Summary

In recent years, strong evidence has emerged suggesting that insufficient duration, quality, and/or timing of sleep are associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), and various mechanisms for this association have been proposed. Such associations may be related to endophenotypic features of the sleep homeostat and the circadian oscillator, or may be state-like effects of the environment. Here, we review recent literature on sleep, circadian rhythms and CVD with a specific emphasis on differences between racial/ethnic groups. We discuss the reported differences, mainly between individuals of European and African descent, in parameters related to sleep (architecture, duration, quality) and circadian rhythms (period length and phase shifting). We further review racial/ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors, and develop the hypothesis that racial/ethnic health disparities may, to a greater or smaller degree, relate to differences in parameters related to sleep and circadian rhythms. When humans left Africa some 100,000 years ago, some genetic differences between different races/ethnicities were acquired. These genetic differences have been proposed as a possible predictor of CVD disparities, but concomitant differences in culture and lifestyle between different groups may equally explain CVD disparities. We discuss the evidence for genetic and environmental causes of these differences in sleep and circadian rhythms, and their usefulness as health intervention targets.

Keywords: Admixture, Health disparities, Cardiovascular disease, Circadian rhythm, Sleep

Introduction

Anatomically modern humans first emerged from Africa at least 70,000 years ago, and began to colonise the other continents. There are reasons to hypothesise that differences in parameters related to circadian rhythms and sleep evolved as groups of humans gradually moved away from the equatorial zone in the direction of the poles and settled there [1], just as the different light conditions favoured a loss of skin pigmentation. Indeed, polymorphisms in specific genes have been reported to associate with photoperiod, and signatures of positive selection detected [2]. After millennia of gradual expansion, our species has experienced some profound rapid changes during the last few centuries [3]. Voluntary and forced migration has moved individuals and groups from the environments to which their ancestors had adapted over generations into different environments and living conditions, and where previously separate populations are now undergoing an unprecedented and accelerating degree of admixture.

The last few centuries have also been characterised by the gradual transition from an agrarian to an industrial society, which has afforded unprecedented benefits as well as novel challenges to human health. This transition, where the major causes of death have shifted from nutritional deficiency and infectious disease to degenerative chronic disease — cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and cancer — has been named “the epidemiologic transition” [3]. This transition is still ongoing in many countries and regions. An important contributor to this increase in chronic diseases is change in diet. Our behavioural drives evolved to maximise intake of precious energy-rich nutrients whenever available, but today, many of us have almost unrestricted access to high-calorie foods.

Parallel to the epidemiologic transition, affordable electricity has emerged, which first enabled us to keep our homes lit regardless of the external photoperiod, and then provided us with endless options for work and distractions at any hour of the night and the day. This has long been considered to have caused a decrease in the length and a shift in the timing of sleep. A recent study of hunter-gatherer societies [4] showed less total sleep in a community that had recently been connected to the electrical grid than in a community that had not. And whilst there is no reliable evidence suggesting a decrease in average sleep time during recent decades, there is stronger evidence that the proportion of short sleepers has increased [5] and that there has been a significant decrease in sleep amongst adolescents [6,7]. It can also be hypothesised that the intensive forced mass migration of Africans to Northern and (even more prominently) Southern latitudes of the Americas [8] may, in addition to the social inequalities rooted in the aftermath of slavery, also convey physiological maladaptations to high-amplitude photoperiods that need to be understood in order to be mitigated [1]. The situation is further complicated by socioeconomic stratification of racial/ethnic groups within societies, making it complex to disentangle to which extent observed differences are caused by genetic traits or states associated with environmental variables.

In public health terms, the most dramatic fallout of the epidemiological transition has been an increase in CVD, which is now the main cause of disability and death in the modernised world. The global cost of CVD is around US$900 billion, and, as the world population ages, this figure is set to rise to over US$1,000 billion by 2030 [9]. CVDs include a number of diseases of the heart and circulation such as coronary heart disease and stroke, alongside hypertensive, inflammatory, and rheumatic heart disease. A fundamental need to understand the root causes of CVD prevalence remains, and much of our knowledge about prevention is owed to the pioneering Framingham study [10]. This longitudinal cohort study identified a number of potentially modifiable risk factors — high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, hypertension, diabetes, high adiposity, obesity, smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity. Although the vast majority of the Framingham cohort consists of middle class individuals of European descent, the main findings of the study have been confirmed, and gained universal acceptance [11]. Although treatment for CVD has also improved considerably over the last decades; CVD remains a major cause of morbidity, and the well-known principle that prevention is better than cure holds true for CVD, particularly as the accessibility of pharmacological or surgical interventions is neither universal nor without risk. Nonetheless, current modifiable risk factors for CVD, such as diet and physical activity, are notoriously difficult to change. Therefore, there is a pressing public health need to understand whether other potentially modifiable targets may also reduce CVD risk, particularly among groups disproportionately burdened by disease. Here, we discuss the case for sleep and circadian rhythms as modifiable targets. This discussion probably defines at least as many gaps in current knowledge (summarised in the Research Agenda) as it fills. The aim of this review is not only to identify the differences between different groups of people which could potentially be attributed to genetically determined physiological differences, but also to convey an appreciation of the many non-genetic factors, such as environment or culture, that could potentially explain the same observations wholly or in part. Either way, it is intended that the review will help make the case for additional research that includes novel population groups and methodologies.

Circadian rhythms and sleep and their importance to human health

Endogenously generated through transcriptional and post-transcriptional networks of specific clock genes, circadian rhythms enable organisms to actively anticipate, as opposed to passively react to, the predictable changes that occur across the 24-hour day:night cycle. In real-life conditions, circadian rhythms are continuously entrained by external signals, known as Zeitgebers, most prominently by light. Circadian rhythms are of fundamental importance to human health. Prominent effects on the body include an impact on sleep-wake cycles, hormone release, body temperature, and metabolism. Continuous entrainment of the circadian clock is required not only because of the variability in photoperiod in non-equatorial regions, but also because the internal period length of the oscillator is not exactly the combined length of a day and a night. In humans, it shows a normal distribution around an average of 24.2 h [12]. Modern life, however, does not replicate the daily patterns of our ancestors, around which the entrainment mechanisms of Zeitgebers evolved. We spend often considerable amounts of time indoors, and many of us work shifts with nocturnal and/or irregular hours. Thus, our 24/7 society induces a high prevalence of social jetlag, a discrepancy between endogenous circadian clocks and socially imposed external ones [13].

The circadian phase of physical inactivity is augmented by sleep, a specialised programme of reversible uncoupling from external stimuli involving different stages defined by specific electrophysiological signatures. Sleep is closely linked to circadian rhythms. In addition to its profound and obvious behavioural manifestations, sleep and its transition into and out of wakefulness also have manifestations on the molecular and physiological level that are independent of the effects of circadian rhythms on both metabolic and endocrine function [14].

The relationship between circadian rhythms, sleep and cardiovascular disease

Circadian rhythm and cardiovascular health

Circadian rhythms have been associated with CVD and its risk factors, including diabetes (which is outside of the scope of this review) and obesity, on multiple levels. Cardiomyocyte metabolism is under circadian control [15], and circadian and diurnal rhythms are, in turn, observed in blood pressure, heart rate, and platelet aggregability, as well as in the incidence of multiple categories of CVD [16]. This has inspired multiple lines of investigation of the relationship between circadian disruption and cardiovascular risk factors and health outcomes.

A glimpse of the effects of circadian maladaption on CVD can be gained from studies of shift work, which is associated with both circadian disruption and sleep loss. Prevalence estimates of just under 20% have been reported for shift work in the industrialised world [17]. Although the general label “shift work” encompasses a multitude of different schedules, which vary in their degrees of circadian maladaption, sleep deprivation, and other confounding factors, many studies have observed that shift work is associated with impairments in health. Observational evidence has demonstrated that shift work is associated with an overall increased risk of death, prominently by causes related to CVD. For example, the Nurses’ Health Study examined the relationship between night shift work and all-cause or CVD mortality. Six or more years of rotating night shift work was associated with an 11% increase in risk of all-cause mortality, whereas the risk of CVD mortality was increased by 19% for 6 to 14 years rotating night shift work and 23% for 15 or more years [18]. In parallel to these findings, shift work is also associated with several cardiometabolic diseases and their risk factors. These have recently been reviewed elsewhere [18].

Experimental studies have also made important contributions to our understanding of the effects of circadian disruption on cardiovascular risk factors. A key report was based on a 10-day experiment where 10 participants underwent a forced desynchronisation protocol with a 28-hour day-night cycle. Circadian disruption was associated with a significant increase in leptin, insulin, and glucose, a reversal of the daily cortisol rhythm, and an increase of 3 mm Hg in mean arterial pressure during the hours of wakefulness [21]. Other forced desynchrony experiments have identified that circadian misalignment reduces the thermal effect of feeding energy expenditure and total daily expenditure [22], resting metabolic rate [19], as well as a six-fold reduction of rhythmic transcripts in the human blood transcriptome [23].

Modest shifts in circadian phase have also been found to have cardiometabolic effects and increase overall risk profile. The one-hour shift associated with the onset of daylight savings (summer) time has been associated with a 6—10% increase in myocardial infarction rates [24]. Adolescents and adults with delayed chronotypes have had poorer dietary habits [25] and higher measures of adiposity [25][26]. Evening chronotypes are also associated with an increased risk of metabolic disorders [26].

The timing of meals has been previously shown to predict the effectiveness of weight loss [27], and later sleep timing has been associated with social jetlag [13]. The health effects of social jetlag are widespread and include numerous risk factors for CVD events such as reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein, higher cholesterol levels, higher triglycerides, higher fasting plasma insulin, insulin resistance [28] and obesity [29].

Sleep duration and quality, and cardiovascular health: Observational studies

The evidence for a relationship between insufficient sleep and CVD is well established [30]. Prospective epidemiologic studies have found that shorter sleep duration is associated with incident hypertension and incident coronary artery calcification, a predictor of the development of coronary heart disease. For example, the US-based Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study identified a link between short sleep duration and hypertension with 37% higher odds of incident hypertension per hour decrease in average nightly sleep [31]. The Nurses’ Health Study [32] found a significantly increased risk of incident coronary heart disease over 10 years associated with short (≤5 h/night) and long (≥9 h/night) self-reported sleep duration. Such results are typical of the field; a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort studies (almost 475,000 adults) found that compared to 7—8 hours sleep, short and long sleep duration was associated with increased risks of coronary heart disease and stroke [33].

The most common sleep disorders are obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and insomnia, each of which affects some 15% of the population. Although more prevalent in the obese, OSA has negative effects on cardiovascular health outcomes (increased cardiovascular disease risk, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, stroke and cardiovascular mortality) that are additive to those caused by obesity alone. The relationship between OSA and CVD has been reviewed elsewhere [34] and falls outside of the scope of this review. Laboratory studies reviewed here excluded people with OSA wherever possible. Insomnia is characterised by chronic difficulties in initiating or maintaining sleep, and may thus affect both the quantity and the quality of sleep. Insomnia has been repeatedly associated with increased cardiovascular risk [35]. These trends were further confirmed in a recent population-based study, finding that over the course of 11 years, individuals with insomnia were three times more likely to develop heart failure compared to those without insomnia symptoms [36].

Epidemiological evidence for an association between CVD and poor sleep quality has also emerged. A 12-year follow up study of over 1,900 middle-aged individuals in Sweden found that sleep complaints predicted coronary artery disease mortality in males [37]. Low sleep efficiency has also been associated with a blunted nocturnal dip in systolic blood pressure, a risk factor for CVD, in normotensive adults [38]. While sleep duration and sleep quality may share underlying mechanisms, cross-sectional evidence has indicated that these two sleep characteristics do not necessarily overlap. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) study of over 30,000 participants attempted to understand whether cardiometabolic outcomes were more related to sleep duration or perceived sleep insufficiency. Taken in isolation, subjective sleep insufficiency was associated with BMI, obesity and hypercholesterolaemia, whereas sleep duration was associated with all outcomes tested including BMI, obesity, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, heart attack and stroke. Examining both sleep duration and insufficiency together within the same model identified that both had unique effects on hypertension, and that sleep duration alone accounted for the risk of heart attack and stroke (both short and long sleep duration) BMI and obesity (short sleep duration) [39].

Sleep duration and quality, and cardiovascular health: Experimental studies

Experimental studies that manipulate sleep in a laboratory setting are useful because the conditions can be carefully controlled and measurements are often very reliable and precise (e.g. polysomnography). However, their ability to inform effects on long-term outcomes such as weight gain or development of chronic disease is limited. Nonetheless, such studies can measure cardiovascular function, which allows a degree of extrapolation. For example, a study in mild to moderately hypertensive patients who were randomised within a crossover study design to have acute sleep deprivation during the first part of the night or a full night’s sleep one week apart. During the sleep deprivation day, the mean 24-hour blood pressure and heart rate and levels of urinary adrenaline were higher when they were sleep deprived [40]. These findings have been replicated elsewhere, and atrial baroreflex resetting was identified as the mechanism mediating the effect of sleep deprivation on increased blood presssure [41]. Another experimental study found that sleep debt resulted in reduced glucose tolerance, increased evening cortisol levels and increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system [14]. Experimental studies that impaired sleep quality without reducing total sleep time observed increased cortisol levels and sympathetic nervous system activity [42].

Mechanism for the impact of sleep and circadian rhythms on cardiovascular health

Taken together, the evidence for a relationship between sleep, circadian rhythms and CVD is considerable. Whilst circadian processes are present in all cells of the body, the effects of sleep on the peripheral body will by definition be indirect. Although our understanding is incomplete, many of the proposed mechanisms involve modulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and have been reviewed recently [42]. For activation of the HPA axis, there is strong evidence to suggest that cortisol levels are an important predictor of sleep duration and quality across different ethnic groups in that shorter sleep duration, lower sleep efficiency, and insomnia were associated with changes in the diurnal cortisol levels [45]. Sleep deprivation causes constriction of blood vessels and increased signalling from endothelial cells, and indirectly, through the activation of immune cells, increase in insulin resistance, and adipose tissue signalling, which collectively are predictors of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and obesity [43]. Circadian rhythms have been observed in vivo in the expression of multiple human genes, and perturbation of these expression patterns have been observed both in circadian desynchrony [23] and in partial sleep deprivation [46].

The complex concept of race and ethnicity

The distinction between the definitions of “race” versus “ethnicity” is not clear, varies across and even within countries, and has varied across time. Ethnicity typically takes into account geographical ancestry, skin tone and other physical traits, as well as culture, history, and religion [47], and often has more categories than race. Further, there is considerable ongoing debate as to the degree to which races and ethnicities are social or biological constructs [47,48]. For example, the American Anthropological Association’s statement on race argues that disparities between groups are not biological, but due to social and historical factors [49]. Genetically, the issue of race is very intricate, as there are no known combinations of genes which can define specific biological races, and in reality, there can be more genetic variability within a single race than between different ones [50]. Complicating matters further, within a society, race/ethnicity is difficult to disentangle from socio-economic status and environmental conditions. Throughout this review, we will use the binomial “race/ethnicity”. Further, it is important to note that the broad racial/ethnic categories used in most of the literature, including “black”, “white”, “Hispanic/Latino” and “Asian”, are very heterogeneous groups. People grouped under a single race/ethnicity may differ considerably not only in genetic background, but also in primary language use, country of origin, immigration, cultural practices and socioeconomic backgrounds. Indeed, racial/ethnic categorisation will always be imprecise [51]. Understanding the roots of disparities in health will ultimately require a more nuanced understanding of these differences within as well as between these broad racial/ethnic groups.

None of these issues have made the writing of this review any easier. More often than not, we have referred to published data using the terminology of the authors, so long as the geographical, social, and historical context of the groups described can be inferred by the reader. Where we diverge from the terminology of our sources, this has been introduced in the interest of clarity, or in order to avoid the use of incorrect and archaic verbiage (e.g. “Caucasian”).

Race/Ethnicity and cardiovascular disease

Racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease

There is ample evidence for substantial and persistent disparities between racial/ethnic groups in cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes. Epidemiological evidence has indicated that there are racial/ethnic differences in CVD mortality. For example, in US data from 2010, African-Americans had the highest age-adjusted CVD mortality (224.9/100,000) followed by non-Hispanic Whites (179.9/100,000), Hispanic/Latinos (132.8/100,000) and Americans of East Asian descent (100.9/100,000) [52]. By contrast, in the UK, individuals of Afro-Caribbean ancestry have lower rates of mortality caused by ischaemic heart disease, but higher rates of stroke mortality compared to those of European ancestry [53]. Corroborating evidence for ethnic differences in CVD and associated risk factors has also been established in Canada where mortality rates from ischaemic heart disease were higher in people of European or South Asian descent than in people of Chinese descent [54].

CVD risk factors and race/ethnicity

The main risk factors for CVD, include hypertension, high cholesterol, obesity, diabetes, and smoking, vary by race/ethnicity, which may partly explain disparities in CVD. For example, US-based studies have found prevalence of hypertension to be substantially higher among African-American adults than among European-Americans [55,56]. A study of 457 African-Americans associated objectively measured skin colour with blood pressure —including a finding that darker skinned individuals have higher blood pressure (an increased by 2 mm for every 1 standard deviation increase in skin darkness) [57]. In the UK, most studies have reported higher rates of hypertension among Afro-Caribbean and South Asian groups, but not all studies have seen racial/ethnic differences, which may be due to more recent immigration of the minority groups [58]. Drawing comparative conclusions from different studies performed in different countries is complicated by the fact that ethnic minorities have lived for generations in some countries, but immigrated within the lifetime of the mature individuals in others.

There is evidence that cholesterol levels vary by race/ethnicity, but measures known to indicate elevated risk — high total, high LDL or low HDL — vary between studies. Figures collected for the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009— 2010 found that Hispanic males had a greater prevalence of high total cholesterol compared to whites and blacks (14.8% vs. 11.5% and 8.8%) [59]. This pattern was not true for women where European-Americans were more likely to have high total cholesterol (15.3%) when compared to African-Americans (10.9%) and Latinos (13.7%). For LDL cholesterol, 38.8% of male Latinos had high values compared to 30.7% for African-Americans and 29.4% for European Americans [59]. In women, results were somewhat different, with high LDL cholesterol observed in 33.6% of African-American women, 31.8% of Latinos women and 32.0% of white women. Somewhat surprisingly, multiple population based studies have found that higher HDL levels are more likely to be found in blacks than in whites including studies from the United States, Canada and the UK (Afro-Caribbean vs. white) [60]. Thus taken collectively, the relationship between race/ethnicity and cholesterol is complex, but reported differences have been repeatedly observed.

In the US, the prevalence of obesity (BMI>30) varies by race/ethnicity, especially among women [61]. For example, the prevalence of obesity in Asian-Americans is 4.8%, whereas for African-Americans, it is 34.8% [61]. Sedentary behaviour is also understood to vary by ethnicity, being more common in African-Americans and Hispanic/Latinos compared to European-Americans [59,62]. A study of over 30,000 individuals identified that racial/ethnic minorities were less likely to engage in healthy exercise and dietary behaviours than European-Americans, noting that differences were most pronounced in middle age [63]. Thus, there is growing evidence of ethnic differences in obesity and its risk factors.

In the UK, ethnic minorities are more likely to smoke than the general population, and may be less likely to quit [64]. 37% of Afro-Caribbean men and 36% of Bangladeshi men are estimated to smoke regularly, compared to 27% of white English. Conversely, white women were more likely to smoke compared to women of all other ethnicities. In the US, Hispanics and people of Asian descent are the most likely to smoke (31.2% and 29.1% respectively) compared to whites (16.9%), blacks (18.6%) Native Americans/Alaska Natives (8.6%) and multiracial individuals (12.6%) [65]. Thus, although cigarette smoking is an important risk factor for CVD, the relationship between race/ethnicity and smoking varies by country and by sex [59].

An important environmental factor leading to health disparities is differential socioeconomic status, which is associated with access to resources including healthcare [66]. Higher levels of education are also associated with healthier lifestyles and education is usually lower in disadvantaged racial/ethnic groups [67]. Evidence that CVD disparities may be mainly due to environmental rather than genetic factors comes from studies comparing African-Americans to Africans. For example, the age-associated rise in hypertension was twice as high in African-Americans as in West African populations [68]. Further, it has been suggested, based on a study performed in Brazilians of African descent, that greater cultural consonance, “the degree to which individuals are able to approximate in their own behaviors the prototypes for behavior encoded in shared cultural models”, is protective against hypertension [69]. A study in Puerto Rico reported that for adults with a low socioeconomic status, darker self-reported skin colour was associated with higher blood pressure, while conversely, for adults of high socioeconomic status, darker self-reported skin colour was associated with lower mean blood pressure [70].

As summarized, a growing body of scientific work has identified racial/ethnic differences across an array of CVD events and outcomes that remain after the adjustment for covariates such as age, sex, education and socioeconomic status, and that the difference between blacks and whites in the United States is in fact widening [67]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to disentangle the environmental and genetic influences that drive these disparities, in order to develop ways in which they can be alleviated.

Racial/Ethnic differences in circadian rhythms and sleep

Circadian rhythms

The Eastman group in Chicago studied racial/ethnic differences in the circadian period (tau) (a trait known to have a heritability approaching 100% across vertebrates [71]) and phase shifts across two different races/ethnicities. Participants underwent a forced desynchrony protocol with an ultrashort day length for 3 days [72]. African-Americans were reported to display a shorter average circadian period than European-Americans by around 0.2 h. A subsequent study with increased power, reported a larger difference in circadian period of 0.3 h [1]. To put the magnitude of these difference into perspective, the standard deviation in human circadian period has been reported to be 0.13 h [12]. Differences were also found between African-Americans and European-Americans in the size and direction of phase shift.

A very recent report took advantage of the very substantial UK Biobank dataset (439,933 individuals) [73]. Based on self-reported race/ethnicity, sleep timing and chronotype (based on a single-question), black participants in this UK-based sample had double the prevalence of short sleep duration (5 to 6 hours) and were 1.4 times more likely to characterise themselves as morning or intermediate types than participants describing themselves as white.

Thus, there is evidence that racial/ethnic differences in tau are related to the photoperiod of ancestral origin — African populations close to the equator would have more regular photoperiods than their European counterparts.

Sleep

Sleep duration has repeatedly been found to differ by race/ethnicity. The well-established increased risk of short or long sleep duration in African-Americans as compared to European-Americans [74] has recently also been confirmed in Latinos [75] whereas Chinese-Americans have an increased reported risk of short sleep duration [76]. Another study also reported that African/Caribbean immigrants slept less than European-Americans [77]. A recent Chicago-based epidemiological study compared objectively estimated sleep duration and quality, and subjective sleep quality amongst non-Hispanic whites, African-American, Asian-American and Hispanic/Latinos [78]. All three minority groups had shorter average sleep durations, and African-Americans had poorer objective and subjective sleep quality after adjustment for several sociodemographic and health characteristics.

A meta-analysis of 14 studies (encompassing 4,166 individuals) found that differences in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep latency between African-Americans and European-Americans were only present in community-based studies, but not in studies where participants were examined in a laboratory setting where time in bed is controlled. By contrast, differences in sleep architecture with African-Americans having relatively less slow-wave sleep and more Stage 2 sleep, were consistent regardless of sampling location, with African-Americans having relatively less slow-wave sleep and more Stage 2 sleep [73]. Other studies have reported relatively less slow-wave sleep and more Stage 2 sleep in African-Americans than in European-Americans, and that this difference may be explained in part (but not entirely) by racial discrimination [80,81]. Thus, the published literature suggests that racial/ethnic differences attributable to environmental factors disrupting sleep onset and maintenance may be reversible, whereas differences related to sleep architecture (another highly heritable trait [82]) appear less so. In a more recent community-based study, markers of genetic ancestry were used to determine the relative contributions of African ancestry to sleep architecture in older African-Americans. This study, which controlled for multiple factors including socio-economic status, confirmed the association between higher African ancestry and lower proportion of slow-wave sleep, and did not find any association with sleep duration or efficiency [83,84]

The finding that racial/ethnic differences in sleep parameters attributable to disruptive factors seem to disappear when moving the study from a community setting to a laboratory setting suggests very strongly that some disparities in sleep are, in principle, potentially modifiable if adequate time in bed is possible. Equally, it appears that differences in sleep architecture may have a genetic component. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep-related health outcomes may be attributable, in part, to these differences in sleep, and may, in consequence, be more or less modifiable for the same reasons.

Circadian rhythms and sleep: potential mediators of racial/ethnic disparities in CVD

Circadian rhythms and sleep mediating differences in CVD risk

Considering the substantial evidence of racial/ethnic differences in both studies of sleep and circadian rhythms and in studies of CVD risk, here we present the arguments why sleep and circadian rhythms may be mediating the racial/ethnic disparities in CVD. One cornerstone of such an argument is that coincident differences in circadian rhythm and CVD have been found in specific races/ethnicities. The timing of myocardial infarction (MI) has been found to be ethnicity dependent across Indo-Asians and Mediterranean Europeans. A significantly higher number of acute MI onset occurred between midnight and noon in white and Indo-Asian individuals in the UK). In contrast, Mediterranean Europeans showed the converse pattern, with most of the acute MI events happening between noon and midnight [85]. Similar coincident racial/ethnic differences in cardiovascular function and circadian rhythms have been found elsewhere: African-Americans are more likely to be non-dippers (<10% drop in systolic pressure during sleep) compared to European-Americans, and this difference was exacerbated in night shift workers, suggesting that different race/ethnicities may be differentially impacted by circadian misalignment [86].

Epidemiological evidence suggests racial/ethnic differences in the association between sleep and CVD risk factors as well as CVD-related health outcomes. For example, a crosssectional study of 29,800 individuals in the US National Health Interview Survey found that compared to sleeping 7 to 8 hours, long sleep (>9 h) was associated with a 48% increased risk of being obese for African-Americans whereas for European-Americans long sleep was associated with a 23% decrease in being obese. Compared to those sleeping 7 to 8 hours, African-Americans have a 78% increased odds of being obese with short sleep (<6 h) compared to their American-European counterparts [87]. Data from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found a significant association between shorter self-reported sleep duration and increased BMI in Mexican-Americans but not Cuban-Americans or Puerto Ricans [88]. These results further emphasize that broad heterogeneous racial/ethnic categories, such as Hispanic/Latino, may limit our ability to detect vulnerable groups. Another study that compared six ethnic groups living in the Netherlands reported an unequal association between short sleep and hypertension and dyslipidaemia — where ethnic Dutch and Turks had a greater risk of hypertension, whereas South Asian Surinamese and Moroccans had a greater risk of dyslipidaemia [89]. With respect to CVD outcomes, one US-based cross-sectional study surveyed over 350,000 individuals and identified positive associations between poor subjective sleep quality and chronic heart disease (CHD) and stroke across all racial/ethnic groups [90]. Interestingly, the risk of CHD or stroke was dependent on the number of days for which self-reported insufficient sleep was reported. These data suggested that the association between constant self perceived insufficient sleep (30 days per month without enough rest/sleep) and CHD was stronger in African-Americans and Latinos as opposed to whites (2.06 and 2.22 vs. 1.62) [90].

Potential mechanisms for circadian rhythms and sleep mediating differences in CVD risk

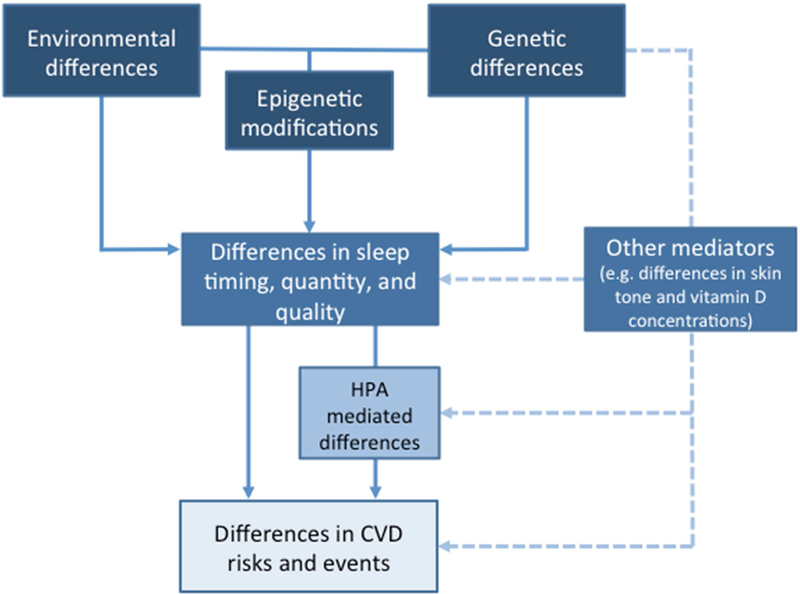

Amongst a range of factors that are more or less attributable to the environment, there remains a core of genetic variability in the fundamental processes of circadian rhythmicity and sleep. The former certainly differ according to racial/ethnic lines; the latter may do so. The same applies to factors underlying cardiovascular health. If the phenotypic intercept between differences in circadian rhythms and sleep and susceptibility to CVD is reflected on the genetic level, then this would mean that gene products could be identified that are of biological importance at the biochemical and/or physiological level as potential mediators of health disparities that could be evaluated both diagnostically and therapeutically. Furthermore, socioeconomic and environmental differences may have fed back into the genome in a stable fashion through epigenetic modifications. The scarcity of evidence about the physiological manifestations of these differences reflects an important and extensive research agenda. We have sought to summarise the major mechanistic strands below and in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Potential biological mechanisms by which racial/ethnic differences in sleep are related to CVD.

Racial/Ethnic differences in CVD outcomes may be directly or indirectly mediated by factors related to sleep and circadian rhythms, which in itself can act via the hippocampal-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis or through alternative mechanisms.

The HPA axis is a strong candidate linking sleep and CVD risk. The relationship between sleep and a number of hormones has been referenced above. Numerous studies have found racial/ethnic differences in these hormones. Longitudinal community based studies have examined cortisol slopes in European-Americans, African-Americans and Latinos over five years found that cortisol slopes differed (African-Americans have flatter slopes), and despite considerable variability in cortisol rhythms from year to year across the sample, racial/ethnic differences remained consistent across the study duration [91].

Studies have also identified racial/ethnic differences in downstream targets of the HPA axis, including blood vessel relativities [92], where arterial stiffness was more pronounced in African-Americans and less pronounced in Amerindians [93] compared to other ethnicities. Ethnic differences in human umbilical vein endothelial cells have also previously been observed, where African-Americans were more likely to have endothelial cells steady states typically associated with cardiovascular disorders [94]. For indirect contributions to cardiovascular differences, one might expect to see ethnic differences in immune cells, liver function, insulin resistance, and in adipose tissue signalling. Indeed, studies have suggested that there are racial/ethnic differences in the accumulation of fat in the liver (Latinos are at a greater risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease compared to African-Americans despite a similar prevalence of risk factors [95]) and storage of visceral fat [96].

To understand whether there are racial/ethnic differences in response to sleep restriction, a recent experimental study examined the effect of acute sleep restriction for five nights followed by one night of recovery sleep on energy intake and expenditure. African-Americans and European-Americans both increased their caloric intake and experienced a decrease in resting metabolic rate after sleep loss, but African-Americans began with a lower resting metabolic rate at baseline. Since both groups consumed an equivalent amount of calories during sleep restriction, it is not surprising that African-Americans gained more weight (1.57 vs. 0.89 kg) [97]. These results suggest that African-Americans may be more susceptible to the effects of sleep loss on obesity risk.

There is also substantial evidence of ethnic differences in immune function. The US-based National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health study [98] suggested poorer immune function in African-Americans. Specifically, they had Epstein-Barr virus antibody levels (an indirect marker of cell mediated immune function) that were 13.6% higher than European-Americans, after adjusting for education and income, whereas no differences were found comparing them with Asians and Latinos. A recent report, based on data from a large multiethnic study [99] investigated the association between elevated C-reactive protein levels (a marker of low-grade systemic inflammation associated with CVD) and a number of candidate genes. A race-combined meta-analysis identified four genetic risk factors for CRP that were unique to African-Americans, whilst others were shared with European-Americans. The former included a novel association at the CD36 locus, whilst the latter included the ARNTL locus, which encodes the BMAL1 protein that is a critical regulator of circadian function. Whilst the latter association does not distinguish between racial/ethnic backgrounds, the role of genes identified in future associations specific to such groups should be evaluated specifically with respect to any functional links with sleep or circadian rhythmicity. Certainly, there are racial/ethnic differences in the frequencies of some key clock gene polymorphisms [100].

A strong case for an HPA-independent mechanistic link was made in a recently reported cross-sectional study where lower concentrations of vitamin D were associated with shorter and poorer sleep. Further, the association between lower concentrations of vitamin D and shorter sleep duration was strongest in African-Americans (compared to Latinos, European-Americans and Chinese-Americans) who also had the lowest levels of vitamin D [101]. This finding suggests the possibility that sleep in individuals with darker skin tone living in areas with lower insolation may be affected by a decreased availability of ultraviolet light for vitamin D synthesis. There is already a well-known association between vitamin D deficiency and CVD events [102]. No mechanism is known for the role of vitamin D in either of these cases; thus, it may or may not be a shared one.

Regardless of the precise mechanism, there appears to be evidence suggesting racial/ethnic differences both at the endocrine and the immunological level in ways that may link circadian and sleep parameters to cardiovascular health. These are likely attributable, to a considerable degree, to underlying socioeconomic factors, but may also reflect smaller, specific genetic differences.

Conclusion and agenda for future research

Components of sleep, circadian rhythms have repeatedly shown a high degree of heritability but autosomal genetic variance polymorphisms examined so far have not as yet accounted for the differences observed [103]. Mapping genetic ancestral markers to sleep and circadian rhythms and CVD would be of considerable utility and this could take advantage of admixture settings where there is often a full spectrum of phonotypical differences [104]. Ultimately, one could build this work further, identifying shared genetic components wherever they may exist across different phonotypical features.

The industrial revolution instigated unparalleled improvements in health and life expectancy, propelling us into the “epidemiological transition”, and CVD will continue to pose a colossal challenge to public health in the years ahead. Considered separately, CVD risk and sleep and circadian rhythms are each known to differ by race/ethnicity. There is strong evidence that poor quality sleep, insufficient duration, and/or mistiming of sleep negatively affects cardiovascular health. Further, there is mounting evidence that race/ethnicity is important for simultaneous changes in risk profile for sleep and CVD. Primarily, this evidence has come from US-based studies where African-Americans are more susceptible to poor sleep, may suffer greater health consequences from sleep equivalent disruptions and are also at higher risk of cardiovascular events. Given that the general population under-reports sleep disturbances, and that African-Americans are associated with an underutilisation of available sleep services [105] there is a serious risk that (even small) ethnic differences in sleep will be exacerbated further in real world settings.

The evidence suggests that interventions aiming to improve sleep behaviour would be beneficial regardless of race/ethnicity; an incremental effect in specific groups could be viewed as an extra bonus at worst. Taking into account the growing global admixture, there is the potential to disentangle sleep contributions to differences in CVD risk profile both by expanding the range of available studies from other continents, by studying race/ethnicity as a continuous rather than a discreet variable, and to build on existing knowledge for ethnic differences at the molecular and cellular level to understand how these differences might occur.

Practice points

A number of studies have suggested ethnic differences in sleep and circadian parameters and CVD. Thus, African-Americans, are more susceptible to poor sleep, are at the greatest risk of cardiovascular events, and are simultaneously associated with an underutilisation of available sleep services.

Lifestyle factors generally associated with cardiovascular health are notoriously difficult to change (e.g. weight, diet, exercise etc.). Sleep is a modifiable lifestyle factor with a potentially higher acceptance. If it is confirmed that racial/ethnic differences in sleep are mediators of racial/ethnic disparities in CVD, it could be exploited for targeted interventions

Research agenda

Further research in this area should focus on

Additional studies to identify whether differences in sleep might contribute to racial/ethnic differences in risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Large cohort studies across multiple geographical settings to identify how sleep patterns vary by culture and environments.

Pool existing data to perform a meta-analysis that inspects the risk factors for CVD, and perform sensitivity analyses for influence of race/ethnicity.

Longitudinal or cross sectional studies conducted in ‘real world’ admixture settings to understand the impact that ethnicity has on the likelihood of CVD events.

Confirming the external validity of racial/ethnic differences in sleep by expanding the studies on the influence of race/ethnicity for sleep and CVD performed outside of the United States.

Exploit datasets from admixed populations for analysis of elements of heritability of CVD and risk factors that co-segregate with ancestral markers.

Targeted studies to elucidate the precise biological mechanisms by which sleep, circadian rhythms, and cardiovascular disease are related, which are still poorly understood, are required for understanding the intercept between racial/ethnic differences and the relationship between sleep and CVD.

More clinical trials which target sleep and circadian rhythm interventions with a view towards improving CVD outcomes

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, 400791/2014–5) and a Global Innovation Initiative award from the British Council and the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (both to MvS). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnoea

- CHD

Chronic heart disease

- HPA

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal

- MI

Myocardial infarction

Glossary

- Admixture

A mixture of different ancestries present within individuals in a population

- Ancestral informative marker (AIM)

A set of polymorphisms at a particular locus which has different frequencies between populations of different geographical origin

- Endophenotype

A distinct phenotype with clear genetic connections

- Race/ethnicity

Two often conflagrated terms, referring to varying degrees to geographical ancestry, physical appearance, and cultural and religious factors. In the context of this review, any and all aspects of these are referred to under this binomial

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- * [1].Eastman CI, Suh C, Tomaka VA, Crowley SJ. Circadian rhythm phase shifts and endogenous free-running circadian period differ between African-Americans and European-Americans. Sci Rep 2015;5:8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Forni D, Pozzoli U, Cagliani R, Tresoldi C, Menozzi G, Riva S, et al. Genetic adaptation of the human circadian clock to day-length latitudinal variations and relevance for affective disorders. Genome Biol 2014;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Omran AR. The Epidemiologic Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of Population Change. Milbank Meml Fund 1971;49:509–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [4].de la Iglesia HO, Fernandez-Duque E, Golombek DA, Lanza N, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA, et al. Access to Electric Light Is Associated with Shorter Sleep Duration in a Traditionally Hunter-Gatherer Community. J Biol Rhythms 2015;30:342–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [5].Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Rathouz PJ, DeLeire T, Lauderdale DS. Trends in the prevalence of short sleepers in the USA: 1975–2006. Sleep 2010;33:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Keyes KM, Maslowsky J, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J. The great sleep recession: changes in sleep duration among US adolescents, 1991–2012. Pediatrics 2015;135:460–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kronholm E, Puusniekka R, Jokela J, Villberg J, Urrila AS, Paunio T, et al. Trends in self-reported sleep problems, tiredness and related school performance among Finnish adolescents from 1984 to 2011. J Sleep Res 2015;24:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eltis D The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Reassessment. William Mary Q 2014;58:14–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bloom DE, Cafiero E, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Reddy Bloom L, Fathima S, et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham Coronary Heart Disease prediction score. Jama 2001;286:180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bitton A, Gaziano T. The Framingham Heart Study’s impact on global risk assessment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;53:68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, et al. Stability, Precision, and Near – 24-Hour Period of the Human Circadian Pacemaker 1999;284:2177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Juda M, Kantermann T, Allebrandt K, Gordijn M, et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock 2007; Sleep Med Rev 11:429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet 1999;354:1435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chatham JC, Young ME. Regulation of Myocardial Metabolism by the Cardiomyocyte Circadian Clock. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013;18:1199–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1989;79:733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wright KP, Bogan RK, Wyatt JK . Shift work and the assessment and management of shift work disorder ( SWD ). Sleep Med Rev 2013;17:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gu F, Han J, Laden F, Pan A, Caporaso NE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Total and Cause-Specific Mortality of U.S. Nurses Working Rotating Night Shifts. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:241–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reutrakul S, Knutson KL. Consequences of Circadian Disruption on Cardiometabolic Health. Sleep Med Clin 2015;10:455–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang X-S, Armstrong MEG, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC, Nicholson PJ. Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2011;61:78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Scheer FAJL Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].McHill AW, Melanson EL, Higgins J, Connick E, Moehlman TM, Stothard ER, et al. Impact of circadian misalignment on energy metabolism during simulated nightshift work. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:17302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [23].Archer SN, Laing EE, Möller-levet CS, Van Der Veen DR, Bucca G, Lazar AS, et al. Mistimed sleep disrupts circadian regulation of the human transcriptome Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;111: E682–E691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Janszky I, Ljung R. Shifts to and from daylight saving time and incidence of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1966–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Arora T, Taheri S. Associations among late chronotype, body mass index and dietary behaviors in young adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yu JH, Yun C-H, Ahn JH, Suh S, Cho HJ, Lee SK, et al. Evening Chronotype Is Associated With Metabolic Disorders and Body Composition in Middle-Aged Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:jc20143754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Garaulet M, Gómez-Abellán P, Alburquerque-Béjar JJ, Lee Y-C, Ordovás JM, Scheer F a JL. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wong PM, Hasler BP, Kamarck TW, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Social Jetlag, Chronotype, and Cardiometabolic Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:4612–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social Jetlag and Obesity. Curr Biol 2012;22:939–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mullington Janet M, Haack Monika, Maria Toth, Serrador Jorge M-EH Cardiovascular, Inflammatory and Metabolic Consequences of Sleep Deprivation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012;51:294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Hulley SB, Liu K, et al. Association between sleep and blood pressure in midlife: the CARDIA sleep study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Malhotra A, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [33].Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, Elia LD, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration, predicts cardiovascular outcomes : a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kasai T, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: A bidirectional relationship. Circulation 2012;126:1495–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schwartz S, Anderson WM, Cole SR, Cornoni-Huntley J, Hays JC, Blazer D. Insomnia and heart disease. J Psychosom Res 1999;47:313–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Platou C, Vatten LJ, Janszky I. Insomnia and the risk of incident heart failure: a population study. Eur Heart J 2013;35:1382–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. J Intern Med 2002;251:207–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ross AJ, Yang H, Larson RA, Carter JR. Sleep efficiency and nocturnal hemodynamic dipping in young, normotensive adults. AJP Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2014;307:R888–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Altman NG, Izci-Balserak B, Schopfer E, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Gehrman PR, et al. Sleep duration versus sleep insufficiency as predictors of cardiometabolic health outcomes. Sleep Med 2012;13:1261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lusardi P, Zoppi A, Preti P, Pesce RM, Piazza E, Fogari R. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure in hypertensive patients: A 24-h study. Am J Hypertens 1999;12:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ogawa Y, Kanbayashi T, Saito Y, Takahashi Y, Kitajima T, Takahashi K, et al. Total sleep deprivation elevates blood pressure through arterial baroreflex resetting: a study with microneurographic technique. Sleep 2003;26:986–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stamatakis KA, Punjabi NM. Effects of Sleep Fragmentation on Glucose Metabolism in Normal Subjects. Chest 2010;137:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rangaraj VR, Knutson KL. Association between sleep deficiency and cardiometabolic disease: implications for health disparities. Sleep Med 2016;18:19–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bose M, Oliván B, Laferrère B. Stress and obesity. Stress Med 1985;1:117–25. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Castro-Diehl C, Roux AVD, Redline S, Seeman T, Shrager SE, Shea S. Association of Sleep Duration and Quality With Alterations in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenocortical Axis : The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis ( MESA ) J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:3149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [46].Möller-Levet CS, Archer SN, Bucca G, Laing EE, Slak A, Kabiljo R, et al. Effects of insufficient sleep on circadian rhythmicity and expression amplitude of the human blood transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2013;110: E1132–E1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, et al. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kaplan JB. The Quality of Data on “Race” and “Ethnicity”: Implications for Health Researchers, Policy Makers, and Practitioners. Race Soc Probl 2014;6:214–36. [Google Scholar]

- [49].AAA Statement on Race. Am Anthropol 1999;100:712–3. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Barbujani G, Ericminch A, Cavalli-Sforza l. L. An apportionment of human DNA diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1997;69:4516–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kaplan JB, Bennett T. Use of race and ethnicity in biomedical publication. JAMA 2003;289:2709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].US Dept. Health Hum. Serv., Natl. Ctr. Health Stat. 2014. Health, United States, 2013: With Special Feature on Prescription Drugs. Hyattsville, MD: US Dept. Health Hum. Serv., Natl. Ctr. Health Stat. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus13.pdfn.d. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chaturvedi N Ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease. Heart 2003;89:681–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sheth T, Nair C, Nargundkar M, Anand S, Yusuf S. Cardiovascular and cancer mortality among Canadians of European, south Asian and Chinese origin from 1979 to 1993: an analysis of 1.2 million deaths. CMAJ 1999;161:132–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mensah GA, Brown DW. An Overview Of Cardiovascular Disease Burden In The United States. 2Health Aff 2007;26:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Halder I, Kip KE, Mulukutla SR, Aiyer AN, Marroquin OC, Huggins GS, et al. Biogeographic Ancestry, Self-Identified Race, and Admixture-Phenotype Associations in the Heart SCORE Study. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Coresh J, Grim CE, Kuller LH. The association of skin color with blood pressure in US blacks with low socioeconomic status. JAMA 1991;265:599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lane DA, Lip GY. Ethnic differences in hypertension and blood pressure control in the UK. QJM 2001;94:391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics−-2015 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. vol. 131 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yu SSK, Castillo DC, Courville AB, Ph D, Sumner AE. The Triglyceride Paradox in People of African Descent. Metab Syndrome Relat Disord 2012;10:77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The Obesity Epidemic in the United States Gender, Age, Socioeconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:6–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too Much Sitting: The Population-Health Science of Sedentary Behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2010;38:105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].August KJ, Sorkin DH. Racial/ethnic disparities in exercise and dietary behaviors of middle-aged and older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Millward D, Karlsen S. Tobacco use among minority ethnic populations and cessation interventions. Race Equality Foundation. London; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jamal A, Homa DM, Connor EO. Great American Smokeout — Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2005 – 2014. Centres Dis Control Prev Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1233–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ford ES, Cooper RS. Implications of Race / Ethnicity for Health and Health Care Use Racial / Ethnic Differences in Health Care Utilization of Cardiovascular Procedures : A Review of the Evidence. Health Serv Res 301 1995;30:237–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Singh GK, Siahpush M, Azuine RE, Williams SD. Widening Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in the United States, Int J MCH AIDS 2015;3:106–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, Mcgee D, Osotimehin B, Kadiri S, et al. The Prevalence of Hypertension in Seven Populations of West African Origin. Am J Public Health 1997;87:160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Dressler WW, Oths KS, Ribeiro RP, Balieiro MC. Cultural Consonance and Adult Body Composition in Urban Brazil. Am J Hum Biol 2008;22:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gravlee CC, Dressler WW. Original Research Article Skin Pigmentation, Self¬Perceived Color, and Arterial Blood Pressure in Puerto Rico. Am J Hum Biol 2005;206:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Helm B, Visser ME. Heritable circadian period length in a wild bird population. Proc R Soc B 2010;277:3335–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Eastman CI, Molina TA, Dziepak ME, Smith MR. Blacks ( African Americans ) Have Shorter Free-Running Circadian Periods Than Whites ( Caucasian Americans ). Chronobiol Int 2012;29:1072–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [73].Malone SK, Patterson F, Lu Y, Lozano A. Ethnic differences in sleep duration, and morning – evening type in a population sample. Chronobiol Int 2016;33:10–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [74].Jean-Louis G, Grandner MA, Youngstedt SD, Williams NJ, Zizi F, Sarpong DF, et al. Differential increase in prevalence estimates of inadequate sleep among black and white Americans. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM. Sleep as a potential fundamental contributor to disparities in cardiovascular health. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:417–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, Lutsey PL, Javaheri S, Alcántara C. Racial / Ethnic Differences in Sleep Disturbances : The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep 2015;38:877–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ertel KA, Berkman LF, Buxton OM. Socioeconomic status, occupational characteristics, and sleep duration in African/Caribbean immigrants and US White health care workers. Sleep 2011;34:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Carnethon MR, De Chavez PJ, Zee PC, Kim K-Y a., Liu K, Goldberger JJ, et al. Disparities in sleep characteristics by race/ethnicity in a population-based sample: Chicago Area Sleep Study. Sleep Med 2016;18:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ruiter ME, Decoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Normal sleep in African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans : A meta-analysis. Sleep Med 2011;12:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Thomas KS, Bardwell W a, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE The toll of ethnic discrimination on sleep architecture and fatigue. Health Psychol 2006;25:635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Tomfohr L, Pung MA, Edwards KM, Dimsdale JE. Racial differences in sleep architecture : The role of ethnic discrimination ξ. Biol Psychol 2012;89:34–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ambrosius U, Lietzenmaier S, Wehrle R, Wichniak A, Kalus S, Winkelmann J, et al. Heritability of Sleep Electroencephalogram. Biol Psychiatry 2008;64:344–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [83].Halder I, Matthews KA, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ, Causer V, Reis SE, et al. African Genetic Ancestry is Associated with Sleep Depth in Older African Americans. Sleep 2015;38:1185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Goel N Parsing Race by Genetic Ancestry. Sleep 2015;38:1151–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].López F, Lee KW, Marín F, Roldán V, Sogorb F, Caturla J, et al. Are there ethnic differences in the circadian variation in onset of acute myocardial infarction? A comparison of 3 ethnic groups in Birmingham, UK and Alicante, Spain. Int J Cardiol 2005;100:151–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Yamasaki F, Schwartz JE, Gerber LM, Warren K, Pickering TG. Impact of Shift Work and Race / Ethnicity on the Diurnal Rhythm of Blood Pressure and Catecholamines. Hypertension 1998;32:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Donat M, Brown C, Williams N, Pandey A, Racine C, McFarlane SI, et al. Linking sleep duration and obesity among black and white US adults. Clin Pr 2013;10:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Knutson KL. Association between sleep duration and body size differs among three Hispanic groups. Am J Hum Biol 2011;23:138–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Anujuo K, Stronks K, Snijder MB, Jean-louis G. Relationship between short sleep duration and cardiovascular risk factors in a multi-ethnic cohort – the helius study. Sleep Med 2015;16:1482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Vishnu A, Shankar A, Kalidindi S. Examination of the Association between Insufficient Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes by Race/Ethnicity. Int J Endocrinol 2011;2011:789358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].DeSantis AS, Adam EK, Hawkley L, Cacioppo JT. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Diurnal Cortisol Rhythms: Are They Consistent Over Time? Psychosom Med 2015;77:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Wesley N, Maibach H. Racial (Ethnic) Differences in Skin Properties. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:843–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].de Lima Santos PCJ, de Oliveira Alvim R, Ferreira NE, de Sa Cunha R, Krieger JE, Mill JG, et al. Ethnicity and Arterial Stiffness in Brazil. Am J Hypertens 2011;24:278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Kalinowski L Race-Specific Differences in Endothelial Function: Predisposition of African Americans to Vascular Diseases. Circulation 2004;109:2511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Guerrero R, Vega GL, Grundy SM, Browning JD. Ethnic differences in hepatic steatosis: An insulin resistance paradox? Hepatology 2009;49:791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Lear SA, Humphries KH, Kohli S, Chockalingam A, Frohlich JJ, Birmingham CL. Visceral adipose tissue accumulation differs according to ethnic background: Results of the Multicultural Community Health Assessment Trial (M-CHAT). Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Spaeth AM, Dinges DF, Goel N. Resting Metabolic Rate Varies by Race and by Sleep Duration. Obesity 2015;23:2349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Dowd JB, Palermo T, Chyu L, Adam EK, McDade TW. Race/ethnic and socioeconomic differences in stress and immune function in The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med 2014;115:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Ellis J, Lange EM, Li J, Dupuis J, Baumert J, Walston JD, et al. Large multiethnic Candidate Gene Study for C-reactive protein levels : identification of a novel association at CD36 in African Americans Hum Genet 2014;133::985–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Nadkarni NA, Weale ME, Schantz M Von, Thomas MG. Evolution of a Length Polymorphism in the Human PER3 Gene, a Component of the Circadian System J Biol Rhythm 2005;20:490–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * [101].Bertisch SM, Sillau S, Boer IH De, Szklo M, Redline S. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration and Sleep Duration and Continuity: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep 2015;38:1305–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Mheid I Al Patel RS, Tangpricha V Quyyumi AA. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: is the evidence solid? Eur Heart J 2013;34:3691–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Kripke DF, Kline LE, Nievergelt CM, Murray SS, Shadan FF, Dawson A, et al. Genetic variants associated with sleep disorders. Sleep Med 2015;16:217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Goetz LH, Uribe-Bruce L, Quarless D, Libiger O, Schork NJ. Admixture and Clinical Phenotypic Variation. Hum Hered 2014;77:73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, Dharawat A, Lazar JM, Brown CD. Evaluation of sleep apnea in a sample of black patients. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4:421–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]