Abstract

Objective

The individualised patient prescription chart, either paper or electronic, is an integral part of communication between healthcare professionals. The aim of this study is to ascertain the extent to which different prescribing systems are used for inpatient care in acute hospitals in England and explore chief pharmacists' opinions and experiences with respect to electronic prescribing and medicines administration (EPMA) systems.

Method

Audio-recorded, semistructured telephone interviews with chief pharmacists or their nominated representatives of general acute hospital trusts across England.

Results

Forty-five per cent (65/146) of the chief pharmacists agreed to participate. Eighteen per cent (12/65) of the participants interviewed stated that their trust had EPMA systems fully or partially implemented on inpatient wards. The most common EPMA system in place was JAC (n=5) followed by MEDITECH (n=3), iSOFT (n=2), PICS (n=1) and one in-house created system. Of the 12 trusts that had EPMA in place, 4 used EPMA on all of their inpatient wards and the remaining 8 had a mixture of paper and EPMA systems in use. Fifty six (86% 56/65) of all participants had consulted the standards for the design of inpatient prescription charts. From the 12 EPMA interviews qualitatively analysed, the regulation required to provide quality patient care is perceived by some to be enforceable with an EPMA system, but that this may affect accuracy and clinical workflow, leading to undocumented, unofficial workarounds that may be harmful.

Conclusions

The majority of inpatient prescribing in hospital continues to use paper-based systems; there was significant diversity in prescribing systems in use. EPMA systems have been implemented but many trusts have retained supplementary paper drug charts, for a variety of medications. Mandatory fields may be appropriate for core prescribing information, but the expansion of their use needs careful consideration.

Keywords: PHARMACY MANAGEMENT (ORGANISATION, FINANCIAL); QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

EAHP Statement 4: Clinical Pharmacy Services.

EAHP Statement 5: Patient Safety and Quality Assurance

Introduction

The prescribing of medicines is the most common form of therapeutic intervention in healthcare and is fundamental to high-quality patient care.1 On admission to hospital, each patient is assigned a paper or electronic prescription chart, which has the purpose of communicating information within and across healthcare teams, including which medications have been, or will be, given to the patient. The details of the medicine are entered on to the paper or electronic prescription chart, and additional sections prompt the prescriber to include all relevant details, making it unique to an individual inpatient.2 This individualised prescription chart, used by key healthcare professionals (HCPs), is the basis for medicine review, supply and administration.

UK hospital inpatient prescribing systems are based on a paper-based model, established some 60 years previously and have remained largely unchanged.3 This paper-based model uses paper prescription charts such as ‘Aberdeen sheets’,4 ‘drug charts’ or ‘medication Kardex’.5 Currently, there are no standardised national paper-based prescription charts across England. Therefore, NHS regions and Trusts have developed their own inpatient paper-based prescription charts, each with varying standards.6–9 While paper prescription charts are low cost and do not require extensive user training, their main problems are handwriting legibility and incomplete sections. These issues result in HCPs seeking clarification from prescribers regarding the prescribing intention.10 The publication of Standards for the design of hospital inpatient prescription charts encouraged a move towards a standard prescription chart to be used across England.11 The design standards outlined the expectations that should be met by an optimal prescription chart (paper and electronic). However, it is not yet known how widespread the use of the standards is across England.

The term ePrescribing, used throughout both primary and secondary care within the UK, is a broad term. An electronic prescribing and medicines administration (EPMA) system is a specific ePrescribing system that must facilitate both inpatient prescribing and the administration of medications in hospitals. It is the closest electronic equivalent to the paper prescription chart. In the last decade, acute trusts have started to implement EPMA systems.

EPMA is advocated as reducing prescribing errors (particularly those due to illegibility) and supporting the efficient management of medicines for both patient and trust.3 The NHS Connecting for Health guidelines12 recognised that although EPMA systems are able to reduce certain prescription errors they have introduced new types of error, such as where an incorrect medicine is mistakenly selected from the in-built list when prescribing.12 The extent and nature of the new error types and how they can be robustly identified is still unclear.13–18

Research into the implementation of EPMA systems is limited to convenience sample surveys during conferences19 self-administered postal questionnaires20 or surveys.21 Studies prior to 2011 indicate that hospitals had a high interest in EPMA, but only a small number had actually implemented systems.19 22 In 2013, the NHS Commissioning Board set out a clear expectation that hospitals should make better use of information and technology by 2018.23 However, only a small fraction of UK trusts use inpatient EPMA systems across all adult medical and surgical wards,20 a situation that is also reflected in Europe and the USA.21 24

Aim of the study

To ascertain the extent to which different prescribing systems are used for inpatient care in acute hospitals in England and explore chief pharmacists' opinions and experiences with respect to EPMA systems.

Method

Audio-recorded semistructured telephone interviews with chief pharmacists or their nominated representatives, of general acute hospital trusts across England, were undertaken during the period January–February 2012. Each chief pharmacist25 received the study information and a letter inviting them to participate before contact by telephone was made. Institutional Research Ethic Committee approval was obtained prior to recruitment (Ref: 11/PBS/014; date of approval: 01/12/2011). Telephone interviews enabled the researcher to obtain a good response and contact a large number of potential participants across England, therefore saving time and money. The recruitment procedure and the structured telephone interview questions were the subject of a pilot to ensure clarity and appropriateness.

Verbal informed consent, incorporated in the telephone interview schedule, was obtained after the research had been explained to potential participants. The semistructured interviews included both open and closed questions, one section covered the prescribing systems used in the trust (see online supplementary file). Tick boxes were used to record answers to the closed questions; responses to open questions were transcribed from the recording with any identifiable information removed. A unique recording number was allocated to each participant and the corresponding transcripts and recordings.

ejhpharm-2016-000905supp001.pdf (311.9KB, pdf)

Quantitative data were transferred into an Excel document for analysis. Transcription was independently checked for quality assurance purposes prior to analysis. Qualitative thematic analysis was carried out using a grounded theory approach on the EPMA interviews; data saturation was achieved. The quotations supplied in the text to illustrate the emergent themes provide the relative size of the trusts and the number allocated to maintain anonymity.

Results

At the time of data collection, there were 146 non-specialist acute trusts within England, comprising 29 small, 49 medium, 42 large and 26 teaching organisations.25 Of the 146 chief pharmacists contacted, 65 (45%) acute hospital trusts agreed to participate. Interviews were thematically analysed from trusts using EPMA (12/65), the findings relate only to the EPMA content of the interviews.

Prescribing systems in use

Of the 53 trusts (82%, 53/65) that had a paper drug chart in place, 34 (64%, 34/53) planned to implement or change to EPMA in the future. Forty one (77%, 41/53) of those trusts using paper charts had reviewed and updated the chart within the previous 2 years of conducting the interviews. Of these, eight stated that reviews were being/had been conducted in light of the recent publication of the Standards for the design of hospital inpatient prescription charts. 11 All participants were asked if they had considered the publication; only nine (13.8%, 9/65) had not considered the publication, three of which were trusts that had implemented EPMA.

Twelve (18%) of the 65 participants interviewed stated that their trust had EPMA fully or partially implemented on inpatient wards. The most common EPMA system in place was JAC (n=5) followed by MEDITECH (n=3), iSOFT (n=2), PICS (n=1) and one in-house created system. Four trusts had implemented ePrescribing within the last 2 years. Three of these trusts had implemented the JAC system and the other had implemented the Meditech system.

Of the 12 trusts that had EPMA in place, 4 used it on all of their inpatient wards and the remaining 8 trusts had a mixture of paper and EPMA systems in use. Eleven of those 12 trusts with EPMA also used supplementary paper charts to varying extents. Supplementary charts were used for intravenous infusions,9 insulin,10 warfarin8 and tapering doses.4 There were eight other supplementary charts reported for various other uses.

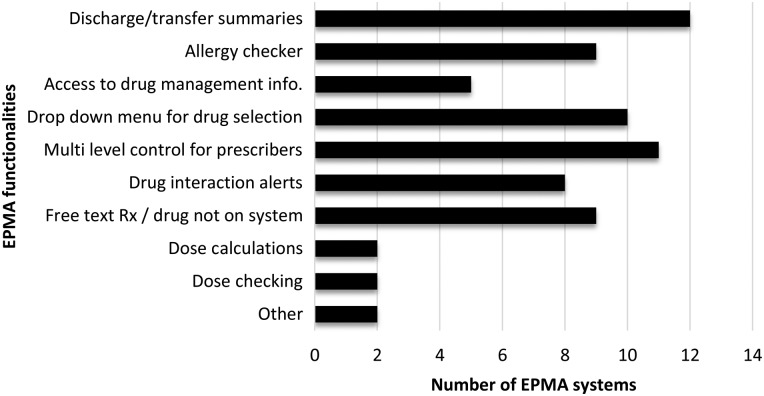

Participants in trusts with EPMA were asked about those functionalities of the systems that they felt were important at improving prescribing quality. The function most commonly reported as beneficial was the use of discharge summaries or patient transfers (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electronic prescription chart functionalities provided by the electronic prescribing and medicines administration (EPMA) software (n=12). Multilevel control for prescribers—the EPMA system can limit prescribing depending on prescriber experience or specialty.

The perceived impact of EPMA systems

Three themes emerged from the qualitative data, Regulation, Clinical workflow and Patient safety, which are interconnected, as identified by the quotes below.

Regulation: equitable and effective

A number of participants (8/12) indicated that EPMA systems enabled control and timely feedback that was not previously possible with a paper-based system. Indeed, at one hospital, the EPMA system had enabled the feedback of live data to frontline staff via a quality dashboard. However, this had led to more pressures on staff with the extent of the regulation negatively affecting them.

We have some extremely comprehensive quality dash boards…There is also a lot of pressure internally now both on the nurses and the medics because of course the reporting capability within the system (EPMA) means there is nowhere to hide. (Teaching 1)

EPMA systems were also considered to help enforce policies and controls through mandatory fields. Interestingly, policies that were put in place prior to implementation of EPMA were questioned once enforced, suggesting that these policies had not previously been acknowledged or followed when a paper prescribing system was in place. This may have reflected the extensive work of preparing for ePrescribing, which was considerably more than that undertaken before the introduction of a paper drug charts.

We did a huge amount of work [with ePrescribing]…. getting the clinicians to agree on what needs to go on, in what way and what's the protocols… you kind of get people together to talk about these things and having to compromise. In itself that is quite a good quality initiative, if you had only done that for paper well, it is very hard to get people to comply then isn't it. (Teaching 2)

The use of regulation seeks to promote effective and equitable care. However, for regulation to be effective, guidelines, policies and procedures must be followed. There were mixed experiences reported with respect to EPMA effectiveness at enforcing policies within an inpatient prescribing system. The prescriber is forced, by having mandatory fields in place, to complete all the required fields; this creates an effective mechanism, when compared with paper prescribing systems, to enforce policies and guidelines, yet it could lead to the entry of incorrect information. This became apparent when HCPs (doctors, nurses and pharmacists) appeared to first become aware of some policies when they were made compulsory through the EPMA system. Respondents in trusts with EPMA reported workarounds being evident in the working practices of their staff, where staff bypass the mandatory fields to streamline their workflow, which may lead to the input of inaccurate or misleading information.

Clinical workflow: timely, efficiency and patient centred

The theme of clinical workflow considered the challenges and benefits encountered regarding time and efficiency. The time taken to use the system for prescribing and administration had increased, yet time savings were encountered in other activities, such as audit.

With EPMA facilitating feedback, it was mandatory to complete all prescription fields. However, this had led to an increase in time completing a prescription. The opportunities afforded by EPMA systems were recognised, but this needed to be balanced with the wider impact of changing working practices.

The beauty of it (EPMA) is you can make it do so many things, so we could actually make it half an hour to prescribe a single drug if we wanted to. So it becomes a balance between workflow, audit information and safety info. So it's about balance along the line, it probably doesn't have a bearing on for one drug it's when it becomes routine. (Large 3)

Just prior to the interviews taking place, a national shortage of a drug occurred; one of the interviewees explained how EPMA was a benefit regarding time and efficiency in terms of implementing a switch to another available product.

Had we been on paper (prescribing) that would have been a very time consuming bit of logistics to sort that switch out. It was done within half a day…there are just some things where you know it just makes everything so much easier. (Medium 4)

On the other hand, it was noted that EPMA was more time consuming in other situations and could inhibit patient contact.

It's definitely more time consuming and people don't speak to patients as much because they can work remotely, those are the two negatives really. (Teaching 5)

The use of an EPMA system can result in new ‘workarounds’—ways that people discover to get the job done faster or easier, but are not officially documented in policies or procedures. People will, in effect, configure the EPMA system to meet their particular clinical workflow needs.3 It was also recognised that different professions work in different ways and the system needs to be configured to take account of this.

The problems we have (EPMA) tend to relate to the ingenuity of our staff in they have ways of working round (Large 3)

We need to think about how the medics would work, which is very different to the way we work. (Teaching 1)

Patient safety: safe and effective

Many interviewees mentioned that new error types had been encountered within EPMA, such as wrong selection of patient, drug and strength. Incorrect selection (from a dropdown menu) is an error unique to ePrescribing systems and cannot exist in paper systems as the prescriber does not select from a list, but rather writes his/her choice out. Some reported that human error was predictable in some cases, due to the design and layout of the EPMA system. The order in which the drugs appeared on the dropdown menu for selection was thought to have a bearing on whether the correct drug was selected. It was noted that HCPs tended to pick the drug at the top of the list because it is what they were expecting to see. Therefore, these errors had been minimised by changing the design of the system but human error had not been eliminated completely.

People kept picking the enteric-coated (aspirin) so when we put aspirin dispersible at the top of the list followed by enteric coated that sort of reduced that error almost completely. [It's] Funny people do tend to pick the thing at the top of the list because it's what they are expecting to see so it changes the nature of selection errors but it doesn't mean it removes them completely. (Teaching 2)

One chief pharmacist with paper prescribing in place acknowledged that the design of a safe and effective drug chart had gone as far as possible. Other interviewees felt prescribing had become of inferior quality over time due to changes in doctors' training.

It's [training] all about the diagnosis and the treatment is a poor second… I'm not saying it's not a consideration but the therapeutics is second to the diagnosis. (Medium 6)

During the telephone interviews, one chief pharmacist explained how the implementation of EPMA within the hospital had been a good quality initiative in itself. This initiative brought together representatives of all the professional groups that would be using the system and gaining their viewpoints, along with specific training. The chief pharmacist believed that if the same process was used when implementing a paper prescribing system, with the same ‘buy-in’, things might have been different regarding quality care or patient safety.

Discussion

The type of prescribing systems in place in acute trusts across England showed that out of the 65 interviews five different ePrescribing systems (JAC followed by MEDITECH, iSOFT, PICS and one in-house system) were in place in 12 trusts. The rest of the trusts had a paper drug chart on which to prescribe inpatient medications. Of the 12 trusts with ePrescribing in place, each system had different functionalities and supplementary paper prescription charts in use, this has also been revealed in previous research.20 Only nine trusts had not considered the publication relating to a standard prescription chart, three of which were trusts that had implemented EPMA.

Patient safety focuses on safeguarding patients in an effective manner. Illegibility is no longer an issue with EPMA systems.3 However, incorrect selection, such as the wrong selection of patient, drug, strength or frequency, could be classed as a comparable new error, and this was reported as a prominent issue among trusts using EPMA reinforcing previous research.12–18 During interviews, the order in which the drugs appeared on the dropdown menu for selection was thought to have a bearing on whether the correct drug was selected. It was noted that HCPs tended to pick the drug at the top of the list because it is what they were expecting to see.

Incomplete paper prescriptions, which could be considered a workaround, leads to issues of clarity and accuracy, which may be detrimental to quality patient care. The introduction of mandatory fields within the EPMA system has enabled ‘regulators’ to reinforce policies and guidelines, providing a significant benefit over the paper-based system. However, chief pharmacists in trusts with EPMA reported workarounds being evident in the working practices of their staff, where staff bypass the mandatory fields to streamline their working practices, which may lead to inaccurate information being supplied. If there is uncertainty about the information that is required, users of the system may be forced to guess or complete the mandatory field with misleading information.

Mandatory fields may be appropriate for core prescribing information, but the expansion of their use needs careful consideration. Taking into account the length of time mandatory fields may add to an HCP's clinical workflow, and the possible safety compromises resulting from workarounds. Despite this, many participants felt that being able to obtain full data sets giving detailed information on medicines use in a quick and efficient manner was an important advantage of EPMA systems compared with paper-based systems.

Forty-five per cent (65/146) of the chief pharmacists agreed to participate from across England. Therefore, the results do not reflect every hospital prescribing system across England. However, the recruitment technique did not rely on a convenience sample from conferences. Research into the implementation of EPMA systems in England is limited to convenience sample surveys during conferences19 and self-administered postal questionnaires.20 22 Typical response rates for research ascertaining the implementation of EPMA ranged from 32% to 61%. The European Hospital Survey Country Report for the UK states that 21% of 67 hospitals had ePrescribing in place.21

Several themes reinforced the need to seek opinions of all frontline HCPs about the different prescribing systems to understand how the social and technical aspects of prescribing systems interact and how changes to this might impact on quality of care.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the majority of inpatient prescribing in hospital continues to use paper-based systems. There was significant diversity in prescribing systems in use within the non-specialist acute setting, in January 2012, across England. However, an initial step towards standardising the design of prescription charts has been made, and the majority of interviewees reported having been consulted on the standards for the design of hospital inpatient charts. EPMA systems have been implemented but many trusts have retained supplementary paper drug charts, for a variety of medications.

Data indicated that the regulation required to provide quality patient care was perceived by some to be enforceable with an EPMA system, but that this may affect clinical workflow, leading to undocumented, unofficial workarounds that may be harmful. Mandatory fields may be appropriate for core prescribing information, but the expansion of their use needs careful consideration.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Implementation of electronic prescribing and medicines administration (EPMA) systems in hospitals across England has been slow, a situation that is also reflected internationally.

The NHS Commissioning Board set out a clear expectation that hospitals should make better use of information and technology by 2018.

What this study adds?

Among the respondents across England, only 18% of inpatient prescribing in hospitals used EPMA systems, with a significant diversity in prescribing system in use.

Regulation required to provide quality patient care was perceived to be enforceable with an EPMA system, but that this may affect clinical workflow, leading to undocumented, unofficial workarounds that may be harmful.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust and Liverpool John Moores University.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Liverpool John Moores University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. National Prescribing Centre. Improving quality in prescribing. 2012. http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20140627111521/http://www.npc.nhs.uk/improving_safety/improving_quality/

- 2. Goundrey-Smith S. Principles of electronic prescribing. London: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cornford T, Dean B, Savage I, et al. . Electronic prescribing in hospitals-challenges and lessons learned. Leeds: NHS Connecting for Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crooks J, Weir RD, Coull DC, et al. . Evaluation of a method of prescribing drugs in hospital, and a new method of recording their administration. Lancet 1967;1:668–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(67)92557-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gommans J, McIntosh P, Bee S, et al. . Improving the quality of written prescriptions in a general hospital: the influence of 10 years of serial audits and targeted interventions. Intern Med J 2008;38:243–8. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS FT. Adult in-patient medication prescription and administration record chart. Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS FT, 2011:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. University Hospitals of Leicester Adult Inpatient Medication Administration Record. 2011. (cited 1 March 2014). http://www.aomrc.org.uk/projects/standards-for-the-design-of-hospital-in-patient-prescription-charts.html

- 8. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Guy's and St Thomas’ NHS FT Inpatient Medication Administration Record. 2011. (cited 1 March 2014). http://www.aomrc.org.uk/projects/standards-for-the-design-of-hospital-in-patient-prescription-charts.html

- 9. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. The Leeds Teaching Hospitals Prescription Chart and Administration Record. 2011. (cited 1 March 2014). http://www.aomrc.org.uk/projects/standards-for-the-design-of-hospital-in-patient-prescription-charts.html

- 10. Winslow EH, Nestor VA, Davidoff SK, et al. . Legibility and completeness of physicians’ handwritten medication orders. Heart Lung 1997;26:158–64. 10.1016/S0147-9563(97)90076-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges in collaboration with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Royal College of Nursing. Standards for the design of hospital in-patient prescription charts London, 2011. http://www.rpharms.com/pressreleases/pr_show.asp?id=275 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slee A, Cousins D. Guidelines for hazard review of ePrescribing systems. Crown Copyright London, 2008. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130502102046/http://www.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/systemsandservices/eprescribing/hazard_framework.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savage I, Cornford T, Klecun E, et al. . Medication errors with electronic prescribing (eP): two views of the same picture. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:135 10.1186/1472-6963-10-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Donyai P, O'Grady K, Jacklin A, et al. . The effects of electronic prescribing on the quality of prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:230–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02995.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reckmann MH, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, et al. . Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:613–23. 10.1197/jamia.M3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tully MP, Ashcroft DM, Dornan T, et al. . The causes of and factors associated with prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2009;32:819–36. 10.2165/11316560-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. . Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 2005;293:1197–203. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, et al. . The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:415–23. 10.1197/jamia.M2373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cresswell K, Coleman J, Slee A, et al. . Correction: investigating and learning lessons from early experiences of implementing ePrescribing systems into NHS hospitals: a questionnaire study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:1–10. 10.1371/annotation/1cec200a-6652-449f-91e9-8effb769de1e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmed Z, McLeod MC, Barber N, et al. . The use and functionality of electronic prescribing systems in English acute NHS trusts: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e80378 10.1371/journal.pone.0080378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sabes-Figuera R. European Hospital Survey : Benchmarking Deployment of e-Health Services. Luxembourg, 2013. http://ftp.jrc.es/EURdoc/JRC85852.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Avery AJ, et al. . Planned implementations of ePrescribing systems in NHS hospitals in England: a questionnaire study. JRSM Short Rep 2010;1:33 10.1258/shorts.2010.010040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. TechUK. Digitising the NHS by 2018—one year on. London: TechUK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ash JS, Gorman PN, Seshadri V, et al. . Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:95–9. 10.1197/jamia.M1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.2012. NHS Choices. http://www.nhs.uk/Pages/HomePage.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2016-000905supp001.pdf (311.9KB, pdf)