Abstract

Background

Palliative care requires the collaborative efforts of an interdisciplinary team, and as such a range of health professionals should be involved in supporting patients with life-threatening diseases. As a part of this therapeutic network, pharmacists at residential hospices should be thoroughly involved in care, cooperate with other medical staff and perform pharmaceutical services in order to deliver safe and efficient pharmacotherapy.

Aim

To provide an overview of the current state of pharmacy practice at Polish residential hospices.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was applied and three types of anonymous questionnaires were developed to collect data. Hospice directors, pharmacists and physicians from all residential hospices in Poland were invited to participate.

Results

19 (61%) hospices collaborate with at least one pharmacist, who performs pharmaceutical services on the premises. 12 (75%) pharmacists provide advice concerning medicines and 11 (69%) are involved in various roles related to procurement, dispensing and storage of drugs, as well as creating procedures for these activities. Despite pharmacists’ great level of involvement in drug policy, most of them are not members of the therapeutic team and they do not participate in ward rounds. Furthermore, the provision of clinical pharmaceutical services forms a minority of Polish hospital pharmacy practice.

Conclusions

Although the role of a hospice-based pharmacist is focused on the provision of drugs, it should become more clinical, that is, more patient oriented. The data obtained should be used as a source of information for implementing potential changes to palliative care pharmacy.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, DRUG PROCUREMENT, DRUG STORAGE AND DISTRIBUTION, PHARMACY MANAGEMENT (PERSONNEL)

Introduction

Palliative care, as a total sum of the care provided to patients with life-threatening diseases, requires an interdisciplinary team approach, and as such a range of medical and non-medical professionals should be involved in delivering the best care to patients until the end of their life.1 2 The hospice-based pharmacist is responsible for the appropriate and safe usage of medications, and as pharmacotherapy is often used for pain relief and relieving other distressing symptoms in palliative patients, pharmacists should form an important part of the therapeutic team.3 4 The activities of a pharmacist are based on clinical, educational, administrative and supportive responsibilities, and thus the role they play in hospice and palliative care is multidimensional.5

The provision of pharmaceutical services makes up a proportion of the complex care administered to patients at residential hospices. The main services in Polish hospices are similar to those performed within hospitals as they are directly associated with the provision of drugs. These services include the stocking and dispensing medications, compounding non-commercially available drug formulations and strengths, as well as monitoring recalls, market withdrawals and safety alerts concerning drugs and other products. Other practices consist of the detection and resolving of drug-related problems, providing drug information, advising providers on appropriate medication use, in-service education, education of patients and their families, and the development of policies and procedures regarding drug storage and handling. Moreover, pharmacists provide advice on the cost of drugs and medicinal products, as well as provide pharmacoeconomic analyses. Pharmaceutical care, as essential clinical pharmacy service performed by hospice-based pharmacists, is directly associated with the care of patients. According to the newest definition that is representative for Europe and for countries outside Europe, “pharmaceutical care is the pharmacists’ contribution to the care of individuals in order to optimise medicines use and health outcomes”.6 Since patients in palliative care constitute a unique group, some services performed more commonly within residential hospices highlight a more complex level of pharmaceutical care. These include providing information on the suitability of administering drug formulations via a feeding tube, crushing medicines and mixing with soft food, providing access to special equipment such as nebulisers or intravenous infusion pumps, recommending appropriate routes of administration for drugs and their formulations for patients with difficulties in swallowing, compounding drug formulations adjusted to the needs of a particular patient (eg, gel with morphine). In Poland, there are no comprehensive studies that examine pharmacist contributions to inpatient palliative care. Both quantitative and qualitative research is needed to gain a full understanding of this issue. In 2011, a preliminary survey was conducted among pharmacists and hospice directors, whose results have become the basis for the present national research.7 This study showed that half of the examined hospices employ a pharmacist, who in most cases gives information about drugs and is responsible for drug procurement.

This paper is the first to thoroughly describe pharmacist involvement in end-of-life care offered to patients, based on the collected views of three groups of respondents: pharmacists, physicians and hospice directors.

The aim of the study was to provide an overview of the current framework, context and scope of pharmacist activities in Polish residential hospices, and perform a direct observation on the status of clinical pharmacy in Poland. We were also interested in physicians’ and hospice managers’ perceptions on pharmacy practice and pharmacist role at the hospice as well as physician–pharmacist collaboration in this care.

Methods

Design

The cross-sectional survey was carried out with the use of three types of questionnaires addressed to three different groups of participants.

Participants

Pharmacists, hospice directors and physicians working at each residential hospice in Poland were invited to take part in this study. The selection of hospices was based on and verified through a commonly accessible web database of the Health Care Units Register (accessed 2011). The total number of units was 93. The study was conducted in 2012; therefore, all the hospices that participated in the survey had been operating for at least 1 year.

Materials

The material for the study was the data gathered from the questionnaires. The majority of the questions were closed-ended with tick box categories, which enabled clarity and quick responses. In some questions, participants could choose several answers, while in others, only one. Several question items were open-ended, which allowed the respondents to write their own opinions.8 Questionnaire no. 1 was addressed to hospice directors or hospice representatives designated by the directors. It included 20 questions encompassing general information about the hospice and its cooperation with the pharmacists. Questionnaire no. 2 consisted of 22 questions and was directed to pharmacists. Its aim was to obtain data related to the participants’ characteristics, pharmaceutical services performed at a given hospice, pharmacists’ involvement in solving drug-related problems and decreasing costs of therapy. The last questionnaire (no. 3) was sent to physicians who can potentially benefit from pharmaceutical services. This questionnaire was the shortest one as it contained only 10 questions concerning the characteristics of the surveyed professionals and their attitudes towards the role of pharmacists within a hospice. Some questions were the same or similar in all three questionnaires, so as to allow the researchers to make a statistically relevant comparative analysis between answers given by each of the three groups of respondents.

Procedure

Each of the Polish residential hospice was invited to the study. The questionnaires were developed by the researches on the basis of pilot study, literature and their own experience.

All three questionnaires (one for each type of participant) were distributed by post to predominated hospices. The applied method was analysis of the responses obtained from a set of questionnaires directed to pharmacists, hospice managers and physicians. For the analysis, descriptive statistics and χ2 test were applied. The former describes the basic features of the examined population and the latter was the most appropriate tool for measuring the association between two categorical variables from the questionnaire study. All statistical analyses were calculated with the use of STATISTICA V.10 software (StatSoft, 2010).

Results

Thirty-two hospices responded to this survey (response rate 34%). Some packages were incomplete, that is, they did not include all three questionnaires. A total of 77 responses were received: 31 questionnaires from hospice directors, 16 filled by pharmacists and 30 by physicians. The background characteristics of respondents are presented in tables 1–3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the examined hospices according to hospice directors (n=31)

| Characteristics features of the hospice | No. of hospices | % of hospices |

|---|---|---|

| Number of years the hospice has been active | ||

| <3 | 4 | 13 |

| ≥3 <5 | 1 | 3 |

| >5 ≤10 | 5 | 16 |

| >10 ≤20 | 16 | 52 |

| >20 | 5 | 16 |

| Number of beds in the hospice | ||

| <10 | 3 | 10 |

| ≥10 ≤20 | 21 | 68 |

| >20 ≤30 | 4 | 13 |

| >30 | 3 | 10 |

| Provider of pharmaceutical services in the hospice | ||

| Hospital pharmacy in the hospice | 3 | 10 |

| Hospital pharmacy outside of hospice | 5 | 16 |

| Hospital pharmacy department* | 11 | 35 |

| Other unit | 3 | 10 |

| No specialised unit | 9 | 29 |

| Person responsible for drugs procurement, their storage and relevant documentation | ||

| Pharmacist | 12 | 39 |

| Physician | 14 | 45 |

| Nurse | 19 | 61 |

| Administrative worker | 1 | 3 |

| Hospice director | 2 | 6 |

| No response | 1 | 3 |

| Does the hospice cooperate with pharmacists? | ||

| Yes | 19 | 61 |

| No | 12 | 39 |

| Answers given by hospices that cooperate with pharmacists (n=19) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of years the hospice has cooperated with pharmacists | ||

| <3 | 8 | 42 |

| ≥3 <5 | 1 | 5 |

| >5 ≤10 | 3 | 16 |

| >10 ≤20 | 4 | 21 |

| >20 | 2 | 11 |

| No response | 1 | 5 |

| Number of pharmacists cooperating with the hospice | ||

| 1 | 13 | 68 |

| 2 | 4 | 21 |

| 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Preferred form of employing pharmacists | ||

| Paid work | 13 | 68 |

| Volunteering | 5 | 26 |

| No response | 1 | 5 |

*It is a unit similar to a hospital pharmacy; however, it cannot provide all pharmaceutical services.

Table 2.

Background characteristics of pharmacists (n=16)

| Characteristics of the pharmacists | No. of pharmacists | % of pharmacists |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 3 | 19 |

| ≥30 <40 | 1 | 6 |

| >40 ≤60 | 10 | 63 |

| >60 | 2 | 13 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 56 |

| Male | 6 | 38 |

| No response | 1 | 6 |

| Length of service at the hospice (years) | ||

| <1 | 8 | 50 |

| ≥1 ≤3 | 2 | 13 |

| >3 ≤10 | 3 | 19 |

| >10 | 3 | 19 |

| Employment status | ||

| Paid work | 11 | 69 |

| Unpaid work (volunteering) | 5 | 31 |

| Number of working days in a hospice per week | ||

| 1 | 2 | 13 |

| 2–3 | 6 | 38 |

| 4–5 | 6 | 38 |

| Other | 2 | 13 |

| Number of working hours in a hospice per week | ||

| <40 ≥20 | 3 | 19 |

| <20 ≥10 | 5 | 31 |

| <10 ≥5 | 4 | 25 |

| <5 | 2 | 13 |

| On demand | 1 | 6 |

| No response | 1 | 6 |

| Other work places | ||

| Community pharmacy | 9 | 56 |

| Hospital pharmacy | 2 | 13 |

| University | 0 | 0 |

| Pharmaceutical company | 1 | 6 |

| Other | 1 | 6 |

| Only hospice | 3 | 18 |

| No response | 1 | 6 |

| Pharmacist's direct superior | ||

| Director/manager of the hospice | 15 | 94 |

| Head of the ward | 1 | 6 |

| Head nurse | 1 | 6 |

Table 3.

Background characteristics of physicians (n=30)

| Characteristics of the physicians | No. of physicians | % of physicians |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥30 <40 | 2 | 7 |

| >40 ≤60 | 22 | 73 |

| >60 | 5 | 17 |

| No response | 1 | 3 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 18 | 60 |

| Male | 12 | 40 |

| No response | 1 | 6 |

| Number of years of hospice service | ||

| <1 | 1 | 3 |

| ≥1 ≤3 | 4 | 13 |

| >3 ≤10 | 11 | 37 |

| >10 | 14 | 47 |

Table 4 presents the types of pharmaceutical services and other tasks performed by pharmacists at residential hospices. Additionally, the table includes data concerning services that should be provided by pharmacists according to the opinions of hospice directors and physicians.

Table 4.

Pharmaceutical services and other tasks that are or should be performed by pharmacists

| Pharmaceutical services that are performed at the hospice | Pharmaceutical services provided by pharmacists in their own opinion (n=16) | Pharmaceutical services that should be provided by pharmacists according to hospice directors (n=31) | Pharmaceutical services that should be provided by pharmacists according to physicians (n=30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of pharmacists | % of pharmacists | No. of hospice directors | % of hospice directors | No. of physicians | % of physicians | |

| Dispensing of drugs and medical devices | 10 | 63 | 15 | 48 | 13 | 43 |

| Co-participation in tenders related to drug purchase | 5 | 31 | 15 | 48 | 16 | 53 |

| Co-participation in drugs and medical devices management | 11 | 69 | 22 | 71 | 21 | 70 |

| Setting procedures for dispensing drugs to hospice wards and patients | 11 | 69 | 20 | 65 | 16 | 53 |

| Giving advice about drugs and medical devices | 12 | 75 | 17 | 55 | 15 | 50 |

| Participation in rationalisation of the therapy | 9 | 56 | 14 | 45 | 21 | 70 |

| Monitoring adverse drug reactions | 8 | 50 | 14 | 45 | 12 | 40 |

| Participation in clinical trials that are held at the hospice | 1 | 6 | 7 | 23 | 10 | 33 |

| Training hospice staff and volunteers | 4 | 25 | 12 | 39 | 12 | 40 |

| Preparing sterile drug formulations | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 27 |

| Drug compounding | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16 | 12 | 40 |

| preparing enteral feeding solutions | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 23 |

| Preparing daily doses of drugs including cytostatics | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16 | 5 | 17 |

| Documenting drug and medical device donations | 9 | 56 | 13 | 42 | 16 | 53 |

| Organisation of drugs and medical devices procurement | 11 | 69 | 17 | 55 | 21 | 70 |

| Drug monitoring | 7 | 44 | 13 | 42 | 12 | 40 |

| Educating patients | 3 | 19 | 5 | 16 | 11 | 37 |

| Other | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16 | 3 | 10 |

Regarding services provided by pharmacists, there was no statistically significant difference between pharmacists’ own opinions on the matter and the expectations expressed by hospice directors (p>0.05). Statistical analysis indicates a significant difference between pharmacists’ and physicians’ opinions with respect to the following tasks: co-participation in clinical trials at the hospice (p=0.0253), preparing sterile drug formulations (p=0.01581), preparing enteral feeding solutions (p=0.02602) and compounding drugs (p=0.00169).

Among other activities, pharmacists listed keeping documentation of psychotropic drugs and opioids provision as a being a major role within the hospice. Ten (63%) pharmacists estimated their involvement in this service at a level of 100%, three (19%) at 50% and one (6%) at 25%.

As far as patient-oriented activities are concerned, 12 (75%) pharmacists were not involved in direct patient care and 5 (31%) took part in special meetings dedicated to problems associated with the treatment of hospice patients. Four (25%) respondents individually answered that they consulted members of the therapeutic team about prescribed therapies, and two (13%) gave patients advice about their therapy. No pharmacist responded that they participated in hospice ward rounds.

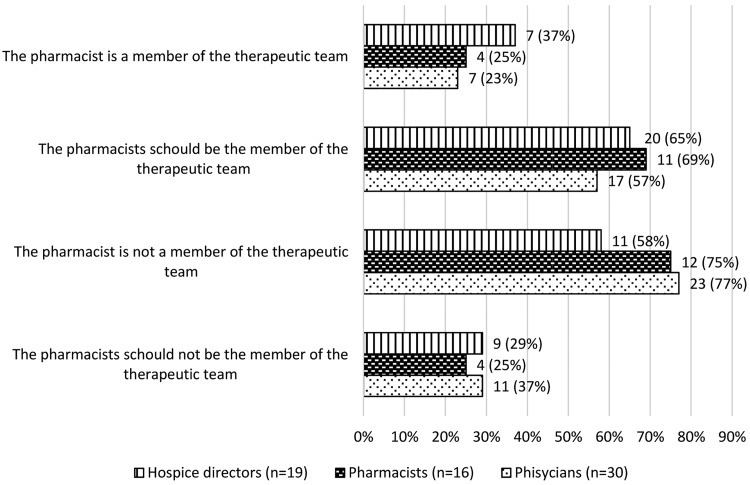

Most respondents answered that pharmacists were not considered members of the therapeutic team; however, they deemed that they should be. There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups (p>0.05). Detailed responses are presented in figure 1. According to pharmacists, the main reason for the inclusion of a pharmacist in a therapeutic team is to decrease the costs of therapy. Hospice directors attributed better drug management to pharmacist input and they also identified that pharmacists possess knowledge that can prove to be useful in the pharmacotherapeutic decision-making process. A small group of hospice directors were against the inclusion of pharmacists in therapeutic teams, arguing that the associated costs would be too high and that the tasks performed by the pharmacist were not helpful to the team.

Figure 1.

The pharmacist's relation to the therapeutic team.

Both hospice directors and physicians working at hospices cooperating with pharmacists indicated the necessity for including the pharmacist within the therapeutic team more frequently than respondents employed at hospices where there was no pharmacist contribution (p=0.02480 and 0.003, respectively). According to directors who manage units collaborating with pharmacists, within 16 out of 19 units (84%) pharmacists are found to advise members of the therapeutic team. Sixteen of the examined physicians (53%) have requested an opinion or advice from a pharmacist. They listed the following as topics of pharmacist consultations: new drugs, rationalisation and cost of pharmacotherapy, reimbursement, generic drugs, availability of drugs on the pharmaceutical market, drug interactions and compounding. Physicians reported that their interactions with pharmacists involved being advised on pharmacotherapy choices (8, 27%), monitoring adverse drug reactions (6, 20%), compounding (3, 10%) and others (clinical trials, ordering drugs, pharmacoeconomy). At 13 (43%) hospices, there was no pharmacist available, and a further four physicians stated that they had not cooperated with the pharmacist despite their employment at the hospice. In most cases, the pharmacist cooperated with the head nurse (16, 100%) and with the head of the ward (11, 69%). A smaller number of pharmacists collaborated with other nurses (9, 56%) and physicians (5, 31%).

Table 5 presents the benefits of employing pharmacists according to the opinions of hospice directors, pharmacists and physicians. There is no statistically significant difference between the opinions of each of the three groups of respondents regarding the benefits associated with providing pharmaceutical services at a hospice, with the exception of one advantage. The better selection of drugs for individual patients was indicated more often by hospice pharmacists than hospice directors (p=0.03) and physicians (p=0.02) as a valuable outcome of pharmacist input.

Table 5.

Benefits of employing pharmacists at residential hospices, according to hospice directors, pharmacists and physicians

| According to hospice directors (n=31) | According to pharmacists (n=16) | According to physicians (n=30) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits of employing pharmacists at residential hospices | No. of hospice directors | % of hospice directors | No. of pharmacists | % of pharmacists | No. of physicians | % of physicians |

| Better selection of drugs for individual patients | 9 | 29 | 11 | 69 | 8 | 27 |

| Monitoring adverse drug reactions | 12 | 39 | 10 | 63 | 8 | 27 |

| Improved access to drugs and medical devices | 16 | 52 | 11 | 69 | 14 | 47 |

| Proper drug storage | 19 | 61 | 13 | 81 | 15 | 50 |

| Introduction of new drugs and medical devices into the therapy/hospice practice | 13 | 42 | 6 | 38 | 8 | 27 |

| Decreased cost of pharmacotherapy | 17 | 55 | 11 | 69 | 16 | 53 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 10 |

| No response | 5 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 17 |

Discussion

All residential hospices in Poland were sought out as the targeted clinical settings of this study, and as such the collected data were perceived to be reliable as well as comprehensive due to the study being performed on a large scale. Additionally, the questionnaires directed to the pharmacists and hospice directors were pilot tested, which enabled the researchers to correct the questions and adjust them to each particular group of respondents.9 Therefore, the data were found to provide a satisfactory description of the activities performed by pharmacists within residential hospices in our country.

The pharmacist position in the hospice

The results indicate that pharmacists were not the first staff members approached for the procurement of medicines in the hospice. Hospice directors identified pharmacists as third in line, behind nurses and physicians. This highlights that in many Polish hospices this service was not provided in accordance with the law since the ordering of drugs does not fall within the authority of nurses and/or physicians. It was found that more than a third of Polish hospices did not collaborate with a pharmacist, which may be indicated as being the principal cause of such an unregulated practice. Furthermore, at the majority of the surveyed hospices, only one pharmacist was employed, and in most cases, they were engaged on a part-time basis. From these selected pharmacist perspectives, the hospice was an additional place of employment as they held concurrent positions in community pharmacies or other hospital pharmacies. Some of the examined pharmacists also identified themselves as volunteers. Despite pharmacist ages suggesting a significant level of working experience in a hospital pharmacy, the length of their hospice service was limited. This may be attributed to the short period of collaboration between Polish hospices and pharmacists, which has only recently been adopted within the last several years.

Pharmaceutical services performed at the hospice

When considering the pharmaceutical services offered within hospices, overall it was identified that Polish pharmacists were involved in providing information on drugs, ordering, dispensing and managing thereof, as well as the writing of guidelines for the usage of medicines at the hospice. In contrast to Polish pharmacists working at university hospitals, it was found that hospice-based pharmacists did not participate in drug compounding at all.10 However, an interesting finding from the responses of hospice directors and physicians highlighted that they expected pharmacists to prepare drugs within the dispensary. The latter staff group had much higher expectations than the former. These attitudes may arise from the perceived need for the provision of individualised therapy for patients as well as the need for the availability of specialised drug formulations, which may not be available commercially. As mentioned previously, most of the hospices had only a general hospital pharmacy department available to service their needs; therefore, it was not possible to perform drug compounding on the premises. It was revealed that pharmacists were deeply involved in administrative work, for example, maintaining documentation on the provision of opioids and psychotropic medications. This is a consequence of Polish legal regulations, which state that the pharmacist is responsible for performing these activities. Similarly, a study conducted in Canada and Australia showed that administrative duties and basic drug supply were very common in Australia; however, in contrast, Canadian pharmacists were more involved in teamwork and ward rounds.11

Clinical services

It can be assumed that, generally, patient-oriented activities were rarely performed within Polish hospices according to the level of participation displayed by pharmacists in clinical work. Pharmacists usually did not participate in direct patient care, and furthermore, unlike in other countries, not one responded to ever participating in ward rounds in their hospice practice experience. In Japan, 79% of surveyed pharmacists reported to attending ward rounds, and in Canada and Australia, pharmacists consider themselves to be important members of palliative care team.11 12 Another study demonstrated that in a geriatric hospital unit at least one drug-related problem was found in 75% of patients by a pharmacist who participated in ward rounds.13 However, from a positive perspective, individual pharmacists were identified through the course of the study as performing some clinical pharmacy services, including participation in specialised meetings dedicated to problems associated with patient care, educating other members of the therapeutic team about pharmacotherapy and advising patients about their treatment.

The pharmacist–therapeutic team collaboration

It can be undoubtedly acknowledged that teamwork comprises an integral part of end-of-life care and is beneficial both to patients and practitioners.14 According to a number of organisations, including The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, pharmacists play a pivotal role in the provision of hospice and palliative care. Therefore, the pharmacist, together with the physician, nurse, psychologist, physiotherapist, priest and volunteer, should be a member of a hospice interdisciplinary therapeutic team.4 The 2002 WHO definition of palliative care reaffirms this finding and classifies clinical pharmacists, physiotherapists and social workers as being part of an extended interdisciplinary team and further states that “all have an important contribution to make to the care of the dying”.15 The fundamental role of the pharmacist in hospice and palliative care is to maintain and optimise the quality of pharmacotherapy, whereas the decreasing of pain and other symptoms with the use of medications is one of the tasks of a therapeutic team.16 Although the vast majority of all respondents agree that pharmacists should be included in the palliative care therapeutic team, in Poland, the pharmacist is in reality almost never recognised as a team member at residential hospices, even though they are employed at the facility. Only a little more than a third of all hospice directors and about a quarter of all pharmacists and physicians treat the pharmacist as a therapeutic team member. Similarly, in Australia, the pharmacist is also not recognised as a member of the therapeutic team.17 On the other hand, other authors claim that in Australian hospice and palliative care units at hospitals clinical pharmacists are part of the interdisciplinary team and work that is in a contradiction to community pharmacy services, where a pharmacist does not have a close contact with healthcare proffessionals.18 in Japan, 70% of pharmacists collaborated with a palliative care team, with only 16% reporting that they did not contribute due to insufficient time (90%) and/or staff (68%).12 The current situation in Poland might be a result of either the lack of pharmacist numbers within hospice wards or their insufficient clinical role. Nevertheless, all respondents strongly agree to raise the pharmacists’ contribution to the therapeutic team that underlines the necessity for clinical pharmaceutical services. Additionally, physicians recognise the need for patient-oriented activities (giving advice, education of patients and staff, detection of adverse drug reactions and drug monitoring), which are performed by hospice pharmacists. Interestingly, the physicians and directors who cooperated with pharmacists were more enthusiastic about their inclusion into the therapeutic team than those who had no experience in working with pharmacists.

In regards to the relationships fostered between pharmacists and other staff members, in all cases the head nurse was found to be the main person with whom pharmacists cooperated. Almost 70% of pharmacists also collaborated with the head of the ward. In fewer cases, physicians and nurses who were on-call at the hospice collaborated with hospice-based pharmacists. These work patterns suggest that the collaboration between these professions relates to administrative and organisational duties, such as the procurement of medicines, rather than the addressing of clinical problems.

Educational role of the pharmacists

One of the most significant responsibilities of a clinical pharmacist involves the provision of advice on medicines. In the present study, the majority of the examined hospice representatives and only approximately half of the surveyed physicians emphasised the importance of the advisory role of the pharmacist within residential hospices. Most of the pharmacists (75%) identified that the provision of information and advice about drugs was one of the routine pharmaceutical services that they provided. Specialist literature highlights that pharmacists have a more active role in the education of physicians on medicines. For example, Wilson and her colleagues argued in their study that both patients and the medical staff could benefit from recommendations given by hospice pharmacists. They pointed out that 89.4% of clinical pharmacists’ recommendations in the context of palliative care were accepted by the physicians, which was associated with achieving the desired therapeutic goal.19 Another study also identified the positive impact of pharmacist advice on hospice patient care. The most important aspects were related to the rationalisation of inappropriate drug regimens, advising on interactions and therapeutic drug monitoring.20 Furthermore, Wilby and colleagues, who evaluated clinical pharmacy services in palliative care, reaffirm these findings and showed that discontinuing therapy, initiating therapy and providing education were the most common pharmaceutical interventions performed by pharmacists, encompassing a high acceptance rate of >80%.21

Benefits of pharmacist activities in a hospice

Most respondents agreed that the proper storage of drugs, decreased costs of the therapy, as well as improved access to drugs were major benefits of having pharmacist involvement in hospice and palliative care. The participants still do not acknowledge the clinical role of pharmacists. Less than 30% of hospice directors and physicians agreed that a pharmacist could aid in the better selection of drugs for individual patients; in contrast, the same opinion was expressed by as many as 70% of the surveyed pharmacists. Furthermore, a number of respondents pointed out that the presence of a pharmacist can decrease the costs associated with therapy.

Study limitations

There are some limitations of the study, and the results should be considered with caution. First, the response rate is not very high and it may be the cause of the potential bias. Nevertheless, all residential hospices were asked to participate in this study and their number in Poland is limited (93). Moreover, not all hospices employ a pharmacist, so the number of examined pharmacists is also limited. Second, the questionnaires were administered by post (not orally). Therefore, the respondents did not have chance to discuss the doubts related to the questions with the researchers. Finally, the survey did not examine opinions of other members of the therapeutic team (eg, nurses, psychologists) on pharmacists’ role and activities at hospice and palliative care.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the unique patient population seen in hospice and palliative care requires interdisciplinary level of care, including pharmaceutical services. The findings of this national study illustrate that pharmacist involvement in this type of care, in comparison to other countries, is unsatisfactory. It is particularly perceived at hospices that do not employ a pharmacist. Moreover, the clinical field of a hospice-based pharmacist's work is not highly developed. Polish pharmacists are not considered to be members of therapeutic teams nor do they provide patient-centred pharmaceutical care or participate in ward rounds. On the other hand, it is acknowledged that pharmacists are deeply involved in stocking and dispensing medications, as well as maintaining documentation on these activities. The study suggests that the respondents, including pharmacists themselves, do not identify pharmacists as being actively involved in direct patient care as the value of pharmaceutical services for hospice patients is severely underestimated. Nevertheless, the respondents would like this situation to change, which is a positive sign. All of them believe the pharmacist should be a member of the therapeutic team. Such attitudes may suggest that some modifications to Polish clinical pharmacy practice might be necessary.

Further research should concentrate on determining the types of changes that should be introduced into Polish hospices in order to improve pharmacist services. Additionally, it would be of interest to conduct a similar study in other countries based on the same questionnaire and determine and compare the activity of hospice pharmacists.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject

Pharmacists, together with other medical staff, support patients and their families in the hospice and palliative care.

The main pharmaceutical services provided by hospice-based pharmacists are similar to those performed within hospitals as they are both directly associated with the provision of drugs.

As patients in palliative care constitute a unique group, some pharmaceutical services are specific to these patients and they are performed more commonly within residential hospices.

What this study adds

The basic role of the pharmacist within Polish residential hospices involves the supply of medicines and drug management.

Most of the pharmacists surveyed are not members of the therapeutic team, and patient-oriented activities are not a common practice at Polish hospices.

Footnotes

Contributors: IP and LP designed the questionnaire and conceived the study. ML-N revised the questionnaire. LP collected and did statistical analysis of the data. IP wrote the first draft of this paper. LP and ML-N revised it critically and corrected it.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was anonymous and the objectives could not be identified. In an enclosed letter of intent containing information about the research, the participants were asked to take part in the study and fill the questionnaire.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en (accessed 12 May 2015).

- 2.De Conno F. Use of medicines in palliative care. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2012;19:28 10.1136/ejhpharm-2011-000064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radbruch L, Hoffmann-Menzel H, Kern M, et al. Cover story. Hospice pharmaceutical care: the care for the dying. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2012;19:45–8. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2011-000016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist's role in hospice and palliative care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59:1770–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker KA, Scarpaci L, McPherson ML. Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:511–13. 10.1177/1049909110371096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allemann SS, van Mil JW, Botermann L, et al. Pharmaceutical care: the PCNE definition 2013. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:544–55. 10.1007/s11096-014-9933-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawłowska I, Pawłowski L, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M. Rola i zadania farmaceuty w hospicjum stacjonarnym na podstawie badania pilotażowego. [Pharmacist's role and his activities in residential hospice on the basis on preliminary study]. Medycyna Paliatywna 2012;2:80–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boynton PM, Greenhalgh T. Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. BMJ 2004;328:1312–15. 10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boynton PM. Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire. BMJ 2004;328:1372–5. 10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawłowska I, Kocić I. Rational use of medicines in the hospitals of Poland: role of the pharmacists. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2014;21:372–7. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbar P, Stefaniuk K. The role of the pharmacist in palliative care: results of a survey conducted in Australia and Canada. J Palliat Care 2002;18:287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ise Y, Morita T, Katayama S, et al. The activity of palliative care team pharmacists in designated cancer hospitals: a nationwide survey in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:588–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veggeland T, Dyb S. The contribution of a clinical pharmacist to the improvement of medication at a geriatric hospital unit in Norway. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2008;6:20–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford GB, Price SD. Team working: palliative care as a model of interdisciplinary practice. Med J Aust 2003;179(6 Suppl):32–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ventafridda V. According to the 2002 WHO definition of palliative care… Palliat Med 2006;20:159 10.1191/0269216306pm1152ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgsteede SD, Rhodius CA, De Smet PA, et al. The use of opioids at the end of life: knowledge level of pharmacists and cooperation with physicians. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67:79–89. 10.1007/s00228-010-0901-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussainy SY, Box M, Scholes S. Piloting the role of a pharmacist in a community palliative care multidisciplinary team: an Australian experience. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:16 10.1186/1472-684X-10-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connor M, Pugh J, Jiwa M, et al. The palliative care interdisciplinary team: where is the community pharmacist? J Palliat Med 2011;14:7–11. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson S, Wahler R, Brown J, et al. Impact of pharmacist intervention on clinical outcomes in the palliative care setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011;28:316–20. 10.1177/1049909110391080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas C, Glare PA, Sykes JV. Contribution of a liaison clinical pharmacist to an inpatient palliative care unit. Palliat Med 1997;11:209–16. 10.1177/026921639701100305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilby KJ, Mohamad AA, AlYafei SA. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy services offered for palliative care patients in qatar. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2014;28:212–5. 10.3109/15360288.2014.938884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]