Abstract

Objectives:

Trends over time in the United States show success in rebalancing long-term services and supports (LTSS) towards increased home and community-based services (HCBS) relative to institutionalized care. However, the diffusion and utilization of HCBS may be inequitable across rural and urban residents. We sought to identify potential disparities in rural HCBS access and utilization, and to elucidate factors associated with these disparities.

Design:

We used qualitative interviews with key informants to explore and identify potential disparities and their associated supply-side factors.

Setting and participants:

We interviewed three groups of healthcare stakeholders (Medicaid administrators, service agency managers and staff, and patient advocates) from 14 states (n = 40).

Measures:

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, and data were thematically coded using a standardized codebook.

Results:

Stakeholders identified supply-side factors inhibiting rural HCBS access, including limited availability of LTSS providers, inadequate transportation services, telecommunications barriers, threats to business viability, and challenges to caregiving workforce recruitment and retention. Stakeholders perceived that rural persons have a greater reliance on informal caregiving supports, either as a cultural preference or as compensation for the dearth of HCBS.

Conclusions and implications:

LTSS rebalancing efforts that limit the institutional LTSS safety net may have unintended consequences in rural contexts if they do not account for supply-side barriers to HCBS. We identified supply-side factors that 1) inhibit beneficiaries’ access to HCBS, 2) affect the adequacy and continuity of HCBS, and 3) potentially impact long-term business viability for HCBS providers. Spatial isolation of beneficiaries may contribute to a perceived lack of demand, and reduce chances of funding for new services. Addressing these problems requires stakeholder collaboration and comprehensive policy approaches with attention to rural infrastructure.

Keywords: rural, health care access, home and community based services, long-term services and supports, rebalancing, Medicaid

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, state and federal initiatives have aimed to reduce use of institutional long-term services and supports (LTSS), such as nursing homes, through the increased use of home and community based services (HCBS).1-6 The recent Balancing Incentive Program (BIP) sought to facilitate increased use of HCBS among states spending less than 50% of Medicaid LTSS funds on HCBS. Such “rebalancing” efforts reflect consumer preferences for HCBS over institutional care3,7-10 and may facilitate community integration of beneficiaries in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Olmstead decision.11 Because HCBS is generally less costly than institutional forms of LTSS, rebalancing may also offer potential cost-savings for state Medicaid agencies12 as well as beneficiaries and their families.13

However, given well-recognized differences between urban and rural areas in access to medical care,14,15 LTSS rebalancing efforts may face similar challenges ensuring access and result in inequitable impacts across rural and urban environments. There is a dearth of literature examining potential HCBS disparities in the context of rebalancing policy efforts such as BIP. Rebalancing may have unintended consequences if implemented amidst baseline inequities in health and in non-institutional LTSS availability, access, and quality for rural populations. For example, as non-Hispanic white older adults decreased use of nursing homes and shifted toward increased use of HCBS between 1998-2008, the proportion of racial and ethnic minority older adults in nursing homes grew.3 Additionally, recent analyses found that in rural areas, nursing home closures occurred despite limited availability of HCBS services in their stead.16

Medical care access disparities have been attributed to structural factors, such as limited transportation infrastructure, distances separating providers and patients, and provider shortages.15,17-19 In tandem with these medical care barriers, rural populations tend to be older, poorer, and fare worse on numerous health indicators compared to urban residents.20,21 Poorer health and greater physical and functional limitations1,20,22-24 place rural persons at increased risk for unmet HCBS needs when compared to their urban counterparts.

Research on potential rural disparities in HCBS is pressing, given the attention to rebalancing LTSS and the growth of the older adult population in rural regions.2 Because rebalancing efforts seek to shift the supply and availability of health care (in this case, HCBS in place of institutional LTSS), our analysis was informed by a multilevel framework focused on health care access and the structural factors that might exacerbate disparities, rather than a focus on the individual-level factors that predominate in health care disparities literature generally.25-27 Specifically, we applied a supply-side framework developed by Levesque et al.28 This framework synthesizes several decades of research regarding dimensions of health care access, and distills these perspectives into five distinct but interrelated domains. In this framework, approachability reflects concepts such as informational access, acceptability reflects the cultural and social acceptability of the services, availability and accommodation reflects the presence of services and also the pragmatics of accessing these services, affordability reflects the financial accessibility of services, and appropriateness reflects the concordance between services and needs, as well as adequacy and continuity of these services.28

METHODS

We examined the potential for rural-urban disparities in HCBS access, drawing from qualitative interviews in a larger mixed-method study of BIP implementation and impacts on HCBS access and utilization. A key component of these interviews was a formative assessment of stakeholders’ perceptions of the LTSS and HCBS landscape in their states, inclusive of states that did and did not participate in BIP. These data were used for the present analyses.

Sample.

We conducted 40 interviews with key informants from 14 states that were eligible to apply for BIP (eight BIP-participating states and six BIP non-participating states). Interviews were stratified into three key informant types: state Medicaid administrators (n=13), service agency staff (including managers and direct service providers; n=14), and patient advocates (n=13). Recruitment was initiated with a letter to state Medicaid Directors requesting permission to contact staff for an interview. Service agencies and patient advocates were identified through online professional organization directories, newspaper or other media references to their organizations, summaries from LTSS program meetings hosted by the state, or direct referral from prior interviewees. Interviewees were invited to participate in an interview via email and phone call and received an email confirmation and calendar invitation following agreement to participate.

Interview Procedures.

Telephone interviews were conducted by an interviewer using a semi-structured discussion guide with a note-taker present. As part of a larger effort to inform subsequent quantitative analyses, the interview guide covered a wide range of topics aimed at each of the key stakeholder groups: 1) current state and perceptions of LTSS programs in the state; 2) perceptions of the relative access or availability of HCBS for different geographic and demographic groups; 3) the decision to and process of applying for BIP; 4) barriers and facilitators to BIP implementation; and 5) impacts of BIP and related programs on important outcomes such as patient health and well-being, access/use, cost. Interview questions that specifically elicited information regarding potential rural disparities are included as an Appendix, though the findings we present here reflect a thorough analysis of all interview data relevant to disparities. Interviews were audio-recorded following respondent consent, and eligible respondents received a $100 honorarium for their participation. The study was approved by the institution’s Human Subjects Protection Committee.

Data Coding and Analysis.

All recordings were transcribed verbatim, de-identified, and coded using a standardized codebook. The codebook was developed in two stages: first, we developed a hierarchical coding scheme drawn from the discussion guides and organized by topic area. Next, two coders independently applied this coding scheme to an initial set of five transcripts. These coders subsequently conferred to identify emergent themes and refine the codebook. The codebook was finalized following coder consensus and team review. Each transcript was coded by one researcher. Coders met weekly to discuss progress and questions about code application; areas of disagreement were resolved via consensus. Codes were applied using Dedoose.29 Text excerpts could receive multiple codes, and coders were instructed to include relevant surrounding text when needed for context.

After coding, text excerpts were extracted into a sortable database that permitted filtering by respondent characteristics or hierarchical code. In weekly meetings and three structured debriefings, team members reviewed the extracts to identify key themes, areas of disagreement, thematic trends, and anomalies. Analytic findings and interpretations were developed into a manuscript and reviewed by all members of the qualitative team.

RESULTS

Within the domains of supply-side disparities28, stakeholders identified factors related to approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, and affordability. We did not find notable differences or patterns by stakeholder category in the disparities they perceived, with one exception. Service agency managers and patient advocates raised multiple points regarding limited business viability and worker shortages in rural areas relative to urban areas; fewer Medicaid administrators articulated this point.

Approachability (informational access, knowledge of service availability, health literacy28).

Communications infrastructure.

Stakeholders reported that the communications infrastructure in rural environments was inadequate for communicating and coordinating the availability of HCBS. One patient advocate described the challenge as “just getting the word out to people that the waivers are available, especially in some of our very rural, underserved areas.” This contrasted with one agency manager’s description of “a proliferation of marketing in more suburban areas.”

Stakeholders noted that many rural persons had limited or no access to the internet, where they might learn of HCBS services. This was problematic given shifts toward web-based HCBS infrastructure, including informational outreach, applications for benefits, and locating services. Rural residents might also have limited cellular phone or landline connectivity, restricting their ability to contact distant administrative offices or services. One provider noted a lack of communications infrastructure in tandem with limited technological skills:

“There’s many sections of the state that have little or no internet access. My particular crowd of people that I serve, they don’t have computers. We’re talking people who have next to nothing and they don’t have the ability to access [the internet], let alone the understanding of how to use it. I do think that the state through this process is relying heavily on internet use and online access and [consumers] don’t have the ability to do that.”

This approachability-related challenge dovetailed with limited available services in rural areas (availability and accommodation). One advocate explained that although there was increased advertising of HCBS service availability (i.e., increased approachability), they were wary of promoting a service that was potentially not available in rural areas:

“We’re really working hard to try to let people know these services are out there… but you kind of pull back a little bit, if we’re going to a very rural part of the state. … I don’t want to tell somebody something’s available and come to find out, it’s really not available in their area.”

Acceptability (concordance between available services and what is socially and culturally acceptable to the population served28).

Perceived rural culture and norms.

Stakeholders commented on a rural culture of informal caregiving. For example, one agency manager conjectured that rural persons were constitutionally different (“it seems like the people are hardier”) from suburban or urban persons. This stakeholder speculated that rural persons “don’t ask for help that much, as opposed to maybe in the suburban cities where maybe you’ve got more people working, more double spouses working, and they can’t take care of their parents…“

However, perceptions that rural persons had a cultural preference for informal caregiving also could reflect adaptation to HCBS deficits. Specifically, rural communities may rely on informal caregiving (e.g., provided by families and neighbors) because of gaps in HCBS. This is supported by the remarks of one service agency manager who reported that it was a common perception that rural persons tended to rely on informal supports. The stakeholder further commented, however, that to them it was unclear whether a tendency to use informal supports was a choice or a necessity:

“… [O]ne of the things we’ve heard repeatedly, as well, is folks in rural communities tend to be the same way, as far as using family and using internal sources for the aging in place experience. Whether they’ve had to or chosen to is another matter, I don’t know…“

Availability and accommodation (ability to access services when and where needed, distribution of services28).

Availability of HCBS providers.

Stakeholders reported that caregivers, providers, and specialty care were disparately concentrated in urban/suburban areas and limited in rural areas. One stakeholder commented:

“[T]wo-thirds of our state area really only has less than one-third of our state population. It really is rural. Services are inconsistent when they’re available. Somebody may have to drive 100 miles to see a particular specialist whereas in other areas of the state, those services are much more readily accessible.”

Transportation.

Stakeholders perceived that limited or non-existent transportation in rural areas contributed to rural disparities in HCBS. One Medicaid administrator explained:

“In our urban communities, we have some fairly robust medical and informal transportation resources for an individual, that helps them remain at home and navigate life outside of an institution, that we do not have in rural areas. So I think that probably is one of those things that makes a difference.”

Transportation deficits may further marginalize rural populations, such that their need is not visible to provider agencies or policymakers who allocate resources. One stakeholder’s response demonstrated the paradox of transportation deficits and rural elders’ inability to attend adult day meetings, thereby potentially obscuring the demand for HCBS:

“I don’t know [whether there are rural disparities], to be honest with you… because they don’t come to adult day meetings and [there are] not too many adult day [care centers] in the rural environment of [omitted state name], because of transportation, mainly. Yet, there’s a high proportion of elders in the woods of [state], the rural areas. But I don’t feel like I could answer that properly.”

Availability of informal supports.

As noted in Acceptability, stakeholders reported the perception that rural persons were more likely to endorse informal caregiving, potentially out of necessity. However, social and economic circumstances might limit the availability of informal caregiver supports. In responding to a question about rural differences in HCBS access or utilization, one Medicaid administrator explained the need for informal supports to enable HCBS utilization:

“[I]n a community where we have not fully recovered from the economic downturn, the availability of caregiver support, informal caregiver support, does impact the ability of someone who would prefer to receive their services through [HCBS program name]; or if there is a [HCBS] site in that area, [the ability to] receive their services from [HCBS program] is impacted by the availability of someone to support that individual in-home.”

Affordability (financial capacity for services28).

Business viability and the HCBS workforce.

The availability and accommodation factors that limited access to HCBS for beneficiaries also challenged the affordability of providing HCBS in the rural context – specifically, the recruitment and retention of a caregiving workforce. Stakeholders, particularly service agency managers and patient advocates, perceived that there was insufficient patient volume in rural areas to make the business of HCBS financially viable for agencies or caregivers. Rural geography required paid caregivers to travel long distances to reach individual patients. One patient advocate noted, “it might be more expensive for them just to get somebody to the house, than it is for them once they’re there to provide the service.” This advocate elaborated:

“… [T]here are no provider agencies. Getting somebody to come to your house at $8 an hour when that’s not even going to fill your tank up, when they’re probably driving 50 miles just to get to the house, families are taking that $8 because they don’t have a provider agency. And then on top of that, they’re having to supplement $2 an hour worth of pay, just so that individual can get to the job. … It’s not a living wage for anybody at all.”

A service agency manager pointed out that the same factors negatively impacted the availability of back-up paid caregivers:

“… you don’t have backup staff that can fill in when the [HCBS] caregiver is sick… because there’s not enough hours to go around.”

Patient advocates also reported that due to travel and low wages for HCBS, potential caregiving employees had better employment opportunities in other industries (e.g., retail stores). An advocate framed caregiving as less desirable, in light of the pay and job duties:

“[A national retail chain] is paying $15 an hour as a starting rate for anybody who signs on and works for them. And we’re not paying that for CNAs [certified nursing assistants] who drive their own car and go out and do odd work and are pretty much in someone’s home unsupervised.”

These problems with workforce viability and retention affected the availability of care for beneficiaries. Direct-care workforce shortages meant that patients were sometimes left waiting for services after receiving HCBS approval. As one Medicaid administrator explained:

“[It’s] often a challenge for beneficiaries or sometimes a challenge for beneficiaries of those programs to, even though they’re approved for services, get access to the caregivers or the level of professional caregiver needed to deliver those services.”

Workforce limitations also presented problems for established beneficiaries. Because it was not financially viable for agencies or their employees to have redundant caregivers available, beneficiaries could face gaps in care coverage, or caregiver turnover. For example, one service agency manager explained: “[The] problem is not access to care getting started, [it’s] more access to continuing care.” This manager referenced one client’s experience as an example:

“[A] lady we have served multiple times in the community of [rural community], and we will find a caregiver that is more than willing to go and provide care, but it’s typically 15 to 20 hours a week is all that she requires. … We don’t have another caregiver, because you can’t have multiple caregivers for one client that’s only receiving 15 or 20 hours a week. So, we try to find another … caregiver. If we’re not successful to doing that in a short period of time, they will re-broker to another provider. This lady has been re-brokered so many times, [our agency has] had her three times. Now, who suffers during that? The client.”

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to provide multi-stakeholder insights into rural-urban disparities in access to HCBS in an era of rebalancing efforts. Our analyses sought to examine how supply-side factors manifest in the context of HCBS, and the unique challenges posed by an increasing policy emphasis on HCBS over institutional LTSS. Medicaid administrators, service agency staff, and patient advocates provided system-level perspectives on barriers to rural HCBS, and the types of barriers identified were relatively consistent across stakeholder types.

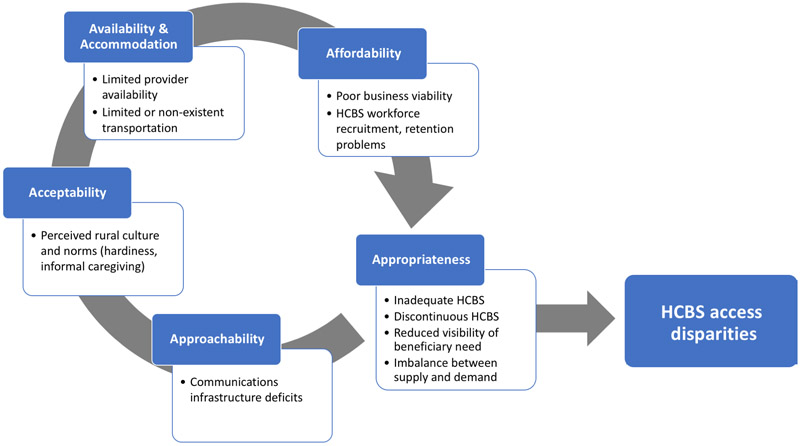

Figure 1 summarizes our findings and presents a revised model of Levesque et al.’s supply-side barriers28 that we adapted to rural HCBS. Approachability manifested as limitations in the communication infrastructure of rural environments, meaning that potential beneficiaries had limited access to HCBS program information and were likely to experience challenges in coordinating care. Availability and Accommodation manifested as limited availability of providers in rural areas and transportation challenges (both distance and lack of transportation services). This had implications for workforce recruitment and retention, especially given the economic context of caregiving employment (e.g., low wages). Acceptability manifested as stakeholders’ perceptions of rural persons’ ‘hardier’ constitutions and cultural inclination to use informal supports, despite the many reasons why these supports might be unavailable to provide consistent care. Affordability manifested as limited business viability and problems with recruiting and retaining an HCBS workforce, due to low reimbursement, dispersed patient need, and long driving distances. As a proximal outcome (Appropriateness, i.e., concordance between demand/need and supply; quality of services), HCBS access was inadequate and discontinuous. There was inhibited visibility of beneficiary need, and an imbalance between HCBS demand and supply. Taken together, these factors contribute to the distal outcome of HCBS access disparities among rural populations.

Figure 1.

Supply-side barriers to HCBS access for rural populations. Framework adapted from Levesque et al.28

We also expanded on the supply-side concept of affordability as originally described by Levesque et al.: “Affordability reflects the economic capacity for people to spend resources and time to use appropriate services.”28 We reframed affordability to more directly reflect a supply-slide (i.e., infrastructure-related) dimension of health care access, and also because Medicaid’s purpose is to make services accessible to persons who otherwise could not afford them. Instead, we posit that HCBS affordability represents the business viability for HCBS care. A revised definition that we propose is “the economic capacity for agencies and providers to spend resources and time to provide appropriate services.”

Stakeholders noted that a lack of transportation and rural geographic expanses contributed to HCBS access disparities. The availability of care may be limited in rural areas, necessitating travel by providers and consumers over long distances.15,19 A particularly insidious effect of transportation barriers is that spatial isolation of beneficiaries can contribute to a perceived lack of demand, which in turn perpetuates lower funding for new services. Telecommunication advances (e.g., the Internet) might ameliorate some of this invisibility and connect providers and policymakers with beneficiaries.15 However, our stakeholders identified limitations in both Internet access and technology literacy.

Similarly, stakeholders indicated that limitations in rural telecommunications likely contributed to HCBS disparities. Given the shift toward electronic platforms for enrollment and coordination in health care more generally, this finding is especially relevant for outreach strategies. Limitations in internet access or technological literacy have implications for dissemination of information about HCBS to potentially-eligible beneficiaries, and for care coordination. This infrastructure limitation, paired with the aforementioned instability and dearth of the rural caregiving workforce, means that beneficiaries and their families are likely to face challenges in accessing HCBS services without additional telecommunications resources or more traditional media outreach (e.g. mailers, radio) in these areas.

Stakeholders also highlighted the limited availability of HCBS providers and caregivers. In the rural environment, where patients are geographically dispersed, workforce conditions such as low wages are likely to have a greater impact on the rural workforce. Factors such as the lower ‘baseline’ availability of care workers in rural areas also have implications for current rebalancing efforts. For example, fewer home health workers in rural regions meant that changes in Medicare policy potentially had a differential and potentially negative impact on rural settings following the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.31 Our stakeholder reports align with research documenting consumers’ beliefs that personal attendants are in short-supply, are underpaid, and that this impacts care worker retention and quality of care.32,33 To facilitate rebalancing efforts, HCBS policymakers may need to address higher wages, better job training, and improved employment trajectories. The need for HCBS continues to grow, given more rapid population aging in rural areas.5,34,35

Relatedly, stakeholders also perceived that transportation problems and dispersed clients meant that providing HCBS was not viable from a business perspective. This parallels previous findings from one state related to disability services and rehabilitation.18 It is also congruent with findings that the availability of assisted living settings is driven primarily by business considerations, and these residences are more available in densely-populated higher-income areas and less available in rural areas.36,37 When these residences do exist in rural settings, they may be unaffordable and offer less privacy or fewer services than those in metropolitan settings.36

Our findings contribute to the growing body of research on rural health disparities. For example, our study elucidates supply-side factors such as limited transportation, lower provider availability, and structural factors that contribute to rural differentials in HCBS access. These are cross-cutting issues for health disparities as well.15,17-19,21 Our analysis contributes to disparities research by documenting administrators’, providers’, and patient advocates’ perspectives. These are less represented in existing literature, which has primarily documented patient and caregiver experiences.

Our findings also have several limitations. First, interviews were conducted within 14 states that were eligible to apply for BIP; findings may not be representative of all states. Our interviews were not designed to make cross-state comparisons in HCBS disparities with regard to BIP versus non-BIP states. However, they provide insight into rural challenges in the context of a large and recent policy initiative (BIP). Additionally, states were ineligible to apply for BIP if their HCBS spending was more than 50% of Medicaid LTSS expenditures;11 the rural landscape of HCBS may be different in states that have already achieved this spending benchmark. Second, while we conducted 40 interviews, these individuals were stratified across three stakeholder types. We do not suggest that these interviews capture the totality of stakeholder perspectives; rather, these perspectives identify pressing areas to consider in future research. Third, because we were focused on supply-side factors, we did not interview HCBS consumers. Rural consumers may have distinct perspectives that are not reflected in our interviews with non-consumer stakeholders. Relatedly, we did not examine disparities across the types of beneficiary needs, though any disparities by chronic condition or functional needs are likely to be further exacerbated for rural populations. Fourth, we did not explicitly differentiate the types of HCBS, and research suggests that there is likely variation in access barriers across HCBS types.38 Finally, we note that the designations of “rural” versus “urban” are social constructs that are not dichotomous and are not operationalized consistently across research studies.21,31,39 Respondents defined rural and urban boundaries subjectively within their own state.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Our findings suggest that rebalancing efforts may have unintended consequences. Groups may not benefit equally3,16 from policy interventions such as BIP if there are barriers to the existence or growth of HCBS. Further, policies emphasizing HCBS over institutional LTSS may have unintended negative effects on rural persons by limiting the institutional LTSS safety net. In examining nursing home closures and potentially disparate impacts in rural environments, Tyler et al.16 draw a cautionary parallel to the era of psychiatric institution closure – because of a lack of community-based services in situ, persons with psychiatric conditions faced potential homelessness after they were deinstitutionalized. If institutional LTSS becomes less available due to rebalancing efforts, rural areas without current HCBS alternatives (and further, with structural barriers that impede the development and growth of HCBS) are likely to suffer. More proximally, efforts to rebalance must account for the social and structural contexts of rural HCBS, or they may inadvertently exacerbate disparities. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive policy approaches with the collaboration of stakeholders (e.g., addressing rural provider shortages, and working conditions for caregivers) to respond to the unique challenges of access to HCBS in rural areas.1

Acknowledgements:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Ammarah Mahmud for her assistance with qualitative coding, and the interviewees for their time and insights.

Funding sources: This research was supported by 1R01MD010360 (PI: Shih).

Appendix. Disparities questions excerpts*

| Interview Topic | Medicaid Admin |

Service Agency Staff |

Patient Advocate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIP | Non -BIP |

BIP | Non -BIP |

BIP | Non -BIP |

|

| I’m particularly interested in any differences that might have existed between groups in access to HCBS or use of HCBS. • Can you describe any differences between groups in terms of their access to or use of HCBS? For example, differences between racial/ethnic groups, or between different communities such as the disability community and the behavior health community? • How about geographic differences, such as between rural vs urban areas? • How about differences related to family structure, e.g. whether a beneficiary has a spouse or children • Are there any other differences among demographic groups in terms of access or utilization of HCBS during the pre-BIP period that you think are important for me to know? |

X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Are some groups in your state more likely than others to use HCBS instead of institutionalized care? If so, why? | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| What are the key factors that determine whether or not someone is able to receive HCBS in your state? • What kinds of things may make it more difficult for people to access HCBS? • What kinds of things may make it easier for people to access HCBS? |

X | X | X | |||

| In what ways has the availability of HCBS (e.g. in certain areas) affected beneficiary utilization? | X | X | X | |||

| What are some ways your agency, or the State has tried to address these disparities in access? What challenges have you faced in trying to address them? • To the extent that access has been improved, to what extent has the system (or your agency) been able to absorb the additional demand or utilization? |

X | X | ||||

| Now that BIP has ended, in what ways would you say access to or use of HCBS has changed? • Earlier, you mentioned some differences in access and use of HCBS between certain groups. In what ways would you say BIP has addressed those differences? • To the extent that access increased, to what extent has the system been able to absorb the additional demand or utilization? |

X | X | X | |||

| Is there anything else that you think is important for us to know? [if BIP: about the implementation or impact of BIP in (state)?] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Because the discussion guides were tailored for BIP vs. non-BIP states, as well as stakeholder type (e.g., Medicaid administrators versus patient advocates), there are 6 versions of the discussion guide. However, the questions that were germane to health disparities were similar across discussion guides (e.g., Are there differences across groups in their access to HCBS in your state?)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coburn AF, Bolda EJ. Rural elders and long-term care. West J Med. 2001;174(3):209–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coburn AF, Griffin E, Thayer D, Croll Z, Ziller E. Are Rural Older Adults Benefiting from Increased State Spending on Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services? Maine: Maine Rural Health Research Center;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Z, Fennell ML, Tyler DA, Clark M, Mor V. The Care Span: Growth of racial and ethnic minorities in US nursing homes driven by demographics and possible disparities in options. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(7):1358–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane RA. Thirty Years of Home- and Community-Based Services: Getting Closer and Closer to Home. Generations. 2012;36(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye HS, Harrington C. Long-term services and supports in the community: toward a research agenda. Disabil Health J. 2015;8(1):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng T, Stone J, Harrington C. Medicaid home and community-based services: how consumer access is restricted by state policies. J Aging Soc Policy. 2015;27(1):21–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):114–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keenan TA. Home and Community Preferences of the 45+ Population. Washington, DC: AARP;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhard SC. Diversion, transition programs target nursing homes' status quo. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirk C Rebalancing Long-Term Care: The Role of the Medicaid HCBS Waiver Program. Washington, DC: National Health Policy Forum;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Balancing Incentive Program. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/balancing/incentive/index.html.

- 12.Kaye HS. Gradual rebalancing of Medicaid long-term services and supports saves money and serves more people, statistical model shows. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6): 1195–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reaves EL, Musumeci M. Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer.: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation,;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAuley WJ, Spector W, Van Nostrand J. Formal home care utilization patterns by rural-urban community residence. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(2):258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyler DA, Fennell ML. Rebalance Without the Balance: A Research Note on the Availability of Community-Based Services in Areas Where Nursing Homes Have Closed. Res Aging. 2017;39(5):597–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson A Delivering Rural Health and Social Services: An Environmental Scan. Tonronto, Canada: Alzheimer Society of Ontario;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black JC, Wheeler N, Tovar M, Webster-Smith D. Understanding the challenges to providing disabilities services and rehabilitation in rural Alaska: where do we go from here? J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2015;14(3-4):222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, Spencer SM, Solovieva T. Perceived Barriers to Health Care Access Among Rural Older Adults: A Qualitative Study. J Rural Health. 2005;21(3):206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report chartbook on rural health care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith KB, Humphreys JS, Wilson MG. Addressing the health disadvantage of rural populations: how does epidemiological evidence inform rural health policies and research? Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(2):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald P, Coburn A, Dwyer S. Expanding Rural Elder Care Options: Models That Work. Proceedings from the 2008 Rural Long Term Care: Access and Options Workshop 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McConnel CE, Zetzman MR. Urban/Rural Differences in Health Service Utilization by Elderly Persons in the United States. J Rural Health. 1993;9(4):270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller KJ, Mackinney AC. Care across the continuum: access to health care services in rural America. J Rural Health. 2006;22(1):43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derose KP, Gresenz CR, Ringel JS. Understanding disparities in health care access--and reducing them--through a focus on public health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1844–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1608–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedoose Version 7, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. [computer program]. Los Angeles, CA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karon SL, Knowles M. What Did We Learn from the Balancing Incentive Program? Public Policy & Aging Report. 2018;28(2):71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAuley WJ, Spector W, Van Nostrand J. Home health care agency staffing patterns before and after the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, by rural and urban location. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grossman BR, Kitchener M, Mullan JT, Harrington C. Paid personal assistance services:an exploratory study of working-age consumers' perspectives. J Aging Soc Policy. 2007;19(3):27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullan JT, Grossman BR, Hernandez M, Wong A, Eversley R, Harrington C. Focus group study of ethnically diverse low-income users of paid personal assistance services. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2009;28(1):24–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowe J, Berkman L, Fried L, et al. Preparing for Better Health and Health Care for an Aging Population. Discussion paper. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Medicine,;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.United States Government Accountability Office. Long-term Care Workforce: Better Information Needed on Nursing Assistants, Home Health Aides, and Other Direct Care Workers. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawes C, Phillips CD, Holan S, Sherman M, Hutchison LL. Assisted Living in Rural America: Results From a National Survey. J Rural Health. 2005;21(2): 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Sizing up the market for assisted living. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H Rural Older Adults' Access Barriers to In-Home and Community-Based Services. Social Work Research. 2006;30(2):109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lichter DT, Ziliak JP. The Rural-Urban Interface: New Patterns of Spatial Interdependence and Inequality in America. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2017;672(1):6–25. [Google Scholar]