Abstract

Human liver glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (hlGPDH) catalyzes the reduction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to form glycerol 3-phosphate, using the binding energy associated with the nonreacting phosphodianion of the substrate to properly orient the enzyme-substrate complex within the active site. Herein, we report the crystal structures for unliganded, binary E•NAD, and ternary E•NAD•DHAP complexes of wild type hlGPDH, illustrating a new position of DHAP, and probe the kinetics of multiple mutant enzymes with natural and truncated substrates. Mutation of Lys120, which is positioned to donate a proton to the carbonyl of DHAP, results in similar increases in the activation barrier to hlGPDH-catlyzed reduction of DHAP and to phosphite dianion activated reduction of glycolaldehyde, illustrating that these transition states show similar interactions with the cationic K120 side chain. The K120A mutation results in a 5.3 kcal/mol transition state destabilization, and 3.0 kcal/mol of the lost transition state stabilization is rescued by 1.0 M ethylammonium cation. The 6.5 kcal/mol increase in the activation barrier observed for the D260G mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reaction represents a 3.5 kcal/mol weakening of transition state stabilization by the K120A side chain, and a 3.0 kcal/mol weakening of the interactions with other residues. The interactions, at the enzyme active site, between the K120 side chain and the Q295 and R269 side chains was likewise examined by double mutant analyses. These results provide strong evidence that the enzyme rate acceleration is due mainly or exclusively to transition state stabilization by electrostatic interactions with polar amino acid side chains.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION.

Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH, UNIPROT P21695) is a dimer that catalyzes hydride transfer from NADH to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to form L-glycerol 3-phosphate (L-G3P, Scheme 1).1–4 This enzyme utilizes binding energy of the phosphodianion of whole substrate DHAP and of phosphite dianion piece in the stabilization of the transition state for GPDH-catalyzed reactions of the whole substrate DHAP and the truncated substrate glycolaldehyde (GA, Scheme 1).5, 6 The phosphodianion and phosphite dianion binding energies are similar to those determined for the reactions of whole and truncated substrates catalyzed by orotidine monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC)7 and triosephosphate isomerase (TIM).8

Scheme 1.

We are working to develop a structure-based model for dianion activation of GPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer. A comparison of the X-ray crystal structures for the binary hlGPDH•NAD (1X0X, 2.75 Å resolution) and the ternary hlGPDH•NAD•DHAP (1WPQ, 2.50 Å resolution) complexes of hlGPDH show that the binding of substrate DHAP is accompanied by an enzyme conformational change in which a flexible protein loop [292-LNGQKL-297] folds over the side chain of R269 that interacts directly to form an ion pair with the phosphodianion, and which is locked into place over the phosphodianion by a hydrogen bond to Q295 in the flexible loop.4 The neighboring amide side chain from N270 also interacts with this dianion. We have used these X-ray crystal structures to target R269,9 N270,10 and Q29511 for mutagenesis studies and in the interpretation of the results from these studies.

One notable feature of the published structure of human GPDH4 is that the DHAP ligand appears in two conformations within the two independent chains of the asymmetric unit. These conformations present different re and si faces of the DHAP carbonyl group to the hydride donor NADH, so that only one conformation may undergo direct hydride transfer to form the physiological product L-G3P. Examination of 1WPQ shows that the positions of the protein and NAD cofactor are clearly defined by the electron-density, the electron density for the DHAP ligand at the two chains is ambiguous. We therefore recognized that structures of the wild type enzyme determined at a higher resolution and more complete electron density for trapped substrates would provide a more accurate description of this position of the amino acid side chains at the enzyme active site, improving the analysis of on-going mutagenesis studies.

We report here X-ray crystal structures of unliganded and liganded forms of hlGPDH at resolutions of 1.9 −2.1 Å. The new structures show the same ligand driven conformational change in conformation from an open to closed form identified previously,4 and only a single binding conformation for DHAP at the nonproductive ternary E•NAD•DHAP complex. The carbonyl oxygen of DHAP is within hydrogen bonding distance of K120 and K204, consistent with a role for these side chains in stabilizing negative charge at this oxygen at the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer from NADH. However, the new structure for the ternary complex suggests that only the alkyl ammonium cation of K120 is positioned to function as a Brønsted acid and donate a proton to substrate carbonyl oxygen.

These high resolution X-ray crystal structures are used in the interpretation of results from studies on following site-directed mutants of hlGPLH: (a) Mutants of K120, the side chain implicated in Brønsted acid catalysis at the carbonyl oxygen; and, of D260 whose side chain anion forms an ion pair to the cationic K120 side chain. (b) Second mutations at a K120A mutant that probe the interactions between the side chains of K120 and of D260, R269,9 or Q295.11 The results demonstrate an important role for K120 in catalysis of hydride transfer, and define the catalytic role of the interactions of K120 with several nearby side chains at the enzyme active site.

EXPERIMENTAL.

Materials.

Water was purified using Milli-Q Academic purification system. Q-Sepharose and Sephacryl S-200 were purchased from GE Healthcare. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced (NADH, disodium salt), dihydroxyacetone phosphate lithium salt, triethanolamine hydrochloride (≥ 99.5%), ampicillin, isopropyl ß-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), kanamycin, ammonium chloride, methylammonium chloride, ethylammonium chloride, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid sodium salt (MES, ≥99.5%) and glycolaldehyde (dimer) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pierce protease inhibitor, EDTA free was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Bovine serum albumin, fraction V (BSA) was purchased from Roche. Ammonium sulfate (enzyme grade), sodium hydroxide (1.0 N) and hydrochloric acid (1.0 N) were purchased from Fisher. Sodium phosphite was purchased from Fluka. Quikchange II Site – Directed Mutagenesis Kits were purchased from Agilent Technologies. All chemicals were reagent grade or better and were used without further purification.

Preparation of Solutions.

Stock solutions of TEA and MES buffers were prepared by dissolving the solid in the appropriate amount of water, and adjusting the solution to the desired pH using 1.0 N HCl or 1.0 N NaOH. Ionic strength was adjusted by adding solid NaCl. Stock solutions of ampicillin (100 mg/mL) and kanamycin (50 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving the solid in water and filtering the solution through a 0.2 micron syringe filter. Ampicillin and kanamycin are stored at –20 °C. Stock solutions of NADH were prepared by dissolving the solid cofactor in water. The concentration of NADH was determined by taking the absorbance at 340 nm and using the molar absorptivity value of 6220 M–1 cm–1. Stock solutions of BSA (10 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving the solid in water. Stock solutions of DHAP were prepared by dissolving lithium salt of DHAP in water, adjusting the pH to 7.5 using 1.0 N HCl, and storing the solution at –20 °C. The concentration of DHAP was determined as the concentration of NADH consumed during an hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction. Stock solutions of glycolaldehyde and phosphite dianion were prepared by published methods.12

Cloning and Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Human Liver Glycerol Phosphate Dehydrogenase.

The plasmid pDNR-dual donor vector containing the gene for wild type hlGPDH gene insert was purchased from the Harvard plasmid repository. The insert gene was subcloned into a bacterial expression vector pET-15b from Novagen and used for mutagenesis. Site-directed mutagenesis on pET-15b to introduce the mutations was carried out using the Quikchange II kit from Stratagene. The primers used to introduce base changes encoding for the K120A, D260G, R269A and Q295A mutants differ from the sequence for the wild type gene as follows:

K120A Mutants: —

Wild type: 5’-CTGGCATATCTCTTATTAAGGGGGTAGACGAGGGC-3’

K120A: 5’-CTGGCATATCTCTTATTGCGGGGGTAGACGAGGGC-3’

D260G Mutants: —

Wild type: 5’-GAGAGCTGTGGTGTTGCTGACCTGATCACTACCTGCTATG-3’

D260G: 5’-GAGAGCTGTGGTGTTGCTGGCCTGATCACTACCTGCTATG-3’

R269A Mutants: —

Wild type: 5´-CCTGCTATGGAGGGCGGAACCGGAAAGTGGCTGAGGCC-3´

R269A: 5´-CCTGCTATGGAGGGGCGAACCGGAAAGTGGCTGAGGCC-3´

Q295A Mutants: —

Wild type: 5′-GAAAGAGTTGCTGAATGGGCAGAAACTGCAGGGGCCCGAG-3′

Q295A: 5′-GAAAGAGTTGCTGAATGGGGCAAAACTGCAGGGGCCCGAG-3′

The K120 and D260 mutants were constructed individually, by published procedures,11 starting with 20 ng of plasmid pET-15b containing the gene for wild type hlGPDH that had been purified from Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The K120A/D260G, K120A/R269A and K120A/Q295A double mutants were constructed as follows: (a) DNA from the D260G mutant plasmid was used as the template for insertion of the K120A primer in preparing the K120A/D260G double mutant; (b) DNA from the K120A mutant plasmid was used as the template for insertion of the R269A and Q295A primers in preparing the K120A/R269A and K120A/Q295A double mutants, respectively.

Protein Expression and Purification.

The GPDH-deficient glpD1 strain from the Escherichia coli Keio collection was purchased from the Coli Genetic Stock Center at Yale University. Lysogenization of this strain was carried out using a λDE3 lysogenization kit from Novagen. The plasmids coding for single K120A and D260G mutants and the K120A/D260G, K120A/R269A, K120A/Q295A double mutants of hlGPDH were transformed separately into freshly lysogenized competent Escherichia coli glpD1 (DE3) cells. The cells containing the mutant plasmid were grown overnight in 200–300 mL of LB medium that contained 100 µg/mL ampicillin and 50 µg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C. This culture was diluted into 5 L of LB medium (100 µg/mL ampicillin and 50 µg/mL kanamycin), and grown at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.6, at which point 0.6 mM isopropyl-1-thio-D-galactoside was added and the temperature adjusted to 19 °C to induce protein expression. After 12–18 hours of overexpression, the cells were harvested and stored in 20 mL of 25 mM MES buffer that contains 150 mM NaCl at pH 6.8. The cell pellets were suspended in 25 mM MES at pH 6.8 in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete®) and lysed using a French press.

The following procedures for purification of these mutants were adapted from published procedures for the wild type enzyme.4 The harvested cells were lysed and the cell debris removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was diluted to 60 mL final volume with 25 mM MES at pH 6.8 that contains 30 mM NaCl. The nucleic acids removed by treatment with 10% (w/v) PEI and centrifugation. The protein mixture was subjected to 30%, 40%, 50% and 60% fractional precipitation with ammonium sulfate. The pellet that contains hlGPDH was identified and was purified by column chromatography as described in the Supporting Information to this manuscript.

hlGPDH-Catalyzed Reduction of DHAP.

The hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH was assayed in solutions that contain 20 mM TEA (pH 7.5), 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 100 or 200 µM NADH, 0.04–15 mM DHAP at I = 0.12 (NaCl) and the following enzyme concentrations: K120A, 0.1 – 0.5 μM; D260G, 0.5 µM; K120A/D260G, 5 µM; K120A/R269A; 20 µM; K120A/Q295A; 2 µM. The initial velocity v for the reduction of DHAP was determined from the change in absorbance at 340 nm over a 5 – 20 minute reaction time for all hlGPDH mutants except K120A/R269A which was monitored for over 60 – 300 minutes. The kinetic parameters kcat and Km for the mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reactions were determined from the fit of the plot of v/[E] against [DHAP] to the Michaelis-Menten equation, where [DHAP] is the concentration of the carbonyl form of DHAP that is present as 55% of total DHAP.13

The K120A and D260G mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH in the presence of alkylammonium cations or formate anion, respectively, was assayed in solutions that contained 20 mM TEA buffer (pH 7.5), 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 200 µM NADH, 0.5–5 mM DHAP, 20–80 mM alkyl ammonium cation hydrochloride or 10–60 mM sodium formate at I = 0.12 (NaCl). The initial velocity v for the reduction of DHAP was determined from the change in absorbance at 340 nm over a 5 −10 minute reaction time.

K120A hlGPDH-Catalyzed Reduction of Glycolaldehyde (GA) by NADH.

The K120A mutant-catalyzed reduction of glycolaldehyde was monitored in solutions that contained 10 mM TEA (pH 7.5), 0.9–3.6 mM glycolaldehyde, 0.20 mM NADH, 0–30 mM phosphite dianion and 30 µM K120A at I = 0.12 (NaCl). The initial velocity v for the reduction of the carbonyl form GA was determined from the change in absorbance at 340 nm over a 240 minute reaction time. The concentration of the carbonyl form of GA was calculated from the total concentration of GA using fcar = 0.06.12 There was no significant change in absorbance (∆A340 ≤ 0.010) observed for the K120A mutant-catalyzed reduction of glycolaldehyde in the absence of phosphite dianion over a 240 minute reaction time. This sets an upper limit of kcat/Km ≤ 0.003 M−1 s−1 for K120A GPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA by NADH.

Protein Crystallization.

The lead conditions for crystallization of unliganded and the binary NAD complex of hlGPDH were identified using the high throughput screening crystallization service at the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute.14 Final conditions were optimized by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals of the unliganded and the NAD complex of hlGPDH were grown in 175 mM potassium chloride, 23% PEG 20000, 0.1 M bis-Tris propane at pH 7.0 at 10 mg/mL of protein, and with 10 mM NAD for the complex. The crystal growth was judged to be complete after 24 hours at 14 °C. The crystals were mounted on nylon loops and cryoprotected by serial passage through a crystallization cocktail that was supplemented with 7.5%, 15%, and 30% (v/v) pentaerythritol propoxylate (PEP-426)15 [unliganded hlGPDH], or with 8%, 16% and 24 % (v/v) ethylene glycol and 1.0 mM NAD [binary hlGPDH•NAD complex]. The crystals were frozen by plunging in liquid nitrogen.

The crystallization conditions for the dead end hlGPDH•NAD•DHAP ternary complex were identified using an in-house sparse-matrix hanging-drop, vapor-diffusion screen of hlGPDH that was preincubated with 2 mM NAD and 1 mM DHAP. The optimized crystallization solution contained 100 mM calcium chloride, 20% polyethylene glycol (PEG 8000), 5% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), 50 mM bis-Tris propane pH 7.0 and 10 mg/mL hlGPDH. The crystal growth was judged to be complete after 24 hours at 14 °C. After ca 7 days, crystals were mounted on nylon loops and cryoprotected by serially transferring crystals through crystallization cocktail supplemented with increasing amounts of MPD (8%, 16%, and 24%), 2.2 mM NAD and 1.1 mM DHAP. The mounted crystals were cryocooled in liquid nitrogen.

Data Collection and Refinement.

The data sets from X-ray diffraction were collected remotely at either the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory or the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. These data were processed using iMosflm.16 The structure for the binary complex with NAD was solved by molecular replacement using the N-and C-terminal domains from hlGPDH (PDB ID 1X0X) as a search model. The resulting output model was used for continued cycles of manual model building and refinement using Coot17, 18 and PHENIX19. The structure for the ternary complex was solved in two steps as described in the results Section. The structure for unliganded enzyme was solved by molecular replacement using the protein atoms from the binary model described above. The data collection and refinement statistics are reported in Table S1 and S2 of the Supporting Information.19 Using MOLPROBITY to detect Ramachandran outliers, D44 is identified in the unliganded structure and V92 is identified in chains A & C of the ternary structure. D44 is located on a poorly ordered loop however the density was deemed adequate for inclusion in the final model. In the ternary model, the electron density for V92 is excellent; the reason for that the torsion angles position this residue just outside the allowed region is not clear. The final structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 6E8Y (unliganded), 6E8Z (binary complex), and 6E90 (ternary complex).

RESULTS

X-Ray Crystallographic Analyses.

hlGPDH•NAD Complex.

The binary hlGPDH•NAD complex was the first protein structure solved. This complex crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21, with two protein chains in the asymmetric unit (Table S1). The structure was solved by molecular replacement with human cytosolic GPDH complexed with NAD (PDB ID 1X0X).4 After initial attempts at molecular replacement with 1X0X failed, manual inspection identified a single loop that separated the two domains, suggesting that the two domains might adopt a different orientation in our model compared to the prior structure. We therefore divided the search model into two fragments at residue 201. This molecular replacement procedure with the two partial models resulted in suitable LLG values and electron density maps of excellent quality, with changes in the orientation between the two major protein lobes as described below. The final structure for the binary complex contained 338 of 349 residues in chain A, and 340 of 349 residues in chain B. The conserved gaps across the two chains included residues 1, 122–128, and 293. Chain A showed an additional disordered region for residues 46 and 47. The final model also contained two potassium ions, two phosphate anions of uncertain origin, and four molecules of the cryoprotectant ethylene glycol, where ethylene glycol at chain A occupies the phosphodianion binding site.

Ternary hlGPDH•NAD•DHAP Complex.

We next solved the structure of the ternary hlGPDH•NAD•DHAP complex obtained by co-crystallization of the protein in the presence of saturating concentrations of NAD (1 mM) and DHAP (2 mM). The protein crystallized in the triclinic P1 space group with 4 chains in the asymmetric unit (Table S1). Molecular replacement by the binary hlGPDH•NAD complex positioned the four chains; two with excellent electron density for the length of the protein, and two with poor density for the C-terminal half of the protein. Repeating molecular replacement using the protein atoms from the published ternary complex of hlGPDH (PDB ID 1WPQ) again identified four chains, but a with a different pair of chains showing poor density for the C-terminal domain. We concluded that the asymmetric unit consists of two protein chains in the closed conformation observed in 1WPQ and two chains in the new conformation similar identified for our binary complex. Superposition of the open conformation of chain D into the position of chains A or B identified clashes with a neighboring molecule suggesting that crystal packing likely supports the mixed conformations that were identified. Combining the two high-quality protein chains obtained from the separate molecular replacements give four chains that fit the electron-density throughout, and that were refined to completion.

The final structure for the unit cell of the crystals grown in a solution that contains DHAP and NAD shows true ternary complexes for the closed forms of chains A and B; chain C in the open form with only NAD bound; and, chain D in the open form with no discernable ligands (Figure S1). NAD and DHAP bound to the A and B chains were refined to 100 % occupancy, whereas the NAD at chain C was first manually examined at 0.5 (50%) occupancy in the coordinates file, and with further refinement was solved at an optimal 0.7 (70%) occupancy. We refer to the entire structure from crystals grown in the presence of NAD and DHAP as the “ternary complex”. Table 1 lists the number of total residues for this ternary complex, as well as disordered, unmodeled regions. Two of each of the following ligands from the crystallization cocktail and cryoprotectant were identified at this structure: Ca2+, inorganic phosphate, and 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD).

Table 1.

The Bound Ligands and the Total Amino Acids Modeled (349 Total Residues) for the Four Chains of the Ternary Complex Structure of hlGPDH.

| Chain | Ligands | Total residues modeled | Unmodeled residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | NAD, DHAP | 344 | 1, 244‒247 |

| B | NAD, DHAP | 345 | 1‒2, 246‒247 |

| C | NAD | 344 | 1‒2, 347‒349 |

| D | None | 335 | 1, 44‒49, 56–57, 127‒128, 348–349 |

Unliganded hlGPDH.

Finally, crystals of wild type hlGPDH in the absence of ligands were grown in the monoclinic space group P21, with two protein chains in the asymmetric unit (Table S1). This protein structure was solved by molecular replacement, using the coordinates of the binary NAD complex (see above) as a search model. The final model contained 344 of 349 residues in chain A, and 340 of 349 residues in chain B. Both chains are missing the initial methionine as well as several disordered loops. Chain A has a single disordered region, residues 46–49, while residues 123–128 and 294–295 are disordered by Chain B. The following ligands from the crystallization cocktail and cryoprotectant were identified at this structure: two K+ ions, pentaerythritol, presumably derived from the pentaerythritol propoxylate, and one inorganic phosphate ion.

Structure of hlGPDH.

The new structures illustrate that hlGPDH adopts two different conformations (Figure 1). The existence of the conformational change was inferred previously from the homologous enzyme from L. mexicana (lmGPDH) however all previously reported structures of the human liver hlGPDH were in the closed conformation. We report the open conformation observed in the unliganded and binary complex. Only in the presence of both NAD and DHAP, as seen in chains A and B of the ternary complex, does the enzyme adopt a closed conformation in which the two domains form multiple contacts.

Figure 1.

Conformational change of GPDH. The open (cyan) and closed (tan) conformations of GPDH were aligned on the basis of the Cα positions within the N-terminal domain, residues 2–191 using chain A of the unliganded structure and chain A of the ternary complex. The domain closure is indicated with the arrow. The Figure was generated with PyMol.20

To characterize the net effect of this conformational change on protein structure, we examined the RMS displacement (RMSD) of the α-amino carbons (Cα ) in the protein chains for structures of the open and closed forms of hlGPDH (Table 2). The similar RMSD of 0.47 Å for chains A of unliganded hlGPDH and the binary complex to NAD shows that there is a minimal protein conformational change associated with the binding of NAD to hlGPDH. Chains A and B of the ternary complex to hlGPDH show excellent electron density for DHAP and NAD. The RMSD of Cα for these two chains is 0.41 Å for residues 3–349; the conformation and orientation of NAD and DHAP bound at the two chains are identical. There is a large 2.66 Å RMSD of Cα for chains A of the ternary complex and the binary NAD complex. This shows that hlGPDH undergoes a large conformational change upon binding of DHAP to the binary complex, to adopt the closed conformation observed for previous structures of hlGPDH at lower resolution.4 Chain C for the ternary complex structure shows electron density of 0.7 mol of NAD, a 1.02 Å RMSD for overlay of the Cα of chain A from the binary complex structure, but a large 2.51 Å RMSD for overlay on chain A of the ternary complex. A similar trend in these RMSDs is observed for overlay of the Cα of chain D for the ternary complex structure on chain A for the unliganded, binary NAD or ternary complex structures.

Table 2.

Comparison of the RMS displacement of Cα positions for current and published structures of human hlGPDH. RMS Displacement was calculated by SSM Superpose in Coot.18

| RMS Displacement (Å, Cα Positions) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (Chain) | Conformation | Ligand | Unliganded (A) | Binary (A) | Ternary (A) | Ternary (D) | 1WPQ (A) |

| Unliganded (A) | Open | -- | -- | ||||

| Binary (A) | Open | NAD | 0.47 | -- | |||

| Ternary (A) | Closed | NAD/DHAP | 2.83 | 2.66 | -- | ||

| Ternary (D) | Open | -- | 0.66 | 0.92 | 3.07 | -- | |

| 1WPQ (A) | Closed | NAD/DHAP | 2.94 | 2.78 | 0.84 | 3.09 | -- |

| 1X0V (A) | Closed | -- | 2.76 | 2.64 | 1.25 | 2.93 | 0.97 |

The closed form of hlGPDH from the ternary complex was similar to the published 2.5 Å resolution closed form 1WPQ (chain A) with a Cα RMSD of 0.84 Å for residues 2–349. Both structures have superimposable regions, including the “clamp” residues 292–298, denoting the closed form in this case. The conformation and orientation of the enzyme-bound NADs are almost identical, with an RMSD of 0.39 Å for all atoms in the molecule. The structure of the ternary complex of hlGPDH with NAD and DHAP provided clear electron density for a single binding conformation of DHAP in contrast to the two alternate conformations observed in the earlier structure (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Representations of chain A for the closed ternary complex with bound NAD and DHAP. Simulated annealing omit map density was calculated for the ligands and contoured at 3.0 σ (A) Stereoimage of side chains that interact with DHAP. (B) Hydrogen bonds (dashed gray lines) of DHAP with amino acid side chains and enzyme bound waters (red spheres). (C) Overlay of ternary complexes that shows the relative positions of DHAP and protein at the structure reported here (beige) and at the two positions from the previously reported structure 1WPQ (light and dark blue).

Kinetic Parameters for Mutant hlGPDG.

The K120A, D260G, K120A/D260G, K120A/R269A and K120A/Q295A mutants of hlGPDH were prepared by standard methods,9, 10 and their kinetic parameters determined at 25 °C, pH 7.5 (20 mM TEA buffer) and I = 0.12 (NaCl). GPDH follows an ordered reaction mechanism with NADH (Kd = 7 µM)21 binding first, followed by DHAP.22 We find in all cases that the Michaelis-Menten plots of initial velocity data for mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reductions of DHAP in the presence of 0.10 and 0.20 mM NADH show a good fit to a single set of kinetic parameters kcat and Km and conclude that 0.20 mM NADH is saturating for these mutant enzymes. The kinetic parameters for mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reactions of DHAP were therefore determined at saturating 0.20 mM [NADH]. Figure 3 shows Michaelis-Menten plots of v/[E] against [DHAP] for: (a) reduction of DHAP by NADH (200 µM) catalyzed by K120A and D260G mutants of hlGPDH (Figure 3A); reduction of DHAP catalyzed by K120A/D260G and K120A/Q295A mutants (Figure 3B); and, reduction of DHAP catalyzed by the K120A/R269A mutant (Figure 3C). The kinetic parameters for these mutant enzyme-catalyzed reactions were obtained from nonlinear least squares fits of these data to the Michaelis-Menten equation for Scheme 2, and are reported in Table 3. Table 3 also gives kinetic parameters for wild type, R269A, Q295A and R269A/Q295A hlGPDH determined in earlier work.9, 11

Figure 3.

Michaelis-Menten plots of v/[E] against [DHAP] for reduction of DHAP by NADH (0.2 mM) catalyzed by hlGPDH mutants at 25 °C, pH 7.5 (20 mM TEA buffer) and I = 0.12 (NaCl). 3A: (■), K120A mutant; (●), D260G. 3B: (●), K120A/Q295A; (■) K120A/D260G. 3C: (●), K120A/R269A mutant.

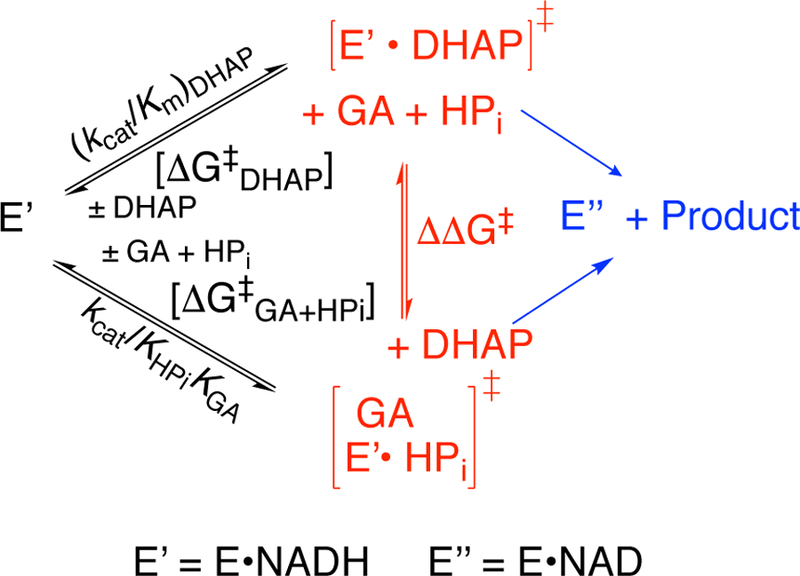

Scheme 2.

Kinetic Mechanism for Wild type and Mutant hlGPDH-Catalyzed Reduction of DHAP at Saturating Concentrations of NADH.

Table 3:

Kinetic Parameters for Wild type and Mutant hlGPDH-Catalyzed Reduction of DHAP by NADH at pH 7.5 and I = 0.12.

| Enzyme | kcat/s−1 a | Km/M a | (kcat/Km)/M−1 s−1 a | ΔΔG‡ b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT c | 240 ± 10 | (5.2 ± 0.3) x 10−5 | (4.6 ± 0.3) x 106 | |

| R269Ad | (5.9 ± 0.4) x 10−3 | (5.7 ± 0.5) x 10−3 | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 9.1 |

| Q295Ae | 100 ± 10 | (1.6 ± 0.2) x 10−3 | (6.3 ± 1.0) x 104 | 2.5 |

| K120A | 0.87 ± 0.01 | (1.6 ± 0.2) x 10−3 | 550 ± 30 | 5.3 |

| D260G | 0.13 ± 0.01 | (1.9 ± 0.2) x 10−3 | 70 ± 12 | 6.5 |

| R269A/Q295A | (3.7 ± 0.4) x 10−3 | (4.9 ± 0.5) x 10−4 | 7.5 | |

| K120A/D260G | (7.1 ± 0.2) x 10−3 | (1.6 ± 0.2) x 10−3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 8.3 |

| K120A/R269A | (8.3 ± 1.1) x 10−5 | (1.3 ± 0.3) x 10−2 | (6.2 ± 0.4) x 10−3 | 12 |

| K120A/Q295A | (2.4 ± 0.3) x 10−2 | (1.2 ± 0.3) x 10−2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 8.7 |

Kinetic parameter determined from the fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The quoted errors are the average of the values determined from at least two sets of data for hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by 0.10 and 0.20 mM NADH (Figure 3).

The calculated interaction between the side-chain(s) and transtion states for GPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer.

Ref 5.

Ref 9.

Ref 11.

Figures 4A and 4B show the effect of increasing [EtNH3+] and [NH4+], respectively, on v/[E] for K120A mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH (200 µM) at 25 °C, pH 7.5 (20 mM TEA buffer) and I = 0.12 (NaCl). The values of (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) for reactions in the presence of different fixed [RNH3+] were determined as the slopes of these linear correlations. Figure 4C shows the effect of increasing [NH4+] or [EtNH3+] on (kcat/Km)obs for rescue of the K120A mutant hlGPDH by RNH3+. The slope of these linear correlations is (kcat/Km)am/KRNH3 = (1.2 ± 0.1) x 104 and (8.5 ± 0.4) x 104 M−2 s−1(Scheme 3). respectively, for activation of K120A reduction of DHAP by [NH4+] and [EtNH3+]. The rescue of the activity of the D260G mutant enzyme by formate anion was also examined.23 A small 20% decrease in v/[E] was observed as [HCO2-] was increased from 0 −0.060 M [data not shown] for D260G mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of 0.5 mM DHAP by NADH (200 µM) at 25 °C, pH 7.5 (20 mM TEA buffer) and I = 0.12 (NaCl).

Figure 4.

Effect of increasing [RNH3+] on v/[E] (s−1) for K120A mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH for reactions a pH 7.5 (20 mM TEA buffer), 25 °C, a saturating NADH concentration of 0.2 mM, and I = 0.12 (NaCl): (A) EtNH3+: (▲), 80 mM cation; (◆), 60 mM cation; (▼), 40 mM cation; (■), 20 mM cation; (●), no cation. (B) NH4+: (▲), 80 mM cation; (◆), 60 mM cation; (▼), 40 mM cation; (■), 20 mM cation; (●), no cation. (C) Effect of increasing [RNH3+] on the values of (kcat/Km)obs from panels A and B: (●) NH4+ and (■) EtNH3+.

Scheme 3.

Kinetic Mechanism for Activation of K120A Mutant hlGPDH by RNH3+.

Figure 5A shows the increase in v/[E] for the reduction of GA by NADH (0.20 mM) catalyzed by K120A hlGPDH (30 µM) with increasing [HPi] at pH 7.5 (10 mM TEA), 25 ºC and I = 0.12. The slopes of these linear correlations are equal to the apparent second-order rate constants (kcat/KHPi)obs. Figure 5B shows the plot of values of (kcat/KHPi)obs from Figure 5A against the concentration of the free carbonyl form of GA. The fit of these data to eq 1, derived for Scheme 4, gave values of KGA = 3.5 mM and kcat/KHPiKGA = 0.92 M−2 s−1 for activation of K120A hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by phosphite dianion. The value of kcat/KHPiKGA = 16000 M−2 s−1 was previously reported for activation of the wild type hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA by NADH.5

Figure 5.

Phosphite dianion activated K120A mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA at pH 7.5 (10 mM TEA buffer), 25 °C and saturating [NADH] = 0.2 mM. (A) The effect of increasing [HPO32-] on v/[E] for reduction of a constant concetration of GA. The slope of the individual correlation is equal to (kcat/KHPi)obs. Key: (●), 0.90 mM GA; (■), 1.8 mM GA; (◆), 2.7 mM GA; (▲), 3.6 mM GA. (B) Plot of the values of (kcat/KHPi)obs from Figure 5A against the concentration of the free carbonyl form of glycolaldehyde. These data were fit to eq 1, as described in the text.

Scheme 4.

Kinetic Mechanism for Phospite Dianion Activated Reduction of GA at Saturating Concentrations of NADH Catalyzed by Wild type and Mutant hlGPDH.

| (1) |

DISCUSSION

We report here the structure for wild type hlGPDH, at a significantly higher resolution (2.05 Å) than for the previously published structure (2.5 Å).4 We previously emphasized the motion of a single enzyme loop in describing the ligand-driven conformational change of hlGPDH.11 However, the crystal structures reported here and in earlier work show that this conformational change also involves a larger motion about a hinge that connects the C-terminal and N-terminal domains. This was decribed previously for lmGPDH as an 11° hinge motion, based on a comparison of the structures modeled for the unliganded protein and the ternary complex.24 The conformations observed for the binary and ternary complexes of hlGPDH show an even larger hinge motion of 22°, using the DYNDOM web server.25 The closed states of lmGPDH and hlGPDH are similar, so that the larger hinge motion observed for hlGPDH reflects the more open conformation for the binary E•NAD complex for hlGPDH compared with unliganded lmGPDH.

A comparison of the open binary E•NAD and the closed nonproductive E•NAD•DHAP ternary complexes shows the following changes that will strongly favor hydride transfer on the productive E•NADH•DHAP complex (Figure 6): (a) The development of strong dianon interactions that involve the R269, N270 and Q295 side chains. (b) Movement of the K120 side chain from the Rossman-fold domain into a position to donate a proton to the carbonyl oxygen. (c) Movement of the bound cofactor towards the substrate carbonyl. (d) The development of interations with a long a-helix (residues 255 to 280) at the C-terminal domain (see next paragraph). (e) Sequestration of DHAP in a protein cage, that provides strong stabilization of a charged intermediates by interactions with polar amino acid side chains.26, 27 This ligand-driven conformational change conforms to Koshland’s induced fit model, where protein-ligand interactions act to mold flexible unliganded GPDH into a stiff active conformation.28, 29

Figure 6.

A representation of the X-ray crystal structure of the nonproductive ternary complex between hlGPDH, DHAP and NAD (PDB entry 6E90), which shows the following highly conserved amino acid side chains:24 (a) R269 and N270 that interact with the substrate phosphodianion; (b) Q295, from a flexible enzyme loop, which interacts with R269. (c) K120 and K204, that are positioned to interact with the carbonyl oxygen. (d) N205, T264 and D260, which are part of a network of hydrogen bonded side chains that connect the catalytic and dianion activation sites of hlGPDH.

Finally, the C-terminal domain of hlGPDH contains a long helix (residues 255–280) that is interrupted by a kink at G267 and G268. This kink positions the main chain amides of G267 and G268 to interact with the substrate phosphodianion and directs residues R269-T280, that define a positive N-terminus helix dipole, towards the substrate phosphodianion. A check of the SWISS-PROT database shows that the G267GRN270 sequence is conserved, even in GPDH sequences that share as little as 40% sequence identity. However, the bacterial and lower eukaryotic GPDH sequences lack the GG motif, but show the same helix disruption, resulting from an insertion of two residues, as seen in the crystal structure of GPDH from L. mexicana.24

Conformation of DHAP at the ternary complex.

Different conformations for the DHAP ligand were modeled at the two protein chains in the previously published 2.5 Å structure of the nonproductive ternary E•NAD•DHAP complex.4 These conformations present different faces of the carbonyl group of DHAP to the nicotinamide ring, so that hydride transfer would result in formation either L-G3P (observed) or D-G3P. The carbonyl oxygen at DHAP likewise shows different positions relative the highly conserved alkyl ammonium cation side chains of K120 and K204, which are candidates to interact with the substrate C-2 oxygen during hl-GPDH catalyzed reduction of DHAP.24

The structure of the nonproductive E•NAD•DHAP complex reported here at 2.05 Å resolution (Figures 2 and 6) shows electron density for a single orientation of DHAP that exposes the si-face of the carbonyl group to hydride transfer from NADH. The carbonyl carbon of DHAP is positioned 3.4 Å from the nicotinamide hydride donor in the two chains. The carbonyl oxygen and C-1 OH of DHAP both lie within hydrogen bonding distance of cationic side of the K120 (2.6 Å) and K204 (2.8 Å) cationic side chains (Figure 2B). However, the Nε of K120 lies nearly coplanar with the plane defined by the trigonal C=O bond, and is well positioned to provide formal Brønsted acid catalysis by protonation of this oxygen, while the Nε of K204 lies well below this plane, and is judged less likely to participate in protonation of the carbonyl oxygen (Figures 2 and 6).

K120.

We judge the K120 side chain from the N-terminal Rossman-fold domain to be favorably placed to interact in a hydrogen bond with the nonbonded electrons at the carbonyl oxygen (Figure 6), and have examined the effect of a K120A mutation on the enzyme catalyzed hydride transfer to whole and truncated substrates.5, 9, 10, 30 This mutation results in a total 5.3 kcal/mol destabilization of the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP, that is partitioned between a 2.0 kcal/mol effect on the stability of the Michaelis complex (Km effect, Table 1) and a 3.3 kcal/mol increase in the barrier to conversion of this complex to the rate-determining transition state (kcat effect). The effect of the K120A mutation on Km is due partly or entirely to the loss of a stabilizing hydrogen bond between the alkyl ammonium side chain and the oxygen of the C-1 hydroxyl of DHAP.

The K120A mutation results in a large decrease in the third-order rate constant kcat/KHPiKGA for dianion activation of hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA (Scheme 5) that corresponds to a 5.8 kcal/mol transition state destabilization. Figure 7 compares the effect of K120A and Q295X mutations of hlGPDH on log (kcat/Km)DHAP and log (kcat/KHPiKGA) for catalysis of reduction of the whole substrate and the substrate pieces.11 These data show a good fit to a linear correlation with a slope of 1.09 ± 0.03 (r = 0.997), that reflects the nearly constant difference of ΔΔG‡ = (3.5 ± 0.2) kcal/mol in the activation barriers for the hlGPDH-catalyzed reactions of the whole substrate DHAP and the substrate pieces GA + HPi (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

A Comparison of the Activation Barriers for the GPDH-Catalyzed Reactions of the Whole Substrate DHAP and the Substrate Pieces GA + HPi.

Figure 7.

Linear logarithmic correlation for reactions catalyzed by wild type and mutants of hlGPDH, with slope of 1.09 ± 0.03, between second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)DHAP for catalysis of reduction of the whole substrate DHAP and third-order rate constants (kcat/KHPiKGA) for phosphite dianion activation of hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA.

Linear free energy correlations with slope 1.0 have likewise been reported for kinetic parameters for reactions of whole substrates and substrates pieces catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase [TIM, ΔΔG‡ = 6.6 kcal/mol]31, 32 and by orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase [OMPDC, ΔΔG‡ = 4.5 kcal/mol].33 The slopes of 1.0 show that the enzymatic transition states for these reactions of whole substrate and substrate pieces are stabilized by essentially the same interactions between the enzyme-bound dianion and the protein catalyst. This is consistent with a model where phosphite dianion participates actively to hold hlGPDH in an active, high-energy, closed conformation but is otherwise a spectator anion at the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer.

Third-order rate constants of (kcat/Km)RNH3/KRNH3 = (1.2 ± 0.1) x 104 and (8.5 ± 0.4) x 104 M−2 s−1, respectively, were determined for rescue of the K120A mutant by [NH4+] and [EtNH3+] (Figure 4). Eq 2, derived for Scheme 6, was used to calculate (ΔG‡act)am, the stabilizing interaction between RNH3+ activators and the transition state for hydride transfer from NADH to DHAP, as illustrated graphically by Scheme 7. Scheme 7 also shows: [(Δ(G† )K120A − (Δ(G† )WT) = 5.3 kcal/mol, the effect of the K120A mutation on stability of the wild type transition state and, (b) Δ(GD†) is the apparent advantage for connection of ammonium cation to the whole enzyme. The poor efficiency for rescue of the K120A mutant of hlGPDH by by NH4+ compared to EtNH3+ (Scheme 7) was also observed in an earlier study on the activation of the K12G mutant of TIM.34 This is due to the combined effects of the stronger aqueous solvation of NH4+ compared to EtNH3+;35 and, the stronger stabilization of the Michaelis complex to EtNH3+ by hydrophobic interactions with the alkyl side chain.

Scheme 6.

Mechanism for Activation of the K120A Mutant of hlGPDH by Ammonium Cations.

Scheme 7.

Comparison of Total Transition State Stabilization by the Cationic Side Chain of K120 and From Rescue of the K120A Mutant by Amine Cations.

| (2) |

D260.

The side chain ions of D260 and K120 are separated by 2.9 Å at the active site of hlGPDH (Figure 6), so that the carboxylate anion side chain of D260 functions to hold the cationic side chain of K120 close to the DHAP carbonyl group. The 6.5 kcal/mol destabilization of the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by the D260G mutation is larger than the 5.3 kcal/mol effect of the K120A mutation. This shows that D260, which lies in the second shell of side chains that surround DHAP, plays a larger role in maintaining full enzymatic activity than first shell side chain K120. There is no significant rescue of the D260G mutant by 60 mM formate anion, in contrast to the effective rescue of the K120A mutation by EtNH3+. Figure 8 shows that rescue is possible for the K120 side chain, which is partly exposed to solvent at the binary E•NAD complex, but not for the D260 side chain that lies buried underneath K120.

Figure 8.

The surface structure of the binary complex between hlGPDH and NAD (green spheres), which shows the alkyl group of K120 shaded red and the ammonium cation shaded blue.

Interactions between side chains.

The total stabilization of the transition state for GPDH catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH reflects the total interactions between the individual active site side chains and the transition state. However, the stabilizing interactions between a single amino acid side chain and the enzyme-bound transition state will likely be influenced by interaction of the side chain with its neighbors at the enzyme active site. We have examined the effect of second D260G, R269A and Q295A mutations of K120A mutant hlGPDH on the interactions between the K120A and the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP.

K120A/D260G (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Cycles that show the effect of consecutive mutations on the activation barrier for wild type hlGPDH-catalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH. (A) Consecutive mutations of K120A and D260G. (B) Consecutive mutations of K120A and Q295A. (C) Consecutive mutations of K120A and R269A.

These following results show that the second-shell side chain of D260 plays an important role in maintaining the structural integrity of the active site of hlGPDH. (a) The 5.3 kcal/mol and 1.8 kcal/mol effects (Figure 9A) of the K120A mutation on the stability, respectively, of the transition state for wild type and D260G mutant hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer reactions are consistent with a 3.5 kcal/mol decrease in transition state stabilization by the K120A side chain at D260G mutant. The total 6.5 kcal/mol effect of the D260G mutation is therefore divided between a 3.5 kcal/mol effect on the transition state stabilization by interaction with the K120 side chain and a 3.0 kcal/mol effect that arises from structural changes at the enzyme active site, which weakens transition state stabilization from interaction with other side chains. (b) The total 8.3 kcal/mol destabilization of the transition state for wild type hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer determined for the K120A/D260A mutant may likewise be divided the 5.3 kcal/mol stabilizing interaction from the K120 side chain plus the additional 3.0 kcal/mol decrease in transition state stabilization by interactions with other side chains.

K120A/Q295A (Figure 9B).

Figure 9B shows that the effect of K120A and Q295A mutations on the stability of the transition state for the wild type hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer is similar to their effect on transition state stability for hlGPDH previously mutated at the second side chain. In other words, there is no detectable interaction between K120A and Q295A so that a mutation of one side chains does not affect transition state stabilization by the second side chain.

K120A/R269A (Figure 9C).

The R269A mutation results in a large 9.1 kcal/mol transition state destabilization, while the double K120A/R269A mutation results in an total 13.0 kcal/mol destabilization of the transition state for hlGPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer that is ca. 10% smaller than 14.4 kcal/mol, the sum of the effect of single K120A and R269A mutations (Figure 9C). This difference represents only a slight weakening in the interaction of the remaining side chain upon mutation of K120 or R269, so that the side chains act nearly independently in stabilization of the hydride transfer transition state. We showed previously that the side chains from N270 and Q295 are required to obtain the large 9.1 kcal/mol transition state destabilization from R269 side chain cation.11

Comparisons with Other Dehydrogenases.

Other dehydrogenases from Homo sapiens also maintain structural similarity to GPDH, including alcohol (PDB code 1HSO),36, 37 lactate (1I0Z, 4OJN),38, 39 glucose-6-phosphate (6E08),40, 41 isocitrate (4L06),42, 43 and UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (2Q3E).44, 45 All these dehydrogenases have less than or equal to 20% sequence identity to GPDH, yet contain the relevant Rossmann fold for cofactor binding. In addition, most are found in open and closed conformations.37, 39, 42–44 Not all of them are dimers like GPDH,40, 44 and the role of lysine in the active site can be found as a general base.43 Although the active site architecture and thereby substrate specificities may vary from one dehydrogenase to the next, the overall folds are similar.

It was proposed that NAD-dependent dehydrogenases “have evolved by exon-shuffling by which an exon encoding for the NAD-binding domain was fused to a different exon encoding the C-terminal domain providing a different substrate specificity.” 24 If correct, then the conformationally mobile C-terminal and NAD-binding domains at unliganded dehydrogenases may provide only a low catalytic activity for reduction of nonspecific substrates, while binding interactions of these elements with specific substrates, such as the interaction of GPDH with the substrate phosphodianion, are required to draw these enzymes into a catalytically active conformation.28, 29

This proposal is supported by the results of a recent structural characterization of three opine dehydrogenases (ODH) isolated from bacterial pathogens: yersinopine dehydrogenase (YpODH, from Y. pestis ), pseudopaline dehydrogenase, (PaODH, from P. aeruginosa), and staphylopine dehydrogenase (SaODH, from S. aureus).46 Each ODH consists of three domains; an N-terminal NADPH-binding domain, a C-terminal catalytic domain for substrate binding, and a third domain, which serves as the dimer interface. These ODH, NADPH-binding and catalytic domains, are separated by a ≈ 7800 Å3 central crevice, that is estimated to place the transferred hydride of the nicotinamide ring ≈ 8.5 Å distant from the catalytic domain.46 This large separation is incompatible with a high activity for ODH, so that the binding interactions with the respective bound substrates must be utilized to draw each enzyme into its reactive conformation, as described here for the dianion binding inteactions of GPDH.

The Rate Acceleration for GPDH and Other Dehydrogenases.

The value of kcat/Km = (6.2 ± 0.4) x 10−3 determined for the K120A/R269A mutant hlGPDH-calalyzed reduction of DHAP by NADH is only 100-fold larger than (6.7 ± 0.3) x 10−5 M−1 s−1 for nonenzymatic reduction of a benzaldehyde-type carbonyl group tethered to RNA by exogenous NADH.47 This shows that a large fraction of the rate acceleration of hlGPDH can be accounted for largely by the focused transition state stabilization obtained from interactions with these two cationic side chains that are promoted by neighboring, highly conserved amino acid side chains, including D260, N270, Q295, and its associated loop.9–11, 48 This analysis provides strong evidence that the rate acceleration for GPDH is due largely to transition state stabilization by electrostatic interactions with polar amino acid side chains, and that these strong binding interactions require a high degree of organization of amino acid side chains at the enzyme active site.49, 50

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS.

The X-ray crystal structures reported for unliganded, binary E•NAD, and ternary E•NAD•DHAP complexes of hlGPDH at 1.9 −2.1 Å are similar to earlier stuctures reported on 2.5 Å,4 except that the ternary complex shows only a single conformation of enzyme bound DHAP, that differs from the alternate conformations observed in the earlier structures. The side chain cations of K120 and K204 lie within hydrogen bonding distance of the carbonyl oxygen, but the side chain of K120 sits in the plane of this carbon-oxygen π-bond and appears optimally placed to donate a proton to this oxygen at the alkoxide product of hydride transfer from NADH to DHAP. The results of mutagenesis of side chains at the catalytic site (K120) and dianion activation site (R269 and Q295) provide strong support for the proposal that the enzymatic rate acceleration for GPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer is due mainly or excusively to transition state stabilization by electrostatic interactions with polar amino acid side chains.51 The catalytic role of K204, within the larger framework of the network of side chains at the enzyme active site, remains to be determined.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

This work is funded in part by grant from the NIH (AI116998 to A.M.G. and GM116921 to J.P.R), and additionally by support from the Swedish Research Council (VR, Grant 2015-04928 to S.C.L.K). Work at the GM/CA@APS has been funded in in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The Eiger 16M detector was funded by an NIH-Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, High-End Instrumentation Grant (1S10OD012289-01A1). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393).

ABBREVIATIONS.

- OMPDC

orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase

- TIM

triosephosphate isomerase

- GPDH

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hlGPDH

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from human liver

- DHAP

dihydroxyacetone phosphate

- GA

glycolaldehyde

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, oxidized form

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- TEA

triethanolamine

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Description of the procedures for purification of mutants of hlGPDH by column chromatograhy over Sephacryl S-200. Table S1: Data collection statistics for structural determinations of unliganded hlGPDH and binary and ternary hlGPDH complexes. Table S2: Data refinement statistics for structural determinations. Figure S1: Electron density of the active sites of chains C and D from the ternary complex, PDB 6E90.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bentley P, and Dickinson FM (1973) Kinetics and mechanism of action of rabbit muscle L-α-glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase, Biochem. Soc. Trans 1, 663–665. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bentley P, and Dickinson FM (1974) Coenzyme-binding characteristics of rabbit muscle L-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Biochem. J 143, 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bentley P, Dickinson FM, and Jones IG (1973) Purification and properties of rabbit muscle L-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Biochem. J 135, 853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ou X, Ji C, Han X, Zhao X, Li X, Mao Y, Wong L-L, Bartlam M, and Rao Z (2006) Crystal structures of human glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (GPD1), J. Mol. Biol 357, 858–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Reyes AC, Zhai X, Morgan KT, Reinhardt CJ, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2015) The Activating Oxydianion Binding Domain for Enzyme-Catalyzed Proton Transfer, Hydride Transfer and Decarboxylation: Specificity and Enzyme Architecture, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 1372–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tsang W-Y, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2008) A Substrate in Pieces: Allosteric Activation of Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (NAD+) by Phosphite Dianion, Biochemistry 47, 4575–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Amyes TL, Richard JP, and Tait JJ (2005) Activation of orotidine 5’-monophosphate decarboxylase by phosphite dianion: The whole substrate is the sum of two parts, J. Am. Chem. Soc 127, 15708–15709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Morrow JR, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2008) Phosphate Binding Energy and Catalysis by Small and Large Molecules, Acc. Chem. Res 41, 539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reyes AC, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2015) Enzyme Architecture: Optimization of Transition State Stabilization from a Cation–Phosphodianion Pair, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 5312–5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2016) Enzyme Architecture: A Startling Role for Asn270 in Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase-Catalyzed Hydride Transfer, Biochemistry 55, 1429–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].He R, Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2018) Enzyme Architecture: The Role of a Flexible Loop in Activation of Glycerol-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase for Catalysis of Hydride Transfer, Biochemistry 57, 3227–3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2007) Enzymatic catalysis of proton transfer at carbon: activation of triosephosphate isomerase by phosphite dianion, Biochemistry 46, 5841–5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Reynolds SJ, Yates DW, and Pogson CI (1971) Dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Its structure and reactivity with α-glycerolphosphate dehydrogenase, aldolase and triose phosphate isomerase and some possible metabolic implications., Biochem. J 122, 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Luft JR, Collins RJ, Fehrman NA, Lauricella AM, Veatch CK, and DeTitta GT (2003) A deliberate approach to screening for initial crystallization conditions of biological macromolecules, J. Struct. Biol 142, 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gulick AM, Horswill AR, Thoden JB, Escalante-Semerena JC, and Rayment I (2002) Pentaerythritol propoxylate: a new crystallization agent and cryoprotectant induces crystal growth of 2-methylcitrate dehydratase, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58, 306–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, and Leslie AG (2011) iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schrodinger LLC. (2015) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8.

- [21].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2016) Structure-Reactivity Effects on Intrinsic Primary Kinetic Isotope Effects for Hydride Transfer Catalyzed by Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 14526–14529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Black WJ (1966) Kinetic studies on the mechanism of cytoplasmic L-α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase of rabbit skeletal muscle, Can. J. Biochem & Phys 44, 1301–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Richard JP, Huber RE, Heo C, Amyes TL, and Lin S (1996) Structure-reactivity relationships for β-galactosidase (Escherichia coli, lac Z). 4. Mechanism for reaction of nucleophiles with the galactosyl-enzyme intermediates of E461G and E461Q β-galactosidases, Biochemistry 35, 12387–12401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Choe J, Guerra D, Michels PAM, and Hol WGJ (2003) Leishmania mexicana glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase showed conformational changes upon binding a bi-substrate adduct, In J. Mol. Biol, pp 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [25].Girdlestone C, and Hayward S (2016) The DynDom3D Webserver for the Analysis of Domain Movements in Multimeric Proteins, J. Comp. Biol 23, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Richard JP, Amyes TL, Goryanova B, and Zhai X (2014) Enzyme architecture: on the importance of being in a protein cage, Curr. Op. Chem. Biol 21, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2010) A role for flexible loops in enzyme catalysis, Curr. Op. Struct. Biol 20, 702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thomas JA, and Koshland DE Jr. (1960) Competitive inhibition by substrate during enzyme action. Evidence for the induced-fit theory, J. Am. Chem. Soc 82, 3329–3333. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Koshland DE Jr. (1958) Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 44, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2016) Enzyme Architecture: Self-Assembly of Enzyme and Substrate Pieces of Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase into a Robust Catalyst of Hydride Transfer, J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 15251–15259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhai X, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2015) Role of Loop-Clamping Side Chains in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 15185–15197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhai X, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2014) Enzyme Architecture: Remarkably Similar Transition States for Triosephosphate Isomerase-Catalyzed Reactions of the Whole Substrate and the Substrate in Pieces, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 4145–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goldman LM, Amyes TL, Goryanova B, Gerlt JA, and Richard JP (2014) Enzyme Architecture: Deconstruction of the Enzyme-Activating Phosphodianion Interactions of Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 10156–10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Go MK, Koudelka A, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2010) Role of Lys-12 in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach, Biochemistry 49, 5377–5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brauman JI, and Blair LK (1971) Gas-phase acidities of amines, J. Am. Chem. Soc 93, 3911–3914. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Niederhut MS, Gibbons BJ, Perez-Miller S, and Hurley TD (2001) Three-dimensional structures of the three human class I alcohol dehydrogenases, Protein Sci 10, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Plapp BV (2010) Conformational changes and catalysis by alcohol dehydrogenase, Arch Biochem Biophys 493, 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Read JA, Winter VJ, Eszes CM, Sessions RB, and Brady RL (2001) Structural basis for altered activity of M-and H-isozyme forms of human lactate dehydrogenase, Proteins 43, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kolappan S, Shen DL, Mosi R, Sun J, McEachern EJ, Vocadlo DJ, and Craig L (2015) Structures of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in apo, ternary and inhibitor-bound forms, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hwang S, Mruk K, Rahighi S, Raub AG, Chen CH, Dorn LE, Horikoshi N, Wakatsuki S, Chen JK, and Mochly-Rosen D (2018) Correcting glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency with a small-molecule activator, Nat Commun 9, 4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bautista JM, Mason PJ, and Luzzatto L (1995) Human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Lysine 205 is dispensable for substrate binding but essential for catalysis, FEBS Lett 366, 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rendina AR, Pietrak B, Smallwood A, Zhao H, Qi H, Quinn C, Adams ND, Concha N, Duraiswami C, Thrall SH, Sweitzer S, and Schwartz B (2013) Mutant IDH1 enhances the production of 2-hydroxyglutarate due to its kinetic mechanism, Biochemistry 52, 4563–4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Aktas DF, and Cook PF (2009) A lysine-tyrosine pair carries out acid-base chemistry in the metal ion-dependent pyridine dinucleotide-linked beta-hydroxyacid oxidative decarboxylases, Biochemistry 48, 3565–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Egger S, Chaikuad A, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, and Nidetzky B (2011) Structure and mechanism of human UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase, J Biol Chem 286, 23877–23887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Egger S, Chaikuad A, Klimacek M, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, and Nidetzky B (2012) Structural and kinetic evidence that catalytic reaction of human UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase involves covalent thiohemiacetal and thioester enzyme intermediates, J Biol Chem 287, 2119–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].McFarlane JS, Davis CL, and Lamb AL (2018) Staphylopine, pseudopaline, and yersinopine dehydrogenases: A structural and kinetic analysis of a new functional class of opine dehydrogenase., J Biol Chem 293, 8009–8019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tsukiji S, Pattnaik SB, and Suga H (2004) Reduction of an Aldehyde by a NADH/Zn 2+-Dependent Redox Active Ribozyme, J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 5044–5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2018) Primary Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects: A Probe for the Origin of the Rate Acceleration for Hydride Transfer Catalyzed by Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 57, 4338–4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, and Parson WW (2006) Modeling electrostatic effects in proteins, Biochim Biophys Acta -Prot. & Proteom 1764, 1647–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Warshel A (1998) Electrostatic Origin of the Catalytic Power of Enzymes and the Role of Preorganized Active Sites, J. Biol. Chem 273, 27035–27038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, and Richard JP (2017) A reevaluation of the origin of the rate acceleration for enzyme-catalyzed hydride transfer, Org. & Biomol. Chem 15, 8856–8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.