Abstract

Background:

The co-occurrence of depression and risky alcohol use is clinically-relevant given their high rates of comorbidity and reciprocal negative impact on outcomes. Emotion dysregulation is one factor that has been shown to underlie this association. However, literature in this area has been limited in its exclusive focus on emotion dysregulation stemming from negative emotions.

Objectives:

The goal of the current study was to extend research by exploring the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in depression symptom severity, risky alcohol use, and their association.

Methods:

Participants were 395 trauma-exposed adults recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform (56.20% female, Mage = 35.55) who completed self-report questionnaires.

Results:

Zero-order correlations among depression symptom severity, the three subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use were positive. Two subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions – nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties controlling impulsive behavior when experiencing positive emotions – accounted for the relationship between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use.

Conclusion:

Results suggest the importance of incorporating techniques focused on improving positive emotion regulation skills in interventions for risky alcohol use among individuals with depression.

Keywords: depression, positive emotion dysregulation, difficulties regulating positive emotions, positive emotion dysfunction, risky alcohol use

Introduction

Among adults, risky alcohol use is the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States (1), and therefore represents a significant public health concern (2). In 2015, 86.4% of adults in the United States reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their life. More than half of adults report past-month alcohol consumption (56.0%), and more than 15.1 million adults reporting problematic drinking patterns indicative of an alcohol use disorder (3). High rates of alcohol consumption expose individuals to increased risk for various negative health (4), legal (5), and social (6–8) consequences. A large body of research has found that risky alcohol use commonly co-occurs with depression (9, 10), and that depression may be a contributing factor to the development of alcohol use disorders (11–13). Nearly 41% of those meeting criteria for a major depressive disorder also have a diagnosis of lifetime alcohol use disorder and 22% meet criteria for past-12-month alcohol use disorder (14). This is concerning given that alcohol use among individuals with depression is associated with increased severity and duration of depressive episodes and likelihood of suicidal ideation, as well as decreased ability to cope with social stressors (11, 15, 16). Taken together, the above findings highlight the importance of research that extends our understanding of the co-occurrence of depression and risky alcohol use.

One potential transdiagnostic vulnerability factor that may help to explain the co-occurrence of depression and risky alcohol use is emotion dysregulation. Emotion dysregulation is a multi-faceted construct involving maladaptive responses to emotions, including: 1) a lack of awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions, 2) an inability to control behaviors when experiencing emotional distress, 3) a lack of access to situationally appropriate strategies to cope with the duration and intensity of emotions to meet situational demands, and 4) an unwillingness to experience emotional distress when pursuing meaningful activities in life (17, 18). Emotion dysregulation has been identified as a key factor underlying the etiology and treatment of both depression and risky alcohol use (19, 20). Emotion dysregulation has been found to positively relate to increased risk for depression, more severe depression symptoms later in life, and worse treatment outcomes for depression (20, 21). Likewise, emotion dysregulation has been found to be positively linked to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences (22, 23), as well as been shown to predict relapse following treatment for risky alcohol use (19). Though found to be associated independently associated with depression and risky alcohol use, research to date has not examined the role of emotion dysregulation in the depression-alcohol use relation.

Another limitation of the extant research is its almost exclusive focus on negative emotion dysregulation, despite work suggesting that individuals may also experience dysregulation stemming from positive emotions (24, 25) across domains of nonacceptance, goal pursuit, and impulse control. Preliminary theoretical and empirical evidence links these difficulties to both depression and risky alcohol use (26, 27). Depression is characterized by diminished positive affect (e.g., anhedonia) (28, 29). Some theorists have suggested that individuals with depression are unable to experience positive affect (28), perhaps due to lack of contact with reinforcing experiences and/or interfering negative cognitions (30), or an unwillingness to experience positive emotions perceived as aversive. For instance, individuals who experience depression may be more likely to experience secondary negative emotional reactions to situations or stimuli that are typically positive. This is consistent with evidence that negative affect interference, the tendency to experience negative emotions in situations that typically elicit positive emotions, predicts hedonic decline and anhedonia (symptoms of depression) (31). Alternatively, individuals with depression may come to fear positive emotions over time, perhaps because they elicit negative emotions or because of concern that they will lose control over their emotions or their behavioral responses to emotions (32). Consistent with the idea that individuals with depression may be nonaccepting of positive emotional experiences, greater depression symptom severity has been shown to relate to increased suppression of positive emotions (33). It is also possible that positive emotions lead to behavioral dyscontrol among individuals with depression. Indeed, depression is also associated with positive urgency, or the tendency to act rashly when experiencing extreme positive emotions (34). Further, individuals with depression show altered reward processing (35), suggestive of impairment in behavioral control in the context of positive emotions.

Increasing research also provides support for the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in risky alcohol use. Individuals who are nonaccepting of positive emotions may use alcohol to alleviate or distract from positive emotional states, consistent with negative reinforcement models of alcohol use (36). Further, positive emotions may be associated with behavioral dyscontrol, which may take the form of risky alcohol use. For instance, positive emotional states may increase distractibility (37) and lead to less discriminative use of information causing one to drink alcohol (38), heightening the risk for disadvantageous decision-making focused on short-versus long-term goals (39). Regarding empirical findings, only a few studies have examined the role of other facets of difficulties regulating positive emotions in risky alcohol use. Weiss, Forkus, Contractor, and Schick (26) found that nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties controlling impulsive behavior and engaging in goals-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions were associated with risky alcohol use among college students. A second study found that overall difficulties regulating positive emotions moderated the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and alcohol use to cope with social stressors, such that positive affect stemming from social stressors predicted alcohol use to cope with social stressors among individuals with high (but not low) levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions (27). Finally, a third study found support for three classes of domestic violence-victimized women characterized by difficulties regulating negative and positive emotions, and alcohol misuse was more prevalent among the class defined by higher levels of difficulties regulating both negative and positive emotions (40).

The goal of the current study was to address these above-mentioned gaps in the literature by exploring the relations among depression severity, subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use. We expected that depression severity, subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use would be significantly positively correlated. Further, we expected that the subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions would help to explain the relation between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use.

Methods

Procedure/Participants

Participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform. Beyond generating reliable data (41, 42), MTurk’s subject pool is diverse (41) and represents the general population in terms of demographics (43) and prevalence of certain mental health problems (42).

Data for the present study were collected as part of a larger study developing a novel measure assessing risky behaviors among individuals with stressful life experiences. Participants 18 years of age and older were screened for the larger study based upon three inclusionary criteria: (1) living in North America; (2) working knowledge of the English language; and (3) experience of a traumatic experience (TE) screened with the Criterion A question of the Primary Care PTSD Screen (44). Participants who met eligibility criteria provided informed consent and completed the survey on Qualtrics. Participants were compensated $1.25 for study participation. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at a U.S. university.

Exclusions and Missing Data

Of the obtained 891 responses, duplicate responses were excluded for 18 participants who attempted to answer the questionnaire multiple times (47 responses; remaining n = 844). We then excluded 150 participants not meeting one or more inclusionary criteria (remaining n = 694), 122 participants (remaining n = 572) who failed to pass any of four validity checks interspersed in the study to ensure attentive responding (three items; e.g., participants being asked to rate “I have never brushed my teeth” on a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) and comprehension (one item, asking participants to click on a little blue circle rather than on the scale with items labelled from 1 to 5) (45–47), and 97 participants for missing data on all measures (remaining n = 475). Using data obtained from the Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) (48), we excluded 11 participants who either did not endorse a TE, or did not identify their index (i.e., most distressing) TE (remaining n = 464). Finally, we excluded 69 participants missing more than 30% item-level data on any primary variable of interest (see Measures).

The final MTurk sample included 395 participants. See Table 1 for demographic data and prevalence rates of index TEs. Average age of participants was 35.55 years (SD = 11.09), and 222 were female (56.20%). Approximately one-third of participants reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of depression (n = 130, 32.9%), based on a cut-off score of 10 or greater (49). Approximately one-quarter of participants reported alcohol consumption consistent with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (n = 96, 24.3%), based on a cutoff score of 5 or greater (50). The most common index TEs were: transportation accidents (16.8%), natural disasters (13.5%), and sexual assault (12.4%).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| M (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.55 (11.07) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 167 (42.3%) | |

| Female | 222 (56.2%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 53 (13.4%) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 336 (85.1%) | |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian/White | 303 (76.7%) | |

| African American/Black | 39 (9.9%) | |

| Asian | 42 (10.6%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 19 (4.8%) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 284 (71.9%) | |

| Part-time | 62 (15.7%) | |

| Unemployed | 29 (7.3%) | |

| Retired | 13 (3.3%) | |

| Unemployed Student | 7 (1.8%) | |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Not dating | 64 (16.2%) | |

| Casually dating | 29 (7.3%) | |

| Seriously dating | 97 (24.6%) | |

| Married | 174 (44.1%) | |

| Divorced | 18 (4.6%) | |

| Separated | 6 (1.5%) | |

| Widowed | 7 (1.8%) | |

| Index Traumatic Events | ||

| Natural disaster | 53 (13.5%) | |

| Fire or explosion | 20 (5.1%) | |

| Transportation accident | 66 (16.8%) | |

| Serious accident at work, home, or during recreational activity | 13 (3.3%) | |

| Exposure to toxic substance | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Physical assault | 33 (8.4%) | |

| Assault with a weapon | 11 (2.8%) | |

| Sexual assault | 49 (12.4%) | |

| Other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experience | 10 (2.5%) | |

| Combat or exposure to a war-zone | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Captivity | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Life-threatening illness or injury | 30 (7.6%) | |

| Severe human suffering | 5 (1.3%) | |

| Sudden violent death | 26 (6.6%) | |

| Sudden accidental death | 28 (7.1%) | |

| Serious injury, harm, or death you caused to someone else | 7 (1.8%) | |

| Any other very stressful event or experience | 22 (5.6%) | |

Measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (51).

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure assessing depression symptoms over the past two weeks. The four response options range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (49). Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptom severity. The PHQ-9 has good psychometrics (49). Cronbach’s α in the current study was .91 for the PHQ-9.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive (DERS-P) (52).

The DERS-P is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses difficulties regulating positive emotions across three subscales: nonacceptance of positive emotions (DERS-P Accept), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions (DERS-P Goals), and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions (DERS-P Impulse). Higher scores on the DERS-P subscales indicate greater difficulties regulating positive emotions. Participants rate each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). The dimensions of the DERS-P have good psychometrics (52). Cronbach’s αs in the current sample were .93, .88, and .95 for the DERS-P Accept, DERS-P Goals, and DERS-P Impulse, respectively.

Alcohol Use and Disorders Identification Test Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) (50).

The AUDIT-C is a 3-item self-report measure assessing heavy drinking and active alcohol use disorder. Participants rate each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (Item 1 [frequency]: 0 [never] to 4 [daily or more times a week]; Item 2 [consumption]: 0 [1 or 2] to 4 [10 or more]; Item 3 [binge drinking]: 0 [Never] to 4 [daily/almost daily]). Higher scores indicate greater alcohol use. The AUDIT-C has good psychometrics (50). Cronbach’s α in this study was .74 for the AUDIT-C.

Demographic information.

Information regarding age, gender, ethnicity, race, income, educational level, employment status, ethnicity, and relationship status was obtained.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24.0 (53). In line with recommendations by Tabachnick and Fidell (54), relevant study variables were assessed for assumptions of normality. Next, Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted to evaluate the relations among depression symptom severity (PHQ-9), the three subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions (DERS-P), and risky alcohol use (AUDIT-C). Finally, to examine whether the subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions explain the relation between depressive symptom severity and risky alcohol use, we conducted indirect effect analyses (55) with the PROCESS SPSS macro (56). PROCESS uses ordinary least squares regression and bootstrapping methodology, which confers more statistical power than standard approaches and does not rely on distributional assumptions. The bootstrap method was used to estimate the standard errors of parameter estimates and the bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effects (55, 57). The effect is significant if the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero (55). In this study, 5,000 bootstrap samples were used to derive estimates of the indirect effect.

Results

Pearson-product moment correlations among depression symptom severity, subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use are presented in Table 2. Depression symptom severity was significantly positively associated with each of the subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions as well as risky alcohol use. Each of the subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions were significantly positively related to risky alcohol use.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data and Intercorrelations among Variables of Interest

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | 1.00 | .52** | .45** | .46** | .18** | 7.72 (6.47) |

| 2. DERS-P Accept | 1.00 | .79** | .92** | .22** | 6.12 (3.82) | |

| 3. DERS-P Goals | 1.00 | .83** | .14* | 6.52 (3.56) | ||

| 4. DERS-P Impulse | 1.00 | .22** | 7.54 (4.58) | |||

| 5. Risky Alcohol Use | 1.00 | 3.09 (2.56) |

Note: DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive.

p <.01.

p < .001.

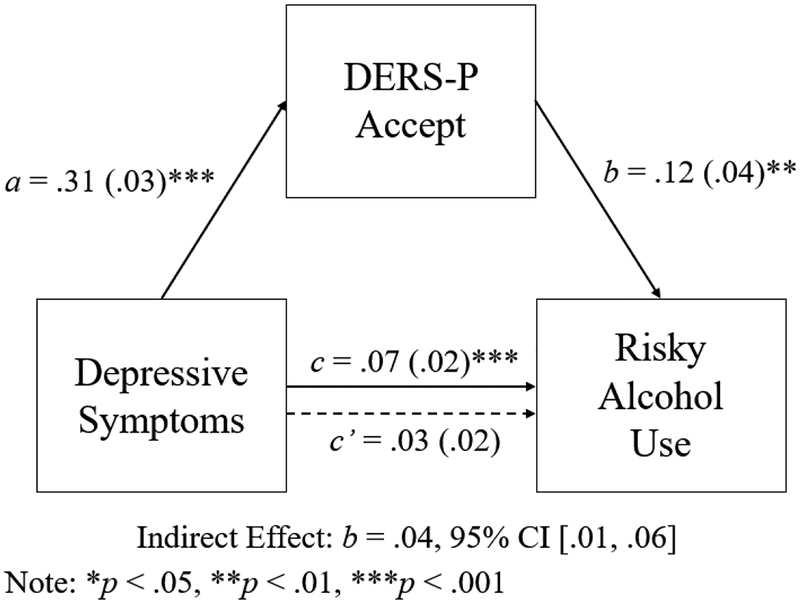

Next, separate models were conducted to examine whether the subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions accounted for the relation between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use. The model testing the role of nonacceptance of positive emotions in the relation between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use is shown in Figure 1. The association between depression symptom severity and nonacceptance of positive emotions was significant, b = .31, SE = .03, t = 12.00, p < .001, as was the association between nonacceptance of positive emotions and risky alcohol use, b = .12, SE = .04, t = 3.13, p = .002. Furthermore, the indirect effect of depression symptom severity on risky alcohol use through the pathway of nonacceptance of positive emotions was also significant, b = .04, SE = .01, p <.05, 95% CI [.01, .06]. Notably, the direct effect linking depression symptom severity with risky alcohol use was not significant after controlling for nonacceptance of positive emotions, b = .03, SE = .02, t = 1.37, p = .17.

Figure 1.

Summary of Analyses Explicating the Role of Nonacceptance of Positive Emotions in the Relation between Depression Symptom Severity and Risky Alcohol Use

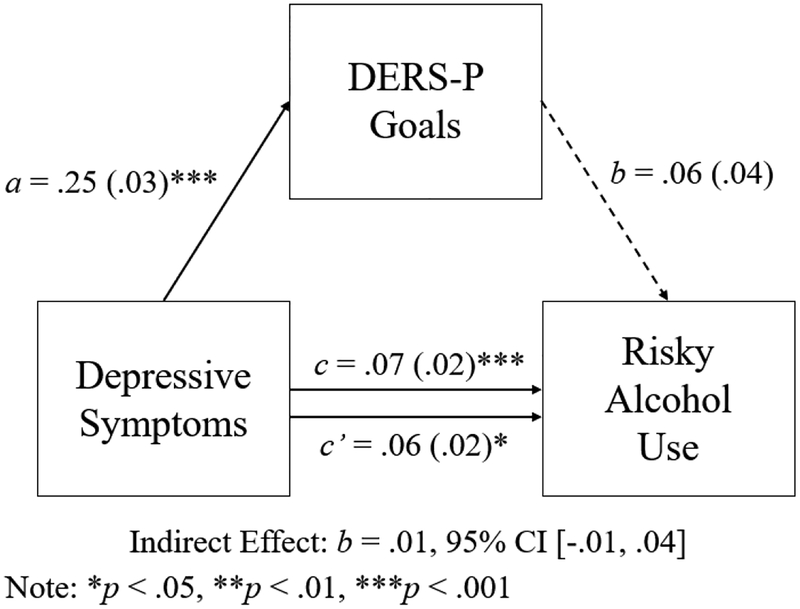

The model explicating the role of difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions in the relation between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use was significant is shown in Figure 2. While the association between depressive symptom severity and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions was significant, b = .25, SE = .03, t = 9.87, p < .001, the association between difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions and risky alcohol use was nonsignificant, b = .06, SE = .04, t = 1.39, p = .17. Additionally, the indirect effect of depression symptom severity on risky alcohol use through the pathway of difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions was non-significant, b = .01, SE = .01, p < .05, 95% CI [−.01, .04], and the direct effect linking depression symptom severity with risky alcohol use when controlling for difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions was significant, b = .06, SE = .02, t = 2.55, p = .01. These findings suggest that difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions did not fully account for the association between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use.

Figure 2.

Summary of Analyses Explicating the Role of Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviors when Experiencing Positive Emotions in the Relation between Depression Symptom Severity and Risky Alcohol Use

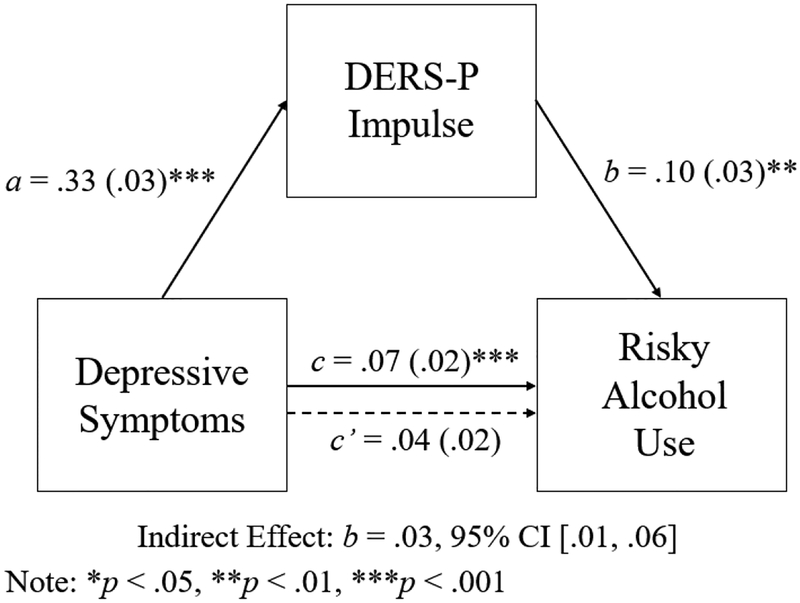

Finally, the model explicating the role of difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions in the relation between depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use is shown in Figure 3. The association between depression symptom severity and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions was significant, b = .33, SE = .03, t = 10.06, p < .001, as was the association between difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions and risky alcohol use, b = .10, SE = .03, t = 3.25, p = .001. Furthermore, the indirect effect of depression symptom severity on risky alcohol use through the pathway of difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions was also significant, b = .03, SE = .01, p < .05, 95% CI [.01, .06]. Notably, the direct effect linking depression symptom severity with risky alcohol use was not significant after controlling for difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions, b = .04, SE = .02, t = 1.72, p = .09.

Figure 3.

Summary of Analyses Explicating the Role of Difficulties Controlling Impulsive Behaviors When Experiencing Positive Emotions in the Relation between Depression Symptom Severity and Risky Alcohol Use

Discussion

An extensive body of literature has demonstrated the high co-occurrence of depression and risky alcohol use (9, 10). Extending extant work, the goal of the present study was to better understand why depression symptom severity is associated with risky alcohol use. Specifically, we examined the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in this association. Difficulties regulating positive emotions has been conceptualized as containing three different aspects including nonacceptance of positive emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions, and difficulties controlling impulsive behavior when experiencing positive emotions (25). As expected, depression symptom severity, subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use were significantly positively correlated at the bivariate level. Further, two subscales of difficulties regulating positive emotions – nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions – were found to account for the relation of depression symptom severity to risky alcohol use.

These findings provide support for the relevance of nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions in the relation between depression and risky alcohol use. Perhaps nonacceptance of positive emotion increases distress and efforts taken to avoid such emotions (58), in turn, increases risk for engaging in maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (18), including risky alcohol use. On the other hand, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions is closely associated with both inhibitory dyscontrol and impulsivity (24), both of which have been linked to risky alcohol use (59, 60). One reason why individuals with depression may be non-accepting of positive emotions is that they may be more likely to experience some secondary negative emotional state in response to stimuli that are typically positive, and therefore may develop a fear of positive emotions over time (32). These individuals may then choose to use alcohol to distract from positive emotions given their increased tendency to suppress these emotional experiences (33).

As expected, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions were significantly positively associated with depression symptom severity. Indeed, one symptom of depression is “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness” (61), which may interfere with goal-directed behavior by diminishing one’s ability to maintain focus on engagement in goal-directed behaviors. Additionally, the negative ruminative style characteristic of depression may lead to diminished motivation to pursue one’s goals as a result of reduced expectancies around success (62). This aligns well with behavioral theories of depression, which state that the onset and course of depression stem from a decrease in engagement in goal-directed behaviors or other positively reinforcing behaviors (63, 64). Further, broadly speaking, the ability to pursue value-consistent, goal-directed behavior would suggest a decreased likelihood of risky alcohol use, as this behavior is generally inconsistent with one’s values and long-term goals. However, while associated with depression symptom severity at the bivariate level, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions were not found to explain the association of depression symptom severity to risky alcohol use. Given this unexpected finding, it would be important for future studies to confirm this finding as well as to explore factors that influence the strength and direction (i.e., moderators) of the relations among depression symptom severity, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions, and risky alcohol use. For instance, it may be that alcohol use is consistent with the goals (e.g., social, pleasure) of some individuals with depression, which may explain why this dimension of difficulties regulating positive emotions was not found to account for the depression symptom severity-alcohol use association.

The findings of the current study should be considered within the context of several limitations. First, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of this data precludes our ability to examine the exact nature and direction of the relations of interest; our findings support examining these relations prospectively within a longitudinal framework. Further, these findings are based on self-report measures of depression symptom severity, difficulties regulating positive emotions, and risky alcohol use. It may be that individuals have poor insight into their emotional experiences or that retrospective reports of depression symptom severity and risky alcohol use were over- or under-inflated. In addition, it warrants mention that the conceptualization of emotion regulation underlying the DERS-P (17, 25, 65) differs from other frameworks of emotion regulation, such as those that (a) equate emotion regulation with temperamental characteristics of emotional intensity/reactivity (66), (b) define emotion regulation as control of emotions and reduction in emotional arousal (67), and (c) classify specific emotion regulation strategies as either adaptive or maladaptive (68, 69). Future research would benefit from exploring the various aspects of emotion regulation in relation to depression symptom severity, risky alcohol use, and their relation. Moreover, given that we examined only depression severity as a predictor of risky alcohol use in trauma-exposed individuals, generalizability of results to other populations (e.g., clinical) may be limited, and PTSD symptom severity (which is quite relevant to trauma-exposed individuals) may also be associated with risky alcohol use through difficulties regulating positive emotions. Indeed, one prior study (70) found that PTSD symptoms were indirectly related to risky behavior through positive urgency among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence (83% of whom reported problematic alcohol use). Notably, however, while it is possible that our results may not directly generalize to clinical samples, it is remains important to examine these relations within non-clinical populations, which have important strengths. For instance, non-clinical samples allow researchers to identify vulnerabilities to the initial development of clinical phenomena (71), whereas research using clinical samples may only tap into processes and characteristics that maintain or exacerbate the course of a disorder. Further, non-clinical samples exhibit greater variability in clinical outcomes compared to clinical samples (which are generally more severe) (72), suggesting that non-clinical samples may capture a larger proportion of the target population. It is for these reasons that researchers have argued that the scientific study of incidence, development, and risk for clinical disorders cannot rely solely on clinical samples (73). Finally, while the MTurk recruitment platform is a notable strength of our study (41–43), collecting data via the internet using an online format has disadvantages that may limit generalizability of results, such as sample biases (because of self-selection) and lack of control over the research environment (e.g., no opportunity to clarify questions, distractions) (74). Thus, future research that integrates other data collection methods (e.g., interviewing, focus groups) is warranted.

Despite these limitations, results of the current study extend our understanding of the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in depression symptom severity, risky alcohol use, and their relation, and thus have important implications. First, our findings suggest that models of emotion regulation should incorporate dysfunction of positive emotional experiences, particularly as they relate to clinically-relevant outcomes such as depression and risky alcohol use. Second, results highlight the potential utility of assessing difficulties regulating positive emotions among individuals diagnosed with depression as a means of identifying those at risk for problematic alcohol use. Finally, the findings of our study suggest the potential importance of addressing difficulties regulating positive emotions in interventions aimed at reducing alcohol use among individuals with depression, specifically skills for improving nonacceptance of positive emotions (e.g., mindfulness or acceptance-based skills) and controlling impulsive behaviors in the context of positive emotions (e.g., distress tolerance skills). Overall, assessing and addressing positive emotion-based dysregulation in trauma-exposed samples experiencing concurrent depression and risky alcohol use is warranted in clinical work.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Work on this paper by the second author (NHW) was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants K23DA039327 and L30DA038349.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None.

References

- 1.Yoon Y-H, Chen CM, Yi H. Surveillance Report# 100: Liver Cirrhosis Mortality in the United States: National, State, and Regional Trends, 2000–2011. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Bethesda, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Jama. 2004;291(10):1238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SAMHSA. Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies: Findings from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):223–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hull JG, Bond CF. Social and behavioral consequences of alcohol consumption and expectancy: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin. 1986;99(3):347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, supplement. 2002(14):91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2006;67(1):169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, Lewinsohn PM. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2014;55(3):526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasin DS, Tsai WY, Endicott J, Mueller TI, Coryell W, Keller M. The effects of major depression on alcoholism. The American Journal on Addictions. 1996;5(2):144–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Chacko Y. Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82(3):194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Trim R, Nurnberger JI, et al. A comparison of factors associated with substance-induced versus independent depressions. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2007;68(6):805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Smit JH, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT, et al. Comorbidity and risk indicators for alcohol use disorders among persons with anxiety and/or depressive disorders: findings from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Journal of affective disorders. 2011;131(1):233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD. Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. The American journal of psychiatry. 1995;152(3):358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments. Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. 2010:107–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berking M, Margraf M, Ebert D, Wupperman P, Hofmann SG, Junghanns K. Deficits in emotion-regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive–behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2011;79(3):307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berking M, Wirtz CM, Svaldi J, Hofmann SG. Emotion regulation predicts symptoms of depression over five years. Behaviour research and therapy. 2014;57:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joormann J, Stanton CH. Examining emotion regulation in depression: a review and future directions. Behaviour research and therapy. 2016;86:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, Williams TJ. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: Associations with emotion regulation difficulties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(2):125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM. Emotion dysregulation and coping drinking motives in college women. American journal of health behavior. 2014;38(4):553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and individual differences. 2007;43(4):839–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss NH, Gratz KL, Lavender JM. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: the DERS-positive. Behavior modification. 2015;39(3):431–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss NH, Forkus SR, Contractor AA, Schick MR. Difficulties regulating positive emotions and alcohol and drug misuse: A path analysis. Addictive behaviors. 2018;84:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss NH, Risi MM, Bold KW, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL. Daily relationship between positive affect and drinking to cope: the moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1991;100(3):316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1998;107(2):179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond: Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DePierro J, D’Andrea W, Frewen P, Todman M. Alterations in Positive Affect: Relationship to Symptoms, Traumatic Experiences, and Affect Ratings. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams KE, Chambless DL, Ahrens A. Are emotions frightening? An extension of the fear of fear construct. Behaviour research and therapy. 1997;35(3):239–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beblo T, Fernando S, Klocke S, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, Driessen M. Increased suppression of negative and positive emotions in major depression. Journal of affective disorders. 2012;141(2):474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karyadi KA, King KM. Urgency and negative emotions: Evidence for moderation on negative alcohol consequences. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51(5):635–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forbes EE, Shaw DS, Dahl RE. Alterations in reward-related decision making in boys with recent and future depression. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61(5):633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological review. 2004;111(1):33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreisbach G, Goschke T. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: Reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30:343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forgas JP. Mood and the perception of unusual people: Affective asymmetry in memory and social judgments. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1992;22:531–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis. 2004;24:311–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss NH, Darosh AG, Contractor AA, Forkus SR, Dixon-Gordon KL, Sullivan TP. Heterogeneity in emotion regulation difficulties among women victims of domestic violence: A latent profile analysis. Journal of affective disorders. 2018;239:192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shapiro DN, Chandler J, Mueller PA. Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:213–20. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mischra S, Carleton N. Use of online crowdsourcing platforms for gambling research. International Gambling Studies. 2017;17:125–43. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prins A, Bovin MJ, Kimerling R, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, Pless Kaiser A, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5). 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas KA, Clifford S. Validity and mechanical turk: An assessment of exclusion methods and interactive experiments. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;77:184–97. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meade AW, Craig SB. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:437–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oppenheimer DM, Meyvis T, Davidenko N. Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:867–72. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, Keane TM. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at wwwptsdvagov. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ 9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA, for the Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C). An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss NH, Gratz KL, Lavender J. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification. 2015;39:431–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corporation IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics, 5th Needham Height, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers. 2004;36(4):717–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. University of Kansas, KS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods. 2002;7(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(6):1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201(3):315–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological assessment. 2007;19(1):107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

- 62.Hadley SA, MacLeod AK. Conditional goal-setting, personal goals and hopelessness about the future. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24(7):1191–8. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferster CB. A functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist. 1974;28:857–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S. Behavioral activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: science and practice. 2001;8(3):255–70. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments In: Baer RA, editor. Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2010. p. 105–33. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Archives of general psychiatry. 1998;55(10):941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeman J, Garber J. Display rules for anger, sadness, and pain: It depends on who is watching. Child development. 1996;67(3):957–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler EA, Egloff B, Wlhelm FH, Smith NC, Erickson EA, Gross JJ. The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion. 2003;3(1):48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Review of general psychology. 1998;2(3):271. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky behaviors among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence: The influence of negative and positive urgency. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;155:147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tull MT, Bornovalova MA, Patterson R, Hopko DR, Lejuez C. Analogue research Handbook of research methods in abnormal and clinical psychology. 2008:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hasking PA, Oei TPS. Confirmatory factor analysis of the COPE questionnaire on community drinkers and an alcohol-dependent sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(5):631–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2002;70(6):1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kraut R, Olson J, Banaji M, Bruckman A, Cohen J, Couper M. Psychological research online: Report of Board of Scientific Affairs’ Advisory Group on the Conduct of Research on the Internet. American Psychologist. 2004;59:105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]