Abstract

Objective

To test the practicality, acceptability and feasibility of recruitment, data collection, blood pressure (BP) monitoring and pharmaceutical care processes, in order to inform the design of a definitive randomised controlled trial of a pharmacist complex intervention on patients with stroke in their own homes.

Methods

Patients with new stroke from acute, rehabilitation wards and a neurovascular clinic (NVC) were randomised to usual care or to an intervention group who received a home visit at 1, 3 and 6 months from a clinical pharmacist. Pharmaceutical care comprised medication review, medicines and lifestyle advice, pharmaceutical care issue (PCI) resolution and supply of individualised patient information. A pharmaceutical care plan was sent to the General Practitioner and Community Pharmacy. BP and lipids were measured for both groups at baseline and at 6 months. Questionnaires covering satisfaction, quality of life and medicine adherence were administered at 6 months.

Results

Of the 430 potentially eligible patients, 30 inpatients and 10 NVC outpatients were recruited. Only 33/364 NVC outpatients (9.1%) had new stroke. 35 patients completed the study (intervention=18, usual care=17). Questionnaire completion rates were 91.4% and 84.4%, respectively. BP and lipid measurement processes were unreliable. From 104 identified PCIs, 19/23 recommendations (83%) made to general practitioners were accepted.

Conclusion

Modifications to recruitment is required to include patients with transient ischaemic attack. Questionnaire response rates met criteria but completion rates did not, which merits further analysis. Lipid measurements are not necessary as an outcome measure. A reliable BP-monitoring process is required.

Keywords: pilot randomised control trial, complex intervention, pharmacist, medication review

EAHP Statement 5: Patient Safety and Quality Assurance

Introduction

National and European stroke guidelines state that patients requiring admission to hospital should be admitted to a stroke unit staffed by a coordinated multidisciplinary stroke team.1 2 In the acute setting, this usually includes a specialist clinical pharmacist, while, on discharge from hospital, pharmaceutical care is generally managed by non-specialist community pharmacists. A proportion of patients with stroke on discharge do not have contact with the community pharmacist because they are unable to visit the pharmacy in person.3 4 Qualitative studies in homes of patients with stroke have identified the barriers and difficulties which patients experience when taking their medicines.3 4 Stable medicine routines, appropriate medicine and illness beliefs, communication at the secondary/primary care interface, individualised information and practical help from healthcare staff about managing medicines are the key factors in optimising medicine-taking behaviour.3 4

Medication and lifestyle modification may reduce recurrent vascular events in patients with stroke by 80% over 5 years.5 One-third of patients with stroke discontinue secondary prevention medication within 1 year6 and recurrent stroke accounts for approximately 25% of all strokes.7

There is evidence that pharmacists can manage control of blood pressure (BP) in patients with diabetes with cardiovascular disease to reach targets.8 In patients with stroke, a systematic review of interventions to improve BP through adherence to antihypertensive medicines included one pharmacist-led study.9 The intervention consisted of 6×1 hour face-to-face counselling sessions in 160 patients for 6 months in a hospital outpatient clinic. The design and reporting of this study limits its interpretation.10 Pharmacist telephone interventions in patients with stroke have been shown to help reach secondary stroke prevention goals.11 The Cochrane review of interventions in secondary prevention of stroke12 concludes that there is no clear evidence of change in modifiable risk factors with educational or behavioural interventions alone without any organisational changes. Systematic reviews have concluded that few complex interventions in stroke have been ‘adequately developed or evaluated’ due to multiple primary outcomes, insufficient statistical powering and poor intervention development.12 13 Our complex intervention is based on previous pharmaceutical needs assessment.3 We propose to undertake a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate a complex intervention14 of structured pharmaceutical care (see online supplementary appendix 1) delivered by a pharmacist to patients with stroke in their own homes with the hypothesis that the intervention will increase the proportion of patients reaching target BP. In line with Cochrane,12 elements of educational and behavioural intervention for patients and their carers/stroke service providers and organisational interventions including associated communication and follow-up with the multidisciplinary team (MDT) would be included. This pilot study assesses the feasibility of the processes required for an RCT to define an appropriate primary outcome measure and potential sample size for a future RCT.

ejhpharm-2016-000918supp001.pdf (284.3KB, pdf)

Objectives

This pilot study aimed at testing the practicality, acceptability and feasibility of recruitment, data collection, BP monitoring and pharmaceutical care processes in order to inform the design of a definitive RCT of a pharmacist complex intervention to patients with stroke in their own homes.

Pilot study outcomes

The outcome was determination of feasibility of the following processes:

Recruitment—consent rate, dropout rate, eligibility criteria, randomisation process

Data collection—availability and accessibility of clinical and prescribing data from primary and secondary care patient records, questionnaire return and completion rates

BP measurement—setting/method/operator, drug treatment effect, variability

Pharmaceutical care—process of identification and method of resolving care issues

Pilot study criteria (proposed—agreed by expert group consensus)

Recruitment—two-thirds of inpatients’ eligibility (50% consent and 10% attrition)

Data collection—clinical and prescribing data accessible at time of retrieval from hospital and general practitioner (GP) computer systems. Questionnaire return and completion rates (90%).

BP—consistency (90%) in measurements taken by clinical pharmacy researcher and nurse in different settings

Pharmaceutical care—identified care issues are recorded, categorised according to an internationally recognised method,15 acted upon and followed up.

Ethics

The local Research Ethics Committee approved the study in June 2009 (09/S1103/21) and local National Health Service Research and Development Management approval was granted.

Method

Participants and setting

Approximately 1400 patients with stroke per annum are diagnosed in the regional health organisation which has three acute stroke wards, three stroke rehabilitation centres and an outpatient neurovascular clinic (NVC).

Inclusion criteria

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of stroke who were either discharged home from an inpatient hospital unit or attended the NVC were included.

Exclusion criteria

Dysphasia (assessed by speech and language therapy) or confusion (assessed by the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score <24) severe enough to prevent patients from understanding the rationale for the study or from giving informed consent

Discharge to long-term nursing care

Terminal illness

Inability to nominate a community pharmacy

Recruitment

Patients due for discharge from acute and rehabilitation stroke units were identified by the ward team who obtained permission from potentially eligible inpatients to be approached by the clinical pharmacist researcher who visited the patient to discuss the study, provide a patient information sheet and obtain consent. Patients with stroke attending the outpatient NVC were identified through the electronic patient management system and posted an invitation letter, patient information sheet and consent form for postal return.

Patients were included from all-care settings as previous work by the research team has shown that all patients with stroke have pharmaceutical care needs.3

Randomisation

Randomisation would be required in a definitive study to compare outcomes between groups. Randomisation to intervention or usual care group was undertaken using sequentially numbered opaque envelopes prepared by an independent person to ensure allocation concealment. Previous work suggests patients living alone have more problems with their medicines.3 Therefore, stratification was applied prior to randomisation to ensure equal numbers of living alone in each group. The researcher and wider healthcare team were not blinded to the treatment arm of the study.

Data collection and intervention

The intervention tool was designed from previous work3 16 17 and includes a pharmaceutical care plan and individualised patient information sheet (see online supplementary appendix 1). To populate the intervention tool, the clinical pharmacist researcher collected data from clinical records and from patient interview while in hospital (inpatients) or at the 1 month visit (NVC outpatients). The following data were collected:

BP and cholesterol measurements

Current medication

Lifestyle records (smoking, diet, alcohol, physical exercise)

Social and practical support (eg, difficulty in organising repeat prescriptions, physically taking medicines)

MMSE

An assessment was made of current medication against stroke evidence-based guidelines for secondary prevention taking into account comorbidities and the need for additional therapy. Suitability of doses and medication type was assessed for the individual taking into account medicine interactions, renal and liver function, comorbidities and potential side effects. Medicines were also assessed for suitability of formulation and medicine device in relation to physical abilities of patients with stroke. Pharmaceutical care issues (ie, problems or potential problems) were identified by the clinical pharmacist researcher, were recorded on the tool and were followed up with the most appropriate member of the MDT.

A copy of the individualised patient information sheet was provided to patients after the interview and the intervention tool was sent to the patient's GP and nominated Community Pharmacy.

At 1, 3 and 6 months after discharge or outpatient NVC visit, the clinical pharmacist researcher visited each patient in their own home to identify additional issues which may have arisen since last visit and resolve outstanding issues which had not been satisfactorily concluded.

These time points were selected as it is known that non-adherence occurs more often with new than existing medicines;18 a US study has shown that 25% of 2888 patients discontinued one or more stroke medicines 3 months post-discharge19 and adherence declines substantially after the first 6 months of treatment.20 Prior to each home visit, the clinical pharmacist researcher visited the patient's GP practice to update the intervention tool with relevant data, for example, medicine changes and BP results. Following each home visit, a letter was sent to the GP and community pharmacist recording issues and recommended actions where appropriate with an invitation to discuss with the clinical pharmacist researcher if required.

All patients were posted a questionnaire for self-completion after the 6-month home visit for return in a stamped addressed envelope to another member of the research team blinded to treatment allocation. Quality of life using the Euroquol-5D, a questionnaire previously used in patients with stroke, adherence (Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS)), medicine beliefs (Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire) and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD)) were measures included in the questionnaire.21–24 A patient satisfaction section used a modified version of a validated satisfaction questionnaire and included additional questions for the intervention group specifically regarding the 1-month and 3-month home visits.25–27 The MMSE was repeated at the 6-month home visit to confirm whether patients’ ability to complete the questionnaire was unchanged. If changed, the patient would be transferred to the usual care group. Pharmaceutical care issues were identified during the clinical medication review process and recorded throughout the study in the intervention group and at the 6-month home visit in both groups. Issues requiring resolution were included in a letter to the GP for both groups.

BP and cholesterol measurements were accessed at the time of the 6-month home visit and the proportion of patients meeting targets was compared.

The clinical pharmacist researcher measured the BP in the intervention group at each home visit and in the usual care group at the 6-month home visit. All patients were required to attend a short clinic appointment at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (WTCRF) at 6 months for assessment of outcomes (BP, self-reported adherence and patient knowledge questionnaire) by independent nurses blinded to randomisation to minimise potential bias. Patients who were unable to attend the WTCRF clinic were visited by nurses in their own home.

Usual care

Patients were discharged from all settings following standard procedures. This group received one home visit at 6 months to collect comparison data with the intervention group. Ability to provide a clinical pharmacy service to inpatients may have affected the level of pharmaceutical advice the usual care group received prior to discharge.

Results

Recruitment process

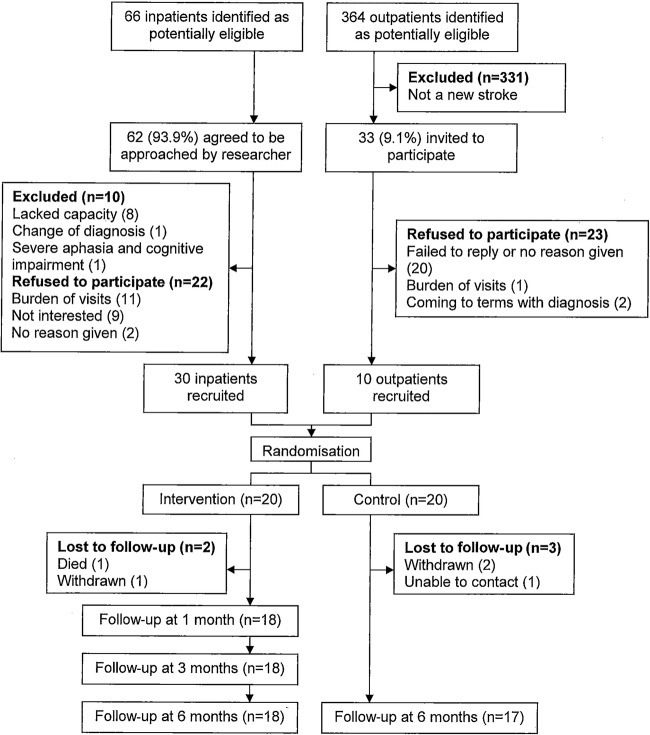

Of the 66 inpatients and 364 NVC outpatients identified as being potentially eligible for inclusion, 331 outpatients were excluded on the basis of having a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or diagnosis other than stroke and four inpatients did not agree to be approached by the researcher. Of the 95 invited to participate, 10 inpatients were excluded, 45 declined, resulting in 30 inpatients and 10 NVC outpatients being randomised. A total of 18 patients in the intervention group and 17 in the usual care group completed the study as 5 were lost to follow-up (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the study enrolment, allocation and follow-up.

Recruitment occurred between July and November and participants were followed up over the following 6 months. The two groups were similar demographically (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics*

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n=18) | Control group (n=17) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 74.2 (8.8) | 71.9 (7.3) | 0.401 |

| Sex, female (%) | 9 (50.0) | 5 (29.4) | 0.305 |

| Living alone (%) | 4 (22.2) | 5 (29.4) | 0.711 |

| Type of stroke (%) | |||

| Lacunar anterior | 5 (27.8) | 6 (35.3) | 0.725 |

| Partial anterior | 9 (50.0) | 7 (41.2) | 0.854 |

| Partial occipital | 0 | 3 (17.6) | 0.104 |

| Total anterior | 3 (16.7) | 1 (5.9) | 0.603 |

| Intracerebral Haemorrhage | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 1.000 |

| History of stroke care setting at recruitment (%) | |||

| Acute stroke unit only | 6 (33.3) | 7 (41.1) | 0.897 |

| Acute stroke and rehabilitation unit | 7 (38.9) | 6 (35.3) | 0.826 |

| Neurovascular outpatient clinic | 5 (27.8) | 4 (23.5) | 0.706 |

| Mean systolic BP mm Hg (SD) | 140.7 (21.8) | 128.5 (19.6) | 0.087 |

| Mean diastolic BP mm Hg (SD) | 78.4 (12.7) | 72.5 (8.4) | 0.057 |

| BP ≤140/85 mm Hg (diabetes 130/80 mm Hg) | 6 (33.3) | 9 (52.9) | 0.407 |

| Mean total cholesterol mmol/L (SD) | 4.4 (1.2) | 4.4 (1.1) | |

| Baseline cholesterol ≤5 mmol/L (%) | 11 (61.1) | 13 (76.5) | 0.471 |

| Community pharmacy medicines provision | |||

| Patient collects | 7 (38.9) | 9 (52.9) | 0.621 |

| Carer collects | 4 (22.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0.658 |

| Pharmacy delivers | 7 (38.9) | 6 (35.3) | 0.826 |

*Numbers of patients unless otherwise stated.

BP, blood pressure.

Data collection process

The hospital and GP practice patient record systems were accessible for all participants.

At recruitment, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) measurements were unavailable in 5 and 27 patients, respectively, resulting in clinical and prescribing data being available for only 8 patients (23%).

During the 6-month study period, complete sets of clinical and prescribing data were available for 16 of 35 patients (46%). For one patient in the usual care group, not a single BP measurement was recorded. Monitoring of cholesterol and LDL was not undertaken for 7 and 19 patients, respectively.

About 90% of questionnaires were returned. Completion rates for the questionnaires are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Questionnaire completion rates, n (%)

| Questionnaire | Intervention (n=18) | Usual care (n=17) |

|---|---|---|

| BMQ | 16 (88.9) | 15 (88.2) |

| Perception of benefit | 16 (88.9) | 15 (88.2) |

| MARS | 16 (88.9) | 11 (64.7) |

| Euroqol-5D | 16 (88.9) | 14 (82.4) |

| Euroqol thermometer | 17 (94.4) | 14 (82.4) |

| HAD | 17 (94.4) | 11 (64.7) |

| Satisfaction | 14 (77.8) | 13 (76.5) |

BMQ, Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire; HAD, Hospital Anxiety and Depression; MARS, Medication Adherence Rating Scale.

BP process

In the intervention group, intra-individual patient BP measurements varied irregularly at 1, 3 and 6 months. There was also variation between the researcher measurements in the home setting and the nurse measurements in the home setting or the clinic. At the 6-month follow-up, the mean (SD) number of BP measurements per patient taken in primary care was 2.2 (1.0) for the intervention group and 1.9 (1.7) for the usual care group. One patient had no BP measurements recorded. Five participants opted to have the WTCRF visit in their own home.

Pharmaceutical care

The total number of care issues identified in the intervention group was 104 (mean 5.8 (2.1), per patient, range 3–10) which fell into the following categories:17 additional medicine (n=10), unnecessary medicine (n=1), wrong medicine (n=1), dose too low (n=5), adverse drug reaction (n=11), interaction (n=8), inappropriate compliance (n=18) and monitoring and patient advice (n=50). Monitoring included recommendations for checking records for laboratory tests, INR and BP measurements. Written and verbal information were provided about medicines and lifestyle behaviours. Pharmaceutical care issues identified from observation of medicine-taking behaviour in patients own homes included a patient taking two brands of the same antihypertensive medicines, doses remaining in medication compliance aids, stockpiling medicine, use of expired medicines and dispensing errors.

In the intervention group, 23 recommendations were made to GPs, of which 19 (83%) were accepted (box 1).

Box 1. Pharmaceutical care recommendations to general practitioner (n=23).

Additional drug required

▸ Calcium/vitamin D recommended in two patients with osteoporosis

▸ Proton pump inhibitor recommended for aspirin-associated dyspepsia

▸ Additional antihypertensive recommended for five patients*

Unnecessary drug

▸ Recommended to stop dipyridamole as warfarin was started

Wrong drug

▸ Recommended changing dipyridamole to licenced modified release formulation

Dosage too low

▸ Recommended increasing dose of levothyroxine based on thyroid function tests

▸ Recommended titrating dose of antihypertensive in two patients

Adverse drug reaction

▸ Recommended discontinuing dipyridamole in a patient experiencing headache

▸ Recommended increasing to indicated dose of proton pump inhibitor for gastrointestinal prophylaxis

▸ Recommended discontinuing tamsulosin in patient with postural hypotension

▸ Recommended monitoring potassium in patient with hyperkalaemia who were recently started with spironolactone†

▸ Recommended check of creatine kinase in suspected statin-induced myopathy

Interaction

▸ Recommended change of statin in a patient who was prescribed simvastatin and carbamazepine

Inappropriate compliance

▸ Recommended including warfarin in multicompartment compliance aid following risk assessment

Other

▸ Recommended malnourished patient to be referred to a dietician†

▸ Recommended patient with high HbA1c to be referred to a diabetes clinic

▸ Recommended follow-up of blood pressure following isolated high result

*Recommendation not accepted in two patients.

†Recommendation not accepted.

Discussion

Strengths and weaknesses

No data were available from non-respondents which could limit generalisability.

One single researcher may not reflect practice which could influence the generalisability but a strength was that the researcher was a clinical pharmacist and the intention is that the intervention would be delivered by a qualified prescribing pharmacist.

Recruitment

The proportion of patients attending the NVC with a diagnosis of new stroke was small (9.1%) and only a third of those eligible consented to participate compared with two-thirds in the inpatient group. There is potential to increase eligibility by including those with confirmed diagnosis of TIA in addition to stroke, as issues are similar.

Higher recruitment of inpatients may have been influenced by personal contact with the researcher allowing the opportunity for questions and clarification. A similar method should be used for NVC outpatient recruitment in a definitive RCT as opposed to the postal method used in this study. This may also elucidate why patients refused to participate as most (22/45) failed to give a reason or reply.

Consideration should be given to screening patients at the first visit to identify those with greater pharmaceutical care needs to determine whether a second face-to-face visit is necessary. Recruitment may be unaffected but the intervention may be more efficient.

Consideration should be given to further stratify patients according to complexity of pharmaceutical care needs. This would require to be taken into account when calculating the sample size for a future study.

Data collection

Data collection from hospital and GP practices was straightforward but electronic transfer methods should be explored to reduce the need for GP practice visits.

Lack of GP measurement of total and LDL cholesterol was the main reason for the low percentage of available data. The rate was too low for meaningful analysis. Given this and the evidence that stroke secondary prevention should include cholesterol-lowering agents irrespective of blood total cholesterol,1 cholesterol measurement would be excluded from a definitive RCT as it would not be a meaningful outcome measure.

Questionnaires were distributed by post and, given the attrition rate to be 10%, this method is acceptable. Overall completion rate did not meet the set criterion and was less in the usual care group, possibly due to less researcher contact and was lowest for the MARS and HAD sections. It would be desirable to review the content and explore a shorter version of the questionnaire.

Blood pressure

The frequency of routinely collected BP measurements from GP records was insufficient for use as an outcome measure in a future study. The intra-individual variation observed in single BP measurements taken by the clinical pharmacist researcher and research nurses suggests that a more reliable method of BP measurement is required if BP is to be used as a future measure of effect of an intervention. Although ambulatory BP monitoring is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for the accurate diagnosis of hypertension, it may be burdensome for patients. Other studies12 28 have taken multiple readings, have brought patients to clinics or used home BP monitors, which are also burdensome. There is a need to further test for patient acceptability to estimate size of effect for future power calculations. A future study could not rely on routinely recorded BP measurements by primary care clinicians. BP measurements are required to be taken by investigators as part of a definitive RCT.

Pharmaceutical care

Communication of care issues with GPs was by letter and although there was high acceptance of recommendations, it would be desirable to align with local emerging e-communication and paperlite methods.

The nature of the identified pharmaceutical care issues (box 1) supports the benefit from a pharmacist-delivered intervention. Although home visits allowed identification of issues that otherwise would not be identified, telephone contact should be considered as an option for follow-up consultations. An RCT published in abstract form only showed that pharmacists providing telephone follow-up to 30 patients with stroke versus usual care improved adherence to secondary prevention medicines (anti-thrombotics specifically) and achieved BP, lipid level and glucose control goals—an effect sustained up to 1 year.11

A prescribing pharmacist delivering the intervention in the main study has the potential to reduce the reliance on the GP to make changes and is in line with the current Scottish Government vision as set out in the ‘Prescription for Excellence’ document.29 This is supported by a recent RCT which found that a prescribing pharmacist increased the proportion of patients with TIA or minor stroke reaching target BP and LDL levels compared with nurses reporting results to primary care physicians.28

A pharmacist-led intervention targeting medicine needs of patients with stroke in their own homes would concur with the LoTS care trial recommendations of providing a specialised bespoke service.30

Usual care

There were no differences in feasibility of data collection or questionnaire completion rates in the usual care group as compared with the intervention group. The contamination risk from interventions made by community pharmacists and other MDT members is unknown but the risk is similar for both intervention and usual care groups.

Conclusion

This study highlighted that, before designing a definitive RCT, the following needs to be considered: modification of the recruitment and invitation process and inclusion of patients with TIA to increase eligibility and participation; removal of cholesterol measurements as a meaningful outcome measure; a reliable BP-monitoring process and further qualitative analysis to improve questionnaire completion rates.

This pilot study tested the feasibility of a number of processes. Findings suggest that there is a need for further feasibility testing of the process of BP monitoring and its acceptability to patients as this is the proposed outcome for the definitive RCT.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject?

Recurrent stroke accounts for approximately 25% of all strokes.

Systematic reviews of complex interventions in stroke conclude that few have been adequately developed or evaluated.

There is scope for pharmaceutical care to optimise stroke secondary prevention.

What this study adds?

Consider inclusion of patients with transient ischaemic attack to improve recruitment rate. Face-to-face invitation to participate is more successful than postal invitation.

If blood pressure is to be used as an outcome, a reliable process for measurement is required.

Although questionnaire return rate was acceptable, reasons for lower completion rates require investigation.

Iterative feasibility testing is necessary to inform a randomised controlled trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients and carers and the nurses of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility for their participation in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by the Chief Scientist Office as part of the NHS Health Services Research Programme (HSRP006).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The local Research Ethics Committee (09/S1103/21) and local National Health Service Research and Development Management approval was granted.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of patients with stroke or TIA: assessment, investigation, immediate management and secondary prevention. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Stroke Organisation. Guidelines for Management of Ischaemic Stroke 2008. www.eso-stroke.org/eso-stroke/education/guidelines.html

- 3.Souter C, Kinnear A, Kinnear M, et al. . Optimisation of secondary prevention of stroke: a qualitative study of stroke patients’ beliefs, concerns and difficulties with their medicines. Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22:424–32. 10.1111/ijpp.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers JA, O'Carroll RE, Hamilton B, et al. . Adherence to medication in stroke survivors: a qualitative comparison of low and high adherers. Br J Health Psychol 2011;16:592–609. 10.1348/2044-8287.002000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakam DG, Spence JD. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: a quantitative modelling study. Stroke 2007;38:1881–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bushnell CD, Olson DM, Zhao X, et al. . Secondary prevention medication persistence and adherence 1 year after stroke. Neurology 2011;77:1182–90. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hankey GJ. Secondary stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:178–94. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70255-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGowan N, Cockburn A, Strachan MWJ, et al. . Initial and sustained cardiovascular risk reduction in a pharmacist-led diabetes cardiovascular risk clinic. Br J Diab Vasc Dis 2008;8:34–8. 10.1177/14746514080080010801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Simoni A, Hardeman W, Mant J, et al. Trials to improve blood pressure through adherence to antihypertensives in stroke/TIA: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000251, 10.1161/JAHA.113.000251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chui CC, Wu SS, Lee Py, et al. . Control of modifiable risk factors in ischaemic stroke outpatients by pharmacist intervention: an equal allocation stratified randomised study. J Clin Pharm Ther 2008;33:529–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen V-HV, Poon J, Tokuda L, et al. . Pharmacist telephone interventions improve adherence to stroke preventive medications and reduce stroke risk factors: a randomized controlled trial Stroke 2011;42:e244. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lager KE, Mistri AK, Khunti K, et al. . Interventions for improving modifiable risk factor control in the secondary prevention of stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(5):CD009103 10.1002/14651858.CD009103.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redfern J, McKevitt C, Wolfe CD. Development of complex interventions in stroke care: a systematic review. Stroke 2006;37:2410–19. 10.1161/01.STR.0000237097.00342.a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical Research Council Complex Interventions Guidance 2008. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance (accessed 8 Jun 2014).

- 15.Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice. The clinician's guide. 2nd edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004, 178–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palenzuela E, Kinnear A, Kinnear M. Adherence to prescribing guidelines and design of a pharmaceutical care plan for stroke patients. Pharm World Sci 2009;31:54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souter C, Kinnear A, Kinnear M. Primary care audit of prescribing adherence to stroke guidelines in patients discharged from an acute stroke unit. Int J Pharm Pract 2009;17(Supp1):A34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber N, Parsons J, Clifford S, et al. . Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:172–5. 10.1136/qhc.13.3.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bushnell CD, Zimmer LO, Pan W, et al. . Persistence with stroke prevention medications 3 months after hospitalisation. Arch Neurol 2010;67:1456–63. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. New Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97. 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorman PJ, Waddell FM, Slattery J, et al. . Is the Euroqol a valid measure of health-related quality of life after stroke? Stroke 1997;28:1876–82. 10.1161/01.STR.28.10.1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res 2000;42:241–7. 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24. 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krass I, Delaney C, Glaubitz S, et al. . Measuring patient satisfaction with diabetes disease state management services in community pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm 2009;5:31–9. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker R. Development of a questionnaire to assess patients’ satisfaction with consultations in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1990;40:487–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart DC, George J, Bond CM, et al. . Exploring patients’ perspectives of pharmacist supplementary prescribing in Scotland. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:892–7. 10.1007/s11096-008-9248-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, et al. . Case Management for blood pressure and lipid level control after minor stroke: PREVENTION randomised controlled trial. CMAJ 2014;186:577–84. 10.1503/cmaj.140053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prescription for Excellence: A Vision and Action Plan for the Right Pharmaceutical Care through Integrated Partnerships and Innovation. Scottish Government Edinburgh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forster A, Mellish K, Farrin A, et al. . Development and evaluation of tools and an intervention to improve patient- and carer-centred outcomes in Longer-Term Stroke care and exploration of adjustment post stroke: the LoTS care research programme. Programme Grants Appl Res 2014;2:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2016-000918supp001.pdf (284.3KB, pdf)