Abstract

Background

Malnutrition is one of the most important reasons for child mortality in developing countries, especially during the first 5 years of life. We set out to systematically review evaluations of interventions that use mobile phone applications to overcome malnutrition among preschoolers.

Methods

The review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. To be eligible, the study had to have evaluated mobile phone interventions to increase nutrition knowledge or enhance behavior related to nutrition in order to cope with malnutrition (under nutrition or overweight) in preschoolers. Articles addressing other research topics, older children or adults, review papers, theoretical and conceptual articles, editorials, and letters were excluded. The PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases covering both medical and technical literature were searched for studies addressing preschoolers’ malnutrition using mobile technology.

Results

Seven articles were identified that fulfilled the review criteria. The studies reported in the main positive signals concerning the acceptance of mobile phone based nutritional interventions addressing preschoolers. Important infrastructural and technical limitations to implement mHealth in low and middle income countries (LMICs) were also communicated, ranging from low network capacity and low access to mobile phones to specific technical barriers. Only one study was identified evaluating primary anthropometric outcomes.

Conclusions

The review findings indicated a need for more controlled evaluations using anthropometric primary endpoints and put relevance to the suggestion that cooperation between government organizations, academia, and industry is necessary to provide sufficient infrastructure support for mHealth use against malnutrition in LMICs.

Keywords: Mobile phone, Malnutrition, Intervention, Preschoolers

Background

Malnutrition is one of the most important reasons for child mortality in developing countries, especially during the first 5 years of life. Malnutrition is a condition of deficiency or excess of nutrients which leads to sensible adverse effects on body composition and functionality [1–3]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) reports, 52 million children under 5 years of age are wasted, 17 million are severely wasted and 155 million are stunted, while 41 million are overweight or obese [4]. It is well known that early deficiencies in the intake of nutrients not only have a negative influence on child health and development, but it also reduces work efficiency and leads to poor reproductive outcomes in adult life through impaired immune response and susceptibility to infections, digestive problems, predisposing for vicious cycles of recurring sickness, faltering growth and diminished learning ability [5–8]. On the other hand, children who are overweight during their pre-school years tend to remain overweight throughout childhood and adolescence, which increases the risk suffering of cardiovascular disease, several forms of cancer, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses [9, 10]. The causal chain leading to malnutrition in early childhood is complex with a variety of direct and underlying contributors including household access to food and the distribution of this food within the household, inadequate maternal and child care practices, and poor access to health-care services [11, 12]. Knowledge of these factors is an essential prerequisite for determining intervention programs addressing preschoolers malnutrition [13]. A recent review of factors influencing information and communication technology (ICT) introduction in health services showed that one main type of technology that has been adopted by broad categories of healthcare users and patients is mobile and cell phone technologies and these kind of studies are going to be published broadly [14, 15]. At present, mobile technologies allow development of mHealth (mobile health) interventions that have promised to be a useful and low-cost way to disseminate information about proper nutrition and a critical source of motivation for behavioral change [16, 17]. A systematic review has investigated the effect sizes of pediatric obesity intervention studies using of mobile technology within the elementary school students. Based on four included studies, analyses showed that the mobile interventions positively affected dropout rates, but had no influence on weight control, exercise, and sugar-sweetened beverage intake [18]. Another systematic review of the effectiveness of using smartphones on child and adolescent overweight reported a significant effect on Body Mass Index (BMI) z-scores [19]. Furthermore, a recent review identified a number of weight management applications developed for children > 12 years. Most were free or inexpensive to download and accordingly attractive for parents of obese children. The investigations found the overall quality of the application contents generally being very poor and not based on credible dietary guideline [20]. To our knowledge, no reviews have been conducted on dietary interventions based on mobile phone applications addressing preschoolers’ malnutrition.

We set out to systematically review evaluations of interventions that use mobile phone applications to overcome malnutrition among preschoolers.

Methods

The review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement [21].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible in this review, the study had to have evaluated mobile phone interventions to increase nutrition knowledge or enhance behavior related to nutrition in order to cope with malnutrition (under nutrition or overweight) in preschoolers. Articles addressing other research topics, older children or adults, review papers, theoretical and conceptual articles, editorials, and letters were excluded.

Search strategy

A literature search procedure was carried out in March 2018 based upon bibliographic searches in the PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases covering both medical and technical literature. English-only articles without any date restriction were identified using the following MeSH terms: (“Child Nutrition Disorders” OR Malnutrition OR “child Weight” OR “Pediatric Thinness” OR “Pediatric Obesity” OR “Pediatric Feeding Disorders”) AND (“Mobile Applications” OR smartphone OR “cell phones” OR “mobile phones” OR mobile OR “portable software app”). Additionally the following key journals in the health informatics sciences (Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Journal of Medical Internet Research, and Telemedicine and e-Health) were manually searched to prevent the likelihood of omitting relevant articles. The author, title, journal, year of publication and abstract for each article were compiled into a single EXCEL file. By removing duplicates only 1775 articles remained.

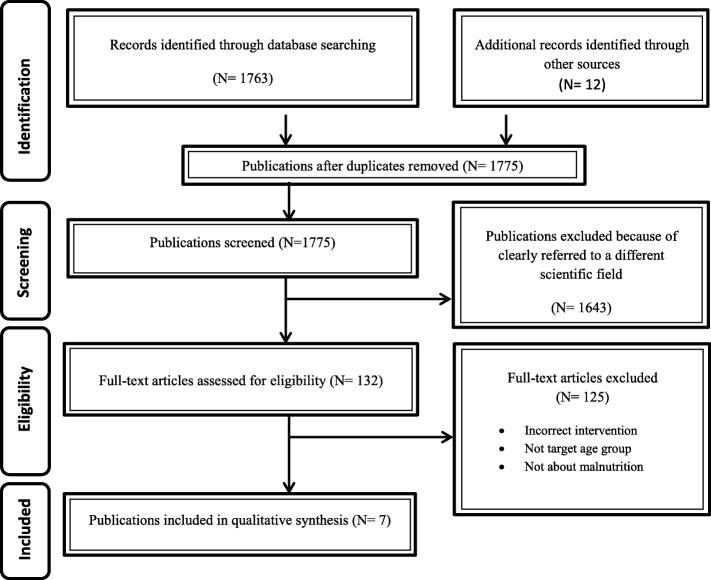

Our initial search identified 296 titles from PubMed, 667 from Web of Science and 800 from Scopus; of these, only seven articles met all search criteria (Fig. 1). The references of the included studies were retained in a list to further reduce the likelihood of missing relevant articles. Finally, data were extracted and evaluated (design, outcomes, sample size, duration of intervention and advantages of and barriers to using mobile devices) by three independent researchers. The results were organized into four main emerging themes for clarity of presentation.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

Results

The seven articles fulfilling the review criteria reported studies with designs ranging from case studies to RCTs. All articles were published between 2015 and 2017. Four of the reported interventions were conducted using a mobile phone application, and two interventions used the combination of SMS on mobile phone and an ICT tool or face-to-face visit interventions. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the included publications.

Table 1.

Selected publications

| Authors & (Publication Date) | Study design | Study objective | Intervention | Intervention setting & Population | Main study results & endpoints | Weaknesses and limitations | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hull et al. [22]. 2017 Aug |

Prototype, Usability testing | To test the application prototype with target users, focusing on usage, usability, and perceived barriers and benefits of the app. | A prototype designed application that includes some shopping tools such as a barcode scanner and calculator tools for the cash value voucher for purchasing fruits and vegetables, and nutrition education focused on healthy snacks and beverages | (African Americans and Hispanics in the United States) (80 mothers of children ages 2 to 4.5 years) (3 months duration) |

The app prototype successfully demonstrated the feasibility of using it. Although, Some technical barriers reported by users. Also a few of them indicated more problems with the app not being easy enough to use, lack of interest in the content, forgetting to use it, or not noticing alerts. | 1- Compatibility issues with different Android platforms 2- Limited support of vendors 3- technical barriers and delay in updating the database |

1- High willingness to shopping tools including a barcode scanner and calculator tools for the cash value voucher for purchasing fruits and vegetables 2- improving food purchasing behaviors, parent feeding strategies |

| Nyström et al. [23]. 2017 April |

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | To assess the effectiveness of a mHealth obesity prevention program on body fat, dietary habits, and physical activity in healthy Swedish children aged 4.5 y. | The application consisted of an extensive program of information and support grounded in social cognitive theory and behavior change techniques and was centered around existing guidelines for healthy eating and physical activity | (Ostergotland, Sweden) (315 preschool-aged children were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group.) (Parents in the intervention group received a 6-mo mHealth program.) |

No statistically significant intervention effect was observed for Fat Mass Index (FMI) between the intervention and control group. However, the intervention group increased their mean composite score from baseline to follow-up, whereas the control group did not. | 1- Children of normal weight were included, which may have diluted the effect of the intervention on FMI. 2- the intervention was provided only in Swedish |

1- compatible with both iOS and Android operating systems 2- intervention was grounded in social cognitive theory 3- careful calculation of statistical power 4- validated measures for dietary intake |

| Shah et al. [24]. 2016 Dec |

Pilot study with quantitative approach | To test the feasibility and acceptability of such ICT based approach. | Mobile based videos for training of all the (health) field workers to increase the nutritional and health status of children between 0 and 6 yrs. | Jogmodi beat in India was selected for the pilot. Jogmodi beat had 25 AWWs (Anganwadi Workers). (4 weeks duration) |

The feedbacks indicated that old unhealthy practices are still followed in the village in the name of religion and old traditions. According to reports the major barrier was availability of communication network problem in their village. | 1- low availability of communication network 2- The role of the supervisor was not clear that needs to be planned in the way forward |

1- Using videos as an effective media 2- Intervention developed in various local languages which cover all topics relating to malnutrition and its care. 3- Giving recharge for calling for the oral exam |

| Weerasinghe et al. [25]. May 2016 |

Formative study with qualitative approach | To understand the nature of mobile phone use and perceptions of m-health for infant and young child feeding counseling among the mothers, their family members, and service providers | using m-health counseling for infant and young child feeding | (Sri Lankan Tea Estates) (27 focus group discussions with mothers, fathers and grandmothers of the children under the age of 5) (15 in-depth interviews with health care team) |

Mothers’ perception were positive about receiving health related massages and reminders on Child Feeding through phones. On the other hand, Health workers were willing to mobile intervention as a supplementary method to face-to-face interaction. According to results m-health platform could be a promising initiative to improve the nutritional status of children. |

1- Low availability of mobile phones 2- Distribution of signal strength is not adequate in some area |

1- Mothers’ tendency to receive mobile-technology based counseling. 2- health workers were willing to use mobile phones as a complementary to strengthen communications |

| Militello et al. [26]. (October 1, 2015) |

Case study (mostly qualitative approach) | 1. To assess correlations among the study variables (healthy lifestyle beliefs, perceived difficulty, and healthy lifestyle behaviors) in parents of overweight /obese preschool children. 2. If the parent’s level of cognitive beliefs and perceived difficulty of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors correlated with text messaging cognitive behavioral support. |

The intervention relies on Cognitive Behavioral Skills Building (CBSB) to include nutrition and physical activity knowledge, problem solving, goal setting, effective communication, positive self-talk, and positive thinking. The program was delivered through a combination of clinic visits, homework/ reinforcement, reminders (manual or audio option), and text message triggers. | (Columbus, USA) Sample of 15 parent-preschooler dyads (13 parents and 15 overweight/ obesity preschoolers aged 3 through 5 years) |

This finding indicated that the parents’ level of cognitive beliefs and perceived difficulty of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors correlated with the text messaging cognitive behavioral support. As parental healthy lifestyle beliefs increased and perceived difficulty lessened, their response rate and subsequent feedback lessened to the static text messaging support. |

1- using text messaging (SMS) that considered to be not effective as a mobile application because of its constraints 2- It is unknown whether the SMS were perceived by participants as motivators, facilitators, or reminders to act. |

1- Utilizing Beck’s Cognitive Theory for intervention content 2- Utilizing Fogg’s Behavior Model for the implementation. |

| Denney-Wilson et al. [27]. BMJ open. 2015 Nov 1 |

Non-randomized quasi experimental | To assess: 1. The feasibility of PHC practitioners referring parents to and incorporating an m-health intervention and reinforcing key messages as part of routine baby health checks; 2. The effectiveness of an m-health intervention in terms of its reach, use, acceptability, cost and impact on key infant nutrition and feeding outcomes. |

The program is a smartphone app, website and online forum providing parents living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas with a ‘one-stop shop’ for evidence based advice and tips, consistent with national guidelines on infant feeding in the first 9 months of life. | (200 parent/child dyads to the intervention arm) (infant age less than 3 months, 6 months and 9 months) |

Child Health nurses’ staff acknowledged that the content was consistent with guidelines and agreed to participate in the study and refer parents to the app. | 1- Because of study budget and timeframe limitations, intervention term is restricted to 9 months of age that is not sufficient to get desirable effects | 1- Developing the intervention content tailored to age of child. 2- Using sound theoretical framework. 3- the content consistency with guidelines 4- Utilizing recruitment strategies to Motivate participants into the intervention |

| Charles et al. [28]. 2016 IEEE/ACIS 15th International Conference |

Case study with qualitative approach | The study uses both theoretical and practical approach to define the factors that fuel malnutrition and its other cause, how Information and Communication Technology tools can help to grasp the fact. Therefore, the developed tool will mainly have an SMS platform. | The Online Nutrition Surveillance System gives a possible push and pull system where information is gathered and retrieved upon request by either SMS or the web-based portal and visiting the nearest tele-center as a means of both advocacy and information sharing to minimize the information gap consequently improve household knowledge . | 50 respondents were selected from the major sub-counties of western Uganda to facilitate the research process about a population of concern. | Regarding the study, SMS platform, Discussion forum, Mailing list and more components of the web-based portal were suggested as effective ways to expand awareness and knowledge sharing about malnutrition. | 1- Limited capabilities due to weakness in available ICT infrastructure. 2- Enormous challenges like lack of a database and information system, inadequate standardized data collection |

1- focus on finding the most appropriate ways of information distribution of malnutrition best practices 2- Utilizing the combination advantages of SMS platform, Discussion forum and Mailing list. 3- Using SMS on mobile phone as an alternative for individuals that can’t afford a smart phone to access a web-portal |

Participants’ perceptions of mobile phone use for nutritional counseling

The study participants that provided their perceptions of issues and attitudes related to preschoolers feeding and use of mobile phones were mainly mothers and healthcare workers.

Mothers’ perceptions of nutritional counseling by mobile phone

A study performed in a poor region of Sri Lanka reported that only a small proportion of mothers to preschoolers owned personal mobile phones or had access to their husband’s mobile phone. Signal strength was different in various parts of the region and in some areas it was very low. According to the women’s perception, they were assured that nobody would disagree if they used a mobile phone for purposes such as contacting the husband and Public Health Midwives (PHM) or getting health information. They stated that they used stationary phones, and had not experienced any need to acquire a mobile phone. The mothers were agree about receiving health-related massages and reminders on Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) by phone and they were willing to learn the new technology for the benefit of their children [22]. Also from another study, the mothers’ interventional behaviours were reported to be affected by their opportunities, capabilities, and motivation. They tended to receive positive, affirming and personalized messages [23]. This pattern was also reflected in the Mobile-based Intervention Intended to Stop Obesity in Preschoolers (MINISTOP) RCT, where the mothers’ participation appetency was slightly lower in the youngest age group and also low-income families [24].

Health workers’ perceptions of nutritional counseling by mobile phone use

Health workers in a poor region of developing country (Sri Lanka) have been reported to perceive that mobile messaging, voice or text, mainly should be a supplementary method to face-to-face interaction. They were not sure about their capability of using the technology for complex tasks, such as entering data, if required in a mHealth initiative [22]. In comparison, in the work-up for the Growing healthy study, Child health nurses were found to be willing to learn from feedback provided by the application. They also acknowledged that the content was consistent with concurrent guidelines and agreed to refer parents to the application [23].

Technical and usability feedbacks

Technical issues were reported by mothers to make a specific feature or an entire mobile phone barcode scanner application impossible to use. These issues were minor phone damage, installation failure, and features with incorrect operation (bugs). A few mothers indicated that dissatisfaction with the applications not being user friendly also lessened their interest in the educational content and alerts. However, the major problem with the application was identified as barcode scanner incompatibility with Android phones. Some errors and updating delay were also reported in database of WIC-approved (Women, Infants, and Children) items identified by the grocery store chains. Moreover, the Yummy Snack Gallery (designed to provide parents practical skills to improve healthy dietary for children) gained high scores on the measures such as ease of use, supportiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction [25]. However, the collected feedback results showed that several participants could not continue the program because of low communication network availability in their region. The other barriers to continued participation included, for example, video deleted by error and inaccessibility to videos in spouse’s mobile phone working out of town [26].

Factors affecting m-health intervention usage and adoption

A case study aimed to investigate associations between mothers’ healthy lifestyle beliefs, perceived difficulty, and healthy lifestyle behaviors with regards to their overweight preschoolers. The results showed reverse relationship between healthy lifestyle beliefs and perceived difficulty to apply those behaviors. The study continually assessed the correlation between lifestyle variables and cognitive behavioral support through text messaging. Stronger beliefs correlated with a lower tendency to respond to the static SMS and automated feedback. Similarly, less perceived difficulty was related to lower reaction rate to the text messaging [27].

ICT systems acceptance is known to be associated with challenges concerning technological and attitude aspects [15]. In a large-scale requirements analysis addressing information systems providing decision support with regards to malnutrition issues, 50 respondents were selected from the major sub-countries of western Uganda. The study revealed significant weaknesses in available ICT infrastructure and major challenges associated with lack of a database technology and standardized means for data collection [28].

Efficacy (impact) of m-health intervention on child weight

Only one study (MINISTOP) reported efficacy outcomes from a controlled evaluation. The primary outcome was Fat Mass Index (FMI). While the secondary outcome was a combination of scores such as consumed fruits, vegetables, candy, and sweetened beverages as well as physical activity time span. However, the primary outcome between the intervention and control groups had no change but the intervention group could improve the composite score ultimately. The children with a higher FMI had been affected by the intervention more than others because these children need it more [24].

Discussion

The review revealed from evaluations of mobile phone based interventions to improve nutritional conditions among preschoolers that although mobile communication is now part of the everyday life in most global settings, the use of mHealth applications to provide health information and care is still challenging. It has been pointed out that the essential considerations for successful implementation of mHealth innovations include consideration of local infrastructure and the importance of building supportive environments [29]. A key finding in our review is that studies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), reflecting impact from local conditions, reported infrastructural and technical limitations to implement mHealth ranging from low network capacity, inadequate distribution of signal strength, and low access to mobile phones to specific technical barriers, such as delay in database updating. These observations add relevance to the suggestion that cooperation between government organizations, academia, and industry is necessary to provide sufficient infrastructure support for mHealth use in LMICs [30].

Another main result of our review is that only one article [24], reporting a 6-month intervention involving healthy Swedish children aged 4.5 years via a smartphone application that provided educational information, addressed primary outcomes. The authors found no difference between the intervention and control group concerning FMI measurements. This can be resulted from several factors; one of them considered to be inclusion of all kids regardless of baseline FMI, i.e. also children with normal weight and body fat. The mHealth interventions period was limited and these interventions did not fundamentally change the anthropometric measurements. However lifestyle were promoted changes that may ultimately result in healthier body composition. For providing mHealth interventions that impact anthropometric outcomes among children and adolescents, it is suggested that the duration of interventions measuring BMI levels extend longer than 20 weeks [31]. Moreover, it has been argued that a high quality economic evaluations of public health intervention is needed which can estimate costs and effects which looks more responsive to the needs of the decision makers using them [32–34]. Contrary to our expectations, none of the included studies assessed the economics aspect of the investigated health application in a clear way, but the authors of one article indicated an economic evaluation of the program will be performed in the future [23].

The main mechanism by which mobile phone technologies support at risk of nutrition-related disorders is by raising patient involvement and increasing self-management abilities [35, 36]. The most frequent barrier towards combating pediatric nutritional problems that was expressed by study practitioners was lack of parent involvement [37]. But in contrast to adults who can accept the responsibility of monitoring and adjusting their own treatment, the liability of nutritional interventions in preschoolers is by their parents [38, 39]. Therefore, guidance in parenting methods and behavioral management procedures should be considered as key areas in mHealth interventions aimed at preventing or treating children’s nutrition-related problems [37, 40].

Although the insights gained from our study provided positive signals concerning the acceptance of mobile phone based nutritional interventions addressing preschoolers, obstacles such as lack of time, cost, support staff, right referral resources, concern about parental responses, and lack of knowledge, skills and training in the area were reported. For instance, sever variations in compatibility between manufacturers affecting the use of a barcode scanner, have been reported. As the solution, the authors suggested use of the iPhone Operating System (iOS) platform, known seldom to be associated with compatibility issues. It can thus be recommended that logistic support, staff time, consumer preference, and cost factors are investigated before starting mHealth programs. Thoroughly understanding stakeholders’ utilization of mobile phones can be helpful in recognizing key indicators identified with feasibility and ideal usage of such innovation to avert or potentially diminish the rate of wellbeing related issues [41]. Several studies have indicated generally positive attitudes toward telecommunication and mHealth strategies [42, 43]. A qualitative study among health care providers that surveyed attitudes towards mHealth reported that potential advantages of incorporating mHealth technology also include the lessening of literacy obstructions, writing mistakes and redundancy, and an expanded feeling of privacy for the clients, even though significant concerns expressed by providers included increased network connectivity needs and liability for the devices [44].

In our review only one of the studies has used an intervention that is relied on CBSB. mHealth tools have the potential to become involved with users in real time and in highly tailored ways to encourage healthy habits, based on collection of personal data, gathered feedbacks from the user and activity levels [45, 46]. There are some concerns about incorporating evidence-based content and theory-based strategies alongside promoting behavioral changes. Several investigators have suggested for using of models to inform the design of Behavioral Intervention Technologies (BITs) as a key strategy [47–51]. For example Fogg in his model introduced behavior as a product of three factors: motivation, ability, and triggers which must occur at the same moment, else the behavior will not happen [49]. But in another study by David C Mohr et al. these models have been said offer little information on how to design and implement BITs. So an expansive hybrid framework that consolidates behavioral standards with technological aspects has been suggested by them. This framework can be helpful to connect the fields of behavioral science and technology [52].

Limitations

Limitations in this systematic review included a risk of review bias. Important findings may have been overlooked from excluded studies not published in English or that involved mobile application interventions for children and adolescents out of our age criteria. The small number of available studies, especially randomized controlled trials, limits this review. The use of applications for nutrition education is relatively new, and there is much research to be done.

Conclusion

A key finding in our review is that studies in LMICs reported important infrastructural and technical limitations to implement mHealth ranging from low network capacity, inadequate distribution of signal strength, and low access to mobile phones to specific technical barriers, such as delay in database updating. Also, only one study was identified evaluating primary anthropometric outcomes, indicating a need for more controlled studies of these primary endpoints. The review findings put relevance to the suggestion that cooperation between government organizations, academia, and industry is necessary to provide sufficient infrastructure support for mHealth use in LMICs. They also point to a need for enhanced strategies to motivate intervention participation by use of means such as newspaper and social media advertisements, health workers advice, and motivational gifts.

While several review studies have examined the role of mobile technology in nutritional interventions to promote proper diet and nutrition or to lose weight in adults [10, 16, 53] and adolescents [19], to the best of our knowledge, no reviews have focused on the role of mobile for addressing malnutrition (both under-nutrition and over-nutrition) issues for the sensitive age group of preschoolers which is critical in their growth and development. Furthermore, one featured points of our study is an almost comprehensive evaluation of the interventional articles in an extensive domain including users’ perceptions, technical and usability, usage and adoption factors and Efficacy of the intervention, which can provide significant opportunities for future research by concerning wide aspects.

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge Mr. Hamed Nadri (MSc in Medical informatics) for his great helps to retrieve data and to construct search strategy.

Funding

There was no funding associated with this research.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AWWs

Anganwadi Workers

- BITs

Behavioral Intervention Technologies

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CBSB

Cognitive Behavioral Skills Building

- E-Health

Electronic Health

- FMI

Fat Mass Index

- ICT

Information and Communication Technologies

- iOS

iPhone Operating System

- IYCF

Infant and Young Child Feeding

- LMICs

low- and middle-income countries

- M-Health

Mobile Health

- MINSTOP

Mobile-based Intervention Intended to Stop Obesity in Preschoolers

- MVPA

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

- PHM

Public Health Midwives

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- SMS

Short Message Service

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WIC

Women, Infants, and Children

Authors’ contributions

NS, BR, HRFE, TT and HLA took part in the data collection, analyses and manuscript writing. BR and NS in addition took part in the idea for the research. NS, BR, HRFE, TT and HLA made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; NS, BR, HRFE, TT and HLA have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it; all have given final approval of the version to be published; all agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Navisa Seyyedi, Email: ns.seyyedi@gmail.com.

Bahlol Rahimi, Phone: 00989128128119, Email: bahlol.rahimi@gmail.com.

Hamid Reza Farrokh Eslamlou, Email: hamidfarrokh@gmail.com.

Toomas Timpka, Email: toomas.timpka@liu.se.

Hadi Lotfnezhad Afshar, Email: hadi.afshar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kramer CV, Allen S. Malnutrition in developing countries. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;25(9):422–427. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders J, Smith T, Stroud M. Malnutrition and undernutrition. Medicine. 2015;43(2):112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faruque A, Ahmed AS, Ahmed T, Islam MM, Hossain MI, Roy S, et al. Nutrition: basis for healthy children and mothers in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(3):325. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v26i3.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Malnutrition 2017 [06 October 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/malnutrition/en/.

- 5.Hong SA, Winichagoon P, Mongkolchati A. Inequality in malnutrition by maternal education levels in early childhood: the prospective cohort of Thai children (PCTC) Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(3):457. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.032016.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammadinia N, Sharifi H, Rezaei M, Heydari N. The prevalence of malnutrition among children under 5 years old referred to health centers in Iranshahr during 2010-2011. J Occup Health Epidemiol. 2012;1(3):139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hien NN, Kam S. Nutritional status and the characteristics related to malnutrition in children under five years of age in Nghean, Vietnam. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41(4):232–240. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Psaki S, Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Ahmed S, Bessong P, Islam M, et al. Household food access and child malnutrition: results from the eight-country MAL-ED study. Popul Health Metrics. 2012;10(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delisle C, Sandin S, Forsum E, Henriksson H, Trolle-Lagerros Y, Larsson C, et al. A web-and mobile phone-based intervention to prevent obesity in 4-year-olds (MINISTOP): a population-based randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coughlin SS, Whitehead M, Sheats JQ, Mastromonico J, Hardy D, Smith SA. Smartphone applications for promoting healthy diet and nutrition: a literature review. Jacobs J Food Nutr. 2015;2(3):021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiaensen L, Alderman H. Child malnutrition in Ethiopia: can maternal knowledge augment the role of income? Econ Dev Cult Chang. 2004;52(2):287–312. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phengxay M, Ali M, Yagyu F, Soulivanh P, Kuroiwa C, Ushijima H. Risk factors for protein–energy malnutrition in children under 5 years: study from Luangprabang province, Laos. Pediatr Int. 2007;49(2):260–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloss E, Wainaina F, Bailey RC. Prevalence and predictors of underweight, stunting, and wasting among children aged 5 and under in western Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50(5):260–270. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.5.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadri H, Rahimi B, Timpka T, Sedghi S. The top 100 articles in the medical informatics: a bibliometric analysis. J Med Syst. 2017;41(10):150. doi: 10.1007/s10916-017-0794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahimi B, Nadri H, Afshar HL, Timpka T. A systematic review of the technology acceptance model in health informatics. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(03):604–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiFilippo KN, Huang W-H, Andrade JE, Chapman-Novakofski KM. The use of mobile apps to improve nutrition outcomes: a systematic literature review. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(5):243–253. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15572203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson CM. Behavioral nutrition interventions using e- and m-health communication technologies: a narrative review. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36(1):647–664. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Piao M, Byun A, Kim J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention for pediatric obesity using Mobile technology. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;225:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaplais E, Naughton G, Thivel D, Courteix D, Greene D. Smartphone interventions for weight treatment and behavioral change in pediatric obesity: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2015;21(10):822–830. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burrows TL, Khambalia AZ, Perry R, Carty D, Hendrie GA, Allman-Farinelli MA, et al. Great ‘app-eal’but not there yet: a review of iPhone nutrition applications relevant to child weight management. Nutr Diet. 2015;72(4):363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull P, Emerson JS, Quirk ME, Canedo JR, Jones JL, Vylegzhanina V, et al. A Smartphone App for Families With Preschool-Aged Children in a Public Nutrition Program: Prototype Development and Beta-Testing. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2017;5(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Nyström CD, Sandin S, Henriksson P, Henriksson H, Trolle-Lagerros Y, Larsson C, et al. Mobile-based intervention intended to stop obesity in preschool-aged children: the MINISTOP randomized controlled trial, 2. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2017;105(6):1327–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Shah MP, Kamble PA, Agnihotri SB, editors. Tackling child malnutrition: An innovative approach for training health workers using ICT a pilot study. Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10-HTC), 2016 IEEE Region 10; 2016:IEEE.

- 25.Weerasinghe MC, Senerath U, Godakandage S, Jayawickrama H, Wickramasinghe A, Siriwardena I, et al. Use of Mobile Phones for Infant and Young Child Feeding Counseling in Sri Lankan Tea Estates: A Formative Study. The Qualitative Report. 2016;21(5):899.

- 26.Militello LK, Melnyk BM, Hekler E, Small L, Jacobson D. Correlates of healthy lifestyle beliefs and behaviors in parents of overweight or obese preschool children before and after a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention with text messaging. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2016;30(3):252–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Denney-Wilson E, Laws R, Russell CG, Ong K-l, Taki S, Elliot R, et al. Preventing obesity in infants: the Growing healthy feasibility trial protocol. BMJ open. 2015;5(11):e009258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Charles TP, Yoshida C, editors. Factors affecting the adoption of ICT in malnutrition monitoring. Case study: Western Uganda. Computer and Information Science (ICIS), 2016 IEEE/ACIS 15th International Conference on; 2016: IEEE.

- 29.Umali E, McCool J, Whittaker R. Possibilities and expectations for mHealth in the Pacific Islands: insights from key informants. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(1):e9. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Källander K, Tibenderana JK, Akpogheneta OJ, Strachan DL, Hill Z, ten Asbroek AH, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) approaches and lessons for increased performance and retention of community health workers in low-and middle-income countries: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):e17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quelly SB, Norris AE, DiPietro JL. Impact of mobile apps to combat obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2016;21(1):5–17. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill SR, Vale L, Hunter D, Henderson E, Oluboyede Y. Economic evaluations of alcohol prevention interventions: Is the evidence sufficient? A review of methodological challenges. Health Policy. 2017;121(12):1249–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Drummond M, Brandt A, Luce B, Rovira J. Standardizing methodologies for economic evaluation in health care: practice, problems, and potential. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1993;9(1):26–36. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross J. The use of economic evaluation in health care: Australian decision makers' perceptions. Health Policy. 1995;31(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(94)00671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Handel MJ. mHealth (mobile health)—using apps for health and wellness. J Sci Healing. 2011;7(4):256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinnock H, Slack R, Pagliari C, Price D, Sheikh A. Understanding the potential role of mobile phone-based monitoring on asthma self-management: qualitative study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(5):794–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Story MT, Neumark-Stzainer DR, Sherwood NE, Holt K, Sofka D, Trowbridge FL, et al. Management of child and adolescent obesity: attitudes, barriers, skills, and training needs among health care professionals. Pediatrics. 2002;110(Supplement 1):210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis KE, Lahiri S, Brown KE. Targeting parents for childhood weight management: development of a theory-driven and user-centered healthy eating app. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e69. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gable S, Lutz S. Household, parent, and child contributions to childhood obesity. Fam Relat. 2000;49(3):293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jenkins C, Burkett N-S, Ovbiagele B, Mueller M, Patel S, Brunner-Jackson B, et al. Stroke patients and their attitudes toward mHealth monitoring to support blood pressure control and medication adherence. Mhealth. 2016;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.McGillicuddy JW, Weiland AK, Frenzel RM, Mueller M, Brunner-Jackson BM, Taber DJ, et al. Patient attitudes toward mobile phone-based health monitoring: questionnaire study among kidney transplant recipients. J Med Int Res. 2013;15(1):e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seto E, Leonard KJ, Masino C, Cafazzo JA, Barnsley J, Ross HJ. Attitudes of heart failure patients and health care providers towards mobile phone-based remote monitoring. J Med Int Res. 2010;12(4):e55. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pineros-Leano M, Tabb KM, Sears H, Meline B, Huang H. Clinic staff attitudes towards the use of mHealth technology to conduct perinatal depression screenings: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2014;32(2):211–215. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JE, Lee DE, Kim K, Shim JE, Sung E, Kang J-H, et al. Development of tailored nutrition information messages based on the transtheoretical model for smartphone application of an obesity prevention and management program for elementary-school students. Nutr Res Pract. 2017;11(3):247–256. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2017.11.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azar KM, Lesser LI, Laing BY, Stephens J, Aurora MS, Burke LE, et al. Mobile applications for weight management: theory-based content analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Int Res. 2010;12(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fogg BJ, editor A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th international Conference on Persuasive Technology; 2009: ACM.

- 50.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oinas-Kukkonen H, Harjumaa M. Persuasive systems design: key issues, process model, and system features. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. 2009;24(1):28. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Montague E, Burns MN, Rashidi P. The behavioral intervention technology model: an integrated conceptual and technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. J Med Int Res. 2014;16(6):e146. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Xue H, Huang Y, Huang L, Zhang D. A systematic review of application and effectiveness of mHealth interventions for obesity and diabetes treatment and self-management. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(3):449–462. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.