Abstract

Patient-centered care requires that treatments respond to the problematic situation of each patient in a manner that makes intellectual, emotional, and practical sense, an achievement that requires shared decision making (SDM). To implement SDM in practice, tools – sometimes called conversation aids or decision aids – are prepared by collating, curating, and presenting high quality, comprehensive, and up-to-date evidence. Yet, the literature offers limited guidance for how to make evidence support SDM. Here, we describe our approach and the challenges encountered during the development of Anticoagulation Choice, a conversation aid to help patients with atrial fibrillation and their clinicians jointly consider the risk of thromboembolic stroke and decide whether and how to respond to this risk with anticoagulation.

Keywords: Shared Decision Making, Atrial Fibrillation, Stroke, Bleeding, Human-Centered Design

Introduction

Patient-centered care requires that treatments respond to the problematic situation of each patient in a manner that makes intellectual, emotional, and practical sense. Its achievement therefore requires patients and clinicians to collaborate and draw from the best available research evidence, as well as from the experience and expertise of patient and clinician. This collaboration is often called shared decision making (SDM) 1–3 and healthcare policies increasingly call for its implementation in care.4, 5

To implement SDM in practice, clinicians and patients must engage in unhurried, empathic, and productive conversations within which they clarify what is the matter and how best to respond. In determining the best response, they should uncover the relevant alternatives and draw from the results of clinical care research to understand their relative merits in responding to the patient’s situation. To assist with this requirement, promoters of SDM have developed tools, sometimes called conversation aids or decision aids,6, 7 which, among other roles, should present a collation and curation of high quality, comprehensive, and up-to-date evidence.8

The literature offers limited guidance for evidence curation to support SDM. Here, we describe our approach to and the challenges we encountered when compiling, curating and operationalizing evidence during the development of Anticoagulation Choice. This is a conversation aid to help patients and clinicians jointly consider the risk of thromboembolic stroke associated with atrial fibrillation and decide whether and how to respond to this risk with anticoagulation treatment. In focusing this account, we have mostly omitted issues of evidence appraisal, which are already well developed in the literature.8 We instead focus on how we “processed” evidence and present it in a conversation aid to make evidence support SDM.

Anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: A call for SDM

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, affecting approximately 5 million Americans and accounting for approximately US$26 billion/year in healthcare costs.9, 10 AF is associated with a 5-fold increase in the risk of stroke,4, 11 and these strokes are often more severe and more often fatal than strokes not associated with AF.11 Across a wide spectrum of individual risk, anticoagulation effectively reduces the risk of stroke on average by approximately 65%.12

Several tools to facilitate SDM in AF have been developed,7, 13, 14 but most have not been rigorously evaluated, omit newer anticoagulation options, or present outdated data.13 Additionally, most fail to directly support the discussion of practical ways in which anticoagulation affects matters important to patients such as leisure activities, diet, travel, and out-of-pocket costs.14–17 To address these limitations and support SDM conversations between clinicians and their at-risk patients with AF considering anticoagulation therapy, we developed a new conversation aid, Anticoagulation Choice.

Developing a conversation aid

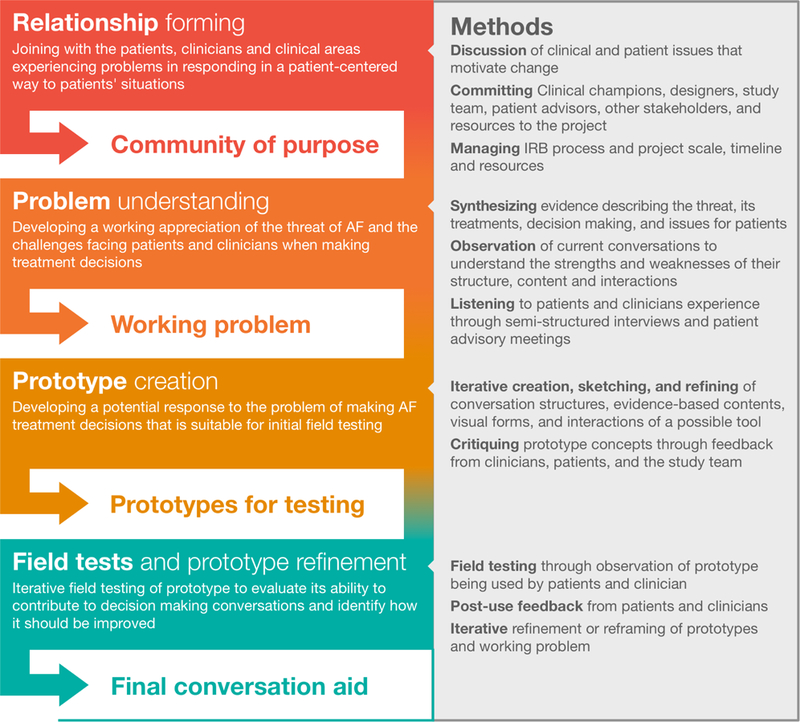

To develop Anticoagulation Choice we followed a human-centered design approach (Figure 1).18 After convening a multidisciplinary team comprised of patients, clinicians, research designers, and healthcare researchers, we sought to capture how clinicians and patients work through anticoagulation decisions in practice. For this, our team directly observed (by video recording visits or by joining those visits in person) primary and specialty clinical encounters in which decisions about anticoagulation in AF were expected to take place. Observations proceeded until we no longer generated new insights, a point arrived after observing 16 encounters with 11 clinicians, with most discussions following a similar path regardless of setting. We also looked for the resources (e.g., online stroke and bleed risk calculators) and questions that patients and clinicians drew on, the concerns stated and implied that drove deliberation, if and how an eventual decision developed in a coherent manner, and any change in the quality of care or interpersonal interactions as patients and clinicians worked together.

Figure 1.

Process for developing and prototyping conversation aids for use in the clinical encounters.

Based on encounter observations and team insights, we generated a list of necessary data to support the conversation about anticoagulation in patients with AF, i.e., to characterize (a) the situation of the patient as at-risk for thromboembolic strokes, and (b) the alternatives to mitigate this threat. We gather evidence about each of these issues, seeking reliable and current systematic reviews and, in their absence, individual studies, favoring those judged as most protected from bias.8 We sought prognostic evidence estimating baseline untreated risks of stroke and bleeding, randomized trials comparing the effect of warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) on the risks of stroke and bleeding, and population-based and large clinical and administrative database observational studies estimating their impact on outcome rates at time horizons beyond the duration of efficacy trials. In this process we identified several challenges including: lack of direct comparative effectiveness evidence for the various anticoagulants, varying time horizons, and the complexities of estimating individual out-of-pocket medication costs.

Beyond trade-offs

The classic medical formulation of the problem of anticoagulation is to set the benefits of stroke prevention against the harms of bleeding promotion.19, 20 This leads to a tendency to compare or trade-off strokes to bleeds,19, 21–23 or to ask the question of how many bleeds are acceptable in exchange for avoiding a stroke.24, 25 While this formulation follows the decision analytic logic of utility maximization, in practice we found direct comparison of strokes and bleeds to be inadequate in determining what to do as the practical and emotional implications of living with a risk of stroke or bleeds exceed the issues of utility. For example, one patient in talking with his cardiologist observed that “I’d rather be in a room with a lion than a snake.” He explained that mitigating the risk of a stroke coming out of the blue (the snake) was of greater concern than mitigating the risk of bleeding (the lion), mostly because he could “keep an eye on the lion and do something about it.” In conversations we frequently observed the issue of bleeding addressed alongside a number of other practical issues, e.g., dietary constraints, periodic monitoring requirements, interaction between anticoagulation and hobbies, travel, and recreation – that also bear on the decision to anticoagulate. In these conversations, achieving stroke prevention was central, and bleeding appeared as an adverse effect of therapy to consider and, when possible, mitigate.

Evidence challenges

Stroke Risk

To calculate stroke risk, we used the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Table 1).26 To estimate the risk of stroke without treatment based on this score we used data from a large observational cohort of patients with AF (Table 2).27 We then multiplied this estimate by the relative risk of stroke for each antithrombotic treatment option and presented the average result as the annual benefit of treatment. Compared to no treatment, warfarin decreases the risk of stroke by 64%28 and DOACs reduced stroke events (combined thromboembolic and hemorrhagic) by 19% compared with warfarin.29 When converted to absolute risk reductions, these differences turn out to be small across the range of usual patient stroke risks. For instance, for an individual with a CHADS-VASc score of 2, the anticipated one-year stroke risk without treatment would be ~2.5%. Anticoagulation would be expected to reduce this risk to 1.6% with warfarin and to 1.3% with DOAC (as a class). Furthermore, there are even smaller differences between the anticipated risk reductions associated with each of the DOACs. Thus, for the purpose of the Anticoagulation Choice conversation aid, we decided to make no distinction between the reduction in risk of thromboembolic stroke with warfarin and with DOACs.

Table 1.

Clinical risk factors included in the CHA2DS2-VASc scorea

| Letter | Risk Factor | Points |

|---|---|---|

| C | Congestive heart failure / LVEF ≤ 40% | 1 |

| H | Hypertension | 1 |

| A2 | Age ≥ 75 | 2 |

| D | Diabetes mellitus | 1 |

| S2 | Previous history of Stroke, TIA or TE | 2 |

| V | Vascular disease, which includes prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease or aortic plaque | 1 |

| A | Age 65 – 74 | 1 |

| Sc | Sex category = female | 1 |

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, TIA= transient ischemic attack, TE= thromboembolism.

Table 2.

Annual Risk of Ischemic Stroke by CHA2DS2-VASc Score without Anticoagulation

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | Events per 100-person years |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.2 |

| 1 | 0.6 |

| 2 | 2.5 |

| 3 | 3.7 |

| 4 | 5.5 |

| 5 | 8.4 |

| 6 | 11.4 |

| 7 | 13.1 |

| 8 | 12.6 |

| 9 | 14.4 |

Stroke severity

Strokes associated with AF are associated, on average, with more subsequent disability and mortality than strokes in patients without AF.11, 30, 31 The National Institute Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a widely-used scale to assess baseline stroke severity and to predict outcomes.32 Severe stroke is associated with an increased risk of death and disability, with prolonged hospital stays, and delayed recovery and improvement.32–34 To determine the proportion of patients presenting with moderate or severe stroke, we used the data from Xian et al., which considered patients with an NIHSS ≥16 (a score of 42 indicates the maximum stroke severity) as having a moderate or severe stroke.30 According to this study, 27% (95% CI 27–28%) of patients not on anticoagulation had moderate or severe strokes compared to 16% (15–17%) of those on warfarin and 18% (95% 17–18%) of patients on DOACs (p < .001). Similarly, patients on no anticoagulation had higher (p<.001) unadjusted in-hospital mortality (9.3%, 95% CI, 8.9–9.6%) compared to patients on warfarin (6.4%, 95% CI 5.8–7.0%) or on DOACs (6.3%, 95% CI 5.7–6.8%). These two outcomes (moderate/severe stroke and in-hospital mortality) were combined to indicate how many patients (out of 100) should expect fatal or highly disabling strokes without and with anticoagulation with warfarin or DOACs.

Class effects

Four direct oral anticoagulants are available in the US to prevent strokes in AF patients. These agents demand less frequent monitoring and fewer diet restrictions than warfarin. Randomized trials have generally demonstrated similar efficacy and improved safety (fewer intracranial bleeds) compared to warfarin.35–38 To date, however, no randomized trials have compared DOACs to each other, and the available evidence from observational analyses and from indirect comparisons using trial data warrant low confidence in their estimates. Therefore, we opted to consider all four agents as similar enough to convey a DOAC class-effect of effectiveness and safety when deciding how to anticoagulate. As high-quality comparative effectiveness data emerge, we may reassess the practicality of offering estimates by drug and dose, and after considering drug-drug and drug-patient (e.g., renal function) interactions.

Bleeding risk presentation

A key judgment in developing Anticoagulation Choice required accommodating the range of appropriate views about the use of bleeding risk in making anticoagulation decisions observed in practice. The most straightforward way of discussing bleeding risk involves patients and clinicians acknowledging the possibility of bleeding, the situations in which bleeds might occur, and what having one entails as a potential complication of anticoagulation. With further interest, patients and clinicians can calibrate risk estimations by considering the average risk (i.e., not specific to each patient) of bleeding with anticoagulation, following the American College of Chest Physicians Guidelines approach.39 Users that choose to explore deeper layers of the tool can review the factors that contribute to the HAS-BLED calculation and their potential mitigation. Finally, if a quantification seems necessary, users can review if the HAS-BLED estimation for the patient is at, above, or below average and an ordered icon array shows this estimation in the same time frame used to present stroke risk. Our field testing showed that this approach supports conversations across a range of preferences for information, and position bleeding as another consideration in determining how to respond to the threat of thromboembolic strokes.

Estimating Bleeding Risk

Major bleeding describes loss of blood that is either fatal or life-threatening and requiring emergency treatment and hospital admission. To determine and predict major bleeding, we used the HAS-BLED scoring system (Table 3).22, 40 In the cohorts we examined, however, the bleeding estimates HAS-BLED produced directly did not differ between patients using anticoagulants and those not anticoagulated. Therefore, we took an indirect approach. To determine a patient’s baseline annual risk of major bleeding for each HAS-BLED category, we used the following formula:

Table 3.

Clinical Risk Factors in the HAS-BLED Scoring Systema

| Letter | Risk Factor | Points |

|---|---|---|

| H | Hypertension: uncontrolled (systolic > 160 mm Hg) | 1 |

| A | Abnormal kidneyb and liverc function (1 point each) | 1 or 2 |

| S | Stroke: previous history of strokes, particularly lacunar strokes | 1 |

| B | Bleeding history or predisposition (anemia) | 1 |

| L | Labile INRs: less than 60% time in therapeutic range | 1 |

| E | Elderly: age over 65 years | 1 |

| D | Drugs or alcohold: antiplatelet agents or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory drugs, or alcohol excess (1 point each) | 1 or 2 |

INR = international normalized ratio

Abnormal kidney function indicated by need for chronic dialysis, renal transplantation, or serum creatinine ≥ 200 μmol/L.

Abnormal liver function indicated by chronic hepatic disease, such as cirrhosis, or biochemical evidence of impairment, such as bilirubin > 2x upper limit normal in association with aspartate aminotransferase/alanine amino-transferase/alkaline phosphatase > 3x upper limit normal.

Alcohol excess > 8 units per week

Data for the numerator were drawn from a large US administrative claims database (Table 4),41 which uses codes and algorithms to define baseline comorbidities and outcomes such as major bleeding.42 These algorithms are commonly used and have demonstrated good performance in several validation studies.43–45 Data for the denominator came from a meta-analysis by Ruff et al29 in which DOACs were associated with a 14% lower risk of major bleeding in comparison to warfarin and from two meta-analyses of randomized trials demonstrating that warfarin increases the risk of bleeding by 130%−200% vs. no anticoagulation therapy.46, 47 Of note, several clinician partners engaged during the tool design process pointed to reports that nurse-driven protocols in dedicated anticoagulation clinics may result in lower-than-predicted bleeding rates with warfarin use.48, 49

Table 4.

Annual Risk of major bleeding by HAS-BLED Score

| Events per 100-person years |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| HAS BLED | Baseline risk (no therapy) | Warfarin | DOACs |

| 0–1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 2.4 |

| >=3 | 2.7 | 8.1 | 6.5 |

Time Horizons

Conveying stroke and bleed risks in the conversation aid required selecting a sensible and uniform (i.e., the same for benefits and risks) time horizon. Available risk calculators estimate the 1-year stroke risk. Bleeding events in trials of warfarin and DOACs were collected over 2 to 3 years.12 While these estimates are informative, AF and its treatment are long-term matters. In addition, different patients may care about different time horizons based on their personal or clinical situations. After consultations with patients and expert clinicians, we opted to present both one-year and five-year risk estimates, the latter a long-enough horizon for decision making less affected by the contingencies that inevitably arise with longer time scales, such as competing risks for stroke, bleeding and other comorbid events. To convert the 1-year risk to a 5-year risk of stroke and of bleeding, we used the following formula:50, 51

To our knowledge, the linear relationship of risk over time that this formula assumes, while reasonable, has not been verified.

Practical issues: out-of-pocket costs

Similar judgements were necessary to facilitate discussions focused on the practical issues involved in using anticoagulation in daily life, but the most vexing involved consideration of out-of-pocket costs. Given the complexity of drug benefit plans in the U.S. and the current disconnection between pharmacy-benefit information systems and clinical record systems, we were not able to determine the out-of-pocket cost of each medication for each patient. Yet, it became clear in our observations that out-of-pocket costs are important determinants of how to proceed, particularly given the differences in drug and monitoring costs between warfarin and DOACs. To address this need, we used data from a public web-based service.52 Table 5 shows the most affordable prices we found on this service on February 3rd 2018 for each medication. The cost of INR monitoring also varies broadly across clinical settings, monitoring modality, and health plans. We used data on the systematic review by Chambers et al to estimate the average between the lowest and the highest price reported for INR monitoring.53 We resolved the dilemma between offering no estimates and offering potentially inaccurate estimates in the direction of the latter as our prior work suggested that offering cost information is more likely to trigger cost conversations and planning for the “sticker shock,” a key driver of primary nonadherence.54

Table 5.

Estimated annual out-of-pocket cost

| DOAC-Yearly cost | Apixaban 5mg twice daily | Dabigatran 150mg twice daily | Edoxaban 60mg once daily | Rivaroxaban 20mg once daily | Average cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $4,876.00 | $4,575.00 | $4,090.00 | $4,460.00 | $4,500.25a | |

| WarfarinYearly cost | Generic 5mg once daily | INR monitoring lowest price | INR monitoring highest price | INR monitoring average cost | Generic warfarin + INR average cost |

| Based on 8 tests per year | $40.00 | $73.28 | $710.08 | $391.68 | $431.68a |

Rounded to nearest $50 in the Anticoagulation Choice conversation aid

From a complex and uncertain evidence base to a conversation aid

The work of presenting evidence-based information within conversation aids is, as we have demonstrated, a matter of judgment. To limitations in the validity of the evidence of comparative effectiveness and safety across available anticoagulation agents, we must add limitations in the validity of risk estimations, particularly those arising from the HAS-BLED calculator and from legacy clinical trial reports that precede dedicated nurse-led anticoagulation clinics, and the virtual impossibility to present reasonably accurate cost information that would show the relative differences in out-of-pocket costs between anticoagulating with warfarin or with DOACs. Judgments had to consider what to include and how to present it. For these design decisions we applied and combined methods we have used in the last decade to produce conversation aids that have proven effective in clinical trials55 focused on risk communication (e.g., Statin Choice56) or option presentation (e.g., Diabetes Choice57).

Anticoagulation Choice was organized following a conversational inquiry rubric.58 First, the tool presents the (1-or 5-year as per user selection) risk of stroke (and of severe strokes) without anticoagulation. This invites a discussion of the current situation and a determination of whether the threat of thromboembolic stroke demands action. Then the tool presents anticoagulation as a possible response to this situation by showing how these stroke risk estimates change with anticoagulation. For these presentations, we use an ordered icon array with both positive and negative framing using numbers and words; this format enables both detailed and at-a-glance or gist comparisons If patient and clinician determine that anticoagulation is what the situation demands, then they move on to the second phase of the tool to determine how to anticoagulate.

Phase two of the tool starts with fostering choice awareness. This is done through an explicit statement that in order to choose between anticoagulation approaches, patients and clinicians need to think through how the alternatives fit in the patient’s life. Anticoagulation Choice then presents key issues that distinguish the available options: risk of bleeding, reversibility, need to restrict diet, out-of-pocket costs, and monitoring requirements. The most salient issue or issues vary across patients, so patients and clinicians review the pertinent ones in order of patient priority until it becomes clear which anticoagulant makes most sense. The tool then supports documentation of the decision into the medical record and produces a report for the patient. The final version of Anticoagulation Choice can be accessed here: http://anticoagulationdecisionaid.mayoclinic.org.

On judgments

The process described cannot follow rules or recipes but is reliant on collaborating with experts in curating evidence, directly observing practice as is, and field-testing subsequent versions or prototypes to learn more about what is necessary to make SDM happen for patients with AF considering anticoagulation. This process reflects our commitment to designing for context, development in partnership with end-users, and going beyond presenting information to supporting productive conversations.

Design for context

For the final tool to become normalized in practice, we must realize that issues of routine implementation are issues of design, thus, SDM tools need to fit the people, environments, and workflows in which they will be used. In the development of Anticoagulation Choice we observed and field tested prototypes in a number of contexts within our institution that serve patients with AF including primary care, emergency medicine, cardiology, anticoagulation clinics, and thrombophilia subspecialty clinics. In addition, recognizing that care varies across organizations, we also sought input during development from institutions that would be our eventual partners in the randomized trial evaluating the tool59 — an urban safety-net hospital and a metropolitan healthcare system – to ensure that it served their needs, patients, and operating context. Context also informed our tolerance for the imprecisions and inaccuracies of the data available. Anticoagulation Choice must function in busy and interactive environments in which useful and judicious approximations may suffice. The inaccuracies of out-of-pocket costs may represent a greater limitation, but one that should resolve over time with improvements in interoperability between medication benefit and clinical systems.

Development in partnership

From the beginning of the development process we engaged both patient and clinician champions. The need to develop a new conversation aid arises from the problems that patients and clinicians face in responding to illness or the threat of illness — in this instance AF and its associated threat of stroke. The development process grows out of this need and is driven by the participation of clinical champions and concerned patients. Clinical champions open doors to the clinical encounters (rather than mock or simulated encounters) in which tool prototypes are field tested, refined, and tested again. Conversations with patients who used a prototype with their clinician provide momentum for confirming the accomplishments of the current prototype and for pushing it further into the next version. In the development of Anticoagulation Choice, generalist and specialist physicians and nurse practitioners pushed the project forward recognizing its potential to contribute to their work. In so doing, they allowed us to learn from their patients. These patients, in turn, generously contributed to our work by reflecting on the experience of talking through anticoagulation with their clinicians with and without the evolving conversation aid.

Conversation not information

Care does not arise from information or from choice,60 but information and deliberation contribute to formulating care that makes sense for and adequately responds to the patient’s situation. The process by which a sensible path forward emerges is the conversation between patients and clinicians. Although they are expected to draw from the best available research evidence, information alone cannot create the meaningful conversations in which patients and clinicians do this work.

In AF, the risk of stroke looms large making it important to communicate and understand that this risk exists and to appreciate its magnitude. We found, however, that addressing the problem of what to do about that risk is also important, if not more so.60 Providing patients with more information or clearer information cannot by itself resolve this problem. Which information is useful for a particular patient, how it is useful, and how it should be used is determined by its ability to contribute to forming care that addresses the particular patient’s situation. A purpose of SDM conversation is to enable patients and clinician to uncover, adapt, and use any information that helps them work through what to do and discover a course of action that makes intellectual, practical, and emotional sense for the person and their situation.

Some approaches to SDM ask patients to work alone through the information provided via patient decision aids,7 and to bring their conclusions and questions to their clinicians. We believe that the encounter of patient and clinician is an appropriate place for working through what to do. For this reason, we observed and learned from the work that takes place in patient-clinician conversations in which actual decisions about anticoagulation took place, rather than rely exclusively on the expertise and opinions of patients, clinicians, and researchers in focus groups or simulated environments.

Conclusion

Anticoagulation Choice offers the opportunity to reflect on the process of incorporating evidence of different quality into the content of a conversation aid for use in practice to address the problems of patients living with AF. Along with the process of evidence synthesis and presentation, we relied on observations of clinical encounters, input from patients and expert clinicians, and iterative field testing of evolving prototypes to arrive at a tool that is ready to undergo (and is undergoing) formal evaluation in a clinical trial (Figure 1). This method enables us to consider implementation issues as we design for context. It also requires generous partnerships in which clinicians and patients not only give us access to their encounters but also tolerate the limitations of low-fidelity versions of the tool we field test as they make real-life decisions about treatment. Our commitment to enable useful conversations and not just provide information about risk and options further supports the work patients and clinicians do in practice. Ultimately, the goal of SDM is to identify a sensible treatment strategy for each patient. This goal is best achieved through careful patient-centered conversation. Conclusions about the extent to which Anticoagulation Choice can support this goal await the results of an ongoing randomized trial of Anticoagulation Choice versus usual care of at-risk patients with AF.59

Shared Decision Making for Atrial Fibrillation (SDM4AFib) Trial Investigators

Steering Committee

Principal Investigator: Victor Montori, MD

Study statistician: Megan E. Branda, MS

Co-investigators: Juan Pablo Brito, MD, Marleen Kunneman, PhD, Gabriela Spencer-Bonilla, MD

Study coordinator: Angela L. Sivly

Study manager: Kirsten Fleming, BA

Site Principal Investigators: Bruce Burnett, MD (Park Nicolette-Health Partners, Minneapolis, MN), Mark Linzer, MD (Hennepin Healthcare System, Minneapolis, MN), and Peter A. Noseworthy, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).

Site Teams (alphabetical order)

Hennepin Healthcare System: Haeshik Gorr, MD, Mark Linzer, MD, Jule Muegge, Sara Poplau, Benjamin Simpson, Miamoua Vang, and Mike Wambua.

Mayo Clinic: Joel Anderson, Emma Behnken, Fernanda Bellolio, MD, Juan Pablo Brito, MD, Renee Cabalka, Michael Ferrara, Kirsten Fleming, BA, Rachel Giblon, MS, Ian Hargraves, PhD, Jonathan Inselman, MS, Marleen Kunneman, PhD, Annie LeBlanc, PhD, Victor Montori, MD, Peter Noseworthy, MD, Marc Olive, Paige Organick, Nilay Shah, PhD, Gabriela Spencer-Bonilla, MD, Anjali Thota, Henry Ting, MD, Derek Vanmeter, and Claudia Zeballos-Palacios, MD.

Park Nicollet-Health Partners: Bruce Burnett, MD, Lisa Harvey, and Shelly Keune.

Data Safety and Monitoring Board

Gordon Guyatt, MD (chair), Brian Haynes, MD, and George Tomlinson, PhD.

Expert advisory panel

Paul Daniels, MD, Bernard Gersh, MD, Erik Hess, MD, Thomas Jaeger, MD, Robert McBane, MD, and Peter Noseworthy, MD (chair).

Acknowledgements

We express our wholehearted gratitude to all clinicians and patients who generously contributed their time and open the sanctity of their encounters to our research team. They are the reason we make sure all tools we develop and proof valuable remain in the public domain.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported in full by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL131535. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- CHA2DS2-VASc

congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke, vascular disease, sex

- DOACs

direct oral anticoagulants

- HAS-BLED

hypertension, abnormal kidney or liver function, prior stroke, prior bleeding, labile INR, age, drugs

- INR

international normalized ratio

- NIHSS

National Institute Health Stroke Scale

- SDM

shared decision making

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Claudia L. Zeballos-Palacios, Email: zeballospalacios.claudia@mayo.edu.

Ian G. Hargraves, Email: hargraves.ian@Mayo.edu.

Peter A. Noseworthy, Email: noseworthy.peter@mayo.edu.

Megan E. Branda, Email: branda.megan@mayo.edu.

Marleen Kunneman, Email: Kunneman.marleen@mayo.edu.

Bruce Burnett, Email: Bruce.Burnett@ParkNicollet.com.

Michael R. Gionfriddo, Email: mgionfriddo@geisinger.edu.

Christopher J. McLeod, Email: mcleod.christopher@mayo.edu.

Haeshik Gorr, Email: haeshik.gorr@hcmed.org.

Juan Pablo Brito, Email: brito.juan@mayo.edu.

Victor M. Montori, Email: Montori.victor@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect 2006;9:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 1997;44:681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:e1–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidenreich PA, Solis P, Mark Estes NA 3rd, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Adults With Atrial Fibrillation or Atrial Flutter: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016;9:443–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L, et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens. Bmj 2015;350:g7624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montori VM, LeBlanc A, Buchholz A, Stilwell DL, Tsapas A. Basing information on comprehensive, critically appraised, and up-to-date syntheses of the scientific evidence: a quality dimension of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13 Suppl 2:S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu BC, Dalal MR, Schulman KL. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. The American journal of cardiology 2013;112:1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates. The American journal of cardiology 1998;82:2N–9N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawfik A, Bielecki JM, Krahn M, et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of stroke prevention treatments in patients with atrial fibrillation. Clinical pharmacology : advances and applications 2016;8:93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neill ES, Grande SW, Sherman A, Elwyn G, Coylewright M. Availability of patient decision aids for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. American Heart Journal 2017;191:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarkesmith DE, Pattison HM, Khaing PH, Lane DA. Educational and behavioural interventions for anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:Cd008600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fatima S, Holbrook A, Schulman S, Park S, Troyan S, Curnew G. Development and validation of a decision aid for choosing among antithrombotic agents for atrial fibrillation. Thrombosis Research 145:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saposnik G, Joundi RA. Visual Aid Tool to Improve Decision Making in Anticoagulation for Stroke Prevention. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association 2016;25:2380–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckman MH, Wise RE, Naylor K, et al. Developing an Atrial Fibrillation Guideline Support Tool (AFGuST) for shared decision making. Current medical research and opinion 2015;31:603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witteman HO, Dansokho SC, Colquhoun H, et al. User-centered design and the development of patient decision aids: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2015;4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A. Balancing the risks of stroke and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Archives of internal medicine 2002;162:541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olesen JB, Lip GY, Lindhardsen J, et al. Risks of thromboembolism and bleeding with thromboprophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: A net clinical benefit analysis using a ‘real world’ nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overvad TF, Larsen TB, Albertsen IE, Rasmussen LH, Lip GY. Balancing bleeding and thrombotic risk with new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy 2013;11:1619–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaHaye SA, Gibbens SL, Ball DG, Day AG, Olesen JB, Skanes AC. A clinical decision aid for the selection of antithrombotic therapy for the prevention of stroke due to atrial fibrillation. European heart journal 2012;33:2163–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckman MH, Wise RE, Speer B, et al. Integrating real-time clinical information to provide estimates of net clinical benefit of antithrombotic therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. Bmj 2001;323:1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonso-Coello P, Montori VM, Diaz MG, et al. Values and preferences for oral antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: physician and patient perspectives. Health Expect 2015;18:2318–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friberg L, Skeppholm M, Terent A. Benefit of anticoagulation unlikely in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xian Y, O’Brien EC, Liang L, et al. Association of Preceding Antithrombotic Treatment With Acute Ischemic Stroke Severity and In-Hospital Outcomes Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2017;317:1057–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation wit mortality and disability after ischemic stroke. Neurology 2013;81:825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams HP Jr., Davis PH, Leira EC, et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology 1999;53:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Lindeman E. Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke: facts and theories. Restorative neurology and neuroscience 2004;22:281–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Acute stroke: prognosis and a prediction of the effect of medical treatment on outcome and health care utilization. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Neurology 1997;49:1335–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine 2009;361:1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine 2011;365:981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine 2011;365:883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine 2013;369:2093–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines; Chest 2012;141:e601S–e636S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, McBane RD, Shah ND. Direct Comparison of Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, and Apixaban for Effectiveness and Safety in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2016;150:1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao X, Abraham NS, Alexander GC, et al. Effect of Adherence to Oral Anticoagulants on Risk of Stroke and Major Bleeding Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT Jr. Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke 2002;33:2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA. An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 2011;20:560–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnason T, Wells PS, van Walraven C, Forster AJ. Accuracy of coding for possible warfarin complications in hospital discharge abstracts. Thromb Res 2006;118:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen LV, Vestergaard P, Deichgraeber P, Lindholt JS, Mortensen LS, Frost L. Warfarin for the prevention of systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2008;94:1607–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segal JB, McNamara RL, Miller MR, et al. Prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation. A meta-analysis of trials of anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs. Journal of general internal medicine 2000;15:56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qvist I, Hendriks JM, Moller DS, et al. Effectiveness of structured, hospital-based, nurse-led atrial fibrillation clinics: a comparison between a real-world population and a clinical trial population. Open Heart 2016;3:e000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sjogren V, Grzymala-Lubanski B, Renlund H, et al. Safety and efficacy of well managed warfarin. A report from the Swedish quality register Auricula. Thromb Haemost 2015;113:1370–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller DK, Homan SM. Determining transition probabilities: confusion and suggestions. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making 1994;14:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naglie G, Krahn MD, Naimark D, Redelmeier DA, Detsky AS. Primer on medical decision analysis: Part 3--Estimating probabilities and utilities. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making 1997;17:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.https://www.goodrx.com/ Accessed Feb 2018.

- 53.Chambers S, Chadda S, Plumb JM. How much does international normalized ratio monitoring cost during oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist? A systematic review. International journal of laboratory hematology 2010;32:427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bora P, Inselman J, Castaneda-Guarderas A, et al. Introducing cost to consciousness, consultation, and conversations via decision aids. International Shared Decision Making Conference, Australia 2015.

- 55.Montori VM, Kunneman M, Brito JP. Shared Decision Making and Improving Health Care: The Answer Is Not In. JAMA 2017;318:617–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weymiller AJ, Montori VM, Jones LA, et al. Helping patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus make treatment decisions: statin choice randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1076–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mullan RJ, Montori VM, Shah ND, et al. The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1560–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.JafariNaimi N, Nathan L, Hargraves I. Values as Hypotheses: Design, Inquiry, and the Service of Values. Design Issues 2015;31:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kunneman M, Branda ME, Noseworthy PA, et al. Shared decision making for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, Montori VM. Shared Decision Making: The Need For Patient-Clinician Conversation, Not Just Information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:627–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]