Abstract

Background

Unexplained changes to medication are common at hospital discharge and underscore the need to standardise patient discharge clinical documentation. In 2013, the Health Information and Quality Authority in Ireland published a Standard on the structure and content of discharge summaries. The intention was to ensure that all necessary information was complete and communicated to the next care provider.

Objectives

This study investigated one Hospital's compliance with the Standard, and appraised two methods of electronic discharge communication (Symphony or Tallaght Education and Audit Management System (TEAMS)).

Method

A retrospective survey of 198 randomly selected discharge summaries was conducted at the study hospital, a 600 bed academic teaching hospital located in Dublin, Ireland.

Results

Of the 198 evaluated summaries, mean total compliance was 77%±4.2 (95% CI 76.3 to 77.5). Most (84.7%, n=173) summaries were completed using one of the systems (TEAMS). Absence of communication about alteration of preadmission medication was frequent (107 out of 130 patients (82.3%, CI 76.2 to 89.2)). Higher compliance rates were observed however, when information was interfaced or where there were dedicated fields to be completed.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve compliance with the National Standard for Patient Discharge Summary Information should focus on reporting changes made to medication during hospitalisation.

Keywords: Patient Safety, Medication Safety, Medication Error, Hospital Discharge, Discharge Communication, Care Transition, Medication Reconciliation

Introduction

Hospital discharge is an inherently risky transitional phase for patients because lapses in communication at the interface between secondary and primary care are common.1 As many as 50% of inpatients have been reported to experience a medication error as a result of inadequate medication reconciliation at discharge.2 Adverse events posthospitalisation affecting up to 20% of patients have been reported.3–5

It is therefore crucial for patient safety and efficient health provision after discharge that all information on the discharge summary is correct and complete.1 6 However, a systematic review by Kripalani et al7 found that discharge summaries often did not identify the responsible hospital physician (missing from a median of 25%), the main diagnosis (17.5%), physical findings (10.5%), diagnostic test results (38%), discharge medications (21%) and specific follow-up plans (14%). Transfer of discharge summary information is a multifactorial process and the relationships between the factors associated with these deficits and the quality of discharge communication are unclear.7 Factors which influence discharge summary information might be system related such as discharge summary template content, whether the discharge summary is handwritten or electronic, time available to communicate discharge information and whether the admission was planned or unplanned.7 Variations in the quality of discharge information may also be related to the individual such as the medical training of the person completing the discharge summary, the complexity of the patient’s care and discharge medication.8 Inherent limitations of audits that appraise the quality of discharge summaries, however, include their inability to control against external factors which can also affect discharge communication. Despite this, there are valuable lessons to be learnt regarding organisational and system level compliance.

Against the context of discrepancies at discharge there is now a national drive to ensure that patient clinical information is communicated effectively at transitions of care. The standardisation of discharge summaries has been advocated by different professionals and accrediting bodies internationally8–11 and the need for evidence-based recommendations for hospital discharge summaries in Ireland similar to those produced elsewhere was highlighted by Grimes et al.12 In Ireland, The Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) is the independent authority with statutory responsibility for setting standards for Health and Social services; and in 2013 published a National Standard for Patient Discharge Information, defining mandatory data fields to be communicated.13 Outpatients, long-term patient episodes or clinical specialties such as psychiatry are not considered within the remit of the Standard. Communication needs, the use of patient own drugs and the medication dosage form, are additionally required for discharge summaries in Northern Ireland and England.9 10

Information technology (IT) has a key role to play in the drive for continuous improvement in Irish healthcare. IT is conducive to more complete and accurate discharge summary communication.14 IT offers the potential to quickly extract information about diagnosis, medication and test results into a structured discharge document that can be augmented with the necessary details required under the National Standard. Such augmentation may facilitate semantic interoperability and easier integration of information to message recipients, for example, into general practitioner (GP) software systems.15 A recent systemic review by Mills et al16 explored the possibility of EU-wide standardised electronic discharge summaries, as interim electronic solutions are increasingly being adopted to generate inpatient discharge summaries; which in turn may facilitate cross-border electronic discharge communication.

The study site employs two electronic patient management systems both of which produce a discharge summary, Tallaght Education and Audit Management System (TEAMS) and Symphony. Both systems interface with the hospital's patient information management system for demographic content. TEAMS is an electronic health system (EHS) that enables discharge summaries to be generated electronically and sent to the patient's GP via Health Level 7 messaging. Clinical content is entered manually and is then automatically populated onto both the discharge summary and the prescription, as relevant, ensuring any details common to the two documents are identical; thereby reducing the risk of transcription error. Symphony is an EHS primarily used in the emergency and short stay units, for example, Acute Medical Admission Unit. Details are entered manually, and a discharge summary, but not a discharge prescription, can be generated. At the time of this study, Symphony discharge summaries were not electronically interfaced/messaged to GP systems.

The aim of this study was to audit randomly selected surgical and medical discharge documentation against HIQA's National Standard for Patient Discharge Summary Information. Selected elements within the dataset were chosen for the purpose of this study. This study also aimed to investigate compliance of each of the two systems with the National Standard, with a view to facilitating improvements to further enhance compliance.

Methodology

Study design and setting

A retrospective review of a sample of discharge summaries between September and October 2014 was conducted at one site. As a clinical audit, ethical approval was not required; however, appropriate authorisation to undertake the audit was previously obtained and covered this work. The study hospital is a 600 bed academic teaching hospital located in South West Dublin; dealing with 18 600 inpatient episodes a year and delivering general medical and surgical services. Approximately 2000 inpatient discharges occurred during the study period.

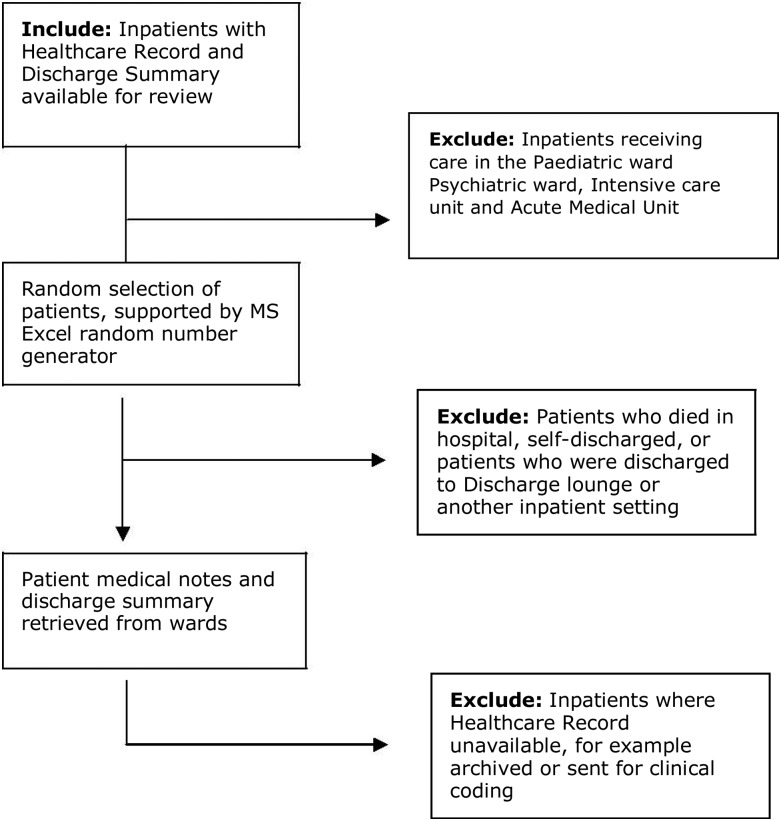

Sample selection

The sampling frame was adult patients discharged from medical and surgical wards. Patients discharged from paediatric, psychiatric and intensive care units were excluded. Daily lists of inpatient discharges were obtained from the hospital patient management system, and random selection was supported using random number generation in Microsoft Excel. The investigator undertook medication reconciliation based on the information available in the healthcare record and recorded by medical and pharmacy staff. The preadmission medication list was transcribed from the patient's admission note or clinical pharmacist's list and compared with the active discharge list on the Drug Prescription and Administration Chart and with the discharge summary with a view to identifying any discrepancies or differences.

A pragmatic approach to sample size calculation was employed based on the available investigator time. The main investigator was an undergraduate pharmacy student. A target of five patient discharge summaries per weekday over a 3-week data collection period was therefore set.

The relevant standards of the National Summary against which the audit would be carried out were identified. These were organised into three categories: ‘patient details and discharge information’, ‘medication information’ and ‘prescriber details’ (table 1). Allergy documentation was initially included in the study, but was subsequently excluded, as it was difficult to adjudicate from the sources of information available to the investigator.

Table 1.

Audit scoring criteria for Health Information and Quality Authority discharge summary components

| Patient details 1.1–1.6 | YES=correct patient demographic details communicated on discharge | NO=not present/incorrect |

| This is cross-checked with the patient's front chart extracted from the Patient Management System | ||

| Discharge destination address 1.7 | YES=correct destination address communicated on discharge. N/A=discharged home | NO=not present/incorrect |

| This is cross-checked with the last entry in the nurse's notes and patient medical notes | ||

| Date of discharge 3.6 | YES=date of discharge present and correct | NO=not present/incorrect |

| Date is cross-checked with the Patient Management System | ||

| Medication on discharge 5.1 | YES=all elements of patient medication fully communicated on discharge. NO=medication not fully communicated on discharge (any of the following not communicated correctly) | |

| ||

| Preadmission medications are cross-checked in the pharmacist admission note/TEAMS/non-pharmacist admission notes | ||

| New medication are cross-checked in the patient's drug chart | ||

| Particulars relating to the person(s) completing the discharge summary 7.1–7.5 | YES=forename, surname, contact number, job title and professional body registration number of person(s) completing discharge summary on discharge. NO=not present | |

| No check was made for accuracy | ||

| 7.11–7.12 | YES=discharging consultant's name and discharging speciality communicated on summary | NO=not present |

| Discharge speciality was cross-checked against the consultant speciality list | ||

*Where applicable.

The National Standard on which this study was based can be accessed online at: http://www.hiqa.ie/publications/national-standard-patient-discharge-summary-information (accessed 26 December 2015).

Data collection and outcome measures

A data collection tool was developed to record either ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘not applicable’ for the presence of each data item. Content and face validity of the data collection tool were further established through piloting. Randomly selected discharge summaries and completed data collection forms were reviewed by one of the authors, a clinical pharmacist, to assure consistency in data collection and inputting.

Although not exclusively the case, the majority of discharge summaries are completed by junior non-consultant hospital doctors, who typically rotate in July and January. Therefore, any effect related to staff turnover and affecting the external validity of this study was likely minimised during the data collection period.

Compliance was dichotomised; a binary ‘yes’/‘no’ response was used. The primary outcome was complete compliance with the selected elements of the National Standard. A discharge summary was deemed completely compliant if a ‘yes’ or ‘N/A’ was recorded for each of the selected criteria. A discharge summary total compliance score similar to that proposed by O'Leary et al17 was calculated by summing the number of elements that were rated as compliant (including non-applicable criteria) divided by the number of applicable elements for each discharge summary; multiplied by 100. The extent of compliance across the selected elements was reported as the secondary outcome.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (V.22). Descriptive analyses of audit characteristics were stated as means and SDs for normally distributed data or as medians and IQRs for parametric data; and as percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate analysis, specifically the Pearson χ2 test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate, was used to test for differences in compliance between the two discharge systems. The 2×2 contingency table technique for calculating ORs and their respective 95% CIs was used to estimate the strength of association between each criterion's compliance and the system. The accepted α level for all significance testing was 0.05. CIs of ORs that included 1.0 indicated statistical non-significance.

Results

Study sample

A total of 198 eligible discharge summaries were audited; with the majority (84.7%) completed using TEAMS. The study population was primarily older inpatients (median age 63 years, IQR=46–73). Discharge summaries completed on Symphony were same-day discharge, whereas TEAMS patients were discharged after a minimum 24 h stay. Just over half (50.3%) were male. The mean number of medication per patient at discharge, provided medication omissions were included, was 8.9±SD 5.8 (CI 8.1 to 9.7). Discharge summaries completed on TEAMS had a median of 9 medication prescribed at discharge (IQR=5–13), while Symphony discharges had a median of 4 (IQR=2–6.5). A minority of patients (4%) had no medication prescribed.

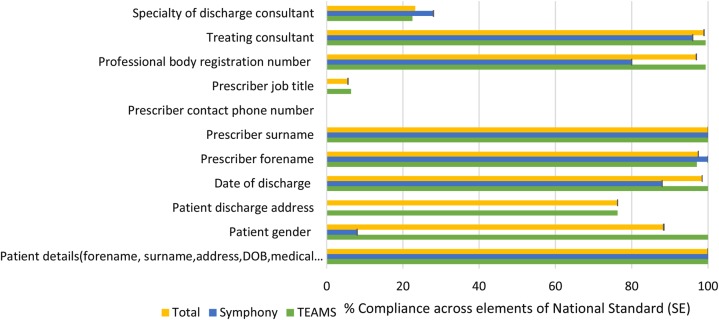

Compliance with HIQA requirements pertaining to patient demographic and discharge information

Compliance was observed in 100% of cases for most patient demographic information (name, date of birth and medical record number). For patient gender all TEAMS summaries versus 2/25 (8%) of Symphony summaries met the criteria for gender either implicitly denoted by Mr/Ms/Mrs or explicitly by referring to the patient as male or female. This was attributed to automation of gender information on the TEAMS system, but not on Symphony. The date of discharge on TEAMS was fully compliant as it is pulled automatically from the Patient information Management System (PiMS). The contact telephone number of the person(s) completing the summary was not recorded in any summaries evaluated. For 187 discharge summaries there was no indication of the medical training level of the doctor (intern, senior house officer (SHO), registrar, etc) completing the discharge summary. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the compliance with patient demographic and prescriber details across the two discharge systems.

Figure 1.

Study sample selection.

Figure 2.

Patient demographic and prescriber details, % compliance with National Standard with error bars representing the Standard error (SE). TEAMS, Tallaght Education and Audit Management System.

Compliance with HIQA requirements pertaining to medication information

The audit identified a total of 1683 medications prescribed at discharge, including 324 preadmission medication with no mention at discharge (19.3%, CI 17.5 to 21.1). Table 2 illustrates the compliance with medication-related elements per medication included on the discharge summary.

Table 2.

Compliance with medication details at medication level, treating omission as non-compliance

| TEAMS | Symphony | Total | 95% CI | χ2 | p Value | df | OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication level, excluding omission | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | |||||

| Generic drug name used | 1244/1272 (97.8) | 19/35 (54.3) | 1263/1307 (96.6) | (95.6 to 97.6) | – | 0.000† | 1 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.06) |

| Dose indicated | 1250/1272 (98.3) | 15/35 (42.9) | 1265/1307 (96.8) | (95.8 to 97.8) | – | 0.000† | 1 | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.03) |

| Frequency of administration indicated | 1254/1272 (98.6) | 12/35 (34.3) | 1266/1307 (96.9) | (95.9 to 97.9) | – | 0.000† | 1 | 0.01 (0.003 to 0.02) |

| Duration of therapy | 1106/1260 (87.8) | 11/35 (31.4) | 1117/1295 (86.3) | (84.2 to 88.1) | – | 0.000† | 1 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.13) |

| Changes on discharge | 84/90 (93.3) | 1/1 (100) | 85/91 (93.4) | (87.9 to 97.8) | – | – | – | – |

| Reason for change(s) to preadmission medication | 58/91 (63.7) | 1/1 (100) | 59/92 (64.1) | (54.3 to 73.9) | – | – | – | – |

| Indication(s) for medication newly started‡ | 246/478 (51.5) | 22/30 (73.3) | 268/508 (52.8) | (48.2 to 57.7) | 5.417 | 0.015 | 1 | 2.59 (1.13 to 5.94) |

*Likelihood of TEAMS compliance relative to Symphony compliance.

†Fisher’s exact reported as >20% of expected frequencies were <5.

‡Statistically significant.

TEAMS, Tallaght Education and Audit Management System.

Table 3 presents the extent of compliance with medication information per discharge summary for both systems. Medication omission was treated as non-compliant with the criterion ‘changes communicated on discharge summary’.

Table 3.

Compliance with medication details at patient level, treating omission as non-compliance

| TEAMS | Symphony | Total | 95% CI | χ2 | p Value | df | OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient level, including omission | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | |||||

| Generic drug name used† | 73/164 (44.5) | 3/25 (12) | 76/189 (40.2) | (33.9 to 47.1) | 9.538 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.17 (0.05 to 0.59) |

| Dose indicated† | 76/164 (46.3) | 3/25 (12) | 79/189 (41.8) | (34.9 to 48.7) | 10.516 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.55) |

| Frequency of administration indicated† | 76/164 (46.3) | 2/25 (8) | 78/189 (41.3) | (34.4 to 48.7) | 13.157 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.44) |

| Duration of therapy† | 64/164 (39) | 3/25 (12) | 67/189 (35.4) | (28.6 to 42.3) | 6.923 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.74) |

| Changes on discharge summary | 23/114 (20.2) | 0/16 (0) | 23/130 (17.7) | (10.8 to 24.6) | – | 0.074‡ | 1 | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.92) |

| Reason for change to preadmission medication | 24/47 (51.1) | 1/1 (100) | 25/48 (52.1) | (37.5 to 64.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Indication(s) for medication newly started† | 54/129 (41.9) | 12/16 (75) | 66/145 (45.5) | (37.2 to 53.8) | 6.304 | 0.012 | 1 | 4.17 (1.28 to 13.62) |

| Overall compliance with all medication criteria | 33/165 (20) | 3/25 (12) | 36/190 (18.9) | (13.7 to 25.2) | – | 0.432 | 1 | 0.55 (0.15 to 1.93) |

*Likelihood of TEAMS compliance relative to Symphony compliance.

†Statistically significant.

‡Fisher’s exact reported as >20% of expected frequencies were <5.

TEAMS, Tallaght Education and Audit Management System.

Statistically significant results between the two systems were observed for the duration of therapy, generic name, dose and indication for new medication (p<0.05). It appeared that TEAMS had higher compliance rates for communicating the generic name, dose, frequency on the discharge summary, whereas Symphony communicated the indication more often. Other comparisons were limited by the small sample size.

Compliance with HIQA requirements pertaining to therapy change information

The rate of alteration of preadmission medication at discharge without communication was high with 107 out of 130 patients (82.3%, CI 76.2 to 89.2) having discharge summaries with no documentation of changes (eg, dose/frequency) made to preadmission medication. This included omission of ongoing preadmission medication.

For those discharge summaries which involved a medication change, the reason for the change was present in around half (n=25, 52.1%). For new medications initiated during hospitalisation, the indication, either explicitly or implicitly inferred from recorded patient diagnostic information, was provided on 45.5% of discharge summaries (n=66).

Discharges compliant with all relevant criteria

Mean total percentage compliance for all relevant criteria on the discharge summaries was 77%±4.2 (95% CI 76.3 to 77.5).

Discussion

Overall compliance with HIQA's National Standard for Patient Discharge Summary Information was identified as 77%. However, compliance rates were identified as lower for medication details than for demographic or operator details. These findings corroborate with previous studies which cite medication details and rationale for therapy change as common omissions.13 18–21 Compared with discharge summaries completed using Symphony, TEAMS appeared to have a higher documentation rate for most of the audited data items.

Patient demographic details are automatically populated on TEAMS and Symphony from the hospital's PiMS, and this may account for the identified compliance rate of 100% for such criteria. However, for discharge summaries completed on Symphony there is no specific data field on the software program to input gender information and compliance rates were lower for this criterion. Similarly, free-format elements such as ‘indication for new medication’ had lower compliance rates concurring with a study by Callen et al21 which found a higher medication discrepancy rate with electronic transcription than with automated details. Standardising the format of the discharge summary template generated to incorporate this information may ensure more consistent completion.

One concern that was highlighted was the high proportion of changes to patient medication at discharge without complete information of them in the discharge summary. This accords with studies in the literature which document this problem.22 This is particularly significant as problems in reconciling the preadmission medication with the discharge medication list can lead to medication error which in turn may lead to preventable adverse drug events.23–25 Predictors of compliance found in other studies included quality of the discharge template, smaller numbers of prescribed medicines and use of electronic rather than handwritten discharge summaries.20 The sample size in this study was too small to compare TEAMS and Symphony compliance with this criterion. However, further work would be useful to investigate health informatics interventions to support medication reconciliation.

This study concurred with published evidence that medication omission is the most common discrepancy at discharge.13 16 17 Although it is plausible that the treatment was not continued on discharge according to good clinical judgement, the lack of explicit documentation poses a problem.26 These inconsistencies or gaps in documentation may be critical for the patient, as forgotten pharmacological therapy may entail inaccurate prophylaxis or treatment and provoke preventable adverse events. In fact, Perren et al26 found that 32% of medication omissions were potentially harmful. Furthermore, undocumented intentional changes to long-term medication during hospitalisation have been identified as carrying risk for medication error and adverse drug events.1

The most common medication initiated without indication in this study was painkillers, which are so ubiquitously used, a justification for their use seems almost unwarranted; which raises the question—which drugs merit an indication and where should the line be drawn? The reason for not providing an indication for newly prescribed medication at discharge may be because it is assumed that the GP might infer this from the patient's clinical history. However, this can increase the likelihood of adverse drug events and patient harm.26–28

Feedback on discharge summary completion could be used to support increased compliance by Symphony users or improvement in the system design, in particular on the need to include gender information. However, due cognizance should be given to the fact that the Symphony discharge system was primarily for same-day discharges, and the lack of detail reported could be explained given the time and resources required to report full medication lists. Medication reconciliation should be undertaken with a view to improving patient safety, and it is frequently reported to be time consuming.29 There are also likely differences in the level of medication burden and complexity between the two groups, and this must be taken into consideration.

The study conducted was a small, local evaluation of discharge summaries and consequently limits the external generalisability of the findings. As an observational study it is not possible to prove causality as other factors may influence the observed differences in compliance across the two systems. It is known that the causes of failure to reconcile medications are many and complex and this study took the opportunity to audit information management aspects only. In addition, the effects of observer bias and expectancy effects cannot be completely eliminated. The researcher's competence to undertake medication reconciliation as an undergraduate student is also questionable; although a proportion of discharge summaries and data collection forms were checked by the study supervisor.

There are no large-scale reports of the extent to which discharge summaries adhere to these standards and thus it is difficult to gauge their impact on the quality of practice. However, with the wider implementation of electronic discharge systems, this study has suggested that reviewing software design and in particular imputation rules may improve compliance rates. Communicating changes to the medication list should also be prioritised in discharge reconciliation.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject

There is a need for consistent and timely communication at discharge.

Poor communication at discharge increases the risk of adverse events and compromises the continuity of care.

Significant advances in technology have led to the development of more efficient electronic discharge communication systems. Computer-generated discharge summaries are legible, detailed and afford protection against transcription errors.

Recommendations on the minimum dataset for clinical discharge summaries to improve discharge communication have been stipulated in jurisdictions other than Ireland.

What this study adds

Previous research has focused on differences between handwritten and electronic discharging systems.

This study appraises the quality of medication-related information communicated at discharge using two different electronic discharge communication systems for compliance with the National Standard.

This study demonstrates that different electronic discharge systems and automation may impact on compliance with elements of the standard.

The existing literature mainly reports the quality of communication of the medication list at discharge. This study assesses patient, discharge and medication-related documentation against the National Standard.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:1373–9. 10.1345/aph.1L190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, et al. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2007;2:314–23. 10.1002/jhm.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, et al. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from inpatient to outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:646–51. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20722.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, et al. Post hospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1842–7. 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrero-Herrero JI, Garcia-Aparicio J. Medication discrepancies at discharge from an internal medicine service. Eur J Intern med 2011;22:43–8. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Philips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians, implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007;297:831–41. 10.1001/jama.297.8.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guideline and Audit Implementation Network. Guidelines on Regional Immediate Discharge Documentation for patients being Discharged from Secondary into Primary care. 2012. http://www.gain-ni.org/Publications/Guidelines/Immediate-Discharge-secondary-into-primary.pdf (accessed 26 Dec 2015).

- 9.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 128 Discharge Document. 2012. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/128/index.html (accessed 26 Dec 2015).

- 10.Health and Social Care Information Centre, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Standards for the clinical structure and content of patient records. London: HSCIC, 2013. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/healthcare-record-standards (accessed 26 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kind AJH, Smith MA. Documentation of mandated discharge summary components in transitions from acute to subacute care. Adv Patient Saf 2012;2:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimes T, Delaney T, Duggan C, et al. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharges: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir J Med Sci 2008;177:93–7. 10.1007/s11845-008-0142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Information and Quality Authority. National Standard for Patient Discharge Summary Information, 2013. http://www.hiqa.ie/publications/national-standard- patient-discharge-summary-information (accessed 26 Dec 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Motamdei SM, Posadas-Calleja J, Straus S, et al. The efficacy of computer-enabled discharge communication interventions: a systemic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:403–15. 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes TC, Duggan CA, Delaney TP, et al. Medication details documented on hospital discharge: cross sectional observational study of factors associated with medication reconciliation. Brit J Clin. Pharm 2010;71:449–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03834.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills RP, Weidmann AE, Stewart D. Hospital discharge information communication and prescribing errors: a narrative literature overview. EJHP 2015;23:3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Fienglass J, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in Quality and Timeliness using an electronic discharge Summary. J Hosp Med 2009;4:219–25. 10.1002/jhm.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwitz LI, Jengq GY, Brewster UC, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical centre. J Hosp Med 2011;8:436–43. 10.1002/jhm.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson S, Ruscoe W, Chapman M, et al. General practitioner-hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries. J Qual Clin Pract 2001;21:104–8. 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammad EA, Wright DJ, Walton C, et al. Adherence to UK national guidance for discharge information: an audit in primary care. Brit J Clin Pharm 2014;78:1453–64. 10.1111/bcp.12463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callen J, McIntosh J, Li J. Accuracy of medication documentation in hospital discharge summaries: a retrospective analysis of medication transcription errors in manual and electronic discharge summaries. Int J Med inform 2010;79:58–64. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unroe KT, Pfeiffenberger T, Riegelhaupt S, et al. Inpatient medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a retrospective Cohort Study of Age and Other Risk Factors for Medication Discrepancies. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:115–26. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, et al. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:1373–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lisby M, Nielsen LP, Mainz J. Errors in the medication process: frequency, type, and potential clinical consequences. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:15–22. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Doormaal JE, van den Bemt PMLA, Mol PGM, et al. Medication errors: the impact of prescribing and transcribing errors on preventable harm in hospitalised patients. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:227 10.1136/qshc.2007.023812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perren A, Previsdomini M, Cerutti B, et al. Omitted and unjustified medications in the discharge summary. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:205–8. 10.1136/qshc.2007.024588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes E, Hegarty P, Mahon A. Improving medication reconciliation on the surgical wards of a district general hospital. BMJ Qual Improv Reports 2012;1:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inge RF, van de Lar BV, Driseen E, et al. Analysis of medication information exchange at discharge from a Dutch hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:524–8. 10.1007/s11096-012-9639-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Greene J, et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med 2010;5:477–85. 10.1002/jhm.849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]