Abstract

Purpose: We developed a polycaprolactone (PCL) co-delivery implant that achieves zero-order release of 2 ocular hypotensive agents, timolol maleate and brimonidine tartrate. We also demonstrate intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering effects of the implant for 3 months in vivo.

Methods: Two PCL thin-film compartments were attached to form a V-shaped co-delivery device using film thicknesses of ∼40 and 20 μm for timolol and brimonidine compartments, respectively. In vitro release kinetics were measured in pH- and temperature-controlled fluid chambers. Empty or drug-loaded devices were implanted intracamerally in normotensive rabbits for up to 13 weeks with weekly measurements of IOP. For ocular concentrations, rabbits were euthanized at 4, 8, or 13 weeks, aqueous fluid was collected, and ocular tissues were dissected. Drug concentrations were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.

Results: In vitro studies show zero-order release kinetics for both timolol (1.75 μg/day) and brimonidine (0.48 μg/day) for up to 60 days. In rabbit eyes, the device achieved an average aqueous fluid concentration of 98.1 ± 68.3 ng/mL for timolol and 5.5 ± 3.6 ng/mL for brimonidine. Over 13 weeks, the drug-loaded co-delivery device resulted in a statistically significant cumulative reduction in IOP compared to untreated eyes (P < 0.05) and empty-device eyes (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: The co-delivery device demonstrated a zero-order release profile in vitro for 2 hypotensive agents over 60 days. In vivo, the device led to significant cumulative IOP reduction of 3.4 ± 1.6 mmHg over 13 weeks. Acceptable ocular tolerance was seen, and systemic drug levels were unmeasurable.

Keywords: drug delivery systems, glaucoma, timolol, brimonidine, co-delivery, controlled release

Introduction

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide.1 While glaucoma is most commonly treated with hypotensive eye drops to control intraocular pressure (IOP), the barriers to patient compliance are well documented2–4 with noncompliance to prescribed eye drops among glaucoma patients of 20%–60%.2,5–7

To circumvent problems with topical eye drop therapies, there has been substantial effort in developing a sustained release formulation for glaucoma therapy. For example, delivery of timolol maleate or brimonidine tartrate has been explored in the forms of microspheres,8–10 nanovesicles,11 ocular inserts,12 contact lenses,13 and others. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that sustained release of dorzolamide by biodegradable microparticles not only reduced IOP in normotensive rabbits14 but also decreased glaucomatous retinal ganglion cell loss in a rat disease model of glaucoma.15 We have also previously demonstrated that biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) intracameral devices delivering a prostaglandin analog16,17 attained over 5 months of IOP reduction in normotensive rabbits.16 Compared to topical administration, intracameral PCL implants have the advantage of bypassing the corneal epithelial barrier, increasing the amount of drug delivered to the target tissues. The PCL reservoir-based systems can also achieve longer periods of sustained, zero-order release due to increased total amount of drug payload, as well as better control over the diffusive polymer barrier compared to particles that can exhibit burst release due to more rapid degradation.17,18

Simultaneous long-term delivery of multiple glaucoma agents would offer an advance in patient treatment. Managing glaucoma with 2 or more agents for additive or synergistic IOP reduction is common practice, for which a number of topical drug combination formulations have been developed, such as Combigan® (Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) combining timolol maleate and brimonidine tartrate, and CosoptPF® (Akorn, Lake Forest, IL), combining dorzolamide HCl and timolol maleate. For sustained release devices, effectively delivering multiple agents can be challenging, because different drugs often require tailored release rates. We optimized the thickness of diffusion-limiting PCL films to achieve independent controlled release rates of timolol maleate and brimonidine tartrate using a single device. In this study, we report the design and characterization of a co-delivery implant, demonstrating customizable zero-order release kinetics of both drugs. We also show pharmacokinetic profiles of co-delivery devices in vivo and cumulative reduction in IOP in vivo using a normotensive rabbit model.

Methods

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) unless noted otherwise. Brimonidine tartrate was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Device fabrication

Devices were fabricated as previously described.17 Briefly, PCL (Mn = 80 kDa) was dissolved in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol at a concentration of 150 mg/mL, spun-cast on a silicon wafer at 1000 rpm, and then annealed at 110°C. To achieve the desired drug release rate of timolol and brimonidine, respectively, the film thickness was tuned for each drug compartment. Film thickness was measured using a film micrometer (iGaging, San Clemente, CA). The casting process resulted in a ∼20 μm thick film, which was used for fabricating the brimonidine compartment. The casting process was repeated to achieve a double layer of ∼40 μm thickness, which was used to fabricate the timolol compartment.

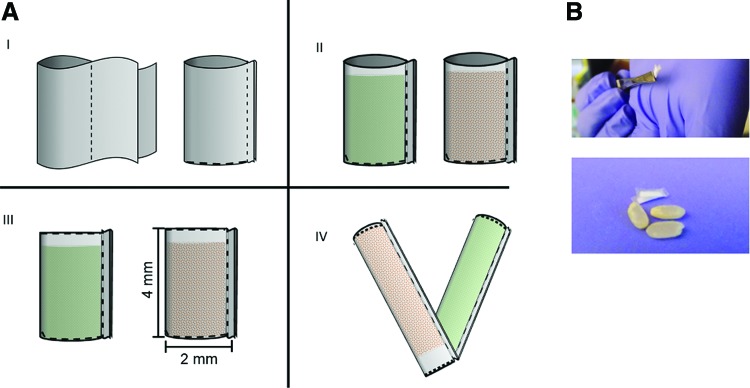

To make each compartment, spun-cast PCL thin films with the desired thickness were folded in half and heat sealed by applying current to a nichrome wire, selectively heating the edges (Fig. 1, dotted lines) to form a pocket. Approximately 1 mg of lyophilized timolol or brimonidine powder was loaded into the pocket and heat sealed, creating a closed compartment. Each compartment is ∼2 mm in width by 4 mm in length. To form the attached co-delivery device, the 2 compartments, each containing either timolol or brimonidine, were stacked together and heat sealed along one edge (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of 2-compartment device fabrication (A). To make each compartment, spun-cast PCL thin films were heat sealed along the edges (I), shown as dotted lines, and filled with either timolol maleate (orange) or brimonidine tartrate (green) (II). The drug-loaded compartments were sealed closed (III) and the 2 compartments were attached at a sealed edge (IV). Each compartment is about 2 mm in width by 4 mm in length. The attached device is shown with grains of rice for scale (B). PCL, polycaprolactone. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jop

In vitro drug release

The release rate of each drug-containing compartment was tested individually. The compartment was submerged in 0.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C on an orbital shaker. Elution medium was replaced with fresh PBS at each time point. Drug concentration was quantified by UV-Vis spectrometry (absorption wavelengths of timolol = 294 nm and brimonidine = 254 nm). The release rate was calculated by dividing the amount of drug released at each time point by the time passed since the previous time point.

To verify that the process of attaching the drug compartments did not lead to defects in the device, drug release rate of the attached compartments was also tested as described above. Drug concentrations were measured using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to separate each drug from the mixed drug solution.

In vivo device implantation

Co-delivery devices were washed with 70% ethanol for 10 s in a sterile hood and subsequently dried in ambient conditions. Implantation of PCL devices in the eyes of adult male and female New Zealand rabbits was approved by the institutional review board and was performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Using ophthalmic microsurgical techniques under sterile conditions in anesthetized rabbits, the devices were implanted in normotensive rabbit eyes as previously described16,17 with minor adjustments. A clear corneal incision was performed using a 2.4 or 2.6 mm slit knife (Alcon Laboratories, Ft. Worth, TX) through which the device was implanted into the anterior chamber of the left eyes. An 8–0 nylon suture (Alcon Laboratories) was used to close the incision.

Sixteen rabbits underwent surgery: 4 rabbits with drug-loaded devices at 3 time points (euthanized after 4, 8, and 13 weeks for analysis) and 4 rabbits with empty devices at the final 13-week time point. Contralateral eyes were untreated and served as controls. Photos were taken after implantation as well as before euthanasia with the Canon camera body and an SLR camera-microscope adapter (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA). Postprocedure, 1% prednisolone (Sandoz, Holzkirchen, Germany) was administered to all rabbits twice a day for 5 days and once a day for 5 additional days to minimize postsurgical inflammation. IOP was measured weekly using a handheld tonometer (TonoVet®; Icare, Vantaa, Finland). All IOP measurements were performed between 12 and 6 pm to control for high diurnal IOP fluctuations. The area under the curve (AUC) of baseline-subtracted IOP values was calculated using the trapezoidal rule over 13 weeks. The AUC of drug-loaded device-treated eyes was compared to the AUC of untreated contralateral eyes and empty device-treated eyes using a 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test to evaluate statistically significant differences among the AUC of the 3 groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Pharmacokinetic analysis in rabbit ocular tissue

At each endpoint, rabbits were anesthetized and 1 mL of venous blood was collected in lithium-heparin tubes (BD Vacutainer®; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and kept on ice until centrifugation. Whole blood was centrifuged at 1300g for 15 min in a refrigerated centrifuge to remove red blood cells from the sample. Before euthanasia, aqueous humor was withdrawn by limbal paracentesis using a 30-gauge needle on a 1 mL syringe. The rabbits were then euthanized by injecting 2 mmol/kg potassium chloride into the marginal ear vein. The ocular globe was enucleated immediately after euthanasia. Cornea, iris-ciliary body (ICB), vitreous, and retina/choroid were dissected, placed in microcentrifuge tubes, and frozen at −80°C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

Cornea, ICB and retina/choroid were extracted in a bullet blender (Next Advance, Troy, NY) at 4°C. For plasma, aqueous humor, and vitreous samples, 25 μL of 50% methanol and 150 μL of acetonitrile/methanol were added to the samples and vortexed vigorously. Spiked standards were prepared using the appropriate blank tissue for each sample. Brimonidine and timolol were dissolved in DMSO, mixed, and further diluted in 50% methanol to prepare spiking solutions. The internal standard mix (brimonidine-d4 and timolol-d5) was prepared in the same way. All samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and 75 μL of supernatant was diluted with 150 μL water +0.1% formic acid.

The LC-MS/MS system consists of a Shimadzu LC-20AB HPLC system interfaced with QTRAP 4000 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Redwood City, CA). LC separation was carried out on an Agilent ZORBAX SB-Phenyl column (50 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 μm) with the following mobile phase: A, LCMS grade water +0.1% formic acid; and B, LCMS grade acetonitrile +0.1% of formic acid. The flow rate was set at 0.6 mL/min. Column temperature was 25°C. The injection volume was 20 μL. Data acquisition and analyses were performed using the Analyst 1.6.1 software (AB SCIEX).

Histological analysis

For histologic studies, the empty device-implanted eyes and contralateral control eyes were enucleated immediately after euthanasia and submerged in 50–60 mL of Hartman's Fixative, and incubated for 1 day. The eyes were then transferred to 70% ethanol until histological analysis. Histological preparation was performed by the Gladstone Histology and Light Microscopy Core (San Francisco, CA). Eyes were hemisected in the sagittal plane. Each half was paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Results

In vitro drug release

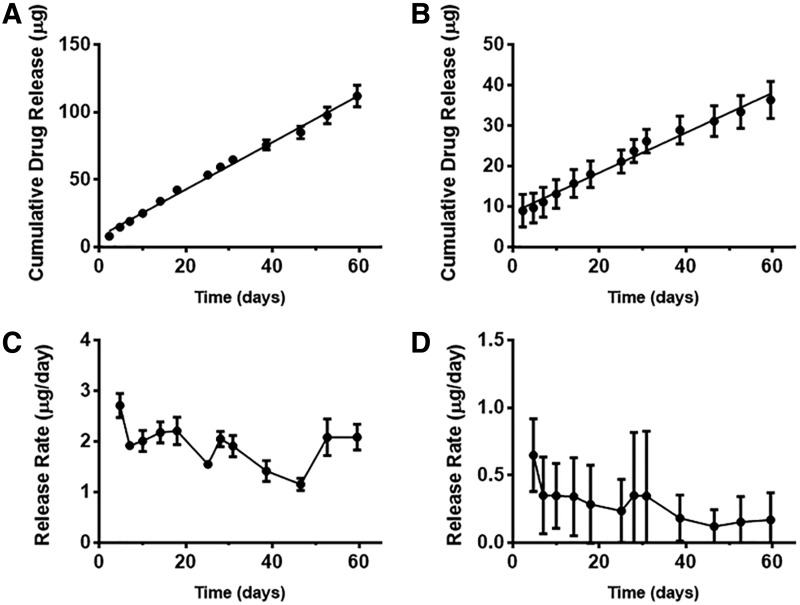

The average in vitro release rate of drug from the device was determined by linear regression on the cumulative drug released versus time curve. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. In vitro drug release results in Fig. 2 show that timolol was released at a rate of 1.75 ± 0.15 μg/day (n = 3, linear regression, R2 = 0.99) and brimonidine was released at a rate of 0.48 ± 0.03 μg/day (n = 3, linear regression, R2 = 0.98), and demonstrate zero-order release kinetics from each drug compartment. The drug released before the first time point is likely due to excess drug powder adsorbed to the outside of the devices during fabrication. Attached compartments led to a measured drug release of 1.57 ± 0.55 and 0.27 ± 0.17 μg/day (n = 3), respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jop). The difference in brimonidine release rate in a single-drug compartment (Fig. 2) compared to the released rate as part of attached devices (Supplementary Fig. S1) can be partly due to variations in device surface areas during fabrication. Since the devices are small and handmade, a slight variation of 0.25 mm in length and width can result in ∼18%–20% difference in device surface area. The variations in release rate may also be attributed to the differences in measurement method (UV-vis and LC-MS/MS, respectively). However, the release rates of attached devices and single compartments were on the same order of magnitude and both demonstrated a zero-order release profile.

FIG. 2.

Cumulative drug release (A, B) and release rates (C, D) of timolol maleate (A, C) and brimonidine tartrate (B, D). Linear regression fit of cumulative drug release versus time demonstrated zero-order release for both timolol and brimonidine. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 for A, C, n ≥ 3 for B, D).

In vivo ocular concentrations

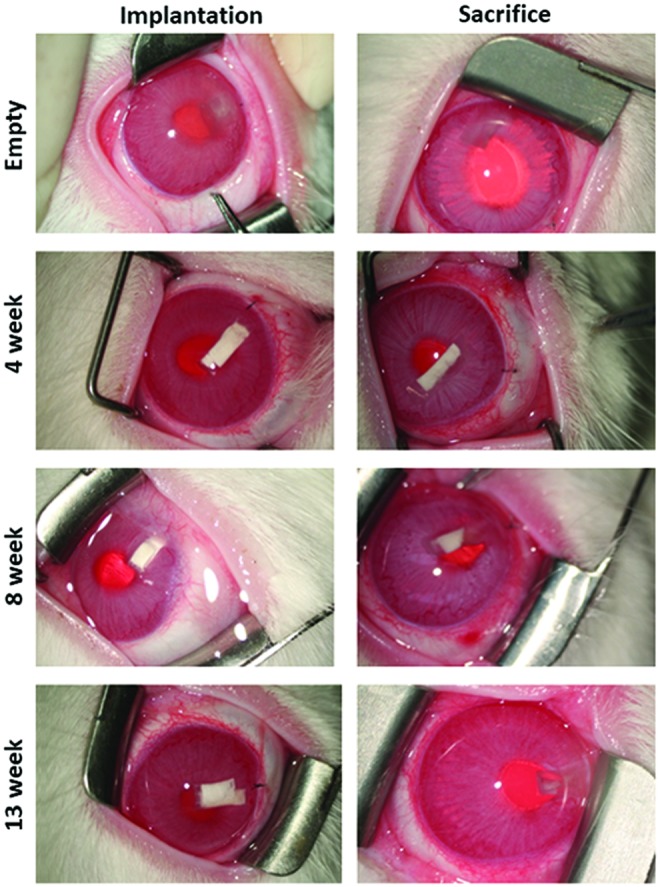

Polymer co-delivery devices were successfully implanted and tolerated in the anterior chamber of rabbit eyes (Fig. 3). No signs of cataracts or ocular inflammation were observed in our study. However, some complications occurred due to the surgical procedure and device shape, as well as other unrelated medical issues. Two 8-week rabbits with drug-loaded devices experienced hyphema during the study period. The rabbits were prescribed 1% prednisolone twice a day for 3–5 days after which the condition was relieved. Three cases of anterior synechia were observed in two 13-week rabbits and one 8-week rabbit. Four cases of corneal neovascularization were observed in two 13-week rabbits and two 8-week rabbits, including 1 case of corneal edema. One 8-week drug-loaded device rabbit had very low IOP caused by the device not being fully enclosed in the anterior chamber. The rabbit was sacrificed early as the surgery was incomplete and the data were not used for analysis. An additional 8-week rabbit was added to the study.

FIG. 3.

Representative photos of rabbit eyes immediately after implantation (left column) and before sacrifice (right column) of empty or drug-loaded co-delivery devices in the anterior chamber of the OS eyes. OS, oculus sinister. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jop

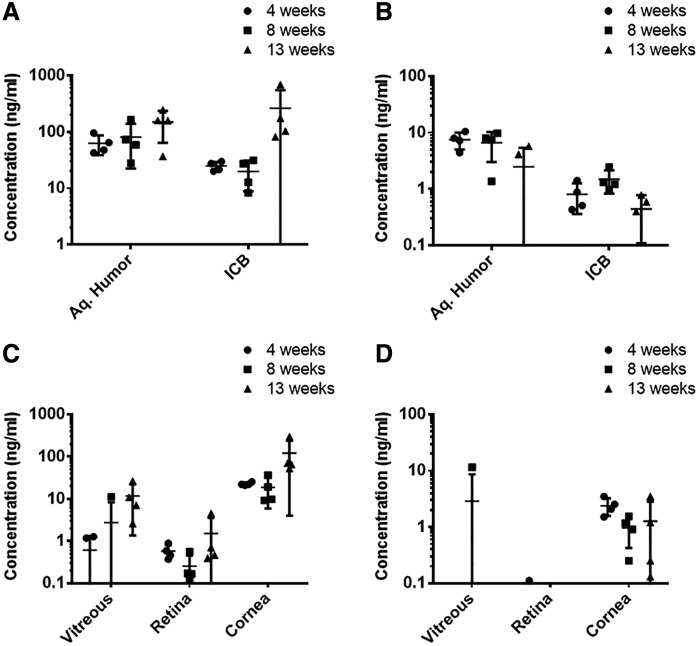

LC-MS/MS analysis of ocular tissues of eyes collected at different time points (week 4, 8, and 13) indicated sustained release of both drugs in the anterior chamber over 13 weeks. Timolol maintained a relatively steady concentration of 98.1 ± 68.3 ng/mL in the aqueous humor (Fig. 4A) with no statistically significant difference in measured concentrations at the 3 time points (P = 0.16). Timolol concentrations in the ICB also indicated sustained release (Fig. 4A). One of the 13-week rabbits showed an ICB concentration more than 6 times that of the 3 other rabbits, which resulted in a large standard deviation in the 13-week group.

FIG. 4.

Concentrations of timolol maleate (A) and brimonidine tartrate (B) in relevant ocular tissues after 4, 8, and 13 weeks of device implantation and concentrations in the aqueous humor (C) and the ICB (D) of both drugs. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ICB, iris-ciliary body.

The average measured aqueous humor concentration for brimonidine was 5.5 ± 3.6 ng/mL. There was no significant difference in average aqueous humor concentrations measured at different time points (P = 0.1). However, two of the four 13-week rabbits had nondetectable brimonidine concentrations in the aqueous humor (Fig. 4B). Brimonidine ICB concentrations were low at all time points with an average of 0.9 ± 0.5 ng/mL. Retina/choroid concentrations were below or close to the quantification limit for both drugs (Fig. 4C, D). In addition, concentrations of both drugs in the plasma were below the limit of detection, indicating that systemic levels of both drugs are very low. The aqueous humor concentrations in the untreated contralateral eyes were below quantification limit, indicating no crossover effect.

Intraocular pressure

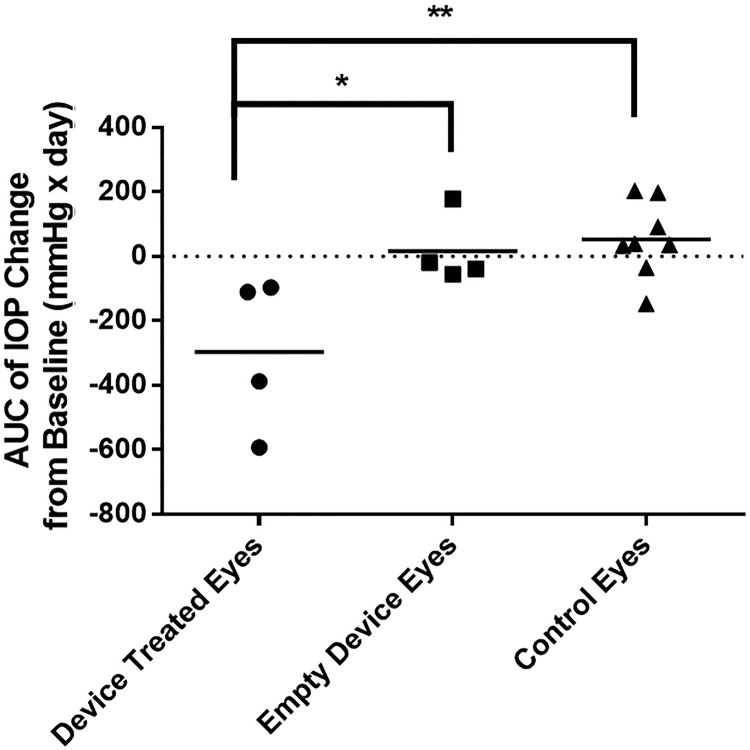

IOP measurements of the device-implanted eyes were compared to those of untreated, contralateral eyes for ∼13 weeks after device implantation (Fig. 5). Presurgery baseline IOP of device-implanted and contralateral eyes was 11 ± 2.1 and 9.4 ± 1.8 mmHg, respectively. Within 7 days, the IOP of the drug-loaded device-treated eyes dropped by 4.4 ± 2.9 mmHg, while the IOP for the untreated contralateral eyes increased by 1.3 ± 2.3 mmHg. This corresponds to an average relative drop of 37% (normalized to each rabbit's baseline IOP). Over 13 weeks, the IOP of the drug-loaded device eyes decreased by 3.4 ± 1.6 mmHg on average, whereas the IOP of the control eyes increased on average by 0.54 ± 0.97 mmHg. Cumulative IOP reduction was evaluated by comparing the AUC of baseline-subtracted IOP measurements of the 3 groups (Fig. 6). The drug-loaded device-treated eyes resulted in a statistically significant cumulative reduction in IOP compared to untreated contralateral eyes (ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, P < 0.01) and empty device-treated eyes (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in cumulative IOP reduction between empty device-treated eyes and untreated contralateral eyes.

FIG. 5.

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 4) of IOP change from baseline for drug-loaded eyes (A) and empty device eyes (B) compared to their contralateral control eyes over 91 days. IOP, intraocular pressure. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jop

FIG. 6.

Cumulative IOP reduction represented as the AUC of baseline-subtracted IOP values of drug-loaded device-treated eyes (n = 4), empty device-treated eyes (n = 4), and their contralateral control eyes (n = 8) over 91 days. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01) Mean ± standard deviation. AUC, area under the curve.

Histological analysis after 13 weeks of device implantation

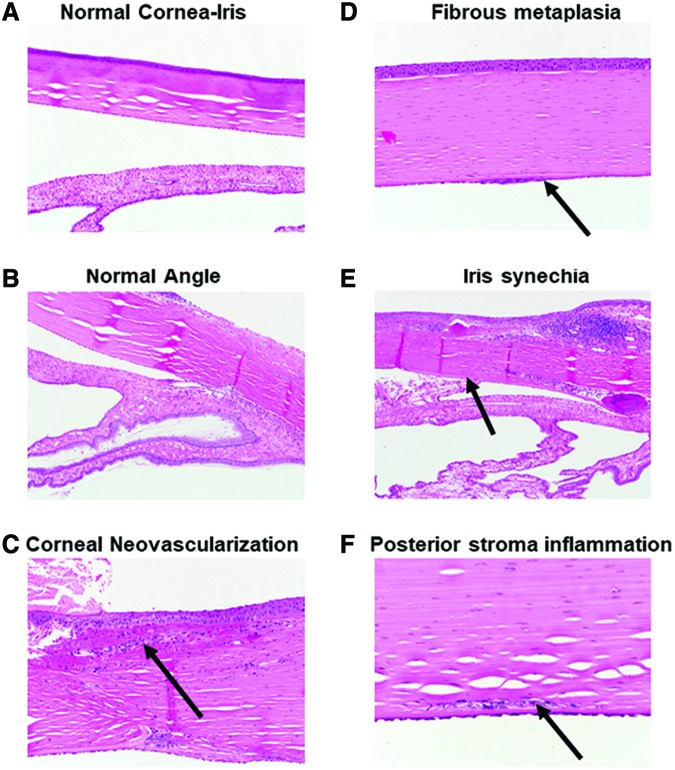

Granulation tissue with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate was present at the site of incision in the cornea, consistent with a surgical wound. In 2 cases, there was corneal neovascularization associated with the wound (Fig. 7C). At the site of device implantation, there is evidence of local mechanical disruption to the anterior iris and posterior cornea. There were 2 cases of anterior synechia (Fig. 7E) and 3 cases of fibrous metaplasia due to the device touching the iris and corneal endothelium (Fig. 7D). There was 1 case of iris neovascularization. The disruptions and some inflammation are seen at the implantation site (Fig. 7F), and no effect on the tissue is observed in the distal half of the eye (Fig. 7A, B). No global inflammatory response was observed, which agrees with previous studies using PCL devices in the eye.17

FIG. 7.

Histological images of the rabbit normal cornea (A) and normal angle (B) in the anterior segment of the OS eye. Images of the anterior segment showing examples of corneal neovascularization (C), fibrous metaplasia shown by thickening of the endothelium (D), iris synechia (E), and lymphocytes in the posterior stroma signaling focal inflammation (F). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jop

Discussion

Poor patient compliance is a well-documented problem with topical glaucoma therapies. Sustained delivery formulations of glaucoma medication represent an unmet need in the field, particularly the simultaneous delivery of multiple hypotensive agents. In this study, we report the development of a polymeric intracameral ocular implant for simultaneous sustained delivery of both timolol maleate and brimonidine tartrate.

According to pharmacokinetics analysis, the amount of drug in the contralateral eye and the plasma is below quantifiable limits of LC-MS/MS (<1 ng/mL). This allows our device to avoid systemic effects associated with topical beta blocker application, which can be seen rarely with topical eyedrops.19 Assuming a simple 1-compartment model with a fixed release source and 1 route of elimination, the steady-state concentration  of each drug can be estimated from the half-life of each drug using the following 2 equations:

of each drug can be estimated from the half-life of each drug using the following 2 equations:

|

where  is the elimination rate constant,

is the elimination rate constant,  is the release rate from the device,

is the release rate from the device,  is the half-life of each drug in the aqueous humor, and V is the volume of the aqueous humor assuming the drug is distributed across the entire volume. The steady-state concentration of timolol concentration in the aqueous humor was calculated to be 323.8 ng/mL based on its half-life of 60 min20 and assuming a fixed release source at the measured in vitro release rate of 1.75 μg/mL and an aqueous humor volume of 0.325 mL.21 Our measured aqueous humor concentration is on the same order of magnitude, but is ∼3-fold lower, suggesting that the in vivo release rate of timolol from the device might be slightly slower than in vitro. However, this concentration is consistent with the aqueous humor concentration measured after 18 h of administering a single dose of topical 0.5% timolol to human patients, which was reported to be 105.5 ± 60.9 ng/mL.22 Based on a study of beta receptor binding activity of timolol in the aqueous humor, the measured timolol concentration of ∼100 ng/mL in the aqueous humor would result in 99% beta1 receptor occupancy.22

is the half-life of each drug in the aqueous humor, and V is the volume of the aqueous humor assuming the drug is distributed across the entire volume. The steady-state concentration of timolol concentration in the aqueous humor was calculated to be 323.8 ng/mL based on its half-life of 60 min20 and assuming a fixed release source at the measured in vitro release rate of 1.75 μg/mL and an aqueous humor volume of 0.325 mL.21 Our measured aqueous humor concentration is on the same order of magnitude, but is ∼3-fold lower, suggesting that the in vivo release rate of timolol from the device might be slightly slower than in vitro. However, this concentration is consistent with the aqueous humor concentration measured after 18 h of administering a single dose of topical 0.5% timolol to human patients, which was reported to be 105.5 ± 60.9 ng/mL.22 Based on a study of beta receptor binding activity of timolol in the aqueous humor, the measured timolol concentration of ∼100 ng/mL in the aqueous humor would result in 99% beta1 receptor occupancy.22

Based on the half-life of brimonidine in the aqueous humor of 34 min,23 and the in vitro release rate of 0.48 μg/day, the expected in vivo steady-state concentration in the aqueous humor is 50.2 ng/mL. The measured concentrations in the aqueous humor and ICB are an order of magnitude lower than anticipated based on the in vitro release rate. Upon examining the devices at week 13, we noticed that little to no brimonidine powder was visible in the devices. Based on the amount loaded (∼1 mg) and their release rate preimplantation, we anticipated the drug release from the devices to last for a substantially longer period of time. This suggests that (1) the in vivo release rate of brimonidine may be higher than the measured rate in vitro, leading to faster depletion of the device reservoir, and (2) there are modes of clearance in addition to the outflow of aqueous humor, such as degradation, which might be contributing to the low tissue concentrations.

The return to baseline IOP toward the end of the study may be due to the lower brimonidine concentrations in the target tissues measured at week 13 compared to weeks 4 and 8. For example, the brimonidine aqueous humor concentration decreased to 33% at week 13 compared to week 4, whereas the ICB concentration decreased to 55%. However, even with the low brimonidine concentrations (under 10 ng/mL) in the aqueous humor and ICB, the devices were able to achieve statistically significant cumulative IOP reductions at earlier time points. There was a maximum IOP drop of 5.5 ± 2.8 mmHg on day 14, which corresponds to a 47% reduction from baseline. According to the FDA approval letter,23 brimonidine tartrate ophthalmic solution 0.1% resulted in a maximum of 29% reduction in IOP after 3 h in male albino New Zealand rabbits. It is important to note that there is less room for IOP reduction in normotensive rabbits compared to rabbit models of elevated IOP.

The histological analysis shows that there was no global inflammation in the eye. All abnormalities observed are local to the device implantation site. Given the small dimensions of the rabbit eye relative to the human eye (25% relative volume)24 the device size was associated with iris and corneal contact in the confines of the small anterior chamber. However, the current device geometry can be redesigned to further improve biocompatibility. One aspect of the geometry was the 2-armed, V-shaped design. We observed that the 2 arms of the device did not remain folded, and instead opened up within the eye into a wider V-shape, pushing against the corneal epithelium and the iris. This created mechanical pressure that explains the observed damage in those tissues. Future goals include reconfiguring and further miniaturizing the co-delivery devices to further improve biocompatibility.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that these polymer thin-film intracameral implant devices can achieve controlled release of 2 different hypotensive agents at different release rates. The device achieved a statistically significant reduction of cumulative IOP over 13 weeks in normotensive rabbits. Timolol maleate concentration in the target tissue was maintained for 13 weeks. While the in vivo release rate of brimonidine was lower than expected, the low concentrations still achieved significant IOP drop. Further optimization of brimonidine formulation and/or device size can increase the in vivo release rate and duration of brimonidine through the thin-film device. This study demonstrates that the prototype device has the potential to achieve sustained release of 2 hypotensive agents for glaucoma therapy. The PCL thin-film co-delivery device can also be tuned for the sustained, zero-order release of other hypotensive agents. PCL is a lipophilic polymer, which facilitates the transport of lipophilic drugs such as prostaglandin analogs and ROCK inhibitors such as netarsudil.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by That Man May See Foundation, NIH-NEI EY002162—Core Grant for Vision Research, Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01EY021574.

Author Disclosure Statement

T.A.D. is a co-founder of Zordera and is on the advisory board for Santen; R.B.B. receives a research grant from Genentech, receives consulting fees from Ribomic, Inc. and AntriaBio, is a co-founder of Zordera, is on the advisory board for Santen, and is on the advisory board for Sandoz, Biotime, and Quark. The remaining authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Tham Y.C., Li X., Wong T.Y., Quigley H.A., Aung T., and Cheng C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 121:2081–2090, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim C.Y., Park K.H., Ahn J., et al. Treatment patterns and medication adherence of patients with glaucoma in South Korea. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101:801–807, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frech S., Kreft D., Guthoff R.F., and Doblhammer G. Pharmacoepidemiological assessment of adherence and influencing co-factors among primary open-angle glaucoma patients—an observational cohort study. 1–14, 2018. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Naito T., Namiguchi K., Yoshikawa K., et al. Factors affecting eye drop instillation in glaucoma patients with visual field defect. PLoS One. 12:1–11, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olthoff C.M.G., Schouten J.S.A.G., Van De Borne B.W., and Webers C.A.B. Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension: an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 112:953–961, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reardon G., Schwartz G.F., and Mozaffari E. Patient persistency with topical ocular hypotensive therapy in a managed care population. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 137(1 Suppl.), 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gatwood J.D., Johnson J., and Jerkins B. Comparisons of self-reported glaucoma medication adherence with a new wireless device: a pilot study. J. Glaucoma. 26:1056–1061, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lavik E., Kuehn M.H., Shoffstall A.J., Atkins K., Dumitrescu A.V., and Kwon Y.H. Sustained delivery of timolol maleate for over 90 days by subconjunctival injection. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 32:642–649, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fedorchak M.V., Conner I.P., Medina C.A., Wingard J.B., Schuman J.S., and Little S.R. 28-day intraocular pressure reduction with a single dose of brimonidine tartrate-loaded microspheres. Exp. Eye Res. 125:210–216, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pek Y.S., Wu H., Mohamed S.T., and Ying J.Y. Long-term subconjunctival delivery of brimonidine tartrate for glaucoma treatment using a microspheres/carrier system. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5:2823–2831, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maiti S., Paul S., Mondol R., Ray S., and Sa B. Nanovesicular formulation of brimonidine tartrate for the management of glaucoma: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 12:755–763, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mealy J.E., Fedorchak M.V., and Little S.R. In vitro characterization of a controlled-release ocular insert for delivery of brimonidine tartrate. Acta Biomater. 10:87–93. 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peng C.C., Burke M.T., Carbia B.E., Plummer C., and Chauhan A. Extended drug delivery by contact lenses for glaucoma therapy. J. Control. Release. 162:152–158, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fu J., Sun F., Liu W., et al. Subconjunctival delivery of dorzolamide-loaded poly(ether-anhydride) microparticles produces sustained lowering of intraocular pressure in rabbits. Mol. Pharm. 13:2987–2995, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pitha I., Kimball E.C., Oglesby E.N., et al. Sustained dorzolamide release prevents axonal and retinal ganglion cell loss in a rat model of IOP-Glaucoma. 7:1–12, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J., Kudisch M., da Silva N.R.K., et al. Long-term intraocular pressure reduction with intracameral polycaprolactone glaucoma devices that deliver a novel anti-glaucoma agent. J. Control. Release. 269:45–51, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J., Kudisch M., Mudumba S., et al. Biocompatibility and pharmacokinetic analysis of an intracameral polycaprolactone drug delivery implant for glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57:4341–4346, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lance K.D., Good S.D., Mendes T.S., et al. In vitro and in vivo sustained zero-order delivery of Rapamycin (sirolimus) from a biodegradable intraocular device. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56:7331–7337, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mäenpää J., and Pelkonen O. Cardiac safety of ophthalmic timolol. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 15:1549–1561, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Acheampong A.A., Breau A., Shackleton M., Luo W., Lam S., and Tang-Liu D.D. Comparison of concentration-time profiles of levobunolol and timolol in anterior and posterior ocular tissues of albino rabbits. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 11:489–502, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Missel P.J. Simulating intravitreal injections in anatomically accurate models for rabbit, monkey, and human eyes. Pharm. Res. 29:3251–3272, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saari K.M., Ali-Melkkilä T., Vuori M-L, Kaila T., and Lisalo E. Absorption of ocular timolol: drug concentrations and β-receptor binding activity in the aqueous humour of the treated and contralateral eye. Acta Ophthalmol. 71:671–676, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2004. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/021770s000_PharmR.pdf Accessed December19, 2018

- 24. Bozkir G., Bozkir M., Dogan H., Aycan K., and Güler B. Measurements of axial length and radius of corneal curvature in the rabbit eye. Acta Med. Okayama. 51:9–11, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.