Abstract

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age and a major cause of infertility; however, the pathophysiology of this syndrome is not fully understood. This can be addressed using appropriate animal models of PCOS. In this review, we describe rodent models of hormone‐induced PCOS that focus on the perturbation of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐ovary (HPO) axis and abnormalities in neuropeptide levels.

Methods

Comparison of rodent models of hormone‐induced PCOS.

Main findings

The main method used to generate rodent models of PCOS was subcutaneous injection or implantation of androgens, estrogens, antiprogestin, or aromatase inhibitor. Androgens were administered to animals pre‐ or postnatally. Alterations in the levels of kisspeptin and related molecules have been reported in these models.

Conclusion

The most appropriate model for the research objective and hypothesis should be established. Dysregulation of the HPO axis followed by elevated serum luteinizing hormone levels, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic disturbance contribute to the complex etiology of PCOS. These phenotypes of the human disease are recapitulated in hormone‐induced PCOS models. Thus, evidence from animal models can help to clarify the pathophysiology of PCOS.

Keywords: androgen, animal models, hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal axis, kisspeptin, polycystic ovary syndrome

1. INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder that affects 5%‐10% of women of reproductive age. PCOS is characterized by infertility, polycystic ovaries, oligo‐/anovulation, hyperandrogenism, and elevated serum luteinizing hormone (LH) levels. This heterogeneous disease also affects reproductive function; patients often exhibit metabolic abnormalities including insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and obesity (Figure 1), which are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and endometrial cancer.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Despite its high prevalence and link to other major health problems, the detailed pathophysiology of PCOS is not fully understood. Since it affects multiple physiological systems, different organs must be analyzed in order to clarify disease etiology. Appropriate animal models can be used to investigate the pathogenesis of PCOS. Administration of steroid hormones and their modulators is the most widely used method to induce PCOS phenotypes in such models and has been applied to ewes, non‐human primates, and rodents at different stages of pre‐ or postnatal development.8, 9, 10 Recent studies have evaluated the role of neuropeptides in the hypothalamus of PCOS model animals including sheep and rodents.11, 12 The latter is easier to handle than larger mammals, which is convenient for analyzing multiple organs especially the brain, since access is limited in human subjects.

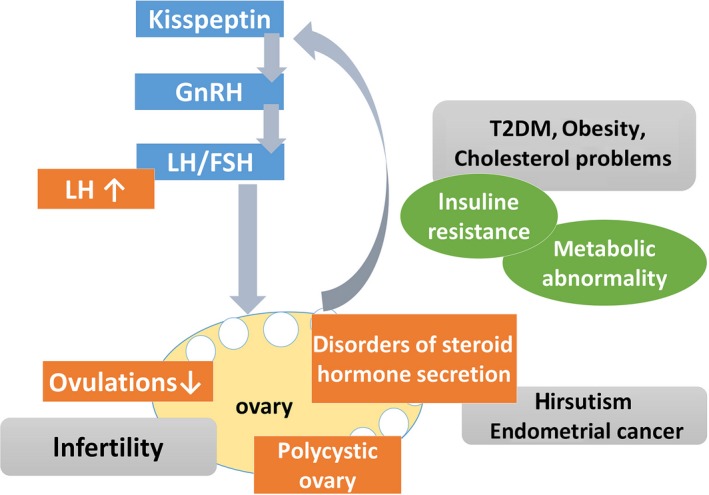

Figure 1.

Major features of human PCOS. PCOS involves dysregulation of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal axis and neuropeptide levels; systemic metabolic disorder and risk of malignant disease are concurrent with reproductive dysfunction

Kisspeptin is a neuropeptide that positively regulates gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion via G protein‐coupled receptor 54 (also known as Kiss1r).13 Given its role in reproductive function, Kisspeptin may be responsible for the higher serum LH level in PCOS patients. In the rodent hypothalamus, Kisspeptin neurons are located in the arcuate (ARC) and anteroventral periventricular (AVPV) nuclei,14, 15 which express sex steroid receptors and engage in negative and positive feedback regulation, respectively. It was also shown that kisspeptin neurons in the ARC coexpress the neuropeptides dynorphin A and neurokinin (NK)B, which inhibit kisspeptin secretion and are therefore referred to as KNDy neurons.16, 17, 18

The purpose of this literature review is to provide an overview of rodent models of hormone‐induced PCOS from the perspective of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal (HPG) axis, including recent evidence for the involvement of neuropeptides such as kisspeptin in this disorder.

2. ANDROGEN‐INDUCED PCOS MODELS

Hyperandrogenism is a major feature of PCOS. It has been suggested that exposure to excessive androgens early in life leads to PCOS in adulthood. As such, several androgens have been used to induce a PCOS‐like condition in rodents including testosterone (T), 5α‐dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA; Table 1).

Table 1.

Hormonal treatments and profiles of rodent PCOS models

| Category | Reagent | Prenatal/Postnatal | Species | Dose and time of treatment | BW | Estrous cyclicity | Ovarian morphology | Sex steroid hormone | Gn | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen | Free T | Prenatal | Rat | 5 mg single dose (GD 20th) | ↑ | Irregular (longer) |

Antral↑, CL↓ |

T↑, E2→, P4→ |

LH↑, LH/FSH↑ |

19 |

| TP | Prenatal | Rat | 3 mg/d, 4 d (GD 16th‐19th) | → | Irregular (longer) |

Preantral↑, Antral↑, Pre‐ov↓, CL↓ |

T → or↑ |

LH→or↑, FSH→ |

20 | |

| Rat |

5 mg/d, 4 d (GD 16th‐19th) |

→ | Irregular (longer) | Polycystic | T↑, E2→, P4→ | N/A | 23 | |||

| Postnatal | Rat | 1.25 mg single dose (PND5 or PND9) | N/A | Acyclic (disetrus) | Polycystic | T↑, E2↓, P4↓ | LH↑ | 21 | ||

| Rat | 1 mg /100 g BW (PND21‐56) | → | Acyclic (disetrus) |

CL‐, Atretic↑ Preantral↑, |

T↑, E2↑, P4→ |

N/A | 22 | |||

| DHEA | Postnatal | Rat | 6 mg /100 g BW from PND21‐23, for 15‐40 d | → | Irregular (mainly estrous) |

Cyctic FC↑, CL↓ |

T↑, E2→ | LH/FSH↑ | 25, 26, 27 | |

| Mouse | 7.5 mg/body, 90‐d (PND21) | → | Regular | Not changed | Not changed | Not changed | 28 | |||

| DHT | Prenatal | Rat |

3 mg/d, 4 d (GD 16th‐19th) |

→ | Irregular |

Antral↓, Pre‐ov↓, Atretic cyst‐like↑ |

T↑or→, E2↑or→, P4↑or→ | LH↑ | 34, 35 | |

| Mouse |

250 µg/d, 3 d (GD16th‐18th) |

→ | Irregular | Atretic cyst‐like↑ |

T↑or→, E2→, P4→or↓ |

LH→ | 12, 24, 33 | |||

| Postnatal | Rat |

7.5 mg/pellet, from 3‐4 wk of age, 90‐d release |

↑ | Acyclic (disetrus) |

Antral↓, Cyctic FC↑, CL↓ |

T → or↓, E2→, P4↓ |

LH→ | 30, 34, 35 | ||

| Mouse |

2.5‐10 mg/body, 90‐d release (from PND21) |

↑ | Acyclic (disetrus) | Atretic cyst‐like↑ |

T→, E2→, P4↓ |

LH→ | 28, 33 | |||

| Aromatase inhibitor | Letrozole | Postnatal | Rat | 1‐3 mg/kg/day, adult, 21‐23 consecutive days | ↑ | Acyclic (disetrus) | Cystic FC ↑ |

T↑, E2↓, P4↓ |

LH↑, FSH↑ |

43, 44 |

| Rat | 9‐36 mg/body, 90‐d release (from PND21) | ↑ | Acyclic (disetrus) | Cystic FC ↑ |

T↑, E2→, P4↓ |

LH↑, FSH→ |

42 | |||

| Mouse |

8 mg/body, 90‐day release pellet (from PND21) |

→ | Acyclic (disetrus) or irregular |

Unhealthy large antral↑, Hemorrhagic cyst+ |

T↑, E2→, P4→ |

LH→, FSH→ |

28 | |||

| Antiprotestin | RU486 | Postnatal (adult) | Rat | 2‐4 mg/100 g BW adult for 1‐2 wk | N/A | Acyclic (estrous) | Atretic FC ↑ |

T↑, E2↑, T/E2↑ |

LH↑ (PA↑) |

52, 54, 55 |

| Estrogen | EV | Postnatal (adult) | Rat | 2 mg/body, single dose, adult | → | Acyclic (estrous) |

Primodial↑, Primaly↓, Antral↓, CL↓, Cyctic FC↑ |

T↑, E2↑ |

LH↓, FSH↓ |

56 |

| Rat | 4 mg/body, single dose, adult | ↓ | N/A |

Atretic FC↑ CL↓ |

T↓, P4↑ E2→ |

LH↑, FSH→ |

58, 61 |

↑, increased; →, no change; ↓, decreased; BW, body weight; DHT, 5α‐dihydrotestosterone; EV, estradiol valerate; FC, follicle; GD, gestational day; Gn, gonadotropin; N/A, not available; PA, pulse amplitude; PND, postnatal; pre‐ov, preovulatory; TP, testosterone propionate.

2.1. T‐induced PCOS models

Pre‐ or postnatal administration of T can induce hyperandrogenemia in rats. In addition, prenatal exposure to T during the critical period of fetal development was shown to cause developmental and morphological abnormalities in the reproductive system.19, 20 For prenatal administration, pregnant rats were given a single‐dose injection of 5 mg free T on gestational day 20 or of T propionate (TP) from day 16 to 19 (3 mg T daily) of pregnancy.19, 20 Postnatally, rats were administered TP at 1.25 mg/100 g body weight at 5 days of age21 or were injected daily with TP at 1 mg/100 g body weight from 21 to 56 days of age.22

2.1.1. Estrous cyclicity

Rats treated prenatally with T exhibited longer and irregular estrous cycles.19, 23 Rats treated postnatally showed a disruption of estrous cyclicity and persistent diestrus.21, 22

2.1.2. Ovarian morphology

The numbers of preantral and antral follicles were increased whereas those of preovulatory follicles and corpus luteum (CL) cells were decreased in the ovaries of rats treated prenatally with T as compared to control rats. Cystic follicles were also observed in prenatal T‐treated rats.19, 24 On the other hand, rats that were postnatally administered T showed large cystic or atretic follicles and luteinization of theca cells in the ovaries.19

2.1.3. Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

In prenatal T‐treated rats, T and LH levels and the LH/follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio in the estrus phase were higher than in control animals. However, FSH, estradiol (E2), and progesterone (P4) levels did not differ significantly from those in controls after single‐dose treatment.19, 22, 24 In rats treated postnatally with T, serum T, LH, and prolactin (PRL) levels were increased whereas P4 and E2 levels were decreased relative to control animals that received a single‐dose treatment.21

2.1.4. Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

In ewes that were prenatally administered T, there were fewer KNDy cells within the ARC expressing both neurokinin‐3 receptor and kisspeptin; however, the number of cells positive for kisspeptin only was higher relative to control ewes.11

2.1.5. Metabolic features and adiposity

Prenatal T treatment caused an increase in blood glucose levels in rats without affecting body weight.23 On the contrary, the body weight of postnatal T‐treated rats increased when the animals were fed a high‐fat diet while fasting glucose levels were unaffected.22

2.1.6. Summary

Postnatal T treatment caused morphological changes in the ovary of rats that reflected the human PCOS phenotype. On the other hand, prenatal T treatment in rats increased the number of preantral and antral follicles although cystic follicles and ovary weight were unaffected in this model and the observed changes did not correspond to the ovarian morphology of human PCOS. Serum T levels were increased by both pre‐ and postnatal T treatment. Serum E2 and P4 levels were unaltered by prenatal T administration while continuous postnatal T treatment increased E2 levels, possibly due to the conversion of T. An increased number of kisspeptin‐positive cells in the ARC of prenatal T‐treated ewes may be associated with defects in the feedback control of GnRH/LH secretion 11; however, a limitation of this study is that they did not examine LH levels and ovarian morphology.

2.2. DHEA‐induced PCOS models

DHEA is an androgen that is primarily produced in the adrenal gland. Women with PCOS have high levels of DHEA; therefore, DHEA is administered to rodents to generate PCOS models. A typical protocol is 6 mg/100 g body weight/day starting from postnatal day 21 to 23 for about 20‐40 consecutive days.25, 26, 27 DHEA has been administered by implantation of 7.5‐mg 90‐day continuous‐release pellets in mouse models.28

2.2.1. Estrous cyclicity

DHEA‐treated rats showed irregular cycles, mainly remaining in estrus.29, 30 In contrast, DHEA‐treated mice showed regular cycles.28

2.2.2. Ovarian morphology

Ovary weight in postnatal DHEA‐treated rats was increased relative to that in controls27, 31; this was accompanied by ovarian cyst expansion, an increased number of cystic follicles, granular cell layer thinning, and thickening of the theca cell layer.29, 31 DHEA‐treated mice showed normal ovary weight and growing follicle and CL populations.28

2.2.3. Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

In the serum of DHEA‐treated rats, LH levels were lower but T levels and LH/FSH ratio were higher than in control rats.29, 32 Serum levels of FSH, LH, E2, T, and P4 did not differ significantly between DHEA‐treated and control mice.28

2.2.4. Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

An analysis of GnRH, Kiss1, and Kiss1r mRNA levels in the hypothalamus of postnatal DHEA‐treated rats revealed a reduction in Kiss1 transcript levels relative to the control.32

2.2.5. Metabolic features and adiposity

In DHEA‐treated rats, fasting serum glucose levels were increased whereas body and fat weights were unchanged as compared to the control.31, 32, 33 Brown adipose tissue activity in rats was reduced by postnatal DHEA administration 33; however, serum total cholesterol, insulin sensitivity, fat depot weight, and adipocyte cell size were unaltered. DHEA‐treated mice also had a lower body weight than controls.28

2.2.6. Summary

Postnatal DHEA treatment in rats caused irregular cycles and increased LH/FSH ratio while decreasing LH level relative to controls, reflecting PCOS‐like ovaries. However, DHEA‐treated mice did not exhibit these features. Kiss1 mRNA level was decreased in the hypothalamus of DHEA‐treated rats, which was accompanied by higher T and lower LH levels in the serum. Postnatal DHEA‐treated rats are useful for investigating the impact of higher T in the ovary, but may not be the optimal model for high LH levels in disorders characterized by negative feedback regulation.

2.3. DHT‐induced PCOS models

DHT is not converted into E2 by aromatase; therefore, the PCOS phenotype can be analyzed in DHT‐treated animals without considering the effects of estrogen converted from androgens.

2.3.1. Prenatal DHT‐treated models

To generate prenatal DHT‐treated animals, mice were injected with 250 µg of DHT on days 16, 17, and 18 of gestation 28 whereas rats were administered 3 mg of DHT daily from gestational day 16 to 19. The offspring served as prenatal DHT‐treated PCOS models.34, 35

Estrous cyclicity

Rats and mice prenatally administered DHT showed irregular cycles. The mice spent more days in diestrus and fewer in proestrus than controls,28, 34 resulting in a decrease in the number of litters produced per 3 months.36

Ovarian morphology

Rats prenatally treated with DHT had fewer normal large, antral, preovulatory follicles and CLs, and more atretic cyst‐like follicles. Ovaries of prenatal DHT‐treated rats had a similar mass to those of control animals.34 In prenatal DHT‐treated mice, CL and antral follicle wall areas were decreased but the number of atretic cyst‐like follicles and thickness of the antral follicle theca cell layer were increased compared to control mice.28, 36

Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

Prenatal DHT‐treated diestrus rats had higher levels of LH and E2 and lower levels of P434, 35; however, in mice the P4 levels were decreased whereas E2, T, and gonadotropin levels were unchanged relative to the control.28

Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

There was a significant increase in the number of kisspeptin‐ and NKB‐positive cells in the ARC of the hypothalamus in prenatal DHT‐treated rats, whereas the number of kisspeptin‐positive cells in the AVPV did not differ from that in control animals in diestrus.34 It was recently reported that γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) input to GnRH‐expressing neurons was increased in mice that were prenatally administered DHT.37

Metabolic features and adiposity

The body weights of prenatal DHT‐treated rats and mice were similar to those of control animals.34, 36 However, adipocyte area in parametrial fat and the degree of steatosis were increased relative to the control group by prenatal treatment with DHT.28

Summary

Prenatal DHT‐treated rats and mice had irregular estrous cycles and PCO‐like ovarian morphology. Increased LH levels were observed in prenatal DHT‐treated rodents with a corresponding upregulation of kisspeptin in the ARC. On the other hand, there was no observable change in body weight. This is similar to the PCOS phenotype, which is characterized by normal body weight and enhanced LH secretion.

2.3.2. Postnatal DHT‐treated models

For postnatal DHT treatment, rats were subcutaneously administered DHT pellets (7.5 mg/pellet, 90‐day release, daily dose = 83 µg) on postnatal day 21,34, 38, 39 whereas in mice a tube containing 10 mg DHT was implanted subcutaneously at this time point.28.

Estrous cyclicity

The estrous cycle of postnatal DHT‐treated rats and mice was completely disrupted, with most animals remaining in diestrus.28, 34

Ovarian morphology

Ovary volume was decreased in postnatal DHT‐treated as compared to control rats.34, 38 Additionally, ovaries in the model group had large, atretic antral follicles and fewer CL than those of control animals. Postnatal DHT‐treated mice had more atretic cyst‐like follicles and fewer CL. Ovary weight did not differ between postnatal DHT‐treated and control mice.28, 38

Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

In postnatal DHT‐treated rats and mice, LH, FSH, E2, and T levels did not differ significantly from those in controls, although P4 was downregulated.28, 34, 38

Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

Kiss1 mRNA expression was reduced in the ARC of the hypothalamus in postnatal DHT‐treated rats.40 Meanwhile, the number of kisspeptin‐positive cells showed a decreasing tendency and there were fewer NKB‐positive cells in the ARC of postnatal DHT‐treated as compared to control rats.34

Metabolic features and adiposity

Rats treated postnatally with DHT showed increased body weight and fat deposition, larger adipocytes, and decreased insulin sensitivity and muscle (tibialis anterior) weight compared to controls; these were associated with upregulation of insulin‐like growth factor‐1 expression.41 In mice, postnatal DHT treatment increased body weight, serum total cholesterol level, amount of fat deposit, and adipocyte cell size28 while reducing adiponectin levels and insulin sensitivity33 relative to control animals.

Summary

Postnatal DHT‐treated rats and mice showed similarities in phenotype. However, some of these differed from the features observed in humans. In particular, LH levels were unchanged in both models and ovary volume was decreased in the rat model. The decreased kiss1 mRNA expression and number of kisspeptin‐positive cells in the ARC of this rat model may result from a negative feedback effect of higher androgen levels. On the other hand, metabolic status—including insulin resistance and adiposity—was similar to that of human PCOS. Thus, this model is appropriate for investigating the metabolic features of PCOS.

3. AROMATASE INHIBITOR‐INDUCED MODELS

3.1. Letrozole

Aromatase is an enzyme that converts T and androstenedione into E2 and estrone, respectively. Letrozole, a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, blocks the conversion of androgens to estrogen and thus increases androgen level. As such, letrozole has been used to generate animal models of PCOS mostly by postnatal administration; in some cases, it was continuously administered to immature or adult rats (3‐8 weeks of age) from about day 21 to 90.28, 38, 42, 43 In rat models, letrozole doses vary from 1‐3 mg daily by oral administration to 100‐400 µg/d/100 g body weight by implantation of a subcutaneous pellet (Table 1).44, 45, 46 For mouse models, 9 mg letrozole were delivered via 90‐day continuous‐release pellets starting from postnatal day 21.28

3.1.1. Estrous cyclicity

Letrozole‐treated rats and mice were completely acyclic.28, 38 Vaginal smears from this rat model revealed an abundance of leukocytes, the predominant cell type of the diestrus phase.38

3.1.2. Ovarian morphology

Letrozole‐treated rats showed increases in ovary weight, area of the largest follicle, and number of cystic follicles as compared to control rats, and their ovaries contained atretic antral follicles and follicular cysts.38, 42, 46 The ovaries of letrozole‐treated mice showed an increased number of unhealthy large antral follicles and hemorrhagic cysts relative to control animals.28

3.1.3. Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

Serum LH, FSH, and T levels in letrozole‐treated rats were elevated relative to those in control animals in estrous and diestrus. Moreover, serum E2 and progesterone levels were lower in these rats than in proestrus and diestrus controls, respectively.42, 43 In mice treated with letrozole, serum T levels were higher whereas LH, FSH, E2, and P4 levels were similar to those in control animals.

3.1.4. Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

Kiss1 mRNA expression levels in the posterior hypothalamus were higher in letrozole‐treated as compared to control rats, whereas no difference was observed in the anterior hypothalamus.42 Additionally, in letrozole‐treated rats, the levels of neurotransmitters that inhibit GnRH and LH release (serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and acetylcholine) were reduced whereas that of a stimulatory neurotransmitter (glutamate) was increased in the hypothalamus and pituitary.47

3.1.5. Metabolic features and adiposity

Continuous administration of letrozole (200 µg/d) to 21‐day‐old female rats for 90 days yielded animals with the metabolic features of human PCOS such as increased body weight, inguinal fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and enlarged adipocytes in inguinal and mesenteric fat depots.46 On the other hand, body and fat deposit weights and adipocyte size were unaltered by the treatment.28

3.1.6. Summary

Letrozole‐induced PCOS model rats exhibit acyclicity, cystic ovarian morphology corresponding to human PCOS, elevated serum LH levels, and higher Kiss1 mRNA expression in the posterior hypothalamus than control rats. This model recapitulates the metabolic features of human PCOS, including a PCO‐like morphology and elevated serum LH levels, and is therefore appropriate for investigating human PCOS. The elevated Kiss1 mRNA and serum LH levels indicate that enhanced KNDy neuron activity was associated with impairment of the negative feedback effect of sex steroid hormones.

4. PROGESTERONE RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST‐INDUCED MODELS

4.1. RU486

RU486 (mifepristone), a progesterone receptor antagonist, is one the most common drugs used for emergency contraception. The binding affinity of RU486 to progesterone receptor is five times greater than that of P4.48 Thus, RU486 can potently block the functions of progesterone.49 Evidence from clinical studies indicates that RU486 suppresses follicle development, ovulation, and CL formation50, 51 by disrupting the negative feedback of P4 to the hypothalamus. Accordingly, RU486 has been used to generate rat models of PCOS by administering 2 mg RU486/100 g body weight to adult rats for 1‐2 weeks.52, 53, 54

4.1.1. Estrous cyclicity

After 4 days of RU486 treatment, rats showed irregular cycles consisting of persistent estrous.46, 47, 48

4.1.2. Ovarian morphology

The ovaries of RU486‐treated rats showed follicular growth arrest and a higher rate of follicular atresia.52, 54, 55 The numbers of preantral and small antral follicles and atretic cyst‐like follicles—but not of large antral follicles—were also increased relative to untreated rats.52

4.1.3. Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

Serum concentrations of estradiol, T, LH, and PRL were elevated in RU486‐treated as compared to control rats; this was accompanied by a higher mean amplitude of LH pulses.52, 53, 55

4.1.4. Neuropeptides in the hypothalamus

Kisspeptin immunoreactivity was increased in the ARC of RU486‐treated as compared to control rats.52

4.1.5. Metabolic features and adiposity

Serum insulin levels tended to increase following RU486 administration, but the difference relative to untreated rats was not statistically significant.53

4.1.6. Summary

Rats with RU486‐induced PCOS harbored atretic cyst‐like follicles in the ovaries similar to human PCOS and had irregular estrous cycles with increased serum LH concentration and pulse amplitude. Moreover, kisspeptin expression was upregulated in the ARC of the hypothalamus in these animals relative to the control, reflecting a lack of negative feedback from progesterone. This model is appropriate for investigating the impairment of the negative feedback effect of progesterone in PCOS pathophysiology, although the persistent estrous and high estradiol levels do not correspond to human PCOS.

5. ESTROGEN‐INDUCED MODELS

5.1. EV (E2 valerate)

EV is a long‐acting estrogen. Rat models of EV‐induced PCOS have been established by injecting young adult female rats in estrus with a single dose of 2‐4 mg EV.56, 57, 58

5.1.1. Estrous cyclicity

At 2 days after EV treatment, rats were mostly in estrus or proestrus‐estrus; by 20 days, all of the animals were in constant estrus.56

5.1.2. Ovarian morphology

The ovaries of EV‐treated rats harbored large cyst‐like follicles. Five to 16 days after EV injection, many of the follicles showed severe atresia; ovary weight declined 16 days after EV injection, resulting in ovaries of reduced size compared to control animals.56

5.1.3. Gonadotropin and sex steroid profiles

Basal serum levels of LH declined following EV injection before gradually recovering; the levels were lower than control values 8 weeks of postinjection. Serum FSH levels showed a similar profile. However, plasma LH concentration was increased in EV‐treated rats relative to the proestrus control after GnRH injection.59 Administration of 2 mg EV also increased T and E2 levels,60 whereas a concentration of 4 mg reduced T and increased LH and P4 but had no effect on E2 levels.61

5.1.4. Metabolic features and adiposity

The body weight of EV‐treated rats was comparable to that of control animals.60 However, the weight of inguinal fat depots was higher in the former than in the latter group. There was no difference in insulin sensitivity between treated and untreated rats.61

5.1.5. Summary

EV‐induced PCOS model rats exhibit a cystic ovarian morphology; however, ovary weight was decreased by administration of a single dose of 2 mg/body. These models showed persistent estrous 20 days after EV injection. The levels of sex steroid hormones and gonadotropins differ according to the administered dose of EV.

6. CONCLUSION

In this review, we described hormone‐induced rodent models of PCOS. Evidence for the roles of neuropeptides in the hypothalamus of PCOS models has been updated and is described above (Table 2).62 Researchers should choose models whose features are suited to their research objectives; we described models that recapitulate different aspects of the PCOS phenotype in each summary, and it is hoped that this review will aid researchers in the selection of the appropriate animal model. PCOS animal models can be classified as first, second, or third generation. Models induced with estrogen and T are considered as first‐generation models, since these are established by simply mimicking the hormonal profiles of PCOS patients. However, there are some problems with these models that are overcome in second‐generation animal models generated by treatment with letrozole and DHT. For example, one problem with T‐treated models is that T is converted whereas DHT is not aromatized to estradiol, while letrozole can increase endogenous T. Transgenic mice treated with DHT represent the third generation of PCOS models and can be used to investigate the mechanistic basis for the PCOS phenotype induced by hormonal treatment. Findings from studies using these animal models can provide important and novel insights into the pathophysiology of PCOS in humans.

Table 2.

Alteration of hypothalamic neuropeptides after hormonal treatment

| Treatment | Prenatal/Postnatal | Species | Neuropeptides in hypothalamus | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Prenatal | Ewe | Dual‐labeled NK3R/Kiss cells ↓, Single‐labeled Kisspeptin‐positive cells ↑ (ARC) | 11 |

| Postnatal | Rat (OVX) | Kiss1↓, GnRHa→, Kiss1r→, NKB↓, pDyn↓ (mRNA of whole hypothalamus) | 62 | |

| DHEA | Postnatal | Rat | Kiss1↓, GnRHa→, Kiss1r→ (mRNA of whole hypothalamus) | 32 |

| DHT | Prenatal | Rat | Kisspeptin‐ and NKB‐positive cells ↑ (ARC) | 34 |

| Mouse | Increased GABA input to GnRH neurons (POA) | 37 | ||

| Postnatal | Rat | Kiss1 mRNA ↓ (ARC) | 40 | |

| Rat | Kisspeptin‐ and NKB‐positive cells ↓ (ARC) | 34 | ||

| Letrozole | Postnatal | Rat | Kiss1 mRNA ↑ (posterior hypothalamus) | 42 |

| RU486 | Postnatal | Rat | Kisspeptin immunoreactivity ↑ (ARC) | 52 |

| Estradiol | Postnatal | Rat (OVX) | Kiss1↓, GnRHa→, Kiss1r→, NKB↓, pDyn→ (mRNA of whole hypothalamus) | 62 |

↑, increased; →, no change; ↓, decreased; ARC, arcuate nucleus; OVX, ovariectomized; POA, preoptic area.

DISCLOSURES

Conflict of interest: Satoko Osuka, Natsuki Nakanishi, Tomohiko Murase, Tomoko Nakamura, Maki Goto, Akira Iwase, and Fumitaka Kikkawa declare that they have no conflict of interest. Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any study with human or animal participants performed by any of the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (no. 17K16844 to S.O.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Osuka S, Nakanishi N, Murase T, et al. Animal models of polycystic ovary syndrome: A review of hormone‐induced rodent models focused on hypothalamus‐pituitary‐ovary axis and neuropeptides. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;18:151–160. 10.1002/rmb2.12262

REFERENCES

- 1. Kubota T. Update in polycystic ovary syndrome: New criteria of diagnosis and treatment in Japan. Reprod Med Biol. 2013;12:71‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:219‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cussons AJ, Watts GF, Burke V, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Stuckey B. Cardiometabolic risk in polycystic ovary syndrome: a comparison of different approaches to defining the metabolic syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2352‐2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis 1. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(6):774‐800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(13):853‐861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):347‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsilchorozidou T, Overton C, Conway GS. The pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 2004;60(1):151‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noroozzadeh M, Behboudi‐Gandevani S, Zadeh‐Vakili A, Ramezani TF. Hormone‐induced rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review. Life Sci. 2017;191:259‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shi D, Vine DF. Animal models of polycystic ovary syndrome: A focused review of rodent models in relationship to clinical phenotypes and cardiometabolic risk. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:185‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abbott DH, Nicol LE, Levine JE, Xu N, Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA. Nonhuman primate models of polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;373:21‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahn T, Fergani C, Coolen LM, Padmanabhan V, Lehman MN. Prenatal testosterone excess decreases neurokinin 3 receptor immunoreactivity within the arcuate nucleus KNDy cell population. J Neuroendocrinol. 2015;27:100‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moore AM, Prescott M, Marshall CJ, Yip SH, Campbell RE. Enhancement of a robust arcuate GABAergic input to gonadotropin‐releasing hormone neurons in a model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:596‐601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1614‐1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adachi S, Yamada S, Takatsu Y, et al. Involvement of anteroventral periventricular metastin/kisspeptin neurons in estrogen positive feedback action on luteinizing hormone release in female rats. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:367‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3686‐3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, et al. Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin‐releasing hormone secretion in the goat. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3124‐3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li D, Mitchell D, Luo J, et al. Estrogen regulates KiSS1 gene expression through estrogen receptor α and SP protein complexes. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4821‐4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: Kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: A central node in the control of gonadotropin‐releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3479‐3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tehrani FR, Noroozzadeh M, Zahediasl S, Piryaei A, Azizi F. Introducing a rat model of prenatal androgen‐induced polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:792‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tehrani FR, Noroozzadeh M, Zahediasl S, Piryaei A, Hashemi S, Azizi F. The time of prenatal androgen exposure affects development of polycystic ovary syndrome‐like phenotype in adulthood in female rats. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:151‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ota H, Fukushima M, Maki M. Endocrinological process rat treated with and histological ovary aspects propionate of the in the of polycystic formation testosterone. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1983;1983:121‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu C, Lin F, Qiu S, Jiang Z. The characterization of obese polycystic ovary syndrome rat model suitable for exercise intervention. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:151‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah AB, Nivar I, Speelman DL. Elevated androstenedione in young adult but not early adolescent prenatally androgenized female rats. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:151‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qu F, Liang Y, Zhou J, et al. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation alleviates the hyperandrogenism of polycystic ovarian syndrome rats by regulating the expression of P450arom and CTGF in the ovaries. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:7754‐7761. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abramovich D, Irusta G, Bas D, Cataldi NI, Parborell F, Tesone M. Angiopoietins/TIE2 system and VEGF are involved in ovarian function in a DHEA rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3446‐3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang F, Yu B, Yang W, Liu J, Lu J, Xia X. Polycystic ovary syndrome resembling histopathological alterations in ovaries from prenatal androgenized female rats. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5:151‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu W, Liu W, Fu Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Bak Foong pills combined with metformin in the treatment of a polycystic ovarian syndrome rat model. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:1819‐1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caldwell A, Middleton LJ, Jimenez M, et al. Characterization of reproductive, metabolic, and endocrine features of polycystic ovary syndrome in female hyperandrogenic mouse models. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3146‐3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang D, Wang W, Liang Q, et al. DHEA‐induced ovarian hyperfibrosis is mediated by TGF‐β signaling pathway. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:151‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ward RC, Costoff A, Mahesh VB. The induction of polycystic ovaries in mature cycling rats by the administration of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHA). Biol Reprod. 1978;18:614‐623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jang M, Lee MJ, Lee JM, et al. Oriental medicine Kyung‐Ok‐Ko prevents and alleviates dehydroepiandrosterone‐induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in rats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwasa T, Matsuzaki T, Tungalagsuvd A, et al. Effects of chronic DHEA treatment on central and peripheral reproductive parameters, the onset of vaginal opening and the estrous cycle in female rats. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:752‐755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yuan X, Hu T, Zhao H, et al. Brown adipose tissue transplantation ameliorates polycystic ovary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2708‐2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Osuka S, Iwase A, Nakahara T, et al. Kisspeptin in the hypothalamus of two rat models of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 2017;158:367‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu X‐Y, Li Z‐L, Wu C‐Y, et al. Endocrine traits of polycystic ovary syndrome in prenatally androgenized female Sprague‐Dawley rats. Endocr J. 2010;57:201‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore AM, Prescott M, Campbell RE. Estradiol negative and positive feedback in a prenatal androgen‐induced mouse model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrinology. 2013;154:796‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Silva MS, Prescott M, Campbell RE. Ontogeny and reversal of brain circuit abnormalities in a preclinical model of PCOS. JCI Insight. 2018;3(7):pii:99405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mannerås L, Cajander S, Holmäng A, et al. A new rat model exhibiting both ovarian and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3781‐3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Keller J, Mandala M, Casson P, Osol G. Endothelial dysfunction in a rat model of PCOS: Evidence of increased vasoconstrictor prostanoid activity. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4927‐4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brown RE, Wilkinson DA, Imran SA, Caraty A, Wilkinson M. Hypothalamic kiss1 mRNA and kisspeptin immunoreactivity are reduced in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Brain Res. 2012;1467:151‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ergenoglu M, Yildirim N, Yildirim A, et al. Effects of resveratrol on ovarian morphology, plasma anti‐mullerian hormone, IGF‐1 levels, and oxidative stress parameters in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:942‐947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matsuzaki T, Tungalagsuvd A, Iwasa T, et al. Kisspeptin mRNA expression is increased in the posterior hypothalamus in the rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr J. 2017;64:7‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baravalle C, Salvetti NR, Mira GA, Pezzone N, Ortega HH. Microscopic characterization of follicular structures in letrozole‐induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in the rat. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:830‐839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li D, Li C, Xu Y, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in the ovaries from letrozole‐induced rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35:177‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee BH, Indran IR, Tan HM, et al. A dietary medium‐chain fatty acid, decanoic acid, inhibits recruitment of Nur77 to the HSD3B2 promoter in vitro and reverses endocrine and metabolic abnormalities in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 2016;157:382‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maliqueo M, Sun M, Johansson J, et al. Continuous administration of a P450 aromatase inhibitor induces polycystic ovary syndrome with a metabolic and endocrine phenotype in female rats at adult age. Endocrinology. 2013;154:434‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chaudhari N, Dawalbhakta M, Nampoothiri L. GnRH dysregulation in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a manifestation of an altered neurotransmitter profile. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:151‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wessel L, Balakrishnan‐Renuka A, Henkel C, et al. Long‐term incubation with mifepristone (MLTI) increases the spine density in developing Purkinje cells: New insights into progesterone receptor mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:1723‐1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zheng Q, Li Y, Zhang D, et al. ANP promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells by NPRA/PGRMC1/EGFR complex and improves ovary functions of PCOS rats. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weisberg E, Croxatto HB, Findlay JK, Burger HG, Fraser IS. A randomized study of the effect of mifepristone alone or in conjunction with ethinyl estradiol on ovarian function in women using the etonogestrel‐releasing subdermal implant, Implanon®. Contraception. 2011;84:600‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Niinimäki M, Ruokonen A, Tapanainen JS, Järvelä IY. Effect of mifepristone on the corpus luteum in early pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:448‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kondo M, Osuka S, Iwase A, et al. Increase of kisspeptin‐positive cells in the hypothalamus of a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:673‐681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lakhani K, Yang W, Dooley A, et al. Aortic function is compromised in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:651‐656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ruiz A, Aguilar R, Tébar AM, Gaytán F, Sánchez‐Criado JE. RU486‐treated rats show endocrine and morphological responses to therapies analogous to responses of women with polycystic ovary syndrome treated with similar therapies. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:1284‐1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sanchez‐Criado JE, Sanchez A, Ruiz A, Gaytan F. Endocrine and morphological features of cystic ovarian condition in antiprogesterone RU486‐treated rats. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993;129:237‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brawer JR, Munoz M, Farookhi R. Development of the polycystic ovarian condition (PCO) in the estradiol valerate‐treated rat. Biol Reprod. 1986;35:647‐655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Linares R, Hernández D, Morán C, et al. Unilateral or bilateral vagotomy induces ovulation in both ovaries of rats with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mesbah F, Moslem M, Vojdani Z, Mirkhani H. Does metformin improve in vitro maturation and ultrastructure of oocytes retrieved from estradiol valerate polycystic ovary syndrome‐induced rats. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8:151‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schulster A, Farookhi R, Brawer JR. Polycystic ovarian condition in estradiol valerate‐treated rats: spontaneous changes in characteristic endocrine features. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:587‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Karimzadeh L, Nabiuni M, Sheikholeslami A, Irian S. Bee venom treatment reduced C‐reactive protein and improved follicle quality in a rat model of estradiol valerate‐induced polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2012;18:384‐392. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stener‐Victorin E, Ploj K, Larsson BM, Holmäng A. Rats with steroid‐induced polycystic ovaries develop hypertension and increased sympathetic nervous system activity. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Iwasa T, Matsuzaki T, Yano K, Yanagihara R, Mayila Y, Irahara M. The effects of chronic testosterone administration on hypothalamic gonadotropin‐releasing hormone regulatory factors (Kiss1, NKB, pDyn and RFRP) and their receptors in female rats. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(5):437‐441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]