Abstract

Medicines are the most common intervention to improve health. The number of medicines taken by older people in the UK has been steadily increasing for the last three decades. Polypharmacy is a term that refers to either the prescribing or taking many medicines. Concerns about the risks of polypharmacy in primary and secondary care are growing, supported by evidence which associates polypharmacy with increased adverse drug events, hospital admissions, increased healthcare costs and non-adherence. In the UK, this can largely be attributed, over the last 20 years, to the greater availability of evidence-based treatments promoted through therapeutic guidelines which are designed for single conditions, rather than addressing the multimorbidity that affects many older people. There is also currently a paucity of evidence-based national guidance around reducing and stopping medication and incorporating the patient perspective. This paper reviews current UK literature around polypharmacy including a description of four key resources which all make use of international literature and all focus on the medication aspects of polypharmacy from a clinician's perspective. The patient-centred approach combines both clinical health professionals and patient perspective. Developed using existing resources, it is designed to assist with collaborative (patient and clinician based) medication review to inform decisions around deprescribing and address polypharmacy as part of overall strategies to optimise medicines for the patient. Presented as a diagrammatic representation in seven steps, it also includes guidance on points to consider, actions to take and questions to ask in order to reduce polypharmacy and undertake deprescribing safely.

Keywords: EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), Evidence based medicine, GERIATRIC MEDICINE, PHARMACOTHERAPY, PRIMARY CARE

Introduction

Over one-third of people over 75 years in the UK take four or more medicines regularly1 and this increases to an average of seven medications per person per day in nursing homes.2 The number of medicines taken by older people in the UK has been steadily increasing for the last three decades.

Polypharmacy is a term that refers to either the prescribing or taking many medicines. For many years, it referred to the prescription or use of more than a certain number of medicines, at least four or five or more medicines per day.3 More recently, it has been used in the context of prescribing or taking more medicines that are clinically required, as the number of medicines taken was of limited clinical value in interpreting individual potential problems.

The UK-based King’s Fund4 helpfully divides the definition of polypharmacy into ‘appropriate’ and ‘problematic’ polypharmacy which the authors of this paper believe supports distinguishing those patients who benefit from multiple medicines and those who would benefit from review and reduction of multiple medicines.

This paper will provide an overview of key guidance from the UK about polypharmacy and introduce a tool to support patient-centred practice. The tool is designed to aid clinicians in providing the kind of robust, evidence-based, patient-centred, holistic medication review they would wish for their own family and friends.

There are a number of factors affecting the increase in prescribed medicines including; the advent of evidence-based medicine; increase in multiple morbidity and longevity; promotion of age-independent access to the increasing number of treatments and the increasing expectations for treatment from patients and their families. These have made polypharmacy the ‘rule’ rather than the ‘exception’ for many patients. Medicines are the most common intervention to improve health and concerns about the risks of polypharmacy in primary and secondary care are growing, supported by evidence which associates polypharmacy with increased adverse drug events, hospital admissions, increased healthcare costs and non-adherence.3 4 5 6 This has led to the suggestion that ‘Polypharmacy itself should be conceptually perceived as a “disease” with potentially more serious complications than those of the diseases these different drugs have been prescribed for’.7 While this is a bold and perhaps controversial statement, it clearly illustrates the pervasive and potentially serious nature of polypharmacy as an issue within healthcare.

Terminology

There are a number of terms which have come into use over recent years to describe multiple medicines use which are linked to polypharmacy. These include oligopharmacy, deprescribing and hyperpolypharmacy (see box 1): while these terms may be found in the literature, their usefulness is limited by the lack of broad use and the many factors, other than medicine number, that influence polypharmacy.

Box 1. Polypharmacy terminology and definitions.

▸ Appropriate polypharmacy ‘Prescribing for an individual for complex conditions or for multiple conditions in circumstances where medicines use has been optimised and where the medicines are prescribed according to best evidence’.4

▸ Problematic polypharmacy ‘the prescribing of multiple [medicines] inappropriately, or where the intended benefit of the [medicines are] not realised’.4

▸ Oligopharmacy seeks to promote the deliberate avoidance of polypharmacy, which if considered in terms of numbers of medicines, is the prescribing of less than 5 prescription drugs daily.8

▸ Deprescribing is the complex process required for the safe and effective cessation (withdrawal) of inappropriate medication, recognising that much of the evidence to support stopping medicines is empirical and based on the patient's physical functioning, co-morbidities, preferences and lifestyle.9

▸ Hyperpolypharmacy/excessive polypharmacy is a new term referring to the prescribing of 10 or more medicines and the phrase has come into use to distinguish it from polypharmacy, which is increasingly common.10 11

Understanding the increase in polypharmacy and the challenges

In the UK, this can largely be attributed, over the last 20 years, to the greater availability of evidence-based treatments promoted through therapeutic guidelines. The use of antiplatelet agents post myocardial infarction and stroke are a good example. However, until now, guidelines have been written for management of single disease states. Patients with long-term conditions, especially older people, commonly suffer from a number of conditions and these guidelines are designed for single condition treatment. In addition, each condition is often treated by separate clinicians and the lack of a contemporaneous medication record, available to all healthcare providers and patients in the UK, means that problematic polypharmacy can often ensue. With the increase in the number of medicines available for purchase without prescription and the poor co-ordination and communication of clinicians managing medicines, accurate medication review is often a challenge. Recent work12 has described the challenge to junior doctors, in both attitudes and awareness, of medication review in a hospital.

Prescribers caring for patients with multiple morbidities are further challenged by the absence of evidence-based national guidance around reducing and stopping medication and incorporating the patient perspective. In addition, it is difficult to know how to address the various interconnected factors associated with multimorbidities and frailty that prevent medicines optimisation.

Optimising medicines through managing polypharmacy: current literature

In order to address problematic polypharmacy, clinicians need a structured approach which is flexible enough to be individualised. There are a number of useful documents1 3 4 5 recently published to support medication review in the context of polypharmacy.

NHS Scotland and The Scottish Government produced Polypharmacy Guidance in October 2012, and this was recently updated in March 2015. The 2012 guidance outlines the rationale for addressing polypharmacy, identifies patient groups who may benefit from polypharmacy related medicines review and the general content of the review. While the document recommends using SPARRA (Scottish Patients at Risk of Readmission and Admission) prediction tool data to identify local high-risk groups, this concept is readily transferable to other geographies. The second section gives clinical information using evidence-based sources to support conducting a review explaining the meaning of and including numbers needed for to treat and numbers needed to harm for individual drugs and drug groups. The drug review process described is clinically focused and supports the practitioner with the clinical information needed to conduct an effective review. Risk from high-risk medication is discussed individually and by UK British National Formulary (BNF) categories, as well as identification of clinical conditions of patients which can increase the risks from polypharmacy.

The updated 2015 guidance by the Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group provides additional background information about the interplay between polypharmacy, frailty and multi-morbidity. More detail on populations to target when identifying high-risk groups is given and there is a new approach to polypharmacy medication review in the form of a seven-step approach to managing medication from a drug perspective. This is a useful method of considering each medication in terms of the benefit and risk to an individual patient, including an evidence-based approach. The updated guide also includes key issues for medication review on a drug by drug and drug class basis listed by BNF categories. A new addition to the guidance is the ‘hot topics’ section which highlights key conditions and drugs which merit special attention, such as review of antipsychotic medication, falls risks with medication etc.

NHS Wales Health Board published Polypharmacy: Guidance for Prescribing in Frail Adults which is a practical introduction to practitioners who are interested in implementing polypharmacy reviews in their workplace. The information is presented as a one-page flow-chart-based summaries of background; drug review process; high-risk medication; frailty and shortened life expectancy, ending with useful links. A more detailed guide is also available which includes an explanation of the practicalities for stopping specific groups of medicines. The appendices contain an example medicines review leaflet for patients and a list of helpful resources as well as references.

The UK King’s Fund produced a 68-page 2013 report which provides a detailed examination of how polypharmacy manifests in different care settings, key issues and areas for development. It introduces the concept of appropriate and problematic polypharmacy. It highlights both the benefits of appropriate polypharmacy and the risks of problematic polypharmacy in clinical and patient-centred term and both medicines waste and poor adherence to treatment are included in the problems of problematic polypharmacy. Recognising that most evidence for use of medicines is for single conditions, it identifies the gap in multimorbidity guidelines (which is currently being addressed by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Recommendations for practice are given regarding shortened life expectancy and managing long-term conditions, including the importance of overview by one clinical team of all long-term conditions.

Finally, the PrescQIPP programme13 has produced a number of resources to support practitioners in reducing polypharmacy. The web pages outline the background to this area and describe the current work of the project, including a landscape review of polypharmacy and deprescribing, a bulletin and support for general practitioner practice audit to identify patients at risk. The Safe and Appropriate Medicines Briefing (June 2013) outlines the top ten therapeutic areas/drug classes to focus on. The Safe and Appropriate Medicines Bulletin (June 2013) uses BNF classes to highlight potential clinical and cost issues with medication to support medicines optimisation and reduce polypharmacy. There is a useful patient information leaflet provided as an appendix and a poster which summarises the work undertaken. The most recent addition to these resources is the ‘landscape review’, a survey of CCGs and CSUs systems and tools used, meaning of and attitudes to polypharmacy and deprescribing, local projects and challenges to implementation. Key findings include the difficulty of the terminology for patients and the need for public education and the desire for sharing resources.

A patient-centred approach

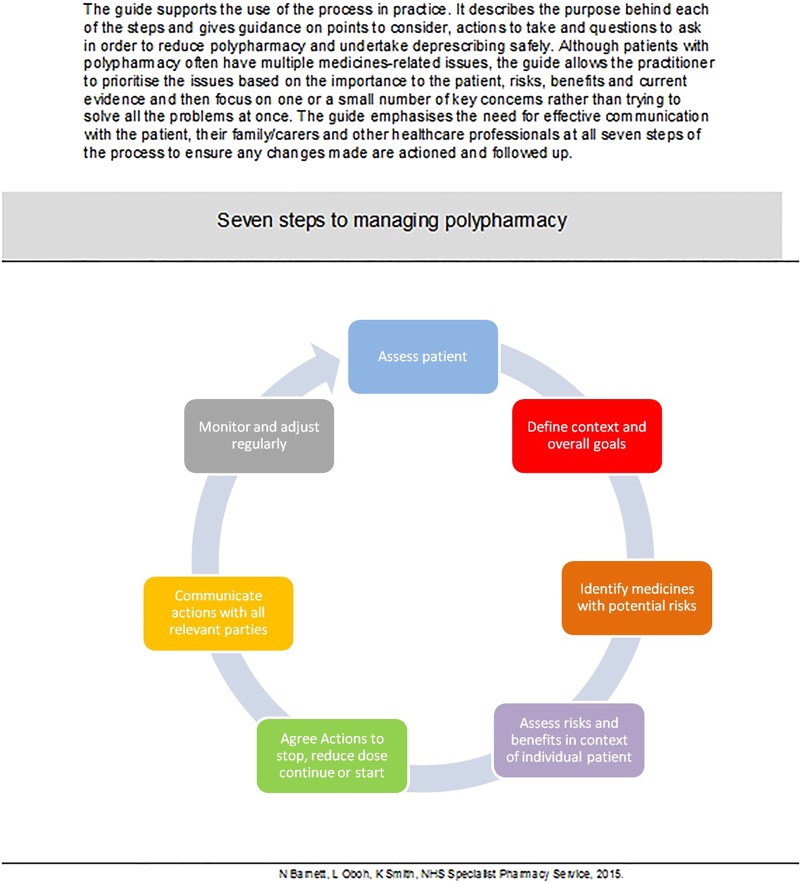

While the current resources provide a comprehensive guide to the identifying and managing polypharmacy, they mostly focus on the clinician's perspective in undertaking identification of problematic polypharmacy and subsequent management. In order to address polypharmacy, we suggest that clinicians would benefit from the addition of a patient-centred approach and structured combining both clinician and patient perspective, which is flexible enough to be individualised. Figure 1 illustrates a process which has been developed to support this.

Figure 1.

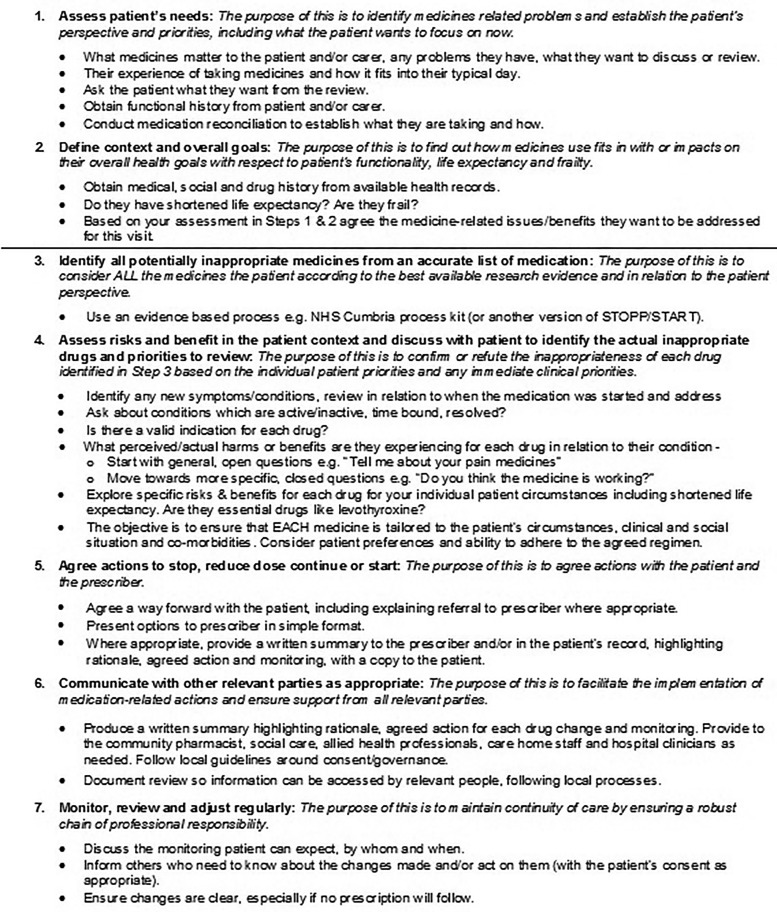

The seven steps explained.

The process, with explanatory notes, is shown in figure 1. It has been developed using the expertise of the UK Medicines Information14 service to provide the evidence, the expert practice of senior practitioners caring for patients with polypharmacy issues and has had input from patients.

The explanatory notes that follow the diagrammatic representation of the process offers the reader explanation of the purpose behind each of the seven steps, guidance on points to consider, actions to take and questions to ask in order to reduce polypharmacy and undertake deprescribing safely. Although patients with polypharmacy often have multiple medicines-related issues, the written guidance allows the practitioner to prioritise the issues based on the importance to the patient, risks, benefits and current evidence and then focus on one or a small number of key concerns rather than trying to solve all the problems at once. It emphasises the need for effective communication with the patient, their family/carers and other healthcare professionals at all seven steps of the process to ensure any changes made are actioned and followed up.

This process adds to published resources through focus on medication review from the patient perspective and is designed to support clinicians in addressing polypharmacy as part of overall medicines optimisation strategies. For more information including a summary of key documents and list of useful resources, see http://www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/en/Communities/NHS/SPS-E-and-SE-England/Meds-use-and-safety/Service-deliv-and-devel/Older-people-care-homes/Polypharmacy-oligopharmacy--deprescribing-resources-to-support-local-delivery/

Using the process in practice

This is designed to assist with collaborative medication review and decisions around deprescribing in the context of polypharmacy and aims to address polypharmacy as part of overall medicines optimisation strategies.15 It is anticipated that following the process from start to finish will ensure that deprescribing is done in a safe, effective, co-ordinated and efficient way to optimise medicines use and produce patient related outcomes in addition to clinical markers. A multiprofessional approach, led by a clinician with the right expertise to undertake medication reviews for older people is helpful in ensuring the process delivers the right outcomes for all aspects of medicines related care. It can be used in successive consultations to address one or a small number of polypharmacy issues identified in the context of the patients’ overall goals. While it is likely to be most applicable in community settings, the principles can be applied to all patient care settings and clinician encounters with patient where medicines are discussed or reviewed.

Summary

Polypharmacy is associated with an increased risk of adverse effects, falls, drug interactions, drug disease interactions, drug errors and poor adherence of medicines. There are a number of UK resources that support management from a clinician's perspective. This process builds on existing work to create a patient-centred approach. We hope that it will assist practitioners in patient-centred polypharmacy management towards overall medicines optimisation for patient benefit.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr Rupert Payne for commenting on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.NHS Scotland and The Scottish Government. Polypharmacy Guidance, October 2012. http://www.central.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/upload/Polypharmacy%20full%20guidance%20v2.pdf

- 2.Barber N, Alldred DP, Raynor DK, et al. Care homes’ use of medicines study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/18/5/341.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.NHS Wales Health Board. Polypharmacy: Guidance for Prescribing in Frail Adults Practical guide, full guidance, BNF sections to target. May 2013. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/documents/814/PrescribingForFrailAdults-ABHBpracticalGuidance%5BMay2013%5D.pdf

- 4.Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation making it safe and sound. Kings Fund, 2013. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Scotland and The Scottish Government. Polypharmacy Guidance, March 2015. http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/DC20150415polypharmacy.pdf

- 6. Describing deprescribing. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2014;52:25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1648–54. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Mahoney D, O'Connor MN. Pharmacotherapy at the end-of-life. Age Ageing 2011;40:419–22. 10.1093/ageing/afr059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:827–34. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Pearson SA, et al. High risk prescribing in older adults: prevalence, clinical and economic implications and potential for intervention at the population level. BMC Public Health 2013;13:115 10.1186/1471-2458-13-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, et al. Polypharmacy status as an indicator of mortality in an elderly population. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1039–48. 10.2165/11319530-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jubraj B, Marvin V, Poots AJ, et al. A pilot survey of junior doctors’ attitudes and awareness around medication review: time to change our educational approach? Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2015;22:243–8. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See http://www.prescqipp.info/projects/polypharmacy-and-deprescribing and http://www.prescqipp.info/safe-appropriate-medicines-use-deprescribing/viewcategory/190-safe-and-appropriate-medicines-use (accessed 23 Jul 2015).

- 14. http://www.ukmi.nhs.uk/

- 15.Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines Optimisation: Helping patients to make the most of medicines. Good practice Guidance for healthcare professionals in England. May 2013. http://www.rpharms.com/promoting-pharmacy-pdfs/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf