Several activities in the European Parliament in Strasbourg bringing together patient, scientific and political communities served to launch the first ever European Obesity Day (EOD) on May 22, 2010 to raise awareness of the need for action at the European level. In the 27 member states of the European Union approximately 60% of adults and 20% of school-age children are overweight or obese, with experts estimating that 150 million adults and 15 million children will be obese by 2010 in the 53 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region [1, 2]. These are challenging figures, and the next years will be a critical period especially for testing our collective ability to limit the spread and impact of obesity.

Obesity is already changing the epidemiology and natural course of many other diseases. One of the most sinister features of childhood obesity is the development of type 2 diabetes [2]. Given that cardiovascular risk markers are already evident in obese children, diabetes will worsen the clinical impact. Fatty liver has long been recognised in association with human obesity, but its significance as a cause of cirrhosis and liver failure in the long term has only recently been appreciated. The same is true for certain types of cancer with proven robust associations with obesity. No wonder that pessimism is setting in influenced by a sense of defeatism. Much is already being done, but our current best is not good enough, and new resources have to be harnessed and exploited. Although the European Parliament and the WHO have repeatedly drawn attention to this problem (fig. 1), the ultimate translation to action is still needed. Undoubtedly, policy makers play a key role in halting the further development of obesity. Whilst having to stand up against the high expectations from the general public as well as health professionals, medical resources are unrealistic to tackle the problem. On the one hand, politicians may need to be ‘compliant’ to the driving forces of the current economic market. Political messages have to counteract the persuasive and seducing voices of the big industrial players. Moreover, public health actions of specific governments will not be looked at until the end of their stay in office. Thus, frequently, the delivery of official documents rather than the evaluation of real health outcomes are prioritised.

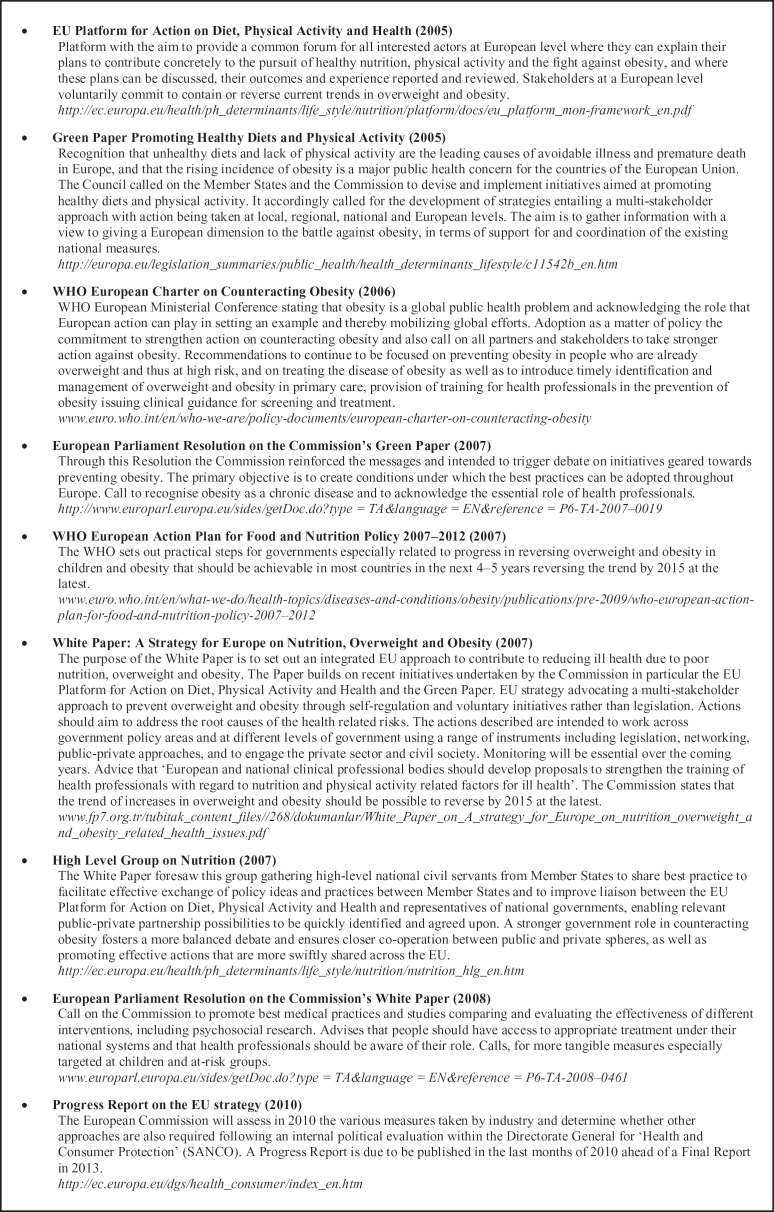

Fig. 1.

Panel summarising key EU and WHO obesity-related policy initiatives in the last years.

The treatment and prevention of obesity remain the thorniest issues and the greatest unmet needs. In purely energetic terms, obesity holds little mystery as it simply represents the excess of energy intake over expenditure. In humans, further layers of complexity to the genetic-environmental interaction are added by the numerous psychological, social and cultural factors that shape eating behaviour and physical activity [3, 4]. However, from a pragmatic point of view it can be argued that we already know enough about obesity to make reasonable attempts to treat the disease. Noteworthy, evidence that weight loss, even if only 5–10%, significantly decreases mortality, improves lipid profile, insulin resistance, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, osteoarthritis as well as other chronic diseases, and decreases the risk for developing cancer is derived from numerous studies carried out decades ago, but also from more recently performed randomised clinical trials such as the US Diabetes Prevention Program, the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, and the Look AHEAD trial etc. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. A 58% reduction in new cases of type 2 diabetes has been observed in the lifestyle intervention groups with weight loss being the dominant predictor of diabetes risk in these groups. For every kilogram of weight loss, diabetes was reduced by 13%. Modest weight loss also reduced the need of diabetes and antihypertensive medication. Analogous results have been obtained with trials of hypertension prevention showing that with even a modest weight loss change a major impact on mortality can be achieved.

Health professionals face a clinical inertia characterised by the lack of attention paid to obesity in the medical curricula [11], failed opportunities for diagnosis in specialised consultation, and the inclination to treat the consequences of obesity without specifically addressing the importance of weight loss [12]. Both food- and activity-related environmental changes are mandatory for any response to support behaviour change. The obesogenic environment should be minimised with changes in transport infrastructure and urban design. Broadly based societal interventions are needed to combat obesity at the same time as stimulating reflection on the potential response of society as a whole. Initiatives that are more likely to affect multiple pathways within the origin of obesity development in a sustainable way should be addressed. Creating demand for such change may rely on aligning the benefits with those arising from broader social and economic goals.

Obesity should be a top priority, with increased political commitment and prioritisation. The summarised evidence highlights the critical need for concerted, coordinated and specific strategies against obesity. The notion of a united front of patients, health professionals, and policy-makers is important, but a truly successful line-up needs to bring in other powerful key players, namely the industrial giants selling food and drink, cars, and screen-based entertainment. We already lost the first battle, which was halting the epidemic in the 21st century. The EOD highlighted that it is worth fighting the next big battle and urges to do so via the ‘European citizens initiative’ [13]. Thanks to the Lisbon Treaty, European citizens have now this new tool to participate in the shaping of EU policy; by collecting signatures from one million citizens, who are nationals of a significant number of Member States, the European Commission can directly be asked to take note and action. Thus, by simply registering one’s support for the EOD charter a stimulus for creating a healthier Europe can be achieved.

Disclosure

The author is President-Elect of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO).

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO): Obesity www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/diseases-and-conditions/obesity.

- 2.Han JC, Lawlor DA, Kimm SYS. Childhood obesity. Lancet. 2010;375:1737–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinney AHebebrand J. Polygenic obesity in humans. Obes Facts. 2008;1:35–42. doi: 10.1159/000113935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WCBarett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuomilehto JLindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindström JParikka PI, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;366:1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakicic JMJaramillo SA, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention on change in cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD Study. Int J Obes. 2009;33:305–316. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson DARejeski J, Lang W, et al. Impact of a weight management program on health-related quality of life in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:163–171. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redmon JBBertoni AG, Connelly S, et al. Effect of the Look AHEAD Study intervention on medication use and related cost to treat cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1153–1158. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall JI. Obesity – a reluctance to treat? Obes Facts. 2010;3:79–80. doi: 10.1159/000304766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frühbeck G, Diez-Caballero A, Gómez-Ambrosi J, et al. Preventing obesity. Doctors underestimate obesity. BMJ. 2003;326:102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Obesity Day (EOD) European Citizens’ Initiative Petition www.obesityday.eu/eu/en/european-citizens-initiative-petition.