Highlights

-

•

Exergaming has shown a positive effect in promoting preschool children's moderate-to-vigorous physical activity at school.

-

•

Exergaming has the potential to enhance preschool children's perceived competence and motor skill competence.

-

•

The preschool years are critical for children's development of motor skill competence; preschool children's motor skill competence increased even after 8 weeks.

-

•

Preschool boys demonstrated higher levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than girls did at school.

Keywords: Active video games, Childhood obesity, Gender differences, Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, Recess

Abstract

Background

Few school settings offer opportunities for preschool children to engage in structured physical activity, and only a few studies have been conducted examining exergaming's effectiveness on health outcomes in this age group. This study's purpose, therefore, was to examine a school-based exergaming intervention's effect on preschool children's perceived competence (PC), motor skill competence (MSC), and physical activity versus usual care (recess), as well as to examine gender differences for these outcomes.

Methods

A total of 65 preschool children from 2 underserved urban schools were assigned to 1 of 2 conditions, with the school as the experimental unit: (1) usual care recess group (8 weeks of 100min of recess/week (5 days × 20 min)) and (2) exergaming intervention group (8 weeks of 100min of exergaming/week (5 days × 20 min) at school). All children underwent identical assessments of PC, MSC, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) at baseline and at the end of the 8th week.

Results

A significant Group × Time effect was observed for MVPA, F(1, 52) = 4.37, p = 0.04, = 0.04, but not for PC, F(1, 52) = 0.83, p = 0.37, = 0.02, or MSC, F(1, 52) = 0.02, p = 0.88, = 0.00. Specifically, the intervention children displayed significantly greater increased MVPA after 8weeks than the comparison children. Additionally, there was a significant time effect for MSC, F(1, 52) = 15.61, p < 0.01, = 0.23, and gender effect for MVPA, F(1, 52) = 5.06, p = 0.02, = 0.09. Although all preschoolers’ MSC improved across time, boys demonstrated greater MVPA than girls at both time points.

Conclusion

Exergaming showed a positive effect in promoting preschool children's MVPA at school and has the potential to enhance PC and MSC. More research with larger sample sizes and longer study durations are warranted.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has grown from 6.5% to 16.9% in the United States in the past 3 decades, which is partially owing to low physical activity (PA).1 Low PA also results in low cardiovascular fitness, which, along with obesity, increases hypertension and hypercholesterolemia risk during childhood and contributes to chronic disease development, such as hypertension and diabetes, in adulthood.2, 3, 4 PA participation plays a key role in preventing and decreasing obesity and low cardiovascular fitness among young children, and children of low socioeconomic status are particularly more likely to be sedentary.5, 6 Furthermore, the preschool years (ages 4–5 years) have been identified as a crucial time to promote healthy lifestyle habits, which could assist in the prevention of obesity and chronic diseases as children age.7, 8 However, few studies have focused on the effects of PA interventions in this population in general and underserved populations in particular.

1.1. Literature on intervention studies among preschool children

Available intervention studies of curricular changes that promote preschool children's PA have yielded inconclusive observations, with some indicating significantly increased PA between intervention and control groups,9, 10, 11 whereas others found no between-group differences.12, 13, 14 In contrast with traditional PA interventions, technology-enabled interventions such as exergames have emerged, demonstrating initial positive influences on some components of motor skill competence (MSC).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Research has also suggested that low PA levels in preschool children might be related to delayed acquisition of MSC in early childhood.22 Although school-based settings offer opportunities to promote preschool children's health, most empirical studies to date were conducted in daycare and Head Start centers.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Thus, the implementation of developmentally appropriate and engaging PA interventions for preschool children within school-based settings has become a high research priority.

1.2. Exergaming for PA promotion

Exergaming refers to active video games that are also a form of exercise.23 Despite exergaming's screen-based nature, exergaming has the potential to help promote preschool children's PA. Recently, exergaming has been increasingly used within school-based settings as an innovative and fun approach for promoting a physically active lifestyle, with positive and promising results.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 However, previous studies targeted only older children and adolescents (age range: 7–18 years). Yet, many developmentally appropriate exergames (e.g., Wii Nickelodeon Fit) have been developed for preschool children, thus facilitating examination of exergaming's effect among this population. Moreover, most exergaming studies have focused on only 1 outcome (e.g., energy expenditure).24, 29 Therefore, such studies have yet to explain exergaming's effects on other important aspects of child development such as MSC and perceived competence (PC).

1.3. Competence motivation theory

According to the competence motivation theory,30 a child's behavior can be explained and predicted by PC and mastery competence. PC refers to children's self-evaluative judgment about their ability to accomplish certain tasks, whereas mastery competence refers to the actual ability to complete the tasks (e.g., actual MSC).31 According to this theory, successfully mastering skills/tasks (e.g., improvement of MSC resulting from exergaming play)will augment PC, which in turn boostsmotivated behaviors (e.g., PA participation) and actual performance (e.g., MSC).32, 33 Furthermore, better MSC is consistently associated with higher PA in longitudinal and cross-sectional studies.34, 35, 36

Recent studies suggest that exergaming has the potential to improve older children's PC, MSC, and PA. For example, exergaming has been shown to be effective in promoting elementary school children's PA levels,24,37, 38, 39, 40 and PC or self-efficacy.41, 42, 43 Yet, exergaming's effectiveness on children's MSC is still under heated debate. Zeng and Gao44 in their review suggested that exergaming could serve as an alternative tool for enhancing body management skills (e.g., balance, postural stability), but that exergaming offered insufficient stimulus for locomotor and object control skills changes among children and young adults. However, little empirical evidence of exergaming's effect on MSC in preschool children is available and suggests an important avenue for research.

1.4. Gender differences

Gender differences have been reported for children's MSC, PC, and PA.45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 Specifically, boys have been found to be more proficient in motor competence for most, but not all, motor skills (e.g., throwing)45, 46 and are more likely to exhibit greater PC in sport or PA than girls.47, 48 Boys were also more physically active than girls in most empirical studies.6, 49, 50 Yet, such gender differences in preschool children remain largely unexplored.51 Thus, there is a clear need to examine the gender differences for these variables in this population.

This study's purpose was 2-fold: (1) to examine exergaming's effects on PC, MSC, and PA in underserved preschool children and (2) to evaluate whether gender differences exist for exergaming's effect on PC, MSC, and PA. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating exergaming's effects on these outcomes in this population. Examining a novel exergaming intervention's effects on children's PC, MSC, and PA will help researchers and health professionals to understand how innovative school-based PA interventions may be implemented for preschool children's PA and health promotion. This study is also significant because it investigates the potential gender differences that an exergaming intervention may minimize among this age group, thus providing further understanding ofhow a school-based exergaming program among preschool children might be implemented with these differences in mind.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design and participants

The sample size was calculated by G*Power 3.1 (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/en.html), indicating that 60 participants would be sufficient for 80% power (α = 0.05, effect size = 0.30) to test the primary outcome (i.e., PA). This study used a 2-arm experimental design with repeated measures. A total of 65 preschoolers (33 girls; 4.45 ± 0.46 years, mean ± SD) from 2 urban underserved elementary schools in a Midwestern U.S. state were enrolled, and were then assigned to either the exergaming intervention or a standard care comparison group, with the school as the experimental unit. The school district within which the study was conducted offered half-day early childhood programs free of charge to parents. Two classes (morning and afternoon) with approximately 10–20 children in each class from each school were involved in the current study. Participants were in school for approximately 3h from Monday to Friday. The intervention took place over an 8-week period for 30min per session (including 20 min of exergaming and 10 min of warm-up and cool-down) 5days per week. Children's baseline PC, MSC, and PA were measured before and after the intervention.

To be eligible for this study, a school had to offer a preschool program (e.g., High Five) for children 4–5years of age and serve low-income communities. The inclusion criteria for children were that they (1) were enrolled in a public Title I elementary school (i.e., >50% of the children receive free or reduced-price meals), (2) were 4–5years of age, (3) had no diagnosed physical or mental disability, and (4) had parental consent and the preschooler's verbal assent. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board and school district according to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

2.2. Procedures

Participants were recruited at the schools’ preschool classes with assistance from the classroom teachers. Specifically, the teachers put flyers describing the study into potential participants’ backpacks and instructed them to give the flyers to their parents. The preschool children who returned the signed consent forms were then screened by the researchers. At baseline, the researchers administered a battery of assessments for the outcomes. All children underwent identical assessments at theend of the 8th week. To protect privacy, PCassessments occurred in private rooms during one-on-one sessions. MSC testing took place in the schools’ gyms, and PA tracking took place throughout the entirety of the school day. All data were collected over a 2-week period at baseline. First, the research team introduced the study and obtained consent. Then, children's height, weight, PC, MSC, and PA were measured based on school schedules and space availabilities both at baseline and after the 8-week intervention period for each testing cycle. If a child was absent from school on a day when measurements were being conducted, we collected these data on another day. These procedures ensured that missing data were minimized. A gift card for USD20 was given to each child's parents as an incentive for successfully completing all data collection sessions.

2.3. Intervention implementation

2.3.1. Exergaming condition

The primary researcher collaborated with school administrators and teachers, and incorporated exergaming into the intervention school's preschool curriculum. Specifically, the research team set up 8 exergaming stations in a large room separate from the main classroom. Each station was equipped with 1 exergaming system (Wii or Xbox Kinect), a television, and necessary ancillary supplies. Several developmentally appropriate exergames, such as Wii (Nintendo, Kyoto, Japan) Just Dance for Kids (Ubisoft, San Francisco, CA, USA), Wii Nickelodeon Fit (Nickelodeon, New York, NY, USA), and Xbox 360 Kinect (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) Just Dance for Kids (Ubisoft), were offered during the program, which promoted autonomy and sustained motivation for participation across time. Depending on the children's desires, exergaming play occurred individually, in pairs, or as a group, with the supervising teacher or research assistant assisting children in gameplay throughout to ensure continuous gameplay and, thus, PA. Exergaming sessions included daily 20-min nonstop exergaming play, with about 10min daily allocated for organization (e.g., lining up and walking down the hallway to exergaming room) and warm-up/cool-down time.

2.3.2. Comparison condition

Standard care was represented by recess and implemented at the comparison school. Recess time remained constant throughout the school year, with the comparison school offering identical active time to that of the intervention school. Recess was held on an outside playground with standard playground equipment apparatus and a grass field. On some occasions, recess had to be held within a school classroom owing to poor weather. Recess was supervised by the classroom teachers and teaching aids, but no structured PA was offered during the period. Participants engaged in varied activities during recess, such as chasing, tag, 4 square, and playing with other playground equipment (e.g., slides, swings).

2.3.3. Intervention fidelity

Intervention fidelity was continuously monitored for all intervention components. Specifically, the primary researcher met weekly with the exercise interventionist (NZ) for program training and monitoring to ensure consistency of the exergaming program at the school site. The research team monitored the PA intervention implementation on a weekly basis with previously established protocols. Research process evaluators were provided with a standardized protocol for each school visit and completed a checklist for each visit indicating the elements of the protocol that were covered in each PA session. We also collected process and implementation surveys on a regular basis to monitor implementation and content fidelity and child engagement. In this study, intervention fidelity exceeded 90% for the protocol elements covered in a given PA session.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Demographic and anthropometric data

Children's demographic information (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity) were collected from the teachers’ rosters. Their height and weight were assessed with a Seca stadiometer (Seca GmbH & Co. KG., Hamburg, Germany) and Detecto digital weight scale (Detecto, Web City, MO, USA), respectively, at each time point, with each child measured in a private room adjacent to their classroom.

2.4.2. PA Levels

PA was assessed by ActiGraph GT9X Link accelerometers (ActiGraph Corp., Pensacola, FL, USA). The ActiGraph Link is lightweight and resembles a watch. It is a valid and reliable measure of PA among children in school settings and free-livingsettings.52, 53 Specifically, children were instructed to wear the accelerometers on the nondominant wrist at all times during the school day for 3 school days during the first week baseline and after the 8th week of the study. Activity counts were set at 1-s epoch given the sporadic nature of children's PA. The activity counts recorded were interpreted using empirically based cut points that defined different intensities (sedentary: 0–820; light PA: 821–2830; moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA): ≥2831 for ActiGraph vector magnitude) of preschool children's PA.52 Compliance with wearing accelerometers was facilitated according to Trost et al.53 Children's average percentages of time in MVPA at school were used as the outcome. Notably, the accelerometers were not allowed to be taken home given the following considerations: (1) additional burden for underserved families, (2) possibility of lost or stolen devices, and (3) incomplete and inaccurate measurements. Therefore, only PA during school time was used for the current study.

2.4.3. MSC

The Test of Gross Motor Development-2nd edition (TGMD-2)54 was used to assess each participant's MSC. The TGMD-2 is a qualitative measure of the gross motor skills of children aged 3–10years. The 5 skills tested were subdivided into 2 skill areas: locomotor skills (run, hop, and jump) and object control skills (throw and kick). Children executed each skill twice, and the tests were videotaped for later evaluation. To indicate skill performance, qualitative performance criteria were scored, with 1 indicating its presence and 0 indicating its absence. If a skill was assessed using 3 performance criteria, the raw scores could thus vary between 0 and 6. The sum of the scores was used as each child's MSC. Notably, 2 trained researchers (NZ, ZCP) assessed and scored the TGMD-2 assessments, with greater than 90% agreement between these researchers.

2.4.4. PC

The subscale of perceived physical competence from the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance55 was used to examine PC. The scale was selected for the following reasons: (1) it has strong psychometric properties for children 4years of age and older (i.e., α > 0.70);55 (2) it is developmental in nature, reflecting children's changing perception of self at young ages; and (3) it is widely used and accepted in the literature.56, 57 Children responded to a 5-item perceived physical competence survey using a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 (not to good) to 4 (really to good)). The average score was calculated and used as a measure of each child's PC, with the assessment individually administered within a private room at each school to protect the children's privacy.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were imported from Excel into an SPSS Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) dataset for descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Screening for outliers and non-normality was conducted before the main analysis. First, a descriptive analysis was conducted to describe the sample characteristics, including frequencies of gender and race/ethnicity and all variables’ means and standard deviations. Second, a multivariate analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to examine changes in preschool children's PC, MSC, and MVPA across time. The between-subject factors were group (i.e., intervention vs. comparison school) and gender (boys vs. girls), whereas the within-subject factor was time. A significant Group × Time interaction effect would indicate that children in the intervention group have a different amount of the change in the outcomes compared with those of the comparison group, which was the major focus of this study. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical analyses, with effect sizes reported for each comparison. Specifically, partial eta-squared () was used as an index of effect size, for which small, medium, and large effect sizes were designated as 0.10, 0.25, and 0.40, respectively.58

3. Results

A total of 9 preschool children had missing data or outliers for 1 or more outcome variables at either baseline or 8 weeks, and thus were removed from the analysis. The final sample comprised 56 preschool children (mean age: 4.46 years; 31 girls). Detailed demographic and anthropometric information is displayed in Table1. Table2 shows the descriptive results for the preschool children's PC, MSC, and MVPA between intervention/gender groups and across time. On average, the preschool children demonstrated moderate levels of PC and MSC since the means of these variables were above the median scores across time (PC = 2.5; MSC = 24). Notably, children spent nearly 40% of school time in MVPA.

Table1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| School A (n = 20) | School B (n = 36) | Total (n = 56) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Girl | 9 (45) | 22 (61.11) | 31 (55.36) |

| Boy | 11 (55) | 14 (38.89) | 25 (44.64) |

| Race | |||

| White | 3 (15) | 20 (55.56) | 23 (41.07) |

| Black | 12 (60) | 5 (13.89) | 17 (30.36) |

| Hispanic | 4 (20) | 5 (13.89) | 9 (16.07) |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 5 (13.89) | 5 (8.93) |

| Other | 1 (5) | 1 (2.77) | 2 (3.57) |

| Age (year) | 4.72 ± 0.34 | 4.33 ± 0.46 | 4.46 ± 0.46 |

| Height (cm) | 111.58 ± 5.61 | 107.07 ± 5.77 | 108.71 ± 6.07 |

| Weight (kg) | 20.22 ± 3.99 | 18.27 ± 2.75 | 18.98 ± 3.35 |

Note: Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD.

Table2.

Descriptive statistics of children's MVPA, MSC, and PC (mean ± SD).

| Pre-test |

Post-test |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | Boy | All | Girl | Boy | All | |

| Exergaming (n = 20) | ||||||

| MVPA (min/day) | 37.86 ± 7.84 | 38.46 ± 4.84 | 38.19 ± 6.19 | 40.54 ± 6.80 | 43.62 ± 3.69 | 42.24 ± 5.39 |

| MSC | 31.89 ± 4.40 | 31.55 ± 4.89 | 31.7 ± 4.55 | 34.22 ± 2.05 | 35.55 ± 5.77 | 34.95 ± 4.44 |

| PC | 3.26 ± 0.39 | 3.08 ± 0.49 | 3.16 ± 0.44 | 3.15 ± 0.44 | 3.24 ± 0.60 | 3.20 ± 0.52 |

| Comparison (n = 36) | ||||||

| MVPA (min/day) | 36.46 ± 10.07 | 44.09 ± 13.66 | 39.43 ± 12.01 | 36.07 ± 5.63 | 39.53 ± 2.89 | 37.42 ± 5.00 |

| MSC | 29.09 ± 8.62 | 33.86 ± 4.85 | 30.94 ± 7.67 | 33.82 ± 7.47 | 35.00 ± 5.46 | 34.28 ± 6.70 |

| PC | 3.14 ± 0.59 | 3.35 ± 0.29 | 3.21 ± 0.50 | 2.96 ± 0.57 | 3.24 ± 0.58 | 3.07 ± 0.58 |

Abbreviations: MSC = motor skill competence; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PC = perceived competence.

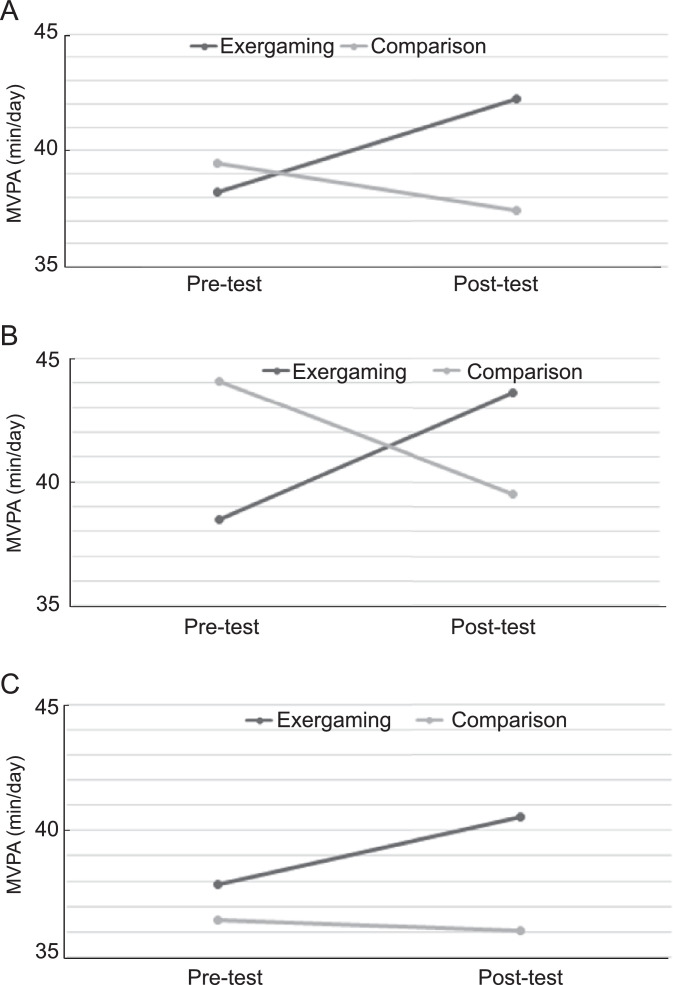

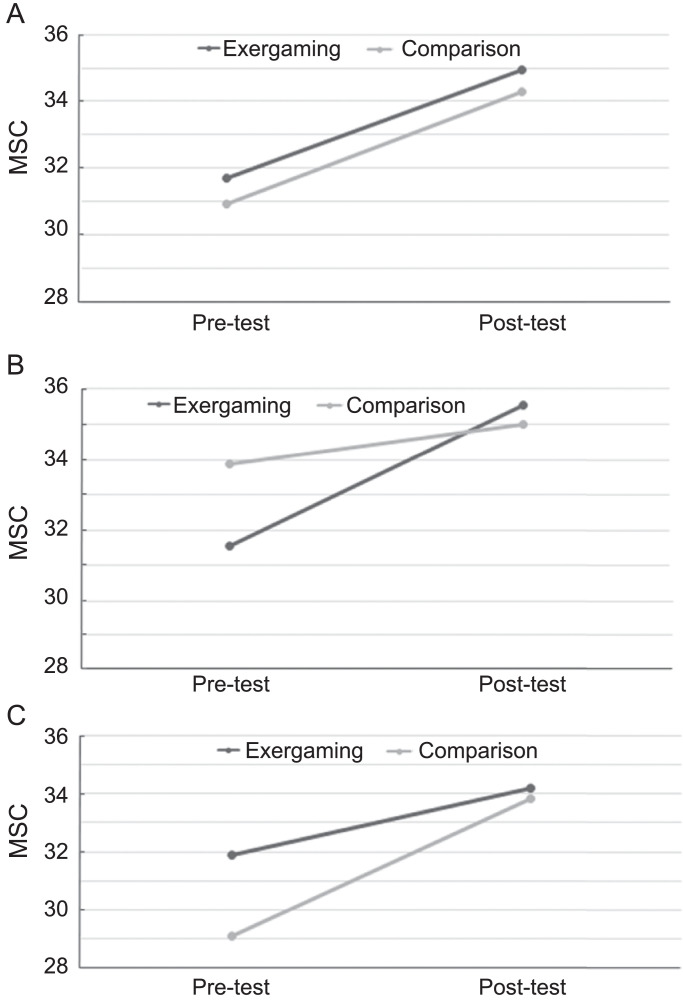

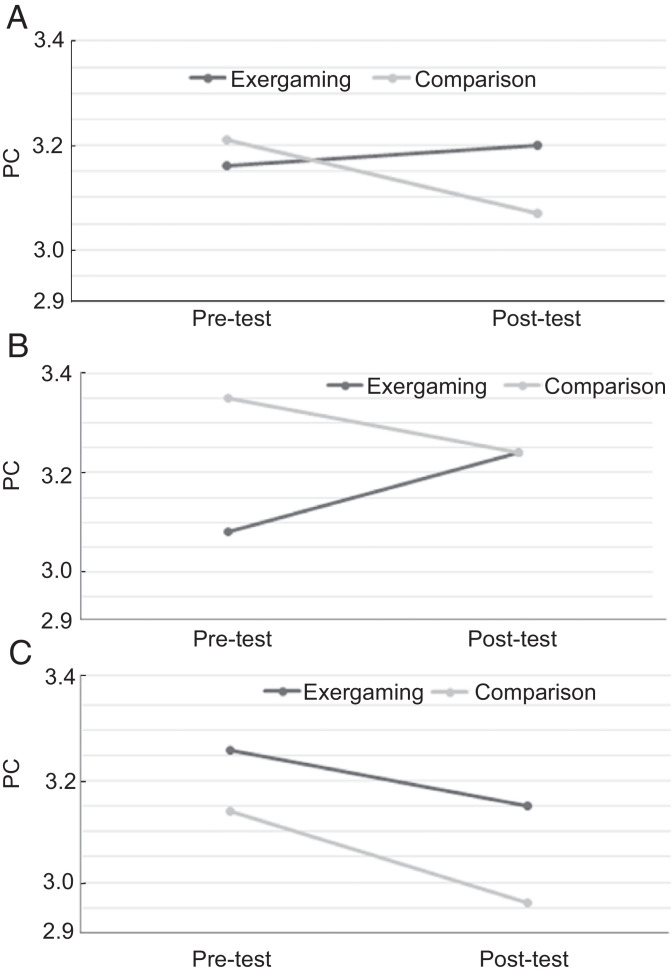

As shown in Fig.1A, a small, yet significant, Group × Time interaction for MVPA was observed (F(1, 52) = 4.37, p = 0.04, = 0.04), but there were no significant interaction effects for MSC (F(1, 52) = 0.02, p = 0.88, = 0.00) (Fig.2A), or PC (F(1, 52) = 0.83, p = 0.37, = 0.02) (Fig.3A). In detail, intervention children had significantly greater increased percentage of time in MVPA than those in the comparison group with small effect size. Moreover, there were no significant interaction effects of Group × Gender × Time or Gender × Time for any variables. Although the intervention children displayed greater increased PC and MSC at post-test than the comparison children (Table2), these improvements versus comparison did not reach statistical significance.

Fig.1.

Changes of preschoolers’ moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) over time for the whole sample (A) and by genders (B for boys, C for girls).

Fig.2.

Changes of preschoolers’ motor skill competence (MSC) over time for the whole sample (A) and by genders (B for boys, C for girls).

Fig.3.

Changes of preschoolers’ perceived competence (PC) over time for the whole sample (A) and by genders (B for boys, C for girls).

A significant time effect was observed for MSC (F(1, 52) = 15.61, p < 0.01, = 0.23) (Fig.2A), but not MVPA (F(1, 52) = 0.23, p = 0.64, = 0.01) (Fig.1A), or perceived competence (F(1, 52) = 0.37, p = 0.54, = 0.02) (Fig.3A). Further, there was no significant group effect for any variable. Of note, asignificant gender effect was observed for MVPA, (F(1, 52) = 5.06, p = 0.02, = 0.09) (Fig.1B and 1C). Specifically, boys demonstrated higher MVPA than girls at both timepoints (Table2). Gender effects were not observed for MSC (F(1, 52) = 1.15, p = 0.29, = 0.02) (Fig.2B and 2C), or PC (F(1, 52) = 0.74, p = 0.39, = 0.01) (Fig.3B and3C).

4. Discussion

Exergaming has been increasingly integrated into various school-based programs owing to its potential to promote PA among children,24, 27, 28, 59 yet no known studies are available investigating exergaming's effects on preschool children's PA, MSC, and PC. This study attempted to fill this knowledge gap. Study observations suggested that intervention children had a small yet significantly greater increased percentage of time in MVPA during the intervention versus comparison, while also demonstrating nonsignificant yet greater increased PC and MSC at post-test than at baseline versus comparison children.

The observation regarding exergaming's effect on MVPA is congruent with several previous studies,24, 27, 28, 60 suggesting positive effects of exergaming on youths’ PA levels. For instance, Gao etal.24 recently reported that a school-based exergaming program promoted the objectively determined daily MVPA of children 7–10years old over a 2-year period. It is posited that exergaming's fun and entertaining nature lead to such positive effects.27, 28, 42, 60 This finding is notable because PA enjoyment has been observed to be predictive of children's PA.23, 27, 28, 32 Future research should investigate preschool children's perceived enjoyment during exergaming versus comparison modes of PA, with follow-up examination in later years of school (e.g., first or second grade) to discern whether the potentially greater enjoyment of exergaming promotes higher daily PA in later childhood.

Similar to the observations for MVPA, increases in MSC and PC were observed among the intervention children during the intervention versus comparison. Despite the nonsignificance of these increases, such trends provide initial evidence for exergaming's positive effect on these outcomes, particularly regarding PC, because the increased PC among intervention children was accompanied by decreases in this variable among comparison children. These observations echo those of previous studies20, 27, 43, 44 and a recent study indicating exergaming's positive effect on PC in children with autism.21 Notably, the lack of significance may have been attributable to the short intervention duration, along with other factors such as small sample size and overall PA dose. Hence, longer exergaming intervention periods among preschool children is highly recommended in the future. Taken together, these observations are the first of their kind in exergaming studies among preschoolers and are encouraging given the fact that greater increases in MVPA, MSC, and PC through exergaming may aid in long-term PA participation and subsequent health promotion.27, 44

Unsurprisingly, preschoolers’ MSC significantly improved from baseline to the 8th week regardless of group and gender affiliations. This observation is consistent with those of previous studies of preschool children.15, 16 Several reasons may account for MSC increases in the present study: (1) it may improve as they age, (2) both intervention and comparison children engaged in PA (i.e., exergaming or recess) during the intervention period and thus their MSC may have improved simply owing to PA participation, and (3) MSC scores improved partially owing to a learned effect at the follow-upMSC assessments.44 Notably, however, the whole sample's MVPA and PC did not improve significantly across time, because greater increases were observed in intervention children, suggesting PA modality (exergaming vs. recess) did influence these outcomes to some degree.

Finally, a significant gender effect for preschool children's MVPA was observed, with boys demonstrating greater MVPA than girls across time. This observation mirrors that of Gao6 in that gender differences in PA were identified in older children during exergaming play. It is noteworthy that, in the current study, the intervention children rotated gameplay stations and engaged in various sports and dance games throughout the 8-week intervention. Hence, the significant gender difference observed may be partially attributable to the child perceiving a game as more or less gender appropriate (e.g., a girl may not be as motivated to play a sport game as a dance game). Indeed, it is plausible that a gender gap may begin in the preschool years. However, no gender differences in MSC and PC were identified, which are incongruent with observations in studies with older children.45, 46, 47, 48 Future research is needed among preschool-age populations to further examine these trends. Nonetheless, this study's observations do provide new, much-needed empirical evidence on the gender differences in MSC and PC among preschool children.

The present study's observations shed light on the practical implications of integrating exergaming within a school-based setting among preschoolers. First, exergaming could be considered an alternative component for school-based PA programs among preschool children. Indeed, exergaming, with its entertaining and active nature, might help young children to become more physically active while also having fun—components few other traditional PA modalities offer. Also, exergaming's enjoyable nature may lead to children's long-term PA adherence.23, 27 Thus, educators and health professionals might integrate exergaming into the school's overall curriculum to replace some school-time sedentary activities for preschool children. Additionally, exergaming demonstrates the potential to improve PC and MSC in preschool children. It is recommended that longer-term exergaming interventions be adopted to fully elucidate whether these positive initial trends in MSC and PC can be built on. Finally, the gender differences in MVPA, regardless of group affiliation, also indicate that more gender-appropriate activities may be offered to girls regardless of PA modality, with the goal of decreasing the gender gap in PA participation.

This study had the following strengths: (1) it was the first known study to integrate exergaming, a novel and enjoyable PA modality, into school-based curriculum among preschool children; (2) intervention fidelity was ensured at school settings via process evaluation, such as biweekly surveys about implementation, dose, and fidelity as well as student engagement; and (3) a large number of underserved children of minority and low socioeconomic status were targeted. Nevertheless, the study is limited in the following ways. First, participants came from only 2 underserved urban schools, with the sample size being modest, which limits the generalizability of the study observations. Consequently, a larger sample of multiple school sites should be targeted in the future. Second, in the current study, only preschool children's time in MVPA during school hours was captured, thus missing the important implications an intervention of this type may have on PA outside of school. Future research should use the same objective instruments to assess preschool children's daily PA levels. Additionally, although strict intervention fidelity protocol was used during this study, it is noteworthy that the intervention length was relatively short. Longer but similar high-quality interventions are recommended for future studies. Finally, the intervention was executed with school as the experimental unit, with randomization at the individual level not adopted owing to the inability to randomize children to different classrooms. Hence, researchers could not control for some threats to this study's internal validity, for example, the history threat of afterschool PA programs. In the future, a group randomized controlled trial with multiple schools as experimental sites may be used to minimize the internal validity threats.

5. Conclusion

The current study's observations shed new light on exergaming's impact on preschool children's PA, MSC, and PC when compared with usual care (recess) practice. Indeed, exergaming demonstrated a positive effect in promoting preschool children's MVPA at school and has the potential to enhance MSC and PC. More quality studies are called for to discern exergaming's role in improving PA and other health indices61 among underserved preschool children.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (No. 1R56HL130078-01).

Authors’ contributions

ZG conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, carried out the study, and drafted the manuscript; NZ performed the data collection/sorting and helped to draft the manuscript; ZCP helped to collect data and draft the manuscript; RW helped with the data analysis and helped to draft the manuscript; FY helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.Ogden C.L., Carroll M.D., Kit B.K., Flegal K.M. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson M.C., Gordon-Larson P. Physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns are associated with selected adolescent health risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1281–1290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden C.L., Carroll M.D., Curtin L.R., McDowell M.A., Tabak C.J., Flegal K.M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon-Larsen P., Adair L., Popkin B. US adolescent physical activity and inactivity patterns are associated with overweight: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Obesity Res. 2002;10:141–149. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y., Park I., Kang M., Mufreesboro T.N. Physical activity and sedentary behavior trends of US children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2012;83(Suppl.1) A71. doi: 10.1080102701367.2012.10599840. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Z. Growth trajectories of young children's objectively determined physical activity, sedentary behavior, and body mass index. Childhood Obesity. 2018;14:259–264. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Association for Sport and Physical Education. Active Start: a statement of physical activity guidelines for children birth to five years . NASPE Publications; Reston, VA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics and Councils on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Council on School Health Active healthy living: prevention of childhood obesity through increased physical activity. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1834–1842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonis M., Loftin M., Ward D., Tseng T.S., Clesi A., Sothern M. Improving physical activity in daycare interventions. Childhood Obesity. 2014;10:334–341. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliakim A., Menet D., Balakirski Y., Epstein Y. The effects of nutritional-physical activity school-based intervention on fatness and fitness in preschool children. J Pediatr Endocrunal Metab. 2007;20:711–718. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2007.20.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puder J.J., Marques-Vidal P., Schindler C., Zahner L., Niederer I., Bürgi F. Effect of multidimensional lifestyle intervention on fitness and adiposity in predominantly migrant preschool children (Ballabeina): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d6195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgibbon M.L., Stolley M.R., Schiffer L., Van Horn L., Kaufer-Christoffel K., Dyer A. Two-year follow-up results for Hip-Hop to Health Jr.: a randomized controlled trial for overweight prevention in preschool minority children. J Pediatr. 2005;146:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen X., Zhang Y., Gao Z., Zhao W., Jiang J., Bao L. Effect of mini trampoline physical activity on executive functions in preschool children. Biomed Res Int. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2712803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly J.J., McDowell Z.C. Physical activity interventions in the prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: systematic review and critical appraisal. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:611–619. doi: 10.1079/PNS2003265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellows L.L., Davies P., Anderson J., Kennedy C. Effectiveness of a physical activity intervention for head start preschoolers: a randomized intervention study. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67:28–36. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mativinko O., Ahrabi-Fard I. The effects of a 4-week after-school program on motor skills and fitness of kindergarten and first-grade students. Sci Health Promot. 2010;24:299–303. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.08050146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng N., Ayyub M., Sun H., Wen X., Xiang P., Gao Z. Effects of physical activity on motor skills and cognitive development in early childhood: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2760716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulteen R.M., Ridgers N.D., Johnson T.M., Mellecker R.R., Barnett L.M. Children's movement skills when playing active video games. Perce Motor Skills. 2015;121:767–790. doi: 10.2466/25.10.PMS.121c24x5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnett L.M., Ridgers N.D., Reynolds J., Hanna L., Salmon J. Playing active video games may not develop movement skills: an intervention trial. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett L.M., Bangay S., McKenzie S., Ridgers N. Active gaming as a mechanism to promote physical activity and fundamental movement skill in children. Front Public Health. 2013;1:74. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards J., Jeffrey S., May T., Rinehart N.J., Barnett L.M. Does playing a sports active video game improve object control skills of children with autism spectrum disorder? J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stagnitti K., Kershaw B., Malakellis M., Kershaw B., Hoare M., De S. Evaluating the feasibility, effectiveness and acceptability of an active play intervention for disadvantaged preschool children: a pilot study. Austral J Early Child. 2011;36:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Z., Chen S. Are field-based exergames useful in preventing childhood obesity? A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:676–691. doi: 10.1111/obr.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Z., Pope Z., Lee J.E., Stodden D., Roncesvalles N., Pasco D. Impact of exergaming on young children's school day energy expenditure and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Z., Hannon J.C., Newton M., Huang C. Effects of curricular activity on students’ situational motivation and physical activity levels. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2011;82:536–544. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2011.10599786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao Z. Motivated but not active: the dilemmas of incorporating interactive dance into gym class. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:794–800. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.6.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Z., Chen S., Pasco D., Pope Z. Effects of active video games on physiological and psychological outcomes among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:783–794. doi: 10.1111/obr.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyons E.J., Tate D.F., Ward D.S., Ribisl K.M., Bowling J.M., Kalyanaraman S. Engagement, enjoyment, and energy expenditure during active video game play. Health Psych. 2014;33:174–181. doi: 10.1037/a0031947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Z., Hannan P.F., Xiang P., Stodden D., Valdez V. Effect of active video game based exercise on urban Latino children's physical health and academic performance. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harter S. A model of intrinsic mastery motivation in children: individual differences and developmental change. In: Collins A., editor. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. (Minnesota symposium on child psychology). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Dev. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao Z. The role of perceived competence and enjoyment in predicting students’ physical activity levels and cardiorespiratory fitness. Percept Motor Skills. 2008;107:365–372. doi: 10.2466/pms.107.2.365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnett L.M., Morgan P.J., van Beurden E., Ball K., Lubans D.R. A reverse pathway? Actual and perceived skill proficiency and physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:898–904. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fdfadd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnett L.M., Morgan P.J., van Beurden E., Beard J.R. Perceived competence mediates the relationship between childhood motor skill proficiency and adolescent physical activity and fitness: a longitudinal assessment. Inter J Behav Nutri Phys Act. 2008;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hands B. Changes in motor skill and fitness measures among children with high and low motor competence: a five-year longitudinal study. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopes V., Rodrigues L., Maia J., Malina R.M. Motor coordination as predictor of physical activity in childhood. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staiano A.E., Beyl R.A., Hsia D.S., Katzmarzyk P.T., Newton R.L., Jr Twelve weeks of dance exergaming in overweight and obese adolescent girls: transfer effects on physical activity, screen time, and self-efficacy. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope Z., Lewis B., Gao Z. Using the Transtheoretical Model to examine the effects of exergaming on physical activity among children. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:1205–1212. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maddison R., Mhurchu C.N., Jull A., Jiang Y., Prapavessis H., Rodgers A. Energy expended playing video console games: an opportunity to increase children's physical activity? Pedia Exerc Sci. 2007;19:334–343. doi: 10.1123/pes.19.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanningham-Foster L., Foster R.C., McCrady S.K., Jensen T.B., Mitre N., Levine J.A. Activity-promoting video games and increased energy expenditure. J Pediatrics. 2009;154:819–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Z., Podlog L., Huang C. Associations among children's situational motivation, physical activity participation, and enjoyment in an active dance video game. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Z., Zhang T., Stodden D.F. Children's physical activity levels and their psychological correlated in interactive dance versus aerobic dance. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:146–151. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Z., Huang C., Liu T., Xiong W. Impact of interactive dance games on urban children's physical activity correlates and behavior. J Exerc Science Fit. 2012;10:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng Z., Gao Z. Effects of exergaming and fundamental movement skills among youth and young adults: a systematic review. In: Hogan L, editor. Gaming: trends, perspectives and impact on health. Nova Science Publishers; Hauppauge, NY: 2016. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodway J.D., Branta C.F. Influence of a motor skill intervention on fundamental motor skill development of disadvantaged preschool children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2003;74:36–46. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2003.10609062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodway J.D., Savage H., Ward P. Effects of motor skill instruction on fundamental motor skill development. Adap Phys Act Q. 2003;20:298–314. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiang P., McBride R., Guan J. Children's motivation in elementary physical education: a longitudinal study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2004;75:71–80. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2004.10609135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiang P., McBride R., Bruene A. Fourth graders’ motivational changes in an elementary physical education running program. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006;77:195–207. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan X., Cao Z.B. Physical activity among Chinese school-aged children: national prevalence estimates from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China-The Youth Study. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper A.R., Goodman A., Page A.S., Sherar L.B., Esliger D.W., van Sluijs E.M. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children's accelerometry database (ICAD) Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vazou S., Mantis C., Luze G., Krogh J.S. Self-perceptions and social-emotional classroom engagement following structured physical activity among preschoolers: a feasibility study. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butte N.F., Wong W.W., Lee J.S., Adolph A.L., Puyau M.R., Zakeri I.F. Prediction of energy expenditure and physical activity in preschoolers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;4:1216–1226. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trost S.G., Mciver K.L., Pate R.R. Conducting accelerometer-based activityassessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:531–543. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ulrich D.A. 2nd ed. Pro-Ed; Austin, TX: 2000. Test of gross motor development. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harter S., Pike R. The pictorial scale for perceived competence and social acceptance for young children. Child Dev. 1984;55:1969–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harter S. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1985. The self-perception profile for children. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harter S. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1999. The construction of the self: a developmental perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richardson J. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ Res Rev. 2011;6:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao Z. Fight fire with fire: promoting physical activity and health through active video games. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pasco D., Roure C., Kermarrec G., Pope Z., Gao Z. The effects of a bike active video game on players’ physical activity and motivation. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baranowski T. Exergaming: hope for future physical activity? or blight on mankind? J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]