Abstract

Dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs) mediate many of the actions of dopamine in the striatum, ranging from movement to the effortful pursuit of reward. Yet despite significant advances in linking D2Rs to striatal functions with pharmacological and genetic strategies in animals, how dopamine orchestrates its myriad actions on different cell populations —each expressing D2Rs— remains unclear. Furthermore, brain imaging and genetic studies in humans have consistently associated striatal D2R alterations with various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, but how and which D2Rs are involved in each case is poorly understood. Therefore, a critical first step is to engage in a refined and systematic investigation of the impact of D2R function on specific striatal cells, circuits, and behaviors. Here, I will review recent efforts, primarily in animal models, aimed at unlocking the complex and heterogeneous roles of D2Rs in striatum.

Introduction

Nearly 60 years since it was first demonstrated to be a neurotransmitter (Carlsson et al., 1957), dopamine (DA) is now known to be critical for numerous functions like motor behavior, reward, cognition, metabolism and hormonal secretion (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). Dysfunction of the DA system has been implicated in various disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia and addiction (Albin et al., 1989; Laruelle, 1998; Snyder, 1976; Volkow et al., 2009; Volkow et al., 2007).

DA is synthesized by tyrosine hydroxylase-containing dopaminergic neurons in various areas of the brain, including key areas such as the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA), as well as in the locus coeruleus, hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray (Yetnikoff et al., 2014). Despite relatively small numbers of DA neurons in these areas, their axonal projections are numerous and widespread throughout the brain (Trudeau et al., 2014).Of those, DA neurons from the SNc send their densest projection to dorsal striatal regions, while the VTA preferentially targets the ventral striatum, including the nucleus accumbens (NAc)(Morales and Margolis, 2017; Trudeau et al., 2014).

While somatodendritic release has been documented, most DA release sites occur along axons and are predominantly non-synaptic or asynaptic (Trudeau et al., 2014). DA may also be released at different timescales and in response to different DA neuron firing patterns (Grace et al., 2007). Furthermore, subpopulations of DA neurons may exhibit unique electrophysiological and pharmacological properties (Morales and Margolis, 2017). Accumulating evidence also supports the ability of DA to be co-released with other neurotransmitters such as glutamate and GABA, further emphasizing the intricate nature of dopamine neuron-derived signals in the brain (Trudeau et al., 2014). The complex neuroanatomical and functional organization leading to DA synthesis and release is matched by DA’s actions on its different receptors, pre- and postsynaptically.

The DA D2 receptor (D2R) has been well-established as a critical mediator of dopamine actions in striatum. Here, I will review some of the unique challenges surrounding D2Rs that have both excited and puzzled researchers for several decades. I will also provide an update on recent endeavors aimed at elucidating its diverse contributions to striatal function and dopamine-dependent behaviors.

Dopamine receptor classes

DA exerts its neurochemical influence on cells through its actions on two main families of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs): the D1 receptor (D1R) and the D2 receptor (D2R) families.The D1R family is composed of D1R and D5R, whereas the D2R family consists of D2R, D3R, and D4R. D1Rs and D2Rs have been the most widely studied, in part because they are the most densely expressed throughout dorsal and ventral striatum, but also due to their contrasting regulation of cellular signaling and activity. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that the other receptor subtypes (D3-D5R) also play key roles in shaping striatal functions (Centonze et al., 2003; Cote et al., 2014; Dulawa et al., 1999; Rubinstein et al., 1997; Simpson et al., 2014; Song et al., 2012).

Classically, the D1R family activates the Gαs/olf family of G proteins, leading to activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) and increased cAMP production, whereas the D2R class recruits Gαi/o signaling to inhibit AC and cAMP production (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). In striatal spiny projection neurons (SPNs), these well-studied signaling pathways are known to influence protein kinase A (PKA) activity as well as the phosphorylation state of various proteins. One such protein, DARPP-32, acts as a signal transduction integrator to modulate the activity of key kinases and phosphatases, altering neuronal excitability and gene expression (Svenningsson et al., 2004).

Dopamine receptors may modulate the function of various ion channels through Gα-mediated mechanisms but also via Gβγ subunits, effectively regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels and excitability in striatal neurons (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). A vast body of work using electrophysiological recordings in acute neuronal or slice preparations has demonstrated that in SPNs, pharmacological activation of D1Rs and D2Rs generally elicits the opposite effects on the function of L-type calcium channels, K+ channels, and on the trafficking and function of glutamatergic α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors (Cepeda et al., 1993; Galarraga et al., 1997; Greif et al., 1995;Hallett et al., 2006; Hernandez-Echeagaray et al., 2004; Hernandez-Lopez et al., 1997;Hernandez-Lopez et al., 2000; Kitai and Surmeier, 1993; Snyder et al., 2000; Surmeier et al.,1995). D1R activation is thus thought to favor increased excitability and heightened Ca2+ entry into SPNs, while the opposite is generally assumed following D2R activation, but the outcome may differ depending on the state of the cell, as well as on recording conditions (Nicola et al., 2000).

D1 and D2Rs also may signal via G-protein independent mechanisms. One such mechanism involves the β-arrestins. While primarily known for their roles in desensitization and internalization of GPCRs, β-arrestins may also engage various signaling cascades (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011; Shenoy and Lefkowitz, 2011). In response to dopamine binding, for example, dopamine receptors recruit β-arrestins (β-arrestin-1 and −2), which terminates G protein signaling and facilitates receptor endocytosis (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011; Kim et al., 2001). Based on several in vivo studies, it has been proposed that D2Rs promote, via β-arrestin-2, the inactivation of Akt and the subsequent activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), whereas D1Rs preferentially activate β-arrestin-2-mediated ERK signaling (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Beaulieu et al., 2004; Beaulieu et al., 2007; Urs et al., 2011).

Localization of D2 receptors in striatum

One characteristic of D2Rs that has complicated their study is their expression in multiple neuronal populations within striatum, both pre- and postsynaptically (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). In addition to spiny projection neurons (SPNs), which are the principal cells of the striatum, D2R expression has been demonstrated in cholinergic interneurons (CINs), as well as in axon terminals of DA and cortical neurons, all of which are key players in controlling striatal output and behavior.

Spiny projection neurons

In dorsal striatum, expression of D1R and D2R is largely restricted to one of two subsets of SPNs (Beckstead, 1988; Frederick et al., 2015; Gerfen et al., 1990; Le Moine and Bloch, 1995; Surmeier et al., 1996; Yung et al., 1995). The D1R-expressing SPNs are typically those of the “direct pathway”, sending direct axonal projections to the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) and the internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi). Conversely, SPNs enriched in D2Rs convey their signals to the midbrain via multiple synapses through the external segment of the GP (GPe), and are thus referred to as the “indirect pathway.” These neuroanatomical differences have functional consequences, as direct and indirect pathways exert opposite effects on thalamo-cortical activation. Often referred to as “Go” and “NoGo” pathway, direct and indirect pathways have been a subject of intense investigation, particularly in the context of motor regulation and Parkinson’s disease (Albin et al., 1989). More recently, optogenetics and chemogenetic studies in mice have offered confirmation for the divergent functions of these pathways. In the dorsomedial striatum, for example, artificial stimulation of the direct pathway promotes locomotion, whereas activation of the indirect pathway inhibits locomotion (Cazorla et al., 2014; Kravitz et al., 2010). Nevertheless, accumulating evidence has shown that both pathways are activated during movement initiation (Cui et al., 2013).

Histological estimates in BAC transgenic mouse lines show that D1R and D2R are co-expressed in 2–6% of all SPNs in dorsal striatum and within the NAc core subregion (Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2008; Frederick et al., 2015; Gallo et al., 2015). In the NAc shell, this co-expression appears to be relatively higher, ranging from 5 to 17% (Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2008; Frederick et al., 2015).

Direct and indirect pathways analogous to those in dorsal striatum have also been described in the NAc (Heimer et al., 1991; Ikemoto, 2007; Zahm, 1989). However, the segregation of the neuroanatomical and functional projections of the two pathways appears to be less complete in the NAc than in dorsal striatum (Kupchik et al., 2015; Lu et al., 1998). Like dorsal striatal D2R-expressing SPNs (D2-SPNs) that innervate the GPe, NAc D2-SPNs project mainly to the ventral pallidum (VP). Yet, in NAc, a substantial proportion of D1-expressing SPNs (D1-SPNs) innervate the VP, in addition to their direct projections to the output nuclei (Kupchik et al., 2015; Lu et al., 1998). Thus, the interchangeable categorizing of D1R and D2R-expressing SPNs of the NAc as “direct” and “indirect” pathways has been questioned (Kupchik et al., 2015). The outcome of dopamine’s actions on striatal circuits, thus, will depend not only on the subset of SPN (D1R vs D2R-expressing) being targeted, but also on the regional context in which those SPNs function. Adding another layer of region-specific complexity in studying DA receptors is that dopaminergic inputs also feature substantial phenotypic and topographical diversity (Morales and Margolis, 2017).

In striatum, ultrastructural studies have shown D2Rs to be primarily found postsynaptically in SPNs, often associated with membranes in dendritic spines, dendrites and cell bodies (Sesack et al., 1994; Yung et al., 1995). Consistent with this localization, some physiological studies have documented an inhibitory influence of acute D2R agonism on SPN excitability measured at the soma (Hernandez-Lopez et al., 2000; Onn et al., 2003). D2R immunoreactivity is also found in GABAergic terminals within the VP, some of which are likely D2-SPN terminals (Mengual and Pickel, 2002), supporting pharmacological work that suggested a presynaptic role for D2R on D2-SPN-to-GPe projections (Floran et al., 1997). Besides long-distance projections to pallidal regions, D2-SPNs also send local axonal collaterals which contact other SPNs (Tunstall et al., 2002; Wilson and Groves, 1980). As will be discussed in more detail in the subsequent sections, growing functional evidence from both dorsal and ventral striatal preparations, supports a presynaptic role for D2R on regulation of SPN-to-SPN neurotransmission (Cooper and Stanford, 2001; Dobbs et al., 2016; Gallo et al., 2018; Kohnomi et al., 2012).

Cholinergic interneurons

Another cell that expresses D2Rs is the cholinergic interneuron (CIN)(Dawson et al., 1988; Le Moine et al., 1990; Yan et al., 1997). While only constituting 1–3% of all striatal neurons, CINs have dense axonal arborizations and are a major source of striatal acetylcholine (ACh)(Kreitzer, 2009). CINs participate in variety of striatal functions, including the regulation of dopamine release (Cachope et al., 2012; Threlfell et al., 2012), corticostriatal plasticity (Augustin et al., 2018; Deffains and Bergman, 2015; Wang et al., 2006), and SPN function (Ding et al., 2010; Goldberg et al., 2012). Despite the challenges in detecting D2Rs in sparse CINs using histochemical or biochemical methods, single-cell RT-PCR has provided less ambiguous evidence of D2Rs in CINs (Yan et al., 1997). Pharmacological studies in vivo and in vitro have supported roles for D2Rs in CIN function. In vivo microdialysis in awake rats showed that D2R activation reduces striatal ACh efflux (DeBoer and Abercrombie, 1996). Subsequent electrophysiological work in ex vivo slices implicated a fast-onset D2R-mediated reduction in embrane currents involved in the spontaneous, tonic firing of CINs (Deng et al., 2007; Maurice et al., 2004; Yan et al., 1997). The D2R agonist-induced effect on baseline firing frequency (Deng et al., 2007; Maurice et al., 2004) is not always observed (Pisani et al., 2006).

Dopamine neurons

D2Rs are also expressed robustly in VTA and SNc DA neurons, where they can be found in somatodendritic compartments but also in axonal terminals densely innervating the striatum (Sesack et al., 1994). D2Rs in DA neurons function as “autoreceptors” and their activation typically reduces DA neuron firing as well as DA synthesis, release, and re-uptake (Schmitz et al., 2002). Subcellular localization of D2Rs appears to be a key determinant in the downstream signaling engaged by the receptor. At or near cell bodies of DA neurons, D2R activation enhances K+ conductances, such as that mediated by G-protein inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs), to reduce cell firing (Lacey et al., 1987; Uchida et al., 2000). In contrast, D2R signaling in DA neuron terminals that contact striatum has been suggested to engage other ion channels, such as Ca2+ and Kv1.2 channels, to inhibit DA release (Martel et al., 2011; Phillips and Stamford, 2000).

Alternative splicing of D2R gene leads to generation of two splice variants, a long isoform (D2L) and a short isoform (D2S) which differ by a 29-amino acid insert in the third cytoplasmic loop of D2L (Dal Toso et al., 1989; Giros et al., 1989; Monsma et al., 1989). Because control of DA synthesis and release was spared following deletion of the D2L isoform, D2S was speculated to be the predominant DA autoreceptor, while the D2L was assumed to be primarily postsynaptic (Lindgren et al., 2003; Usiello et al., 2000). However, both isoforms can be found in SPNs and DA neurons (Radl et al., 2018). In fact, viral restoration of D2L and D2S in a D2R knockout (D2KO) mouse indicated that either of the D2R variants can act as postsynaptic receptors or autoreceptors (Neve et al., 2013).

Cortical neurons

In line with reported effects of dopaminergic agents on cortical-related behaviors (Arnsten et al., 1995; Druzin et al., 2000), it was apparent that cerebral cortical regions were a target of dopamine afferents and expressed D2R mRNA (Gaspar et al., 1995; Weiner et al., 1991). Histological analysis of GFP expression in Drd2-GFP BAC transgenic mice revealed a high degree of colocalization (~95%) with pyramidal neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)(Zhang et al., 2010), suggesting that nearly all pyramidal neurons express D2Rs. A recent cortex-wide characterization of D2R expression in adult mice using genetically-targeted translational profiling uncovered the presence of D2Rs in previously uncharacterized neuronal clusters in limbic and sensory cortical regions (Khlghatyan et al., 2018).Supporting a functional role of D2R in mPFC neurons, multiple groups have reported alterations in pyramidal neuron function at the soma or in corticostriatal terminals in response to quinpirole, a D2R agonist (Bamford et al., 2004; Gee et al., 2012; Tseng and O’Donnell, 2004).

Cortical pyramidal neurons provide a major source of excitatory input to the striatum. Therefore, DA actions on D2Rs within cortical regions may indirectly affect striatal neuron function. Even though histochemical analysis has revealed that only a small fraction of glutamatergic terminals innervating striatum express D2Rs (Wang and Pickel, 2002), local activation of D2Rs significantly reduces corticostriatal transmission (Bamford et al., 2004). Thus, by acting on both pre- and postsynaptic cortical D2Rs, DA may potentially regulate activation of striatal neurons under different behavioral conditions.

Associations between striatal D2Rs and disease

Various disorders that are known to involve dysfunction of the dopamine system also exhibit D2R alterations in striatum. In some cases, D2R involvement has been inferred from the ability of D2R-based drugs to successfully treat disease symptoms or to generate side effects (Seeman, 2002). Other studies have compared changes in the binding of D2R-selective radioligands in striatum of patients to healthy controls (Laruelle, 1998; Volkow et al., 2009). While the uncovered associations cannot establish causation, they have set the stage for the interrogation of D2R function and expression levels as potential contributors to disease etiology.

Schizophrenia

Typical antipsychotics, which primarily target D2Rs, are effective in treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, contributing to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia (Snyder, 1976). With prolonged exposure, antipsychotics, particularly first-generation ones like haloperidol, result in extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), whose incidence has been associated with the degree of occupancy as well as sensitivity of D2Rs (Jarskog et al., 2007; Seeman, 2002). Post-mortem tissue analyses using radioactive D2R ligand binding have predominantly shown increased striatal D2R density in schizophrenia patients, yet the interpretation has been complicated by previous history of neuroleptic treatment or by the variable quality of the samples (Kornhuber et al., 1990). Brain imaging studies in patients have provided more consistent evidence linking D2R alterations and schizophrenia (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). Positron emission tomography (PET) studies, which can measure the baseline binding potential of selective D2R radioligands within the brain, have been used to examine striatal D2R availability in neuropsychiatric disorders. An increase in the density and occupancy of the D2R in the striatum (particularly in dorsal, associative areas) has been frequently reported in patients with schizophrenia, regardless of neuroleptic treatment history (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000; Laruelle, 1998; Wong et al., 1986).

Substance abuse

PET imaging work in the context of chronic substance abuse has consistently shown a reduction of D2R availability in the striatum, including the ventral striatum and NAc. As reviewed previously (Volkow et al., 2009), D2R alterations have been observed in abusers of cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin and alcohol even after months of withdrawal. These alterations appear to have important implications for the long-term outcome of the disorder. For example, in alcoholics, low D2R binding predicts increased alcohol craving, which correlates with a greater susceptibility to relapse (Heinz et al., 2005). In contrast, unaffected members of alcoholic families show higher striatal D2R binding (Volkow et al., 2006), suggesting that D2R function may be protective against alcohol dependence.

PET imaging studies of non-human primates self-administering cocaine have supported the notion that lower striatal D2R availability predicts higher drug intake (Morgan et al., 2002; Nader et al., 2006), but have also shown that chronic cocaine self-administration further lowers D2R availability (Nader et al., 2006). This raises the possibility that reduced D2R availability could also be an outcome of extended drug taking.

Studies in rodents have linked premorbid D2R alterations in the NAc to the vulnerability to seek drugs. For instance, lower NAc D2R availability is associated with higher subsequent cocaine self-administration in rats that show impulsivity as a behavioral trait (Dalley et al., 2007). Further, rats that have been genetically selected for high alcohol preference and consumption show diminished NAc D2R density prior to exposure to alcohol (McBride et al., 1993; Stefanini et al., 1992). Suggesting that differences at the gene expression level might be involved, Bice et al (Bice et al., 2008) found significantly less D2R mRNA in the NAc of high alcohol-preferring mice compared to low-alcohol preferring mice.

Obesity

Excessive and compulsive eating, a primary cause of obesity, may originate from dysregulation of reward-related mechanisms, and shares behavioral and neurobiological features with compulsive drug seeking (Berridge et al., 2010). Like in addiction, imaging studies have demonstrated D2R availability is generally lower in the striatum of obese individuals compared to lean controls (Kenny et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2009), but this not always the case (Karlsson et al., 2015). Recent findings also suggest regional-specific alterations, with body mass index being positively correlated with D2R availability in dorsal and lateral striatum, while being negatively correlated with D2R availability in the ventromedial striatum (Guo et al., 2014). Further, the TaqIA A1 polymorphism, which has been linked to reduced striatal D2Rs, is prevalent in adult obese individuals (Kenny et al., 2013). This relationship has been challenged in a large prospective study in children ages 7–11 years of age (Hardman et al., 2013). However, examination of striatal D2R protein levels in obese rats with extended access to high-calorie, fat-rich food revealed a significant reduction in the highly glycosylated form the D2R, suggesting potential regulation at the post-translational level (Johnson and Kenny, 2010).

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD is typically characterized by inattention, impulsivity, hyperactivity, but also features emotional dysregulation and deficits in reward and motivation (Gallo and Posner, 2016). An initial PET study revealed no differences in [11C] raclopride binding potential in the striatum of teens with ADHD, but the study used considerably older subjects as controls (mean age: 30 years)(Jucaite et al., 2005). However, significantly lower measures of D2R availability have been observed in the left caudate, the NAc and midbrain regions in adult ADHD participants (Volkow et al., 2007; Volkow et al., 2011). Whereas D2R availability was not correlated with classical ADHD symptoms (Volkow et al., 2007), lower scores on a surrogate measure of trait motivation for ADHD participants were significantly correlated with receptor availability in ADHD but not control participants (Volkow et al., 2011). The authors suggested that alterations in D2R levels may contribute to the motivational dysfunction seen in ADHD (Volkow et al., 2011).

Parkinson’s disease (PD)

With the progressive loss of substantia nigra pars compacta DA neurons that is a hallmark of Parkinson disease, the diminished DA in striatum results in decreased activation of postsynaptic D1Rs and D2Rs on direct and indirect pathway SPNs (Albin et al., 1989). This leads to disinhibition of nigral neurons and to the classical symptoms of PD, which include bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor. A potentially compensatory increase in D2R binding has been reported with PET imaging in the caudate of early-stage PD patients, whereas reductions have been observed as the disease progresses, and following treatment with the dopamine precursor L-DOPA (Niccolini et al., 2014). Suggesting a role for D2Rs in PD symptomatology, D2R agonists are often prescribed alone, or in combination with L-DOPA, to ameliorate Parkinsonian symptoms (Kreitzer, 2009).

Establishing causality with regional and cellular specificity

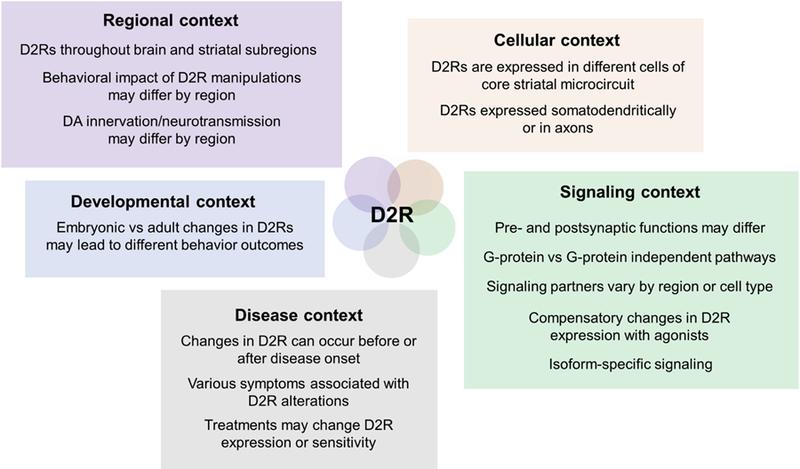

Given the complex regulation, expression patterns and distribution of D2Rs across —and even within— different striatal cells, it is difficult to reconcile the heterogeneity of symptoms in these and other disorders with simple bidirectional changes in D2R binding potential or gene expression in striatum (Figure 1). Many other questions remain in the way of clarifying the role of D2R in striatal function and dysfunction. What specific symptom domains are most closely tied to D2R alterations? Are the changes premorbid or do they result from a lifetime of the disorder? Are there critical developmental windows in which D2R alterations could result in long-term adaptations or impairments? In which cell(s) do the disease-relevant changes in D2R function occur? Have D2Rs in sparse neuronal populations been overlooked with traditional methods? What are the underlying cellular and circuit mechanisms by which D2Rs alter striatal function, and how specific are the alterations to certain disorders? How do D2R drugs work? Can some D2R drug side effects be explained by off-target actions on striatal D2Rs? Could superior D2R-based therapeutics be developed that account for regional, cellular, and intracellular diversity?

Figure 1. Disentangling the roles of D2R in striatum.

Schematic illustrating different challenges that have complicated the investigation of D2Rs. Unlike more global approaches, experimental strategies tailored to the appropriate context and directed to specific cell populations should be better positioned to interrogate the role of D2Rs in health and disease.

Realizing the limitations of correlational research in deciphering how D2R contribute to striatal function in health and disease states, the field has relied on animals to test causal relationships through pharmacology and genetics. Yet even these approaches have encountered critical hurdles related to the widespread expression of D2Rs in brain and the periphery, but also within striatal neurons and their afferents. Nonetheless, many studies have successfully examined causal links between D2R function and striatal physiology, behaviors, and disease models. While there are many impactful studies and research areas that deserve our attention, I will primarily highlight representative studies that 1) showcase how the interrogation of D2R function is becoming progressively more sophisticated, 2) involve specific behavioral sub-components altered in disease, 3) and/or link D2Rs to anatomical or functional changes to the circuitry.

D2R mechanisms in locomotion and incentive motivation

One of the most overt consequences following D2R manipulations in rodents is the impact on locomotor activity. Pharmacological work showed early on that systemic administration of D2/D3 agonist quinpirole in rats would lead to a characteristic biphasic locomotor response, in the absence of concurrent stimulation of D1Rs (Eilam and Szechtman, 1989). Quinpirole caused an initial reduction in locomotion followed by sustained hyperactivity. The effect was also dose-dependent, with the lowest dose decreasing and the higher doses increasing locomotion (Eilam and Szechtman, 1989). The onset of the decrease in activity produced by the low dose occurred within minutes of injection, whereas the hyperactivity was seen about 60–80 min after injection and was persistent (Eilam and Szechtman, 1989). It has been assumed that the hypolocomotor effect stems from activation of higher affinity presynaptic D2R autoreceptors, whereas the hyperactivity is due to the activation of less sensitive D2Rs on SPNs of the indirect pathway (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011). In a sub-regional analysis, quinpirole injections directly into the NAc had locomotor-suppressing effects (Mogenson and Wu, 1991), while a different study showed that blocking D2R reduces locomotion (Baldo et al., 2002). These apparent contradictions highlight the importance of the site of action on behavior.

The cloning of the Drd2 gene precipitated the generation of D2KO mice. Two different D2KO lines initially reported profound reductions in locomotor activity in line with some pharmacological blockade studies (Baik et al., 1995; Jung et al., 1999). These findings were paralleled by the hypolocomotor phenotype in one D2L−/− mouse line (Wang et al., 2000), an effect not seen in a different line (Radl et al., 2018; Usiello et al., 2000). Similarly, the D2S −/− mouse shows no alterations in spontaneous locomotion (Radl et al., 2018). It is possible that, at least in some cases, the remaining D2R isoform can compensate for the loss of the other isoform (Radl et al., 2018).

Recent work has taken advantage of Cre-recombinase-based conditional strategies either in transgenic mice or using viral-mediated gene delivery to disentangle the locomotor effects of D2Rs expressed by specific neuronal populations that converge in striatum. To directly address the contributions of D2R in dopamine neurons, Bello et al (Bello et al., 2011) designed a double-transgenic mouse line (AutoD2RKO) from a cross between Drd2loxP/loxP and Dat+/IRES−cre mice, effectively deleting the Drd2 gene specifically in neurons that express the dopamine transporter (DAT). Importantly, there was no measurable effect on D2R levels in other regions including striatum, either by radioligand autoradiography or in situ hybridization. Consistent with the autoreceptor function of D2Rs in dopamine neurons, AutoD2RKO mice showed severely impaired endogenous DA-mediated inhibitory regulation of DA neuron firing, as well as increased dopamine release and synthesis (Bello et al., 2011). Moreover, while these mice showed no overt physical abnormalities, they were found to be hyperactive in an open field arena. The contrast between these findings and the decreased locomotor phenotype seen in the full D2KO underscore the unique role of D2R autoreceptors in locomotion.

While deletion of D2Rs in CINs did not alter spontaneous locomotion as shown using a CIN-specific D2KO mouse, it altered the locomotor response to D1R and D2R agonists (Kharkwal et al., 2016). D2R deletion in CINs also remarkably eliminated cataleptic behavior induced by the D2R antagonist haloperidol, suggesting a central role for D2Rs in CINs in this Parkinson-like motor side effect of antipsychotics (Kharkwal et al., 2016). Because CINs lacking D2Rs are rendered insensitive to haloperidol in this mouse model, they presumably lead to increased activation of M1 receptors on D2-SPNs, in turn increasing indirect pathway excitability (Kharkwal et al., 2016).

At the cellular level, in line with previous pharmacological evidence (Wang et al., 2006), D2R deletion in these neurons blocks the induction of long-term depression (LTD) on dorsal striatal D1- and D2-SPNs, potentially via increased M1 activation (Augustin et al., 2018). These findings affirmed CINs as a key cellular locus for the well-known D2R involvement in LTD. Moreover, they represent a powerful example of how one set of striatal D2Rs may influence plasticity in a larger circuit involving multiple cellular players. CINs strongly regulate DA release locally from dopaminergic terminals (Cachope et al., 2012; Threlfell et al., 2012), an effect that may involve region-specific roles for CIN D2Rs (Shin et al., 2017). In addition, dorsal striatal CINs lacking D2Rs do not show the characteristic pause in tonic firing following intrastriatal electrical stimulation or dopamine uncaging (Augustin et al., 2018; Kharkwal et al., 2016). Further work will be needed to assess the behavioral impact of lacking this brief pause in dorsal striatal CINs.

The CIN pause, which occurs in vivo in response to salient or reward-related stimuli, is presumed to be important for learned associations of stimuli with motivationally-relevant outcomes (Aosaki et al., 1994a; Aosaki et al., 1994b; Apicella et al., 1991). Dopaminergic lesions as well as systemic haloperidol have been shown to block the pause in vivo (Aosaki et al., 1994a), suggesting that dopamine actions via D2Rs are involved. The underlying cellular mechanisms across striatal sub-regions are not fully understood but have been subject of intense investigation (Chuhma et al., 2014; Deng et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2010; Maurice et al., 2004; Straub et al., 2014).

Complementary up- and down-regulation studies also support a key role for D2Rs in D2-SPNs in locomotion (Dobbs et al., 2016; Donthamsetti et al., 2018; Gallo et al., 2015; Lemos et al., 2016). Targeting of specific neuronal populations through conditional viral vectors was used to upregulate D2R expression (~ 3-fold) in D2-SPNs of the NAc (Gallo et al., 2018; Gallo et al., 2015). Adult Drd2-Cre mice were injected bilaterally in the NAc with a Cre recombinase-dependent adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing the Drd2 gene, leading to stable and selective expression in D2-SPNs. Compared to mice expressing GFP, mice that overexpressed D2R in D2-SPNs showed a significant increase in measures of locomotor activity and exploratory-like behavior in an open field (Gallo et al., 2015). Besides suggesting that D2Rs in D2-SPNs are involved in this behavior, this viral approach also provided additional information on the regional (NAc core) and temporal context (adulthood). These findings offered refined evidence for a D2R contribution to locomotion when acting in NAc, supporting previous pharmacological work linking D2Rs in this region to motor function (Baldo et al., 2002; Canales and Iversen, 2000).

Taking advantage of the selective expression of adenosine 2A receptors (A2ARs) in D2-SPNs, a different study used a transgenic mouse approach to delete D2Rs from D2-SPNs (Lemos et al., 2016). Recapitulating some of the locomotor impairments seen in the global D2KO, as well as in Parkinson disease models, the resulting D2-SPN-specific KO (>80% reduction in Drd2 mRNA) as well as the heterozygous KO (~40% reduction) exhibited a similar reduction in home cage activity (Lemos et al., 2016). In addition, a gene-dependent decrease in distance traveled in an open field and in the rotarod task, which tests motor skill learning. While this mouse model is highly selective for D2-SPNs, it lacks the spatiotemporal control over D2R expression that is afforded by viral strategies. To ameliorate this issue, the study further showed that viral-mediated D2R knockdown in the NAc, albeit non-cell selectively, was sufficient to reduce locomotion (Lemos et al., 2016). The study also provided mechanistic evidence suggesting that the impact of D2R deletion on locomotion was mediated by enhanced inhibitory transmission from D2-SPNs, without alterations in DA transmission (Lemos et al., 2016).

Together these different genetically targeted approaches provide strong support for an involvement of D2R in ventral and dorsal striatal D2-SPNs, but not CINs, in motor control. Moreover, they are consistent with an inhibitory role of D2R on GABA output from D2-SPNs (Cooper and Stanford, 2001; Dobbs et al., 2016; Gallo et al., 2018; Kohnomi et al., 2012).

In other less cell-selective manipulations of D2R expression, there was little to no impact on basal locomotion (Kellendonk et al., 2006; Trifilieff et al., 2013). To model the increase in striatal D2R occupancy seen in schizophrenia patients, Kellendonk et al (Kellendonk et al., 2006) generated a mouse line that selectively overexpressed D2Rs in SPNs, beginning in embryonic stages (D2R-OE). Besides the spatially restricted overexpression, one major advantage of this approach was that transgene expression was under control of an inducible promoter system that could be switched off (Kellendonk et al., 2006). Achieving an overexpression of approximately 15%, D2R-OE mice showed deficits in cognitive tasks and in tasks measuring motivation, modeling important schizophrenia endophenotypes (Kellendonk et al., 2006). Turning off the transgene in adulthood normalized striatal D2R levels, reversing the motivational deficits but not the cognitive deficits (Kellendonk et al., 2006). These findings suggested that increased D2R expression early in development was sufficient to induce cognitive impairment later in life. They also indicated that ongoing D2R overexpression in adulthood contributes to the motivational deficits.

Overexpression of D2Rs in D2R-OE mice led to profound functional and neuroanatomical changes within, but also outside the striatum. In one example of distal adaptations, D2R upregulation in striatum led to deficits in inhibitory transmission and dopamine sensitivity in mPFC (Li et al., 2011). In striatum, whole-cell patch clamp recordings revealed that both D2 and D1-SPNs were hyperexcitable, and showed decreased dendritic arbor length and complexity, effects that were linked to changes in gene expression (Cazorla et al., 2012). Furthermore, D2R-OE mice displayed increased density of the D1-SPN axon collaterals to the globus pallidus (GPe), without alterations in the density of axonal terminals in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (Cazorla et al., 2014). These “bridging collaterals” that provide D1-SPN inhibition of indirect pathway target nuclei were remarkably plastic. When the transgene was turned off, the bridging collaterals density returned to control levels, an effect that was recapitulated by treatment with haloperidol (Cazorla et al., 2014). Moreover, reducing D2R expression (D2KO) or blocking D2R function in wildtype mice with haloperidol was capable of further reducing bridging collateral density (Cazorla et al., 2014). The authors demonstrated that GPe firing activity in vivo was significantly reduced in D2R-OE mice by optogenetic stimulation of dorsal striatal D1-SPNs. Furthermore, this stimulation increased locomotion in control mice, but led to decreased locomotion in the D2R-OE mice (Cazorla et al., 2014). These results suggest that striatal D2Rs can re-shape the neuronal architecture and alter the functional balance of striatal output pathways. They further raise the possibility that D1-SPN collateralization to GPe could be increased in schizophrenia and that treatment with antipsychotics may reduce this neuroadaptation (Cazorla et al., 2014).

While the D2R-OE model enabled D2R upregulation from early in development, the consequences of adult D2R upregulation remained unclear. Moreover, given that the expression of D2R transgene was found in dorsal and ventral striatal regions, it was unclear whether there was a regional-specific contribution of D2R upregulation to behavior. A subsequent study compared the effects of D2R upregulation in either the caudate putamen (CPu) or the NAc on incentive motivation using viral overexpression approach (Trifilieff et al., 2013). Adult D2R upregulation in NAc, but not in the CPu, led to a specific increase in the animal’s willingness to work for food (Trifilieff et al., 2013). The findings were consistent with brain imaging studies linking reductions in ventral striatal D2R availability in disorders that feature motivation dysfunction, but also with pharmacological work showing reductions in motivated behavior when D2R function is disrupted (Salamone et al., 2015). Besides the differences in regional specificity, the opposite effects on motivation seen in this model and in the D2R-OE model were attributed to differences in the developmental onset and degree of overexpression (Trifilieff et al., 2013). In addition, the viral expression reported by Trifilieff et al, though region-specific, was presumably less restricted to SPNs (Trifilieff et al., 2013).

Given that D2R expression is enriched in D2-SPNs relative to D1-SPNs, and is also present in CINs, a more cell-selective approach was required to begin to disentangle the neurobiological underpinnings of D2R involvement in motivation. To this end, a conditional viral strategy in the Drd2-Cre line was used to upregulate D2R expression selectively in D2-SPNs in adult NAc (Gallo et al., 2018). It was shown that D2R upregulation in D2-SPNs is sufficient to increase performance in several tasks measuring incentive motivation (Gallo et al., 2018). This behavioral effect was associated with a reduction in the inhibitory transmission to two known targets of D2-SPNs: D1-SPNs and ventral pallidum (VP) neurons, as shown by reduced inhibitory currents triggered by optogenetic stimulation of D2-SPNs in ex vivo brain slices (Gallo et al., 2018). However, in vivo, while global D1-SPN activity was not altered by D2R upregulation, VP neuron activity was significantly disinhibited (Gallo et al., 2018). Furthermore, the findings showed that chemogenetic inhibition of D2-SPN terminals in VP was sufficient to achieve the behavioral phenotype, leading to the hypothesis that additional presynaptic D2Rs increase motivation by blunting inhibitory transmission to VP and thus weaken indirect pathway output. Thus, it is possible that therapeutic strategies that selectively attenuate indirect pathway function may lead to more precise and effective treatments of motivational dysfunction (Nunes et al., 2013).

The role of D2Rs in CINs in motivation for natural rewards was only recently explored using genetically-targeted approaches (Gallo et al., 2018). D2R overexpression in the NAc of ChAT-Cre mice did not alter performance on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, in contrast to the robust phenotype seen following D2R upregulation in D2-MSNs (Gallo et al., 2018) or after loss of D2R in dopamine neurons (Bello et al., 2011; de Jong et al., 2015). It is possible that a role for CIN D2Rs will be revealed in other tasks assessing motivated behaviors, particularly those that involve incentive cues. In addition, given the documented heterogeneity of CIN responses to dopamine across striatal sub-regions (Chuhma et al., 2014), it remains to be seen whether manipulating CIN D2R expression elsewhere in striatum can impact performance in PR or other tasks of motivation.

D2R mechanisms in addictive behaviors

In addition to their involvement in the pursuit of natural reward, D2Rs have been shown to be critical for drug liking and drug-seeking behaviors. Early work using the D2R antagonist pimozide linked D2R to cocaine reinforcement in rats (De Wit and Wise, 1977), and since, numerous studies have used pharmacological approaches to address the role of D2R in different models of addictive behavior (Self, 2004). For example, systemic administration of different D2R antagonists suppressed cocaine-induced locomotion (Chausmer and Katz, 2001). Cocaine conditioned place preference (CPP), which measures the rewarding properties of a drug, was attenuated by D2R blockade with haloperidol (Spyraki et al., 1987) but not sulpiride (Cervo and Samanin, 1995). Intra-accumbens delivery of sulpiride attenuated cocaine-induced locomotion, but had no effect on cocaine CPP (Baker et al., 1996). More recently, evidence from D2KO mice has revealed impairments in cocaine-induced locomotor activity, supporting pharmacological studies (Chausmer et al., 2002; Welter et al., 2007). These mice have also been shown to self-administer cocaine, yet do so at higher rates than controls when high cocaine doses are used (Caine et al., 2002). On the other hand, adenovirus-mediated, non-cell selective D2R overexpression in the NAc transiently decreased cocaine self-administration in rats (Thanos et al., 2008). While most studies appear to attribute a permissive role to D2Rs in cocaine-related locomotion, it is possible that D2R involvement in drug-seeking is more nuanced, depending on cocaine levels as well as on the degree of D2R expression.

The cellular context of D2R expression may also have a unique impact on cocaine reward. For example, compared to controls, AutoD2RKO mice exhibited increased sensitivity to the locomotor effects and the rewarding properties of a low dose of cocaine (Bello et al., 2011) and showed enhanced reactivity to cocaine-paired cues (Holroyd et al., 2015). These behaviors were associated with a loss of inhibition over phasic DA release and over DA synthesis, consistent with autoreceptor function (Bello et al., 2011; Holroyd et al., 2015). Subsequent work in rats using viral-mediated knockdown of D2R expression in VTA attempted to determine whether D2Rs of VTA could account for the cocaine hypersensitivity seen in the absence of D2R in all DA neurons (de Jong et al., 2015). VTA D2R knockdown increased the locomotor stimulating effects of a low dose of cocaine and increased the motivation to respond for sucrose or cocaine in a PR task, but did not affect other aspects of addictive behavior, such as compulsivity and reinstatement (de Jong et al., 2015). Although direct comparisons of the two rodent models are hindered by the different methodology used (Bello et al., 2011; de Jong et al., 2015; Holroyd et al., 2015), the findings generally support an involvement of midbrain D2 autoreceptors in the mechanisms of cocaine reward.

Recent work in the D2-SPN-specific D2KO mouse has shown that D2Rs in D2-SPNs are necessary for acute cocaine-induced locomotion (Dobbs et al., 2016). In addition, this study shed new light on potential circuit mechanisms underlying the role of D2R on cocaine-induced motor behavior. The authors showed that the D2R agonist quinpirole or cocaine could reliably attenuate the inhibitory collateral transmission from D2-SPNs to D1-SPNs triggered by optogenetic stimulation of D2-SPNs (Dobbs et al., 2016). However, the quinpirole- or cocaine-mediated disinhibition of D1-SPNs was absent in the D2-SPN-specific D2KO. Moreover, chemogenetic inhibition of D2-SPNs in NAc reversed the diminished acute cocaine locomotor response seen in D2-SPN specific D2KO mice, indicating that enhanced Gi signaling in D2-SPNs is sufficient for the locomotor stimulating effects of the drug (Dobbs et al., 2016). These findings imply that D2Rs, possibly through Gi signaling, play a key role in regulating inhibitory output to D1-SPNs to mediate cocaine-induced locomotion. VP neuron inhibition appeared to be less affected by quinpirole than in D1-SPNs, and given the less dense dopaminergic innervation in VP compared to NAc, it was suggested that elevated dopamine levels triggered by cocaine acutely stimulate locomotion primarily by activating D2-SPN D2Rs to disinhibit D1-SPNs (Dobbs et al., 2016). While the absence of D2Rs in the predominant D2R-expressing cell population of the NAc did not affect behavioral sensitization or place preference to cocaine, it would be interesting to see whether cocaine self-administration is altered in these mice.

Accumulating in vivo evidence from genetic mouse models has implicated D2R-mediated recruitment of G-protein independent β-arrestin signaling in the locomotor response to psychostimulants (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Beaulieu et al., 2007; Donthamsetti et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2018). D2KO mice and β-arrestin-2 KO mice, not only show impaired amphetamine-induced locomotion, which is mediated by Akt-GSK-3 signaling, but also show diminished engagement of these downstream effectors (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Beaulieu et al., 2004; Beaulieu et al., 2007). Given its ubiquitous expression in many cell types and its interactions with various GPCRs, interpreting the behavioral effects of global deletion of β-arrestin warrant caution. Yet, more recent work has helped to ease this concern by directly testing the effect of expressing D2Rs that are biased towards β-arrestin-signaling (Donthamsetti et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2018). Targeting expression of a β-arrestin-biased D2R mutant into the D2-SPNs of a D2-SPN-specific D2KO was sufficient to partially rescue basal locomotion, as well as the motor response to psychostimulants as compared to restoration of a wild-type D2R (Rose et al., 2018). The study also showed that a G-protein biased mutant D2R also partially rescues these phenotypes, suggesting a functional convergence of D2R-mediated G-protein dependent and independent pathways. However, the β-arrestin-biased D2R mutant was shown to be only partially biased toward arrestin recruitment, leaving open the possibility that the enhanced D2R-mediated locomotor effect could be due to β-arrestin or the remaining G protein signaling or a combination of both (Donthamsetti et al., 2018; Peterson et al., 2015). Indeed, expression of a more biased β-arrestin D2R mutant in NAc D2-SPNs reversed blunted locomotion in D2KO mice, both under basal conditions and following acute cocaine administration (Donthamsetti et al., 2018). These results suggest that D2R-mediated β-arrestin recruitment is sufficient to rescue hypolocomotion, in the apparent absence of D2R-mediated G protein signaling. Remarkably, overexpression of this β-arrestin biased D2R in NAc D2-SPNs did not increase motivation (Donthamsetti et al., 2018), contrary to the outcome of wild-type D2R overexpression (Donthamsetti et al., 2018; Gallo et al., 2018). This study raised the interesting possibility of a dissociation between the D2R signaling mechanisms underlying locomotor activity and motivated behavior. Additional research remains to be done to elucidate the cellular and circuit mechanisms underlying the unique β-arrestin and G-protein-mediated contributions to these and other behaviors.

PET imaging studies in chronic alcohol abusers have revealed reductions in D2R binding potential in striatum, including ventral striatum, and have raised the possibility that increased D2R function could protect against excessive alcohol consumption and dependence (Martinez et al., 2005; Volkow et al., 2006; Volkow et al., 1996). A number of pharmacological studies using D2R agonists/antagonists in rodents or using D2R knockout mice are consistent with this notion (Bulwa et al., 2011; Hodge et al., 1997; Levy et al., 1991; Ng and George, 1994), while other studies propose that D2Rs are necessary for the alcohol-related behaviors (Hodge et al., 1997; Phillips et al., 1998; Rassnick et al., 1992; Samson et al., 1993). These inconsistencies likely result from differences in the specific alcohol drinking models and dopamine agonist/antagonist doses or routes of administration (eg. NAc vs. systemic).

Thanos et al have also demonstrated that rats and mice previously trained to self-administer alcohol reduce their consumption and preference for alcohol following D2R overexpression in adult NAc (Thanos et al., 2005; Thanos et al., 2001). This protective effect appears to depend on the existing endogenous levels of D2Rs. For instance, D2KO mice, which already showed reduced alcohol consumption relative to wildtype mice, exhibit a brief increase in alcohol intake following D2R overexpression in NAc (Thanos et al., 2005). Nonetheless, these results have important implications for understanding the role of D2Rs in alcoholism, as they demonstrated that D2R overexpression in a specific striatal region can have direct consequences on pre-established alcohol intake. However, it remained to be addressed whether increasing D2R in drug-naïve animals could also confer protection against future alcohol consumption. And if this were the case, which neuronal population(s) could be responsible?

These issues were addressed using a conditional AAV vector to overexpress D2Rs in NAc core D2-SPNs (Gallo et al., 2015). While associated with increased locomotor activity and generalized fluid consumption, D2R upregulation in alcohol-naïve mice did not reduce subsequent dependence-like escalation of alcohol intake, nor did it favor de-escalation of alcohol drinking by pairing alcohol with aversive outcomes (Gallo et al., 2015). These data argued that increased accumbal D2-SPN D2R levels do not diminish susceptibility to future alcohol consumption, and were at odds with the protective effect of D2R upregulation once self-administration had been established (Thanos et al., 2001). A protective action may require D2R overexpression in other D2R-expressing cells of NAc core or in D2-SPN in other striatal regions, such as the NAc shell or the dorsal striatum. Future systematic analysis of the contribution of D2Rs in each of these regions and neuron types to alcohol drinking may help reconcile the brain imaging literature with the preclinical work.

D2R mechanisms in obesity

Prolonged access to high fat cafeteria diets resulted in compulsive-like eating and excessive adiposity, as well as in reduced D2R expression in striatum in rats (Johnson and Kenny, 2010). Using a lentiviral vector to deliver a short hairpin interfering RNA (shRNA) that knocked down D2R expression (~40–50%) in striatal neurons of the dorsolateral striatum, this study reported an accelerated emergence of compulsive-like food intake compared to controls (Johnson and Kenny, 2010). Because this effect was specific to animals fed cafeteria diets, and not observed in animals fed standard diets, it was implied that D2R alterations contribute to the blunting of reward sensitivity elicited by chronic access to obesogenic food (Kenny et al., 2013). In contrast, global D2R knockdown (D2KD) achieved in a transgenic mouse line did not alter the rates of diet-induced obesity (DIO) (Beeler et al., 2016). However, this study demonstrated that while wildtype mice with access to voluntary physical activity gained less weight from obesogenic diets, D2KD mice did not benefit from such voluntary exercise opportunities (Beeler et al., 2016). Despite the different approaches used to downregulate D2Rs, these studies (Beeler et al., 2016; Johnson and Kenny, 2010) suggest that D2R alterations may be implicated in both reward and physical activity adaptations that increase vulnerability to obesity.

Disentangling these behavioral outcomes is likely to require cell-type specific strategies. D2-SPN-specific KO mice, for example, are similarly vulnerable to DIO as wildtype mice (Friend et al., 2017). Yet, these mice show impaired locomotor activity, like obese mice, which show reduced striatal D2R binding and reduced physical activity (Friend et al., 2017). Together these findings suggest that lower striatal D2R levels in D2-SPNs may not necessarily predispose mice to obesity. In contrast, overexpression of D2Rs in D2-SPNs of the NAc core, which increases open field activity, is associated with decreased body weight (Gallo et al., 2015). While regional context may explain the different effects on weight control achieved with these two D2-SPN-specific manipulations (entire striatum vs NAc core), further work is required to fully determine whether the impact of ongoing D2R levels in adult D2-SPNs on obesity is preferentially tied to motor regulation. Interestingly, D2R overexpression in SPNs during development leads to robust weight gain and increased adiposity, while altering energy balance, especially with access to a high-fat diet (Labouesse et al., 2018). This phenotype was maintained even when expression of the D2R transgene was turned off in adulthood, suggesting that developmental D2R levels in SPNs are critical determinants of future weight gain (Labouesse et al., 2018).

D2R mechanisms in impulsive behavior

Overeating and weight gain, as well as addictive disorders, may involve deficits in impulse control (Michaud et al., 2017). It is, therefore, not surprising that striatal D2Rs have also been implicated in regulating response inhibition in animal models. PET imaging of D2R availability was performed in rats selectively bred for their trait impulsivity (Dalley et al., 2007). Lower D2R availability was reported in the ventral striatum, but not the dorsolateral striatum, of high-impulsive rats as compared to non-impulsive rats (Dalley et al., 2007). Moreover, D2R availability in the ventral striatum was inversely correlated with impulsive action, as measured by premature responding on the five-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) (Bari et al., 2008; Dalley et al., 2007). Importantly, individual differences in impulsivity measures predicted individual variation in the rate of intravenous cocaine self-administration (Dalley et al., 2007). While these findings do not necessarily impute causality, emerging work using genetically-targeted approaches is beginning to validate the hypothesis that D2Rs are directly involved in impulsive behavior. Using a reversal learning task, a recent study in AutoD2RKO mice reported impaired completion of a sustained nose-poke response, indicating that D2Rs in dopamine neurons are critical for appropriate waiting to obtain reward (Linden et al., 2018).

Beyond affecting impulsive action, D2R alterations could also impair impulsive choice, another component of impulsivity that sometimes refers to decreased tolerance to delays (Michaud et al., 2017). Indeed, AAV-mediated knockdown of D2R in VTA of rats led to the development of a significant preference for smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards (Bernosky-Smith et al., 2018). Given that the impulsivity endophenotype is at the core of several disorders, including addiction, overeating, ADHD, pathological gambling and schizophrenia, continued interrogation of D2R in these and other relevant cell types (i.e. SPNs and CINs) could inform the development of therapeutic interventions that also target inhibitory control (Michaud et al., 2017).

Summary and Conclusions

Since the first demonstration that DA was a neurotransmitter more than 60 years ago, many discoveries have been made that critically link D2Rs to striatal function. In fact, within five years of the cloning of the rat Drd2 gene in 1988 (Bunzow et al., 1988), the annual number of publications involving D2Rs tripled, and has remained steady since. In that time, valuable insights from human brain imaging studies combined with the power of genetics and pharmacology in animal models have cemented the notion that striatal D2Rs are directly involved in shaping the structure and the function of neural circuits to mediate a host of dopamine-related behaviors.

Likewise, technical advances that enable cell-selective targeting of D2R are beginning to offer a clearer view of D2R function in different neuron populations. However, many challenges and exciting new questions remain to be addressed. While D2Rs in SPNs and dopamine neurons have received considerable attention, relatively less is known about D2Rs in cholinergic interneurons and their region-specific contributions to dopamine-dependent behaviors. Moreover, D2Rs in cortical neurons, particularly at corticostriatal synapses, may have important behavioral and therapeutic implications (Cui et al., 2018; Urs et al., 2016), yet they also remain poorly understood.

Current evidence about cell-selective actions of striatal D2Rs stems primarily from D2R deletion throughout striatum or from local D2R overexpression, but the use of cell- and region-specific knockdown approaches in the adult brain has been limited and should be considered. Moreover, methods that afford flexible temporal control of D2R expression throughout the lifespan of an animal (Cazorla et al., 2014; Kellendonk et al., 2006) would be well-suited to probe the developmental consequences of D2R alterations. Adaptations of techniques like optogenetics and chemogenetics to the D2R, as done with a D1R opsin chimera (Gunaydin et al., 2014), could enhance experimental control over D2R activation/inhibition in a cell-targeted fashion. Techniques that enable dissection of somatodendritic vs axonal functions of D2Rs may unveil distinct sub-cellular roles in behavior (Stachniak et al., 2014).

However, one major challenge will be to understand how the diverse actions of D2Rs in multipartite, dopamine-sensitive circuits are coordinated to produce specific behaviors across species. It is possible that emerging techniques for imaging neuronal activity in different neuronal population in behaving animals may illuminate patterns and temporal dynamics of D2R actions in each region (Cui et al., 2013; Gallo et al., 2018; Lemos et al., 2016).

While there are some inconsistencies between PET imaging in brain disorders and preclinical work on D2Rs that must be reconciled, it is likely that D2R alterations may confer vulnerability to developing neuropsychiatric disorders and specific endophenotypes. It is also possible that D2R alterations arise after developing a disorder, as in chronic substance abuse or obesity (Friend et al., 2017). In either case, further work will be needed to understand the factors and cellular mechanisms leading to these alterations (Trifilieff et al., 2017).

Pharmacological interventions aimed at D2Rs have been effective in treating certain symptoms, but not others, and may even cause serious side effects (Wang et al., 2018). New generations of efficacious therapeutics that have minimal side effects will need to consider the widespread expression of D2Rs, as well as the heterogeneity of D2R signaling and function throughout the brain. For example, such efforts will have to account for region-specific differences in the coupling to downstream effectors, such as G proteins (Marcott et al., 2018) and their functional interactions with β-arrestins (Urs et al., 2016). The continued evolution of functionally-selective D2R ligands, aided now by the recent unveiling of the crystal structure of D2R bound by the antipsychotic risperidone (Wang et al., 2018), may offer new hope in this endeavor (Peterson et al., 2015). In striatum, the selective expression of A2ARs in D2-SPNs may be leveraged to design A2AR-based approaches aimed at counteracting the effects of decreased D2R and overactive indirect pathway function (Nunes et al., 2013).

Informed by imaging and pharmacological work, the continued investigation of reliable disease endophenotypes and the use of cell-targeted strategies are well positioned to disentangle the complex roles of D2Rs in striatal function. Such refined information will not only shed light on the brain-wide actions of dopamine but it may also lead to improved treatment outcomes for multifactorial and heterogeneous disorders.

Highlights.

Dopamine D2 receptors mediate many of the functions of dopamine in striatum.

Various disorders feature alterations in striatal D2 receptors.

Their precise role in shaping circuits and behavior are not well understood.

Recent studies have begun to dissect their roles in health and disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding source(s):

This work was supported by NIH MH107648 to E.G.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, Weiss R, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Van Heertum RL, Gorman JM, Laruelle M, 2000. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia.[comment]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, 8104–8109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB, 1989. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends in Neurosciences 12, 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Graybiel AM, Kimura M, 1994a. Effect of the nigrostriatal dopamine system on acquired neural responses in the striatum of behaving monkeys. Science 265, 412–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Tsubokawa H, Ishida A, Watanabe K, Graybiel AM, Kimura M, 1994b. Responses of tonically active neurons in the primate’s striatum undergo systematic changes during behavioral sensorimotor conditioning. Journal of Neuroscience 14, 3969–3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apicella P, Scarnati E, Schultz W, 1991. Tonically discharging neurons of monkey striatum respond to preparatory and rewarding stimuli. Experimental Brain Research 84, 672–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Steere JC, Goldman-Rakic PS, 1995. Dopamine D2 receptor mechanisms contribute to age-related cognitive decline: the effects of quinpirole on memory and motor performance in monkeys. Journal of Neuroscience 15, 3429–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin SM, Chancey JH, Lovinger DM, 2018. Dual Dopaminergic Regulation of Corticostriatal Plasticity by Cholinergic Interneurons and Indirect Pathway Medium Spiny Neurons. Cell Rep 24, 2883–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik J-H, Picetti R, Saiardi A, Thiriet G, Dierich A, Depaulis A, Le Meur M, Borrelli E, 1995. Parkinsonian-like locomotor impairment in mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. Nature 377, 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Khroyan TV, O’Dell LE, Fuchs RA, Neisewander JL, 1996. Differential effects of intra-accumbens sulpiride on cocaine-induced locomotion and conditioned place preference. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 279, 392–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Sadeghian K, Basso AM, Kelley AE, 2002. Effects of selective dopamine D1 or D2 receptor blockade within nucleus accumbens subregions on ingestive behavior and associated motor activity. Behavioural Brain Research 137, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford NS, Zhang H, Schmitz Y, Wu NP, Cepeda C, Levine MS, Schmauss C, Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Sulzer D, 2004. Heterosynaptic dopamine neurotransmission selects sets of corticostriatal terminals. Neuron 42, 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, 2008. The application of the 5-choice serial reaction time task for the assessment of visual attentional processes and impulse control in rats. Nature Protocols 3, 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, 2011. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacological Reviews 63, 182–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, 2005. An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Yao WD, Kockeritz L, Woodgett JR, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, 2004. Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 5099–5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Tirotta E, Sotnikova TD, Masri B, Salahpour A, Gainetdinov RR, Borrelli E, Caron MG, 2007. Regulation of Akt signaling by D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience 27, 881–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RM, 1988. Association of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors with specific cellular elements in the basal ganglia of the cat: the uneven topography of dopamine receptors in the striatum is determined by intrinsic striatal cells, not nigrostriatal axons. Neuroscience 27, 851–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler JA, Faust RP, Turkson S, Ye H, Zhuang X, 2016. Low Dopamine D2 Receptor Increases Vulnerability to Obesity Via Reduced Physical Activity, Not Increased Appetitive Motivation. Biological Psychiatry 79, 887–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello EP, Mateo Y, Gelman DM, Noain D, Shin JH, Low MJ, Alvarez VA, Lovinger DM, Rubinstein M, 2011. Cocaine supersensitivity and enhanced motivation for reward in mice lacking dopamine D2 autoreceptors. Nature Neuroscience 14, 1033–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernosky-Smith KA, Qiu YY, Feja M, Lee YB, Loughlin B, Li JX, Bass CE, 2018. Ventral tegmental area D2 receptor knockdown enhances choice impulsivity in a delay-discounting task in rats. Behavioural Brain Research 341, 129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Ho CY, Richard JM, DiFeliceantonio AG, 2010. The tempted brain eats: pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Research 1350, 43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, Matamales M, Herve D, Valjent E, Girault JA, 2008. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. Journal of Neuroscience 28, 5671–5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bice PJ, Liang T, Zhang L, Strother WN, Carr LG, 2008. Drd2 expression in the high alcohol-preferring and low alcohol-preferring mice. Mammalian Genome 19, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulwa ZB, Sharlin JA, Clark PJ, Bhattacharya TK, Kilby CN, Wang Y, Rhodes JS, 2011. Increased consumption of ethanol and sugar water in mice lacking the dopamine D2 long receptor. Alcohol 45, 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzow JR, Van Tol HH, Grandy DK, Albert P, Salon J, Christie M, Machida CA, Neve KA, Civelli O, 1988. Cloning and expression of a rat D2 dopamine receptor cDNA. Nature 336, 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachope R, Mateo Y, Mathur BN, Irving J, Wang HL, Morales M, Lovinger DM, Cheer JF, 2012. Selective activation of cholinergic interneurons enhances accumbal phasic dopamine release: setting the tone for reward processing. Cell Rep 2, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Patel S, Bristow L, Kulagowski J, Vallone D, Saiardi A, Borrelli E, 2002. Role of dopamine D2-like receptors in cocaine self-administration: studies with D2 receptor mutant mice and novel D2 receptor antagonists. Journal of Neuroscience 22, 2977–2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales JJ, Iversen SD, 2000. Psychomotor-activating effects mediated by dopamine D(2) and D(3) receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 67, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Lindqvist M, Magnusson TOR, 1957. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine and 5- Hydroxytryptophan as Reserpine Antagonists. Nature 180, 1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, de Carvalho FD, Chohan MO, Shegda M, Chuhma N, Rayport S, Ahmari SE, Moore H, Kellendonk C, 2014. Dopamine D2 receptors regulate the anatomical and functional balance of basal ganglia circuitry. Neuron 81, 153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, Shegda M, Ramesh B, Harrison NL, Kellendonk C, 2012. Striatal D2 receptors regulate dendritic morphology of medium spiny neurons via Kir2 channels. Journal of Neuroscience 32, 2398–2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Grande C, Saulle E, Martin AB, Gubellini P, Pavon N, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Moratalla R, Calabresi P, 2003. Distinct roles of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in motor activity and striatal synaptic plasticity. Journal of Neuroscience 23, 8506–8512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Buchwald NA, Levine MS, 1993. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine in the neostriatum are dependent upon the excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes activated. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90, 9576–9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Samanin R, 1995. Effects of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor antagonists on the acquisition and expression of cocaine conditioning place preference. Brain Research 673, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chausmer AL, Elmer GI, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Grandy DK, Katz JL, 2002. Cocaine-induced locomotor activity and cocaine discrimination in dopamine D2 receptor mutant mice. Psychopharmacology 163, 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chausmer AL, Katz JL, 2001. The role of D2-like dopamine receptors in the locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine in mice. Psychopharmacology 155, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuhma N, Mingote S, Moore H, Rayport S, 2014. Dopamine neurons control striatal cholinergic neurons via regionally heterogeneous dopamine and glutamate signaling. Neuron 81, 901–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AJ, Stanford IM, 2001. Dopamine D2 receptor mediated presynaptic inhibition of striatopallidal GABA(A) IPSCs in vitro. Neuropharmacology 41, 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote SR, Chitravanshi VC, Bleickardt C, Sapru HN, Kuzhikandathil EV, 2014. Overexpression of the dopamine D3 receptor in the rat dorsal striatum induces dyskinetic behaviors. Behavioural Brain Research 263, 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, Costa RM, 2013. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature 494, 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Li Q, Geng H, Chen L, Ip NY, Ke Y, Yung WH, 2018. Dopamine receptors mediate strategy abandoning via modulation of a specific prelimbic cortex-nucleus accumbens pathway in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, E4890–e4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Toso R, Sommer B, Ewert M, Herb A, Pritchett DB, Bach A, Shivers BD, Seeburg PH, 1989. The dopamine D2 receptor: Two molecular forms generated by alternative splicing. EMBO Journal 8, 4025–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ESJ, Theobald DEH, Lääne K, Peña Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron J-C, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, 2007. Nucleus Accumbens D2/3 Receptors Predict Trait Impulsivity and Cocaine Reinforcement. Science 315, 1267–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Filloux FM, Wamsley JK, 1988. Evidence for dopamine D-2 receptors on cholinergic interneurons in the rat caudate-putamen. Life Sciences 42, 1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JW, Roelofs TJ, Mol FM, Hillen AE, Meijboom KE, Luijendijk MC, van der Eerden HA, Garner KM, Vanderschuren LJ, Adan RA, 2015. Reducing Ventral Tegmental Dopamine D2 Receptor Expression Selectively Boosts Incentive Motivation. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2085–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H, Wise RA, 1977. Blockade of cocaine reinforcement in rats with the dopamine receptor blocker pimozide, but not with the noradrenergic blockers phentolamine or phenoxybenzamine. Canadian Journal of Psychology 31, 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer P, Abercrombie ED, 1996. Physiological release of striatal acetylcholine in vivo: modulation by D1 and D2 dopamine receptor subtypes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 277, 775–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffains M, Bergman H, 2015. Striatal cholinergic interneurons and cortico-striatal synaptic plasticity in health and disease. Movement Disorders 30, 1014–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Zhang Y, Xu ZC, 2007. Involvement of I(h) in dopamine modulation of tonic firing in striatal cholinergic interneurons. Journal of Neuroscience 27, 3148–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JB, Guzman JN, Peterson JD, Goldberg JA, Surmeier DJ, 2010. Thalamic gating of corticostriatal signaling by cholinergic interneurons. Neuron 67, 294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs LK, Kaplan AR, Lemos JC, Matsui A, Rubinstein M, Alvarez VA, 2016. Dopamine Regulation of Lateral Inhibition between Striatal Neurons Gates the Stimulant Actions of Cocaine. Neuron 90, 1100–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donthamsetti P, Gallo EF, Buck DC, Stahl EL, Zhu Y, Lane JR, Bohn LM, Neve KA, Kellendonk C, Javitch JA, 2018. Arrestin recruitment to dopamine D2 receptor mediates locomotion but not incentive motivation. Molecular Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Druzin MY, Kurzina NP, Malinina EP, Kozlov AP, 2000. The effects of local application of D2 selective dopaminergic drugs into the medial prefrontal cortex of rats in a delayed spatial choice task. Behavioural Brain Research 109, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulawa SC, Grandy DK, Low MJ, Paulus MP, Geyer MA, 1999. Dopamine D4 receptor-knock-out mice exhibit reduced exploration of novel stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience 19, 9550–9556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam D, Szechtman H, 1989. Biphasic effect of D-2 agonist quinpirole on locomotion and movements. European Journal of Pharmacology 161, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floran B, Floran L, Sierra A, Aceves J, 1997. D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of GABA release by endogenous dopamine in the rat globus pallidus. Neuroscience Letters 237, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick AL, Yano H, Trifilieff P, Vishwasrao HD, Biezonski D, Meszaros J, Urizar E, Sibley DR, Kellendonk C, Sonntag KC, Graham DL, Colbran RJ, Stanwood GD, Javitch JA, 2015. Evidence against dopamine D1/D2 receptor heteromers. Molecular Psychiatry 20, 1373–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend DM, Devarakonda K, O’Neal TJ, Skirzewski M, Papazoglou I, Kaplan AR, Liow J-S, Guo J, Rane SG, Rubinstein M, Alvarez VA, Hall KD, Kravitz AV, 2017. Basal Ganglia Dysfunction Contributes to Physical Inactivity in Obesity. Cell Metabolism 25, 312–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarraga E, Hernandez-Lopez S, Reyes A, Barral J, Bargas J, 1997. Dopamine facilitates striatal EPSPs through an L-type Ca2+ conductance. Neuroreport 8, 2183–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo EF, Meszaros J, Sherman JD, Chohan MO, Teboul E, Choi CS, Moore H, Javitch JA, Kellendonk C, 2018. Accumbens dopamine D2 receptors increase motivation by decreasing inhibitory transmission to the ventral pallidum. Nat Commun 9, 1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo EF, Posner J, 2016. Moving towards causality in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: overview of neural and genetic mechanisms. The Lancet Psychiatry 3, 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo EF, Salling MC, Feng B, Moron JA, Harrison NL, Javitch JA, Kellendonk C, 2015. Upregulation of Dopamine D2 Receptors in the Nucleus Accumbens Indirect Pathway Increases Locomotion but Does Not Reduce Alcohol Consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gaspar P, Bloch B, Le Moine C, 1995. D1 and D2 receptor gene expression in the rat frontal cortex: cellular localization in different classes of efferent neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience 7, 1050–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]