Abstract

In this study we examined whether the action of simvastatin affects re-differentiation of passaged chondrocytes and if so, whether this was mediated via changes in cholesterol or cholesterol intermediates. Bovine articular chondrocytes, of varying passage number, human knee chondrocytes and rat chondrosarcoma chondrocytes were treated with simvastatin and examined for changes in mRNA and protein expression of markers of the chondrocyte phenotype as well as changes in cell shape, proliferation and proteoglycan production. In all three models, while still in monolayer culture, simvastatin treatment alone promoted changes in phenotype and morphology indicative of re-differentiation most prominent being an increase in SOX9 mRNA and protein expression. In passaged bovine chondrocytes, simvastatin stimulated the expression of SOX9, ACAN, BMP2 and inhibited the expression of COL1 and α-smooth muscle actin. However, the co-treatment of chondrocytes with simvastatin plus exogenous cholesterol—conditions that had previously reversed the inhibition on CD44 shedding, did not alter the effects of simvastatin on re-differentiation. However, co-treatment of chondrocytes with simvastatin together with other pathway intermediates, mevalonate, geranylgeranylpyrophosphate and to a lesser extent, farnesylpyrophosphate, blocked the pro-differentiation effects of simvastatin. Treatment with simvastatin stimulated expression of SOX9 and COL2a and enhanced SOX9 protein in human OA chondrocytes. The co-treatment of OA chondrocytes with mevalonate or geranylgeranylpyrophosphate, but not cholesterol, blocked the simvastatin effects. These results lead us to conclude that the blocking of critical protein prenylation events is required for the positive effects of simvastatin on the re-differentiation of chondrocytes.

Keywords: Chondrocyte, Simvastatin, Aggrecan, SOX9, Osteoarthritis, Prenylation

Introduction

Advancement of cartilage repair requires further study of the processes involved in reestablishing and maintaining the chondrocyte phenotype [1–6]. Cytokine-activated chondrocytes, de-differentiated chondrocytes (generated by multiple passages in cell culture) [2, 7] and the rat chondrosarcoma (RCS) cell line [8–10] all exhibit modulated phenotypic properties similar to osteoarthritic (OA) chondrocytes. This modulation of phenotype can be often reversed by 3-D culture of chondrocytes in alginate beads resulting in increased aggrecan production and decreased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity [7]. In a previous study we observed that the passage and dedifferentiation of chondrocytes resulted in enhanced shedding of the hyaluronan receptor, CD44 [2]. This shedding was the result of extracellular, cell surface cleavage of the CD44 extracellular domain followed by a γ-secretase-mediated release of the CD44 intracellular domain fragment into the cytoplasm. Interestingly, direct extracts from human OA cartilage also contain an abundance of similar CD44 fragments suggesting this activity occurs in vivo [2]. In subsequent studies, we identified ADAM10 as the primary sheddase responsible for the initial CD44 cleavage in chondrocytes [7]. Moreover, we determined that the activity of ADAM10 cleavage required the presence of lipid raft environment in the chondrocyte plasma membrane. Treatment of chondrocytes with simvastatin disrupted lipid rafts and blocked CD44 cleavage—a process that could be rescued by the re-introduction of soluble cholesterol or mevalonic acid. Interestingly, the re-introduction of another intermediate in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway namely, farnesyl-pyrophosphate, FPP (but not geranylgeranyl-pyrophosphate, GGPP) also reversed the inhibition of CD44 cleavage due to simvastatin suggesting that changes in protein prenylation may also be involved in this mechanism. Given the close association between enhanced CD44 cleavage and the altered phenotype of OA or de-differentiated chondrocytes, we designed experiments to test whether modulation of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway effected more than just ADAM10 but additionally, the overall phenotype associated with its activity. Our analysis of the chondrocyte phenotype included elements of the complex extracellular matrix of articular cartilage; the proteoglycan aggrecan (ACAN), the hyaluronan synthase (HAS2) and type II collagen (COL2A). Dedifferentiation of chondrocytes in cell culture commonly results in decreased expressed of type II collagen coupled with an increase in type I collagen (COL1) [11] [12]. The SOX9 protein is considered a master regulator of the chondrocyte phenotype including the control the expression of aggrecan and type II collagen expression; SOX9 expression is reduced as chondrocytes are passaged [13].

Methods

Cell Culture—

Articular chondrocytes were isolated from full-thickness slices of cartilage from bovine metacarpophalangeal joints of 18–24-month-old steers or, from normal-looking articular cartilage regions of human OA cartilage obtained following knee replacement surgery, both obtained with institutional approval and as described previously [14]. The human cartilage samples were from patients ranging in age from 47 to 75 years. Bovine normal and human OA chondrocytes were isolated by sequential digestion of cartilage slices with Pronase (EMD Biosciences) and collagenase P (Roche) as described. Primary bovine or human OA chondrocytes (P0) were typically plated as high-density monolayers (2.0 × 106 cells/cm2) and cultured in DMEM:Ham’s F12 nutrient media mixture (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and1% L-glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin. In other experiments, P0 bovine chondrocytes were plated into culture flasks at a low density of 5×104 cells/cm2. When these primary P0 chondrocyte monolayers reached confluence, the cells were detached by treatment with trypsin–EDTA (0.25% trypsin/2.21 mM EDTA) and then re-plated as a new monolayer at 5×104 cells/cm2 (passage 1; P1). The bovine chondrocytes were expanded from P0 to P5. The rat chondrosarcoma cell line (RCS-o) is a continuous long-term culture line derived from the Swarm rat chondrosarcoma tumor [15]. The RCS-o cell line in the Knudson laboratories was a gift of Dr. James H. Kimura and is an early, original clone of cells that eventually became known as long-term culture RCS [16]. The RCS-o chondrocytes were cultured as high density monolayers like the bovine and human chondrocytes (2.0 × 106 cells/cm2) but in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% L-glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin.

Treatment of Cells—

For most experiments, bovine, human OA or RCS chondrocytes were plated in 12 well plates at high density (2.0 × 106 cells/cm2) and after an initial 48 h recovery, treated with 5 μM simvastatin (Sim) in DMEM + 10% FBS or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) for varying times. In other experiments, simvastatin-treated cultures were co-treated with 500 μM mevalonic acid (MVA), 500 μM cholesterol (CHOL), 10 μM farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) or 10 μM geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). In preliminary studies, P0 bovine articular chondrocytes and cells expanded by P1 to P5 were examined. P1 cells often differed little from P0 and did not exhibit markers of de-differentiation while P4, P5 cells become increasingly senescent (data not shown). Therefore, most of the data reported herein were obtained using P0 bovine chondrocytes and P2 and P3 expanded cells. Also in preliminary studies, the effects of 0.2, 1.0, 5.0 and 10.0 μM simvastatin on P2 cells were examined. The addition of simvastatin at 5.0 μM provided a consistently optimal stimulation of Sox9, Acan and Col2a mRNA as compared to control cells with little evidence of cell toxicity and was thus chosen for all experiments (data not shown). To test cell viability; the fluorescent live/dead cells assay (Invitrogen/Thermo-Fisher) was used. Red (dead) and green (viable) cells were counted in multiple fields of >200 cells. Time course studies determined that 4 days of treatment with 5.0 μM simvastatin was sufficient to observe these changes in bovine and human chondrocytes (data not shown). Studies with RCS-o chondrocytes were examined at 48 h because of overgrowth at longer time points.

DMMB Staining of Monolayers—

Chondrocytes were plated into either 12-well plates or chamber slides at varying densities. Following overnight attachment, cells were treated without or with 5.0 μM simvastatin treatment for 4 days. In some cultures, 10 units/ml Streptomyces hyaluronidase was added directly to the culture medium for 2 hours prior to fixation and staining. Cell medium was removed, the cells washed with PBS followed by 15 min treatment with 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature. The cells were washed again with PBS and then incubated overnight in a solution of dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) in the dark with no rocking. The DMMB was prepared as described previously [10, 17, 18]. Cells were examined in plates using a Nikon TE2000 inverted phase-contrast microscope and images were captured digitally in real time using a Retiga 2000R digital camera (QImaging).

Growth curves—

Bovine P0 chondrocytes or P3 cells were plated at 20,000 cells/well in a 12 well plate. For each condition, six replicate wells were plated. Cells in one well were counted in duplicate each day using the Countess™ automated cell counter (Invitrogen) and cell number recorded over the course of 7 days.

Real time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)—

Total RNA was isolated from the bovine, human or RCS chondrocyte cultures according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the use of TRIzolR reagent (Thermo-Fisher). Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). Quantitative, real time qRT-PCR was performed using Sso-Advanced SYBR-Green Supermix (BioRad) and amplified on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) to obtain cycle threshold (Ct) values for target and internal reference cDNA levels. Relative changes in copy numbers was determined by ΔΔCt [14]. Relative mRNA expression data shown represent the average ± SD of 3 independent experiments (performed at different times) each assayed in duplicate. GAPDH was used as the reference gene for normalization of data. Primers used were as described in our previous studies [2, 8, 14] unless otherwise specified. The bovine-specific primer sequences are follows: ACAN, forward (5’-AAATATCACTGAGGGTGAA GCCCG-3’) and reverse (5’-ACTTCAGGGACAAACGTGAAAGGC-3’); BMP2, forward (5′-CGCAGCTTCCATCACGAA-3′) and reverse (5′-AGAAGAATCGCCGGGTTGTT-3′); COL1A2 [19]: forward (5′-ACATGCCGAGACTTGAGACTCA-3′) and reverse (5′-GCATCCATAGTACATCCT TGGTTAGG-3′); COL2A1 [19]: forward (5′-AGCAGGTTCACATATACCGTTCTG-3′) and reverse (5′-CGATCATAGTCTTGCCCCACTT-3′); GAPDH, forward (5′-ATTCTGGCAAAGTGGACATCGTCG-3′) and reverse (5′ATGGCCTTTCCATTGATGACGAGC-3′); HAS-2, forward (5′-GAGGACGACTTTATGACCA AGAGC-3′) and reverse (5′-TAAG CAGCTGTGATTCCAAGGAGG-3′; SOX9: forward (5′-AAGAAGGAGAGCGAGGAGGACAA GTT-3′) and reverse (5′-TTGTTCTTGCTCG AGCCGTTGA-3′). The human-specific primer sequences are follows: ACAN, forward (5’TCTGTAACCCAGGCTCCAAC-3’) and reverse (5’-CTGGCAAAATCCCCACTAAA-3’); COL2A1 [20], forward (5’-GGCAATAGCAGGTTCACGT ACA-3’) and reverse (5’CGATAACAGTCTTGCCCCACTT-3’); SOX9, forward (5′-CACACAGC TCACTCGACCTTG-3′) and reverse (5′-TTCGGTTATTTTTAGGATCATCTCG-3′); GAPDH, forward (5’GAATTTGGCTACAGCAACAGG-3’) and reverse (5’AGTGAGGGTCTCTCTCTTCC-3’). The rat-specific primer sequences are follows: SOX9, forward (5′-CATCAAGACGGAGCAAC TGA-3′) and reverse (5′-TGTAGTGCGGAAGGTTGAAG-3′); and GAPDH, forward (5′GATACTGAGAGCAAGAGAGAGG-3′) and reverse (5′-TCTGGGATGGAATTGTGAGG-3′).

Western Blotting—

Total protein was extracted using Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equivalent protein concentrations were loaded into NuPAGE® Novex® 4–12% gradient sodium electrophoresis mini gels (Invitrogen). Following electrophoresis, proteins within the acrylamide gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and then blocked in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat dry milk (TBS-T-NFDM) for 1 h. Immunoblots were incubated overnight with primary antibody in TBS-T-NFDM at 4°C, rinsed three times in TBS-T, and incubated with secondary antibody in TBS-T-NFDM for 1 h at room temperature. Detection of immunoreactive bands was performed using chemiluminescence (Novex ECL, Invitrogen). In some cases, the blots were stripped using Restore Plus Western Stripping Buffer [14] for 30 min at room temperature and re-probed using another primary antibody. Antibodies used include SOX9 (D8G8H, rabbit monoclonal, Cell Signaling); α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, A5528, mouse monoclonal, Sigma); GAPDH (0411, mouse monoclonal IgG, sc-47724, Santa Cruz) and; β-actin (A1978, clone AC-15, Sigma) as well as secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (SA1200), and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (SA1–100) both from ThermoFisher. Detection was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Novex ECL; Invitrogen, West Pico; Thermo Fisher Science). The same anti-Sox9 antibody was used for immunofluorescence studies at a 1:400 dilution. Developed x-ray films were imaged and digitized using a BioRad GelDoc with ImageLab software. Pixel intensities for SOX9 bands or αSMA bands were used for quantification after normalization to loading control bands (β-ACTIN or GAPDH). All other experimental details not mentioned here are described in figure legends.

Statistical analysis—

Experiments performed using bovine articular chondrocytes represent at least three independent preparations of cells per experiment. Experiments on human OA chondrocytes were repeated using cells derived from the cartilage of three different osteoarthritic patients. Results are displayed as representative experiments and are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis were performed using Stata version 13 software and statistical differences were assessed using the Student’s t test analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant and noted with an *; P < 0.01 was noted with ** or, P value was otherwise stated.

Results

Effect of simvastatin on bovine articular chondrocytes.

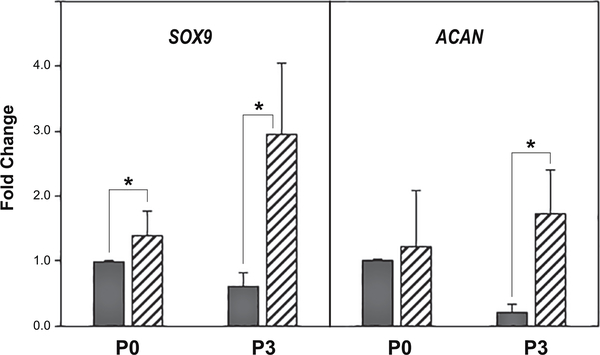

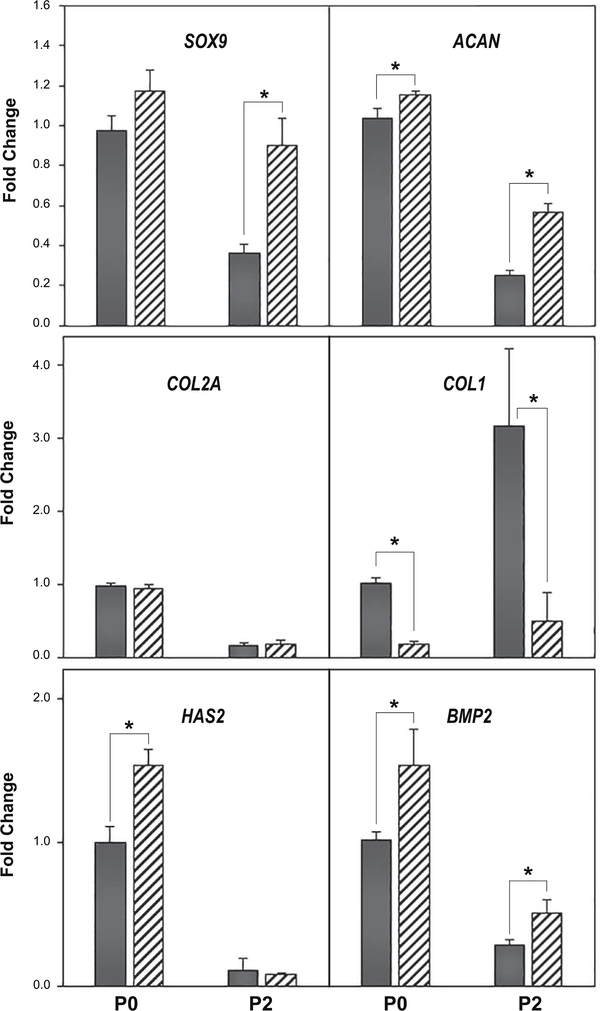

We first examined primary (P0) versus passaged (P1 – P5) articular chondrocytes obtained from bovine metacarpophalangeal joints as described previously [2]. These cells serve as the traditional model that has been long used by investigators to examine the mechanism of de-differentiation / re-differentiation associated with the chondrocyte phenotype [2, 6, 21]. An example of this is shown in Fig. 1, wherein P3 cells (black bars) exhibit a reduction in both SOX9 and ACAN mRNA as compared to primary P0 bovine chondrocytes. The addition of 5 μM simvastatin for 4 days (hatched bars) resulted in a pronounced recovery of SOX9 and ACAN mRNA in P3 cells; with little-to-no effect of these markers in P0 chondrocytes. A similar effect was observed when P0 and P2 bovine chondrocytes were compared (Fig. 2). P0 chondrocytes exhibited little stimulation of SOX9 or ACAN mRNA following treatment with simvastatin whereas P2 chondrocytes exhibited a more robust response. No change in COL2A mRNA in either P0 or P2 chondrocytes was observed within this time period however, COL1 was diminished. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) have been suggested to work in concert with SOX9 to affect chondrocyte re-differentiation [4]. To determine whether this occurred as an autocrine response, we examined changes in endogenous BMP2 mRNA in our system. As shown in Fig. 2, chondrocyte BMP2 mRNA was enhanced in both P0 and P2 cells following treatment with simvastatin. HAS2 mRNA was also enhanced by simvastatin treatment but only in P0 chondrocytes. These results suggest that simvastatin promotes the maintenance of chondrocyte differentiation.

Figure 1. Effect of simvastatin on SOX9 and aggrecan mRNA expression by primary bovine articular chondrocytes and passage 3 derived cells.

SOX9 and aggrecan (ACAN) mRNA expression in primary (P0) bovine articular chondrocytes or third passage (P3) cells was determined by qRT-PCR analysis. Dark bars depict P0 or P3 vehicle control cells as labeled; hatched bars, the same cells following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin. Panels show the relative mRNA expression data average ± SD (control P0 chondrocytes set to 1.0), of 3 independent experiments (performed at different times) each assayed in duplicate. * P <0.05.

Figure 2. Effect of simvastatin on marker genes indicative of changes in the chondrocyte phenotype.

qRT-PCR analysis was used to determine SOX9, ACAN, COL2A, COL1, HAS2 and BMP2 mRNA expression in P0 and P2 bovine chondrocytes with the vehicle control (dark bars) or the same cells following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin (hatched bars). Panels show the relative mRNA expression data, average ± SD (control P0 chondrocytes set to 1.0), of 3 independent experiments (performed at different times) each assayed in duplicate. * P <0.05.

Simvastatin effects at the protein level in bovine articular chondrocytes.

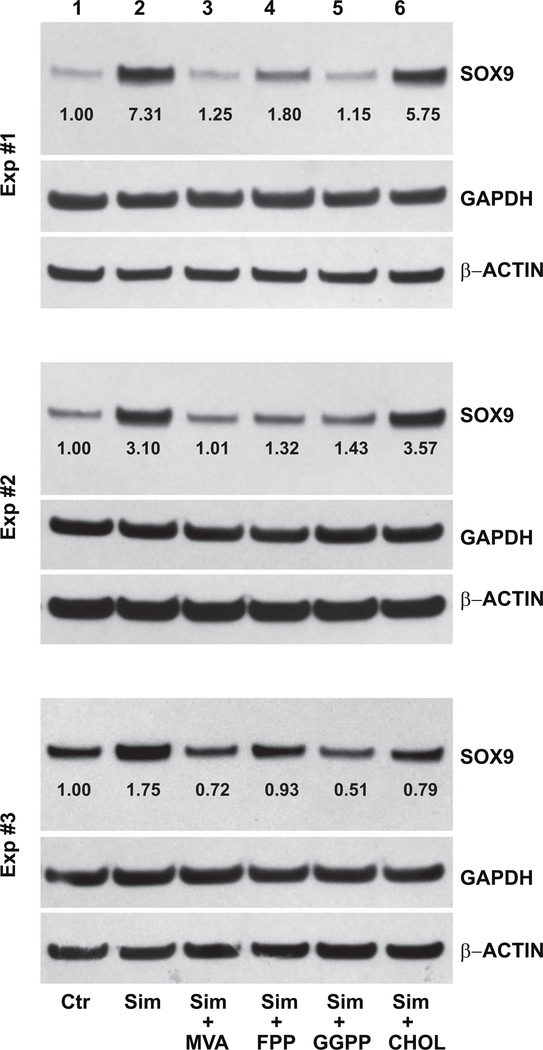

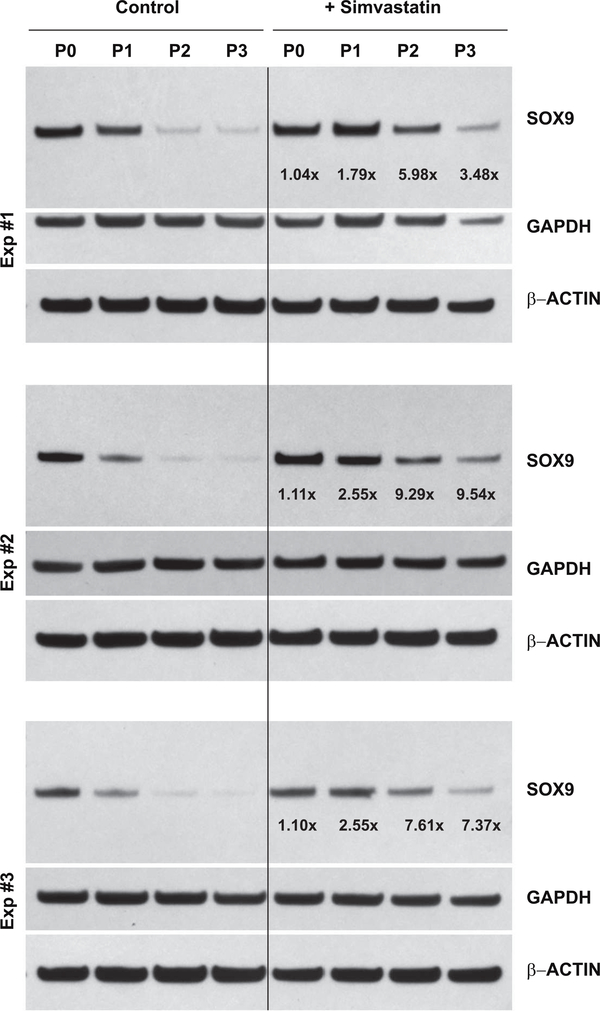

SOX9 is considered a master transcription factor for chondrocyte differentiation, driving changes in expression of ACAN, COL2A and COL1 [13]. The SOX9 protein is synthesized as a single, ~70 kD band that can be readily identified by western blotting. Fig. 3 depicts three independent experiments of SOX9 protein expression by P0 bovine chondrocytes and P1, P2 and P3 cells. Under control, untreated conditions, SOX9 protein accumulation is substantially reduced in even first passage P1 cells as compared to primary P0 chondrocytes. Only faint expression of SOX9 protein is observed in lysates from P2 or P3 cells. After 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin, SOX9 protein accumulation in P1 cells is nearly equivalent with P0 chondrocytes. Moreover, little-to-no increase in SOX9 protein (1.08 ± 0.04-fold increase) between untreated and treated P0 chondrocytes was observed, similar to the effects on SOX9 mRNA shown in Figs. 1 and 2. In all three experiments, P2 and P3 cells displayed a pronounced enhancement of SOX9 protein in response to simvastatin treatment. Only minor differences in lane loading controls (β-ACTIN and GAPDH) were observed. Densitometric analysis of western blots in Figs. 3 and 8 determined an average 5.6 ± 2.8-fold increase in SOX9 protein levels in P3 cells stimulated by simvastatin.

Figure 3. Effect of simvastatin on SOX9 protein accumulation in primary bovine chondrocytes and passaged cells.

Western blot analysis was used to determine changes in SOX9 protein in P0 bovine articular chondrocytes, P1, P2 and P3 cells without (left lanes labeled Control) or following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin (right lanes, labeled +Simvastatin). Following detection of the ~70 kD SOX9 protein (70 kD), the same blots were stripped and reprobed for GAPDH and then a second time for β-actin. Values determined by densitometry show the fold-change in SOX9 band intensity after simvastatin treatment compared to untreated P0, P1, P2 or P3 cells, with values normalized to β-ACTIN in the same lysate. Data from 3 independent experiments (Exp #1, Exp #2 and Exp #3), performed at different times are shown.

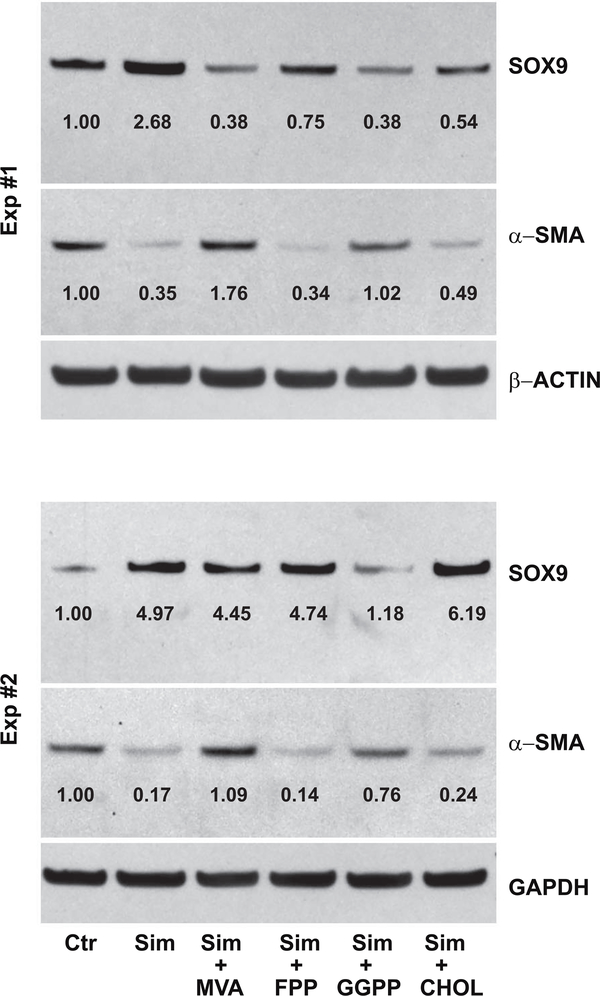

Figure 8. The capacity of cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates to reverse the effects of simvastatin on SOX9 and α-smooth muscle actin protein accumulation in passaged bovine chondrocytes.

Western blot analysis was used to determine changes in SOX9 and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein in P3 cells without (left lanes labeled Control, Ctr) or following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin (right lanes, Sim) in the absence or presence of 500 μM mevalonic acid (MVA), 10 μM farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), 10 μM geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) or 500 μM cholesterol (CHOL) as labeled. Following detection of the ~70 kD SOX9 protein or 42 kD αSMA, the same blots were stripped and reprobed for the reference protein, either β-ACTIN or GAPDH. Values determined by densitometry show the fold-change in SOX9 and α-SMA band intensities after treatments compared to untreated P3 cells (Ctr; set to 1.00) with values normalized to the reference gene protein in the same lysate. Data from 2 independent experiments (Exp #1, Exp #2), performed at different times are shown.

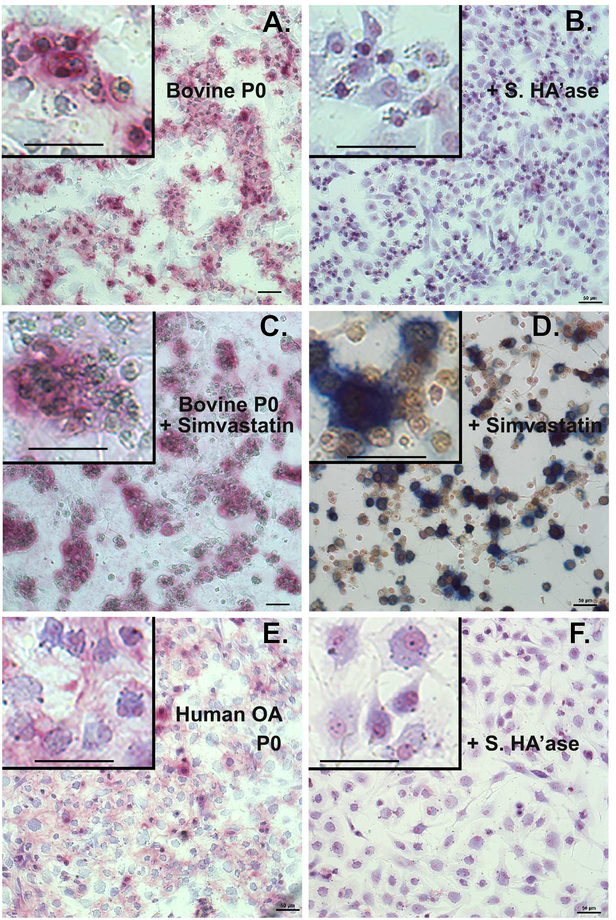

Changes in ACAN mRNA were also observed in response to simvastatin (Figs. 1, 2). However, it is difficult to detect aggrecan core protein by western blotting or capture and observe accumulation of extracellular mature aggrecan in monolayer cultures using traditional staining protocols such as toluidine blue, alcian blue or safranin O. We recently reported the use of dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) as well as Stains-All for selective staining of purified bovine aggrecan within agarose gels following electrophoresis and fixation [10]. Purified aggrecan within the agarose gels stained bright pink with DMMB whereas purified hyaluronan remains undetected. Both aggrecan and hyaluronan were positive to gel staining with Stains-All in agarose gels [10]. We applied these same methods to paraformaldehyde or ethanol fixed monolayer cultures of bovine articular chondrocytes. A representative example of DMMB versus Stains-All staining is shown in Figs. 4C and 4D respectively. As shown in Fig. 4A-4C, P0 bovine articular chondrocytes display a round-to-polygonal cell shape with a blue cytoplasm. Surrounding many of these P0 cells are large patches of pink-staining proteoglycan (Fig. 4A, C). With Stains-All (Fig. 4D) P0 chondrocytes display similar morphology as shown in Fig. 4C but now include a yellow cytoplasm and dark blue patches of deposited proteoglycan. Proteoglycan such as aggrecan or versican are retained at the cell surface via the interaction of their G1 domains with hyaluronan [10, 22]. We have shown previously that treatment of bovine chondrocytes with a hyaluronan-specific hyaluronidase (Streptomyces hyaluronidase) results in the removal of the hyaluronan/aggrecan-rich pericellular matrix [23] as well as the majority of the 35S-labeled proteoglycan [24]. Post-treatment of the P0 bovine or human chondrocytes for 2–4 hours with Streptomyces hyaluronidase resulted in the complete loss of the pink-staining patches of proteoglycan (Fig. 4B, 4F). The addition of 5 μM simvastatin to the P0 chondrocytes resulted in little change in accumulation of aggrecan deposition (Fig. 4C, 4D) as compared to untreated P0 cells (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Proteoglycan accumulation in primary (P0) chondrocyte cultures.

Primary (P0) cultures of bovine articular chondrocytes (panels A-D) or human OA chondrocytes (panels E, F) were treated 4 days without (panels A, B, E and F) or with 5 μM simvastatin (panel C) as labeled, fixed and stained with DMMB (panels A-C, E, F). Parallel cultures of cells shown in panels A and E were post-treated with 10 U/ml Streptomyces hyaluronidase for 3 hours (panels B and F) before fixation and DMMB staining. In panel D, bovine chondrocytes treated with simvastatin were stained with Stains-All. All images are depicted at similar magnification (50 μm bar) and taken under identical condition; minor linear adjustments (Brightness / Contrast) were made to the image [42]. Insets represent digitally enlarged (~3.3x higher) images to better display cellular detail and include 50 μm bar for comparison. Images shown are representative fields of cells grown at 3 different densities per experiment and, except for human OA chondrocytes, are representative of 3–8 independent experiments.

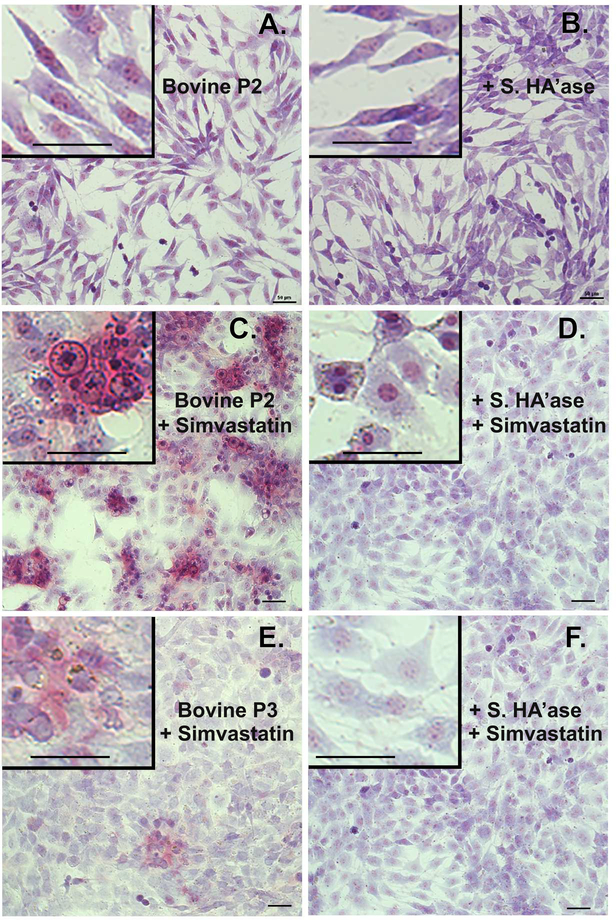

Untreated P2 cells displayed an extended fibroblast-like cell shape with cells overlapping as they reached confluence; no pinkish staining for proteoglycan was detected (Fig. 5A). After 4 days of treatment with simvastatin, the P2 cells became more polygonal in shape with a reduction of long extensions in their cytoplasm (Fig. 5C, D). More importantly, the simvastatin-treated P2 cells now displayed large patches of pink staining proteoglycan (Fig. 5C); proteoglycan that was removed by treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase (Fig. 5D). The morphological changes in P3 chondrocytes were similar to the P2 cells. Untreated P3 cells (not shown), like P2 cells (Fig 5A) displayed a fibroblast-like shape with no proteoglycan accumulation evident whereas P3 cells treated with simvastatin exhibited proteoglycan accumulation (Fig. 5E) but not quite to the extent as P2 cells. Even after post-treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase, simvastatin-treated P3 cells displayed a more cobblestone cell shape (Fig. 5F). The enhanced accumulation of DMMB staining material in P2 and P3 chondrocytes treated with simvastatin suggests that mature aggrecan is now being produced and deposited extracellularly in a fashion similar to proteoglycan deposits of primary P0 bovine articular chondrocytes.

Figure 5. Proteoglycan accumulation in cultures of passaged chondrocytes.

Passaged P2 or P3 cells derived from P0 bovine articular chondrocytes were treated 4 days without (panels A, B) or with 5 μM simvastatin (panels C, D, E and F) as labeled. Parallel cultures of cells shown in panels A, C and E were post-treated with 10 U/ml Streptomyces hyaluronidase for 3 hours (panels B, D and F) before fixation and staining overnight with DMMB. All images are depicted at similar magnification (20x objective, 50 μm bar) and taken under identical conditions; minor linear adjustments (Brightness / Contrast) were made to the image [42]. Insets represent digitally enlarged (~3.3x higher) images to better display cellular detail and include 50 μm bar for comparison. Images shown are representative fields of cells grown at 3 different densities per experiment and representative of 4–14 independent experiments.

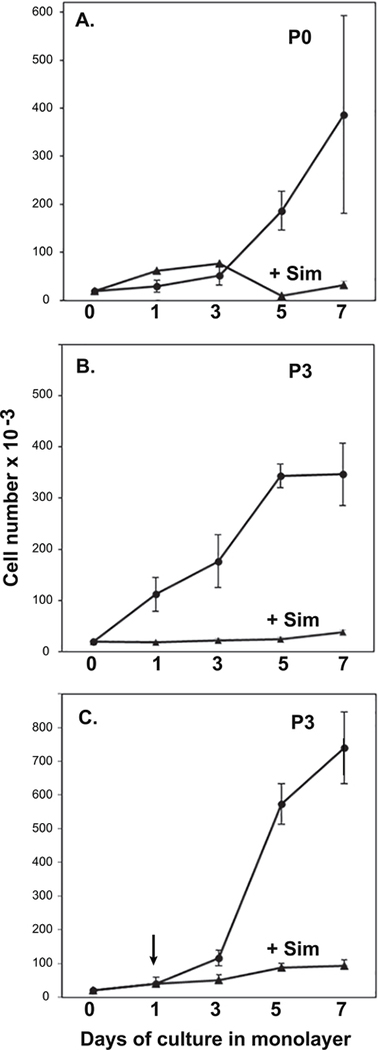

Effect of simvastatin on cell proliferation.

It was noted while examining the cells for the data shown in Fig. 5 that the fibroblast-like, untreated (de-differentiated) P2 and P3 cells were more rapidly proliferating as compared to cells treated with simvastatin. To expand on this observation, cell proliferation assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 6A, P0 untreated primary chondrocytes displayed little rapid change in cell density until 5 days in monolayer, after which the growth rate progressively increased. Treatment of the cells with simvastatin (starting from day 0), had little effect on the growth rate on days 1–3 but substantially reduced the enhanced proliferation of the P0 chondrocytes observed at days 5 and 7. Untreated P3 cells (Fig. 6B), exhibited enhanced proliferation starting at day 1. Treatment of P3 cells with simvastatin blocked the proliferation of the chondrocytes at each time point measured. In a third approach, P3 cells were allowed to proliferate for 3 days untreated, at which time one set of cells was treated with simvastatin and another left untreated. The purpose of this experiment was to test whether simvastatin treatment blocked proliferation because of cell toxicity. If cell toxicity was occurring, a dramatic drop in cell number would be expected. However, as shown in Fig. 6C, the addition of simvastatin gradually blocked the prolific growth of the P3 cells but did not diminish ongoing growth by these cells. Using a fluorescence Live/Dead assay as another approach, approximately 95% of the total P2 cells were viable (green fluorescent) after 4 days of culture in the absence or presence of simvastatin; ~5% took up the red dye. Primary P0 chondrocytes in monolayer were more viable than passaged P2 or P3 cells but included 1–2% red fluorescent cells after 4 days of simvastatin treatment. Thus, in addition to changes in morphology and renewed aggrecan production (Figs. 4 and 5), simvastatin also blocked the rapid proliferation of passaged cells derived from primary bovine articular chondrocytes with no apparent change in cell viability.

Figure 6. Effect of simvastatin on chondrocyte proliferation.

Primary (P0) bovine articular chondrocytes or P3 cells were plated at 20,000 cells/well into 12 well plates. Total cell numbers were determined on day 1 and every 2 days over the course of 7 days from duplicate wells for each condition. In panels A and B (P0 chondrocytes and P3 cells, respectively), 5 μM simvastatin (closed triangles) or vehicle (closed circles) was added at the time of plating. In panel C, 5 μM simvastatin (closed triangles) or vehicle (closed circles) was added during a media change on day 1. Data represent the average ± S.D. of 3 separate experiments.

Reversal of simvastatin effects on chondrocytes by the co-addition of cholesterol intermediates.

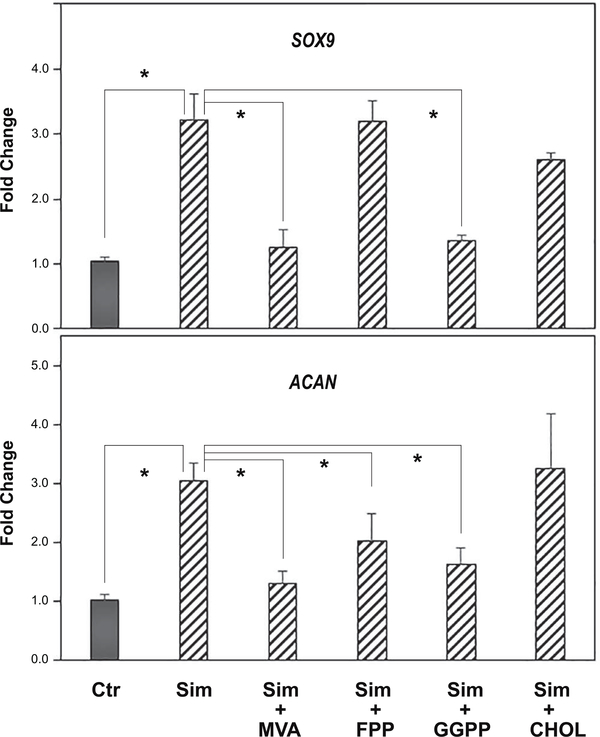

To address the mechanism of action of simvastatin on SOX9 and aggrecan, soluble intermediates in the cholesterol pathway were added together with simvastatin to passaged chondrocytes. As shown in Fig. 7, simvastatin alone enhanced the expression of SOX9 and ACAN mRNA in bovine P2 chondrocytes (hatched bars). The addition of mevalonic acid (MVA), the immediate precursor downstream of the statin block of HMG-CoA reductase, was able to reverse the simvastatin effect, resulting in the reduction of both SOX9 and ACAN mRNA expression. Thus, the bioactivity of simvastatin is due to its effect as an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase. However, the addition of soluble cholesterol (CHOL) did not block the enhancement of these two chondrocyte transcripts by simvastatin. This suggests that a requirement for cholesterol, such as in the generation of lipid rafts, was not necessary for the effects of simvastatin on chondrocyte re-differentiation. Addition of the intermediate, farnesylpyrophophate (FPP) also did not block or rescue the effects of simvastatin on SOX9 mRNA but displayed a partial effect on ACAN mRNA. Another intermediate, geranylgeranylpyrophosphate (GGPP), like MVA, blocked the stimulation of both SOX9 and ACAN mRNA by simvastatin. FPP and especially GGPP, are cholesterol intermediates used by cells for protein prenylation. These data were confirmed by examining SOX9 protein production in P3 cells under the same treatment conditions (Fig. 8). As shown, both MVA and GGPP were efficient at over-coming the simvastatin effect, with SOX9 protein production reduced to the same level or below that of control, untreated cells. The addition of cholesterol or FPP were less effective at blocking simvastatin. Values from densitometric analysis of the SOX9 bands are included with controls set = 1.00. Parreno et al. recently demonstrated that enhanced mRNA and protein expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was associated with the fibroblast-like phenotype of passaged chondrocytes [6]. As shown in the middle lanes of Fig. 8, αSMA was clearly present in lysates from control, untreated P3 cells. The αSMA band decreased in lysates from P3 cells treated with simvastatin as well as simvastatin plus FPP or CHOL. The addition of simvastatin plus MVA or GGPP blocked the simvastatin downregulation of αSMA. Essentially, the αSMA accumulation was the mirror image of the SOX9 results.

Figure 7. The capacity of cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates to reverse the effects of simvastatin on SOX9 and ACAN mRNA expression in passaged bovine chondrocytes.

SOX9 (top panel) and ACAN (bottom panel) mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis. SOX9 and ACAN expression in untreated control P3 cells (Ctr; dark bars) or P3 cells treated for 4 days with 5 μM simvastatin (hatched bars, labeled sim) in the absence or presence of 500 μM mevalonic acid (MVA), 10 μM farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), 10 μM geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) or 500 μM cholesterol (CHOL) are shown. Panels show the relative mRNA expression data, average ± SD (control P3 cells set to 1.0), of 3 independent experiments (performed at different times) each assayed in duplicate. * P <0.05.

The effect of simvastatin on human OA chondrocytes.

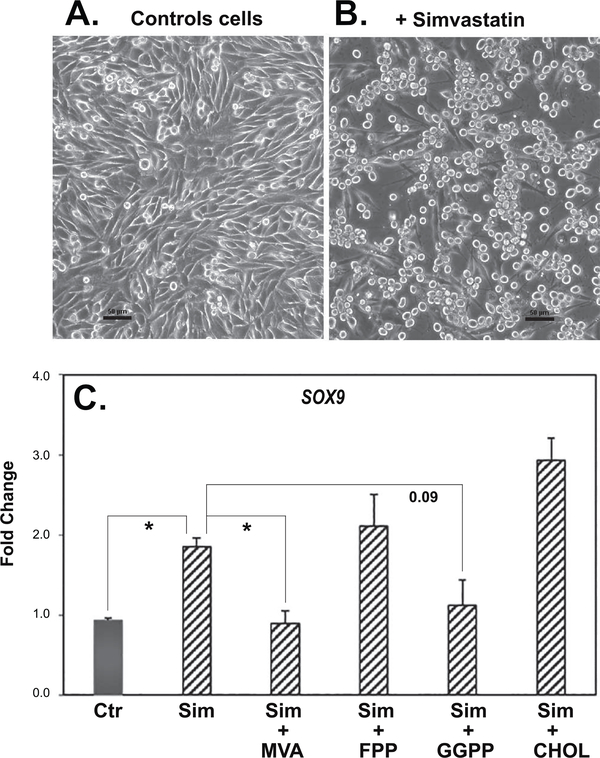

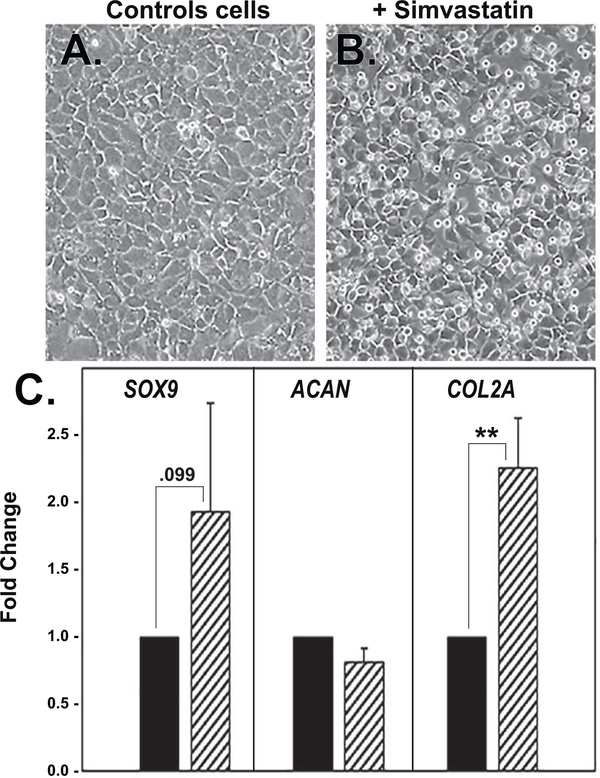

It has been suggested that human chondrocytes, derived from OA patients after knee arthroplasty, exhibit an altered phenotype that has similarities to de-differentiated chondrocytes [1, 3, 25]. Fig. 4E, 4F, depict examples of human OA chondrocytes (primary cells) grown in monolayer culture. The OA chondrocytes exhibit an elongated phenotype but not as fibroblast-like as P2 or P3 cells derived from primary bovine articular chondrocytes. Interestingly, treatment of human OA chondrocyte monolayers with simvastatin resulted in enhanced expression of SOX9 and COL2a but no changes in ACAN mRNA (Fig. 9). The data shown represent averaged values from 3 different patient cell preparations. Given that a stimulation of SOX9 and COL2A did occur suggests that P0 OA chondrocytes are at least responsive to agents that promote re-differentiation of passaged chondrocytes—certainly more so than what was observed with primary P0 cultures bovine chondrocytes (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). We cannot rule out that these differences in responsiveness could be age related as human samples were obtained from patient cartilages ranging between 47 and 75 years of age whereas the bovine chondrocytes were derived from cartilage of mature but young cattle. In another experiment, lysates from parallel cultures from each of these three OA chondrocyte preparations (ages 57–75 years old) were analyzed by western blotting for detection of SOX9 protein. As shown in Fig. 10, SOX9 protein was enhanced in each of these cultures following treatment with simvastatin. Densitometric analysis determined an average 4.1 ± 2.9-fold increase in SOX9 protein levels in these OA chondrocyte primary cultures stimulated by simvastatin. In addition, the co-treatment of cells with MVA, but not cholesterol, blocked the simvastatin effects on SOX9 protein. However, in the human chondrocytes, although effectiveness of FPP was observed, GGPP was again consistently more effective at reversing the simvastatin effects than FPP. This suggest that human OA chondrocytes are more dependent on GGPP as a substrate for protein prenylation.

Figure 9. Effect of simvastatin on marker genes indicative of changes in the phenotype of primary human OA chondrocytes.

Primary (P0) high density monolayer cultures of human OA chondrocytes exhibit a polygonal and flattened morphology (panel A) that becomes more rounded and cobblestone-like following treatment with simvastatin (panel B). Panel C depicts qRT-PCR analysis used to determine SOX9, ACAN and COL2A mRNA expression in primary human OA chondrocytes (vehicle control; dark bars) and changes in expression in cultures of the same OA chondrocytes following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin (hatched bars). Panels show the relative mRNA expression data, average ± SD (control P0 OA chondrocytes set to 1.0), of 3 independent experiments (performed at different times, using chondrocytes isolated from cartilage from three patients) each assayed in duplicate. ** P <0.01 and otherwise noted.

Figure 10. The capacity of cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates to reverse the effects of simvastatin on SOX9 protein accumulation in primary human OA chondrocytes.

Western blot analysis was used to determine changes in SOX9 protein in primary human OA articular chondrocytes without (left lanes labeled Control, Ctr; set to 1.00) or following 4 days of treatment with 5 μM simvastatin (right lanes, Sim) in the absence or presence of 500 μM mevalonic acid (MVA), 10 μM farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), 10 μM geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) or 500 μM cholesterol (CHOL) as labeled. Following detection of the ~70 kD SOX9 protein (70 kD), the same blots were stripped and re-probed for GAPDH and then a second time for β-actin. Values determined by densitometry show the fold-change in SOX9 band intensity after these treatments compared to untreated controls, with values normalized to β-ACTIN in the same lysate. Data from 3 independent experiments derived using chondrocytes isolated from 3 different patient cartilage samples (Exp #1, Exp #2, Exp #3) and performed at different times, are shown.

The effect of simvastatin on rat chondrosarcoma chondrocytes.

Rat chondrosarcoma (RCS) chondrocytes have long served as a useful chondrocyte permanent cell line. Our lab primarily uses an original long-term culture clone of the RCS tumor and we have designated this cell line as RCS-o [8–10]. They exhibit a variety of cell shapes from round-to-polygonal-to-spread even when cloned from a single cell as illustrated in Fig. 11A. This led us to hypothesize that RCS-o represents a chondrosarcoma chondrocyte we liken to a P1 or P2 passaged bovine chondrocyte. To explore this possibility we treated RCS-o cultures with or without simvastatin. As with passaged bovine or human P0 OA chondrocytes, simvastatin treatment resulted in a change in cell shape (round to polygonal, Fig. 11B) and a 2-fold increase in Sox9 mRNA expression (Fig. 11C). Moreover, the simvastatin effect was blocked by co-treatment with MVA and GGPP but not with FPP or CHOL. Many chondrocyte cell lines do not display a typical round/polygonal morphology. These results suggest that the effects of simvastatin to promote a chondrocyte phenotype can be extended to chondrocyte cell lines such as RCS-o.

Figure 11. The capacity of cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates to reverse the effects of simvastatin on Sox9 mRNA expression in rat chondrosarcoma chondrocytes.

High density monolayer cultures of RCS-o chondrocytes exhibit an extended fusiform morphology (panel A) that becomes more rounded following treatment with simvastatin (panel B). Bars: 50 μm. Panel C depicts Sox9 mRNA expression determined by qRT-PCR analysis in vehicle control RCS chondrocytes (Ctr; dark bar) or RCS chondrocytes treated for 2 days with 5 μM simvastatin (hatched bars) in the absence or presence of 500 μM mevalonic acid (MVA), 10 μM farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), 10 μM geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) or 500 μM cholesterol (CHOL) as labeled. Panels show the relative mRNA expression data, average ± SD (control RCS cells set to 1.0), of 2 independent experiments (performed at different times) each assayed in duplicate. * P <0.05 or otherwise noted.

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate that simvastatin can reverse changes in the articular chondrocyte phenotype that occur due to passage—changes often designated as de-differentiation. The most apparent effects of simvastatin included a change in cell shape; from a fusiform, fibroblast-like morphology to a rounded or cobblestone cell shape that mimics primary chondrocytes in vitro. Another readily apparent change was a striking diminution of cell proliferation (Fig. 6); again mimicking the initial days of in vitro culture of primary chondrocytes. At 5 and 7 days even primary chondrocytes begin to exhibit enhanced proliferation likely due to a loss in phenotype and, represents another event blocked by simvastatin treatment. This reversal by simvastatin also included increases in expression of SOX9, ACAN and COL2A, BMP2 and HAS2 mRNA as well as a decrease in COL1 in passaged bovine articular chondrocytes. These increases were matched by increased accumulation of SOX9 protein and renewed deposition of extracellular proteoglycan observed as patches of stained pericellular regions radiating outward.

The hypothesis that we set out to test was whether the capacity of simvastatin to block CD44 degradation via blocking maintenance of cholesterol-dependent lipid rafts, resulting in reduced ADAM10-mediated sheddase activity toward CD44 [7], was also necessary for optimal re-differentiation. That proved not to be the case in this study. The co-treatment of simvastatin plus cholesterol failed to reverse the effects of simvastatin on SOX9 or ACAN in bovine, human OA or RCS-o chondrocytes. However, the inclusion of other cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates namely, MEV, GGPP and sometimes partial reversal with FPP, blocked the effects of simvastatin on the expression of these marker genes/gene products as well as αSMA. Given the distinctive effects of cholesterol biosynthesis intermediates on the simvastatin effect on phenotype, reduction in protein prenylation is the likely mechanism responsible for re-differentiation of passaged chondrocytes observed in this study. Several investigators have documented the side-effects of statins (simvastatin in particular) to block FPP and GGPP-mediated prenylation of intracellular proteins, especially small GTP binding proteins such as RhoA [7, 26–28] (reviewed in [29]). GTPases such as RhoA are required for maintenance and organization of the actin cytoskeleton, especially the stress fibers observed by many fibroblast-like cells in monolayer culture [30]. Such stress fibers are often associated with the flattened, fibroblast morphology of de-differentiated chondrocytes. The use of 3D culturing methodologies (namely alginate beads [2, 11, 21, 31–34] or agarose gel layers [32]) to induce re-differentiation are thought to act by promoting the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton resulting in the rounding of the cells. Similarly, destabilization and depolymerization of the actin cytoskeleton via treatment with latrunculin or cytochalasin also promotes chondrocyte rounding and enhanced biosynthesis of aggrecan [35–37]. Thus, it is possible that the changes in cell shape and proteoglycan deposition observed in P2 and P3 bovine cells treated with simvastatin (Fig. 5C, 5D) reflect cytoskeletal destabilization due to inhibition of GTP binding proteins such as RhoA.

In addition to helping to decipher the intracellular mechanisms involved in re-differentiation, there is practical / clinical significance to determining new ways to promote and maintain the chondrocyte phenotype. First and foremost is to provide methods to re-differentiated expanded cultures of articular chondrocytes. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is used to repair small cartilage defects, particularly in younger-age patients. The procedure has been refined to include various matrix supports but still relies on the expansion of autologous chondrocytes in culture [38], a procedure that results in the de-differentiation of the chondrocytes. Following transplant, it is assumed that the cells re-differentiate into functional chondrocytes due to the local environment. Although ACI is in clinical use [39], improvements are still needed to extend its application to larger defects to treat OA and many approaches have been explored [5, 6]. The use of simvastatin may provide a safe, reliable means to begin the re-differentiation.

Secondly, investigators have suggested that human OA chondrocytes exhibit an altered gene expression—a change in expression that resembles de-differentiated chondrocytes [3, 25]. In this study we did not have age-matched normal human articular chondrocytes to compare with our OA tissue-derived chondrocytes for changes (i.e., downregulation) in SOX9, ACAN or COL2A expression. Nonetheless, the baseline level of SOX9 mRNA and protein, in P0 human OA chondrocyte preparations from cartilage from three different patients (Figs. 9, 10), was enhanced by treatment with 5 μM simvastatin. COL2A mRNA was also enhanced by simvastatin but interestingly no increase in ACAN mRNA was observed. This differed from normal bovine articular chondrocytes in which little to no change in SOX9 mRNA or protein was observed in primary P0 chondrocytes treated with simvastatin (Figs 1, 2, 3). The absence of normal human P0 chondrocytes for comparison is a limitation of this study. Our data could suggest that human OA chondrocytes exist in a partially de-differentiated in vivo before isolation or, that these cells more readily de-differentiate when placed into monolayer culture than primary bovine chondrocytes. Discerning which was beyond the scope of this study. However, one could thus speculate on the possibility local application of statins to cartilage defects might provide a means to promote or maintain a mature articular chondrocyte phenotype in vivo. The use of statins are under consideration for the treatment of bone catabolic diseases, especially using local rather than systemic application (reviewed in [29]). Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that statin inhibition of geranylgeranyl prenylation can block enhanced MMP expression and production in IL-1/oncostatin-induced bovine nasal cartilage or human OA cartilage and chondrocytes [40]. In another, differential expression study, human osteophyte cartilage was shown to express COL1, COLX, MMP9, MMP13 and HAS1 (among other genes) whereas increased SOX9 and GREM1 expression was associated with human articular cartilages [41]. Their goal was to determine transcriptional differences between mesenchymal stem/progenitor cell-derived transient repair tissue and more phenotypically-stable hyaline cartilage. Although beyond our supportive data, it is intriguing to speculate that simvastatin may reduce or block de-differentiation by chondrocytes in OA. Also, including simvastatin in some portion of the cell culture expansion phase prior to ACI might improve the success of this technique [38, 39]. Our future goal is to determine whether chondrocytes can tolerate simvastatin (as a pathway inhibitor) and serve for long term use as positive regulator of the chondrocyte phenotype.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Joani Zary Oswald for her technical assistance with this project. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health; AR066581 (WK) and AR039507 (CBK) and funds from East Carolina University.

Abbreviations:

- HA

hyaluronan

- OA

osteoarthritis

- CHOL

soluble cholesterol

- DMMB

dimethylmethylene blue

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- FPP

farnesylpyrophosphate

- GGPP

geranylgeranylpyrophosphate

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- Mev

mevalonic acid

- RCS

rat chondrosarcoma

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

Footnotes

Declarations of interest by the authors: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Ono Y, Sakai T, Hiraiwa H, Hamada T, Omachi T, Nakashima M, et al. , Chondrogenic capacity and alterations in hyaluronan synthesis of cultured human osteoarthritic chondrocytes, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 435 (2013) 733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Takahashi N, Knudson CB, Thankamony S, Ariyoshi W, Mellor L, Im HJ, et al. , Induction of CD44 cleavage in articular chondrocytes, Arthritis Rheum 62 (2010) 1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stokes DG, Liu G, Coimbra IB, Piera-Velazquez S, Crowl RM, Jimenez SA, Assessment of the gene expression profile of differentiated and dedifferentiated human fetal chondrocytes by microarray analysis, Arthritis Rheum 46 (2002) 404–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cha BH, Kim JH, Kang SW, Do HJ, Jang JW, Choi YR, et al. , Cartilage tissue formation from dedifferentiated chondrocytes by codelivery of BMP-2 and SOX-9 genes encoding bicistronic vector, Cell Transplant. 22 (2013) 1519–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Parreno J, Bianchi VJ, Sermer C, Regmi SC, Backstein D, Schmidt TA, et al. , Adherent agarose mold cultures: An in vitro platform for multi-factorial assessment of passaged chondrocyte redifferentiation, J. Orthop. Res 36 (2018) 2392–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Parreno J, Raju S, Wu PH, Kandel RA, MRTF-A signaling regulates the acquisition of the contractile phenotype in dedifferentiated chondrocytes, Matrix Biol. 62 (2017) 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Terabe K, Takahashi N, Takemoto T, Knudson W, Ishiguro N, Kojima T, Simvastatin inhibits CD44 fragmentation in chondrocytes, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 604 (2016) 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Huang Y, Askew EB, Knudson CB, Knudson W, CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of HAS2 in rat chondrosarcoma chondrocytes demonstrates the requirement of hyaluronan for aggrecan retention, Matrix Biol. 56 (2016) 74–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mellor L, Knudson CB, Hida D, Askew EB, Knudson W, Intracellular domain fragment of CD44 alters CD44 function in chondrocytes, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 25838–25850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Danielson BT, Knudson CB, Knudson W, Extracellular processing of the cartilage proteoglycan aggregate and its effect on CD44-mediated internalization of hyaluronan, J. Biol. Chem 290 (2015) 9555–9570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Benya PD, Shaffer JD, Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels, Cell 30 (1982) 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tew SR, Hardingham TE, Regulation of SOX9 mRNA in human articular chondrocytes involving p38 MAPK activation and mRNA stabilization, J. Biol. Chem 281 (2006) 39471–39479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hardingham TE, Oldershaw RA, Tew SR, Cartilage, SOX9 and Notch signals in chondrogenesis, J. Anat 209 (2006) 469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ishizuka S, Askew EB, Ishizuka N, Knudson CB, Knudson W, 4-Methylumbelliferone Diminishes Catabolically Activated Articular Chondrocytes and Cartilage Explants via a Mechanism Independent of Hyaluronan Inhibition, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 12087–12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Choi HU, Meyer K, Swarm R, Mucopolysaccharide and protein--polysaccharide of a transplantable rat chondrosarcoma, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 68 (1971) 877–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kucharska AM, Kuettner KE, Kimura JH, Biochemical characterization of long-term culture of the Swarm rat chondrosarcoma chondrocytes in agarose, J. Orthop. Res. 8 (1990) 781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ, Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 883 (1986) 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ, A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures, Connect. Tissue Res 9 (1982) 247–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shintani N, Kurth T, Hunziker EB, Expression of cartilage-related genes in bovine synovial tissue, J. Orthop. Res 25 (2007) 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Indrawattana N, Chen G, Tadokoro M, Shann LH, Ohgushi H, Tateishi T, et al. , Growth factor combination for chondrogenic induction from human mesenchymal stem cell, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 320 (2004) 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gan L, Kandel RA, In vitro cartilage tissue formation by Co-culture of primary and passaged chondrocytes, Tissue Eng. 13 (2007) 831–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Knudson W, Ishizuka S, Terabe K, Askew EB, Knudson CB, The pericellular hyaluronan of articular chondrocytes, Matrix Biol, in press, pii: S0945–053X(17)30437–7. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.02.005. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ariyoshi W, Knudson CB, Luo N, Fosang AJ, Knudson W, Internalization of aggrecan G1 domain neoepitope ITEGE in chondrocytes requires CD44, J. Biol. Chem 285 (2010) 36216–36224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Knudson W, Aguiar DJ, Hua Q, Knudson CB, CD44-anchored hyaluronan-rich pericellular matrices: An ultrastructural and biochemical analysis, Exp. Cell Res 228 (1996) 216–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Goldring MB, Goldring SR, Osteoarthritis J Cell Physiol. 213 (2007) 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rattan S, 3-Hydroxymethyl coenzyme A reductase inhibition attenuates spontaneous smooth muscle tone via RhoA/ROCK pathway regulated by RhoA prenylation, Am. J. Physiol 298 (2010) G962–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Allal C, Favre G, Couderc B, Salicio S, Sixou S, Hamilton AD, et al. , RhoA prenylation is required for promotion of cell growth and transformation and cytoskeleton organization but not for induction of serum response element transcription, J. Biol. Chem 275 (2000) 31001–31008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ariyoshi W, Okinaga T, Knudson CB, Knudson W, Nishihara T, High molecular weight hyaluronic acid regulates osteoclast formation by inhibiting receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand through Rho kinase, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22 (2014) 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang Y, Bradley AD, Wang D, Reinhardt RA, Statins, bone metabolism and treatment of bone catabolic diseases, Pharmacol. Res 88 (2014) 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sit ST, Manser E, Rho GTPases and their role in organizing the actin cytoskeleton, J. Cell Sci 124 (2011) 679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].D’Souza AL, Masuda K, Otten L, Nishida Y, Knudson W, Thonar E-JMA, Differential effects of interleukin-1 on hyaluronan and proteoglycan metabolism in two compartments of the matrix formed by articular chondrocytes maintained in alginate, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 374 (2000) 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hauselmann HJ, Aydelotte MB, Thonar EJM, Gitelis SH, Kuettner KE, Alginate beads: A new culture system for articular chondrocytes, in: Kuettner KE, Schleyerbach R, Peyron JG, Hascall VC (Eds.), Articular Cartilage and Osteoarthritis, Raven Press, New York, 1992, pp. 701–702. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schulze-Tanzil G, Mobasheri A, de Souza P, John T, Shakibaei M, Loss of chondrogenic potential in dedifferentiated chondrocytes correlates with deficient Shc-Erk interaction and apoptosis, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 12 (2004) 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bonaventure J, Kadhom N, Cohen-Solal L, Ng KH, Bourguignon J, Lasselin C, et al. , Reexpression of cartilage-specific genes by dedifferentiated human articular chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads, Exp. Cell Res 212 (1994) 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Newman P, Watt FM, Influence of cytochalasin D-induced changes in cell shape on proteoglycan synthesis by cultured articular chondrocytes, Exp. Cell Res 178 (1988) 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brown PD, Benya PD, Alterations in chondrocyte cytoskeletal architecture during phenotypic modulation by retinoic acid and dihydrocytochalasin B-induced reexpression, J. Cell Biol 106 (1988) 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nofal GA, Knudson CB, Latrunculin and cytochalasin decrease chondrocyte matrix retention, J. Histochem. Cytochem 50 (2002) 1313–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Minas T, Ogura T, Bryant T, Autologous chondrocyte implantation, J. Bone Joint Surg. Essential Surg. Tech 6 (2016) e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Peterson L, Brittberg M, Kiviranta I, Akerlund EL, Lindahl A, Autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Biomechanics and long-term durability, Am. J. Sports Med 30 (2002) 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Barter MJ, Hui W, Lakey RL, Catterall JB, Cawston TE, Young DA, Lipophilic statins prevent matrix metalloproteinase-mediated cartilage collagen breakdown by inhibiting protein geranylgeranylation, Ann. Rheum. Dis 69 (2010) 2189–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gelse K, Ekici AB, Cipa F, Swoboda B, Carl HD, Olk A, et al. , Molecular differentiation between osteophytic and articular cartilage--clues for a transient and permanent chondrocyte phenotype, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20 (2012) 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rossner M, Yamada KM, What’s in a picture? The temptation of image manipulation, J. Cell Biol 166 (2004) 11–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]