Abstract

Background

Glibenclamide is a second-generation oral sulfonylurea used to treat neonatal permanent diabetes mellitus. It is more effective and safer than the first-generation agents. However, no liquid oral formulation is commercially available and, therefore, it cannot be used for individuals who cannot swallow the solid form.

Objectives

To develop and study the physicochemical and microbiological stability of two liquid glibenclamide formulations for the treatment of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus: two suspensions (2.5 mg/mL)—one using glibenclamide raw material and the other, glibenclamide tablets. Furthermore, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) stability showed that the method is optimised and validated for analysis of glibenclamide in the formulations studied.

Methods

Samples were stored at 4°C, 25°C and 40°C. The amount of glibenclamide in each formulation was analysed in duplicate using HPLC at 0, 7, 14, 28, 60 and 90 days. Other parameters were also determined—for example, the appearance, pH and morphology. Microbiological studies according to the guidelines of the US Pharmacopoeia for non-sterile products at 0 and 90 days were carried out.

Results

All formulations remained physicochemically and microbiologically stable at three different temperatures during the 90-day study. Therefore, glibenclamide formulations can be stored for at least 90 days at ≤40°C.

Conclusions

These formulations are ideally suited for paediatric patients who usually cannot swallow tablets. The proposed analytical method was suitable for studying the stability of different formulations.

Keywords: PAEDIATRICS

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a heterogeneous group of disorders that can present from birth to old age. The most common forms, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, are polygenic in origin, whereas neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) and maturity-onset diabetes of the young are likely to have a monogenic cause. The monogenic forms of diabetes may account for as much as 1–2% of all cases of diabetes and are primary genetic disorders of the insulin-secreting pancreatic β cell. NDM is rare, reportedly affecting ∼1 in 500 000 infants worldwide (although possibly having an incidence as high as 1 in 100 000 infants) and typically presents within the first 3 months of life.1–2

Two clinical subgroups that define the duration of the disease are transient NDM and permanent NDM, each believed to be caused by various genetic mutations. Presenting characteristics in infants include intrauterine growth retardation, reflecting insulin's role as a prenatal growth factor, and small for gestational age.3

Until recently, both transient and permanent NDM were treated solely with subcutaneous insulin, which some caregivers find difficult to manage. Studies of the mutant proteins in vitro suggested that it would be possible to treat NDM with oral sulfonylureas rather than insulin, owing to their ability to block K/ATP channels.4–8

Glibenclamide (5-chloro-N-[2-[4-(cyclohexylcarbamoylsulfamoyl)phenyl]ethyl]-2-methoxybenzamide), is a second-generation oral sulfonylurea and has been the most widely used sulfonylurea in the treatment of NDM.4–6 8 It has been shown that glibenclamide is more effective and safer than the first-generation agents.9 However, because there is no commercially available liquid oral formulation for this drug, its use is limited in infants and children aged ≤5 years who cannot swallow a solid form (eg, tablet, capsule). Use of a solid form of the drug containing a fixed dose would also be impractical in these patients because the dosage requirements vary according to patient characteristics, type of mutation and time of transfer from insulin to sulfonylurea. Thus, pharmaceutical liquids, rather than solid forms, are preferred for oral administration to infants and young children, reducing potential dosage mistakes, and helping adherence to treatment. A single liquid paediatric preparation may be used for infants and children of all ages, with the dose of the drug varied by the volume administered.10 The availability of liquid formulations enables paediatricians to apply the dosing regimen established by the transfer protocol of Andrew Hattersley.11

The aim of this study was to develop two glibenclamide liquid oral formulations of the same concentration—one using glibenclamide raw material and the other, using glibenclamide tablets. We optimised and validated a stability-indicating high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method for the glibenclamide analysis in order to study the physicochemical and microbiological stability of glibenclamide in the proposed formulations stored at three different temperatures over 90 days.

Methods

Materials

Glibenclamide tablets (Daonil 5 mg, Sanofi—Aventis Argentina S.A., batch 1L003M) were obtained from the hospital pharmacy (Pediatric Hospital J.P. Garrahan, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Glibenclamide raw material (Magel, batch GC090506; BP quality) was purchased from Magel S.A. (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Supply of other agents was as follows: sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC sodium) of high viscosity (V. Rossum, batch 04051), xanthan gum (Magel S.A., batch 585/2007), methylparaben (Nipagin) (Magel S.A., batch IA2011), propylparaben (Nipasol) (Chutrau, batch GBGA028779), glycerin (Prest, batch 130520), saccharine sodium (Magel S.A., batch L20130403), sorbitol 70% solution (Prest, batch E968E), anhydrous citric acid (Magel S.A., batch 6021241), propylene glycol (Magel S.A., batch 907311760). All excipients were US Pharmacopeia (USP) quality. Solvents of HPLC grade and other reagents were used as received.

Preparation of formulations

Two glibenclamide suspensions (2.5 mg/mL) were prepared—one (suspension A) using glibenclamide tablets and the other (suspension B), using glibenclamide raw material. Both formulations were prepared by placing glibenclamide tablets or raw powder on a mortar and levigated with the corresponding vehicle. Table 1 shows the excipients used for each vehicle. All the trial formulations were stored in amber glass vials and kept at three temperatures—controlled room temperature (25°C), refrigerated (4°C) and accelerated conditions (40°C)—during the stability study.

Table 1.

Excipients used in glibenclamide formulations

| Formulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical | Functional | (% w/v) | |

| excipient | category | A | B |

| CMC sodium | Suspending agent | 0.80 | |

| Xanthan gum | Suspending agent | 0.20 | |

| Methylparaben | Antimicrobial preservative | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Propylparaben | Antimicrobial preservative | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Glycerin | Humectant | 5.00 | |

| Saccharine sodium | Sweetening agent | 0.20 | |

| Sorbitol 70% solution | Humectant and sweetening agent | 25.00 | |

| Citric acid anhydrous | pH regulator | 0.10 | |

| Propylene glycol | Cosolvent | 0.60 | |

| Distilled water | Vehicle | q.s. | q.s. |

CMC, carboxymethylcellulose; q.s., quantum satis—that is, the amount which is needed.

Vehicle preparation for suspension A

The aqueous vehicle for suspension A consisted of methylparaben, propylparaben, xanthan gum and distilled water. This vehicle was prepared by dissolving the parabens in a portion of distilled water previously heated to 90°C. Xanthan gum was placed in a mortar and levigated with the preserved water previously cooled to 25°C. Finally, the contents were transferred into a graduated flask and distilled water added to achieve the final volume. The final pH (5.8) of the vehicle was carefully monitored and adjusted if necessary.

Vehicle preparation for suspension B

The vehicle for suspension B consisted of CMC, glycerin, sorbitol 70% solution, sodium saccharine, anhydrous citric acid, propylene glycol, methylparaben, propylparaben and distilled water as solvent. To prepare this vehicle, the first step was to dissolve the parabens in propylene glycol. Sodium saccharine and citric acid were dissolved in a portion of distilled water. CMC was moistened in glycerin and mixed until full dispersion, and then sorbitol was added. All parts were mixed together, transferred into a graduated flask and distilled water added to achieve the final volume. The final pH (4−5) of the vehicle and the density (around 1.08 g/mL) were carefully monitored.

Physicochemical characterisation of formulations

Three 30 mL aliquots of the suspensions for each study point (0, 7, 14, 28, 60 and 90 days) were stored in amber glass containers at three different temperatures (4, 25 and 40°C) for 90 days. Measures which might change during the storage period, such as appearance, redispersibility, pH, particle morphology and drug concentration, were made at different times. Preparations were considered stable if the physical properties had not changed and the drug concentration had remained between 90 and 110% of the original concentration.

Appearance test

The physical appearance of the samples stored at each temperature was examined visually; odour and colour were monitored throughout the study.

Resuspendability

The time taken for the suspension to redisperse completely was determined after the samples had been vigorously shaken to redistribute the sediment and the result was expressed in seconds.

pH measurements

pH values were measured using a digital pH/mV meter IQ 140 (IQ Scientific Instruments, California, USA). Measurements were made at 0, 7, 14, 28, 60 and 90 days in triplicate and the results were averaged.

Morphology

The morphological analysis of glibenclamide suspended particles was carried out by optical microscopy (Trinocular Microscope Arcano XSZ-107 E, Arcano, China) using a photographic digital camera. The photos were analysed using TSView V.6.2.4.5 for Windows.

Analytical method

The chromatographic system consisted of an isocratic solvent delivery pump (Thermo Scientific SpectraSystem P4000, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with a 150 mm×4.6 mm reverse phase column C18 particle diameter 5 µm (Thermo Scientific). The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of acetonitrile and KH2PO4 1.36% w/v pH=3 (47:53) with a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The column temperature was set at 25°C. Ten microlitres of each sample were introduced into the column using an automatic injector (Thermo Scientific SpectraSystem AS3000). The column effluent was monitored with a wavelength ultraviolet detector (Thermo Scientific SpectraSystem UV2000) set at 300 nm. According to the stability study design, two aliquots were collected from each of the three containers at each temperature on days 0, 7, 14, 28, 60 and 90 after mixing (10 times inverted by 180°). These samples were diluted with methanol, sonicated for 10 min and centrifuged for 5 min to separate the insoluble components. A final dilution was prepared from the supernatant obtained in the previous centrifugation step, with a mixture of methanol:water (6:1) to obtain a concentration of 100 µg/mL; the resultant solutions were immediately analysed. An external reference standard solution was prepared by solubilising glibenclamide in methanol and then final dilution in a mixture of methanol:water (6:1) to obtain a concentration of 100 µg/mL. In all cases, the final concentration of the glibenclamide working standard solutions was 100 µg/mL.

Validation of the analytical method

The method was validated by studying the specificity, linearity, precision, limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) and accuracy.12 First, specificity was evaluated by subjecting glibenclamide standard to different possible degradation routes with HCl 0.5 M, NaOH 0.5 M, H2O2 3% 48 h, and light for 1 week, which were then analysed by HPLC. Additionally, blank samples with all the excipients involved were prepared and analysed to check for interference. Second, the linearity of the proposed method was evaluated by establishing a relationship between the concentrations of glibenclamide and areas on the standard chromatogram. This is shown by linear regression models obtained for each of the two standard preparations. Linearity was verified at five concentrations (50, 75, 100, 125 and 150 µg/mL) of glibenclamide, prepared in blank of excipients for each formulation and these were analysed in duplicate in three separate runs. Third, LOD and LOQ were determined based on signal-to-noise ratio. A relation of 3:1was used for estimating the LOD, whereas a 10:1 relation was used for the LOQ. Finally, precision was evaluated for intraday (n=6) and interday assays (n=18) and expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) for retention times and areas. Accuracy was evaluated from recovery studies of samples of glibenclamide from their matrix. Placebo samples prepared with all the excipients contained in each of the different pharmaceutical formulations, at concentration levels of 80, 100 and 120% (w/v) of the nominal values, were spiked with glibenclamide. All parameters were determined for each formulation.

Microbiological studies

Microbiological tests of formulations were performed at 0 and 90 days according to the USP monograph of non-sterile products for oral administration.13 The microbial count was considered to be the average number of colony-forming units (cfu) found in agar. Liquid oral formulations were considered to meet microbial requirements if the total aerobic microbial count was <102 cfu/mL, the total combined yeast/mould count was <10 cfu/mL and the absence of Escherichia coli were confirmed.

Results

Two different oral liquid formulation suspensions have been developed: suspension A using glibenclamide from commercial tablets, and suspension B glibenclamide from raw material. Results from different physical, chemical and microbiological studies are presented.

In the appearance test, after preparation (t=0) both formulations were white suspensions, with no characteristic odour. No changes in colour or odour were detected in any sample during the 3 months of storage at the three controlled temperatures.

All formulations were resuspendible, since the sediments were easily redispersed after 10 s of vigorous manual agitation, resulting in a homogeneous system at all temperatures and times.

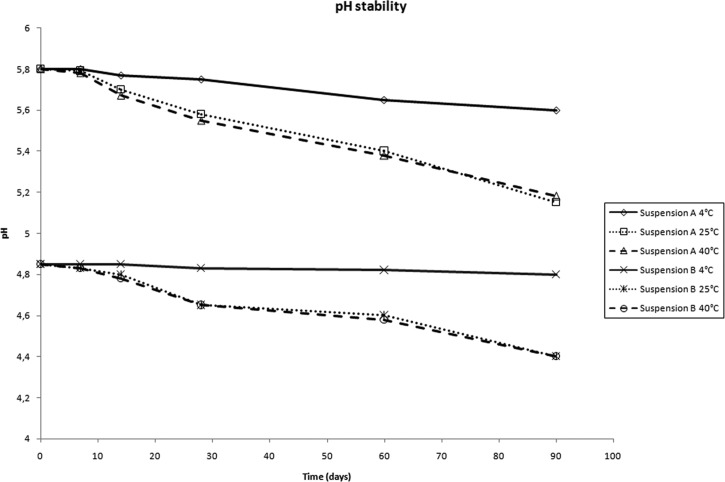

The results of pH monitoring are shown in figure 1 for both formulations (suspension A, 5.8–5.2 and suspension B, 4.8–4.4).

Figure 1.

pH values throughout the stability study period for both formulations at 4, 25 and 40°C.

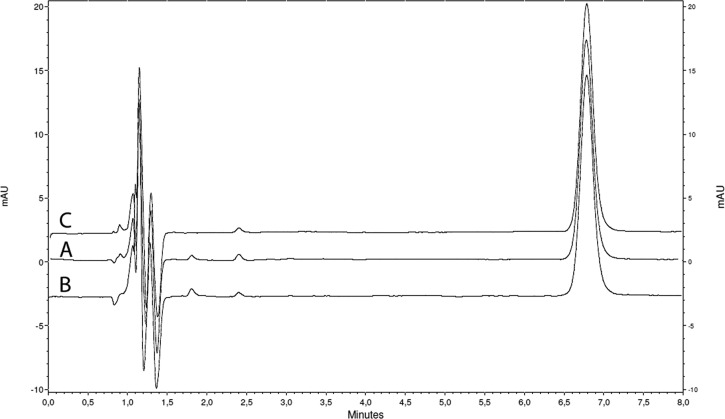

The chromatograms corresponding to both formulations and the standard solution of glibenclamide are presented in figure 2. Glibenclamide retention time was 6.8 min. No degradation products were seen under the established conditions in all cases. However, a related substance was seen at 2.4 min in both formulations and the standard solution, from the beginning of the analysis (day 0), which remained unchanged until the end of the study. However, the content of this related substance was <0.5% w/w and 1.0% w/w (with respect to the glibenclamide) for suspensions A and B, respectively. Parameters validating the method of analysis are presented in table 2.

Figure 2.

Chromatograms of (A) glibenclamide suspension A; (B) glibenclamide suspension B; (C) glibenclamide standard solution. All samples were studied at the same concentration (100 µg/mL).

Table 2.

Parameters validating the method of analysis of glibenclamide

| Parameter | Suspension A | Suspension B |

|---|---|---|

| Linear range (µg/mL) | 50.0–150.0 (y=2175.5x−7699) |

50.0–150.0 (y=2127x−7615) |

| R2 | 0.9927 | 0.9951 |

| LOD (µg/mL) | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| LOQ (µg/mL) | 0.62 | 0.74 |

| Precision (% RSD) | ||

| Intraday (n=6) | ||

| Retention time | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Peak area | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Interday (n=18) | ||

| Retention time | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Peak area | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Accuracy | ||

| Spiked levels | ||

| 80% | 100.7 (RSD=1.3) | 106.0 (RSD=1.8) |

| 100% | 99.2 (RSD=0.8) | 103.7 (RSD=1.1) |

| 120% | 102.5 (RSD=1.9) | 105.9 (RSD=2.3) |

LOD, limits of detection; LOQ, limits of detection quantification; RSD, relative standard deviation.

Table 3 shows the stability results for each formulation, all of which were stored in refrigerated conditions (4°C), room temperature (25°C) and accelerated conditions (40°C), expressed as mean percentage of the initial glibenclamide concentration.

Table 3.

Stability of glibenclamide suspensions stored at 4, 25 and 40°C

| Time (days) | Suspension A | Suspension B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 25°C | 40°C | 4°C | 25°C | 40°C | |

| 0 | 100.1 (0.6) | 100.2 (0.8) | ||||

| 7 | 102.3 (0.9) | 100.5 (1.1) | 97.3 (1.7) | 99.4 (0.8) | 98.7 (1.6) | 95.1 (0.5) |

| 14 | 101.4 (0.6) | 102.5 (1.4) | 100.6 (0.3) | 100.8 (1.1) | 97.1 (2.5) | 95.7 (0.4) |

| 28 | 100.7 (1.2) | 94.7 (1.9) | 103.8 (1.5) | 101.6 (1.4) | 99.1 (1.1) | 94.9 (0.7) |

| 56 | 103.3 (2.1) | 97.6 (0.8) | 105.3 (0.8) | 104.2 (0.3) | 101.3 (1.2) | 96.9 (0.8) |

| 84 | 103.5 (0.7) | 99.1 (1.6) | 97.7 (1.0) | 98.8 (0.5) | 102.9 (0.5) | 94.9 (1.8) |

*Mean percentage of the initial glibenclamide concentration and relative standard deviation in parentheses (n=3).

Evaluation of the microbial study for both formulations showed no E. coli contamination and a total bacteria count of <102 cfu/mL on days 0 and 90 of the study. Fungal contamination was also <2 cfu/mL on days 0 and 90 for both formulations.

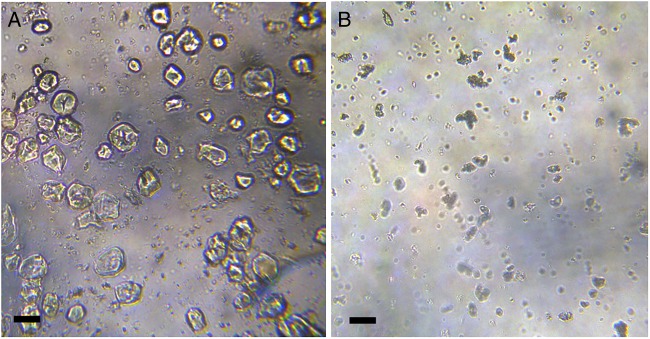

Morphological characterisation of the suspended glibenclamide particles is shown in figure 3. Formulation B exhibits smaller particle size, whereas formulation A suspended particles are irregular and predominantly larger.

Figure 3.

Microphotographs of glibenclamide suspensions prepared from (A) commercially available tablets and (B) pure drug. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Discussion

Development of the formulations

Preliminary studies investigated the development of a glibenclamide solution with a high concentration of cosolvent such as propylene glycol (up to 100%), polyethyleneglycol (PEG) 400 (up to 100%) and sorbitol 70% solution (up to 100%). Glibenclamide appears to be very soluble in propylene glycol and PEG 400 but not in sorbitol 70% solution. However, the drug precipitates in propylene glycol at 100% after a month. Moreover, heating is required to solubilise the drug and a yellow colouration and several products of degradation (determined by HPLC) appear after the drug is solubilised with heat in PEG 400, so this practice was discarded. To develop a suitable formulation for children, a glibenclamide solution with non-toxic percentages of cosolvents such as propylene glycol, PEG 400–4000, glycerin and sorbitol 70% solution was investigated with no success, since the drug precipitated after a few days, probably owing to the presence of water in the formulation, in which glibenclamide is highly insoluble.

Therefore, an aqueous suspension was next investigated. Suspensions are useful forms for administering poorly water-soluble drugs. Moreover, a suspension can mask the unpleasant taste of glibenclamide, improving paediatric treatment adherence. Therefore, we developed and studied two different suspensions, one using the pure drug (suspension B) and the other using tablets (suspension A), in case the pure drug was not available.

The aim of this study was to develop an optimal oral liquid glibenclamide formulation, easy to prepare and physicochemically and microbiologically stable for use when a solid form is not suitable. Only one study has reported details of glibenclamide oral liquid formulations prepared only from tablets and described their chemical stability over 90 days.14 Our study adds more information, with raw material based formulations and microbiological studies, together with other important characteristics, such as colour, odour, resuspendibility, pH, chemical stability and morphology of suspended particles.

The formulation design was aimed at developing a simple dosage form, using a single suspending agent. Xanthan gum was the preferred vehicle for formulation A (using glibenclamide tablets), based on a previous work in which we used it as an emulsifying agent in a liquid oral formulation.15 Xanthan gum is widely used in oral and topical pharmaceutical and cosmetic formulations as a suspending and stabilisation agent. It is non-toxic, compatible with most other pharmaceutical ingredients, and has good stability and viscosity properties over a wide range of pH and temperatures.16 Along with xanthan gum, a preservative agent was added. Parabens were a suitable choice since they are widely used.

Formulation B, based on glibenclamide raw material, required a multi-ingredient vehicle. CMC was used as suspending agent with excellent results, glycerin as humectant and parabens as preservative agents; a pH regulator and sweetening agents were also added. A small percentage of propylene glycol was used as cosolvent.

Stability study

Colour is an important attribute in pharmaceutical products since it is immediately perceived by the consumer. It can also indicate reactions in a drug since degraded compounds may contribute to a specific colouration. In the developed formulation, no colour or odour changes were seen.

Suspension resuspendibility was easy and homogeneous at every time and temperature tested.

pH monitoring is an important aspect of a stability study, since the pH of non-buffered vehicles may change over time. In some cases, these changes may increase the rate at which degradation products are formed or modify the appearance. In this case, only slight changes in pH values were seen over time and at every temperature for both formulations (figure 1).

This study also investigated glibenclamide chemical stability under different storage conditions. In general, oral formulations such as suspensions should contain >90% and <110% of the labelled amount of drug. Both formulations (A and B) had an acceptable drug chemical stability, where the glibenclamide content remained >90% at the three temperatures for a period of 90 days. The analytical method used for this stability study was validated according to international guidelines.12 The proposed analytical method was specific without interference from excipients and degradation products demonstrated by stress study. The impurity seen on the chromatogram of both glibenclamide standard solution and the suspensions was similar, representing 0.5% to 1.0% w/w, which remained unchanged until the end of the study. The content of this impurity is in agreement with pharmacopoeia specifications (USP and European Pharmacopoeia (EP)).17 18

Linearity was evaluated from 50.0 µg/mL to 150 µg/mL with adequate R2 as well as LOD and LOQ values, for both formulations. Precision was evaluated intraday (n=6) and interday (n=18) and expressed as RSD for retention time and peak area. The RSD values obtained were <2.5%. Method accuracy was determined by a recovery study at three levels. The recovery values were good with low RSD (table 2).

Microbiological stability is important, and these formulations proved to be safe, preventing diseases related to bacterial and fungal contamination, which is a critical aspect when treating paediatric and neonatal patients and especially important for immunocompromised patients. Moreover, microbial contamination in non-sterile liquid formulations may cause a foul odour, turbidity and adversely affect the palatability and appearance. For both formulations no E. coli contamination was seen and the total bacteria count was <102 cfu/mL on day 90 of the study. Fungal contamination was also <102 cfu/ml in both formulations. These results indicated that both formulations complied with the USP and EP specifications on microbial examination of non-sterile products throughout 90 days.19 20

The microscopic aspect of the samples was also evaluated. Formulation A, which was prepared from commercially available tablets, had a greater amount of suspended particles probably owing to the presence of water-insoluble pharmaceutical additives in the tablets. Particle size in this case was larger and irregular, which might have been influenced by the previous particle size of the active ingredient, determined by compression forces in the tablet manufacturing process. When glibenclamide raw material (formulation B) was used, particle size was smaller and regular. The particle size for both formulations was constant throughout the test period at different temperatures.

Conclusion

Paediatric oral liquid glibenclamide suspensions had adequate physical and chemical stability, keeping glibenclamide particles homogeneously distributed and therefore guaranteeing that the correct dose could be given to paediatric patients. These formulations can be stored at a paediatric hospital or pharmacy without special conditions. Both formulations are safe and are alternatives, depending on the availability of pure drug or tablets. The availability of a liquid formulation enables paediatricians and pharmacists to vary the dose from patient to patient, and treat patients who cannot swallow tablets or other solid forms. However, although both formulations have physical, chemical and microbiological stability, it is preferable, if possible, to prepare a suspension based on the raw material to ensure the correct active pharmaceutical ingredient concentration in the formulation. A good alternative is the tablet-based suspension.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

Glibenclamide, a second-generation oral sulfonylurea, used to treat neonatal permanent diabetes mellitus is more effective than the first-generation agents.

Glibenclamide is commercially available as oral solid formulations containing a fixed dose.

Glibenclamide is unsuitable for patients unable to swallow a solid form such as tablets or capsules.

Diseases such as diabetes often require dose adjustments according to patient characteristics.

What this study adds

Development of oral liquid paediatric suspensions.

Complete chemical and microbiological stability study of the developed formulations.

Development, optimisation and validation of the analytical method for quantification of glibenclamide in the suspensions.

Ideal dosage adjustment for paediatric patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support by University of Buenos Aires and CONICET.

Footnotes

Contributors: PE: contributed to experimental and analysis of the formulations. OB: contributed to experimental and analysis of the formulations. PRF: contributed to experimental and analysis of the formulations. PQ: microbiological analysis. FB: design of experiments and interpretation of data. VT: design of experiments and interpretation of data. SL: design of experiments and interpretation of data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Eide S, Raeder H, Johansson S, et al. Prevalence of HNF1A (MODY3) mutations in a Norwegian population (the HUNT2 Study). Diabet Med 2008;25:775–81. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy R, Ellard S, Hattersley A. Clinical implications of a molecular genetic classification of monogenic beta-cell diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008;4:200–13. 10.1038/ncpendmet0778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperling M. The genetic basis of neonatal diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2006;4:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagen J, Hathout E, Shehadeh N, et al. Permanent neonatal diabetes due to mutations in KCNJ11 encoding Kir6.2: patient characteristics and initial response to sulfonylurea therapy. Diabetes 2004;53:2713–18. 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zung A, Glaser B, Nimri R, et al. Glibenclamide treatment in permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus due to an activating mutation in Kir6.2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:5504–7. 10.1210/jc.2004-1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Codner E, Flanagan S, Ellard S, et al. High-dose glibenclamide can replace insulin therapy despite transitory diarrhea in early-onset diabetes caused by a novel R201L Kir6.2 mutation. Diabetes Care 2005;28:758–9. 10.2337/diacare.28.3.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hathout E, Mace J, Bell G, et al. Treatment of hyperglycemia in a 7-year-old child diagnosed with neonatal diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1458 10.2337/dc06-0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson E, Flechtner I, Njølstad P, et al. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations. N Engl J Med 2006;355:467–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa061759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng Y, Li M, Chen Y, et al. The use of glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Adv Med Sci 2014;59:95–101. 10.1016/j.advms.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahata M, Allen L. Extemporaneous drug formulations. Clin Ther 2008;30:2112–19. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diabetes Research Department and the Centre for Molecular Genetics, University of Exeter Medical School. Transferring patients with diabetes due to a Kir6.2 mutation from insulin to sulphonylureas, 2007. http://www.diabetesgenes.org.

- 12.Guidance Q2 (R1), Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology. International Conference on Harmonization Final version 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. United States Pharmacopeia, USP 31, NF 26, Rockville, MD, USA, 2009, 76–85.

- 14.Di Folco U, De Falco D, Marcucci F, et al. Stability of three different galenic liquid formulations compounded from tablet containing glibenclamide. Journal of Nutritional Therapeutics 2012;1:152–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estevez P, Tripodi V, Buontempo F, et al. Coenzyme Q10 stability in pediatric liquid oral dosage formulation. Farm Hosp 2012;36:492–7. 10.7399/FH.2012.36.6.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hippalgaonkar K, Majumdar S, Kansara V. Injectable lipid emulsions—advancements, opportunities and challenges. Pharm Sci Tech 2010;11: 1526–40. 10.1208/s12249-010-9526-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Pharmacopeia, USP 31, NF 26, Rockville, MD, USA, 2009, 2282.

- 18.European Pharmacopoeia, EP 5.0, Strasbourg, France, 2004, 1659.

- 19.United States Pharmacopeia, USP 31, NF 26, Rockville, MD, USA, 2009, 578–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Pharmacopoeia, EP 6.0, Strasbourg, France 2008, 528–9.