major perioperative complications, estimates for predonation characteristics that alter the risk are imprecise. Efforts to capture granular complications data, such as through large, national registries, including development and validation of patient-centered recovery measures, are needed to support contemporary estimates of the risk of perinephrectomy complications according to an individualized profile of predonation characteristics (27).

Psychosocial Outcomes

Quality of Life

Although living donors derive no personal medical benefit from donation, they may experience psychosocial benefits related to the altruistic act of improving the health and wellbeing of another person. A systematic review assessing psychosocial health in living kidney donors found that the majority of donors scored high on health-related quality-of-life measurements (59). Psychosocial health was unchanged or improved after donation and overall, and was similar or better than the general population. A minority of donors experienced negative psychosocial outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and lower-quality relationships. Reassuringly, most donors did not regret their decision to donate and would undergo the process again, even in the rare circumstances when the recipient experiences a poor outcome (9). However, recipient graft loss and death have been associated with increased risk of depression treatment after donation in some studies (12).

Recently, Rodrigue et al. (31) reported on psychosocial measures assessed pre- and postdonation among 193 living kidney donors and 20 healthy controls. Donors experience minimal to no dysfunction in mood, body image, fear of kidney failure, life satisfaction, and decisional stability up to 2 years postdonation, and their outcomes did not differ significantly from the healthy nondonor controls. The overall incidence of new-onset mood disturbance (16%), fear of kidney failure (21%), body image concerns (13%), and life dissatisfaction (10%) after donation was low. Donors with preexisting concerns were at the highest risk of the same outcomes postdonation. Thus, although donors have generally favorable psychosocial outcomes postdonation, the small risk of adverse psychosocial functioning should be discussed with all living kidney donor candidates.

Financial Risks

Although the study by Hanson et al. (30) found that some donors had financial assistance to help them absorb out-of-pocket expenses and replace lost income as a result of donation, other participants ranked financial concerns highly because they believed that lost income and out-of-pocket expenses were unfair barriers to donors. For younger donors, single parents, and one donor who was not a resident and uninsured, the costs were “a big hit” and, for one, “an absolute destruction.” (30) The leave required for recovery caused some donors to lose their jobs (30). A recent survey of 51 United States donors found that perceived financial burden was highest among those with predonation cost concerns and with an income <$60,000 (60).

Although it is widely accepted that living donation should be a financially neutral act, unfortunately, financial risks are a reality in current practice. Even in countries where the donation-related medical expenses are paid by the recipient’s insurance or the health care system, it has been documented that donor candidates may incur many types of direct and indirect costs in the donation process, including for travel, medications, lost time from work, and dependent care (61–63). In one United States study, 92% of living kidney donors incurred direct costs (median $433, range $6–$10,240) and more than one third (36%) reported lost wages in the first year after donation (median $2712, range $546–$19,728) (62). Similarly, a multicenter, Canadian cohort found that 98% of living kidney donors incurred donation-related costs, with median (seventh percentile) out-of-pocket costs of $1254 ($2598) (Canadian dollars); among 30% who experienced unpaid time off work, median lost income was $5534, and total costs exceeded $5500 in 25% of the cohort (64). A single-center, retrospective survey of living donors who were working for compensation at the time of donation (2005–2015) found that increased length of time to return to work was a significant predictor of financial burden, and that donors in manual/skilled trade occupations experienced greatest financial burden for each week away from work (65). Older age at donation and nondirected (versus directed) donation were associated with significantly decreased financial burden (65). Living donation may also affect ability to obtain life, disability, and health insurance (66–68).

The National Organ Transplant Act has been clarified, to explicitly state that “reasonable payments associated with… the expenses of travel, housing, and lost wages incurred by the donor” are legal (69). Many states have enacted legislation to offer tax deductions or credits, or other benefits, to living organ donors (70). These programs vary state by state, are underused, and have not been studied with regard to effect on financial burden of donation. Trials of replacement of lost wages in the donation process are being pilot-tested (71,72).

A 2016 convenience sample of informed consent forms for living donor and transplant candidate evaluation from nine geographically diverse programs in the United States identified misconceptions about defraying donation-related costs, reinforced by ambiguous language or omissions in the donor informed consent documents (73). Living donor candidates should receive counseling about financial costs and risks before donation, information about the availability of legal cost replacement programs, and assistance in accessing legitimate cost replacement programs. In 2016, the American Society of Transplantation launched an online financial toolkit to help donor candidates learn about the finances of being a living organ donor; this dynamic resource will be expanded and updated over time (74). An American Society of Transplantation Living Donor Community of Practice work group has developed guidance to help transplant centers maximize donor coverage and minimize financial consequences to donors (75).

Summary and Future Directions

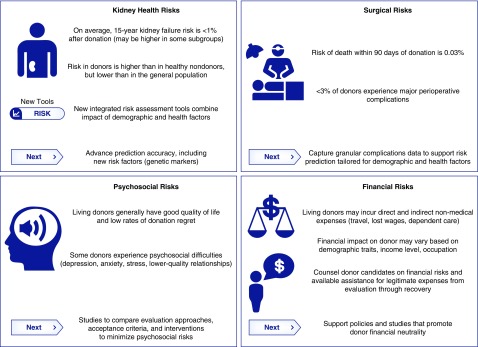

The practice of living donation relies on the ethical principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence (where the benefits to the recipient are great whereas the risks to the donor are justifiably low) as well as donor autonomy after informed consent (where risks and uncertainties are fully disclosed) (76). Understanding risks related to kidney health, surgical complications, and psychosocial outcomes is vital for donors and their care providers, and defining knowns and unknowns can inform future research and policy development priorities (Figure 2). However, focus on these key outcomes important to donors is not intended to be comprehensive, and other outcomes (e.g., pregnancy risks, hypertension, metabolic conditions, and effect on relationships, family dynamics, and lifestyle) are discussed elsewhere (13,14,19,24,77–85). Some adverse outcomes may only be fully appreciated after decades of follow-up of large cohorts of donors with diverse demographic characteristics. Ongoing commitment to strengthen the evidence base for donor candidate evaluation, selection, and counseling, including longer follow-up in representative cohorts, well designed use of integrated data sources (55), long-term registries (28), and advancement of tools for tailored risk estimation (7,47,76,86,49), should remain a leading priority for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

Figure 2.

Applying knowledge on outcomes important to donors can inform current counseling and next steps for research and policy. Infographic prepared for this perspective by Heather Hunt, JD, in collaboration with Alvin Thomas, MSPH.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Heather Hunt, JD, and Alvin Thomas, MSPH, collaborated in preparing the original infographic for this article and grant permission for its use. Ms. Hunt is president of LIVE ON Organ Donation, Inc., a nonprofit organization that raises money to support living organ donors’ nonmedical expenses, and is vice chair of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Living Donor Committee. Mr. Thomas is a student in the Department of Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Commentary, “Commentary on Risks of Living Kidney Donation: Current State of Knowledge on Core Outcomes Important to Donors,” on pages 609–610.

References

- 1.OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network)/UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing): National Data Reports, Donors Recovered in the U.S. by Donor Type, Latest Data. Available at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/. Accessed July 27, 2018

- 2.Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation: Kidney Transplants (Year 2016). Available at: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/countkidney/. Accessed August 18, 2018

- 3.Gordon EJ: Living organ donors’ stories: (unmet) Expectations about informed consent, outcomes, and care. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2: 1–6, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ommen ES, Winston JA, Murphy B: Medical risks in living kidney donors: Absence of proof is not proof of absence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 885–895, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lentine KL, Patel A: Risks and outcomes of living donation. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 19: 220–228, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentine KL, Segev DL: Health outcomes among non-caucasian living kidney donors: Knowns and unknowns. Transpl Int 26: 853–864, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lentine KL, Segev DL: Understanding and communicating medical risks for living kidney donors: A matter of perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 12–24, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross CR, Messersmith EE, Hong BA, Jowsey SG, Jacobs C, Gillespie BW, Taler SJ, Matas AJ, Leichtman A, Merion RM, Ibrahim HN; RELIVE Study Group: Health-related quality of life in kidney donors from the last five decades: Results from the RELIVE study. Am J Transplant 13: 2924–2934, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens K, Boudville N, Dew MA, Geddes C, Gill JS, Jassal V, Klarenbach S, Knoll G, Muirhead N, Prasad GV, Storsley L, Treleaven D, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: The long-term quality of life of living kidney donors: A multicenter cohort study. Am J Transplant 11: 463–469, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Saab G, Salvalaggio PR, Axelrod D, Davis CL, Abbott KC, Brennan DC: Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 363: 724–732, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Davis CL, Axelrod D, Abbott KC, Salvalaggio PR, Burroughs TE, Saab G, Brennan DC: Associations of recipient illness history with hypertension and diabetes after living kidney donation. Transplantation 91: 1227–1232, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Davis CL, McCabe M, Brennan DC, Leander S, Garg AX, Waterman AD: Depression diagnoses after living kidney donation: Linking U.S. Registry data and administrative claims. Transplantation 94: 77–83, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentine KL, Vijayan A, Xiao H, Schnitzler MA, Davis CL, Garg AX, Axelrod D, Abbott KC, Brennan DC: Cancer diagnoses after living kidney donation: Linking U.S. Registry data and administrative claims. Transplantation 94: 139–144, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Brennan DC, Segev DL: Understanding antihypertensive medication use after living kidney donation through linked national registry and pharmacy claims data. Am J Nephrol 40: 174–183, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Garg AX, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Brennan DC, Segev DL: Consistency of racial variation in medical outcomes among publicly and privately insured living kidney donors. Transplantation 97: 316–324, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, Leander SE, Brennan DC, Taler SJ, Axelrod D, Segev DL: Gender differences in use of prescription narcotic medications among living kidney donors. Clin Transplant 29: 927–937, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Brennan DC, Segev DL: Race, relationship and renal diagnoses after living kidney donation. Transplantation 99: 1723–1729, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Axelrod D, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, Dzebisashvili N, Schold JD, Brennan DC, Randall H, King EA, Segev DL: Perioperative complications after living kidney donation: A national study. Am J Transplant 16: 1848–1857, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Schnitzler MA, Hess GP, Kasiske BL, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Garg AX, Schold JD, Randall H, Dzebisashvili N, Brennan DC, Segev DL: Predonation prescription opioid use: A novel risk factor for readmission after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant 17: 744–753, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, McBride MA, Montgomery RA: Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 303: 959–966, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang M-C, Montgomery RA, McBride MA, Wainright JL, Segev DL: Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA 311: 579–586, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, Foss A, Midtvedt K, Øyen O, Reisæter A, Pfeffer P, Jenssen T, Leivestad T, Line PD, Øvrehus M, Dale DO, Pihlstrøm H, Holme I, Dekker FW, Holdaas H: Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 86: 162–167, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg AX, Nevis IF, McArthur E, Sontrop JM, Koval JJ, Lam NN, Hildebrand AM, Reese PP, Storsley L, Gill JS, Segev DL, Habbous S, Bugeja A, Knoll GA, Dipchand C, Monroy-Cuadros M, Lentine KL; DONOR Network: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 372: 124–133, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam NN, McArthur E, Kim SJ, Prasad GV, Lentine KL, Reese PP, Kasiske BL, Lok CE, Feldman LS, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research DONOR Network: Gout after living kidney donation: A matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 925–932, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam N, Huang A, Feldman LS, Gill JS, Karpinski M, Kim J, Klarenbach SW, Knoll GA, Lentine KL, Nguan CY, Parikh CR, Prasad GV, Treleaven DJ, Young A, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Acute dialysis risk in living kidney donors. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3291–3295, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing: Policy 14: Living Donation, 2018. Available at: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/. Accessed July 27, 2018

- 27.Lentine KL, Kasiske BL, Levey AS, Adams PL, Alberú J, Bakr MA, Gallon L, Garvey CA, Guleria S, Li PK, Segev DL, Taler SJ, Tanabe K, Wright L, Zeier MG, Cheung M, Garg AX: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 101[Suppl 1]: S1–S109, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasiske BL, Asrani SK, Dew MA, Henderson ML, Henrich C, Humar A, Israni AK, Lentine KL, Matas AJ, Newell KA, LaPointe Rudow D, Massie AB, Snyder JJ, Taler SJ, Trotter JF, Waterman AD; Living Donor Collective Participants: The living donor collective: A scientific registry for living donors. Am J Transplant 17: 3040–3048, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwelack B, Wörmann V, Berger K, Gerß J, Wolters H, Vitinius F, Burgmer M; German SoLKiD Consortium: Investigation of the physical and psychosocial outcomes after living kidney donation - a multicenter cohort study (SoLKiD - safety of Living Kidney Donors). BMC Nephrol 19: 83, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanson CS, Chapman JR, Gill JS, Kanellis J, Wong G, Craig JC, Teixeira-Pinto A, Chadban SJ, Garg AX, Ralph AF, Pinter J, Lewis JR, Tong A: Identifying outcomes that are important to living kidney donors: A nominal group technique study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 916–926, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, Katz D, Jones J, Kaplan B, Fleishman A, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA; KDOC Study Group: Mood, body image, fear of kidney failure, life satisfaction, and decisional stability following living kidney donation: Findings from the KDOC study. Am J Transplant 18: 1397–1407, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruck JM, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Henderson ML, Massie AB, Segev DL: Interviews of living kidney donors to assess donation-related concerns and information-gathering practices. BMC Nephrol 19: 130, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasiske BL, Anderson-Haag T, Ibrahim HN, Pesavento TE, Weir MR, Nogueira JM, Cosio FG, Kraus ES, Rabb HH, Kalil RS, Posselt AA, Kimmel PL, Steffes MW: A prospective controlled study of kidney donors: Baseline and 6-month follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 577–586, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pabico RC, McKenna BA, Freeman RB: Renal function before and after unilateral nephrectomy in renal donors. Kidney Int 8: 166–175, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasiske BL, Anderson-Haag T, Israni AK, Kalil RS, Kimmel PL, Kraus ES, Kumar R, Posselt AA, Pesavento TE, Rabb H, Steffes MW, Snyder JJ, Weir MR: A prospective controlled study of living kidney donors: Three-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 114–124, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg AX, Muirhead N, Knoll G, Yang RC, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Housawi A, Boudville N; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Proteinuria and reduced kidney function in living kidney donors: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Kidney Int 70: 1801–1810, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenihan CR, Busque S, Derby G, Blouch K, Myers BD, Tan JC: Longitudinal study of living kidney donor glomerular dynamics after nephrectomy. J Clin Invest 125: 1311–1318, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matas AJ, Vock DM, Ibrahim HN: GFR ≤25 years postdonation in living kidney donors with (vs. without) a first-degree relative with ESRD. Am J Transplant 18: 625–631, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller PL, Rennke HG, Meyer TW: Glomerular hypertrophy accelerates hypertensive glomerular injury in rats. Am J Physiol 261: F459–F465, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahim HN, Foley RN, Reule SA, Spong R, Kukla A, Issa N, Berglund DM, Sieger GK, Matas AJ: Renal function profile in white kidney donors: The first 4 decades. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2885–2893, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, Gross CR, Matas AJ: Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 360: 459–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Dunér F, Brink B, Tydén G, Elinder CG: No evidence of accelerated loss of kidney function in living kidney donors: Results from a cross-sectional follow-up. Transplantation 72: 444–449, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fournier C, Pallet N, Cherqaoui Z, Pucheu S, Kreis H, Méjean A, Timsit MO, Landais P, Legendre C: Very long-term follow-up of living kidney donors. Transpl Int 25: 385–390, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill JS, Tonelli M: Understanding rare adverse outcomes following living kidney donation. JAMA 311: 577–579, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anjum S, Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Bae S, Luo X, Grams ME, Lentine KL, Garg AX, Segev DL: Patterns of end-stage renal disease caused by diabetes, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis in live kidney donors. Am J Transplant 16: 3540–3547, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matas AJ, Berglund DM, Vock DM, Ibrahim HN: Causes and timing of end-stage renal disease after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant 18: 1140–1150, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grams ME, Sang Y, Levey AS, Matsushita K, Ballew S, Chang AR, Chow EK, Kasiske BL, Kovesdy CP, Nadkarni GN, Shalev V, Segev DL, Coresh J, Lentine KL, Garg AX; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium: Kidney-failure risk projection for the living kidney-donor candidate. N Engl J Med 374: 411–421, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massie AB, Muzaale AD, Luo X, Chow EKH, Locke JE, Nguyen AQ, Henderson ML, Snyder JJ, Segev DL: Quantifying postdonation risk of ESRD in living kidney donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2749–2755, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hosseini K, Omorou AY, Hubert J, Ngueyon Sime W, Ladriere M, Guillemin F: Nephrectomy complication is a risk factor of clinically meaningful decrease in health utility among living kidney donors. Value Health 20: 1376–1382, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Rodrigue JR, Vishnevsky T, Fleishman A, Brann T, Evenson AR, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA: Patient-reported outcomes following living kidney donation: A single center experience. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 22: 160–168, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson CH, Sanni A, Rix DA, Soomro NA: Laparoscopic versus open nephrectomy for live kidney donors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD006124, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan H, Liu L, Zheng S, Yang L, Pu C, Wei Q, Han P: The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic donor nephrectomy for renal transplantation: An updated meta-analysis. Transplant Proc 45: 65–76, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matas AJ, Bartlett ST, Leichtman AB, Delmonico FL: Morbidity and mortality after living kidney donation, 1999-2001: Survey of United States transplant centers. Am J Transplant 3: 830–834, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schold JD, Goldfarb DA, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, Mandelbrot DA, Heaphy EL, Fatica RA, Poggio ED: Comorbidity burden and perioperative complications for living kidney donors in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1773–1782, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lentine KL, Segev DL: Better understanding live donor risk through big data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1645–1647, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M: The clavien-dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg 250: 187–196, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mjøen G, Øyen O, Holdaas H, Midtvedt K, Line PD: Morbidity and mortality in 1022 consecutive living donor nephrectomies: Benefits of a living donor registry. Transplantation 88: 1273–1279, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodríguez Faba O, Boissier R, Budde K, Figueiredo A, Taylor CF, Hevia V, Lledó García E, Regele H, Zakri RH, Olsburgh J, Breda A: European association of urology guidelines on renal transplantation: Update 2018. Eur Urol Focus 4: 208–215, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wirken L, van Middendorp H, Hooghof CW, Rovers MM, Hoitsma AJ, Hilbrands LB, Evers AW: The course and predictors of health-related quality of life in living kidney donors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant 15: 3041–3054, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruck JM, Holscher CM, Purnell TS, Massie AB, Henderson ML, Segev DL: Factors associated with perceived donation-related financial burden among living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 18: 715–719, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Yang RC, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors-a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1952–1960, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, Katz D, Jones J, Kaplan B, Fleishman A, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA; KDOC Study Group: Predonation direct and indirect costs incurred by adults who donated a kidney: Findings from the KDOC study. Am J Transplant 15: 2387–2393, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, Caulfield T, Boudville N, Prasad GV, Karpinski M, Storsley L, Treleaven D, Arnold J, Cuerden M, Jacobs P, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: A Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant 14: 916–922, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Przech S, Garg AX, Arnold JB, Barnieh L, Cuerden MS, Dipchand C, Feldman L, Gill JS, Karpinski M, Knoll G, Lok C, Miller M, Monroy M, Nguan C, Prasad GVR, Sarma S, Sontrop JM, Storsley L, Klarenbach S; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Financial costs incurred by living kidney donors: A prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2847–2857, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Larson DB, Wiseman JF, Vock DM, Berglund DM, Roman AM, Ibrahim HN, Matas AJ: Financial burden associated with time to return to work after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant 19: 204–207, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang RC, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Insurability of living organ donors: A systematic review. Am J Transplant 7: 1542–1551, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang RC, Young A, Nevis IF, Lee D, Jain AK, Dominic A, Pullenayegum E, Klarenbach S, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Life insurance for living kidney donors: A Canadian undercover investigation. Am J Transplant 9: 1585–1590, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boyarsky BJ, Massie AB, Alejo JL, Van Arendonk KJ, Wildonger S, Garonzik-Wang JM, Montgomery RA, Deshpande NA, Muzaale AD, Segev DL: Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant 14: 2168–2172, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lapointe Rudow D, Cohen D: Practical approaches to mitigating economic barriers to living kidney donation for patients and programs. Curr Transpl Rep 4: 24–31, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lacetera N, Macis M, Stith SS: Removing financial barriers to organ and bone marrow donation: The effect of leave and tax legislation in the U.S. J Health Econ 33: 43–56, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hays R: Informed consent of living kidney donors: Pitfalls and best practices. Curr Transplant Rep 2: 29–34, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodrigue JR, Fleishman A, Carroll M, Evenson AR, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA, Baliga P, Howard DH, Schold JD: The living donor lost wages trial: Study rationale and protocol. Curr Transplant Rep 5: 45–54, 2018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mittelman M, Thiessen C, Chon WJ, Clayville K, Cronin DC, Fisher JS, Fry-Revere S, Gross JA, Hanneman J, Henderson ML, Ladin K, Mysel H, Sherman LA, Willock L, Gordon EJ: Miscommunicating NOTA can Be costly to living donors. Am J Transplant 17: 578–580, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.American Society of Transplantation: Live Donor Toolkit: Resources for Those Consdiering Live Donation - Financial Toolkit, 2017. Available at: http://www.livedonortoolkit.com/financial-toolkit. Accessed July 30, 2018

- 75.Tietjen A, Hays R, McNatt G, Howey R, Lebron-Banks U, Thomas CP, Lentine KL: Billing for living kidney donor care: Balancing cost recovery, regulatory compliance, and minimized donor burden. Curr Transplant Rep 2019, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thiessen C, Gordon EJ, Reese PP, Kulkarni S: Development of a donor-centered approach to risk assessment: Rebalancing nonmaleficence and autonomy. Am J Transplant 15: 2314–2323, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lam NN, Garg AX, Segev DL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Brennan DC, Kasiske BL, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Lentine KL: Gout after living kidney donation: Correlations with demographic traits and renal complications. Am J Nephrol 41: 231–240, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garg AX, McArthur E, Lentine KL; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 372: 1469–1470, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garg AX, Pouget J, Young A, Huang A, Boudville N, Hodsman A, Adachi JD, Leslie WD, Cadarette SM, Lok CE, Monroy-Cuadros M, Prasad GV, Thomas SM, Naylor K, Treleavan D; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Fracture risk in living kidney donors: A matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 770–776, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garg AX, Meirambayeva A, Huang A, Kim J, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Boudville N, Lok C, McFarlane P, Karpinski M, Storsley L, Klarenbach S, Lam N, Thomas SM, Dipchand C, Reese P, Doshi M, Gibney E, Taub K, Young A; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research Network: Cardiovascular disease in kidney donors: Matched cohort study. BMJ 344: e1203, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Slinin Y, Brasure M, Eidman K, Bydash J, Maripuri S, Carlyle M, Ishani A, Wilt TJ: Long-term outcomes of living kidney donation. Transplantation 100: 1371–1386, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, Yang RC, Karley ML, Boudville N, Ramesh Prasad GV, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network: Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: A systematic review. Am J Transplant 6: 2965–2977, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ralph AF, Butow P, Hanson CS, Chadban SJ, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Kanellis J, Luxton G, Tong A: Donor and recipient views on their relationship in living kidney donation: Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 602–616, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thys K, Schwering KL, Siebelink M, Dobbels F, Borry P, Schotsmans P, Aujoulat I, Donation EPO; ELPAT Pediatric Organ Donation and Transplantation Working Group: Psychosocial impact of pediatric living-donor kidney and liver transplantation on recipients, donors, and the family: A systematic review. Transpl Int 28: 270–280, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lam NN, Lentine KL, Levey AS, Kasiske BL, Garg AX: Long-term medical risks to the living kidney donor. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 411–419, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Steiner RW: Risk appreciation for living kidney donors: Another new subspecialty? Am J Transplant 4: 694–697, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gibney EM, King AL, Maluf DG, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Living kidney donors requiring transplantation: Focus on african Americans. Transplantation 84: 647–649, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cherikh WS, Young CJ, Kramer BF, Taranto SE, Randall HB, Fan PY: Ethnic and gender related differences in the risk of end-stage renal disease after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant 11: 1650–1655, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Locke JE, Reed RD, Massie A, MacLennan PA, Sawinski D, Kumar V, Mehta S, Mannon RB, Gaston R, Lewis CE, Segev DL: Obesity increases the risk of end-stage renal disease among living kidney donors. Kidney Int 91: 699–703, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Serrano OK, Sengupta B, Bangdiwala A, Vock DM, Dunn TB, Finger EB, Pruett TL, Matas AJ, Kandaswamy R: Implications of excess weight on kidney donation: Long-term consequences of donor nephrectomy in obese donors. Surgery 164: 1071–1076, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wainright JL, Robinson AM, Wilk AR, Klassen DK, Cherikh WS, Stewart DE: Risk of ESRD in prior living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 18: 1129–1139, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]