Abstract

Background

Microtus genus is one of the experimental animals showing unique characteristics, and some species have been used as various research models. In order to advance the utilization of Microtus genus, the development of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) is a key point. This review introduces recent progress in the development of ARTs for Microtus genus, especially Microtus montebelli (Japanese field vole).

Methods

Based on previous and our publications, current status of the development of ARTs was summarized.

Results

In M. montebelli, ARTs, such as superovulation, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, embryo transfer, sperm cryopreservation, and nonsurgical artificial insemination, have considerably been established by using the procedures which were originally devised for mice and partly modified. However, when the methods for M. montebelli were applied to Microtus arvalis and Microtus rossiaemeridionalis, all protocols of ARTs except for sperm cryopreservation were technologically invalid.

Conclusion

Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) are considerably established in M. montebelli, and this fact allows this species to be potentially useful as a model animal. However, since ART protocols of M. montebelli are mostly invalid for other species of the Microtus genus, it is necessary to improve them specifically for each of other species.

Keywords: assisted reproductive technology, gamete, herbivorous rodent, Microtus montebelli, vole

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, animals and plants have been extinct at a rate far beyond the extinction speed of nature, and the loss of biodiversity caused by such situation is one of the most critical environmental problems in the world.1 The loss of biodiversity leads to the loss of the ecosystem’s capabilities required for the survival of mankind, indicating that it could threaten the human sustainable development and foundation of our life. From this viewpoint, conservation activities of middle‐ and large‐scarce rare wild animal species that are attracting attention are underway.2, 3 On the other hand, although small rodents account for more than half of the mammal species and animals on earth, it is less frequently focused on such smaller mammals and there are few studies aimed at maintaining and restoring the ecological environment, conservation, and regeneration of species. In conservation studies on endangered species, small animal species tend to be less subject to research, while animal species that are beautiful in appearance or useful for human society and daily life become more subject to research.2, 3 Furthermore, small animal species are thought to be more susceptible to environmental changes due to human activities, etc. at an earlier stage. It thus suggests that further research in small animal species including Microtus genus is beneficial to the conservation of biodiversity, accumulation of biological knowledge, and development of academic research field.

The Microtus genus, which is the subject of this article, belongs to the Animalia kingdom, the Chordata phylum, the Vertebrata subphylum, the Mammalia class, the Rodentia order, the Cricetidae family, the Arvicolinae subfamily, and the Microtus genus,4 and most species are widely distributed from the cold to the temperate worldwide. Moreover, many species inhabit the land which has no utility value on agriculture or which has not undergone fluctuation due to human occupation.5 In addition, 77 species inhabit all over the world, and five species(Microtus bavaricus [Critically Endangered], Microtus bedfordi [Vulnerable], Microtus breweri [Vulnerable], Microtus oaxacensis [Endangered], and Microtus umbrosus [Endangered])in this genius are classified beyond an emergency type, “vulnerable”, that requires appropriate and immediate conservation.4 As a characteristic, the Microtus is a herbivorous small rodent with multiple stomachs6, 7 and the number of chromosomes which differs between species.8 Thus, it is expected to be useful as a model for digestion‐metabolism regulation of medium or large herbivorous animals, or species differentiation and species distribution research model.9 Since there are also species that exhibit monogamy that is less than 3% of mammals,10, 11, 12 it is used as a model for social behaviors of human mating systems or brain mechanism research.13, 14, 15 Furthermore, they are also used for research as a tooth regeneration model in regenerative medicine field because of nonforming tooth roots of the molars in this genus.16 Recently, new researches in Microtus such as the establishment of induced pluripotent stem [iPS] cells17 and production of transgenic animals18, 19 in Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole) have been promoted. It is also attracting attention as the prion disease model because of its high susceptibility to transmissible spongiform encephalopathy.20

At present, the reproductive characteristics in Microtus are not fully understood and development of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) that are contributory for the preservation of germ cells and regeneration of individuals is less advanced. However, there are available papers regarding ARTs, for instance, the production of offspring derived from eggs fertilized in vitro with fresh sperm,21, 22 in vitro culture of in vivo fertilized oocytes and embryos,23 establishment of superovulation procedure,24 attempts to sperm cryopreservation in Microtus fortis (Yangtze vole),25 and in vitro culture of in vivo fertilized embryo in prairie vole.26

In consideration of the aforementioned preservation of the species and the supply of laboratory animals, ARTs are important tools. Development of ARTs is progressing rapidly since the analysis of mammalian fertilization mechanism began in the early 20th century.27 ARTs include superovulation, cryopreservation of germ cells, artificial insemination (AI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), micro‐insemination (or intracytoplasmic sperm injection; ICSI), embryo transfer (ET), and so on, and it is possible to produce offspring using ARTs in human, primates without human (baboon, rhesus monkey, and cynomolgus monkey), domestic (cat, horse, cattle, pig, sheep, and goat), and laboratory (rabbit, mouse, rat, and hamster) animals.27 On the other hand, studies on ARTs targeting wild animals have been conducted since around the 1970s and became more active in the 1980s.28, 29 Thus, various ARTs are indispensable technologies to promote the enormous number of wild and rare animal species, and technical modifications should be made specifically for each species in order to improve the validity of ARTs. In this article, we mainly introduce the recent results of applying ARTs to Japanese native species, Microtus montebelli, whose research has been carried out for many years among the Microtus, and also show some results in Microtus arvalis and Microtus rossiaemeridionalis, which have been maintained in our laboratory.

2. ARTS IN M. MONTEBELLI

2.1. Superovulation

A stable supply of large numbers of high‐quality oocytes with high competence for fertilization and embryo development will be important for not only basic reproductive studies but also applied researches in Microtus. Therefore, it is necessary to determine exact methods to collect oocytes as many as possible, especially in the context of the timing of the hormonal treatments in the procedures of superovulation.

Little is known about reproductive activity on vole. It has been reported that M. montebelli exhibits a copulatory ovulation and that its vaginal smear test is not valid to identify specific stages of a regular estrous cycle.30, 31 The pregnancy period is 21 days, and the litter size is largely varied from one to eight (four pups on average).7 Keebaugh et al made a first report on the superovulation of M. ochrogaster, and demonstrated the importance of age of females and the advantage of using young females for the treatments of superovulation.19 Specifically, females aged 6‐11 weeks ovulated more oocytes (14 oocytes on average) compared with females aged 12‐20 weeks (four oocytes on average), although females aged 4‐5 weeks did not produce oocytes. Moreover, in the case that we examined a typical treatment (a combination of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) that were usually used for mouse superovulation) of M. montebelli, we could obtain equivalent results to the mouse cases. Specifically, multiple oocytes could be collected from 3‐week‐old females (before opening vagina).24 These results indicate that there may be differences in the sensitivity to exogenous hormones and/or their acting pathway. We then investigated the more efficient treatment of older females and found that although the follicle development by the eCG administration was absolutely occurred even in mature females, it was difficult to induce the ovulation by the hCG administration. For the purpose of determining the procedures of superovulation in M. montebelli, it was required to find the administration method and reagents which are suitable for this species. Consequently, we found that 20% of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) supplemented gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist (buserelin acetate, PVP‐GnRHa), which was estimated to induce endogenous luteinizing hormone releasing, and the administration of PVP‐GnRHa into cervix subcutaneous could stably and efficiently induce the ovulation in M. montebelli. Moreover, the PVP‐GnRHa caused the higher number of ovulated oocytes than the hCG in 3‐week‐old females. Overall, the establishment of superovulation will promote the research of other ARTs such as IVF, ICSI, and ET in Microtus.

2.2. IVF, ICSI, and ET

The reports regarding IVF are also limited, and the production of zygotes derived from fresh and freeze‐thawing (FT) sperm was reported in M. ochrogaster 26 and M. montebelli (fresh sperm only).21, 22 In these experiments, human tubal fluid (HTF) medium and modified Krebs‐Ringer bicarbonate (mKRB) medium were used for capacitation (0.5 and 2 hours) and insemination. The rates of normal fertilization were 32.6% (fresh) and 29.3% (FT). Moreover, the rate of normal fertilization increased up to approximately 80%, when the insemination medium was supplemented with 1 mM hypotaurine. Then, the production of offspring derived from IVF oocytes was reported in M. montebelli 22 and M. ochrogaster 26 and the transgenic animals were produced in M. ochrogaster 18; the rates of offspring/transferred embryos were 36.7%, 50.0%, and 26.7% (for control), respectively, indicating that the ET was also successful. We also demonstrated that IVF oocytes could be produced with fresh and FT sperm and that resultant embryos were capable of developing to the offspring successfully in M. montebelli. It should be noted that these were enabled by the establishment of the superovulation methods.

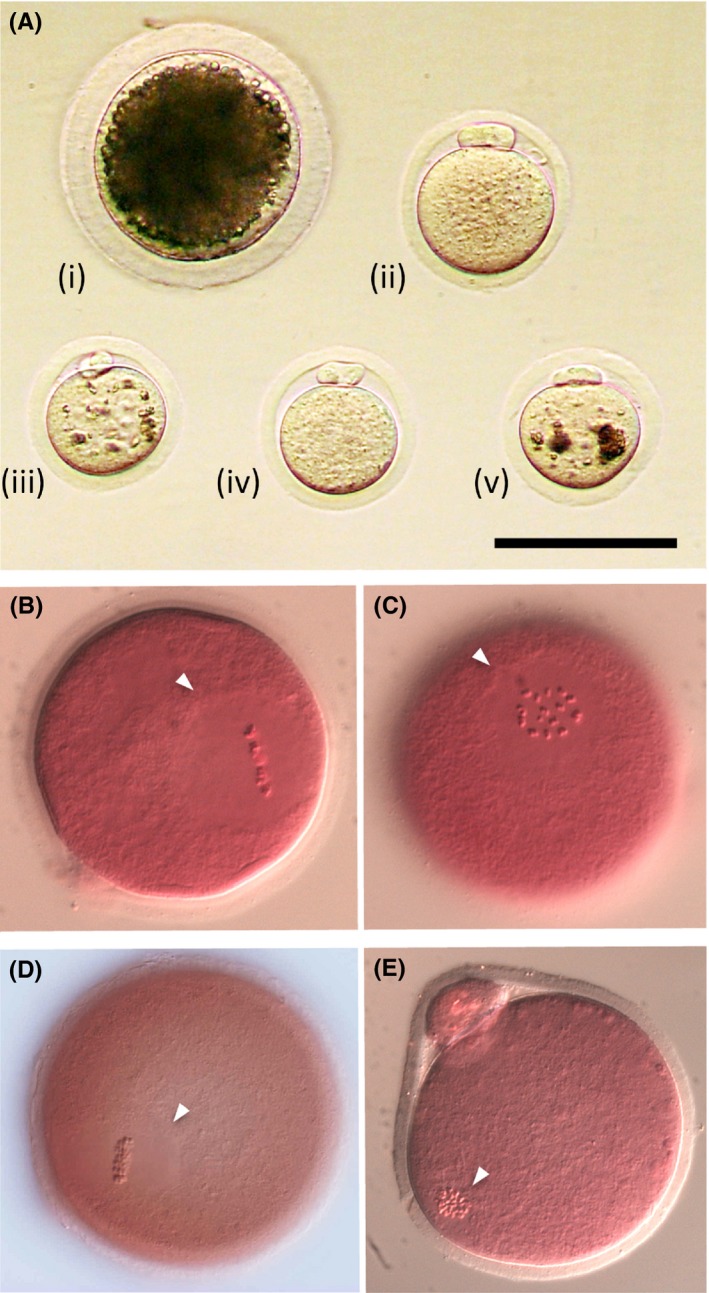

As ICSI is unlikely used for the sperm and oocytes from Microtus genus, we attempted the production of ICSI oocytes and their offspring and are accumulating evidence to demonstrate that the offspring derived from ICSI oocytes could be produced in M. montebelli. Since the diameter of oocyte of M. montebelli (approx. 60 µm, also M. arvalis and M. rossiaemeridionalis) is smaller than that of mice and the oocyte spindle occupies the extensive region in ooplasm (Figure 1), the procedures of ICSI in M. montebelli should be accompanied by discreet manipulation. On the whole, the establishment of stable ICSI technique is beneficial to the other practical technologies such as the somatic nuclear transfer and production of transgenic animals.

Figure 1.

The morphology and nuclear status of Microtus oocytes. A, The matured oocytes from i) Sus scrofa domesticus, ii) Mus musculus (B6D2F1), iii) Microtus arvalis, iv) Microtus montebelli, and v) Microtus rossiaemeridionalis are shown. B‐E, Nuclear status (the metaphase II [MII] stage) of matured oocytes is shown B,C; M. montebelli, D,E; M. musculus). The bar shows 100 µm. The arrowheads indicate the meiotic spindle at MII stage

2.3. Cryopreservation of gamete and embryo

Cryopreservation of oocytes and embryos has not been reported in Microtus genus. In many mammalian species, it is more difficult to survive oocytes and embryos with large cytoplasm than sperm during the cryopreservation. In our experiment on M. montebelli, it has been demonstrated that their oocytes and embryos could be vitrified using the protocol in mice32 and the viability after warming was favorable. Before the technical establishment, we will need the production of offspring derived from vitrified‐warmed oocytes and embryos.

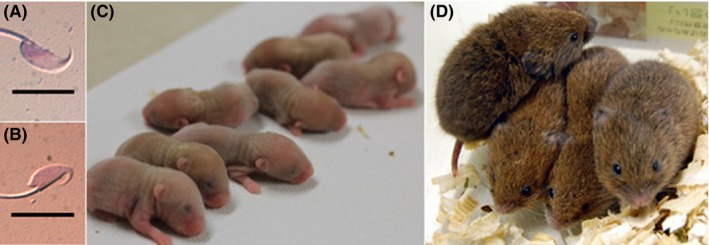

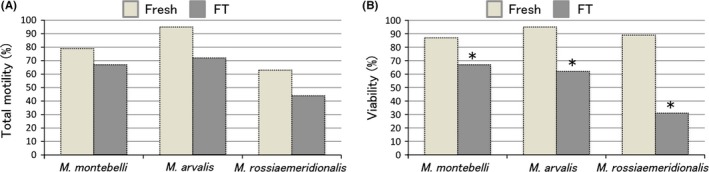

The morphology of M. montebelli sperm is hook‐shaped and unlike mouse and rat sperm whose shapes are sickle. In the head size, there is no noticeable difference among these animals (Figure 2A,B; other two strains are also hook‐shaped).33 Meanwhile, sperm concentrations of the caudal epididymal fluids from M. montebelli are several times as high as those from typical mouse strains (eg, ICR and B6D2F1), M. arvalis and M. rossiaemeridionalis; when sperm were collected from a pair of caudal epididymides in 1 ml of solution (eg cryoprotectant agent, CPA; and culture medium), the maximum sperm concentrations of M. montebelli and other above‐mentioned rodents were approximately 1 × 108 and 2 × 107 cells/ml, respectively (Okada and Kageyama, unpublished data). Thus, M. montebelli might be a suitable animal for the experiments in which many sperm are necessary, because the number of animals used for the experiments can be reduced. The following research is an example of the cryopreservation experiment in which many sperm are necessary. For instance, M. montebelli sperm were cryopreserved in the solution consisted of 18% raffinose and 3% skim milk (R18S3), which is widely used for mouse sperm.34 Motility (visual inspection by microscopy), viability (eosin‐nigrosine staining), DNA damage level (comet assay), and oocyte activation ability (interspecies ICSI test) were evaluated before and after cryopreservation. Although no significant difference was found between fresh (79%) and freeze‐thawed (FT) sperm (67%) in the rates of motile sperm, the rates were likely lower in FT sperm (Figure 3A).33 The rate of live sperm was 87% for fresh sperm, but it was significantly reduced to 67% for FT sperm (Figure 3B).33 The rates of sperm with DNA damages were 2.0% for fresh sperm and 2.5% for FT sperm and did not show any significant differences between these samples. Next, in order to evaluate oocyte activation ability of sperm, single fresh sperm or single FT sperm was injected into an ovulated mouse oocyte. Resultantly, the meiotic resume rates were 100% for both experimental groups. Moreover, all of the injected oocytes that had resumed meiosis further formed female and male pronuclei. In addition, similar results were also obtained in mice (B6D2F1 strain, control group), supporting the results of the evaluated parameters observed in the FT sperm of M. montebelli. These results clearly show that the cryopreservation method for mouse sperm is also valid for at least M. montebelli sperm.

Figure 2.

The morphology of sperm head and offspring derived from nonsurgical artificial insemination (AI) (transcervical insemination) in Microtus montebelli. A,B show the sperm head of B6D2F1 and M. montebelli, respectively. C,B show the offspring derived from fresh and freeze‐thawing (FT) sperm, respectively. The bars in A,B show 10 µm. Photograph in this figure were reused in this paper with the permission of Japanese Journal of Embryo Transfer33

Figure 3.

Total motility A, and viability B, of Microtus sperm before and after freeze‐thaw. The motility was assessed with five categories (+++, ++, +, ±, −) and calculated four categories (+++, ++, +, ±) as the total motility. *Compared with the fresh, there was significance in each species (P < 0.05). These figures were re‐used in this paper with the permission of Japanese Journal of Embryo Transfer33

2.4. AI

AI is one of the ARTs widely used in medium‐ and large‐sized animals, but it is not commonly used in small rodents such as mice and rats. Although the oviduct/intra‐uterine transfer of IVF embryos is a preferable ART rather than AI in small rodents, AI (requiring less artificial manipulation) is a simple and potentially powerful tool for producing offspring.

For AI in small rodents, there are surgical methods such as intrabursal transfer of sperm,35 intra‐oviduct insemination,36 and intra‐uterine insemination.37 Additionally, transcervical insemination38 is available as a nonsurgical method. Surgical AI can be performed with less number of sperm than nonsurgical AI, and it is effective for the animals with the difficulty in the collection of abundant sperm (eg, genetically altered mice), though it requires advanced techniques for surgery.39 On the other hand, the merit of the nonsurgical AI (transcervical insemination) is none of the stress and physical damages that are caused by the surgery,38 and the demerit is the requirement of a relatively large number of sperm (3 × 106 cells/50 µl).40 Furthermore, nonsurgical AI makes it possible to inseminate sperm into and produce offspring repeatedly in the same females. Accordingly, the nonsurgical AI (transcervical insemination) is effective not only for wildlife species and rare species in which the number of available populations is not sufficient, but also for laboratory animals, from the viewpoint of compliance with 3R (replacement, reduction, and refinement). Using transcervical insemination, we are currently attempting to transfer FT sperm of M. montebelli into recipients in order to produce offspring.

Since sperm flagellar movement is considerably interfered with the hypertonicity and viscosity of the CPA (R18S3), the frozen‐thawed sperm suspension is promptly diluted with HEPES‐buffered HTF, cultured for 10 minutes, and centrifuged for the adjustment of sperm concentration. Then, concentration of fresh or FT sperm suspension is adjusted to 2 × 106 cells/20 µl. For the purpose of the induction of superovulation in females for nonsurgical AI, 30 IU of PMSG was administered to them, and 30 IU of hCG was administered 46‐48 hours after the injection of PMSG. Following the injection of hCG, the female was doubling up with the vasectomized male to promote the coitus for infertile‐induced ovulation. Four to six hours after coitus, the female was anesthetized with the mixture of three anesthetics (0.23 mg/kg medetomidine hydrochloride, 3.00 mg/kg midazolam, and 3.75 mg/kg butorphanol),41 and then the aforementioned sperm suspension was directly transferred into each uterine horn by the transcervical method (2 × 106 cells/20 µl/uterine horn). After a treatment, female was treated with atipamezole and awakened.

The number of offspring produced by using transcervical insemination with fresh sperm (7.2 animals on average) tended to be higher than the number of offspring (4.7 animals on average) in natural mating (Table 1, Figure 2C).33 Pregnancy of females was possible by using transcervical insemination with FT sperm at the rate of 37.5%, and the number of born offspring (Figure 2D, 1.7 animals on average)33 was lower than that of natural mating. Interestingly, the litter size was dramatically improved to the equivalent level to that of natural mating by conducting the sperm insemination 7‐9 hours after coitus. These results might be interpreted as showing that the survivability of FT sperm is lower than that of fresh sperm after the insemination into females and that FT sperm inseminated at the timing around the ovulation can successfully fertilize ovulated oocytes in the oviduct. Overall, it is considered that sperm cryopreservation method and AI in M. montebelli were established as the practical methods.

Table 1.

The nonsurgical AI in Microtus montebelli.[Link]

| Treaments | No. of recipients | Pregnancy (%)[Link] | No. of offspring | Ave. no. of offspring (±SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 6 | 6 (100) | 43 | 7.2 ± 1.5 |

| FT | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 5 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| Natural mating | 9 | 7 (77.8) | 33 | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

AI, artificial insemination; FT, freeze‐thawing.

The above‐mentioned data was re‐used in this paper with the permission of Japanese Journal of Embryo Transfer.33

At 14 days post‐AI, it was assessed by the increased weight.

3. ARTS IN M. ARVALIS AND M. ROSSIAEMERIDIONALIS

As mentioned above, the technologies of superovulation, IVF, ICSI and ET, have reached the level of practical application in M. montebelli and they have not been established yet in the other species (M. arvalis and M. rossiaemeridionalis). One of the main causes seems that the treatment with a combination of eCG and GnRH agonist rarely acts for superovulation, suggesting the necessity of examinations of a different superovulation treatment with inhibin antiserum.42 Possible establishment of the techniques for superovulation could make it easier to improve the protocols of IVF, ICSI, and ET as in the case of M. montebelli.

When sperm from M. arvalis and M. rossiaemeridionalis were cryopreserved according to the same procedures as those from M. montebelli, motility and viability decreased after freezing‐thawing (Figure 3)33 and sperm DNA damage rate increased in both species. In addition, the sperm sufficiently retained the ability to activate the oocytes even after freezing‐thawing. These results were similar to those obtained in M. montebelli. On the other hand, when AI with fresh or FT sperm was carried out in M. rossiaemeridionalis, the result is not satisfactory (M. arvalis has not been examined yet). Possible reasons were listed below: (a) the number of sperm that can be collected is small (the testes and caudal epididymides are also small), and sperm collection requires more sensitive handling; (b) it is not easy to prepare a pseudopregnant female by vasectomized males, and (c) although a decrease in motility and viability after freezing‐thawing is commonly observed in all species, the degree of such decrease is relatively large in this species, compared with M. montebelli. Moreover, relatively small size of female reproductive organs (cervix and uterine horn) may also be a negative factor in obtaining nonsurgical AI‐derived offspring. In future, we will solve the above problems and improve the methods to produce offspring these species.

4. CONCLUSION

In this review, it is clearly demonstrated that cryopreservation method of mouse sperm can be applied to the sperm from the three species of Microtus genus and most of ARTs have been successfully established in M. montebelli. These indicate that ARTs developed in laboratory animals are able to be applied to wildlife species and endangered small animal species. Since it is extremely difficult to use wildlife species and endangered species for the development of biotechnologies, accumulation of basic data using laboratory animals is important in order to develop new ARTs which can be applied to wildlife species and endangered species. On the other hand, as observed between different mouse strains, experimental results regarding ARTs were varied among species of the Microtus genus, so it will be necessary to improve ART protocols specifically for each species based on the results obtained with mice and M. montebelli.

As mentioned above, 77 species in this genus are currently confirmed, some of which are already classified as endangered species. It is not easy to avoid extinction at present, it is difficult to continuously grasp in the trend of small animal species, which is hard to attract conservative interest (eg, suddenly classification from stable to endangered state), and thus the applied research must be carried on.

DISCLOSURES

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflict of interest. Human studies: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author. An animal use ethics statement: The designed animal experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Nippon Veterinary and Life Science University. All procedures were complied with guideline for Proper Conduct of Animal Experimental by Science Council of Japan. All animals were humanely treated throughout the course of experiments, and maximum care was taken to minimize pain of experimental animals.

Okada K, Kageyama A. Assisted reproductive technologies in Microtus genus. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;18:121–127. 10.1002/rmb2.12244

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoffmann H, Hilton‐Taylor C, Angulo A et al. The impact of conservation on the status of the world's vertebrates. Science. 2010;330:1503‐1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Small E. The new Noah’s Ark: beautiful and useful species only. Part 1. Biodiversity conservation issues and priorities. Biodiversity. 2012;13:121‐16. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Small E. The new Noah’s Ark: beautiful and useful species only. Part 2. The chosen species. Biodiversity. 2012;13:37‐53. [Google Scholar]

- 4. The International Union for Conservation of Nature; IUCN, RED LIST (2018–1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Kawamura R, Ikeda K. Ecological study of the Microtus montebelli on field causing Tsutsugamushi, Trombicula akamushi (BRUMPT). Doubutsugaku zasshi. 1935;47:90‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kudo H, Oki Y. Breeding and rearing of Japanese field voles (Microtus montebelli Milne‐Edwards) and Hungarian voles (Microtus arvalis Pallas) as new herbivorous laboratory animal species. Jikken Dobutsu. 1982;31:175‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kudo H, Oki Y. Microtus species as new herbivorous laboratory animals: reproduction; bacterial flora and fermentation in the digestive tracts and nutritional physiology . Vet Res Commun. 1984;8:77‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazurok NA, Rubtsova NV, Isaenko AA et al. Comparative chromosome and mitochondrial DNA analyses and phylogenetic relationships within common voles (Microtus Arvicolidae). Chromosome Res. 2001;9:107‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tougard C, Renvoisé E, Petitjean A, Quéré JP. New insight into the colonization processes of common voles: inferences from molecular and fossil evidence. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):121‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter CS, DeVries AC, Getz LL. Physiological substrates of mammalian monogamy: the prairie vole model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:303‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aragona BJ, Wang Z. The prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster): an animal model for behavioral neuroendocrine research on pair bonding. ILAR J. 2004;45:35‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ledford H. ‘Monogamous’ vole in love‐rat shock. Nature. 2008;451:121‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pitkow LJ, Sharer CA, Ren X, Insel TR, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ. Facilitation of affiliation and pair‐bond formation by vasopressin receptor gene transfer into the ventral forebrain of a monogamous vole. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7392‐7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross HE, Freeman SM, Spiegel LL, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ. Variation in oxytocin receptor density in the nucleus accumbens has differential effects on affiliative behaviors in monogamous and polygamous voles. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1312‐1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGraw LA, Young LJ. The prairie vole: an emerging model organism for understanding the social brain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:103‐109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tummers M, Thesleff I. Root or crown: a developmental choice orchestrated by the differential regulation of the epithelial stem cell niche in the tooth of two rodent species. Development. 2003;130:1049‐1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manoli DS, Subramanyam D, Carey C et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from the prairie vole. PLoS One. 2012;7:121‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donaldson ZR, Yang SH, Chan AW, Young LJ. Production of germline transgenic prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) using lentiviral vectors. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:1189‐1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keebaugh AC, Modi ME, Barrett CE, Jin C, Young LJ. Identification of variables contributing to superovulation efficiency for production of transgenic prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carlson CM, Schneider JR, Pedersen JA, Heisey DM, Johnson CJ. Experimental infection of meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) with sheep scrapie. Can J Vet Res. 2015;79:68‐73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wakayama T, Suto J, Matubara Y et al. In vitro fertilization and embryo development of Japanese field voles (Microtus montebelli). J Reprod Fertil. 1995;104:63‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wakayama T, Suto JI, Imamura K, Toyoda Y, Kurohmaru M, Hayashi Y. Effect of hypotaurine on in vitro fertilization and production of term offspring from in vitro‐fertilized ova of the Japanese field vole. Microtus montebelli Biol Reprod. 1996;54:625‐630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wakayama T, Matsubara Y, Imamura K, Kurohmaru M, Hayashi Y, Fukuta K. Development of early‐stage embryos of the Japanese field vole, Microtus montebelli, in vivo and in vitro . J Reprod Fertil. 1994;101:663‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kageyama A, Tanaka M, Morita M, Ushijima H, Tomogane H, Okada K. Establishment of superovulation procedure in Japanese field vole, Microtus montebelli . Theriogenology. 2016;86:899‐905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu LJ, Xu P, Gu JZ, Fu J, Si E, Xie E. Artificial reproduction of the Yangtze field vole: in vitro embryo development and fertilization with fresh and freeze‐thawed sperm. Lab Anim (NY). 2006;35:37‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horie K, Hidema S, Hirayama T, Nishimori K. In vitro culture and in vitro fertilization techniques for prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:907‐911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yanagimachi R. Fertilization studies and assisted fertilization in mammals: their development and future. J Reprod Dev. 2012;58:25‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seager S. The breeding of captive wild species by artificial methods. Zoo Biol. 1983;2:235‐239. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kusuda S. The state of reproductive research and artificial breeding of endangered animals for the purpose of species preservation in domestic zoos. Doubutsuen kenkyu. 2003;7:121‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goto N, Hashizume R, Sai I. Litter size and vaginal smear in (Microtus montebelli). J Mammal Soc Jpn. 1977;7:75‐85. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goto N, Hashizume R, Sai I. Pattern of ovulation in (Microtus montebelli). J Mammal Soc Jpn. 1978;7:181‐189. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakao K, Nakagata N, Katsuki M. Simple and effcient procedure for cryopreservation of mouse embryos by simple vitrification. Exp Anim. 1997;46:231‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okada K, Kageyama A. Sperm cryopreservation and artificial insemination in Microtus genus: as a model for rare and wild small rodents. Jpn J Embryo Transfer. 2017;39:189‐194. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakagata N, Takeshima T. Cryopreservation of mouse spermatozoa from inbred and F1 hybrid strains. Exp Anim. 1993;42:317‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato M, Kimura M. Intrabursal transfer of spermatozoa (ITS): a new route for artificial insemination of mice. Theriogenology. 2001;55:1881‐1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakagata N. Production of normal young following insemination of frozen‐thawed mouse spermatozoa into fallopian tubes of pseudopregnant females. Jikken Dobutsu. 1992;41:519‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakatsukasa E, Inomata T, Ikeda T, Shino M, Kashiwazaki N. Generation of live rat offspring by intrauterine insemination with epididymal spermatozoa cryopreserved at −196 degrees C. Reproduction. 2001;122:463‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stone BJ, Steele KH, Fath‐Goodin A. A rapid and effective nonsurgical artificial insemination protocol using the NSET™ device for sperm transfer in mice without anesthesia. Transgenic Res. 2015;24:775‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sato M, Tanigawa M, Watanabe T. Effect of time of ovulation on fertilization after intrabursal transfer of spermatozoa (ITS): improvement of a new method for artificial insemination in mice. Theriogenology. 2004;62:1417‐1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takeshima T, Toyoda Y. Artificial insemination in the mouse with special reference to the effect of sperm numbers on the conception rate and litter size. Exp Anim. 1977;26:317‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kageyama A, Tohei A, Ushijima H, Okada K. Anesthetic effects of a combination of medetomidine, midazolam, and butorphanol on the production of offspring in Japanese field vole, Microtus montebelli . J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78:1283‐1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takeo T, Nakagata N. Superovulation using the combined administration of inhibin antiserum and equine chorionic gonadotropin increases the number of ovulated oocytes in C57BL/6 female mice. PLos One, 2015;29;10(5):e0128330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]