Abstract

Objective

For many patients with chronic conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the assistance of family carers with medicines is vital for optimal treatment outcomes. The aim of this study was to identify the assistance carers provide to patients with COPD using nebuliser-delivered therapy at home, and the problems experienced that may impact on the safety and effectiveness of therapy and contribute to carer burden.

Methods

A cross-sectional, qualitative descriptive study was conducted with participants recruited from primary and intermediate care. Home interviews were conducted with 14 carers who assisted a family member with COPD using a nebuliser. Qualitative procedures enabled analysis of nebuliser-related activities and problems experienced by carers.

Results

The carer sample included 10 female and 4 male carers, with a mean age of 61 years: 11 spouses and 3 daughters. They had assisted patients with use of their nebuliser and associated medications for, on average, 4.5 years. Assistance ranged from taking full responsibility for nebuliser use to providing help with particular aspects only when required. Nebuliser-related activities included assembling and setting up equipment, mixing medicines, operating the device, dismantling and cleaning equipment. Difficulties were described with all aspects of care. Carers reported concerns about medication side effects and the lack of information provided.

Conclusions

The study revealed the vital role of carers in enabling effective therapy. The wide-ranging responsibilities assumed by carers and problems experienced relate to all aspects of COPD management with nebulisers, and have a potential impact on treatment outcomes and carer burden. A systematic approach to addressing carers’ needs and prioritising support would be anticipated to have positive consequences for patients, carers and health services.

Keywords: COPD, nebulisers, family caregivers, medicines optimisation, pharmaceutical care

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may be prescribed domiciliary nebuliser therapy as part of a disease management plan.1 2 Nebulisers are used to deliver drugs with large therapeutics doses, for example, antibiotics, or for patients, such as the elderly and infirm, who have difficulties with handheld inhalers, where inhaling drug from a nebuliser using normal tidal breathing is advantageous. Effective use of medicines (especially inhalation therapy) is essential for successful disease management of patients with COPD. Exacerbations of disease and/or treatment failures may result in hospitalisation and constitute a significant burden to both patients and health services.

Nebulisers are complex to use, requiring assembly of equipment, dosing, frequently mixing with diluents, inhalation over several minutes, then dismantling, washing, sanitising and drying the equipment.3 Patients with COPD have physical and functional limitations, and often depend on help from family members who provide vital care.4–9 Reasons for reliance on carers include breathlessness, coexisting disabilities, visual impairment and arthritis.4

Medicine-related activities are an integral part of caring, and many patients with long-term illness depend on a family carer for assistance with use of medicines.10–13 Carers’ roles can include monitoring and maintaining medication supplies, assisting with drug administration, reminding and advising on doses and frequency, monitoring and advising on side effects, and sourcing information.11 12 Their level of involvement ranges from assisting with a small (but often significant) number of activities to taking full responsibility for all aspects of medication.12 Although a few studies have examined the impact on family carers of caring for someone with COPD, these have not examined medicine-related aspects.6 9 14–16 However, there is some evidence from the USA that assistance from a carer may be associated with improved medication adherence in patients with COPD.17 A recent review highlighted the paucity of information on the needs of family carers for people with COPD.8

The important contribution of family carers to healthcare is widely accepted, and support for carers has been identified as a policy priority.18–20 The Royal College of General Practitioners emphasises the importance of drawing on carers’ experiences in informing service development.21

For these patients, achieving optimal therapeutic outcomes to prevent hospitalisation will depend on effective nebuliser use. Currently, little is known about the assistance family carers provide to patients with COPD who are using nebuliser therapy, and the specific problems they experience. The aim of this study is to identify the roles and perspectives of carers assisting such patients, and to inform strategies that will enable healthcare professionals to support carers in their roles, reduce carer burden and optimise health outcomes.

Methods

This was a descriptive study employing qualitative methods. Data were collected in semistructured interviews in carers’ homes. Participants were identified from two settings: one primary-care setting comprising 38 general practitioner (GP) surgeries and one intermediate-care setting (healthcare and rehabilitation team located at a major acute hospital). Together, these settings enabled involvement of carers of patients whose disease management may be stable in the community, and carers who assisted patients recently admitted to hospital with an exacerbation, possibly indicating treatment failure. All patients eligible to participate in the study were identified by collaborators at the study sites. Patients with a confirmed COPD diagnosis, prescribed Nebules/Respules and/or Combivent (ipratropium and salbutamol) for use with a nebuliser in their home were identified. Patients with mental health problems, severe cognitive impairment, were unwell or had a serious illness (eg, advanced cancer) were excluded from the study. An invitation pack was forwarded to all patients who were asked to identify any relative or a friend from whom they received assistance with their nebuliser. This pack also included an information leaflet and reply slip for carers. Home interviews were arranged with carers who returned a reply slip indicating their willingness to participate. An analysis of patients’ practices and experiences of nebulisers was also undertaken and has been reported separately.3

The semistructured interview schedule comprised structured and open questions. Structured questions were used to identify the range and extent of assistance provided by carers with nebuliser use. Open questions enabled detailed discussion of carers’ experiences and difficulties regarding all aspects of their assistance and actions taken to resolve problems. The interview schedule gathered details about the assistance provided with respect to decisions regarding the need for therapy, setting up and operating the nebuliser, cleaning, maintenance and maintaining supplies, liaison with healthcare providers and suppliers and information sources. The researcher was a PhD student with a pharmacy background and training in qualitative methods. Her expertise in therapeutic and technical aspects of nebuliser use enabled the identification and examination of all aspects from the perspectives of the carers. Informed consent was obtained with the researcher prior to the commencement of each interview. All interviews were recorded and data transcribed verbatim. The Framework approach was employed in the analysis.22 This matrix-based analytical method enables a systematic approach to data analysis, while allowing application of qualitative procedures. Initial themes were guided by the domains of the interview schedule to include all aspects of nebuliser use. Qualitative procedures (constant comparison) were applied within this framework to ensure that findings were a true reflection of carers’ practices, experiences and perspectives in all domains.

Data analysis was facilitated by use of the FRAMEWORK software developed by NatCen specifically to support the framework method. Ethics approval was obtained prior to commencement of the study.

Results

Response rate and characteristics of the carers

One hundred and eighty patients were sent invitation packs; 83 returned the reply slip and 60 agreed to participate. Fifteen respondents reported that they were assisted by a family carer, 14 of whom agreed to take part and were interviewed. The carer sample included 10 female and 4 male carers, with a mean age of 61 years (range 26–79). Eleven were spouses and three daughters, all living with the patient. On average, the carers reported that they had assisted with nebuliser therapy for about 4.5 years and spent approximately 3.5 h per week (range 1–10.5 h) on nebuliser-related activities. They provided assistance with a mean of six different nebuliser-related activities (range 2–9) and reported encountering an average of three difficulties (range 0–9) while providing this assistance (table 1).

Table 1.

The number of family carers assisting, and reporting difficulty, with each activity (n=14)

| Activity | No. of carers performing activity | No. of carers reporting difficulty |

|---|---|---|

| Making decisions on the need to use the nebuliser | 8 | 4 |

| Supervising the nebulisation process | 9 | 4 |

| Setting up and operating the nebuliser | 12 | 8 |

| Assisting with inhaling the nebulised medication | 3 | 1 |

| Dismantling and cleaning the nebuliser | 10 | 7 |

| Maintaining supplies of disposables (eg, tubing) and condition of the nebuliser | 9 | 6 |

| Maintaining supply of nebulised medication | 11 | 4 |

| Making decisions to seek help in an emergency | 8 | 3 |

| Monitoring side effects of nebulised medication | 11 | 3 |

| Gathering information on the use or safety of nebuliser | 8 | 2 |

The results are described under three main themes: assistance in decisions regarding the need for therapy including advice on doses and the need for emergency help; setting up and operating the nebuliser including cleaning, maintenance and obtaining supplies; and obtaining information.

Assistance in decisions regarding the need for therapy

Decisions regarding nebuliser therapy included the need to initiate the therapy (n=6), adjusting doses (n=1), withholding a dose (n=1), or giving advice on discontinuation of therapy (n=1). Advice to use therapy was in response to noticing or hearing their relative experiencing breathing difficulties, or as a precautionary measure prior to an anticipated increase in the patient's physical activity, which might trigger breathlessness. Carers expressed concerns with regard to knowing when to initiate therapy and the frequency of dosage:

We didn't want to have it (nebuliser therapy) because… he puts on a lot of weight, he fills with water, but he said—don't worry, it's better to start it straight away than to wait. We used to wait until he couldn't breathe at all, you see?

Female, 74 yrs old, assisting for 4 yrs

Concerns were raised by carers about safety, the patient developing tolerance and side effects of nebulised medication. Differing perspectives of carers and patients about the need for medication were sometimes revealed.

Some days he looks like he's got the shakes for that is the Ventolin® anyway, because that does make you shake because I've been on that myself in the past and yeah…that wears off doesn't it after a while, but he does, I just leave him to sit quiet, I watch him, he doesn't always know that I'm watching him.

Female, 66 yrs old, assisting for 5 yrs

Well, when she's bad she'll use it [the nebuliser] up to four times a day; when she's good maybe only once or twice. So she tries not to use it, she's stubborn; she tries her hardest not to use it.

Female, 26 yrs old, assisting for 5 yrs

Carers reported contacting a doctor or calling for an ambulance when nebulised therapy failed to relieve the patient's breathlessness. However, difficulties in recognising the symptoms of an exacerbation and distinguishing them from other symptoms related to age or underlying conditions were experienced. Unclear information received from healthcare professionals further complicated this task:

…the receptionist said to me “do her lips go blue?” Well her lips don't always go blue. At one point they ask me is her lips blue…, and I said “no” and then we got an emergency doctor in; he took her oxygen levels and said “oh my god she's got to go to a hospital immediately, they're so low”, and I said “blue lips is not an indication necessarily because she lives on low oxygen levels anyway”…

Female, 60 yrs old, assisting for 10 yrs

Setting up and operating the nebuliser

The compressor, used to generate an aerosol from fluid placed in the nebuliser chamber can be noisy in operation. To overcome this, one carer described how her mother covered the nebuliser with a duvet to silence it during night-time use. The weight of the compressor could be problematic, for example, necessitating the use of a trolley on excursions. Being unable to use the nebuliser in the event of a power cut, as the nebuliser required mains electricity was also of concern.

Carers described assisting with connecting tubing between the nebuliser chamber and compressor, pouring drug fluid into the medication reservoir, screwing the cap back on the chamber, and connecting the facemask or mouthpiece to the device before giving the nebuliser to the patient to start inhaling the nebulised dose:

He can't put the solutions in when things are bad. He doesn't understand which ones to put in. He couldn't tell the difference between the two; the antibiotic and the other one. So he does need somebody to make sure he is doing it properly.

Female, 64 yrs old, assisting for 3 yrs

Some carers reported technical difficulties; especially related to overstretched tubing, but also to the lengthy process of setting up and operating nebulisers when medication was needed immediately and uncertainty regarding dilution of the medication (usually with physiological saline):

Sometimes this [tubing] does come off. It sort of blows off you know and we have to keep pushing it back on and that doesn't stay in there too well.

Female, 67 yrs old, assisting for 4 yrs

…that's the bit that we're not sure about because sometimes he uses distilled water, sometimes he doesn't put any water in and I don't know if that's right.

Female, 29 yrs old, assisting for 10 yrs

During nebulisation, carers may assist in fitting the mask to the patient's face and advising on his/her breathing pattern, sometimes being concerned whether full effectiveness was achieved:

I have to say I don’t think he does enough deep breathing….I say come on breathe in and breathe out.

Female, 75 yrs old, assisting for 0.5 yrs

Dismantling and cleaning

Dismantling the nebuliser system after use and subsequent cleaning is essential. Carers described washing nebuliser parts with warm soapy water, wiping the compressor and disinfecting parts with commercial detergent. Some reported that these tasks may not be undertaken when they were unavailable. Difficulties in dismantling the device were reported, resulting from poor manual dexterity due to arthritis, poor maintenance or understanding of the nebuliser parts. In two cases, carers described incidents where the tubing was stuck and could not be detached from the nebuliser. Two others expressed concerns over blocked tubing which could not be cleaned properly.

Maintenance, servicing and obtaining parts

Carers invariably took responsibility for purchasing or obtaining disposable components (nebuliser, facemask, mouthpiece, tubing), booking and taking the nebuliser for servicing or repair. They reported difficulties in accessing disposable parts through the hospital or local surgery, and revealed health professionals were uncertain about whether (or under what circumstances) different items could be provided. Other concerns included: non-availability of nebuliser services, lengthy procedures for obtaining a nebuliser, lack of information on maintenance and fears of being without a nebuliser if equipment failed. When relying on private suppliers, the costs, practicalities of trips to manufacturers and their agents, and problems obtaining required items and quantities were raised:

We bought packages from the company and you get loads of stuff you don't need. You know you couldn't buy the tubes without [the nebuliser], you know on their own, and that kind of thing; you're like paying £20 for a package with loads of stuff you don't use.

Female, 60 yrs old, assisting for 10 yrs

Carers were commonly responsible for ordering and collecting supplies of nebuliser medication from doctors’ surgeries and pharmacies.

Obtaining information

Carers drew on a variety of information sources: GPs, manufacturers’ instruction manuals, medication leaflets and family members with medical backgrounds. A range of information needs were outlined: frequency of dosage, required volume of nebuliser fluid, adverse effects, nebuliser cleaning and maintenance, and actions to be taken in case of treatment failure or equipment breakdown. The use of several inhaler devices (nebuliser users frequently also use handheld inhalers) was a source of confusion for some carers. Inconsistent information and lack of understanding of changes to prescriptions or regimens also caused problems:

My husband is on three different inhalers, so we weren't entirely sure how they really work…He was told to take them, but we weren't really sure what we were supposed to be doing.

Female, 67 yrs old, assisting for 4 yrs

The responsibility for managing medication, with limited knowledge and understanding could be stressful:

I'm not a doctor and I'm not a nurse and they mustn't view me as that…they can do this, but at the end of the day […] if something bad happened to her, I would say “is that me?’ ‘Did I do that?”

Female, 60 yrs old, assisting for 10 yrs

Discussion

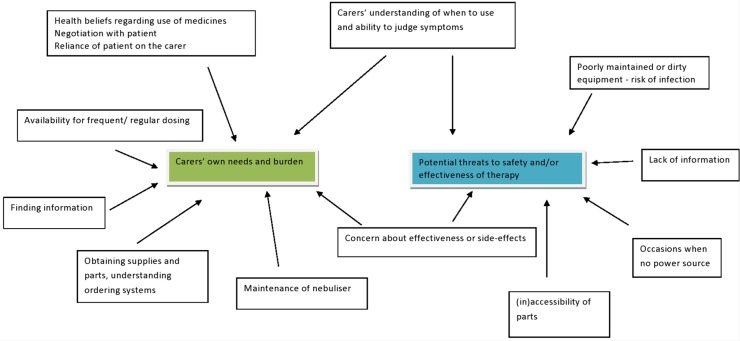

Figure 1 illustrates the study findings, indicating the potential impact on patients’ medicine-related outcomes and carer burden.

Figure 1.

Family carers who assist patients with COPD with nebulisers: potential impact on treatment outcomes and carer burden.

The responsibilities assumed by carers and the problems and concerns experienced varied hugely, and apply to all aspects of nebuliser use.

Previous research has acknowledged that older people with COPD depend on a carer for assistance, potentially resulting in considerable carer burden.8 9 14–16 23 24 However, in these studies there has been little focus on assistance with medicines, which is vital for treatment outcomes, yet contributes to carer burden.25 One such study did identify, from patients’ and carers’ perspectives, that nebulisers conferred benefits that outweighed their disadvantages especially when compared with other inhalation devices, but did not discuss nebuliser-related support and problems.26 The present study details the extent of support and range of activities with nebulisers for which carers assumed responsibility. This included practical assistance specific to nebuliser use and maintenance, organisational and therapeutic roles, such as obtaining and administering medication, making clinical judgments on the need for medication and in response to side effects, and seeking information from a range of sources.

Respondents indicated several concerns which should be addressed to permit them to ensure optimal nebuliser use. Currently, while nebuliser medication is allowed to be prescribed in the UK on the NHS, equipment, including compressors, nebulisers, facemasks, mouthpieces and connecting tubing are not. Hence, the sources and use of equipment are not standardised, with patients receiving equipment from GP surgeries, local hospitals, charities or purchasing it themselves. This presents problems for patients and their carers who are themselves frequently elderly. The carers commented on the difficulties with obtaining equipment, the associated costs, problems of getting equipment (constantly used) serviced and the cost of ‘disposable’ items that came packaged with unneeded sundries.

Some concern was expressed regarding poor portability of nebuliser equipment and the constant need for a power supply. Portable nebulisers with rechargeable battery packs are commercially available. Such devices should be made available, where appropriate, to this patient group.

Nebuliser equipment including the nebuliser chamber, tubing and mouthpiece requires regular washing and disinfection, according to manufacturers’ recommendations. Even in this small sample problems associated with cleaning were evident, either due to the practicalities of dismantling and cleaning the equipment or, as this activity was frequently undertaken by carers, it was not done in their absence. Nebuliser medications are unpreserved and inadequate cleaning and decontamination may lead to microbial colonisation of equipment, posing an infection risk to the patient,27 28 potentially leading to hospitalisation.

In addition to nebuliser-specific activities and problems, the carers expressed concerns about overdosing, difficulties in determining the correct dose, care-recipient's reluctance to use medication, perceived need for more information from healthcare professionals, worries about disruption in medication supply, the complexities of obtaining disposable parts and nebuliser maintenance, and the level of vigilance required to monitor the care-recipient's condition. All have potential implications for optimal medicines use, adherence to dosing regimens and therapeutic outcomes. These concerns also contribute to carer burden.25

Strengths and limitations of this study

Carers were recruited through primary and intermediate care, permitting involvement of carers of a diverse patient group. Interviews were conducted in the patient's homes, enabling a detailed examination and discussion of nebuliser-related activities. There are several limitations: the sample was confined to 15 people who identified themselves as carers. It is possible others, who perceive they provide only limited assistance (which could be vital to patient care) did not consider themselves eligible, and were therefore excluded. Carers from residential homes or other community day care services who have responsibility for patients, and who may face different challenges were not included. It is also possible that carers experiencing the highest levels of burden were not well represented in this study, being reluctant to participate due to time constraints.

Implications for policy, practice and future research

The UK Government recognises the important role of family carers and their contribution to healthcare, potentially enabling older people to remain in their own homes for longer,18 a desire shared by patients and important to carers. Support for family carers has been identified by the UK Department of Health, as a policy priority.18–20 A system of support that specifically includes carers and addresses their needs and difficulties should be a priority for health professionals. The Royal College of General Practitioners acknowledges the importance of service developments for carers being informed by their views and experiences.21 This paper provides detail on needs and problems from the perspective of carers to inform future proposals. Suboptimal domiciliary use of nebulisers by patients with COPD is a potential source of treatment failure leading to hospitalisation. Thus, health professionals need to identify patients who rely on carers regarding the use of their nebulisers. They should ensure that interventions and consultations are arranged to enable the involvement of carers, so that their roles and needs can be addressed. Future research should focus on interventions to improve support for carers (especially when treatment commences and regimens are changed). Potential interventions should be evaluated first, in terms of their feasibility and acceptability to patients, carers and health professionals, and second, in terms of their impact in reducing carer burden and optimising disease management in the community.

Conclusion

Although the sample was small, the study demonstrated that the optimal use of nebulisers by patients with COPD is inextricably linked to the roles and responsibilities of family carers. A systematic approach to addressing the needs of carers is anticipated to have an impact on patients’ outcomes, health services and carer burden.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject

Effective management of COPD for many patients in their homes depends on the correct use of their nebuliser.

Many patients with chronic illness depend on a family carer for assistance with medicines.

Assistance provided by family carers is often vital for successful outcomes, but can lead to significant carer burden.

What this study adds

Family carers who provide vital assistance in the home for patients with COPD depending on a nebuliser can experience problems with all aspects of its management and use.

Responsibilities and problems experienced by carers in nebuliser-related activities will potentially impact on both treatment outcomes and carer burden.

A systematic approach to supporting family carers would have positive consequences for patients, carers and health services.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contribution of collaborators from Harrow Primary Care Trust: Mrs Uma Bhatt, Mrs Meena Sethi and Ms Zinat Rajan for help with conducting the study and facilitating data collection. We acknowledge the assistance of staff in all practices with the identification and recruitment of eligible participants, and thank all patients for their participation.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the planning, execution of the research and final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Public Authority for Applied Education and Training, Kuwait.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was granted ethical approval from Harrow Research Ethics Committee, REC reference 08/H0719/55.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study was small, but we are happy to be contacted regarding sharing of anonymised data.

References

- 1.British Thoracic Society. Current best practice for nebuliser treatment. British Thoracic Society Nebuliser Project Group. Thorax 1997;52(Suppl 2):S1–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London, UK: National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alhaddad B, Smith FJ, Robertson T, et al. . Patients’ practices and experiences of using nebuliser therapy in the management of COPD at home. BMJ Open Respir Res 2015;2:e000076 10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teale C, Jones A, Patterson CJ, et al. . Community survey of home nebulizer technique by elderly people. Age Ageing 1995;24:276–7. 10.1093/ageing/24.4.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barta SK, Crawford A, Roberts CM. Survey of patients’ views of domiciliary nebuliser treatment for chronic lung disease. Respir Med 2002;96:375–81. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langa KM, Fendrick M, Flaherty KR, et al. . Informal caregiving for chronic lung disease among older Americans. Chest 2002;122:2197–203. 10.1378/chest.122.6.2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto RA, Holanda MA, Medeiros MMC, et al. . Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2007;101:2402–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caress A-L, Luker KA, Chalmers KI, et al. . A review of the information and support needs of family carers of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:479–91. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02556.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson AC, Young J, Donahue M, et al. . A day at a time: caregiving on the edge in advanced COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010:5:141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein R, Rivers P. The medication role of informal carers. Health Soc Care Community 1996;4:150–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.1996.tb00059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis S, Bethea L. Medication administration by family members of dependent elders in shared care arrangements. J Clinical Geropsych 2001;7:231–43. 10.1023/A:1011395229262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis S, Smith F, Gray N, et al. . The roles of informal carers in the management of medication for older care-recipients. Int J Pharm Pract 2002;10:1–9. 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2002.tb00581.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis SA, Smith F, Gray N, et al. . Partnerships between older people and their carers in the management of medication. Int J Older People Nurs 2006;1:201–7. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2006.00032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sexton DL, Munro BH. Impact of a husband's chronic illness (COPD) on the spouse's life. Res Nurs Health 1985;8:83–90. 10.1002/nur.4770080115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergs D. “The Hidden Client”–women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2002;11:613–21. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanervisto M, Kaistila T, Paavilainen E. Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a family's everyday life in Finland: perceptions of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spouses. Nurs Health Sci 2007;9:40–7. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trivedi RB, Bryson CL, Udris E, et al. . The influence of informal caregivers on adherence in COPD patients. Ann Behav Med 2012;44:66–72. 10.1007/s12160-012-9355-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HM Government. Carers at the heart of 21st-century families and communities. London, UK: HM Government, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health. Caring about carers: a national strategy for carers. London, UK: Department of Health, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. Living well with dementia a national dementia strategy? London, UK: Department of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.RCGP. Commissioning for carers. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie J, Spencer L, O'Conner W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, eds. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 2003:219–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miravitlles M, Maria L, Longobado P, et al. . Caregivers’ burden in patients with COPD. Int J COPD 2015;10:347–56. 10.2147/COPD.S76091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakken N, Janssen DJA, van der Bogaart EHA, et al. . Informal caregivers of patients with COPD: home sweet home? Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:498–504. 10.1183/16000617.00010114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith F, Francis S-A, Gray N, et al. . A multi-centre survey among informal carers who manage medication for older care recipients: problems experienced and development of services. Health Soc Care Community 2003;11:138–45. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharafkhaneh A, Wolf RA, Goodnight S, et al. . Perceptions and attitudes toward the use of nebulised therapy for COPD: patient and caregiver perspectives. COPD 2013;10:482–92. 10.3109/15412555.2013.773302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wexler MR, Rhame FS, Blumenthall MN, et al. . Transmission of gram-negative bacilli to asthmatic children via home nebulizers. Ann Allergy 1991;66:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutchinson GR, Parker S, Pryor JA, et al. . Home-use nebulizers: a potential primary source of Burkholderia cepacia and other colistin-resistant, gram-negative bacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 1996;34:584–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]