Abstract

Purpose of review

This review summarized the recent evidence on the performance of population-based Hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening, published and indexed to PubMed, in the U.S. during the two-year window from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2018.

Recent findings

A majority of the selected articles in this review focused on the birth cohort 1945–1965 because of the HCV screening recommendations released after August 2012. However, the articles for the high-risk population applied to all ages because the recommendations for this specific population have remained largely unchanged since 1998. The reported rates of HCV screening varied substantially not only across the three different populations (i.e., general, underserved, and high-risk) but also within each population.

Summary

More vigilant monitoring of HCV screening performance of younger birth cohorts is needed because these individuals have been experiencing a higher incidence of HCV infection than those in the birth cohort 1945–1965. In addition, to meet the goal of eliminating HCV infection as a U.S. public health problem by 2030, significant improvement in more accurately and comprehensively reporting the trends in population-based HCV screening across different populations is warranted in the future.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, screening, recommendations, population-based

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer in the U.S., and approximately 2.7 to 3.9 million Americans are estimated to be currently infected with HCV [1]. The prevalence of HCV infection varies by birth cohort, socio-economic status (SES), and other risk factors. In the 2003–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of nationally representative non-institutionalized U.S. civilian population, the prevalence of HCV infection was the highest among the birth cohort 1945–1965 at 3.0%, followed by the birth cohort 1966–1976 at .8% [2]. The prevalence of HCV infection of the lower SES, such as the medically underserved population, is higher than that of the higher SES. In addition, the prevalence may be significantly higher among individuals who use illicit drugs, are co-infected with other viral infections, and are born to HCV-infected mothers [1, 3].

However, many of the HCV-infected are not aware of their infection and thus unable to receive highly effective anti-viral treatment. In August 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidelines by recommending universal HCV screening for the entire birth cohort 1945–1965, regardless of the history of risk for HCV infection [1]. The recommendation for screening patients with other risk factors (e.g., illicit drug use, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, birth to HCV-infected mothers) remained largely unchanged from the previous recommendation [1, 3]. A two-step blood test sequence is recommended by the CDC for identifying HCV infection: (1) a HCV antibody test ordered to detect HCV, and (2) a HCV RNA test ordered to confirm HCV infection in the setting of a positive HCV antibody test. Shortly thereafter the release of the CDC recommendation, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued the similar recommendation in July 2013 [4], and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the largest federally-funded integrated health care system, also issued the same recommendation for screening of the birth cohort 1945–1965 in January 2014 [5].

This review summarized the recent evidence on population-based screening of HCV infection published and indexed to PubMed during the two-year window from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2018. This article specifically focused on the evidence generated in the U.S., largely because of the recommendations of one-time universal screening for the birth cohort 1945–1965. In the end, this review highlights some recommendations for strengthening the existing evidence on population-based screening, given the rising concern over younger birth cohorts who are at higher risk for HCV because of the current opioid epidemics in the U.S. [6–7].

Text of review

Method

We conducted a search of the key words of “hepatitis C (or HCV) screening (or testing)” from articles based on U.S. experience, published in peer-reviewed journals and indexed to PubMed from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2018. We further excluded articles that reported HCV screening rates following randomized or observational interventions (e.g., electronic clinical reminders) designed for increasing screening rates.

Results

This review identified a total of twenty articles (Table 1), in which eight articles were relevant to the general population (e.g., the non-institutionalized, childbearing-age women, Veterans, and beneficiaries in the military system), four to the underserved population (e.g., Medicaid enrollees, users of safety-net clinics, visitors of emergency departments or EDs), and eight to the high-risk population (e.g., users of illicit drugs, the HIV-infected, children born of HCV-infected mothers, prisoners).

Table 1.

Summary of Selected Articles of HCV Screening Rates Published from 2017 to 2018

| Reference | Population | Data sources | Study Design | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Population | ||||

| Patel et al. [8] | Birth cohorts 1945–1965 & 1966–1994 | 2013–2017 National Health Interview Survey | Longitudinal | The rates increased from 12.3–17.3% from 2013 to 2017 of the birth cohort 1945–1954, and 13.2–16.8% of the birth cohort 1966–1994, respectively. |

| Jemal et al. [9] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 | 2013 & 2015 National Health Interview Survey | Cross-sectional | The rates increased from 12.3% in 2013 to 13.8% in 2015. |

| Barocas et al. [10] | Birth cohorts 1945–1965 & after 1965, commercially insured | 2010–2014 MarketScan claims data | Quasi-experimental | There was a 49.0% increase in screening rates of the birth cohort 1945–1964 after 2012 CDC recommendation. |

| Isenbour et al. [11] | All-ages, commercially insured | 2004–2014 MarketScan claims data | Longitudinal | The rates increased from 1.1–2.5% between 2005 and 2014 of all ages. Younger enrollees had higher rates, and the rates of the birth cohort 1945–1965 increased 91.0% from 1.7–3.3% between 2011 and 2014. |

| Carlucci et al. [12] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 of insured Tennesseans | 2013–2015 HCV surveillance and claims data from Tennessee Department of Health. | Cross-sectional | The rate was 7%. |

| Schillie et al. [13] | Childbearing-age women, pregnant women, and children <5 | 2011–2016 commercial laboratory data from a single company | Cross-sectional | The rates increased from 6.1–8.4% among childbearing age women between 2011 and 2016, 5.7–13.4% among pregnant women, and .5-.6% among children, respectively. |

| Ross et al. [14] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 Veterans who used VA health care | 2013–2016 VA nationwide claims data | longitudinal | The rates increased from 65.5% to 73.4% between 2013 and 2016. |

| Manjelievskaia et al. [15] | Birth cohort 1945–1965, Department of Defense beneficiaries | A 5% sample of claims from Military Health System Data from 2011 to 2013 | Cross-sectional | The rates were 1.7% prior to the CDC recommendation and 2.4% afterward. |

| Underserved Population | ||||

| Flanigan et al. [16] | Birth cohort 1945–1965, New York Medicaid enrollees | New York Medicaid claims from 2012–2014 | longitudinal | The monthly rates increased from .8% in 2012, to .9% in 2013, to 1.3% in 2014.1 |

| Kim et al. [17] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 in safety-net clinics | 2014–2016 electronic health records data | Cross-sectional | The rate was 99.7% during the period. |

| Wong et al. [18] | Patients ≥ 18 who underwent outpatient endoscopy at a large urban safety-net hospital | 2015–2016 electronic health records data | Cross-sectional | The rate was 30.9%. |

| Cornett et al. [19] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 during ED visits | 2016 claims data from a single hospital | Cross-sectional | (At least) 20.9% patients were screened during ED visits.2 |

| High-Risk Population | ||||

| Noska et al. [20] | All-age homeless Veterans who used VA health care | 2015 VA nationwide claims data | Cross-sectional | The rates were 78.1% of homeless Veterans and 59.5% of non-homeless Veterans, |

| Lazar et al. [21] | Persons ≥ 18 with HIV infection in a single New York City clinic | 2012 commercial laboratory data | Cross-sectional | The rate was 25.8%. |

| Chappell et al. [22] | Children of HCV-infected mothers | 2006–2014 claims data from a single hospital | Cross-sectional | The rate was .9%. |

| Watts et al. [23] | Children born form HCV-infected mothers in Wisconsin Medicaid | 2011–2015 Wisconsin Medicaid claims data | Cross-sectional | The rate was 34.0%. |

| Soipe et al. [24] | Young adults age18–29 who used non-medical prescription opioids | 2015–2016 self-reported HCV screening status from the Rhode Island Young Adults Prescription Drug Study | Cross-sectional | The rate was 78.6%. |

| Lambdin et al. [25] | Drug users ≥ 18 in Oakland, California | 2011–2013 self-reported HCV screening status data | Cross-sectional | The rate was 32.0%. |

| Epstein et al. [26] | All women with opioid use disorder who delivered live births in a single medical center | 2006–2015 registry data | Cross-sectional | The rates were 85.0% of the women, and 68.0% of the infants. |

| Akiyama et al. [27] | Birth cohort 1945–1965 in New York City jail system | 2013–2014 claims data from New York City correctional health providers | Cross-sectional | The rate was 63.7%. |

Only monthly rates were reported.

The denominator was estimated based the number of patients in that birth cohort during the entire year of 2016.

General population

Two articles used the annual National Health Interview Survey, representing non-institutionalized U.S, civilian population, to report HCV screening rates. Using self-reported HCV screening status, Patel et al. estimated that the screening rates increased from 12.3% in 2010, to 13.3% in 2015, and to 17.3% in 2017 among the birth cohort 1945–1965 [8]. The corresponding percentages were 13.2%, 14.0%, and 16.8% for the birth cohort 1966–1994. Jemal et al. reported the consistent rates of 2013 and 2015 for the birth cohort 1945–1965 [9].

Screening rates for the commercially insured were reported in three articles. Barocas et al. examined the impact of the 2012 CDC universal screening recommendation on the likelihood HCV screening among the commercially insured born between 1945 and 1965 [10]. In this well-conducted quasi-experimental analysis, which incorporated the birth cohort after 1965 as a control and the pre and post-recommendation periods, the authors reported that during the 3 years prior to the recommendation (2010–2012), the birth cohort 1945–1965 had lower screening rates of 1.1–1.4% in comparison to the control of 2.1–2.5%. During the 2-year period after the recommendation, the rates for the birth cohort 1945–1965 increased from 2.0% to 2.5% in comparison to the increased rates of 2.4% to 2.6% for the control. Their multivariable analysis suggested that the CDC-recommendation increased the screening rates of the targeted birth cohort by approximately a 1.0-percentage-point (or 49.0%). (The validity of the results of this article hinged on two assumptions: (1) no spillover effects of the recommendation of the targeted birth cohort to the control birth cohort, and (2) the 2013 USPSTF recommendation of 2013 as a mediator of the 2012 CDC recommendation.) A second article by Isenhour et al. used similar data and reported consistent screening patterns [11]. A third article of Tennesseans in the birth cohort 1945–1965 reported an HCV screening rate of 7.0% during the period between 2013 and 2015 [12].

Using 2011–2016 laboratory claims data from a single commercial company, Schillie et al. examined the performance of HCV screening among women and children. The investigators found that the screening rate increased by 39.0% (6.1–8.4%) among all childbearing-age women, by 135.0% (5.7–13.5%) among pregnant women, and by 25.0% (.5-.6%) among children under age 5, respectively [13].

Two additional articles reported the HCV screening experience of Veterans in the VA and of beneficiaries in the U.S. military health care system. Using VA claims data, Ross et al. reported the HCV screening rate among Veterans in the birth cohort 1945–1965 who ever used VA services and ever tested for HCV infection from fiscal years 2014 to 2016, a post-period of VA’s adoption of the CDC recommendation [14]. During the 3-year period, the rate increased from 65.8% in 2014, to 68.8% in 2015, and to 73.5% in 2016. Manjelievskaia et al. used the U.S. Department of Defense Military Health System Repository claims data to estimate the HCV screening rates before and after the CDC recommendation among the studied beneficiaries in the birth cohort 1945–1965 [15]. Their reported rates increased from 1.7% during the pre-recommendation period (July 2011 to July 2012) to 2.4% during the post-recommendation period (September 2012 to September 2013).

Underserved population

Flanigan et al. reported the screening rates of New York (NY) Medicaid enrollees in the birth cohort 1945–1965, using claims database from 2012 to 2014 [16]. The estimated monthly rates rose from .8% in 2012, to .9% in 2013, and to 1.3% in 2014, the year when the NY-mandated provision of HCV screening services to the birth cohort 1945–1965 took effect. A second article by Kim et al. reported 99.7% HCV screening rate of individuals in the birth cohort 1945–1965 who used the safety-net clinics in the San Francisco Health Network from October 2014 and October 2016 [17]. (Among the screened, 4.3% had a RNA test without an HCV antibody test.) A third article by Wong et al. reported the rate of 30.9% among patients ≥ 18 years old who underwent outpatient endoscopy in an urban safety-net hospital [18]. Because use of EDs may be viewed as a proxy for lack of access-to-care, a fourth article by Cornett et al. reported a minimum 20.0% HCV screening rates of patients in the birth cohort 1945–1965 who visited the ED in a single academic teaching hospital in New Jersey from June 2016 to December 2016 [19].

High-risk population

Using VA claims data, Noska et al. examined the HCV screening rates among all-age homeless and non-homeless Veterans who used VA health care services in 2015 [20]. The investigators found that 78.1% of these homeless Veterans had ever tested for HCV infection, compared to 59.5% of non-homeless Veterans.

Three articles examined the viral-infected population. An article by Lazer et al., who studied HCV screening patterns of HIV-infected population from a single New York City clinic in 2012, found that 79.5% were tested for HCV infection [21]. Other two articles focused on the HCV screening rates of HCV-infected mothers and their children. Using claims data, Chappell et al. reported .9% HCV screening rate of children born from HCV-infected women during pregnancy in a single hospital within the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from 2006 to 2014 [22]. After analyzing 2011–2015 Wisconsin Medicaid claims data, Watts et al. reported the screen rate of 34.0% among children born to HCV-infected mothers [23].

Three additional articles reported HCV screening patterns of users of illicit drugs. Using self-reported data from the Rhode Island Young Adults Prescription Drug Study, an article by Soipe et al. of young adults 18–29 years old who used opioids without prescription reported HCV screening rate of 78.6% from January 2015 to February 2016 [24]. A second article by Lambdin et al. reported a screening rate of 32.0%, based on the self-reported past HCV screening experience, among drug users ≥ 18 years old living in Oakland (California) from 2011 to 2013 [25]. Using the 2006–2015 claims data from a single medical center, a third article by Epstein et al. estimated the screening rates of 85.0% of women with opioid use disorder who gave live births, and of 68.0% of the children born from these women [26].

Akiyama et al. studied HCV screening in the high risk incarcerated population. The authors reported an HCV screening rate of 63.7% among the prisoners in the birth cohort 1945–1965 in New York City Jail System from June 2013 to June 2014 [27].

Conclusion

A majority of the selected articles in this review focused on the birth cohort 1945–1965 because of the HCV screening recommendations released after August 2012. However, the articles for the high-risk population encompassed all ages because the recommendations for these patients have remained largely unchanged since 1998 [1, 3].

Our review of the reported rates of HCV screening, published in 2017 and 2018, reveals substantial variability across the three different populations (i.e., general, underserved, and high-risk). Across these three populations defined in this article, the high-risk population generally had the highest HCV screening rates, followed by the underserved and general populations. Among all the populations included in this review, the VA was a shining example of successfully screening Veterans (including high-risk homeless Veterans), targeted by the recommendations [5]. As of September 2017, the VA reported 79.5% of Veterans in the targeted birth cohort had been tested with HCV antibody [5].

It is surprising that the reported screening rates also varied significantly within each of the three populations. Among the general population, the two articles using the National Health Interview Survey data of non-institutionalized U.S. civilians in the birth cohort 1845–1965 reported the screening rate of approximately 13.3% in 2015 [8–9]. However, the other two articles of nationally representative commercially insured enrollees only reported the rates less than approximately 2.5% (or a fifth of the rates reported in the articles of the National Health Interview Survey) [10–11]. Among the high-risk population, one study of children born to HCV-infected pregnant mothers reported less than 1.0% of these children tested for HCV infection from a single hospital during a 9-year period [22]. However, the article of the children in Wisconsin Medicaid born to HCV-infected mothers reported a screening rate of 34.0% between 2011 and 2015 [23].

The variation in HCV screening rates reported in this review may stem from a number of factors. First, the representativeness of data sources may vary. For example, the article by Barocas et al. estimated HCV screening rates using commercially insured population (e.g., without Medicare fee-for-service or Medicaid beneficiaries), which may be different from the population in the National Health Interview Survey [8–10]. Second, the measurement of HCV screening status may also vary. Self-reported past HCV screening experience that are more likely subject to recall errors may be different from that captured in the administrative claims and electronic health records data. Third, there is a concern over whether to account history of HCV screening for measuring up-to-date HCV screening status may influence the variability of the reported rates. For example, measuring of the up-to-date screening status in a given year without examining the history of HCV screening prior to the given year may underestimate the screening rates calculated from use of both current and past HCV screening services.

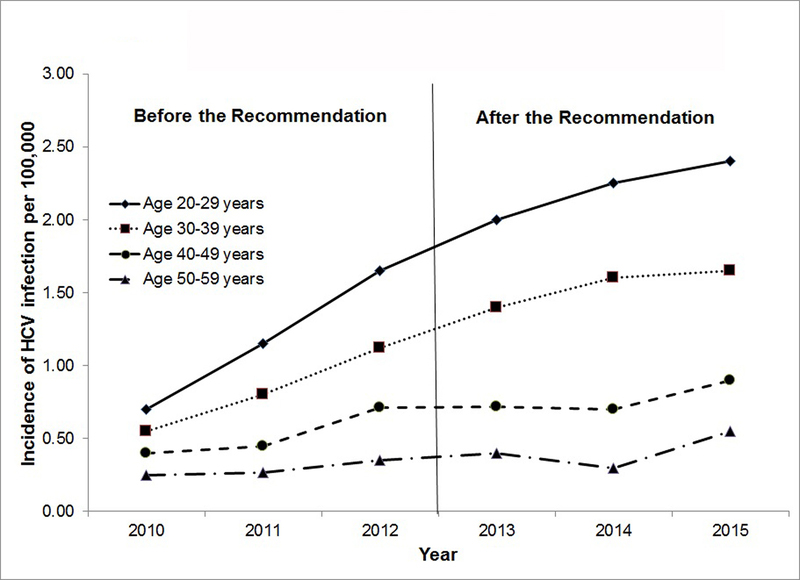

There are two main purposes of reporting of population-based HCV screening rates. The first purpose is to monitor the progress in the performance of quality of HCV care (e.g., HCV screening). A 2017 CDC report showed that the younger birth cohorts are at the higher incidence of HCV infection from 2010 to 2015, showed in Figure 1 [28]. (Figure 1 was specifically created for this review article, based on the information available in the CDC report.) For example, the incidence in individuals age 20–29 years old (2.4 cases per 100,000) was more than four times higher than that in individuals age 50–59 years old (0.6) in 2015. This gap in the incidence of HCV infection between the youngest and oldest cohorts has widened, driven largely by the growing opioid epidemic and the increased use of illicit drugs, such as heroin, in younger birth cohorts [6–7]. Because the focus of HCV screening recommendations have centered on the birth cohort 1945–1965, little is known about the performance of HCV screening on the birth cohort after 1965, including the performance in the VA. As a result, further efforts to report HCV screening rates are needed for the younger population.

Figure 1.

Incidence of Reported Acute HVC Infection by the CDC from 2010 to 2015

The second purpose is to better evaluate future interventions designed for improving HCV screening. There is a need for longitudinal, repeated measurement of HCV screening of representative populations at the individual or area level. One of the key strengths of this type of measurement is to better control for heterogeneity and thus allows stronger causal inferences of the impact of future interventions.

To meet the goal of eliminating HCV infection as a U.S. public health problem by 2030, significant improvement in more accurately and comprehensively reporting trends in HCV screening rates across different populations is warranted in the future [29].

Key points.

Screening rates of the birth cohort 1945–1965 have increased slightly since the universal screening recommendations for this targeted birth cohort were released.

More evidence is needed for screening rates of younger birth cohorts because these individuals are at a higher risk of HCV infection than those in the birth cohort 1945–1965.

The reported rates of HCV screening varied substantially not only across the different populations but also within each population.

More accurately and comprehensively reporting of trends in HCV screening rate across different populations is warranted in the future.

Acknowledgements

Financial support and sponsorship

Dr. Andrew Schreiner is supported by a grant from the NIDDK (1K23DK118200-01).

References

- 1.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012;61:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic diseases. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998;47:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer VA, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, et al. Curing hepatitis C virus infection: best practices from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med 2016;374:154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lankenau SE, Kecojevic A, Silva K. Associations between prescription opioid injection and Hepatitis C virus among young injection drug users. See comment in PubMed Commons belowDrugs (Abingdon Engl). 2015;22:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel EU, Mehta SH, Boon D, et al. Limited coverage of Hepatitis C Virus Testing in the United States, 2013–2017. Clin Infect Dis 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Fedewa SA. Recent hepatitis C virus testing patterns among baby boomers. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:e31–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barocas JA, Wang J, White LF, et al. Hepatitis C Testing Increased Among Baby Boomers Following The 2012 Change To CDC Testing Recommendations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017. December;36:2142–2150.*This article reported the HCV screening rates for both the 1954–1965 and after 1965 birth cohorts from 2010–2014. Using a stronger research design, the authors additionally examined the impact of the 2012 CDC recommendation on HCV screening patterns of the recommendation-targeted birth cohort.

- 11.Isenhour CJ, Hariri SH, Hales CM, et al. Hepatitis C antibody testing in a commercially insured populations, 2005–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlucci JG, Farooq SA, Sizemore L, et al. Low hepatitis C antibody screening rates among an insured population of Tennessean baby boomers. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schillie SF, Canary L, Koneru A, et al. Hepatitis C virus in women of childbearing age, pregnant women, and children. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:633–641, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross DB, Belperio PS, Chartier M, et al. Hepatitis C testing in US Veterans born 1945–1965: an update. J Hepatol 2017;66:237–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manjelievskaia J, Brown D, Shriver CD, et al. CDC screening recommendation for baby boomers and hepatitis C virus testing in the US Military Health System. Public Health Rep 2017;132:579–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanigan CA, Leung SJ, Rowe KA, Zhu K. Evaluation of the impact of mandating health care providers to offer hepatitis C virus screening to all persons born during 1945–1965 – New York, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1023–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim NJ, Locke CJ, Park H, et al. Race and hepatitis C care continuum in an underserved birth cohort. J Gen Intern Med 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4649-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong RJ, B Campbell B, Liu B, et al. Sub-optimal testing and awareness of HCV and HBV among high risk individuals at an underserved safety-net hospital. J Community Health. 2018;43:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornett JK, Bodiwala V, Razuk V, et al. Results of a hepatitis C virus screening program of the 1945–1965 birth cohort in a large emergency department in New Jersey. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy065. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and Hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States Veterans. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazar R, Kersanske L, Braunstein SL. Testing for comorbid conditions among people with HIV in medical care. AIDS Care 2018;12:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ca Chappell, Hillier SL, Crowe D, et al. Hepatitis C virus screening among children exposed during pregnancy. Pediatrics 2018;141 pii: e20173273. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watts T, Stockman L, Martin J, et al. Increased risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus among Medicaid recipients—Wisconsin, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1136–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soipe AI, Taylor LE, Abioye AI, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C screening, testing, and care experience among young adults who use prescription opioids nonmedicaly. J Adolesc Health 2018;62:114–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambdin BH, Kral AH, Comfort M, et al. Associations of criminal justice and substance use treatment involvement with HIV/HCV testing and HIV treatment cascade among people who use drugs in Oakland, California. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017;12:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein RL, Sabharwal V, Wachmen EM, et al. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus: defining the cascade of care. J Pediatr 2018;203:34–40.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akiyama MJ, Kaba F, Rosner Z, et al. Correlates of hepatitis C virus infection in the targeted testing program of the New York City Jail System: epidemiologic patterns and priorities for action. Public Health Rep. 2017;132:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Progress toward viral hepatitis elimination in the United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Infectious Diseases, NCHHSTP; 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/policy/PDFs/NationalReport.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Pr; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]