Abstract

Background:

Events that instigate disease may involve biochemical events distinct from changes in the steady-state levels of proteins. Even chronic degenerative disorders appear to involve changes such as post-translational modifications.

New method:

We have begun a series of proteomics analyses on proteins that have been fractionated by functional status. Because Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with metabolic perturbations such as Type-2 diabetes, fractionation hinged on binding to phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate (PIP3), key to insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling. We compared mice on normal chow to counterparts subjected to diet-induced obesity (DIO) or to mice expressing human Aβ1–42 from a transgene.

Results:

The prevailing phenotypic finding in either experimental group was loss of PIP3 binding. Of the 1228 proteins that showed valid PIP3 binding in any group of mice, 55% exhibited a significant quantitative difference in the number of spectral counts as a function of DIO, 63% as function of the Aβ transgene, and 79% as a function of either variable. There was remarkable overlap among the proteins altered in the two experimental groups, and pathway analysis indicated effects on proteostasis, apoptosis, and synaptic vesicles.

Comparison with existing methods:

Most proteomics approaches only identify differences in the steady-state levels of proteins. Our overlay of a functional distinction permits new levels of discovery that may achieve novel insights into physiology in an unbiased and inclusive manner.

Conclusions:

Proteomics analyses have revolutionized the discovery phase of biomedical research but are conventionally limited in scope. The creative use of fractionation prior to proteomic discovery is likely to provide important insights into AD and related disorders.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid β-peptide, Western diet, Insulin, Insulin-Like Growth Factor, Phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate, Proteomics, Transgenic mouse

INTRODUCTION

Proteomic comparisons begin with unbiased screening for differentially expressed gene products. Such exploratory studies have greatly advanced discovery in the biological sciences by providing extremely high data content while eliminating the potential for selection bias that is an inherent part of hypothesis testing. Meta-analytic approaches such as gene ontology and pathway-enrichment analyses simplify data interpretation, provide meaningful biological context, and—by amalgamating data from functional or physical categories—can dramatically reduce the frequency of false negatives. However, pathway analysis based solely on differences in steady-state levels of gene products is inherently limited; in addition to changes in quantitative RNA or protein levels most pathways include other events, such as post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and reaction-product feedback. more comprehensive strategy would include the exploration of these and other features. In conjunction with a variable-modification search to identify post-translational modifications, proteomic assessment of the functional state of a protein has the potential to extend unbiased discovery beyond gene expression to create a more comprehensive view of the biochemical response to disease or disease interventions.

Substantial evidence links Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to aberrations in energy metabolism. The prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance in AD patients is much higher (~2-fold) than in age-matched controls (Ohara, 2013). This and other components of metabolic syndrome are often secondary to obesity (Dake and Oltman, 2015; Malafaia et al., 2013; Teodoro et al., 2014), a key risk factor for related age-associated disorders, including type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), which is itself strongly associated with cognitive impairment (Freeman et al., 2014). Although relatively few AD patients are obese, a prior history of obesity is a risk factor for AD (Whitmer et al., 2005), as is high intake of total and saturated fats (Kalmijn et al., 1997). In rodents, diet-induced obesity (DIO)—resulting from feeding either a high-fat or “western” diet (below)— impairs both insulin signaling and mitochondrial functions, which have been implicated in memory loss (Barnard et al., 2014; Petrov et al., 2015; Yuzefovych et al., 2013).

Protein aggregation is a diagnostic feature of all major neurodegenerative diseases, and it is also associated with several metabolic disorders. In addition to aggregation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) and tau, AD pathology includes deficits in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy (Ciechanover and Kwon, 2017; Ihara et al., 2012; Tanaka and Matsuda, 2014). Induction of an unfolded-protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum promotes insulin resistance (Boden et al., 2008; Ozcan et al., 2009). In addition, responses to insulin and leptin are normalized in rat amygdala (Castro et al., 2013) and hypothalamus (Ozcan et al., 2009), respectively, after amelioration of unfolded-protein stress via administration of a chemical chaperone. Damaged mitochondria have been shown to increase protein aggregation in the cytosol (Wang and Chen, 2015); conversely, protein aggregation adds to mitochondrial stress and contributes to neurodegeneration (Sze et al., 2015), in part by disrupting autophagy (Ayyadevara et al., 2015). We have begun to analyze protein aggregates with specialized protocols aimed at discerning distinctions and similarities among these related disorders and their empirical models (Ayyadevara et al., 2015; Ayyadevara et al., 2016b; Parcon et al., 2017).

Proteinopathy may contribute to diseases by interfering with proper transduction of signals initiated by insulin, insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and other factors. Aging is the largest and most significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is associated with numerous changes in signal-transduction pathways (Ayyadevara et al., 2009, Danilovich et al., 2002; Kelly, 2018). Several signaling pathways that are altered with aging are similarly aberrant in AD (De Felice and Ferreira, 2014; Sato et al., 2011). Brains from AD patients show substantially lower expression of receptors for insulin and IGF-1 (Talbot et al., 2012). Related changes in insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) have been described in rodents subjected to DIO (Melnik et al., 2011) and in T2D (Sato et al., 2011), suggesting that altered IIS might underlie the AD-like pathology promoted by both T2D and DIO. Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (abbreviated as PIP3 or PtdIns-P3) is a key component of IIS and other signaling pathways, such as Wnt/frizzled, 5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1; silent mating-type information regulator 2 homolog 1), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors co-activator 1α (PGC-1α). These pathways modulate a number of pathological processes relevant to AD, including production of Aβ, plaque formation, inflammation, mitochondrial metabolism, and metabolic endocrinology. PIP2 is converted by Class-1 phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinases to PIP3, which functions primarily as an inner-leaflet membrane anchor to tether kinases and other signal-transduction proteins.

Here we present a strategy for honing proteomics-based discovery approaches in order to specifically address membrane tethering of signal-transduction proteins in Alzheimer-model mice and in wild-type mice fed a western diet. Instead of simply comparing total proteins on a case-control basis or a treated-versus-untreated basis, we have additionally parsed proteins by their association with membranes. Moreover, we have stratified membrane proteins based on their binding to the key signaling molecule, PIP3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Breeders of the BRI-Aβ42 line (hereafter “Aβ-Tg”) were generously provided by Todd Golde (Univ. Florida, USA). This line carries a transgenic fusion protein that is expressed constitutively in the CNS and cleaved to release Aβ1–42 into the extracellular compartment (McGowan et al., 2005). The line was maintained in a hemizygous state, and comparisons were made between male carriers of the transgene and wild-type littermates. Mice were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle at 23 °C in the AAALAC-certified Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) vivarium. Mice were weaned at ≥25 days of age and housed at a cage density of ≥82 cm2 floor space per mouse. Some males were housed singly due to fighting. Groups were either maintained on their standard diet (LabDiet JL Rat and Mouse/Auto 6F FK67, containing 22%-kcal protein, 16%-kcal fat, and 62%-kcal carbohydrate), or switched to a “western diet” (ENVIGO TD.88137, containing 42%-kcal from fat, 34% sucrose by weight). Both diets were provided ad libitum. At euthanasia, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with heparinized saline to remove blood from the tissues. The brain was quickly removed, and cerebral cortex was dissected and immediately frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use ommittee of the CAVHS.

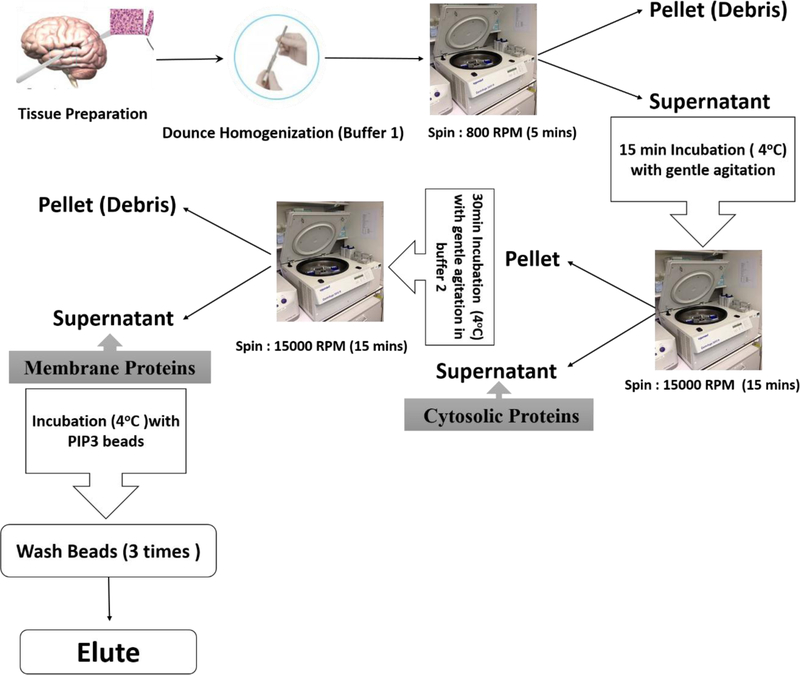

Isolation of membrane proteins

Frozen mouse brain samples (3 per group) were individually pulverized with a dry-ice-cooled mortar and pestle and suspended in buffer with nonionic detergent (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.3 M NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% [v/v] NP40) and protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Millipore-Sigma; Darmstadt, Germany) at 0 °C. Large debris was removed from lysate by brief centrifugation (5 min at 800 rpm). Native membrane-associated proteins were isolated from homogenates with ProteoExtract membrane purification kit (Millipore-Sigma) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Supernatants from these preparations were stored as soluble proteins. Pellets containing membrane-associated proteins were solubilized in either “Buffer 2”—for use in PIP3 binding as described in the next section—or Laemmli buffer [2% SDS (w/v) and 0.3 M β-mercaptoethanol]. The latter were heated 5 min at 95 °C, and electrophoresed on 4–20% polyacrylamide, 1% SDS gels (SDS-PAGE). Gels were stained with SYPRO Ruby (ThermoFisher) to visualize total protein.

Isolation of PIP3-binding membrane proteins

Isolated membrane proteins were precleared with unconjugated agarose beads; the unbound fraction was collected and incubated 6 h at 4 °C with PIP3-conjugated agarose beads (Echelon, Salt Lake City, UT). After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted from PIP3-coated beads, suspended in Laemmli buffer containing 2% SDS (w/v) and 0.3 M β-mercaptoethanol, and heated 5 min at 95 °C prior to separation on 4–20% polyacrylamide/SDS gels as above (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the protocol used for isolation of membrane proteins and the PIP3-binding subfraction of membrane proteins from mouse cerebral cortex.

Identification of membrane- and/or PIP3-binding proteins

Proteins isolated from membranes, or membrane proteins that bind to PIP3-coated beads, were dissolved in Laemmli buffer as described above, and separated in one dimension on 1% SDS, 4–12% acrylamide gradient gels. They were then stained with SYPRO Ruby (Thermo-Fisher) or Coomassie Blue to visualize total protein, and 1-mm slices were excised. Proteins were digested in situ with trypsin, and peptides analyzed by high-resolution LC-MS/MS with a Thermo-Velos Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to a nanoACQUITY liquid chromatography system (Waters, Milford MA) as described previously (Ayyadevara et al., 2016a; Ayyadevara et al., 2016b). Proteins were identified by MASCOT software www.matrixscience.com) matching of peptide fragmentation patterns to a database of previously observed fragment patterns (Ayyadevara et al., 2016a; Ayyadevara et al., 2016b).

C. elegans strains and culture

Wild-type strain Bristol-N2 [DRM stock] and transgenic strain CL4176 (smg-1ts [myo-3/Aβ1–42/long 3´-untranslated region]) were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC). Worms were maintained at 20 °C on plates containing nematode growth medium (NGM) overlaid with E. coli strain OP50 as previously described (Ayyadevara et al., 2009). Strain CL4176 requires an upshift from 20 °C to 25.5 °C at the L3-L4 transition to induce expression ofa human Aβ1–42 transgene. Synchronized cohorts were initiated by lysing worms at day 3 post-hatch (adult day 1) to release unlaid eggs, which were plated on 100-mm Petri dishes as described (Ayyadevara et al., 2009).

RNA interference

Genes that encode PIP3-binding proteins were tested for their roles in protein aggregation and chemotaxis via RNAi knockdown. Worms were fed on gene-targeted bacterial clones from the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath et al., 2003) beginning either at egg hatch or in the mid-L4 larval stage. Synchronized eggs were recovered after alkaline hypochlorite lysis and transferred to plates seeded with HT115 (DE3) bacteria, which are deficient in RNAse III and contain IPTG-inducible T7 RNA polymerase; we used transformants that contained either 1) the L4440 plasmid with a multiple-cloning site (MCS) between two inward-directed T7 RNA polymerase promoters for “feeding vector (FV) controls” or 2) L4440 containing an exonic segment of the targeted gene cloned into its MCS (Kamath et al., 2003). Chemotaxis assays were performed as described previously (Ayyadevara et al., 2015; Dosanjh et al., 2010). Briefly, worms were placed on an agar plate equidistant from n-butanol spotted on one edge and ethanol spotted on the opposite edge. Worms that accumulated near the butanol were counted; the fraction of total is the chemotaxis index (CI).

Results and Discussion

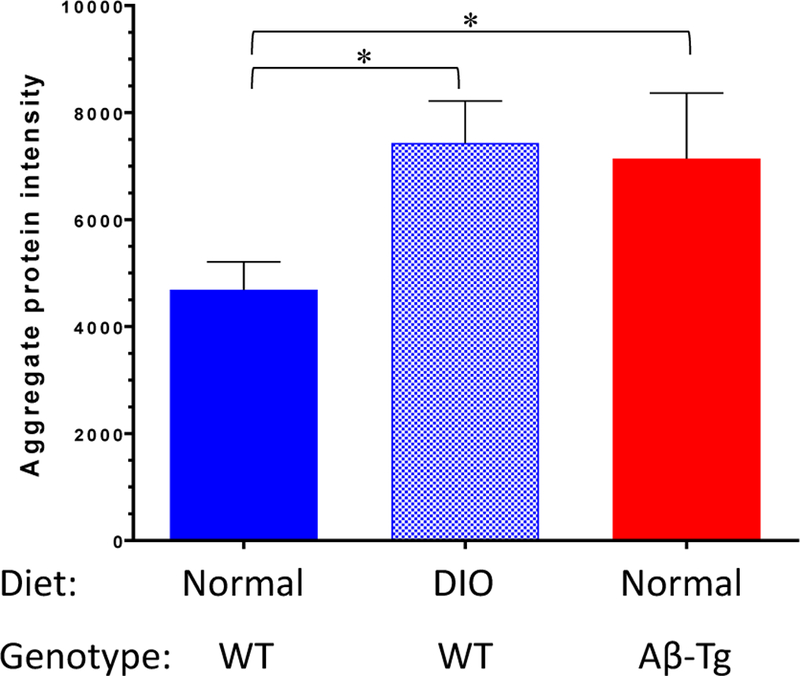

Wild-type mice were fed either their normal diet or were transferred to a “western diet” (high in sucrose and fat) to produce DIO and associated metabolic perturbations. The western diet began at approximately 7 weeks of age and continued until the mice were euthanized at the age of 29 weeks. This paradigm results in DIO and the development of some elements of metabolic syndrome,ACCEPTEDincludinginsulinresistance,hyperinsulinemia, and impaired glucose tolerance. From 7 weeks of differential feeding onward, body weights of the DIO group averaged 11.81±1.82 g (40±5.9%) greater than control mice on normal chow. Quantification of aggregated protein in mouse cerebral cortex indicated that DIO nearly doubled the level of aggregated protein relative to normal diet (Fig. 2). A similar assessment, performed on Aβ-Tg mice, indicated that release of human Aβ1–42 in the brains of these mice was accompanied by elevation of aggregates to the level observed in mice fed western diet, with no additional effect due to diet (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. DIO and Aβ produce greater detergentinsoluble protein aggregation in mouse cerebral cortex.

Sarcosyl-insoluble material was prepared from the cerebral cortex of WT mice fed normal chow, DIO mice, and Aβ-Tg mice fed normal chow. Proteins were resolved on a 4–12% polyacrylamide gradient gel, visualized with SYPRO Ruby, scanned, and quantified. Increases in protein intensity were significant by ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc test (*P <0.05).

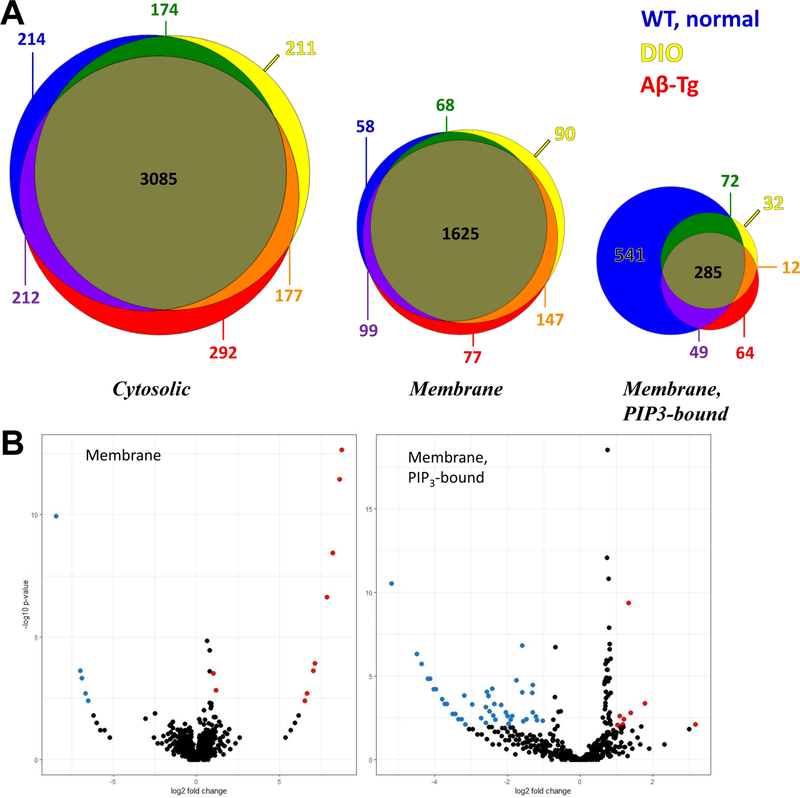

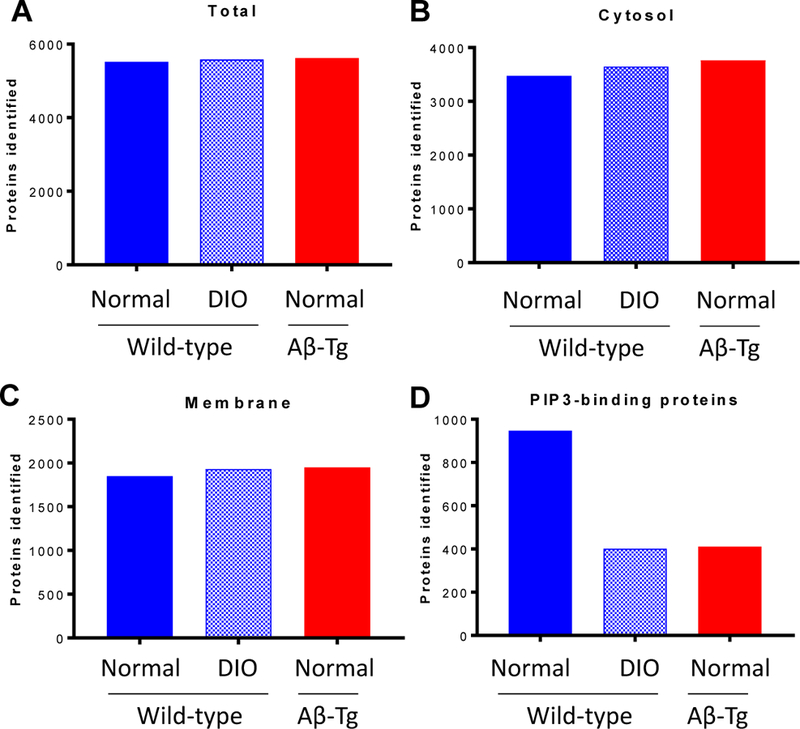

Membrane-associated proteins were isolated from cerebral tissue and further partitioned on the basis of binding to PIP3-coated beads. Three fractions—soluble (mainly comprising cytosolic proteins), membrane-associated, and PIP3-bound membrane proteins—were analyzed by high-resolution LC-MS/MS, and proteins were identified by MASCOT. The total number of proteins identified did not differ among the groups of mice; nor did the count of cytosolic or membrane-associated proteins differ across groups (Fig. 3, A–C). However, the number of unique membrane proteins binding to PIP3 was ~60% lower in DIO or Aβ-Tg mice (Fig. 3D) relative to wild-type mice on a normal diet.

Figure 3. Proteins identified in different fractions showed significant changes only in PIP3-binding membrane proteins.

Tissue homogenates were fractionated as described in Materials and Methods and fractions subjected to proteomic analysis. Numbers of proteins identified in each fraction are depicted for WT mice fed normal diet, DIO, and Aβ-Tg mice on normal diet.

Among the cytosolic proteins, 82–85% are shared by all three experimental groups, with just 16% unique to WT/normal diet, 15% unique to DIO, and 18% specific to Aβ-Tg mice (Fig. 4A). Likewise, 83–88% of membrane proteins are common to all groups, with 12% unique to WT/normal diet, 16% unique to DIO, and 17% unique to Aβ-Tg mice. The subset of membrane proteins that bound to PIP3 beads, however, showed strikingly differential protein profiles. For example, DIO mice lacked 60% of the PIP3-binding membrane proteins identified in mice on a normal diet, while gaining only 8% new proteins; similarly, Aβ-transgenic mice lost 62% of proteins found in wild-type mice and added 14% (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. A: DIO and Aβ alter PIP3-binding membrane proteins.

A: Venn diagrams represent by size of circle the number of proteins in a category. There was an approximately two-fold difference between the total membrane and cytosolic proteins and between the PIP3-bound and membrane proteins. Proteins identified in WT mice fed normal diet are represented by blue (unique to these mice), green (shared with DIO), or purple (shared with Aβ-Tg mice). Proteins identified in DIO are yellow (unique) or orange (shared with Aβ-Tg mice). Proteins identified in uniquely in Aβ-Tg mice are red. Proteins present in all mice are olive-brown. Note the large overlaps present in cytosolic and membrane fractions versus the restriction of PIP3-bound proteins in the DIO mice and the Aβ-transgenic mice. B. Volcano plots of membrane proteins (left) and PIP3-bound membrane proteins (right) in DIO versus WT fed normal chow, p≤0.01 threshold.

Even within the list of PIP3-binding proteins shared by all mouse groups, ~20-fold more proteins were significantly less abundant in DIO than were more abundant in DIO, as illustrated in volcano plots (Fig. 4B) summarizing relative abundances and p-values for individual proteins. Of 1227 membrane proteins showing PIP3 binding in any mouse group, 677 (55%) differed at least 2-fold in spectral counts as a function of DIO, 779 (63%) as function of the Aβ transgene, and 975 (79%) as a function of either variable.

Comparisons of the fractional distribution of individual proteins suggest that redistribution to the cytosol was more common than a reduction in steady-state levels. In the DIO group, only 10 proteins (1.1%) exhibited a ≥2-fold loss in the total number of counts in all fractions. For 67 (14.2%) of the proteins that lost PIP3 binding in the DIO group, each protein’s cytosolic counts increased by at least 70% of the number of counts lost from the PIP3-binding fraction. In the Aβ-Tg mice, 16 proteins (1.8%) showed a substantial loss of in all fractions, and 205 (23.1%) were offset by increased counts in the cytosol.

Several classes of proteins that were altered in their PIP3 binding had been previously implicated in pre-disease and disease states, such as metabolic syndrome, T2D, and AD. In the cerebral cortex of DIO mice, PIP3 binding was completely lost for signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and 3 (STAT1, STAT3) (data not shown). Proteins involved in mitochondrial function, protein clearance and synaptic vesicle formation were also significantly altered by both diet and Aβ expression (data not shown). We are currently engaged in large-scale projects to further confirm differential PIP3 binding for several protein classes and pathways, as well as determine the consequences of their altered participation in insulin/IGF signaling.

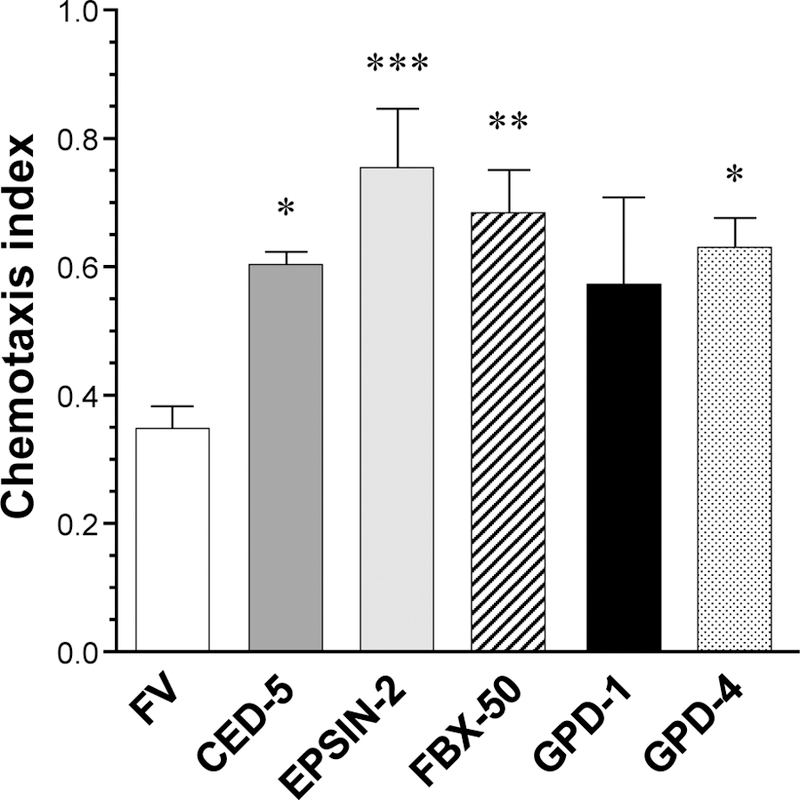

A relatively simple first step to assess the effects of modulating proteins is to alter their expression and assess the impact on a biological system. We began by applying RNAi to reduce expression of proteins that showed elevated PIP3 binding in one or both of our experimental groups (Fig. 5). We utilized a C. elegans model with neuronal expression of a human Aβ1–42 transgene, resulting in Aβ aggregates and correlated neurological deficits, one of which being compromised chemotaxis toward butanol (Ayyadevara et al., 2015). We identified nematode orthologs of several mouse proteins elevated in DIO and/or Aβ-Tg mice: ced-5 (encoding a protein required for phagocytosis), epn-2 (involved in endocytosis), fbxa-50 (F-box proteins linking endocytosis to cullin components of ubiquitin-proteasome system), and gpd-4 (a glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Knockdown of those gene products significantly improved chemotaxis in these Aβ-expressing nematodes, indicating a partial rescue from the neurological deficits associated with Aβ accumulation.

Figure 5. Proteins showing higher PIP3 binding in Aβ-Tg mice impair chemotaxis in C. elegans expressing Aβ.

C. elegans were subjected to an assay of motility toward nbutanol. All worms express Aβ1–42 in neurons and are compromised versus WT, which universally score 1.0. “FV” worms were subjected to empty vector. RNAi knockdown of the indicated genes in other groups improved chemosensory perception as shown by higher chemotaxis indices (*P<0.03, **P<0.004, ***P<0.0005).

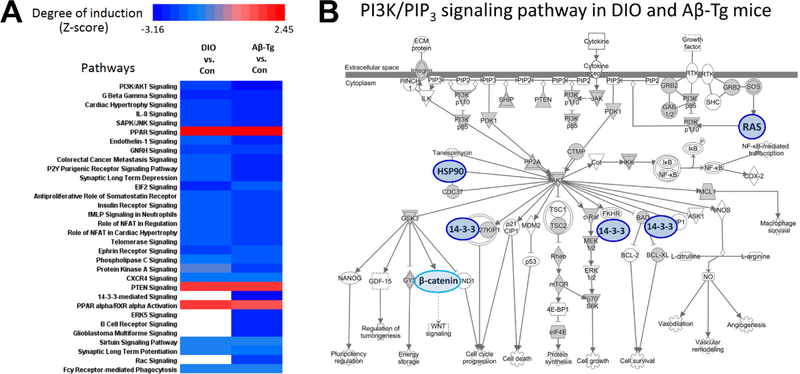

Proteins were also analyzed for enrichment of functional annotations using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) to test for enrichment of pathway and gene-ontology (GO) terms. Within each pathway, a Z score was calculated for either increased or decreased abundance of proteins in DIO or Aβ-Tg mice relative to controls (WT mice on normal diet). Figure 6A summarizes Z scores calculated by Ingenuity™ software and displayed as heat maps. Twenty pathways were significantly downregulated (Z < −2) in both DIO and Aβ-Tg transgenic mice, while only three pathways were upregulated (Z > 2). Not surprisingly, pathways significantly affected in DIO and Aβ-transgenic mice included signaling via PI3K/AKT and the insulin pathway. Within the PI3K/AKT pathway (Fig. 6B) there were significant changes in the cerebral Although modulation of gene expression can contribute to long-term responses to diet or metabolic status, time-critical signals tend to be mediated by more rapid, post-translational processes such as phosphorylation, acylation, ubiquitination, et cetera. In metabolic pathways, enzymes are often modulated by binding of a downstream product (end-product inhibition), and the activities of many multimeric complexes are altered by metabolites or optional protein components, as well as by membrane embedding or tethering. Because the unbiased discovery aspect of proteomics is valuable, the incorporation of functional screening strategies into proteomic analyses provides an important adjunct to screening phenotypic state changes associated with disease, diet, conditioning, or treatment.

Figure 6. DIO or Aβ altered PIP3-binding proteins in discrete signaling pathways.

PIP3-binding proteins from DIO and Aβ-transgenic mice were compared and subjected to pathway analysis. A. A heat map was generated of pathways in which PIP3-binding proteins were significantly altered in DIO (left column) or Aβ-Tg (right column) versus WT mice fed standard chow (“Con”). B. A depiction of the PI3K/PIP3 pathway produced by Ingenuity software was modified to highlight the five proteins (blue) with less binding in both experimental groups; a lower level of PIP3 binding by β-catenin was unique to Aβ-transgenic mice.

We hypothesize that chronic changes in the activity of PI3 kinase, PTEN, or other elements of PIP3 signaling—due to diet or Aβ—produced some of the differences detected. Because a difference in total spectral counts for a given protein was relatively rare, and because the most striking and consistent consequence of the two experimental manipulations was a reduction in PIP3-binding proteins, it appears that most of the differences noted here were due to either 1) a reduction in PIP3 levels or 2) structural changes in the proteins themselves. Regarding the former, a reduction in PIP3 levels was reported in the liver of diabetic rats (Manna and Jain, 2012), but this parameter has not, to our knowledge, been evaluated in the CNS. Although isolation of PIP3-binding proteins required an excess of exogenous PIP3, these proteins had already been selected for membrane association; lower in vivo PIP3 levels would likely prevent many of them from parsing into the initial membrane fraction. Regarding the second possibility, one can easily envisage splicing changes, mRNA editing, or post-translational modifications that would alter a protein’s intrinsic affinity for PIP3. Indeed, we have begun to identify post-translational modifications of some of these proteins which appear to explain their differential fractionation between the two experimental conditions.

It is acknowledged that some proteins detected in the PIP3-binding fraction may partition into this fraction indirectly, as a consequence of binding to other proteins that directly bind PIP3. Another potential source of false-positive results is the loss of normal compartmentalization of proteins during tissue homogenization, which may have allowed access to PIP3 among proteins that are not normally in the same subcellular compartment with this lipid. However, our observation of significant overlap in the PIP3-binding proteins from mice and C. elegans (Ayyadevara et al., 2016a) increases confidence that our methods of detection are appropriate and specific.

False-negative results may obtain due to the fact that some membrane interactions of proteins are weak or transient and may not survive sample preparation. It is reassuring that we identified 88% of the same proteins in a repeat analysis, and most of those were represented by >3 peptides. Moreover, we are currently implementing additional bioinformatics strategies to identify indirect interactions through crosslinking techniques; especially useful are comparisons of crosslinking results before and after binding to PIP3, aggregate isolation, or other fractionations. Indirect associations that occur during or after sample homogenization are potentially artefactual, but these can be revealed by proteomic strategies such as “isotopic differentiation of interactions as random or targeted” (I-DIRT) (Tackett et al., 2005). Despite any remaining limitations, the approach we have outlined here seems useful in identifying robust signal-transduction intermediates, and inclusion of the simple membrane-associated fraction also recovers changes in integral membrane proteins. It is anticipated that such approaches will extend the reach of proteomics research to provide a more complete picture of differences in biochemical pathways.

HIGHLIGHTS.

-

□

Proteomics methodology was used to discover functional differences in proteins

-

□

Wild-type mice on normal chow or “western” diet and Aβ-transgenic mice were used

-

□

Brain proteins were fractionated by binding to phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate

-

□

Most PIP3-binding proteins exhibited lower PIP3 binding in experimental groups

-

□

Functional proteomics suggests loss of PIP3 binding ties Alzheimer’s to diabetes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants P01AG012411 and R01AG062254 from the National Institute on Aging, P20GM103429 from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, and I01 BX001655 from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ayyadevara S, Balasubramaniam M, Gao Y, Yu LR, Alla R, and Shmookler Reis R (2015). Proteins in aggregates functionally impact multiple neurodegenerative disease models by forming proteasome-blocking complexes. Aging Cell 14, 35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadevara S, Balasubramaniam M, Johnson J, Alla R, Mackintosh SG, and Shmookler Reis RJ (2016a). PIP3-binding proteins promote age-dependent protein aggregation and limit survival in C. elegans. Oncotarget 7, 48870–48886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadevara S, Balasubramaniam M, Parcon PA, Barger SW, Griffin WS, Alla R, Tackett AJ, Mackintosh SG, Petricoin E, Zhou W, et al. (2016b). Proteins that mediate protein aggregation and cytotoxicity distinguish Alzheimer’s hippocampus from normal controls. Aging Cell 15, 924–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadevara S, Tazearslan C, Bharill P, Alla R, Siegel E, and Shmookler Reis RJ (2009). Caenorhabditis elegans PI3K mutants reveal novel genes underlying exceptional stress resistance and lifespan. Aging Cell 8, 706–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard ND, Bunner AE, and Agarwal U (2014). Saturated and trans fats and dementia: a systematic review. Neurobiol Aging 35 Suppl 2, S65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G, Duan X, Homko C, Molina EJ, Song W, Perez O, Cheung P, and Merali S (2008). Increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins and genes in adipose tissue of obese, insulin-resistant individuals. Diabetes 57, 2438–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro G, MF CA, Weissmann L, Quaresma PG, Katashima CK, Saad MJ, and Prada PO(2013). Diet-induced obesity induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance in the amygdala of rats. FEBS Open Bio 3, 443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, and Kwon YT (2017). Protein Quality Control by Molecular Chaperones in Neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 11, 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dake BL, and Oltman CL (2015). Cardiovascular, metabolic, and coronary dysfunction in high-fat-fed obesity-resistant/prone rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilovich N, Javeshghani D, Xing W, and Sairam MR (2002). Endocrine alterations and signaling changes associated with declining ovarian function and advanced biological aging in follicle-stimulating hormone receptor haploinsufficient mice. Biol Reprod 67, 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, and Ferreira ST (2014). Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 63, 2262–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosanjh LE, Brown MK, Rao G, Link CD, and Luo Y (2010). Behavioral phenotyping of a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans expressing neuronal amyloid-beta. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LR, Haley-Zitlin V, Rosenberger DS, and Granholm AC (2014). Damaging effects of a high-fat diet to the brain and cognition: a review of proposed mechanisms. Nutr Neurosci 17, 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara Y, Morishima-Kawashima M, and Nixon R (2012). The ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagic-lysosomal system in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn S,Launer LJ,Ott A,Witteman JC, Hofman A, and Breteler MM (1997). Dietary fat intake and the risk of incident dementia in the Rotterdam Study. Ann Neurol 42, 776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421, 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MP (2018). Cyclic nucleotide signaling changes associated with normal aging and age-related diseases of the brain. Cell Signal 42, 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malafaia AB, Nassif PA, Ribas CA, Ariede BL, Sue KN, and Cruz MA (2013). Obesity induction with high fat sucrose in rats. Arq Bras Cir Dig 26 Suppl 1, 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna P, and Jain SK (2012). Decreased hepatic phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) levels and impaired glucose homeostasis in type 1 and type 2 diabetic rats. Cell Physiol Biochem 30, 1363–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnik BC, John SM, and Schmitz G (2011). Over-stimulation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling by western diet may promote diseases of civilization: lessons learnt from laron syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond) 8, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara T (2013). [Glucose tolerance status and risk of dementia in the community: the Hisayama study]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 115, 90–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan L, Ergin AS, Lu A, Chung J, Sarkar S, Nie D, Myers MG Jr., and Ozcan U (2009). Endoplasmic reticulum stress plays a central role in development of leptin resistance. Cell Metab 9, 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcon PA, Balasubramaniam M, Ayyadevara S, Jones RA, Liu L, Shmookler Reis RJ, Barger SW, Mrak RE, and Griffin WST (2017). Apolipoprotein E4 inhibits autophagy gene products through direct, specific binding to CLEAR motifs. Alzheimers Dement [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Petrov D, Pedros I, Artiach G, Sureda FX, Barroso E, Pallas M, Casadesus G, Beas-Zarate C, Carro E, Ferrer I, et al. (2015). High-fat diet-induced deregulation of hippocampal insulin signaling and mitochondrial homeostasis deficiences contribute to Alzheimer disease pathology in rodents. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852, 1687–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Takeda S, Uchio-Yamada K, Ueda H, Fujisawa T, Rakugi H, and Morishita R (2011). Role of insulin signaling in the interaction between Alzheimer disease and diabetes mellitus: a missing link to therapeutic potential. Curr Aging Sci 4, 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze CI, Kuo YM, Hsu LJ, Fu TF, Chiang MF, Chang JY, and Chang NS (2015). A cascade of protein aggregation bombards mitochondria for neurodegeneration and apoptosis under WWOX deficiency. Cell Death Dis 6, e1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett AJ, DeGrasse JA, Sekedat MD, Oeffinger M, Rout MP, and Chait BT (2005). I-DIRT, a general method for distinguishing between specific and nonspecific protein interactions. J Proteome Res 4, 1752–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Wang HY, Kazi H, Han LY, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, Fuino RL, Kawaguchi KR, Samoyedny AJ, Wilson RS, et al. (2012). Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest 122, 1316–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, and Matsuda N (2014). Proteostasis and neurodegeneration: the roles of proteasomal degradation and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843, 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro JS, Varela AT, Rolo AP, and Palmeira M (2014). High-fat and obesogenic diets: current and future strategies to fight obesity and diabetes. Genes Nutr 9, 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, and Chen XJ (2015). A cytosolic network suppressing mitochondria-mediated proteostatic stress and cell death. Nature 524, 481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Barrett-Connor E, Quesenberry CP Jr., and Yaffe K (2005). Obesity in middle age and future risk of dementia: a 27 year longitudinal population based study. BMJ 330, 1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzefovych LV, Musiyenko SI, Wilson GL, and Rachek LI (2013). Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction, and oxidative stress are associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress, protein degradation and apoptosis in high fat diet-induced insulin resistance mice. PLoS One 8, e54059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]