Abstract

The amniote clade Parareptilia is notable in that members of the clade exhibited a wide array of morphologies, were successful in a variety of ecological niches and survived the end-Permian mass extinction. In order to better understand how mass extinction events can affect clades that survive them, we investigate both the species richness and morphological diversity (disparity) of parareptiles over the course of their history. Furthermore, we examine our observations in the context of other metazoan clades, in order to identify post-extinction survivorship patterns that are present in the clade. The results of our study indicate that there was an early increase in parareptilian disparity, which then fluctuated over the course of the Permian, before it eventually declined sharply towards the end of the Permian and into the Triassic, corresponding with the end-Permian mass extinction event. Interestingly, this is a different trend to what is observed regarding parareptile richness, that shows an almost continuous increase until its overall peak at the end of the Late Permian. Moreover, richness did not experience the same sharp drop at the end of the Permian, reaching a plateau until the Anisian, before dropping sharply and remaining low, with the clade going extinct at the end of the Triassic. This observed pattern is likely to be due to the fact that, despite the extinction of several morphologically distinct parareptile clades, the procolophonoids, one of the largest parareptilian clades, were diversifying across the Permian–Triassic boundary. With the clade's low levels of disparity and eventually declining species richness, this pattern most resembles a ‘dead clade walking’ pattern.

Keywords: Parareptilia, Reptilia, Sauropsida, diversity, Permian, Triassic

1. Introduction

Parareptilia was one of the major clades of amniotes that was prevalent during the Permian and Triassic, representing an important component of continental ecosystems during this time frame and occupying numerous ecological niches. Parareptiles are particularly interesting in that they survived the end-Permian mass extinction event, but not the subsequent end-Triassic mass extinction event. There are several potential types of evolutionary scenarios illustrating how the survivors react in the aftermath of a mass extinction. Four prevalent post-mass-extinction patterns that were identified by Jablonski [1] are as follows: (i) decline and recovery, (ii) post-extinction adaptive radiation, (iii) unbroken continuity, and (iv) dead clade walking. These patterns, although frequently cited in studies of invertebrates, have rarely been examined in the context of terrestrial vertebrates, and parareptiles represent an ideal candidate for this.

Parareptiles are considered to be characterized by a better fossil record than many of their contemporaries, reflected in part by a consistently high mean completeness of fossil parareptile taxa in contrast with other coeval tetrapod clades [2]. The earliest known member is Erpetonyx arsenaultorum from the Late Carboniferous of Laurasia [3]. Currently, this taxon represents the only parareptile of Carboniferous age, limiting our knowledge of the group during this period. During the early Permian numerous parareptile lineages appeared and the clade became a notable component of various localities [4,5], and by the late Permian, the clade achieved considerable species richness and a cosmopolitan distribution [6]. However, the end-Permian mass extinction caused the disappearance of most parareptilian lineages, with only one clade, Procolophonoidea, surviving into the Mesozoic [7]. Despite the extinction of all other parareptilian clades, procolophonoids were very successful during the Triassic and were an important component of the post-extinction recovery fauna [8,9].

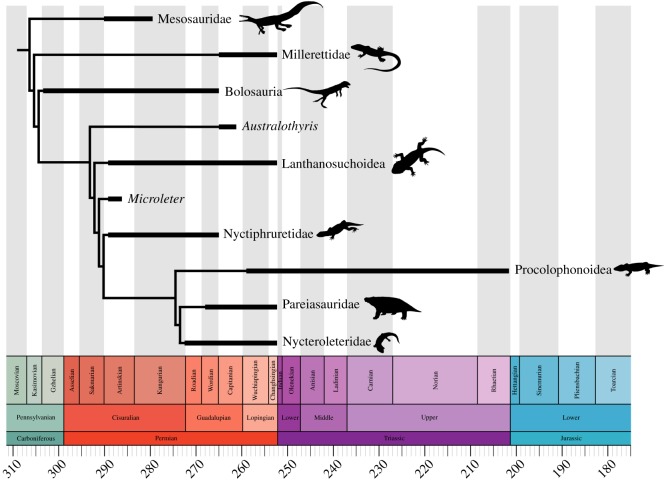

Parareptiles exhibit a wide array of morphologies and were successful in numerous different ecological niches. Known morphologies within the clade vary dramatically, ranging from smaller, superficially lizard-like forms, to large, armoured herbivores. The earliest parareptiles from the late Carboniferous and early Permian included small, carnivorous forms, such as the bolosaurian Erpetonyx, lanthanosuchoids and nyctiphruretids [3,5,10–13], as well as the secondarily aquatic mesosaurs, which exhibit numerous adaptations for life away from terrestrial environments [4,14–16]. The middle Permian saw the appearance of semi-aquatic lanthanosuchoids with anamniote-like features [17], the small, predatory millerettids [18], the enigmatic nycteroleters, which exhibited a true tympanic middle ear [19,20], and the large, herbivorous and often armoured pareiasaurs [21,22]. Lastly, the procolophonoids, many of which are characterized by distinctive skull ornamentation and specializations for herbivory [7,23,24], first appear in the late Permian [7,25]. Overall, it is quite clear that the evolutionary history of Parareptilia is characterized by considerable experimentation and the appearance of numerous distinct morphologies (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simplified version of the stratigraphically calibrated parareptile supertree (modified from the phylogenies of: Ruta et al. [26], Tsuji & Müller [27] and MacDougall et al. [28]) featuring the major clades that were present through the course of parareptilian evolution. Thickened black bars represent the observed ranges of taxa. (Online version in colour.)

Previously, there has been little attention given to quantifying parareptile species richness and especially disparity, despite the importance of the clade as a major component of Permian continental ecosystems. Disparity can allow us to infer details regarding how clades change over time, as well as how they are affected by extinction events. The most prominent study of parareptile richness was undertaken by Ruta et al. [26], focusing on taxic and phylogenetic richness estimates as well as origination and extinction rates of the clade. Currently, there has only been one study quantifying parareptile disparity [29], and in this case, only a single parareptile clade (Procolophonoidea) was investigated. However, despite being acknowledged as a morphologically diverse clade, there has yet to be any attempt to quantify the morphological disparity of Parareptilia as a whole. Furthermore, there have been few studies of terrestrial vertebrates that have examined and applied Jablonski's post-mass-extinction scenarios [1]. This study aims to rectify these gaps in our knowledge by investigating and quantifying the diverse array of parareptile morphologies that were present using modern statistical analyses of disparity, allowing us to compare parareptile phylogenetically estimated species richness with their morphological diversity (disparity) during the Palaeozoic and into the Mesozoic. We also compare the disparity patterns identified in parareptiles with those of other metazoan clades that have passed through mass extinction events.

2. Material and methods

(a). Time bins

For all of our analyses, we used stratigraphic stages as our time bins. These were not combined or split up into smaller bins. The use of time bins of the same length is generally not considered practical with regard to parareptiles, due to the patchiness of their fossil record and the uncertainty surrounding the ages of many formations [26]. Parareptile taxa were placed in time bins based upon age data available in the literature. We attempted to be as accurate as possible, and in most cases the ages of taxa were based on the age range of the formation or stage they were found in (see electronic supplementary material, table S1), but more precise absolute age data were also used when available [30,31].

(b). Analysis of parareptile species richness

A phylogenetic richness estimate (incorporating ghost lineages) was used in lieu of a taxic richness estimate (raw counts of species observed) to examine overall parareptilian species richness. Although a Lagerstätten effect was not apparent in the analysis of parareptilian fossil completeness [2], taxonomic richness can be influenced by sampling biases resulting from highly productive regions [26]. In the case of parareptiles, this potentially includes areas such as the Karoo Basin in South Africa, and the Richards Spur locality in Oklahoma, USA. The species richness of parareptiles was calculated using an approach similar to that of Ruta et al. [26]. For their analysis of parareptilian richness, they used a supertree based on Tsuji & Müller [27], which they then modified by grafting on several parareptile taxa, that were not included in the previous analysis, based on the results of other parareptile studies.

We further modified the supertree of Ruta et al. [26] with the addition of several more parareptile taxa (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), which were grafted onto the tree based on their positions in recent phylogenetic analyses of Parareptilia. Furthermore, the positions of some of the previously included taxa were also modified based on recent analyses [3,5,13,28,32–34]. The taxa that were added were as follows: E. arsenaultorum [3], Delorhynchus priscus and Delorhynchus cifellii [32,35], Abyssomedon williamsi [13], Feeserpeton oklahomensis [12], Phonodus dutoitorum [36], Ruhuhuaria reiszi [37], Mandaphon nadra [34], Obirkovia gladiator [38], Contritosaurus simus [39] and Honania complicidentata [33]. Sanchuansaurus pygmaeus is removed and replaced with Shansisaurus xuecunensis, as the former is now considered a junior synonym of the latter [40]. Tokosaurus perforatus was also removed, as it is considered to be a junior synonym of Macroleter poezicus [20]. Lastly, due to the recent studies that suggest that Eunotosaurus africanus falls within Eureptilia [41,42], it was removed from the tree.

This analysis was conducted in the statistical software R using the packages paleotree [43] and geoscale [44].

(c). Analysis of parareptile disparity

The data matrix of MacDougall et al. [28] was used in order to examine parareptilian disparity through the Palaeozoic and into the Mesozoic, as it is one of the most up-to-date matrices of the clade currently available and, furthermore, it includes representatives of all major parareptilian clades. The matrix was modified by the addition of several procolophonoid parareptiles so that the Triassic disparity of the clade could be better quantified. The added taxa were as follows: R. reiszi, Sclerosaurus armatus, Hypsognathus fenneri, Leptopleuron lacertinum and Anomoiodon liliensterni. The updated data matrix and character list can be found in electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.

The first part of our disparity analysis involved the reconstruction of ancestral taxa. Ancestral character states were estimated at each node in the phylogeny using the likelihood-based rerooting function of the R package Claddis. This is a procedure that was first suggested by Brusatte et al. [45]. The ancestral character values were then bound with the original data matrix. Next, we produced a morphological distance matrix for use in the analysis, calculating distances between all pairwise combination of tips and reconstructed ancestors. The distance measure used to calculate the morphological distances between taxa was the maximum observable rescaled distance, as this method has been shown to be more suitable for datasets with large amounts of missing data [46]. The distance matrix was subsequently subjected to a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). The disparity in each time bin was then calculated as the sum of variances and the sum of ranges of the PCo coefficients of each taxon found in that time bin.

To account for different sample sizes between the different time bins, the dataset was subjected to taxonomic bootstrapping: five taxa were sampled with replacement in each time bin in which there was more than a single taxon.

To quantify the shape of the disparity curves through time, we calculated their centre of gravity (CG). Hughes et al. [47] presented a method of rescaling the CG of a time series, so that the values lay between 0 and 1. A CG value of 0 indicates a ‘bottom heavy’ disparity curve (disparity concentrated early in the history of the clade), a value of 1 indicates a ‘top heavy’ disparity curve (peak disparity not reached until late in the clade's history) and a value of 0.5 indicates a symmetrical curve. The CG of all 1000 bootstrap disparity curves, produced using both sum of variances and sum of ranges, was calculated in R using the equations presented in Hughes et al. [47]. For each curve, CG value was calculated for the Permian only and the complete time series.

This analysis was conducted in the statistical software R using the packages Claddis [46], phytools [48] and geoscale [44].

3. Results

(a). Species richness through time

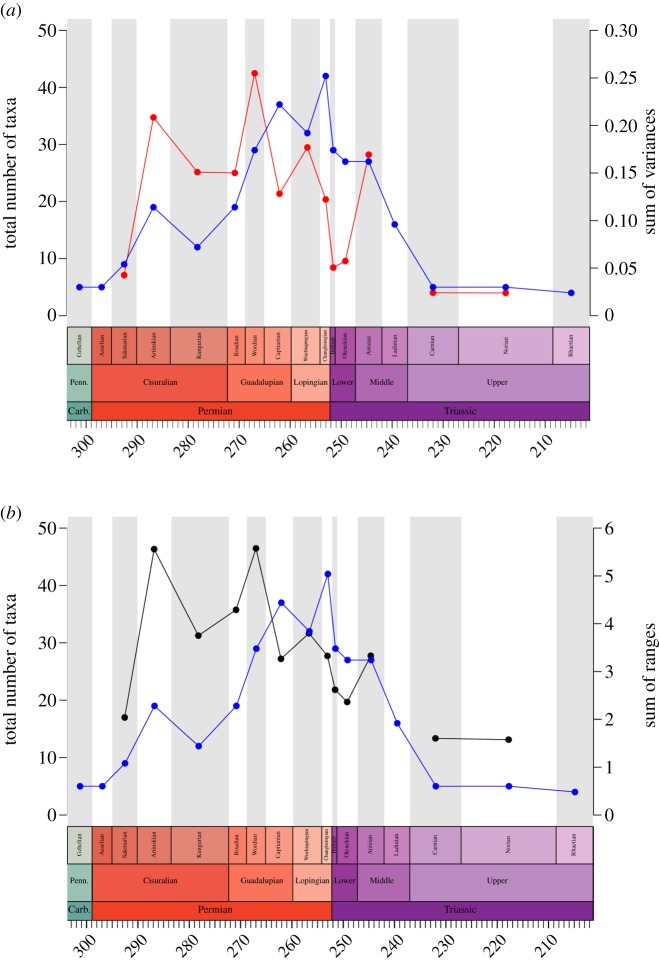

The result of the phylogenetic richness estimate (figure 2) shows that overall parareptilian species richness increased steadily during the late Palaeozoic. After the clade appeared in the Late Carboniferous, parareptile species richness increased rapidly during the Artinskian with the appearances of the major clades Lanthanosuchoidea, Nyctiphruretidae and Bolosauridae. Thereafter, parareptilian richness generally continued to increase, with a second peak occurring in the Capitanian, corresponding with the appearance of the clade Pareiasauridae and a third in the Changhsingian, that corresponds with the appearance of the parareptile clades Nycteroleteridae and Procolophonoidea. There is a decline in parareptilian richness of about 25% across the Permian–Triassic boundary and into the Induan, but this decrease plateaus during the Middle Triassic. However, after this plateau, parareptile richness steadily declines, reaching very low levels. This low richness is maintained for the remainder of the Triassic, until the extinction of the clade during the Rhaetian.

Figure 2.

Plot illustrating changes in parareptile species richness and disparity through time. (a) Richness curve (blue) plotted with the disparity curve produced by the sum of variances (red), and (b) richness curve (blue) plotted with the disparity curve produced by the sum of ranges (black). Stratigraphic stages are used as time intervals. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Morphological disparity through time

The patterns observed in the analyses of disparity are similar when using either the sum of variances or the sum of ranges to calculate disparity; however, there are some slight differences between the two. Overall, the pattern that is observed for both analyses (figure 2) is that there was an early peak in parareptilian disparity during the early Permian (Artinskian). Parareptilian disparity fluctuates for the remainder of the Permian with a series of troughs and peaks. After the Wuchiapingian parareptilian disparity declined sharply towards the end of the Permian and into the Triassic, with Induan disparity being very low. During the Anisian, there is a brief spike in disparity, before the disparity of the clade fell to its lowest levels during the Late Triassic.

The centres of gravity calculated for both disparity curves (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) are very similar, which is expected, given the similar shape of the two curves. The centres of gravity indicate that the overall pattern of disparity observed in parareptiles is bottom heavy, meaning that the disparity of the clade is concentrated earlier in their evolutionary history. When looking at just the Permian, the centres of gravity indicate that the pattern of disparity was slightly top heavy.

4. Discussion

(a). Parareptile disparity patterns in the context of other metazoan clades

Parareptiles are just one of many metazoan clades that have passed through a mass extinction event, thus it is worth comparing the patterns we find in our study with the evolutionary patterns that have been identified in other groups. In recent years, there have been several studies investigating the disparity of various metazoan clades and the effects that mass extinctions have had on these groups. Interestingly, while there are some similarities, many of these groups have disparity patterns that are distinct from what we observe in parareptiles.

While it is difficult to summarize and neatly fit all of the disparity patterns that have been observed in the fossil record into distinct categories, there are some patterns that are particularly prevalent. These various patterns are as follows:

-

(1)

Decline and recovery (continuity with setbacks of Jablonski [1]): the disparity of a clade is dramatically reduced by a mass extinction event; however, after the event, the clade rebounds and a rapid increase in disparity is observed, often reaching or surpassing pre-mass extinction event levels. This particular pattern has been observed in graptoloids across the end-Ordovician mass extinction event [49], in crinoid echinoderms [50–52] and ammonoids [53,54] across the end-Permian mass extinction event, as well as in therian mammals, on the basis of molar shape, across the end-Cretaceous extinction event [55].

-

(2)

Post-extinction adaptive radiation (unbridled diversification of Jablonski [1]): the disparity of a clade is low prior to a mass extinction event, and then immediately after the extinction event disparity rapidly increases. This pattern has been identified in blastoid echinoderms across the end-Ordovician mass extinction event [56], archosauromorphs across the end-Permian mass extinction event [57] and acanthomorph teleosts across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction [58]. This pattern is usually attributed to the clade radiating to fill new areas of ecospace left empty by the mass extinction.

-

(3)

Unbroken continuity [1]: the disparity of a clade is not dramatically affected by a mass extinction event, with disparity levels being only slightly reduced (and rather continuously throughout the clade's history) or not at all (sometimes even rising across the event). This pattern has been observed in anomodont [59] and cynodont [60] synapsids across the end-Permian mass extinction event, as well as shark tooth disparity across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event [61].

-

(4)

Dead clade walking [1]: overall, as has been observed in other metazoan clades, there are several distinct patterns regarding how disparity is affected by mass extinction events. Interestingly, the pattern we see in parareptiles is different in some ways from what is observed in these other clades, though not unique [1,62].

Our results indicate that parareptile disparity was dramatically affected by the end-Permian mass extinction event, in a similar manner to graptoloids [49], crinoids [52] and therian mammals [55] in other events. However, following the end-Permian mass extinction, parareptile disparity remained very low for most of the Triassic. This is distinct from the patterns observed in clades that passed through an extinction event and had dramatic reductions in disparity, but later showed recoveries. Furthermore, unlike graptoloids [49], crinoids [52], archosauromorphs [57], therian mammals [55] and acanthomorphs [58], it is apparent that parareptiles were not entering a phase of rapidly and continuously increasing disparity after the extinction event. Instead, parareptile disparity experienced a brief rebound followed by a second period of decline that eventually lead to the clade's extinction at the end of the Triassic, a stark contrast to many of the aforementioned clades.

Strictly in the context of disparity, this pattern resembles the ‘dead clade walking’ pattern of Jablonski [1,62]. While there is a very brief rebound in disparity early in the Triassic, Triassic disparity levels are overall very low and are never maintained at a high level. This lack of a maintained increase in disparity and the eventual extinction of parareptiles could potentially have been due to competition with the archosauromorphs that were rapidly diversifying taxonomically and morphologically in the same time frame [57].

Furthermore, as indicated by the obtained low centres of gravity (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), parareptiles exhibit a bottom heavy pattern of disparity, with their highest levels of disparity being concentrated earlier in their evolutionary history. This is a similar pattern to what is observed in other, coeval clades such as anomodonts [59], and is in general a trend for metazoan clades [47,63]. However, it is in contrast with the contemporaneous reptile clade, Captorhinidae, which has been shown to be top heavy with regard to disparity, reflecting the adaptive radiation of the herbivorous members of the clade [64].

(b). Parareptile species richness during the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic

Species richness patterns of parareptiles have been investigated and discussed to some degree in past studies; however, much of this research has been based on the known fossil record, with few attempts to correct for sampling biases. The first large-scale study of the richness of Parareptilia using phylogeny in correcting the estimates was undertaken by Ruta et al. [26]. Their study recovered an overall peak in the Wuchiapingian (raw richness) and Wordian (phylogenetically corrected richness), respectively, and an additional Triassic peak in the Olenekian as well as a minor high in the Norian. The results of their study further indicate that parareptilian richness during the Permian is not considerably higher than during the Triassic, suggesting that the clade was not as heavily affected by the end-Permian mass extinction as some other tetrapod groups. More recently, Verrière et al. [2] investigated the quality of the fossil record of parareptiles by assessing the completeness of parareptile taxa and compared their results with an up-to-date but raw (phylogenetically uncorrected) generic richness of the clade. The richness curve is generally very similar to the taxic richness curve of Ruta et al. [26]; however, it has the additional observation of a richness low in the Kungurian.

The differences between our results and those of Ruta et al. [26] are most likely to be the result of the enormous increase in our knowledge of Parareptilia over the last several years. There have been numerous new parareptile taxa described since their study was published, and the interrelationships of some of the major parareptilian clades have been updated in recent phylogenetic analyses [3,28]. Furthermore, there have been updates to the ages of the stratigraphic stages during the Palaeozoic [65], which altered the stage some taxa appear in.

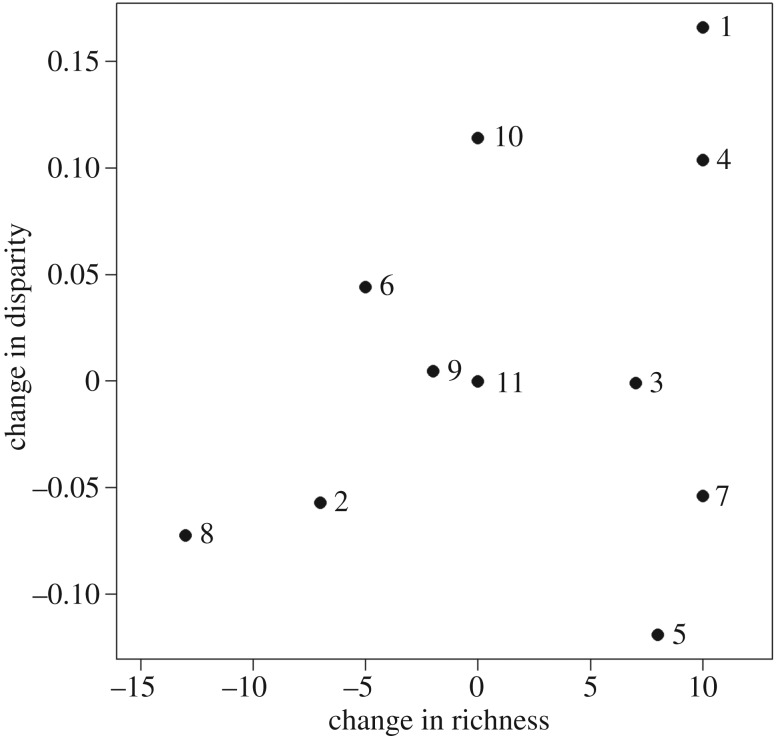

(c). Contrasts between parareptilian species richness and disparity

The results of our study show that while there are similarities between parareptile species richness and disparity patterns, there are also clear differences. The overall pattern observed is that large declines in richness always correspond with large drops in disparity; however, increases in richness do not necessarily always accompany increases in disparity (figure 3). One of the most notable changes in richness and disparity is during the transition from the Permian to the Triassic. While parareptile richness did suffer a large decline as a result of the end-Permian mass extinction event, this decline was arrested for the rest of the Early Triassic, with the richness of the clade stabilizing at around 3/4 of its former level, and does not continue to decline until later in the Middle Triassic. By contrast, parareptilian disparity declined sharply during the late Permian and into the Triassic with no interruptions, resulting in Induan levels of disparity being very low. This post-Permian difference between the two metrics was clearly the result of the diversification of procolophonoids during this period of time. Despite the extinction of several morphologically distinct parareptile clades at the end of the Permian, the Procolophonoidea, one of the most speciose parareptilian clades [29], was diversifying in terms of species richness at the same time [66]. However, the clade was rather morphologically conservative, being restricted to small, superficially lizard-like insectivores and herbivores, which potentially accounts for the low levels of disparity that are observed.

Figure 3.

Plot illustrating the relationship between changes in species richness and changes in disparity over the course of parareptilian evolution. Each point represents the change observed between two stratigraphic stages; the point labels are as follows: 1, Sakmarian–Artinskian; 2, Artinskian–Kungurian; 3, Kungurian–Roadian; 4, Roadian–Wordian; 5, Wordian–Capitanian; 6, Capitanian–Wuchiapingian; 7, Wuchiapingian–Changhsingian; 8, Changhsingian–Induan; 9, Induan–Olenekian; 10, Olenekian–Anisian; 11, Carnian–Norian. Some changes between stages could not be investigated due to disparity not being known for stages that contain only a single taxon.

As discussed by Jablonski [1], there are numerous extrinsic and intrinsic factors that can determine how a clade is affected by mass extinction events. In the case of parareptiles, when looking at the differences between their disparity and species richness patterns, it is clear that multiple divergent factors are coming into play. While disparity levels are heavily affected by the end-Permian mass extinction event, richness is not, and in fact there is actually a substantial diversification of procolophonoid parareptiles during the Early and Middle Triassic [66]. When considering both disparity and richness of Parareptilia, it is clear that procolophonoids are diversifying through the end-Permian mass extinction event and become very speciose early in the Triassic [66], yet they are quite restricted in the niches that they occupy and do not enter any others. Furthermore, Jablonski notes that species richness is not necessarily the best indicator of how a clade is affected by an extinction event [1]. Thus, when both richness and disparity are examined, it is reasonable to ascribe the ‘dead clade walking’ pattern to Parareptilia.

5. Conclusion

Morphological disparity is an aspect of vertebrate evolution that in recent years has been frequently investigated for various groups by palaeontologists. However, in the case of parareptiles, disparity is an aspect of the clade's evolution that has been largely ignored, despite its importance in understanding the evolutionary history of a clade. Thus, we examined both the phylogenetic estimated species richness and the morphological disparity of Parareptilia. Our results indicate that the richness of parareptiles increased throughout the Late Palaeozoic and reached its highest point at the end of the Permian. There was a decline in richness immediately after the end-Permian mass extinction event, but it plateaued at roughly 3/4 of its former amount. However, it sharply declined during the Middle Triassic, with the clade going extinct by the end of the Triassic. Likewise, our results show that the morphological disparity of the clade also reached its highest peak during the Permian, but it sharply declined to very low levels through the late Permian and the end-Permian mass extinction event. The differences between the two metrics are the result of the disappearance of most major parareptile clades during the mass extinction event, and the diversification of procolophonoid parareptiles in the same time frame. Thus, despite a decline in overall disparity and niche occupation, richness of the clade was at first not dramatically affected, though the clade eventually goes extinct by the end of the Triassic. Overall, the ‘dead clade walking’ pattern best characterizes the pattern observed in parareptiles.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Wagner and another anonymous reviewer for their very helpful and constructive comments regarding the manuscript.

Data accessibility

All data used in the study are included in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

M.J.M. drafted the manuscript and collected all included data; M.J.M. and N.B. conducted the statistical analyses used in the study; N.B. and J.F. edited the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

M.J.M. is funded by a DAAD-Leibniz Postdoctoral Scholarship and a Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellowship, N.B. is funded by a DFG research fellowship from the German Research Foundation (DFG BR 5724/1-1), and J.F. is funded by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG FR 2457/5-1 and DFG FR 2457/6-1).

References

- 1.Jablonski D. 2001. Lessons from the past: evolutionary impacts of mass extinctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5393–5398. ( 10.1073/pnas.101092598) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verrière A, Brocklehurst N, Fröbisch J. 2016. Assessing the completeness of the fossil record: comparison of different methods applied to parareptilian tetrapods (Vertebrata: Sauropsida). Paleobiology 42, 680–695. ( 10.1017/pab.2016.26) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modesto SP, Scott DM, MacDougall MJ, Sues H-D, Evans DC, Reisz RR. 2015. The oldest parareptile and the early diversification of reptiles. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20141912 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.1912) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modesto SP. 2010. The postcranial skeleton of the aquatic parareptile Mesosaurus tenuidens from the Gondwanan Permian. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 30, 1378–1395. ( 10.1080/02724634.2010.501443) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDougall MJ, Modesto SP, Reisz RR. 2016. A new reptile from the Richards Spur locality, Oklahoma, USA, and patterns of Early Permian parareptile diversification. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 36, e1179641 ( 10.1080/02724634.2016.1179641) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.deBraga M, Reisz RR. 1996. The Early Permian reptile Acleistorhinus pteroticus and its phylogenetic position. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 16, 384–395. ( 10.1080/02724634.1996.10011328) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cisneros JC. 2008. Phylogenetic relationships of procolophonid parareptiles with remarks on their geological record. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 6, 345–366. ( 10.1017/S1477201907002350) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modesto SP, Damiani RJ, Neveling J, Yates AM. 2003. A new Triassic owenettid parareptile and the mother of mass extinctions. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 23, 715–719. ( 10.1671/1962) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith RMH, Botha-Brink J. 2005. The recovery of terrestrial vertebrate diversity in the South African Karoo Basin after the end-Permian extinction. C.R. Palevol 4, 623–636. ( 10.1016/j.crpv.2005.07.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly E. 1969. A new procolophonoid reptile from the Lower Permian of Oklahoma. J. Paleontol. 43, 676–687. ( 10.2307/1302462) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modesto SP. 1999. Colobomycter pholeter from the Lower Permian of Oklahoma: a parareptile, not a protorothyridid. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 19, 466–472. ( 10.1080/02724634.1999.10011159) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDougall MJ, Reisz R. 2012. A new parareptile (Parareptilia, Lanthanosuchoidea) from the Early Permian of Oklahoma. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 32, 1018–1026. ( 10.1080/02724634.2012.679757) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDougall MJ, Reisz RR. 2014. The first record of a nyctiphruretid parareptile from the Early Permian of North America, with a discussion of parareptilian temporal fenestration. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 172, 616–630. ( 10.1111/zoj.12180) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gervais P. 1865. Du Mesosaurus tenuidens, reptile fossile de l'Afrique australe. Rendus Académie Sci. 60, 950–955. [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Huene F. 1941. Osteologie und systematische Stellung von Mesosaurus. Palaeontogr. Abt. A 92, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modesto SP. 2006. The cranial skeleton of the Early Permian aquatic reptile Mesosaurus tenuidens: implications for relationships and palaeobiology. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 146, 345–368. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00205.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivakhnenko MF. 1980. Lanthanosuchids from the Permian of the East European Platform. Paleontol. Inst. USSR Acad. Sci. 2, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gow CE. 1972. The osteology and relationships of the Millerettidae (Reptilia: Cotylosauria). J. Zool. 167, 219–264. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1972.tb01731.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller J, Tsuji LA. 2007. Impedance-matching hearing in Paleozoic reptiles: evidence of advanced sensory perception at an early stage of amniote evolution. PLoS ONE 2, e889 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000889) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji LA, Müller J, Reisz RR. 2012. Anatomy of Emeroleter levis and the phylogeny of the nycteroleter parareptiles. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 32, 45–67. ( 10.1080/02724634.2012.626004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MSY. 1997. A taxonomic revision of pareiasaurian reptiles: implication for Permian terrestrial palaeoecology. Mod. Geol. 21, 231–298. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuji LA, Sidor CA, Steyer J-S, Smith RMH, Tabor NJ, Ide O. 2013. The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger—VII. Cranial anatomy and relationships of Bunostegos akokanensis (Pareiasauria). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 33, 747–763. ( 10.1080/02724634.2013.739537) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisz RR, Sues H-D. 2000. Herbivory in late Paleozoic and Triassic terrestrial vertebrates. In Evolution of herbivory in terrestrial vertebrates (ed. H-D Sues), pp. 9–41 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reisz RR. 2006. Origin of dental occlusion in tetrapods: signal for terrestrial vertebrate evolution? J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 306B, 261–277. ( 10.1002/jez.b.21115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Säilä LK. 2009. Alpha taxonomy of the Russian Permian procolophonoid reptiles. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 54, 599–608. ( 10.4202/app.2009.0017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruta M, Cisneros JC, Liebrecht T, Tsuji LA, Müller J. 2011. Amniotes through major biological crises: faunal turnover among parareptiles and the end-Permian mass extinction. Palaeontology 54, 1117–1137. ( 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01051.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuji LA, Müller J. 2009. Assembling the history of the Parareptilia: phylogeny, diversification, and a new definition of the clade. Foss. Rec. 12, 71–81. ( 10.1002/mmng.200800011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDougall MJ, Scott D, Modesto SP, Williams SA, Reisz RR. 2017. New material of the reptile Colobomycter pholeter (Parareptilia: Lanthanosuchoidea) and the diversity of reptiles during the Early Permian (Cisuralian). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 180, 661–671. ( 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlw012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cisneros JC, Ruta M. 2010. Morphological diversity and biogeography of procolophonids (Amniota: Parareptilia). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 8, 607–625. ( 10.1080/14772019.2010.491986) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodhead J, Reisz R, Fox D, Drysdale R, Hellstrom J, Maas R, Cheng H, Edwards RL. 2010. Speleothem climate records from deep time? Exploring the potential with an example from the Permian. Geology 38, 455–458. ( 10.1130/G30354.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDougall MJ, Tabor NJ, Woodhead J, Daoust AR, Reisz RR. 2017. The unique preservational environment of the Early Permian (Cisuralian) fossiliferous cave deposits of the Richards Spur locality, Oklahoma. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 475, 1–11. ( 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.02.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reisz RR, MacDougall MJ, Modesto SP. 2014. A new species of the parareptile genus Delorhynchus, based on articulated skeletal remains from Richards Spur, Lower Permian of Oklahoma. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 34, 1033–1043. ( 10.1080/02724634.2013.829844) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Li X-W, Jia S-H, Liu J. 2014. The Jiyuan tetrapod fauna of the Upper Permian of China: new pareiasaur material and the reestablishment of Honania complicidentata. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 60, 689–700. ( 10.4202/app.00035.2013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuji LA. 2017. Mandaphon nadra, gen. et sp. nov., a new procolophonid from the Manda Beds of Tanzania. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 37(Suppl. 1), 80–87. ( 10.1080/02724634.2017.1413383) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox RC. 1962. Two new pelycosaurs from the Lower Permian of Oklahoma. Univ. Kans. Publ. Mus. Nat. Hist. 12, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Modesto SP, Scott DM, Botha-Brink J, Reisz RR. 2010. A new and unusual procolophonid parareptile from the Lower Triassic Katberg Formation of South Africa. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 30, 715–723. ( 10.1080/02724631003758003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuji LA, Sobral G, Müller J. 2013. Ruhuhuaria reiszi, a new procolophonoid reptile from the Triassic Basin of Tazania. C.R. Palevol 12, 487–494. ( 10.1016/j.crpv.2013.08.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bulanov VV, Yashina OV. 2005. Elginiid pareiasaurs of Eastern Europe. Paleontol. J. 39, 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Säilä LK. 2008. The osteology and affinities of Anomoiodon liliensterni, A procolophonid reptile from the Lower Triassic Bundsandstein of Germany. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 1199–1205. ( 10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1199) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X-W, Liu J. 2013. New specimens of pareiasaurs from the Upper Permian Sunjiagou Formation of Liulin, Shanxi and their indication for the taxonomy of Chinese pareiasaurs. Vertebr. Palasiat. 51, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bever GS, Lyson TR, Field DJ, Bhullar B-AS. 2015. Evolutionary origin of the turtle skull. Nature 525, 239–242. ( 10.1038/nature14900) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bever GS, Lyson TR, Field DJ, Bhullar B-AS. 2016. The amniote temporal roof and the diapsid origin of the turtle skull. Zoology 119, 471–473. ( 10.1016/j.zool.2016.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bapst DW. 2012. paleotree: an R package for paleontological and phylogenetic analyses of evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 803–807. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00223.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell MA.2015. geoscale: geological time scale plotting. See https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=geoscale .

- 45.Brusatte SL, Montanari S, Yi H, Norell MA. 2011. Phylogenetic corrections for morphological disparity analysis: new methodology and case studies. Paleobiology 37, 1–22. ( 10.1666/09057.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lloyd GT. 2016. Estimating morphological diversity and tempo with discrete character-taxon matrices: implementation, challenges, progress, and future directions. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 118, 131–151. ( 10.1111/bij.12746) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes M, Gerber S, Wills MA. 2013. Clades reach highest morphological disparity early in their evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13 875–13 879. ( 10.1073/pnas.1302642110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revell LJ. 2012. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bapst DW, Bullock PC, Melchin MJ, Sheets HD, Mitchell CE. 2012. Graptoloid diversity and disparity became decoupled during the Ordovician mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3428–3433. ( 10.1073/pnas.1113870109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foote M. 1994. Morphological disparity in Ordovician–Devonian crinoids and the early saturation of morphological space. Paleobiology 20, 320–344. ( 10.1017/S009483730001280X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holterhoff PF, Baumiller TK. 1996. Phylogeny of the proto-articulates (ampelocrinids + basal articulates): implications for the Permo-Triassic extinction and re-radiation of the Crinoidea. Paleontol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 8, 176 ( 10.1017/S2475262200001787) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foote M. 1996. Ecological controls on the evolutionary recovery of post-Paleozoic crinoids. Science 274, 1492–1495. ( 10.1126/science.274.5292.1492) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGowan AJ. 2004. Ammonoid taxonomic and morphologic recovery patterns after the Permian–Triassic. Geology 32, 665–668. ( 10.1130/G20462.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villier L, Korn D. 2004. Morphological disparity of ammonoids and the mark of Permian mass extinctions. Science 306, 264–266. ( 10.1126/science.1102127) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grossnickle DM, Newham E. 2016. Therian mammals experience an ecomorphological radiation during the Late Cretaceous and selective extinction at the K–Pg boundary. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160256 ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.0256) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foote M. 1991. Morphological and taxonomic diversity in a clade's history: the blastoid record and stochastic simulations. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. Univ. Mich. 28, 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ezcurra MD, Butler RJ. 2018. The rise of the ruling reptiles and ecosystem recovery from the Permo-Triassic mass extinction. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20180361 ( 10.1098/rspb.2018.0361) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedman M. 2010. Explosive morphological diversification of spiny-finned teleost fishes in the aftermath of the end-Cretaceous extinction. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1675–1683. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.2177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruta M, Angielczyk KD, Fröbisch J, Benton MJ. 2013. Decoupling of morphological disparity and taxic diversity during the adaptive radiation of anomodont therapsids. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20131071 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.1071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruta M, Botha-Brink J, Mitchell SA, Benton MJ. 2013. The radiation of cynodonts and the ground plan of mammalian morphological diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20131865 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.1865) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bazzi M, Kear BP, Blom H, Ahlberg PE, Campione NE. 2018. Static dental disparity and morphological turnover in sharks across the end-cretaceous mass extinction. Curr. Biol. 28, 2607–2615.e3. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.093) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jablonski D. 2002. Survival without recovery after mass extinctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8139–8144. ( 10.1073/pnas.102163299) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foote M. 1996. Models of morphological diversification. In Evolutionary paleobiology (eds D Jablonski, DH Erwin, JH Lipps), pp. 62–86. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Romano M, Brocklehurst N, Fröbisch J. 2017. Discrete and continuous character-based disparity analyses converge to the same macroevolutionary signal: a case study from captorhinids. Sci. Rep. 7, 17531 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-17757-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen KM, Finney SC, Gibbard PL, Fan J-X. 2013. The ICS international chronostratigraphic chart. Episodes 36, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brocklehurst N, Ruta M, Müller J, Fröbisch J. 2015. Elevated extinction rates as a trigger for diversification rate shifts: early amniotes as a case study. Sci. Rep. 5, 17104 ( 10.1038/srep17104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study are included in the electronic supplementary material.