Abstract

Objective

To investigate the feasibility and potential impact of a pharmacy care intervention, involving motivational interviews among patients with acute coronary syndrome, on adherence to medication and on health outcomes.

Methods

This article reports a prospective, interventional, controlled feasibility/pilot study. Seventy one patients discharged from a London Heart Attack Centre following acute treatment for a coronary event were enrolled and followed up for 6 months. Thirty two pharmacies from six London boroughs were allocated into intervention or control sites. The intervention was delivered by community pharmacists face-to-face in the pharmacy, or by telephone. Consultations were delivered as part of the New Medicine Service or a Medication Usage Review. They involved a 15–20 min motivational interview aimed at improving protective cardiovascular medicine taking.

Results

At 3 months, there was a statistically significant difference in adherence between the intervention group (M=7.7, SD=0.56) and the control group (M=7.0, SD=1.85), p=0.026. At 6 months, the equivalent figures were for the intervention group M=7.5, SD=1.47 and for the controls M=6.1, SD=2.09 (p=0.004). In addition, there was a statistically significant relationship between the level of adherence at 3 months and beliefs regarding medicines (p=0.028). Patients who reported better adherence expressed positive beliefs regarding the necessity of taking their medicines. However, given the small sample size, no statistically significant outcome difference in terms of recorded blood pressure and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol was observed over the 6 months of the study.

Conclusions

The feasibility, acceptability and potentially positive clinical outcome of the intervention were demonstrated, long with a high level of patient acceptability. It had a significant impact on cardiovascular medicine taking adherence. But these findings must be interpreted with caution. The intervention should be tested in a larger trial to ascertain its full clinical utility.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01920009.

Keywords: pharmacy care, adherence, cardiovascular medicines, motivational interviews

Background

Despite progress since the 1950s, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in the UK. There are currently an estimated 2.3 million people living with coronary heart disease who are in need of secondary prevention medication.1 Yet long-term adherence to secondary prevention therapies is poor. Reported adherence to medication regimens post-myocardial infarction (MI) ranges from 13% to 60%.2

Research indicates that approximately a quarter to a third of patients with CVD discontinue their medication.3 4 This problem is associated with drug wastage and, more importantly a loss of clinical benefit and potentially serious health consequences.5

There is robust evidence that consistent use of secondary prevention medication after a coronary event is associated with lower adjusted mortality as rates compared with those among subjects who are not consistent medicine takers.6 For example, patients discontinuing clopidogrel within a month after hospital discharge following acute MI and drug eluting stent placement are significantly more likely to have an adverse outcome in the subsequent 11 months.7

Strategies to tackle non-adherence can involve community pharmacy service providers. In England, Medicine Use Reviews (MURs) were first instituted in 2005.8 They are intended to help identify and address problems that patients experience in relation to taking medicines. More recently, the New Medicines Service (NMS)9 was introduced in order to promote adherence in patients taking medicines for the first time for a range of long-term conditions. Both these services are NHS (The UK National Health Service) remunerated services of community pharmacists.

Other strategies for supporting enhanced medicines usage involve motivational interviewing. This can be defined as a client-centred, directive, form of counselling intended to foster behavioural change by increasing awareness of ambiguities and internal dissonance.10 Motivational interviewing has been employed in many clinical settings and with multiple patient groups.11–13

Pharmacists are increasingly employing patient-centred approaches to support patients taking medicines for long-term conditions. Yet, there is currently no adequate evidence base regarding the feasibility and effectiveness of motivational interviewing to promote medication adherence in the pharmacy setting. This study was carried out to address this shortcoming and to evaluate the potential effectiveness of a community pharmacy intervention for patients discharged following a MI with secondary prevention medication. It also explored issues relating to improving communication and collaboration between hospital and community pharmacists.

Objectives

To investigate the potential impact on outcomes of a pharmacy care intervention involving hospital pharmacy referral to community pharmacy services and motivational interviewing on adherence to secondary prevention medication among recently discharged coronary heart disease patients.

Methods

Design

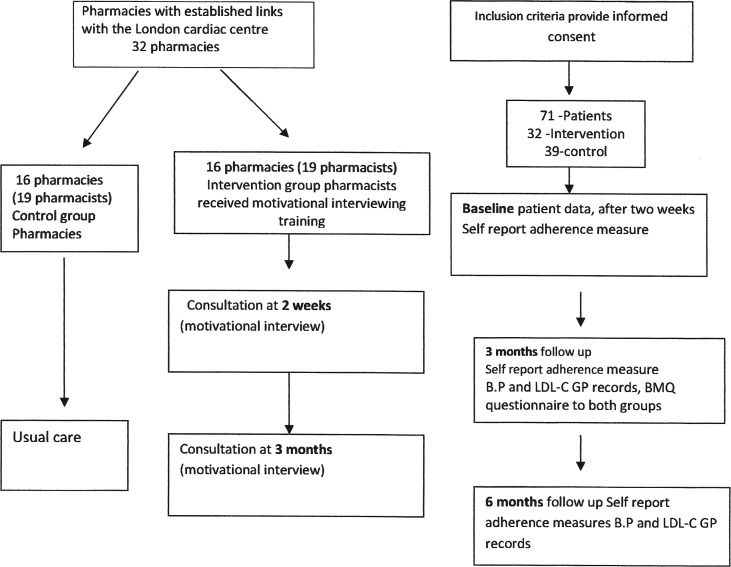

The study was designed as a prospective, feasibility/pilot, controlled trial. The primary outcome was adherence to cardiovascular medication (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design. BMQ, Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire; GP, general practitioner; BP, blood pressure.

Study setting and study population

The study was undertaken in collaboration with community pharmacists in East London and the North East London Pharmaceutical Committee (NELLPC) and with practitioners and patients from a London Heart Attack Centre. The study gained research ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee (North West—Preston), from the R&D Joint Research Management Office, Queen Mary Innovation Centre and from the R&D Office, University College London. The study population included patients with coronary heart disease with a discharge diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome.

Recruitment

There were two stages of recruitment; recruitment of pharmacies and recruitment of patients.

Community pharmacists/pharmacies were recruited through NELLPC and assigned as below to either the intervention or control group. The inclusion criteria were: (1) pharmacists willing to counsel patients and interested in attending further training; (2) have a consultation area and have access to a telephone (land line or mobile); (3) the pharmacists were knowledgeable about the NMS and MUR, and had contacts with or were willing to contact general practitioners (GPs) and also willing to contact patients to invite them for a consultation.

Allocation to intervention and control groups

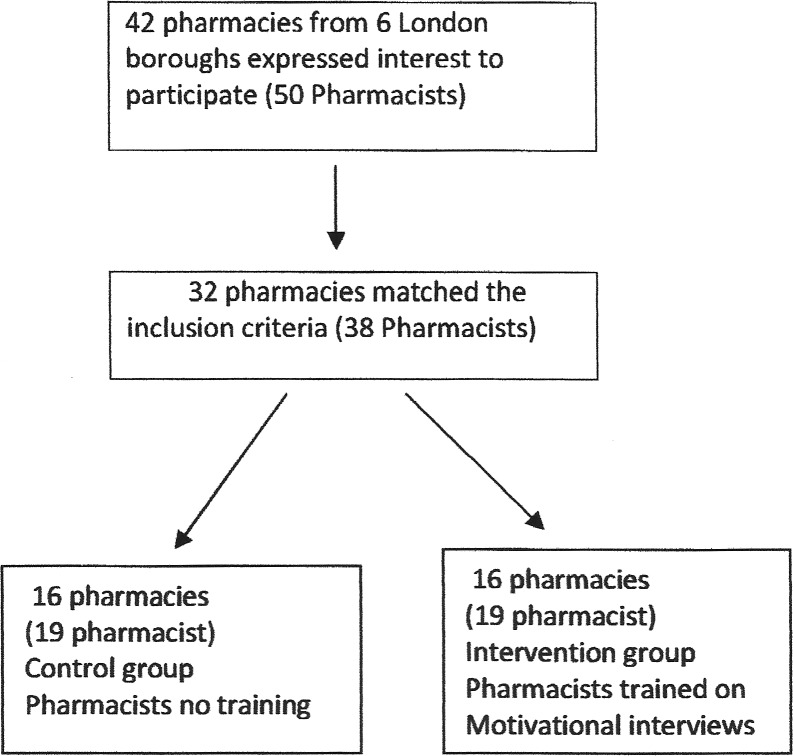

While simple randomisation of the entire sample was not possible, procedures were adopted to ensure comparability of the intervention and control groups for this study. Pharmacy recruitment was all done through NELLPC. Pharmacists informed of study by two different routes. First, by email 22 pharmacies responded that they wished to take part. These were randomised to intervention and control by an independent statistician at University College London School of Pharmacy. This process was concealed from the researcher and the research team and was performed at pharmacy level to avoid contamination of controls.

To achieve sufficient numbers a second group were invited to participate during a professional meeting and 10 pharmacies met the inclusion criteria. As the dates of motivational interview training had to be set in advance, pharmacists wishing to take part and able to attend the predetermined dates were allocated to the intervention group. The control group was a matched sample drawn from remaining pharmacists who expressed a wish to take part, see figure 2. Eligible patients were prior to discharge given introductory information about the study by the researcher and supplied with further details as requested. They were then asked if they would like to participate. The full eligibility and exclusion criteria are described in online supplementary table S1. After recruitment, patients were assigned into groups according to the primary care pharmacy at which they usually refill their prescriptions. Patients who normally refill their prescription from the intervention pharmacies were assigned to the intervention group and patients who regularly refilled their prescription in the pharmacies that were control sites were assigned to the control group.

Figure 2.

Pharmacy randomisation.

Blinding

The research pharmacist responsible for the data analysis was blind to the above group allocations. The GPs and GP practices from which data regarding blood pressures (BPs) and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were collected were also blind, unless referral of a patient by a community pharmacist took place. However, due to the nature of the intervention it was not possible to blind the hospital and community pharmacists delivering the intervention or the patients receiving it.

Sample size

Power calculations were based on the findings of previous studies in which the primary outcome was adherence. For instance, a similar study14 reported a 33% increase in adherence with a margin error of 5% and confidence interval 95%. Given these and allied data the enrolment target was set at 200 patients.

Pharmacist training

Pharmacists in the intervention delivery group participated in a 2-day training session on motivational interviewing, followed by a subsequent booster session, given by an expert psychologist (KF), all the training sessions on motivational interviewing including the booster session were completed before inclusion of patients. An additional training session on the use of secondary prevention medicines after a MI was given by a consultant pharmacist (SA).

Liaison with GPs

The GPs were asked for their written consent to providing the results of BP measurements and LDL-C levels during the duration of the study with patient consent.

The intervention

The intervention was developed on the basis of a previous systematic review.15 A ‘consultation chart’ (a pro forma guide the motivational interview process) was developed by referring to a previous randomised controlled trial involving patients with hypertension,16 which generated statistically significant impacts on adherence. In this instance, trained research assistants rather than pharmacists used motivational interviewing techniques. The intervention was designed to include elements of motivational interviews and to be integrated into the existing NMS and MUR pharmacy services so that the participating community pharmacists would be able to claim funding for their work.

On discharge patients receiving the intervention were initially given usual care from a hospital pharmacist. This consisted of a review of medications use, counselling on secondary prevention and any other additional prescribed medication usage, an antiplatelet medication leaflet and referral to cardiac rehabilitation. Patients were subsequently contacted by a pharmacist to arrange a community pharmacy consultation.

The first community pharmacy consultation typically took place at around 2 weeks after hospital discharge on either a face-to-face basis or by telephone as recent evidence shows that motivational interviewing can be effectively delivered by telephone17 and lasted for 15–20 min. The substance of these sessions is detailed in online supplementary box S1, also comparison of motivational interviewing with traditional counselling can be found in online supplementary table S2.

The control group

On discharge control group patients received usual care from a hospital pharmacist (as described above).

Outcome measures and data collection

The primary outcome measure used was self-reported adherence with the coronary artery disease medication regimen prescribed, assessed via the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale MMAS8.18 The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire-Specific (BMQ-S)19 was also used at 3 months after discharge; to evaluate the effect of the intervention on patients’ beliefs regarding their medication and to examine the relationship between patients’ beliefs regarding their medicines and adherence, this study did not evaluate changes in patients’ beliefs over time.

Secondary outcome measures included BP and LDL-C. Baseline data collected from the hospital included gender, age, diagnosis, BP, LDL-C, ethnicity, post code and GP practice, all patients enrolled in the study were discharged on four classes of medication (antiplatelets, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and statins) as recommended for secondary care of patients following a MI.20 Data collection took place at 2 weeks after hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months (figure 1).

Analysis

Data were analysed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences V.22 for Windows. An independent t test was used to compare the differences in the intervention group and the control group adherence means and also to compare the differences between the BPs and LDL-C levels (significance was set at the 5% level). A χ2 test was performed to examine the relationship between beliefs about medication and adherence to the cardiac medication at 3 months. The scores from the BMQ-S were handled according to standard procedures for analysis of the questionnaire.19

Results

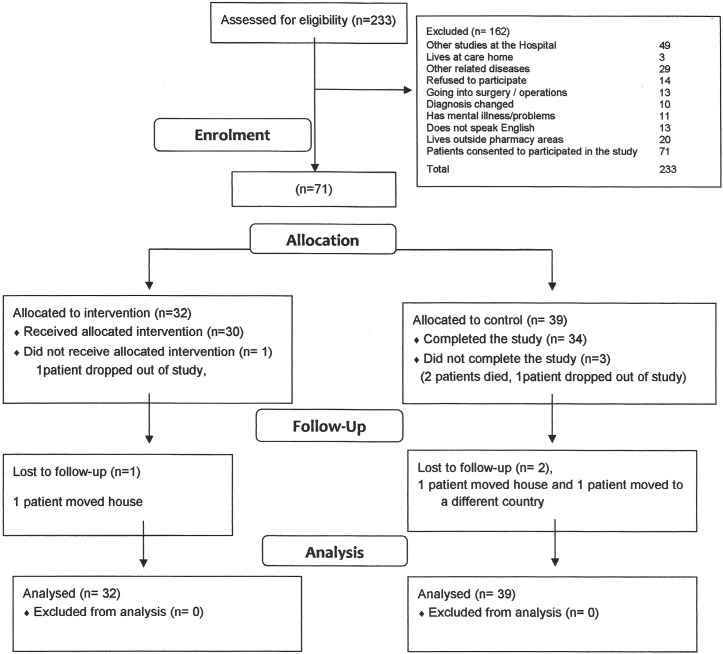

In the 4 months available for recruitment for this study 71 patients were enrolled consecutively. Recruitment is commonly one of the biggest challenges for any study. In this instance it was undertaken by a single researcher. On average it was possible to recruit 2–3 patients per day, excluding those occasions on which no eligible patients presented. Out of a total of 233 patients assessed for eligibility only 14 individuals refused to participate. Others were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria as illustrated in the consort diagram—see figure 3.

Figure 3.

Study recruitment.

The NHS users recruited were predominantly male (76%) and as shown in online supplementary table S3, most were in their sixties and seventies. It was found that 51 of the patients involved had an ST-elevation MI (STEMI). The remaining 20 had suffered a non-STEMI (NSTEMI).

As a feasibility/pilot study, this was not powered to measure clinical outcomes and was designed only to provide an indication of potential effectiveness. Hence, the findings presented here should be interpreted with caution.

Impact on adherence

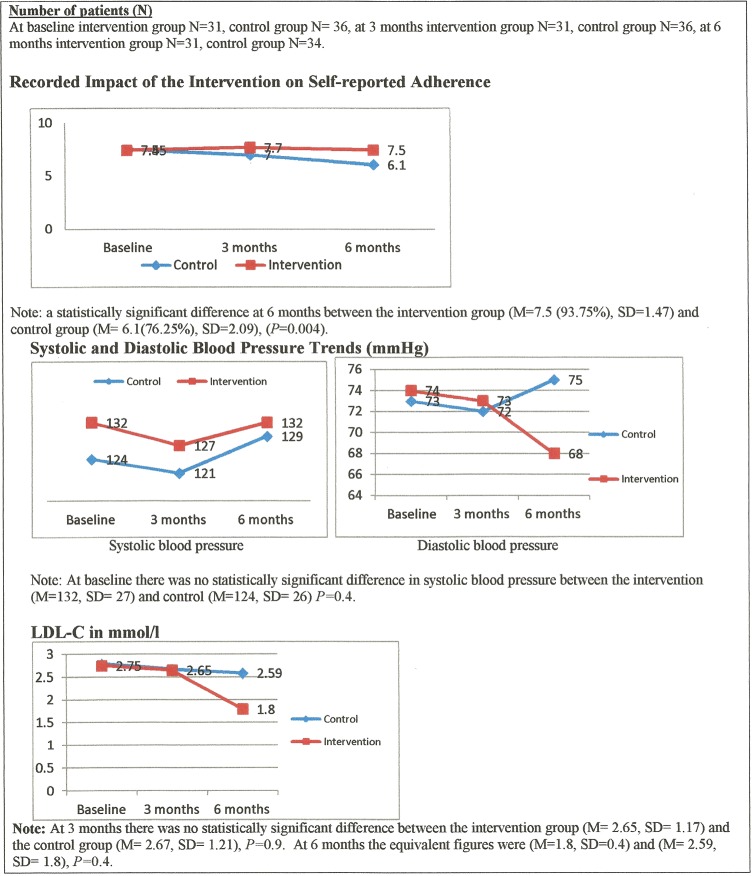

As indicated in figure 4, there was at baseline no difference in self-reported adherence rates between the intervention group (M=7.45, SD=0.79) and the control group (M=7.5, SD=0.93), p=0.85. However, at 3 months there was a statistically significant difference in adherence between the intervention group (M=7.7, SD=0.56) and the control group (M=7.0, SD=1.85), p=0.026. There was also a statistically significant difference at 6 months between the intervention group (M=7.5 (93.75%), SD=1.47) and the controls (M=6.1 (76.25%), SD=2.09), p=0.004. Note: (M=mean).

Figure 4.

Results on adherence and outcomes.

Beliefs about medicines

There was a statistically significant relationship between the level of adherence at 3 months and the beliefs regarding medicines as evaluated by the BMQ-S (p=0.028). Patients with greater levels of self-reported adherence showed more positive beliefs regarding the necessity of their medicines.

Results on clinical outcomes: BP and LDL-C

It was disappointing that for both BP and LDL-C around two-thirds of patients in both groups did not have a follow-up evaluation from their GPs. This may help explain why at 3 months there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention group (M=127, SD=20) and the control group in systolic BP (M=121, SD=20), p=0.3.

Similarly at 6 months there was no statistically significant result between the intervention group (M=132, SD=11) and the control group (M=129, SD=12), p=0.6 (figure 4). Nevertheless, systolic BP in the intervention group at 3 months decreased by 5 mm Hg and at 6 months returned to the same as baseline. By contrast, figure 4 also shows that in the control group systolic BP had decreased by 3 mm Hg at 3 months but increased by 5 mm Hg at 6 months.

Likewise, there was no significant difference in diastolic BP between the intervention group at baseline (M=74, SD=7.2) and the control group (M=73, SD=11), p=0.8. At 3 months there was again no statistically significant difference between the intervention group (M=73, SD=11.5) and the controls (M=72, SD=9.9), p=0.84. At 6 months there was similarly no statistically significant result in the intervention group the figures were (M=68, SD=11.7) and in the controls they were (M=75, SD=4.8), p=0.2. Nevertheless, at 6 months mean diastolic BP in the intervention group had decreased by 6 mm Hg from baseline. In the control group diastolic BP had by then increased by 2 mm Hg from baseline.

With regard to the LDL cholesterol levels reported, there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention group's LDL-C at baseline (M=2.75, SD=1.05) and the control group figures (M=2.79, SD=1.4), p=0.9. At 6 months there was a 0.79 mmol/L difference in LDL-C between the intervention group and the control group (figure 4). However, although suggestive of a material difference this result was once again non-significant, possibly because of the small numbers of subjects for whom data were available.

Discussion

This study reports positive findings regarding the potential outcomes of the community pharmacy intervention investigated. Numerous studies have examined patients’ views on services provided by community pharmacists. It has been commonly found that patient awareness of the pharmacist's role outside that of dispensing and non-prescription drug supply is generally low. This could to date have led to an under-utilisation of pharmacist provided clinical services.21 22 Initiatives like the study reported here may over time enhance awareness of the value of pharmacy services in ‘serious’ contexts like posthospital discharge following a cardiac event. Such initiatives might also contribute to the uptake and utility of existing services (ie, the NMS and MURs), and promote improved hospital and community pharmacy communication.

In the latter context, patients’ discharge summaries were forwarded from the participating hospital pharmacy to community pharmacists. Community pharmacy access to patients’ healthcare records is not as yet usually available in the UK or elsewhere. There is evidence that this restricts the capacity of pharmacists’ interventions to improve adherence and resolve other medication-related problems.23 This study demonstrates the potential importance of record sharing between community and hospital pharmacists in improving patient care. The supply of discharge summaries to community pharmacies was achieved by using secure hospital emails and with patient consent. All the stakeholders involved, including the service users taking part, supported the supply of discharge summaries to community pharmacies. This finding is in line with the approach advocated by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS, 2014). The RPS has recently launched ‘a hospital referral to community pharmacy innovators’ Toolkit developed in response to the report ‘Now or Never: Shaping Pharmacy for the Future.24 In the Society's view referrals from hospital to community pharmacies could become routine practice within 5 years.

After 6 months self-reported medication adherence among those receiving motivational support from community pharmacist was 17% greater than that recorded in control patients. This result can be compared with a recent US study25 that found that a phone-based motivational interview improved adherence in the case of antiplatelet medicines by 14% (p<0.01). It is also similar in magnitude to the reported effect of automated text messaging when used to prompt adherence to cardiovascular preventive treatment.26 Other research studies have failed to find similar benefits in relation to the treatment of people who have experienced strokes or other forms of vascular disease.27 28 Nevertheless, there is mounting reason to believe that greater use of well-targeted motivational interventions by community pharmacists could prove to be of substantive value in today's environment. It is also possible that combinations of different types of approaches to enhancing medication taking in high-risk patient groups could have even greater effects.

In this study, a statistically significant relationship was found between reported adherence and medicine takers’ beliefs regarding the necessity of taking their prescribed treatments. Although there remain uncertainties regarding the causal links underpinning such observations, our findings are consistent with other research undertaken in the UK and elsewhere.29 30 Investing in pharmacy led interventions to further promote awareness of the value of taking medicines in high-risk therapeutic situations like post-MI care has the potential to contribute cost-effectively to improved health outcomes.31–34

However, no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients achieving BP and LDL-C reduction targets was found in this trial, which was not adequately powered to identify such effects. To date, most other similar studies have also failed to demonstrate statistically significant results in relation to such proxy clinical outcomes.35–38 A relatively recent review35 concluded that too few pharmacy-based trials are available in this area, and that further larger scale quantitative research involving patients with CVD should be conducted.

More qualitative work examining pharmacists’ experiences of using motivational interviews to enhance adherence should also prove useful. In addition, after a life changing event such as a MI many patients appear to welcome the additional primary care support that appropriately skilled community pharmacists are capable of providing.

The positive responses of GPs involved in this investigation are also informative. Some previous research has indicated that GPs often tend to have negative attitudes towards extending community pharmacists’ clinical roles.39 Yet, the uptake and outcomes of community pharmacy services such as the intervention evaluated here are likely to improve when they are endorsed by GPs and effectively integrated with other primary care services. The findings of this research indicate that, in addition to recent measures aimed at encouraging the employment of pharmacists in GP surgeries, innovative approaches to developing community pharmacy contributions to the care of patients in need of better overall primary care services are also worth further investigation.

This study's main limitations relate to the small sample size and that it was focused on improving care in just one area of North East London; also it included a single centre this limits its perceived effectiveness in different locations and patient populations and also limits the confidence with which its findings can be generalised. Other limitations; it was not possible to formally assess the extent to which all elements of motivational interviews were followed in the delivery of the intervention and ideally, measures of adherence that reduce reliance on self-reported data would also have been valuable. The strengths of the study that this article reports, which was designed as a feasibility pilot controlled trial, include that it used well validated instruments such as the Morisky Scale questionnaire and the BMQ, and that effective blinding procedures were put in place.

Conclusion

This work indicates how enhanced pharmaceutical care could help further improve adherence to medicines and health outcomes in relation to using medicines for preventive purposes among patients recovering from acute coronary events. Moving further towards assuring the optimisation of medicines use in this and other contexts is likely to demand the organisation of a larger multicentre randomised control trial or trials, the design of which should be informed by the findings of this feasibility study.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject

Pharmacist interventions have been shown to be successful in enhancing adherence to cardiovascular medication and improving outcomes of cardiovascular diseases.

Improved adherence to secondary prevention medication for coronary heart disease would promote better clinical outcomes.

Motivational interviewing can be an effective approach to improve health behaviour in people with coronary risk factors.

What this study adds

This pilot study suggests that a behavioural intervention, incorporating motivational interviewing and delivered in a community pharmacy setting, can improve adherence to secondary prevention cardiovascular medication, and corresponding clinical outcomes for patients following a myocardial infarction.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Service Committee (North West—Preston), from the R&D Joint Research Management Office, Queen Mary Innovation Centre, and from the R&D Office, University College London.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Any unpublished data are available by contacting the corresponding author of this paper.

References

- 1.Townsend N, Williams J, Bhatnagar P, et al. Cardiovascular disease statistics, 2014. British Heart Foundation: London, 2014.

- 2.Garavalia L, Garavalia B, Spertus JA, et al. Exploring patients’ reasons for discontinuance of heart medications. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009;24:371–9. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ae7b2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter S, Taylor D, Levenson R. A question of choice: Compliance in medicine taking. A preliminary review. London: Medicines Partnership, 2nd ed. 2003. http://www.npc.co.uk/med_partnership/resource/major-reviews/a-question-of-choice.html.

- 4.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;117:1028–36. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trueman P, Taylor D, Lowson K, et al. Evaluation of the scale, causes and costs of waste medicines. Report of DH funded national project York: and London: York Health Economics Consortium and the School of Pharmacy, University of London, on behalf of the Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newby LK, LaPointe NMA, Chen AY, et al. Long-term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation 2006;113:203–12. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.505636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spertus JA, Peterson E, Rumsfeld JS, et al. The Prospective registry evaluating myocardial infarction: events and recovery (PREMIER)—evaluating the impact of myocardial infarction on patient outcomes. Am Heart J 2006;151:589–97. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. http://www.rpharms.com/health-campaigns/medicines-use-review.asp.

- 9. http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/

- 10.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change. New York: Guilford Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing in service to health promotion. The art of health promotion: practical information to make programs more effective. Am J Health Promot 2004;18:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilorio C, Resnicow K, McDonnell M. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: a pilot study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2003;14:52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen MI, Ryan C, Rigsby M. Motivational enhancement and MEMS review to improve medication adherence. Behav Change 2002;19:183–90. 10.1375/bech.19.4.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obreli-Neto PR, Guidoni CM, de Oliveira Baldoni A. Effect of a 36- month pharmaceutical care program on pharmacotherapy adherence in elderly diabetic and hypertensive patients. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:642–9. 10.1007/s11096-011-9518-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalal ZS, Smith F, Taylor D, et al. Pharmacy care and adherence to primary and secondary prevention cardiovascular medication: a systematic review of studies. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2014;21: 238–44. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogedegbe G, Chaplin W, Schoenthaler A. A practice-based trial of motivational interviewing and adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:1137–43. 10.1038/ajh.2008.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teeter BS, Kavookjian J. Telephone-based motivational interviewing for medication adherence: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med 2014;4:372–81. 10.1007/s13142-014-0270-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–54. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire; the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24. 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Clinical guidelines 48 MI. Secondary prevention, Secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a myocardial infarction. London: NICE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gidman W, Ward P, McGregor L. Understanding public trust in services provided by community pharmacists relative to those provided by general practitioners: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000939 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. Feedback from community pharmacy users on the contribution of community pharmacy to improving public's health: a systematic review of the peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed literature 1990–2002. Health Expect 2004;7:191–202. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00274.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ref 12.03.29E 002 Sustainable European Community Pharmacies Part of the Solution. Page 2 of 4. Pharmaceutical Group of European Union.

- 24.Hospital referral to community pharmacy: An innovators’ toolkit to support the NHS in England; December 2014 Produced by the RPS Innovators’ Forum.

- 25.Palacio AM, Uribe C, Hazel-Fernandez L, et al. Can phone-based motivational interviewing improve medication adherence to antiplatelet medications after a coronary stent among racial minorities? A randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:469–75. 10.1007/s11606-014-3139-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wald DS, Bestwick JP, Raiman L, et al. Randomised Trial of Text Messaging on Adherence to Cardiovascular Preventive Treatment (INTERACT Trial). PLoS ONE 2014;9:e114268 10.1371/journal.pone.0114268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedegaard U, Kjeldsen LJ, Pottegård A, et al. Multifaceted intervention including motivational interviewing to support medication adherence after stroke/transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 2014;4:221–34. 10.1159/000369380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostbring MJ, Eriksson T, Petersson G, et al. Medication beliefs and self-reported adherence-results of a pharmacist's consultation: a pilot study. Eur J Hosp Pharmacy 2014;21: 102–7. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjölander M, Eriksson M, Glader EL. The association between patients’ beliefs about medicines and adherence to drug treatment after stroke: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003551 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatti ME, Jacobson KL, Gazmararian JA. Relationships between beliefs about medications and adherence. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66:657–64. 10.2146/ajhp080064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:2563–71. 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgado M, Rolo S, Castelo-Branco M. Pharmacist intervention program to enhance hypertension control: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:132–40. 10.1007/s11096-010-9474-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aslani P, Rose G, Chen TF, et al. A community pharmacist delivered adherence support service for dyslipidaemia. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:567–72. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson GM, Fitzmaurice KD, Naunton M, et al. Impact of pharmacist-conducted home visits on the outcomes of lipid-lowering drug therapy. J Clin Pharm Ther 2004;29:23–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai H, Dai H, Hu Y, et al. Pharmacist care and the management of coronary heart disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:461 10.1186/1472-6963-13-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner A, Carey EP, et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve medication adherence and secondary prevention measures after acute coronary syndrome hospital discharge a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:186–93. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yunsheng M, Ira SO, Milagros CR, et al. Randomised trial of a pharmacist-delivered intervention for improving lipid-lowering medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease. Cholesterol 2010;2010:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffray M, Bond C, Watson M, et al. The Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN study: a randomised controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract 2007;24:189–200. 10.1093/fampra/cml075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saramunee K, Krska J, Mackridge A, et al. How to enhance public health service utilization in community pharmacy?: General public and health providers’ perspectives. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014;10:272–84. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]