Abstract

Investigations of most riboswitches remain confined to the ligand-binding aptamer domain. However, during the riboswitch mediated transcription regulation process, the aptamer domain and the expression platform compete for a shared strand. If the expression platform dominates, an anti-terminator helix is formed, and the transcription process is active (ON state). When the aptamer dominates, transcription is terminated (OFF state). Here, we use an expression platform switching experimental assay and structure-based electrostatic simulations to investigate this ON-OFF transition of the full length SAM-I riboswitch and its magnesium concentration dependence. Interestingly, we find the ratio of the OFF population to the ON population to vary non-monotonically as magnesium concentration increases. Upon addition of magnesium, the aptamer domain pre-organizes, populating the OFF state, but only up to an intermediate magnesium concentration level. Higher magnesium concentration preferentially stabilizes the anti-terminator helix, populating the ON state, relatively destabilizing the OFF state. Magnesium mediated aptamer-expression platform domain closure explains this relative destabilization of the OFF state at higher magnesium concentration. Our study reveals the functional potential of magnesium in controlling transcription of its downstream genes and underscores the importance of a narrow concentration regime near the physiological magnesium concentration ranges, striking a balance between the OFF and ON states in bacterial gene regulation.

INTRODUCTION

Decades of research have elucidated cellular responses to stimuli in terms of interactions between various transcription factors, RNA polymerase or other associated proteins, which often exert allosteric effects on their regulatory targets. Only quite recently, riboswitches have been recognized as important players in controlling bacterial gene expression, namely a class of non-coding RNA elements located in the untranslated 5′ stretch of certain bacterial messenger RNAs (mRNA) (1–4). The control is often exerted via the level of cellular metabolites that self-regulate their production, binding directly to a riboswitch motif on the mRNA that encodes enzymes involved in their biosynthesis. Riboswitches can be configured to be either ON- or OFF-switches. Here, metabolite binding stabilizes a conformation involving the riboswitch aptamer domain over an alternate structure that either interferes with or allows mRNA transcription or its translation (5). For example, SAM (S-adenosyl methionine) riboswitches bind SAM to regulate SAM and methionine biosynthesis (2). SAM is an effective methyl donor in a myriad of biological and biochemical processes as essential as ATP processing (6–8).

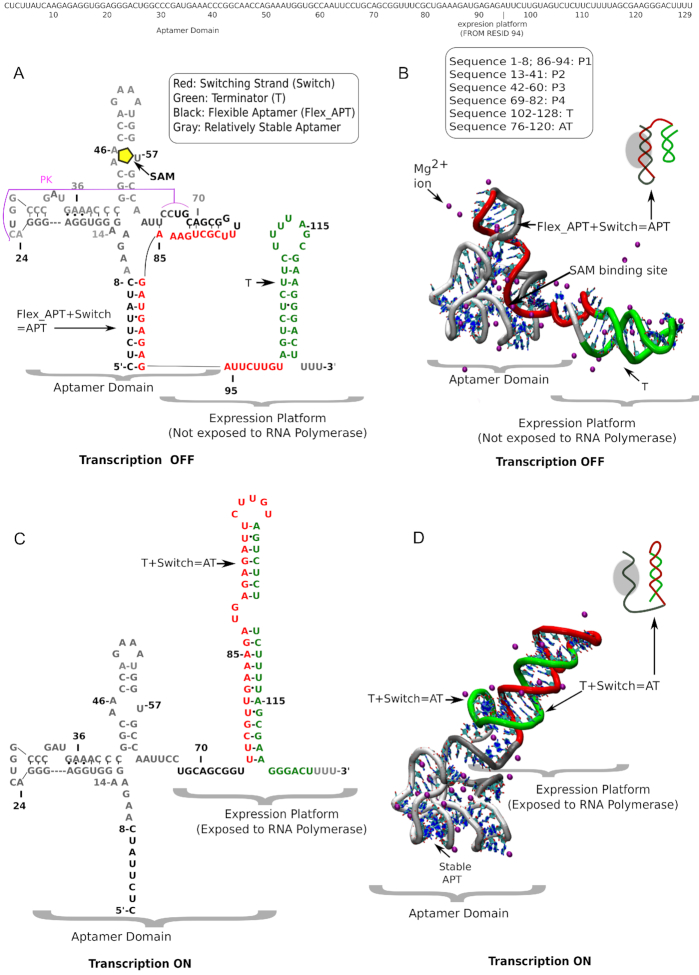

Like most other riboswitches, the SAM-I riboswitch contains two partially overlapping domains: (i) the aptamer and (ii) the expression platform (EP). In order to control transcription a shared strand can form interactions either with the aptamer or with the EP (3,9–11) (Figure 1). In the absence of metabolite, the EP incorporates the shared strand, forming an anti-terminator (AT) helix which allows the RNA polymerase to continue the transcription process (AT/ON state). A relatively stable segment of the aptamer forms a ligand binding site that serves to sense the metabolite, while a flexible segment competes with the EP for the shared strand. When the metabolite becomes bound to the aptamer domain, the shared strand is held by the aptamer, while the rest of the EP transitions into a terminator helix, inhibiting the access of RNA-polymerase and aborting transcription (APT/OFF state). This apparently simple mechanism of riboswitch mediated transcriptional regulation is complicated by its dependence on many complex processes like folding, ligand recognition and magnesium ion (Mg2+) mediated interactions (12–15). In particular, the riboswitch can work effectively only if the rate of folding and the rate of ligand recognition become at least comparable with the rate of transcription (16,17). In our previous studies of the SAM-I riboswitch, and also for other riboswitches, we have shown that Mg2+ ions play an important role in accelerating folding by lowering the barrier for pre-organization (18,19). During pre-organization, RNA forms a binding competent conformation that allows rapid detection of ligand with high selectivity (20).

Figure 1.

Secondary and tertiary structure of full-length SAM-I riboswitch (with sequence) in SAM-bound transcription OFF state and SAM-free transcription ON state. (A) Sequence-aligned secondary structure and (B) tertiary structure of the transcription OFF state of SAM-I riboswitch in the presence of metabolite, SAM (yellow pentagon) surrounded by explicit magnesium ions (purple). Different secondary structural segments are defined sequence-wise. Note the partially overlapped aptamer and EP (EP) domains. (C) Sequence-aligned secondary structure and (D) tertiary structures of the transcription ON state surrounded by explicit magnesium (purple) ions. Four characteristic segments, important for switching, are designated with distinct colors: Red: switching strand; green: terminator helix in the EP domain; black: flexible aptamer; gray: more stable aptamer. In the transcription OFF state the flexible aptamer owns the red switching strand. In the transcription ON state green terminator sequesters the red switching strand.

To date, investigations of the SAM-I riboswitch have mostly remained limited to the aptamer domain due to a lack of structural information for the complete system (16,21–25). X-ray crystallography has provided the structures for the ligand-bound aptamer domain of the SAM-I riboswitch from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis (26) and Bacillus subtilis yitJ (27), but even this part is rather underexplored computationally because of the difficulty in sampling the conformational landscape of such a complex system at a high level of description and in full atomistic detail. Thus, in order to understand the metabolite recognition process microscopically, we have initially used simulations with a basic all-atom structure-based model (SBM) to characterize the folding, unfolding, and metabolite binding of the aptamer domain. As an initial insight into the regulation of the EP, our results showed how the metabolite, SAM, assists in folding of the P1 helix by reducing the associated free energy barrier. To explore the RNA energy landscape with quantitative accuracy and to account for the ion atmosphere of associated Mg2+ surrounding the RNA, we have recently developed a Generalized Electrostatic Model (GEM) and incorporated it into structure based molecular dynamics simulations (21). Using atomistic simulations with our newly developed GEM potential earlier we have explored the free energy landscape of the SAM-I aptamer in the presence and the absence of ligand, SAM (19). While we observed that SAM efficiently stabilizes the flexible P1-helix by connecting it with the P3-helix, in the absence of SAM, Mg2+ ions already substantially stabilize the pseudoknot and the flexible P1 and P4 helices and pre-organize the aptamer.

A tremendous research opportunity exists both experimentally and computationally to investigate the poorly understood mechanism of ligand-induced switching and the associated role of Mg2+ at a molecular level. Thus, to monitor the details of the transcriptional control mechanism of the full-length SAM-I riboswitch, we have already performed a switching assay experiment using a separate EP template (23). An earlier switching assay and results from a variety of structural probing experiments have identified the key tertiary interactions that are present in a state that is partially collapsed by Mg2+ ions, before the presence of metabolite shifts the equilibrium towards a more collapsed state (24,28,29). All these previous studies focus on pre-organization of the aptamer domain, to which SAM binds. Without adequate structural information, one can, however, not rule out a possible role of the EP in aptamer pre-organization. A very recent smFRET study by Nienhaus and co-workers, which explored the conformational landscape of the full length SAM-I riboswitch, is consistent with our early switching assay experiment (30). This study showed that the anti-terminator helix becomes more stabilized at high Mg2+ concentration, and the binding of SAM gradually shifts the population towards the terminator states. Their analysis, however, indicated further that the aptamer is substantially folded also at low Mg2+ concentrations, and even in the absence of Mg2+. This state appeared at a FRET efficiency ∼0.3. This aspect is somewhat contradictory to earlier smFRET results by Lafontaine and co-workers, obtained for the aptamer domain only but probed near the same locations, where a FRET efficiency of 0.3 corresponds to an unfolded ensemble in the absence of Mg2+ (31). Very recently, Nienhaus and co-worker have extended their previous analysis probing another location, which is in the P4 helix region, as their earlier Gaussian distributions corresponding to each conformation were mutually overlapped (32). With the new FRET-labeled variant their new analyses reveal five states instead of their early four-state model. We understand that it is extremely challenging to separate different Mg2+ induced complex states by a FRET based non-collective order parameter. Moreover, it would always depend on the probe location, which might appear insensitive to capture the collective nature of the conformational landscape distinguishing each state. Therefore, in order to capture the hierarchical conformational free energy landscape, rigorous thermodynamic calculations considering suitable collective reaction coordinates are of utmost importance to understand the functioning of full-length SAM-I riboswitch in microscopic detail. For example, in constructing a full-length secondary structural model of SAM-I, Nienhaus and co-worker posit that only the 3′ end of P1 helix is the shared sequence between the aptamer domain and the anti-terminator platform (30,32), while our early electrophoretic mobility shift assays indicated that the range of anti-terminator formation extends from the 3′ portion of P1 to the flexible smallest helix, P4 (20). We have verified this from our early thermodynamic calculations (19). Another study, related to transition rate limited free folding of SAM-I riboswitch, also found such highly flexible behavior of P4 (33), which might become a prerequisite to forming a stable extended anti-terminator at Mg2+ concentrations that are suitable to activate the transcription process in the absence of SAM. Due to lack of appropriate structural and thermodynamic characterization, it is hard to discern the effect of Mg2+ on the aptamer pre-organization in the full-length SAM-I riboswitch at low Mg2+ concentrations, below the physiological range. Yet, all early studies raise many interesting and important questions, such as, why does the anti-terminator helix preferentially gain stability with higher [Mg2+]? What is the extent of aptamer collapse that remains unaffected when the anti-terminator forms? Does this collapse affect aptamer pre-organization and SAM-induced transcription OFF control? To answer these questions and to understand the complex interplay between the aptamer and EP domains that directly affects transcription ON-OFF control for the full length SAM-I riboswitch, first we studied the switching from an electrophoretic mobility shift assay where the flexible switching strand of the aptamer domain is challenged with an oligomeric complementary strand (RNA/DNA chimera of 2′-O-methyl RNA and DNA residues). Depending on the surrounding magnesium ion environment this switching part either detaches from the aptamer or stays with the aptamer as per their thermodynamic stability. When this switching part finds its complementary strand, it forms the anti-terminator analogue by base-paring. As folding of the full-length SAM-I construct is a rather complex phenomenon, this experimental strategy not only mimics the structural characteristics of the full-length SAM-I riboswitch, at length, but also made the domain-specific interactions and domain-domain competition for the switching strand controllable and easier to understand. In order to microscopically understand the magnesium sensitivity of the switching and the thermodynamic basis of our experimental findings, we have constructed in this work an all atom full length (aptamer+EP) model of SAM-I riboswitch, following the same sequence and base-pairing information for the EP as we used in our previous switching assay experiment (23).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed to quantify the extent of anti-terminator formation between the aptamer domain and an analog of the EP. The aptamer domain was based on the T. tengcongensis Met F sequence: (agc gac ugc acu uug acg cuc gac auu acu cuu auc aag aga ggu gga ggg acu ggc ccg aug aaa ccc ggc aac cag ccu uag ggc aug gug cca auu ccu gca gcg guu ucg cug aaa gau gag ag a uuc uug ugg cau gcu c). RNA was transcribed from PCR derived templated using T7-RNA polymerase. Aptamer domain RNA was first folded at various concentrations of MgCl2 and then challenged with a RNA oligo (5′-rGrArA rUrCrU rCrUrC rArUrC rUrUrU rCrArG rCrGrA rA-3′) containing sequence elements from the native riboswitch EP. The aptamer (0.5 μM) is folded by first heating to 90°C in water for 2 minutes, placing on ice for 2 minutes followed by the addition of buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 100 mM KCl, 80 μM SAM and various concentrations of MgCl2 (100 μM, 400 μM, 1 mM, 2 mM, 4 mM, 10 mM, 50 mM and 100 mM). The aptamer RNA is then equilibrated for 10 min at 37°C, mixed with the oligomer (250 nM aptamer, 1 μM oligomer to insure that when the switching takes place, the aptamer is saturated with the switching strand) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction is stopped by dilution into cold H2O (1:10 000) for analysis by capillary electrophoresis. Non-denaturing media for capillary electrophoresis was made by the polymerization of N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA, Sigma-Aldrich). A 5% (v/v) solution (10 ml) of DMA was made in 1× TBE and polymerized by the addition of 10 μl TEMED and 100 μl of ammonium persulfate. The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. Sybr-Gold (Invitrogen) was added to polymerized DMA (1:1 × 106) to resolve the RNA on an Applied Biosystems 310 instrument. 20 μl of the diluted reaction was injected at 6 kV for 30 s and electrophoresed for 30 minutes at 12 kV. Data was analyzed using in house scripts to fit Gaussian peaks for integration. After integration, the extent of switching is expressed as the ratio between the peak area of the free aptamer domain (transcription OFF) over the peak area of the aptamer–EP complex (transcription ON). Errors bars are the standard deviations between experiments.

Minimal model construction for full length SAM-I ribswitch

As we mentioned earlier, in the presence of SAM, the aptamer domain acquires the switching strand and forms the transcription OFF state, while in the absence of SAM, the EP incorporates the switching region, forming the anti-terminator (AT) helix and the transcription ON state. Based on our early sequence information combined with secondary and tertiary structural data collected from X-ray crystallography, chemical probing by Selective 2′-Hydroxyl Acylation analyzed by Primer Extension (SHAPE) and Nucleotide Analog Interference Mapping (NAIM) experiments that separate the SAM-free and the SAM-bound conformations, we have developed model constructs for the transcription ON state and the transcription OFF state (Figure 1) (26,34,35). Both the simulations and experiments for this study used T. tencongensis Met F aptamer. Crystal structures of the aptamer domain of Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, both in its SAM-bound (pdb: 2GIS) and SAM-unbound (3IQP) forms are available that distinguish slight conformational changes in the SAM binding site that have been taken into account in our model construct. We have discussed the details of this conformational change as Supplementary Data. In the OFF state, where the aptamer domain is fully formed, our simulation obtained most of the required aptamer structural information from 2gis.pdb (26). In the ON-state, the aptamer domain is partially formed as the switching segment is then already migrated to the EP. Our early EP switch assay experiment helped us to assess the length of this switching element migrating from the aptamer to the EP (20). The important segments that help to characterize the switching are distinguished in Figure 1. The expression platform structures for both transcription OFF and transcription ON states are built using the MacroMolecule Builder (MMB) software package (34), consistently following our early experimental base-pairing information. Using these two structural constructs, a dual-basin structure-based model (SBM) Hamiltonian has been derived to investigate the switching between the transcription ON state and the transcription OFF state. Also, in order to study the Mg2+ effect on the transcription ON-OFF switching mechanism, we have implemented our GEM potential in the context of our dual-basin structure SBM Hamiltonian. In this work, we have first performed SHAPE probing experiments and single-basin SBM electrostatic simulations on the aptamer domain to understand its separate [Mg2+]-dependent collapse transition. Then, we systemically move forward to our EP switching assay experiment and dual basin SBM electrostatic simulations for the full-length SAM-I riboswitch to understand the transcription ON-OFF switching mechanism and associated Mg2+ effects. Other model construction details are given as Supplementary Data.

Potential for structure-based Generalized Electrostatic Model (GEM) simulation

Our structure-based GEM potential treats Mg2+ ions explicitly to capture explicit RNA–Mg2+ interaction and represents KCl buffer implicitly to make the potential computationally economical (21). In order to deal with implicit-explicit charge interaction we have implemented our recently developed electrostatic model into our all-atom structure based potential. The implicit behavior of KCl has been treated using generalized Manning condensation theory that also includes Manning condensed charge and Debye screening charge interactions especially developed to characterize RNA electrostatics and works for general RNA geometries. Thus, the overall Hamiltonian includes three terms as shown in Equation (1):

|

(1) |

where HSBM contains harmonic potentials that restrain the bonds, angles, and improper/planar and proper/flexible dihedral angles. HExcl is the excluded volume effect for the explicit hexa-hydrated Mg2+ ions. HElec contains all types of charge interactions using Generalized Manning condensation theory that is elaborated in the Supplementary Data. This model was calibrated against experimental measurements of the excess Mg2+ associated with the RNA, which characterizes the Mg2+–RNA interaction free energy. The model was further tested on the SAM-II riboswitch system against several experimental results derived from recent experimental studies, using 13C-chemical exchange saturation transfer (13C-CEST), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET), and size-exclusion chromatography (18). All these experiments and our GEM simulations jointly quantified the effect of Mg2+ ions in the pre-organization of the SAM-II riboswitch, a phenomenon that has also been observed in other riboswitches, such as the SAM-I, pre-Q, adenine, and THI-box riboswitches (36–40). We also predicted that the pre-organized state of the SAM-II riboswitch is incrementally stabilized by addition of magnesium only up to a threshold concentration of magnesium. Beyond this critical concentration, additional Mg2+ cannot be incorporated into the inner 1st layer of Mg2+ solvation of the RNA. This maximum effective Mg2+ concentration in the pre-organized state can only induce a partial collapse of the RNA; ligand association is required for complete collapse into the functional fold (18).

Folding energy landscape calculation

To study the folding energy landscape of RNA, we use models, developed from energy landscape theory, that consider the native state as the global minimum in the landscape but allow structural excursions, up to complete unfolding (41,42). In a single basin SBM, the crystal structure of the folded RNA is the native state from which we obtain all the initial bonds, angles, and improper/planar and proper/flexible dihedral information. Lennard Jones' 6–12 potential form is used to treat the non-local pair-interactions present in the native crystal structure while all other, non-native pair-interactions present are repulsive. The potential form of the single basin SBM and all the necessary parameters are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. Long time equilibrium simulations were performed to evaluate equilibrium average physical quantities, such as radius of gyration, theoretical SHAPE reactivity, to name a few. For folding free energy calculation we used Umbrella Sampling and Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (43,44). Equilibrium simulation details and Umbrella Sampling details are given in the Supplementary Data.

RNA dual-basin energy landscape calculation

While in single-basin SBM, a unique native structural fold is considered as the global minimum, in dual basin energy landscapes (43–47), two stable structural folds are considered as two possible energy minima. To investigate the conformational transition between these two minima, in this work we developed a dual-basin structure-based model. During all dual-basin electrostatic model simulations we have used our dual-basin structure-based potential HDB–SBM instead of canonical HSBM in Equation (1). The dual-basin free energy landscapes for the transition between two different folds at different Mg2+ concentrations are also calculated using Umbrella Sampling and Weighted Histogram Analysis Method. Dual-basin Hamiltonian and the relevant parameters for transition free energy calculations are given in the Supplementary Data.

SHAPE probing experiment

RNA samples were folded as described above using HMK buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, with varying concentrations of MgCl2) and 100 μM SAM (NEB). The RNA (final concentration, 0.5 μM) was equilibrated at 37°C for 10 min and cooled to 25°C. 1/10th volume of 1M7 (1-methyl-7-nitroisatoic anhydride, 60 mM in DMSO) is added to the sample and the reaction was incubated for 5 minutes at 25°C. RNA is then precipitated by the addition of 3 volumes absolute ethanol, 1/10th volume 3 M sodium acetate and 25 μg glycogen (Ambion) followed by centrifugation. Aptamer RNA is then dissolved in 15 μl (1μM RNA) of primer extension mix containing 0.25 mM dNTPs, 3 pmoles of 5′-Alexa-488 labeled primer, and reverse transcriptase (200 U superscript III MMLV-RT (Invitrogen) in the supplied buffer. These reactions are incubated at 45°C for 1 h. Sequencing reactions are performed on unmodified RNA in the same manner, but the mix contains 100 μM of a ddNTP. Primer extension reactions are then desalted using a P-6 micro-biospin column (Bio-Rad) and centrifuged. The samples are lyophilized and re-suspended in highly deionized (Hi-Di) formamide for analysis. Each sample is diluted 1:20 with Hi-Di formamide and heated to 95°C for 2 min. The samples are electrokinetically injected (30 s at 6 kV) onto an ABI Prism 3100 Avant quad-capillary instrument and a fluorescence electropherogram is collected (∼60 m at 14 kV). The data is then integrated and aligned using an in-house program for the simultaneous fitting of multiple Gaussian peaks to the traces. Areas are then assigned by alignment with dideoxy-sequencing data and normalized between runs based on the constant reactivity at nucleotide U84 in the loop of P4. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times for each condition.

Theoretical SHAPE calculation

SHAPE reactivity traces backbone rigidity. In experiment, it is probed by the selective acylation at the 2′-hydroxyl position and then analyzed by primer extension (19). In our previous studies, we have shown that the corresponding backbone rigidity can be well captured by the measurement of an angle fluctuation which involves that 2′-hydroxyl group (19,48). The angle comprises of O2′ of 2′-hydroxyl group, P of the phosphate group and O5′ of ribose sugar. From this angle fluctuation, we can calculate the associated free energy change using Equation (2), which quantifies stability of each nucleotide.

|

(2) |

SHAPE reactivity is calculated from a pseudo-energy function proposed by Daigan et al. (49).

|

(3) |

Equation (3) relates the stability of a nucleotide (i) and its normalized SHAPE reactivity. The slope and the intercept were used as general parameters (49).

RESULTS

Experiments and simulations in detailed agreement reveal domain-specific monotonic and non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence

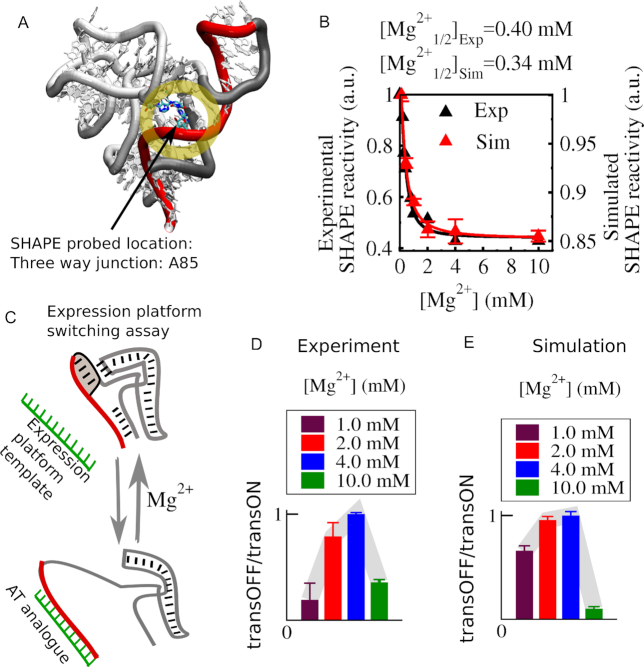

SHAPE reactivity measurement is a method to identify backbone flexibility at nucleotide resolution. In the experiment, a 2′-hydroxyl position is probed by selective acylation and then analyzed by primer extension (50). In simulation, one can calculate the normalized SHAPE reactivity per nucleotide using a pseudo-energy function (details are in the method section) (49). In previous experimental and theoretical studies, SHAPE measurement helped us to pinpoint various dynamic regions of the SAM-responsive riboswitch from T. tengcongensis (19,51). A crystal structure of the aptamer domain from B. subtilis yitJ also sheds light on possible functional implications of important tertiary interactions that influence the global fold, pre-organization and metabolite-binding (27). This study reported that helix pairs P1-P4 and P2-P3 are pairs of coaxially stacked helices linked by a four-way junction in the aptamer domain. A kink turn and a pseudoknot help to stabilize these coaxial stacks. Recently, a FRET based study has unraveled the functional implications of the P1–P4 coaxial stack that is connected via U114–A138 (28). In our study, we have traced the same connection (in the adopted sequence numbering, U64-A85, highlighted in Figure 2A) by probing nucleotide position A85. Both our experimental and computational SHAPE reactivity profiles as a function of Mg2+ concentration are consistent with each other. Both profiles are best fitted to a Hill equation which allows us to determine transition midpoint values, [Mg2+]1/2. Both [Mg2+]1/2 values indicate that the Mg2+-induced collapse transition occurs within 0.3–0.4 mM Mg2+ concentration range. Encouraged by this consistent behavior of simulations and experiment we turn to the switching of the full-length riboswitch. In order to monitor the switching, in experiment, we followed the association of an expression-platform analogue with the aptamer using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 2C). Depending on the association of the switching strand (red) either with the aptamer (gray) or with the EP (green), the possible states have been resolved by capillary electrophoresis using an intercalating fluorescent dye, Sybr-gold. The capillary electrophoresis traces from the titration of Mg2+ were fitted by a simple two-state model, from which we calculated the population ratio of the transcription OFF state to the transcription ON state. In parallel, our dual-basin SBM simulation integrated with GEM revealed additional mechanistic details of this switching process for the full-length riboswitch construct, both in the presence and absence of metabolite SAM. Our free energy calculations for this switching transition between the transcription ON and the transcription OFF states allow us to quantify the population ratio as it was extracted from our experiment. Both experimental and theoretical population profiles as a function of [Mg2+] reveal that the transcription-OFF/transcription-ON ratio is maximized at an intermediate Mg2+ concentration. In the absence of metabolite, the profile initially shows a Mg2+ induced collapse transition followed by increasing aptamer population, but only up to a Mg2+ concentration of 4.0 mM. Beyond 4.0 mM Mg2+concentration, the population of the anti-terminator helix starts to grow more than the aptamer population level, which correlates well with the recent smFRET result (30). As the population ratios from our simulations of the full-length riboswitch indeed capture the initial stabilization of the aptamer as it is revealed by our SHAPE results, we trust that our free energy calculations can also illuminate why addition of more Mg2+ beyond 4.0 mM instead hinders the growth of the aptamer population.

Figure 2.

Experimental and computational investigations of [Mg2+] dependence of aptamer domain and the same for full-length SAM-I riboswitch (aptamer+EP). (A) SHAPE probing location at the J1/4 region that connects four helices in the aptamer domain. (B) Experimental (black triangle) and simulated (red triangle) SHAPE reactivity measurements as a function of Mg2+ concentration. The data are best fitted to a Hill equation which quantifies the collapse transition midpoint, [Mg2+]1/2. Experimental and simulation measurements yield close [Mg2+]1/2 value (∼0.3–0.4 mM). (C) Schematic of experiment: EP is added to aptamer RNA for various magnesium concentrations. An RNA oligomer mimics the operation of native EP sequence, which is capable of sequestering switching strand sequence from the aptamer when the aptamer is less stable. (D) An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was used to calculate the ratio of the peak area from the aptamer in the OFF-state to the peak area for the aptamer–anti-terminator complex in the ON state as a function of [Mg2+]. (E) Theoretically computed ratio of the same was calculated from the free energy landscape of the transition between transcription ON and transcription OFF state. The population profile as a function of [Mg2+] shows non-monotonic dependence with a maximum transcription OFF state population ∼4.0 mM Mg2+.

Dual-funneled structure-based free energy calculations capture SAM-induced transcription OFF state stabilization and high [Mg2+] induced transcription ON state stabilization

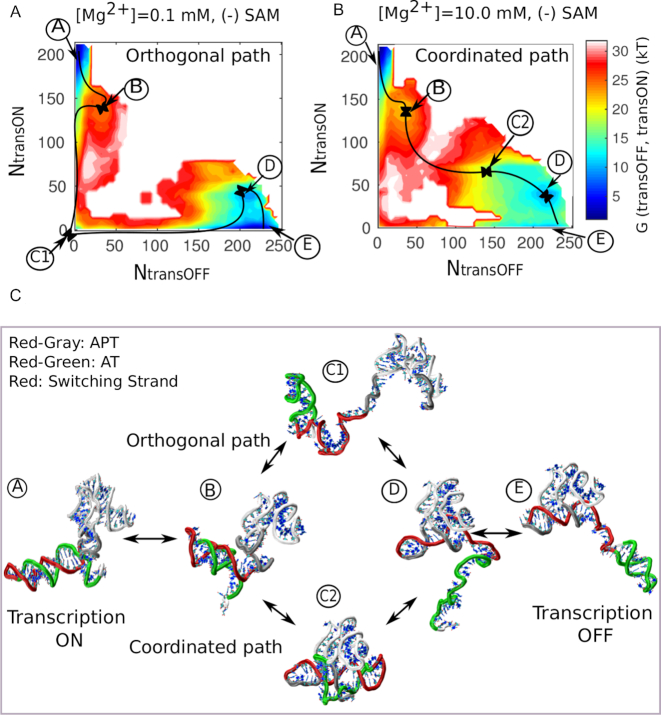

Our free energy calculations with a dual-funneled structure-based model allow us to explore all the accessible conformational pathways along the transcription ON-OFF transition of the SAM-I riboswitch at varying Mg2+ concentrations, both in the presence and in the absence of the metabolite, SAM. In this model, our reconstructed minimal models for the transcription ON and the transcription OFF states, shown in Figure 1, are treated as two competing native folds for the full-length SAM-I riboswitch. To monitor the transition between the two, we evaluate the respective numbers of formed (native) contacts that are unique to the (native) transcription OFF state or unique to the (native) transcription ON state. The difference between the numbers of these (native-) state-specific contacts serves as a suitable transition coordinate tracking the transition progress. The unique contacts corresponding to the transcription OFF-state essentially include those contacts that connect the flexible aptamer (black) and the switching strand (red). On the other hand, the unique contacts corresponding to the transcription ON state include those contacts that connect the terminator part (green) with the switching strand (red). Contacts were determined using the Shadow software (52). The free energy calculation details are given in the method section.

We plot the free energy of the system as a function of our transition coordinate to quantify the relative stability of the ON and OFF state. While the total number of exclusive contacts found in the transcription OFF state is slightly higher than that in the transcription ON state, the transition free energy shows a relative stabilization of the transcription ON state over the transcription OFF state, which maintains the character of the metabolite-free condition as found in physiological Mg2+ (2.0 mM) concentration (Figure 3A) (53–55). In the presence of 0.4 mM SAM, binding of SAM substantially stabilizes the transcription OFF state (Figure 3A). In the presence of 0.4 mM SAM, our thermodynamic calculations ensure enhanced sampling of several binding-unbinding events, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Considering 2.0 mM Mg2+ as our reference, when we calculate the transition free energy at varying Mg2+ concentrations from lower ([Mg2+] = 0.1 mM) to higher ([Mg2+] = 10.0) values (shown in Figure 3B) in the absence of metabolite, we find that the stability of the transcription OFF-state relative to the ON state (ΔGtransOFF-transON) shows a non-monotonic Mg2+ concentration dependence (inset of Figure 3B) as found in Figure 2D and E).

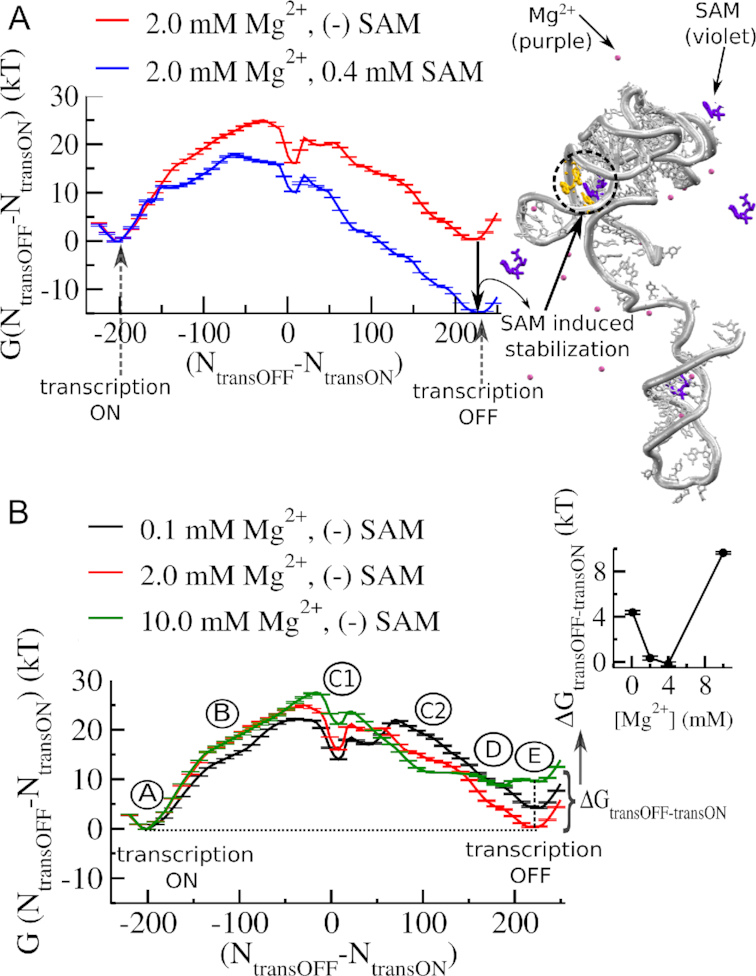

Figure 3.

Mg2+ dependence of transcription ON-OFF conformational transition of SAM-I riboswitch. (A) Free energy landscape of transcription ON–OFF transition in the absence and in the presence of metabolite, SAM (0.4 mM). The reaction coordinate is the difference in the number of native contacts that distinguish the transcription ON state (number of contacts between the aptamer and the switching strand (NtransON)) from the transcription OFF state (number of contacts between the terminator and the switching strand (NtransOFF)). Note, SAM-induced stabilization of the transcription OFF state relative to the transcription ON state in the free energy landscape. (B) Mg2+ concentration dependence of transcription ON-OFF transition of SAM-I riboswitch in the absence of SAM. Average free energy profiles at varied [Mg2+] show different stability difference between the transcription ON state and the transcription OFF state. The stability difference between the transcription ON and the transcription OFF states (ΔGtransOFF-transON) quantified as a function of [Mg2+] has a non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence, as shown in the inset. The aptamer reaches its maximum stability at around 4.0 mM Mg2+ range. Beyond 4.0 mM it starts to destabilize. Along with the stable transcription ON and OFF states (A and E, respectively), the transition involves different intermediates (B, C1, C2, D), which also have different Mg2+ sensitivity.

Navigating [Mg2+] dependent transcription ON-OFF routes for full length SAM-I riboswitch

In addition to the transcription ON (A) and transcription OFF (E) states, separated by a high barrier, the free energy profile also helps us to identify characteristic intermediates (B, C1, C2, D in Figure 4A and B) that delineate the pathway of transition. Some intermediates along the 1D-pathway are severely affected by Mg2+ concentration. For instance, close to the barrier, we find that upon addition of Mg2+, intermediate C1 becomes destabilized, while intermediate C2 becomes increasingly stabilized (Figure 4B). This difference in stability and the transcription ON-OFF contact progress profiles (Supplementary Figure S3) prompted us to resolve the pathway of transition along the transcription ON and OFF reaction-coordinates, separately. The 2D-landscapes as shown in Figure 4A and B clearly distinguish two Mg2+ concentration dependent dominant pathways, based on the formation and breaking of ON and OFF state contacts: (i) an orthogonal pathway (A→B→C1→D→E) (Figure 4A) where the switching strand is completely detached from one domain (aptamer or EP) before it swaps to another domain and (ii) a coordinated pathway (A→B→C2→D→E) (Figure 4B) where ON and OFF state contact formation or removal occurs concurrently in a cooperative/coordinated manner. This pathway involves an ON-OFF hybrid state where both the aptamer and EP remain partially folded. The representative structural intermediates along the respective pathways are shown in Figure 4C. Along the transition pathway, if we start from the transcription ON state (A), the stability of the anti-terminator helix is initially challenged by the flexible part of the aptamer that is easily formed and broken (due to P4-helix flexibility, similar to our earlier study (19)). In a first intermediate, B, shared by both pathways, partial-AT and partial-APT co-exist.

Figure 4.

Transcription ON–OFF transition routes of full-length SAM-I riboswitch. Two-dimensional free energy landscape as a function of transcription ON reaction coordinate and OFF reaction coordinate, exploring two distinct pathways at lower and higher Mg2+ concentrations. (A) At lower concentration ([Mg2+] = 0.1 mM), transition predominantly follows an orthogonal path via an entropically stable intermediate (C1). (B) At higher concentration ([Mg2+] = 10.0 mM), it preferentially follows a coordinated path via an enthalpically stabilized intermediate (C2). (C) Representative structures. The representative structure corresponding to each minimum of the energy landscape and serving as landmark on the orthogonal and coordinated pathways.

Beyond, the pathways split, and the orthogonal pathway continues to the characteristic intermediate C1 (Figure 4C). This state is entropically stabilized by a flexible region of the aptamer, formed by P1 and part of P4, which remains extended or dissociated from the aptamer in the absence of SAM and Mg2+. Folding of this flexible part depends on some key tertiary connections, such as 3′-P1-to-P3 juxtaposition and the J1/4 junction. Formation of these tertiary contacts plays a crucial role in the transition state of switching. Across the barrier, when the aptamer domain finishes folding, a tiny residual part of the anti-terminator helix still populates a shallow well, which is finally disrupted by the formation of a terminator helix. The coordinated path differs from the orthogonal path only by the central intermediate, C2, which is more compact than C1. The structure adjusts itself in such a way that the anti-terminator helix becomes additionally stabilized via early formation of the same key tertiary interactions that support the association of the aptamer domain with the EP. Some secondary structure in P1 is sacrificed to achieve the stabilization of a substantial portion of the anti-terminator helix. Among the gained interactions, the most important one is 3′-P1-to-P3 juxtaposition, which is stabilized by increasing Mg2+ concentration. This microscopic mechanism may explain the role of Mg2+ in partial anti-terminator helix stabilization (19,27).

We have also traced the transcription ON-OFF transition pathway in the presence of 0.4 mM SAM at varied Mg2+ concentration (Supplementary Figure S4). We have observed very similar phenomena as we observed in the absence of SAM. While SAM binding is responsible for stabilization of the transcription OFF state, we observed that the population gradually shifts toward the transcription ON state even in the presence of 0.4 mM SAM following the coordinated pathway by preferentially stabilizing the anti-terminator helix.

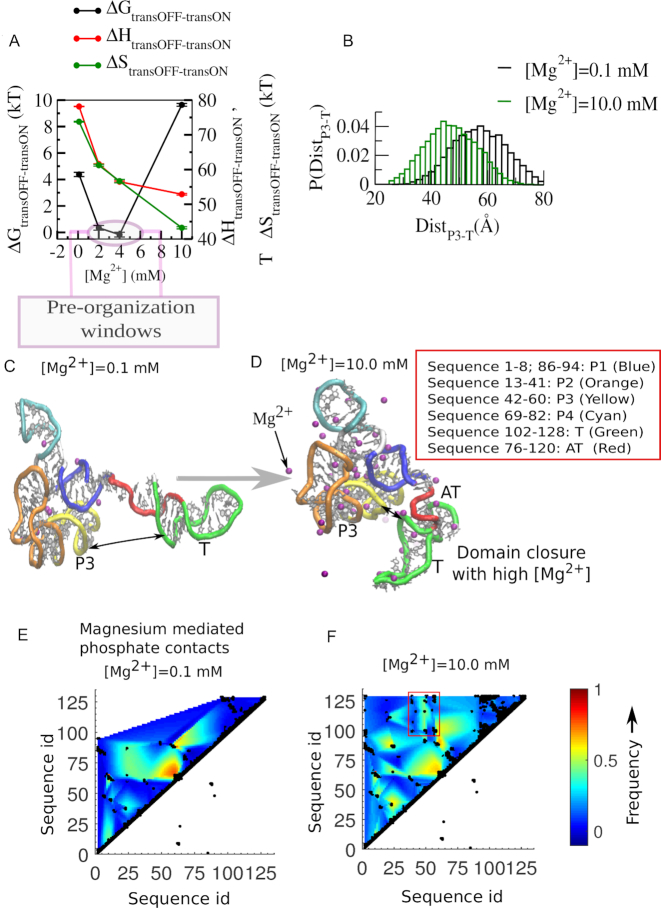

Thermodynamics and structural origin of thermodynamic destabilization of the transcription OFF-state at lower and higher Mg2+ concentration

In order to investigate the relative thermodynamic destabilization of the transcription OFF state, both at very low and at higher Mg2+ concentrations, in Figure 5A we follow the contributions from the enthalpy and the entropy to the total free energy difference (ΔGtransOFF-transON). We find that at lower Mg2+ concentrations, as we increase [Mg2+], the aptamer domain of the transcription OFF state is increasingly gaining enthalpy more than it loses entropy. Similar to our earlier study (18) here also we observed a number of multiple phosphate coordinated Mg2+ ions that help to stabilize several negatively charged phosphate groups by staying in close proximity (Supplementary Figure S5). We have calculated the prevalence of hexahydrated magnesium ions in the ion-atmosphere of full-length SAM-I riboswitch for its transcription ON and transcription OFF state and at different magnesium concentrations. Our calculations reveal that as we increase Mg2+ concentration the OFF state accommodates higher numbers of multiple phosphate coordinated Mg2+ ions as compared to that of the ON state (Supplementary Figure S5). At higher Mg2+ concentration, for the long anti-terminator helix stabilization, the transcription ON state accommodates more single phosphate coordinated Mg2+ ions as compared to the ion-atmosphere of the transcription OFF state, which has a significant amount of tertiary interactions. In addition, the implications of site-specific chelated ions for stabilization, both in the transcription ON and OFF state folds, are discussed in the Supplementary Figure S6. All the Mg2+ mediated non-native contacts facilitate the formation of the native collapsed state. We have quantified and compared the extent of collapse of the OFF state by calculating the distance closure of the anti-terminator helix and the aptamer domain (Figure 5B) varying Mg2+ concentrations, which clearly shows that the collapsed state population shifts more towards the APT-EP domain-closed-state from the APT-T OFF state as we increase Mg2+ concentration from 0.1–10 mM. We have calculated the centre of mass distance involving the residues included in the P3 helix and the same included in the T helix to measure this domain closure. Beyond 2.0–4.0 mM Mg2+, while the enthalpic stabilization reaches its saturation limit, the growing number of non-native contacts dynamically constrains the native complex, causing significant loss in entropy (Figure 5A). In order to identify the non-native interactions and to find out the molecular origin of the constraints that entropically destabilize the OFF state, we compared the structures extracted from our equilibrium simulation trajectories of the OFF state at 0.1 mM (Figure 5C) and 10.0 mM Mg2+ concentration (Figure 5D). Inspection of these two representative structures clearly reveals that at high concentration Mg2+ ions bring the aptamer domain and the EP into close proximity, via the formation of a number of new tertiary interactions that are mostly Mg2+ mediated. Our contact map analyses identify those magnesium mediated phosphate-phosphate contacts. We compared the contact maps for lower (0.1 mM Mg2+, Figure 5E) and higher magnesium (10.0 mM Mg2+, Figure 5F) concentrations and found that at higher magnesium concentration a number of new tertiary contacts are generated. Most of them connect the P3 helix of the aptamer and T-helix of the expression platform and bring the aptamer domain and the expression platform in close proximity. This closure appears to facilitate partial formation of the anti-terminator helix, in a state where a partial-P1 helix in the aptamer domain and partial terminator and partial anti-terminator structures in the EP can coexist (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Thermodynamic and structural origin of aptamer destabilization. (A) Non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence of thermodynamic quantities reflects that initial OFF state stabilization up to 4.0 mM is due to comparatively stiff enthalpic stabilization, while destabilization of the OFF state beyond 4.0 mM is due to relatively stiff entropy decrease. This entropy-led OFF-state destabilization restricts the pre-organization of the aptamer within 2.0–4.0 mM concentration window. Aptamer destabilization is caused by Mg2+ mediated domain closure. (B) The Mg2+ dependent domain closure is quantified with the distance between the aptamer and the EP (terminator (T) helix). (C) The representative OFF-state structure extracted from our simulated trajectory equilibrated at 0.1 mM. It shows the aptamer and expression-platform domain separation. (D) The representative OFF-state structure from 10.0 mM Mg2+ simulation. It shows the aptamer and the expression-platform domain (terminator (T) helix) closure within the structure where the aptamer, the anti-terminator and the terminator helices partially co-exist and restrain the dynamics attaining the maximum collapse. Magnesium mediated backbone phosphate-phosphate contact map at Mg2+ concentration (E) 0.1 mM and (F) 10.0 mM. The newly formed magnesium mediated contacts at 10.0 mM are highlighted by a rectangular box that distinguishes P3-T contacts.

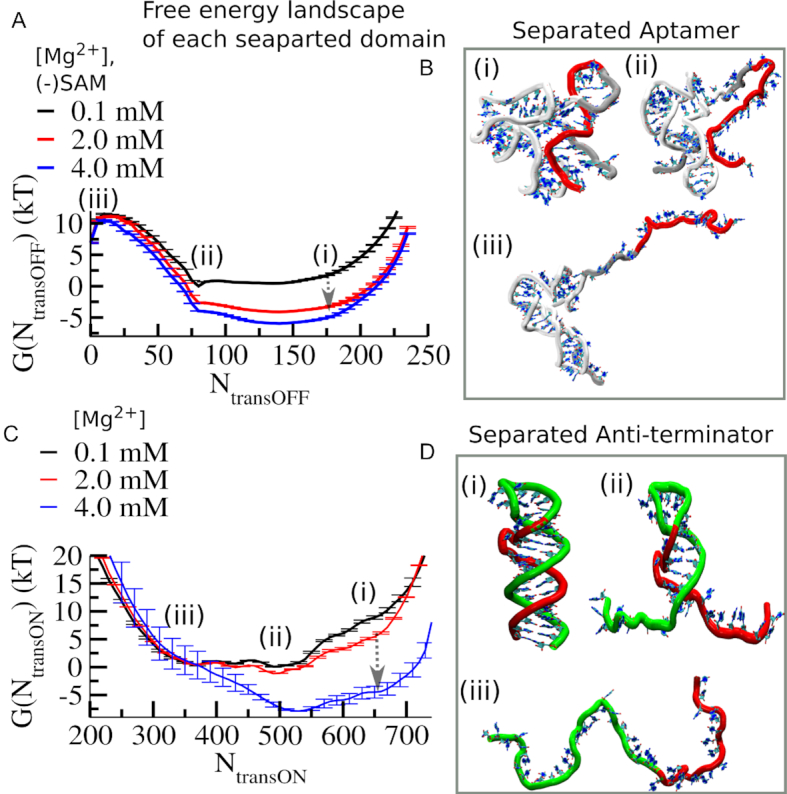

[Mg2+] sensitivity measurement for individual aptamer domain and individual anti-terminator helix separated from aptamer/anti-terminator complex

Our free energy profiles at different Mg2+ concentrations indeed capture different Mg2+ concentration dependent transition pathways and also reveal concentration dependent non-monotonic behavior of the relative stabilization of the aptamer domain with respect to the anti-terminator. As the emergence of this non-monotonic behavior for the full-length complex will always depend on the relative strengths of different contributions, it is difficult to separate the contributions from each part of the complex. At this point, one can imagine four different possibilities that might yield such a non-monotonic outcome: (i) folding of the flexible aptamer domain has a non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence, while anti-terminator is insensitive; (ii) folding of the anti-terminator has a non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence, while the aptamer domain is less sensitive; (iii) both individual units have non-monotonic [Mg2+] dependence causing a resultant non-monotonic behavior; (iv) both units have separate functional [Mg2+] regimes that combine to produce the non-monotonicity. To check and analyze all these possibilities we separately calculated the folding free energy landscape of the aptamer domain as a function of the transcription OFF-reaction coordinate (Figure 6A) and also calculated the same for the anti-terminator helix as a function of the transcription ON-reaction coordinate (Figure 6C), at varying Mg2+ concentrations. In Figure 6A, the aptamer folding landscape shows three minima which correspond to: (i) a partially closed pre-organized state, (ii) a partially open state, and (iii) an extended open state, as shown in Figure 6B. Similarly, the anti-terminator folding landscape (Figure 6C) also shows three minima: (i) a partially closed state, (ii) a partially open state and (iii) an extended open state, as shown in Figure 6D). Our previous experimental and theoretical studies on the SAM-II riboswitch revealed that a Mg2+ induced collapsed state gains increasing stability up to a critical Mg2+ concentration threshold. At this critical concentration, the stabilization attains its maximum, because subsequent additions of Mg2+ do not effectively add to the already-saturated 1st layer of Mg2+ solvation. In the current context, when we compare the two folding free energy profiles and their Mg2+ variation, we find that the critical Mg2+ concentration for the aptamer collapse is less than 2.0 mM, while it is larger than 2.0 mM for the anti-terminator ([Mg2+]1/2 values are given as Supplementary Figure S7). This comparison suggests that the collapse transition of the anti-terminator benefits most strongly from addition of Mg2+ only when the aptamer collapse transition reaches its saturation limit. From this analysis, it is clear that the Mg2+ requirements of the two individual domains are fulfilled separately. While the aptamer domain is preferentially stabilized at lower Mg2+ concentration, the anti-terminator helix needs higher Mg2+ for its stabilization.

Figure 6.

Comparative Mg2+ dependence of individual aptamer and anti-terminator domains demonstrates that the stable anti-terminator helix formation is triggered beyond 2.0 mM. (A) Average free energy profiles of folding transition of the flexible aptamer domain as a function of transcription OFF reaction coordinates at different [Mg2+] show Mg2+ induced collapse transition occurs within 0.1–2.0 mM [Mg2+] range. (B) The representative structure corresponding to each minimum of the energy landscape is designated as follows: (i) ligand-free partially closed (PC), (ii) ligand-free partially open (PO) and an (iii) open (O) state minimum. (C) Average free energy profiles of folding transition of the anti-terminator helix as a function of transcription ON reaction coordinates at different [Mg2+] show Mg2+ induced collapse transition occurs within 2.0–4.0 mM [Mg2+] range. It reflects that compared to the aptamer domain, the anti-terminator helix requires higher critical Mg2+ concentration to promote its collapse transition. (D) The representative structure corresponding to each minimum of the free energy landscape of the anti-terminator helix folding is designated as follows: (i) closed (C), (ii) partially open (PO) and an (iii) open (O) state minimum.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explore the conformational free energy landscape for the full-length SAM-I riboswitch to understand its transcription ON–OFF transition, which is essential for bacterial transcription regulation. Our EP switching assay experiment and dual basin structure-based electrostatic simulations, both in the presence and in the absence of the metabolite, SAM, find that while SAM is responsible for stabilizing the transcription OFF state, high Mg2+ concentration is responsible for ON-state stabilization. Yet, in the absence of SAM, a Mg2+ concentration-dependent non-monotonic population ratio between the transcription OFF and the transcription ON states indicates that relatively low Mg2+ concentrations also preferentially stabilize the OFF state up to 2.0–4.0 mM. The preferential stabilization of the ON state at high Mg2+ concentration correlates well with a recent smFRET experimental study on B. subtilis yitJ (30). Our dual basin simulations also reveal distinct orthogonal and coordinated transition pathways, influenced by low and high Mg2+ concentrations. Our simulation results reveal that the present coordinated pathway is essentially under the influence of Mg2+ mediated interactions that are not native. Our magnesium mediated contact map analyses pinpoint those newly formed interactions that were otherwise repulsive. These interactions instigate aptamer-EP domain closure, which causes entropic destabilization of the aptamer at higher Mg2+ concentration by constraining its free movement. The finding of these new interactions from our structure-based electrostatic simulations complements our two stranded switching assay experiment where no non-native interactions were present. In our early work, we have demonstrated experimentally that this assay adequately represents the full riboswitch within the bounds of the native functional regime of a transcriptional riboswitch (20,23). The aptamer exists without the anti-terminator sequence prior to its polymerization. It is at this point that the ‘decision’ is made for ON vs. OFF through the binding/collapse of the aptamer and the resistance this imparts to the domain for competition from the expression platform. We mimic this process with a 2-piece challenge that does not introduce anything that is non-native which gives an unambiguous signal for formation of structures that determines the stability of the aptamer. This makes the switching easier to understand. The two strand assays, however, may miss to capture the effects of different possible tertiary interactions. Although a number of new tertiary interactions (those are magnesium mediated), are fairly captured in our complementary simulation result, the underlying challenges still exist to determine if any direct nucleotide mediated new tertiary interaction evolves in the course of switching. Studying the functional impacts of all kinds of such tertiary interactions and other possible direct interactions for the full-length SAM-I riboswitch construct is necessary to fully understand the switching process. Although it is experimentally challenging, our future effort in this direction is underway. Also, our predicted aptamer-EP domain closure at high magnesium concentration can be tested in the future by smFRET or by SAXS experiments on the full-length RNA construct.

While numerous earlier studies on different riboswitches find Mg2+ induced collapse state stabilization of aptamers, we believe that this is the first case where structural evidence shows how Mg2+ can destabilize a compact aptamer fold. Earlier smFRET, SHAPE, SAXS, and structure-based simulation studies have already evaluated the impact of Mg2+ ions on the aptamer domain of SAM-I riboswitch (19,22,24,25,27,29,31). All these studies consistently found the role of Mg2+ ions in stabilizing a sparsely populated, compact, pre-organized conformation that resembles the ligand-bound state, and identified the key interactions that are associated with non-local P1 helix stabilization. This type of Mg2+ induced aptamer pre-organization could facilitate termination of transcription in response to ligand binding by speeding up folding of the aptamer domain. To form a binding competent pre-organized conformation, stabilization of the P1 helix and its juxtaposition with the P3 helix is of high importance as they support stable ligand binding (26). For the full-length SAM-I riboswitch, we observe that it can pre-organize at most up to the 4.0 mM Mg2+ range. While this RNA is electrostatically unstable at very low Mg2+ concentration (<0.4 mM), at very high Mg2+ concentration this multi-domain RNA becomes entropically destabilized. This gives rise to a narrow Mg2+ concentration window for SAM-I pre-organization which offers the only opportunity to accelerate the transcription OFF rate. Our study suggests that it is important for maintaining balance in bacterial gene regulation at physiological Mg2+ concentrations, which fall into this intermediate regime. This intermediate physiological concentration regime appears to preserve a subtle balance between the transcription OFF and transcription ON states where the population of the pre-organized aptamer domain can accelerate stable ligand binding. Around this intermediate range the aptamer domain possibly reaches its maximum pre-organization limit. This prediction, however, warrants further experimental verification to assess the benefit of pre-organization for SAM binding to the full-length riboswitch in this intermediate Mg2+ regime. This behavior appears to provide ‘a window of opportunity’ for targeting transcription termination in order to maintain cell homeostasis in terms of bacterial gene regulation. There will, however, be other complex interactions in the cellular environment. Yet, as electrostatic interactions are more impactful, this equilibrium shift might play an important role despite other complexities in controlling transcription ON-OFF switching.

We have also investigated the effect of Mg2+ at different concentrations on the conformational landscape of the two competing units of this riboswitch, the aptamer domain and the anti-terminator domain, independently, and also for the whole complex, using both experimental and computational approaches. Our SHAPE probing experiment and single-basin structure-based model simulation consistently find that the aptamer domain of the riboswitch undergoes a collapse transition with a transition mid-point ([Mg2+]1/2) around 0.4 mM, and that the aptamer domain collapse reaches its saturation limit around 2.0–4.0 mM Mg2+. On the other hand, the folding free energy landscape of the separated anti-terminator helix and its variation with [Mg2+] suggest that the collapse transition for this part of the riboswitch becomes active beyond 2.0 mM. This explains why beyond the 2.0–4.0 mM Mg2+ range, the equilibrium shifts towards the anti-terminator population. We observed this phenomenon both in the absence and presence of the metabolite. Even in the presence of metabolite, addition of Mg2+ (at high concentration) shifts the equilibrium towards the AT/ON state (Supplementary Figure S4). Hence, magnesium is as competent as the metabolite in controlling transcription of SAM-I downstream genes.

In any situation, SAM-bound or free, high Mg2+ concentrations shift the transcription ON–OFF equilibrium towards the ON-state. While SAM-responsive riboswitches are believed to cause termination of transcription upon metabolite binding (26,56), the present study suggests that the outcome of metabolite-responsive gene regulation may differ at certain Mg2+ concentrations.

The parallel code used to simulate the potential is available for download at the following link: http://smog.rice.edu/SBMextension.html.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge technical support and resources from the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics. SR thanks Professor Peter G. Wolynes, Dr Ryan L. Hayes, Dr Jeffrey K. Noel, Dr Xingcheng Lin, Dr Biman Jana and Dr Xiaoqin Huang for many helpful discussions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institute of Health (NIH) [RO1-GM110310 to J.N.O., RO1-GM110310 to K.Y.S.]; Center for Theoretical Biological Physics. Work at the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics is also supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) [PHY-1427654 and NSF-CHE-1614101]; Welch Foundation [C-1792]. Funding for open access charge: NIH [RO1-GM110310].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Breaker R.R. Prospects for riboswitch discovery and analysis. Mol. Cell. 2011; 43:867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grundy F.J., Henkin T.M.. The S box regulon: a new global transcription termination control system for methionine and cysteine biosynthesis genes in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1998; 30:737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Montange R.K., Batey R.T.. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008; 37:117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nahvi A., Sudarsan N., Ebert M.S., Zou X., Brown K.L., Breaker R.R.. Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem. Biol. 2002; 9:1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Batey R.T. Structures of regulatory elements in mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006; 16:299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Batey R.T. Recognition of S-adenosylmethionine by riboswitches. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011; 2:299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cantoni G.L. Biological methylation: selected aspects. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1975; 44:435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fontecave M., Atta M., Mulliez E.. S-adenosylmethionine: nothing goes to waste. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004; 29:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erion T.V., Strobel S.A.. Identification of a tertiary interaction important for cooperative ligand binding by the glycine riboswitch. RNA. 2011; 17:74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haller A., Altman R.B., Souliere M.F., Blanchard S.C., Micura R.. Folding and ligand recognition of the TPP riboswitch aptamer at single-molecule resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:4188–4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDaniel B.A., Grundy F.J., Henkin T.M.. A tertiary structural element in S box leader RNAs is required for S-adenosylmethionine-directed transcription termination. Mol. Microbiol. 2005; 57:1008–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bisaria N., Greenfeld M., Limouse C., Pavlichin D.S., Mabuchi H., Herschlag D.. Kinetic and thermodynamic framework for P4-P6 RNA reveals tertiary motif modularity and modulation of the folding preferred pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016; 113:E4956–E4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lipfert J., Das R., Chu V.B., Kudaravalli M., Boyd N., Herschlag D., Doniach S.. Structural transitions and thermodynamics of a glycine-dependent riboswitch from Vibrio cholerae. J. Mol. Biol. 2007; 365:1393–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Misra V.K., Draper D.E.. On the role of magnesium ions in RNA stability. Biopolymers. 1998; 48:113–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yamauchi T., Miyoshi D., Kubodera T., Nishimura A., Nakai S., Sugimoto N.. Roles of Mg2+ in TPP-dependent riboswitch. FEBS Lett. 2005; 579:2583–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang W., Kim J., Jha S., Aboul-Ela F.. A mechanism for S-adenosyl methionine assisted formation of a riboswitch conformation: a small molecule with a strong arm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:6528–6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vogel U., Jensen K.F.. The RNA chain elongation rate in Escherichia-coli depends on the growth-rate. J. Bacteriol. 1994; 176:2807–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roy S., Lammert H., Hayes R.L., Chen B., LeBlanc R., Dayie T.K., Onuchic J.N., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. A magnesium-induced triplex pre-organizes the SAM-II riboswitch. Plos Comput. Biol. 2017; 13:e1005406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roy S., Onuchic J.N., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. Cooperation between magnesium and metabolite controls collapse of the SAM-I riboswitch. Biophys. J. 2017; 113:348–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hennelly S.P., Novikova I.V., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. The expression platform and the aptamer: cooperativity between Mg2+ and ligand in the SAM-I riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:1922–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayes R.L., Noel J.K., Mandic A., Whitford P.C., Sanbonmatsu K.Y., Mohanty U., Onuchic J.N.. Generalized manning condensation model captures the RNA ion atmosphere. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015; 114:258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayes R.L., Noel J.K., Mohanty U., Whitford P.C., Hennelly S.P., Onuchic J.N., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. Magnesium fluctuations modulate RNA dynamics in the SAM-I riboswitch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012; 134:12043–12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hennelly S.P., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. Tertiary contacts control switching of the SAM-I riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:2416–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stoddard C.D., Montange R.K., Hennelly S.P., Rambo R.P., Sanbonmatsu K.Y., Batey R.T.. Free state conformational sampling of the SAM-I riboswitch aptamer domain. Structure. 2010; 18:787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whitford P.C., Schug A., Saunders J., Hennelly S.P., Onuchic J.N., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. Nonlocal helix formation is key to understanding S-adenosylmethionine-1 riboswitch function. Biophys. J. 2009; 96:L7–L9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Montange R.K., Batey R.T.. Structure of the S-adenosylmethionine riboswitch regulatory mRNA element. Nature. 2006; 441:1172–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu C.R., Ding F., Chowdhury A., Pradhan V., Tomsic J., Holmes W.M., Henkin T.M., Ke A.L.. SAM recognition and conformational switching mechanism in the bacillus subtilis yitJ S Box/SAM-I riboswitch. J. Mol. Biol. 2010; 404:803–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dussault A.M., Dube A., Jacques F., Grondin J.P., Lafontaine D.A.. Ligand recognition and helical stacking formation are intimately linked in the SAM-I riboswitch regulatory mechanism. RNA. 2017; 23:1539–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eschbach S.H., St-Pierre P., Penedo J.C., Lafontaine D.A.. Folding of the SAM-I riboswitch: a tale with a twist. RNA biology. 2012; 9:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manz C., Kobitski A.Y., Samanta A., Keller B.G., Jaschke A., Nienhaus G.U.. Single-molecule FRET reveals the energy landscape of the full-length SAM-I riboswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017; 13:1172–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heppell B., Blouin S., Dussault A.M., Mulhbacher J., Ennifar E., Penedo J.C., Lafontaine D.A.. Molecular insights into the ligand-controlled organization of the SAM-I riboswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011; 7:384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manz C., Kobitski A. Y., Samanta A., Jäschke A., Nienhaus G.U.. The multi-state energy landscape of the SAM-I riboswitch: a single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer spectroscopy study. J. Chem. Phys. 2018; 148:123324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lutz B., Faber M., Verma A., Klumpp S., Schug A.. Differences between cotranscriptional and free riboswitch folding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:2687–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flores S.C., Sherman M.A., Bruns C.M., Eastman P., Altman R.B.. Fast flexible modeling of RNA structure using internal coordinates. IEEE ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. 2011; 8:1247–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stoddard C.D., Montange R.K., Hennelly S.P., Rambo R.P., Sanbonmatsu K.Y., Batey R.T.. Free state conformational sampling of the SAM-I riboswitch aptamer domain. Structure. 2010; 18:787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen B., LeBlanc R., Dayie T.K.. SAM-II riboswitch samples at least two conformations in solution in the absence of ligand: Implications for recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016; 55:2724–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen B., Zuo X., Wang Y.X., Dayie T.K.. Multiple conformations of SAM-II riboswitch detected with SAXS and NMR spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 40:3117–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haller A., Rieder U., Aigner M., Blanchard S.C., Micura R.. Conformational capture of the SAM-II riboswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011; 7:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ontiveros-Palacios N., Smith A.M., Grund F.J., Soberon M., Henkin T.M., Miranda-Rios J.. Molecular basis of gene regulation by the THI-box riboswitch. Mol. Microbiol. 2008; 67:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suddala K.C., Wang J.R., Hou Q., Water N.G.. Mg2+ shifts ligand-mediated folding of a riboswitch from Induced-Fit to conformational selection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015; 137:14075–14083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Onuchic J.N., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P.G.. Theory of protein folding: the energy landscape perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997; 48:545–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wolynes P.G. Evolution, energy landscapes and the paradoxes of protein folding. Biochimie. 2015; 119:218–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferrenberg A.M., Swendsen R.H.. Optimized Monte Carlo data analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989; 63:1195–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torrie G.M., Valleau J.P.. Monte-Carlo Free-Energy estimates using Non-Boltzmann Sampling - Application to subcritical Lennard-Jones fluid. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1974; 28:578–581. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andrews B.T., Gosavi S., Finke J.M., Onuchic J.N., Jennings P.A.. The dual-basin landscape in GFP folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:12283–12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jana B., Morcos F., Onuchic J.N.. From structure to function: the convergence of structure based models and co-evolutionary information. PCCP. 2014; 16:6496–6507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lammert H., Schug A., Onuchic J.N.. Robustness and generalization of structure-based models for protein folding and function. Proteins. 2009; 77:881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kirmizialtin S., Hennelly S.P., Schug A., Onuchic J.N., Sanbonmatsu K.Y.. Integrating molecular dynamics simulations with chemical probing experiments using SHAPE-FIT. Methods Enzymol. 2015; 553:215–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Deigan K.E., Li T.W., Mathews D.H., Weeks K.M.. Accurate SHAPE-directed RNA structure determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wilkinson K.A., Merino E.J., Weeks K.M.. Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nat. Protoc. 2006; 1:1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Montange R.K., Mondragon E., van Tyne D., Garst A.D., Ceres P., Batey R.T.. Discrimination between closely related cellular metabolites by the SAM-I riboswitch. J. Mol. Biol. 2010; 396:761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Noel J.K., Whitford P.C., Onuchic J.N.. The shadow map: a general contact definition for capturing the dynamics of biomolecular folding and function. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012; 116:8692–8702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aboul-ela F., Huang W., Abd Elrahman M., Boyapati V., Li P.. Linking aptamer-ligand binding and expression platform folding in riboswitches: prospects for mechanistic modeling and design. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2015; 6:631–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boyapati V.K., Huang W., Spedale J., Aboul-ela F.. Basis for ligand discrimination between ON and OFF state riboswitch conformations: the case of the SAM-I riboswitch. RNA. 2012; 18:1230–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Song B., Leff L.G.. Influence of magnesium ions on biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Microbiol. Res. 2006; 161:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Price I.R., Grigg J.C., Ke A.. Common themes and differences in SAM recognition among SAM riboswitches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014; 1839:931–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.