Abstract

The genomic predisposition to oncology-drug-induced cardiovascular toxicity has been postulated for many decades. Only recently has it become possible to experimentally validate this hypothesis via the use of patient-specific human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and suitably powered genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Identifying the individual single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) responsible for the susceptibility to toxicity from a specific drug is a daunting task as this precludes the use of one of the most powerful tools in genomics: comparing phenotypes to close relatives, as these are highly unlikely to have been treated with the same drug. Great strides have been made through the use of candidate gene association studies (CGAS) and increasingly large GWAS studies, as well as in vivo whole-organism studies to further our mechanistic understanding of this toxicity. The hiPSC model is a powerful technology to build on this work and identify and validate causal variants in mechanistic pathways through directed genomic editing such as CRISPR. The causative variants identified through these studies can then be implemented clinically to identify those likely to experience cardiovascular toxicity and guide treatment options. Additionally, targets identified through hiPSC studies can inform future drug development. Through careful phenotypic characterization, identification of genomic variants that contribute to gene function and expression, and genomic editing to verify mechanistic pathways, hiPSC technology is a critical tool for drug discovery and the realization of precision medicine in cardio-oncology.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Cardiotoxicity, Pharmacogenomics, hiPSC, Prediction

This article is part of the Spotlight Issue on Cardio-oncology.

1. Introduction

Though the cardiovascular toxicity of many oncology drugs is now well established, a patient’s individual likelihood of experiencing a cardiovascular adverse event (CAE) is difficult to predict despite known risk modifiers such as dose, age, and history of cardiovascular issues such as hypertension.1 The inter-individual variability in the incidence of CAEs that persists even when risk modifiers are taken into account led to the postulation that genomic variants may contribute to this susceptibility.2 Identification of the specific variants that contribute to drug-specific CAE risk is valuable, as this would allow clinicians to screen patients for susceptibility variants prior to treatment and either select an alternative treatment or co-administer protective adjuvant therapy. Identification of variants can also advance our understanding of the mechanisms of these CAEs, which in turn may inform development of modified chemotherapeutics that bypass off-target pathways and/or adjuvant chemoprotective agents.

Because of the importance of identifying variants that confer susceptibility, researchers have invested significant effort in determining the association between specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and CAEs. These efforts have largely focused on candidate gene association studies (CGAS) and, more recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS). While these studies may identify variants that may contribute to drug-specific CAEs, they are unable to offer conclusions regarding causality and are limited in their ability to inform an understanding of mechanism. Furthermore, these studies are often practically limited by small sample sizes that render them underpowered.3,4

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have made it possible to experimentally validate the hypothesis that certain drug-induced CAEs are genetically determined. Through genomic editing, hiPSCs allow for validation of significant variants identified in CGAS and GWAS studies and can be used to discover and validate novel variants.5–7 Functional, genomic, and transcriptomic characterization of hiPSCs and their response to drugs can be used to generate and validate hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of CAEs.8 hiPSCs represent a renewable cell type that can be obtained non-invasively, unlike primary tissues, and bypass the ethical concerns associated with human embryonic stem cells.9 Additionally, they are genetically identical to the patients from whom they are derived, which makes them uniquely suitable for pharmacogenomics research.9 Another advantage of hiPSCs is that they can be obtained from patients after treatment, when it is known whether the patient has developed toxicity, and still be characterized in both pre- and post-drug exposure states. This offers practical advantages over other methods to identify predictors of toxicity, such as cardiac imaging, where patients need to be enrolled before treatment and follow-up may end before longer term toxicities develop.10 For these reasons, hiPSCs are a critical tool for advancing the field of cardio-oncology.

2. Pharmacogenomic determinants of chemotherapy-induced cardiac adverse effects

2.1. Anthracyclines

The majority of the existing pharmacogenomics literature for chemotherapeutics with adverse cardiovascular effects focuses on anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and heart failure. Numerous CGAS related to this topic have been published. Many of these studies were limited by small sample size and identified no significant SNPs.11–22 Among CGAS that identified significant variants, candidate genes were related to drug metabolism (CBR3,23UGT1A6,24,25 and POR26), drug transport (SLC28A3,25,27SLC22A17,28SLC22A7,28ABCC2,29ABCC1,30–32ABCC5,33 and ABCG234), iron metabolism (HFE29,35), cell signalling (RAC2,29,31NOS3,33 and PLCE136), DNA repair (ERCC2,37BRCA1,38 and BRCA238), splicing regulation (CELF424), response to oxidative stress (CAT,39NCF4,31,40,41GSTP1,42 and CYBA31,41), calcium homeostasis (ATP2B136), myosin synthesis (MYH743), and extracellular matrix synthesis (HAS324,44). Additionally, two exome array analyses identified candidate genes (ETFB45 and GPR3546) that were significant only when analysed with a gene-based approach. These significant candidate genes are valuable for generating hypotheses regarding the mechanism of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. However, many of these studies have yet to be replicated and lack experiments that functionally validate identified SNPs. Additionally, the definition of ‘cardiotoxicity’ varied across studies, which limits comparability.

In addition to CGAS, multiple GWAS have been conducted related to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. GWAS offers the advantage of surveying a broader spectrum of the genome in an unbiased manner with the potential to identify novel variants that may not be identified with a CGAS approach. Aminkeng et al.47 published the first GWAS of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity from a cohort of paediatric cancer patients. They identified a significant variant in RARG (rs2229774), a transcription factor that binds the TOP2B promoter. This variant remained significant when replicated in European and non-European cohorts. Wang et al.48 identified a variant in CELF4 (rs1786814), a splicing regulator, that was significant in discovery and replication cohorts for patients who received cumulative anthracycline doses greater than 300 mg/m2. They utilized 33 healthy heart samples to validate the relevance of this variant to differential splicing of the TNNT2 gene. Schneider et al.49 identified 11 candidate variants in a discovery cohort and prioritized two for replication in two independent trials. An intergenic variant rs28714259 had a statistically significant association with decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Todorova et al.50 conducted a GWAS in a small cohort (n = 30) and identified 18 SNPs in nine genes in the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) region, though none met statistical significance. Wells et al.51 identified 11 candidate variants in a discovery cohort. None of these variants were statistically significant in the replication cohort, though a SNP near PRDM2 (rs7542939) approached significance (P = 6.5 × 10−7). The aforementioned GWAS studies discovered novel variants not previously identified through candidate gene approaches, though the use of SNP arrays limits the ability to distinguish between causal candidate variants and those in linkage disequilibrium with causal variants. Future studies with a whole genome sequencing (WGS) approach could partially address this limitation.

2.2. HER2 inhibitors

Multiple CGAS have been conducted to identify variants associated with trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity, and all have identified significant SNPs in ERBB2 (rs113620152–55 and rs105880856,57), though the specific variant varies across studies. ERBB2 is the target of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab and its inhibition is believed to impair cardioprotective pathways.58 A whole-exome association study was conducted that found no significant associations but identified 10 variants below a P-value threshold that were then examined in a replication cohort.59 None of the variants were significant in the replication cohort, though the authors note three variants showed an effect in the same direction as the discovery cohort.59 Only one GWAS of trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity has been published. Serie et al.60 conducted a GWAS in a cohort of patients who received doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by either paclitaxel alone, paclitaxel with subsequent trastuzumab, or paclitaxel with concurrent trastuzumab. In this discovery cohort, they identified six novel candidate loci that were associated with a decreased LVEF in patients who received subsequent or concurrent trastuzumab but not in those who received paclitaxel alone. Significant loci were identified in LDB2, BRINP1, RAB22A, TRPC6, LINC01060, and an intergenic region in chromosome 6. In contrast to the aforementioned CGAS, the authors did not identify a significant SNP in ERBB2.

Newer HER2 pathway inhibitors such as pertuzumab, lapatinib, neratinib, and afatinib have been associated with reduced CAE, though genomic associations remain to be determined.61

2.3. Immunomodulatory agents

Two CGAS have examined the impact of genetic factors on the association between immunomodulators and venous thromboembolism (VTE). In a discovery cohort of patients with myeloma treated with thalidomide, authors identified 120 SNPs associated with thalidomide-induced VTE.62 They then examined two additional cohorts and eliminated any candidate SNPs with a different frequency distribution in these cohorts compared to the discovery cohort. They ultimately identified 18 SNPs in genes involved in drug metabolism, DNA repair, apoptosis, and inflammation. Another CGAS involved a cohort of patients treated with lenalidomide who experienced VTE while on aspirin prophylaxis.63 Authors identified a candidate variant in NFKB1, though the association did not reach statistical significance.

2.4. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor signalling pathway inhibitors

Di Stefano et al.64 investigated the association of a single SNP in the 5′ untranslated region of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) with thrombo-haemorrhagic vascular events in bevacizumab-treated patients. The candidate SNP was chosen based on previous reports implicating this locus in VEGFA expression, tumour risk, and vascular disorders. The authors found that the incidence of vascular events differed by genotype in bevacizumab-treated patients.

Though a number of additional VEGF inhibitors are known to cause CAEs, to date, genomic investigations of these associations are lacking.61

2.5. Future research

While cardiovascular adverse effects of chemotherapeutics are common and include cardiotoxicity, heart failure, arrhythmias, prolongation of the QT interval, hypertension, hypotension, tachycardia, bradycardia, vascular occlusive events, and cardiopulmonary arrest, there are no published pharmacogenomics data for the majority of chemotherapeutics.65 As research into these individual agents progresses, CGAS and GWAS may advance our understanding of inter-individual variability in susceptibility to adverse effects. With the increasing availability and cost-effectiveness of WGS, genome association studies that move beyond genotyping array chips may further increase the likelihood of identifying novel variants. Despite these advances, however, the inability of any of these methods alone to distinguish between correlation and causation necessitates that identified variants undergo functional validation. Additionally, the requisite sample sizes to ensure these investigations are adequately powered will likely remain a practical hindrance for many studies.

3. hiPSCs in pharmacogenomics research

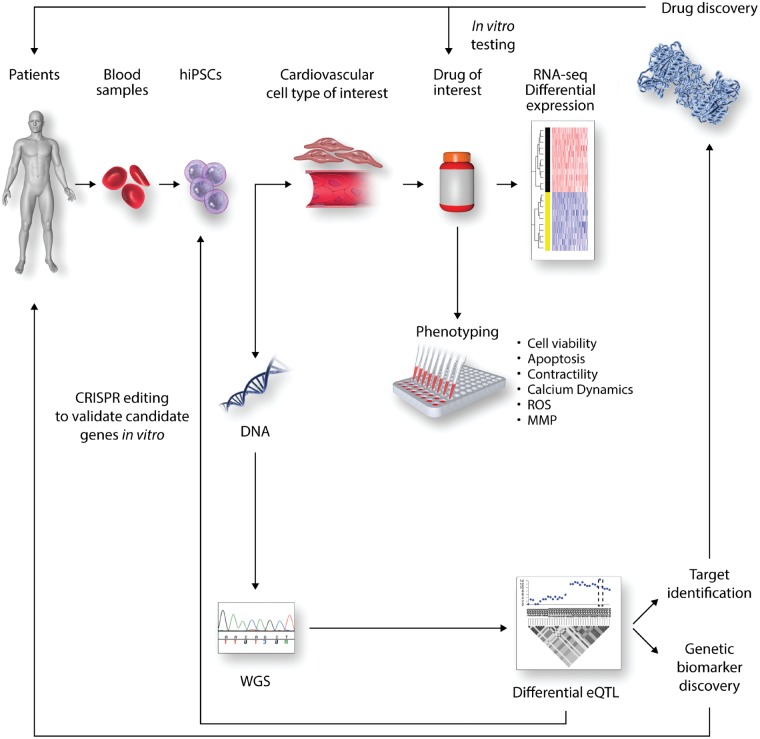

hiPSC technology is uniquely suited to investigating the pharmacogenomics of chemotherapy-induced adverse cardiovascular effects. hiPSCs provide a model with which to identify potential toxicities, examine the mechanism of toxicities, and identify and validate genetic determinants of susceptibility to toxicities.8,66 This information is vital to drug discovery efforts to develop alternative chemotherapeutics and protective adjuvant therapies. A workflow for hiPSC-based translational studies to advance cardio-oncology is shown in Figure 1. hiPSCs are a renewable source of multiple cardiovascular cell types, including cardiomyocytes (CMs), endothelial cells (ECs), and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).9,67,68 This allows for extensive in vitro characterization of tissue-specific human cell lines that would be difficult to obtain and maintain as primary cells.69 Of particular advantage for pharmacogenomics, hiPSCs are genetically identical to the patients from whom they are derived, which allows for genetic characterization and manipulation in vitro that can then be compared with clinical phenotypes.8,9,68

Figure 1.

The role of hiPSCs in genetic biomarker and drug discovery. Blood samples collected from patients of interest can be differentiated into hiPSCs and subsequently differentiated into cardiovascular cell types of interest, such as CMs and ECs. The phenotypic response of these hiPSC derivatives to the drug of interest can be assessed through a variety of assays. Changes in gene expression pre- and post-drug exposure can be analysed with RNA-seq. WGS of DNA extracted from hiPSCs can then be used in combination with the differential transcriptomic data to conduct a differential eQTL analysis. Candidate variants from these studies can then be validated through genomic editing in hiPSCs and re-phenotyping. Validated eQTL variants will establish a foundation for both target identification and genetic biomarker discovery. Genetic biomarkers can be used clinically to screen for patients with a susceptibility to drug-induced CAEs. Identified targets can support drug discovery efforts through drug repurposing, small molecule screens, and in silico screens. Candidate drugs can be tested in vitro to verify that they do not cause CAEs and successful drugs can then be brought to patients through clinical trials.

While hiPSCs and their derivatives offer many advantages, there are limitations associated with hiPSC-derived tissues. With respect to CMs, hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) exhibit a more immature phenotype than adult cardiac cells.70–72 Additionally, differentiation of hiPSC-CMs yields a mixed population of atrial, ventricular, and nodal cells.69,73 Furthermore, hiPSC-derived tissues are typically maintained as a single tissue type, and this may preclude identification of phenotypes that result from interactions among tissues.68

Despite these limitations, hiPSC-CMs have been shown to recapitulate patient-specific adverse effects in response to chemotherapy. Burridge et al.68 collected fibroblasts from patients treated with doxorubicin who did and did not develop doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (DIC) and reprogrammed them to hiPSCs. They then differentiated hiPSC-CMs and extensively characterized cell viability, mitochondrial and metabolic function, calcium handling, antioxidant pathway activity, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production following doxorubicin exposure. For each of these, they found that hiPSC-CMs from patients who experienced DIC were more sensitive to doxorubicin than those from patients who did not experience DIC. They also examined the impact of doxorubicin on patient-specific gene expression by comparing changes in gene expression pre- and post-exposure in patients who did and did not experience DIC. To date, this is the only patient-specific study of chemotherapy-induced CAEs in hiPSC-derived tissues.hiPSC-CMs have also been shown to recapitulate CAEs from non-chemotherapeutics. Shinozawa et al.71 derived hiPSC-CMs from healthy volunteers with differential susceptibility to QT prolongation in response to moxifloxacin treatment. The authors used a multielectrode array (MEA) to measure field potential duration (FPD) as a surrogate for the QT interval. They found that FPD prolongation in vitro was positively correlated with the QT prolongation observed in vivo at clinically relevant concentrations.

Several additional studies have used patient-nonspecific hiPSCs to examine cardiotoxicity and its mechanisms for a variety of chemotherapeutics. Sharma et al.74 differentiated hiPSC-CMs, hiPSC-derived endothelial cells (hiPSC-ECs), and hiPSC-derived cardiac fibroblasts (hiPSC-CFs) from 11 healthy volunteers and two patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) who had not experienced CAEs to examine the potential of 21 TKIs to induce CAEs. In hiPSC-CMs, the authors characterized cytotoxicity, contractility, electrophysiology, calcium handling, and receptor tyrosine kinase signalling in response to TKI exposure and used cytotoxicity and contractility to develop a ‘cardiac safety index’ that correlated with clinical phenotypes. They also examined cytotoxicity of TKIs in hiPSC-ECs and hiPSC-CFs. Finally, they investigated differential gene expression pre- and post-TKI exposure in hiPSC-CMs. This study exemplified the potential of hiPSC-derived cells as a high-throughput platform to screen for the potential of specific drugs to induce CAEs.

Multiple studies have used smaller numbers of patient-nonspecific hiPSC-CM lines to characterize the in vitro response of CMs to drugs associated with CAEs. Hsu et al.75 used four independent hiPSC-CM lines to examine the mechanism of increased DIC in the presence of lapatinib. Other studies have used single hiPSC-CM lines to characterize CAEs caused by doxorubicin,58,76–84 trastuzumab,58,85,86 etoposide,87 arsenic trioxide,84,88,89 TKIs,90–96 and histone deacetylase inhibitors.84,97,98

4. Defining an adverse effect phenotype in vitro

Prior to embarking on pharmacogenomics investigations in hiPSCs, demonstration that the hiPSC-derived cells recapitulate patient-specific toxicity in response to a specific chemotherapeutic is essential. This verifies that the phenotype seen clinically is adequately reproduced by the derived cells and validates that the chosen assays are capable of quantifying these phenotypic differences. Once these conditions are met, cells can be genetically manipulated to investigate the impact of specific variant modifications on the toxicity phenotype.

For this reason, a critical first step in hiPSC-based pharmacogenomics research is to define and validate the assays that will assess the phenotype of interest. Assay development can begin in hiPSC-derived tissues from healthy controls to demonstrate proof of principle and define the dose–response curve for a given chemotherapeutic. Next, hiPSC derivatives from patients treated with the chemotherapeutic of interest who did and did not develop toxicity should be tested with the previously identified assay(s) to verify that the clinical phenotype is recapitulated in the in vitro model.

Among studies that have examined CAEs of chemotherapeutics, a variety of techniques and assays have been implemented with which to characterize CAE phenotypes in hiPSC-derived cells. Cell viability is often of interest in investigations of CAEs, particularly for chemotherapeutics known to cause cardiotoxicity. Many studies employ an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) detection assay, a luminescence assay that lyses cells, inhibits cellular ATPases and uses luciferin and luciferase to generate light.58,68,74,81,91,94,95 ATP measurement is a widely accepted surrogate for viability and linearly correlates with cellular plating density; however, certain levels of toxin exposure have been shown to cause a compensatory increase in ATP production, such that ATP concentrations may misrepresent the number of viable cells present.99 Others have used resazurin-based assays, where a shift in colour and fluorescence occurs when the resazurin is reduced to resorufin, and the degree of shift is proportional to the number of metabolically active viable cells.68,74 Validity of resazurin-based assays is contingent on a consistent relationship between metabolism and viability. If a drug known to cause CAEs alters cardiac cellular metabolism as part of its toxicity, this may confound interpretation of this assay as a readout of viability. Additionally, many chemotherapeutic drugs have inherent fluorescence, which may impact the accuracy of any fluorescence-based assay.100 Water-soluble tetrazolium salt, which changes colour when reduced by cellular dehydrogenases, has also been used as an assay for viability.74,80 An additional technique to assess viability is to perform cell counts exclusive of cells that stain with either trypan blue or propidium iodide, reagents that only permeate dead or dying cells.75,91,93

Studies have also quantified apoptosis and cell death. Luminescent assays to quantify effector caspases in lysed cells have been used in multiple hiPSC CAE studies to measure apoptosis.68,81,90,93,95 Results of such assays should be interpreted with an understanding that caspase activation typically but not always leads to apoptosis.101 Apoptosis can also be detected via flow cytometry in cells stained with 7-aminoactinomycin D and annexin V.68,75 Annexin V binds phosphatidylserine residues that are externalized in early apoptosis, while 7-aminoactinomycin D binds DNA in cells where the nuclear membrane has become permeable due to either late apoptosis or necrosis.102 Cell death and damage can also be quantified via measurement of lactate dehydrogenase, a cytosolic enzyme that is released in settings of membrane damage, with a colorimetric assay.68,79,80,83,85,87,94,95 Assays contingent on membrane permeability capture late stages of apoptosis and may miss more subtle damage or early apoptotic stages. Additionally, they cannot distinguish between membrane permeabilization that results from apoptosis versus necrosis.103 Caution should also be exercised when using colorimetric assays for quantification related to drugs with inherent colour. Doxorubicin, for example, is orange and may confound certain colorimetric assays. The concentration of troponin in cell culture media following chemotherapeutic exposure can also be quantified as a surrogate for CM damage.84,92 This again relies on membrane permeabilization and thus is a measure of late-stage cell damage caused by either apoptosis or necrosis.

Dynamic properties of hiPSC-CM, such as beat rate, beat amplitude, and contractility, may also be informative in investigations of drug-induced CAEs. Several studies have used xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis or Nanion CardioExcyte 96, which both measure beat rate and amplitude in addition to electrical impedance caused by hiPSC-CMs adhesion.58,78,87,90,92,97 This impedance value can be affected by changes in cell morphology, number, or movement, and in drug-induced CAE studies, it is often used to estimate viability.104 This type of analysis has many advantages including real-time, non-invasive, and high-throughput assessment of cells.104 However, given that impedance can be affected by many parameters aside from viability, these data should be corroborated by additional assays.104 Other studies have quantified contractility by analysing data obtained through video microscopy68,84 or a kinetic imaging cytometer.74

Measurement of ROS, as well as activation of antioxidant pathways, may be informative for chemotherapeutics that are believed to cause CAEs at least in part through oxidative stress. Dihydroethidium (DHE) is a fluorescence-based superoxide indicator often used to quantify ROS.87,90,92 DHE is meant to target superoxide, but has limited specificity as other oxidants have been shown to react with DHE, and appropriate controls are necessary to draw quantitative conclusions.105–107 Hydrogen peroxide and oxidized and reduced quantities of the antioxidant glutathione can also be measured with luminescence-based assays to assess oxidative stress in cells.68,95 Oxidative stress is a complex cellular process and thus a difficult parameter to accurately quantify.107 For this reason, multiple assays to assess various facets of oxidative stress and their appropriate controls should be used.107

Other assays may be selected based on specific properties of a chemotherapeutic or its CAE. For example, doxorubicin is known to induce DNA damage, so in vitro studies may use an antibody against phospho-histone y-H2AX to detect this.68 Certain drugs are hypothesized to cause CAEs through mitochondrial toxicity, and a number of assays to characterize mitochondrial function and damage may be appropriate. Mitochondrial superoxide specifically can be detected with the fluorescent dye MitoSOX red, a mitochondrially targeted DHE.68 Additionally, mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis can be measured with an extracellular metabolic flux assay.68,75,91 Mitochondrial membrane potential, which is altered in the early stages of apoptosis, can be quantified with fluorescent dyes that accumulate in mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent manner.68,87

Many drugs, including chemotherapeutics, are known to induce arrhythmias and prolong the QT interval. Drug-induced alterations in electrophysiological properties of hiPSC-CMs can be evaluated in a number of ways. Patch clamping, the gold standard for electrophysiology, has successfully been used to characterize drug reactions in hiPSC-CMs.74,90,96,98 While this method offers high precision, it is low-throughput and requires significant technical expertise. Electrophysiological properties of hiPSC-CMs can also be assessed over a longer duration in a high-throughput manner with a MEA.77,80,89,95,97,108 MEA can measure beat rate and amplitude, as well as FPD, which can serve as a surrogate for action potential (AP) duration.89,95,97 For drugs that cause arrhythmias, information regarding calcium handling may also be of interest, and multiple fluorescent dyes are available that bind to calcium and can thus highlight calcium signalling.68,74,87

Though few hiPSC-based investigations of drug-induced vascular CAEs such as hypertension, peripheral artery disease, and VTE have been reported, a number of assays may aid in the modelling and characterization of these CAEs in vitro. Sharma et al.74 quantified the toxicity of TKIs on hiPSC-ECs in the same manner used for hiPSC-CMs. Kurokawa et al.109 exposed hiPSC-ECs to sunitinib, which resulted in a significant decrease in vascular surface area. Beyond studies of chemotherapy-induced CAEs, common assays for ECs include tube formation, LDL uptake, and nitric oxide production.67,110–115 Multiple studies have used ATP detection assays or caspase assays to characterize viability or apoptosis respectively.113,116,117 Additionally, monolayers of ECs can be scratched to characterize proliferation.114,118 Investigators have also used the xCELLigence system to identify formation of a tight monolayer as indicated by impedance and found that addition of thrombin or inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), VEGFA, and IL-1β disrupted barrier function and thus decreased impedance.67,117 Other elements of the response of hiPSC-ECs to inflammatory cytokines can be assessed via cellular tethering assays and ICAM1 expression.67,117 Similar to investigations of hiPSC-CMs, oxidative stress has also been characterized in hiPSC-ECs.115

VSMCs participate in multiple vascular CAE phenotypes such as atherosclerosis and hypertension.119,120 While no studies to date have characterized hiPSC-derived VSMCs (hiPSC-VSMCs) with respect to chemotherapy-induced CAEs, studies of hiPSC-VSMCs for other applications can provide insights regarding potential assays that may be useful for such studies in the future. Contractile potential of VSMCs can be quantified by imaging the response of cells to a contractile stimulus. Various protocols exist for staining either whole cells or vinculin, actin, and calcium specifically.67,119,121,122 Most commonly carbachol, but also angiotensin II, endothelin 1, or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, can then be added and time-lapse microscopy can capture the percentage of contracting cells, change in cell length, and the percent change in surface area upon contraction.67,119,121,122 Biel et al.119 used traction force microscopy and specialized hydrogels with embedded fluorescent beads to compare bead movement between attached and unattached cellular conditions with and without endothelin-1 in the media to calculate strain energy as a surrogate for contractility. Other investigators have conducted hiPSC-VSMC tube-forming assays with or without co-culture with ECs.121,122

As most vascular CAEs, such as atherosclerosis and hypertension, involve inflammatory pathways, quantification of changes in gene expression in response to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α may be informative to characterize VSMCs in vitro.119,121 Because matrix metalloproteases are implicated in atherogenesis, elastin and collagen degradation assays may also be performed following cytokine exposure.121 In atherosclerosis, VSMCs are believed to switch from contractile to synthetic phenotypes, and these phenotypes can be distinguished through multiple assays.123,124 Synthetic VSMCs show increased migration in response to a scratch test and increased proliferation, which can be measured using a tetrazolium-based colorimetric proliferation assay, cell counts, or Ki67 immunostaining.124,125 Synthetic VSMCs also exhibit decreased contractility in response to carbachol exposure.124 Fibronectin deposition with and without TGF-β exposure may also be informative.67

5. hiPSCs to investigate mechanisms of cardiovascular adverse effects

Understanding the mechanism of drug-induced cardiovascular adverse effects is important for interpreting the significance of candidate variants identified in pharmacogenomics studies. An understanding of mechanism allows for assessment of the biological plausibility that a candidate variant would confer susceptibility to or protection from drug-induced adverse effects. This assessment is necessary to determine whether a variant identified in GWAS, for example, is the causal variant or simply in linkage disequilibrium with the causal variant. This is of particular importance for pharmacogenomics where one of the most powerful tools in genomics, the comparison of genotype–phenotype differences among relatives, is unlikely to be feasible unless family members have all been treated with the same medication. Identification of the mechanism of CAEs may also allow for development of novel targeted therapeutics that bypass toxicity pathways and/or development of adjuvant protective therapeutics to offset chemotherapy-induced CAEs.

Some clues to the mechanism of drug-induced CAEs may lie in the specific type of CAE caused by a particular drug. We compiled a list of chemotherapeutics from the National Cancer Institute and examined United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug listings for each agent.65 Among agents that cause either arterial or VTE, many are known to interact with angiogenesis and the coagulation cascade. For example, a number of TKIs are known to cause thrombotic events and also act on vascular system kinases such as VEGF receptors.126 Selective oestrogen receptor modulators are also among cancer therapies that cause thromboembolism, and the impact of oestrogen on haemostatic parameters is well established.127 Other chemotherapeutics that cause thrombotic events, such as ramucirumab and bevacizumab, were specifically designed to impair angiogenesis in tumour cells, so it is unsurprising that they adversely impact the vascular system.128 Of interest, almost none of the cancer therapies known to cause either arterial or VTE are reported to cause arrhythmias, suggesting that agents that cause arrhythmia are operating through distinct pathways from those that cause thrombosis.65 Similarly, only carfilzomib, a proteasome inhibitor, causes both cardiotoxicity and thromboembolism, which suggests that, in general, the mechanisms of cardiac cytotoxicity are distinct from those involved in vascular complications.65 These trends are useful for generating hypotheses regarding CAE mechanisms that can then be validated.hiPSCs are a valuable platform with which to test hypotheses regarding the mechanism of drug-induced CAEs. Much of the hiPSC-based drug-induced-CAE research to date has focused on quantifying the impact of the drug with respect to alterations in viability, oxidative stress, contractility, and others as described above. While these parameters provide vague insight into the mechanism of drug-induced CAEs, such as oxidative stress or alterations in calcium signalling, much work remains to be done with respect to identifying the step-by-step causal pathways that lead from drug exposure to CAEs.

Doxorubicin exemplifies the complex mechanisms involved in chemotherapy-induced CAEs and demonstrates how the gap between characterization of the effects of a drug in vitro and identification of its mechanism hinder drug discovery efforts. For example, oxidative stress has consistently been implicated in the mechanism of DIC.129 A role for oxidative stress has been demonstrated by many studies, including those with hiPSC-CMs that show increases in ROS with doxorubicin exposure that are more substantial in patients who experienced DIC than in those who did not.68 However, multiple clinical trials of antioxidants and free radical scavengers as adjuvant cardioprotective therapy in anthracycline-treated were without success.130,131 This implies that oxidative stress is not the sole driver of DIC, as efforts to reduce oxidative stress are not sufficient for prevention.

Similarly, binding of iron by anthracyclines and resultant oxidative stress have been hypothesized to drive DIC. This idea is supported in part by the clinical utility of the FDA-approved cardioprotectant dexrazoxane for DIC.132 It was thought that the cardioprotectant effect of dexrazoxane, an iron chelator, may derive from competition with anthracyclines for iron binding and a consequent decrease in oxidative stress.132 However, no protective effect has been observed with other iron chelators, which suggests that while iron-anthracycline binding may be involved in the mechanism of DIC, its specific role is not sufficiently well understood to tailor therapy and drug design.133–135

While doxorubicin has multiple adverse effects that have been well characterized, failed drug discovery efforts suggested that multiple pathways were involved and implicated as an upstream mediator of DIC. The key anti-cancer mechanism of anthracyclines such as doxorubicin is topoisomerase 2 inhibition.136 Two isozymes of topoisomerase 2, TOP2α and TOP2β, are present in humans.137,138 TOP2α has increased expression in proliferating cells and its inhibition is believed to be key to doxorubicin’s anti-cancer activity; TOP2β, in contrast, is prominent in quiescent cells such as human cardiac tissue.136–138 Lyu et al.139 examined the role of TOP2β using TOP2β knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and found that knockout MEFs had reduced DNA damage upon anthracycline exposure compared to untreated wild-type MEFs. They also found that dexrazoxane led to rapid degradation of TOP2β, which may potentially explain the mechanism of its cardioprotective effect beyond iron chelation.139 Zhang et al.140 tested the TOP2β hypothesis in a mouse model where they compared the impact of doxorubicin in mice with and without CM-specific deletion of TOP2β. They observed that mice without TOP2β expression in the heart experienced minimal cardiotoxicity with doxorubicin treatment compared to wild-type mice.140 They compared transcriptomic data from the two mice groups and found that mice with the TOP2β deletion had decreased expression of genes involved in cell death pathways and increased expression of genes involved in antioxidant pathways.140 This led them to conclude that TOP2β inhibition is a key upstream mediator of DIC.140 This study identified a single target that is responsible for multiple downstream effects of doxorubicin, including apoptosis, increased ROS, and mitochondrial toxicity.140

Studies such as those by Lyu et al.139 and Zhang et al.140 are crucial for defining mechanistic pathways of chemotherapy-induced CAEs. The TOP2β hypothesis demonstrates the importance of identifying upstream mediators of CAEs, as drug discovery efforts aimed at inhibition of downstream mediators, such as oxidative stress pathways, may not be sufficient to counteract CAEs. Similar studies can be conducted in hiPSC-derived cells through genomic modifications to hypothesized targets, such as TOP2β knockout, and analysis of gene expression data through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).68 Furthermore, hiPSCs offer the advantage of a high-throughput platform that bypasses complications introduced by interspecies studies.9,74 Analysis of transcriptomic data from hiPSC derivatives from patients with and without CAEs can also provide a foundation for hypothesis generation, as transcripts that are differentially expressed between patients with and without CAEs upon drug exposure may provide clues to the mechanistic pathways involved. hiPSC systems then allow for the validation of these hypotheses through genomic editing.

6. Genetic manipulation of hiPSCs

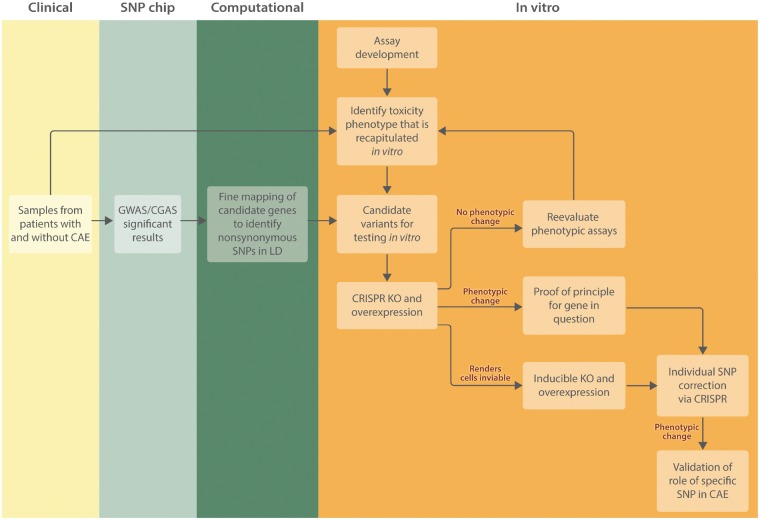

Candidate variants can be validated in vitro with genome editing to further investigate genetic, molecular, and cellular aspects of patient-specific CAEs (Figure 2). Verification that alteration of a putative causal variant alters the phenotypic response in hiPSC derivatives validates the role of that particular variant in CAE susceptibility. Genome editing can also be used to probe mechanistic pathways by identifying the impact of genomic alterations. Genome editing technology has advanced in recent years with engineered nucleases, which allow genes to be modified by introducing targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) that in turn stimulate endogenous repair mechanisms.141,142 Earlier targeted nuclease systems include zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) that utilize specific DNA binding motifs to direct the endonuclease enzyme FokI.143,144 The most recent and widely adapted genome editing technique in basic science research is clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), which involves the DNA cleavage CRISPR associated enzyme 9 (Cas9) and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs Cas9 to the appropriate genome location.142,145 When a DNA DSB results from genome editing, two intrinsic repair mechanisms can occur: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology directed repair (HDR). NHEJ can be used to knock down a gene because it is an efficient yet an error prone repair pathway that can result in small inserts and deletions (INDELs). INDELs within a coding region of a gene can lead to frameshift mutations and loss of function by creating a premature stop codon. HDR, in contrast, provides precise gene editing when a homologous repair template is present and therefore can be used to insert or correct a variant or insert a transgene at the SNP level.142,146 While HDR approaches allow more precise genomic editing, efficiency is often lower than with an NHEJ approach.5 The CRISPR/Cas9 technique for genome editing has been widely adopted due to its ease of use and high specificity.147

Figure 2.

Workflow for validation of candidate chemotherapy-induced CAE variants. Blood samples from patients treated with a specific chemotherapeutic who did and did not experience a specific CAE are collected. These samples can be used with a SNP chip for CGAS or GWAS studies and differentiated to hiPSCs and hiPSC derivatives to define the CAE phenotype in vitro. Assays can be developed before acquisition of patient samples using generic hiPSC derivatives to define the dose-response curve. Genes with variants identified in GWAS or CGAS should undergo fine mapping, either through sequencing of the gene or imputation, to identify nonsynonymous SNPs that were not assessed by the SNP chip but have potential to be the causal variant. The candidate variants identified through the GWAS/CGAS and subsequent fine mapping can then be tested in vitro. CRISPR/Cas9 technology can be used to knockout and overexpress the entire gene. A phenotypic change at this level validates the involvement of some variant within that gene in the CAE phenotype. If no phenotypic change is observed, it may be necessary to re-evaluate the phenotypic assays to ensure the assay captures the impact of the gene of interest in the mechanism. In some cases, a CRISPR/Cas9 knockout will render cells inviable, in which case an inducible knockout that is activated later in differentiation can be used. The final step is CRISPR/Cas9 editing at the SNP level to identify which SNP in a gene is causal.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology offers significant versatility and precise control of genomic conditions. Doxycycline-inducible CRISPR/Cas9 systems, which allow an investigator to control when expression of a specific gene is activated, have been successfully implemented in hiPSCs.148,149 CRISPR/Cas9 technology can also be used to induce gene overexpression through insertion at the AAVS1 safe harbour locus. The AAVS1 locus was identified in human embryonic stem cell lines and is well-suited to overexpression studies due to efficient integration, ubiquitous expression, and resistance to transgene silencing.150 The function of the AAVS1 locus is the same in hiPSCs and multiple studies have taken advantage of this principle to induce overexpression of genes of interest.151,152 The versatility in genome editing through targeted nucleases such as CRISPR/Cas9 makes hiPSCs a powerful tool for studying drug-induced CAEs.

In pharmacogenomic studies of chemotherapy-induced CAEs, it is crucial to discern a causative variant from the genetic background of the patient. The CRISPR/Cas9 system provides scientists with a tool to create hiPSC isogenic controls by introducing targeted mutations in a cell line that can then be compared to the unmodified line.153–155 This technique can be used to induce a phenotype via introduction of variants into control hiPSCs, especially if patient samples are difficult to obtain. Additionally, where samples from affected patients are available, variants can be corrected to determine if this results in phenotypic improvement in response to drug exposure. Although there are currently limited studies utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 to investigate drug-induced CAEs in hiPSC-CM models, studies of inherited cardiovascular disease using CRISPR/Cas9 in hiPSC-CMs demonstrate the feasibility of genome editing in this model. Since inherited cardiovascular diseases often involve a known variant, investigators have demonstrated that patient lines successfully recapitulate the disease phenotype, which can subsequently be rescued with genome editing.

Inherited arrhythmias have been successfully recapitulated at the cellular level in hiPSC-CM models in diseases such as Brugada syndrome (BrS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and long QT syndrome (LQTS).156 Liang et al.157 investigated type 1 BrS, an arrhythmic disorder, using two patient hiPSC lines, each with a different sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 (SCNA5) variant, and two control hiPSC lines. BrS lines showed reduced inward sodium current density, reduced AP maximal upstroke velocity, abnormal calcium transients, and varied beating intervals compared to control lines. Using CRISPR/Cas9, they corrected the causative SCN5A variant (rs397514446) for one patient line and showed that the correction improved maximal upstroke velocity, decreased interval peak to peak variability, and produced normal calcium transients. Two additional studies investigated calmodulinopathies, which are associated with LQTS, CPVT, and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF), and can lead to life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Calmodulinopathies are caused by a missense mutation in one of the three calmodulin (CaM) genes (CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3), which encode the ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor, CaM.158,159 Limpitikul et al.160 used hiPSCs derived from a patient with D130G-CALM2-mediated LQTS to demonstrate a cellular LQTS phenotype of prolonged AP using a genetically encoded voltage sensor, disrupted calcium cycling using a genetically encoded calcium sensor, and diminished inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) using whole-cell patch clamp. They then used CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to downregulate both the variant and wild-type allele of the CALM2 gene while not altering the expression of the other two CALM genes. By suppressing expression of CALM2, they demonstrated rescue of the LQTS phenotype with the normalization of AP and LTCC inactivation in CRISPRi D130G-CALM2 hiPSC-CMs. Yamomoto et al.161 performed a similar study using N98S-CALM2 hiPSC-CMs and demonstrated the LQTS phenotype with prolonged AP impaired and LTCC inactivation using patch clamp. They then used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce INDELs to ablate the CALM2 variant allele and demonstrated rescue of the abnormal electrophysiological phenotypes observed previously.

Beyond inherited arrhythmias, CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to further investigate hiPSC-CM disease models of Barth Syndrome,162 titin mutations associated with dilated cardiomyopathy,163 abetalipoproteinaemia,164 which leads to cardiomyopathy in some patients, and PRKAG2 gene mutations,165 which causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and familial Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

The potential for applying this same approach in studies of drug-induced CAEs was demonstrated by Maillet et al.166 who probed the role of TOP2B in DIC using control hiPSC-CMs. Using CRISPR/Cas9 to disrupt TOP2B, they saw decreased sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced DSB and cell death, further validating the mechanistic role of TOP2B in DIC. Future drug-induced CAEs hiPSC studies will benefit from combining cellular phenotypes, pharmacogenomic analysis, and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to further validate the role of individual SNPs in CAEs.

7. Differential eQTL analysis in hiPSCs

In addition to their utility for validating previously conducted genomic association studies, hiPSCs provide a platform for discovery of novel variants related to both protein function and gene expression. GWAS holds promise for identifying variants that contribute to disease, but many of the significant variants identified in GWAS studies, in particular those in intergenic or intronic regions, have unclear mechanistic interpretations.167,168 This led to an interest in linking genomic and mRNA expression data to identify loci that regulate gene expression, which have been termed expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL).167,168 eQTL analyses have been conducted in a variety of cohorts, tissues, and cell types, including hiPSCs.169 DeBoever et al.169 employed WGS and RNA-seq to conduct an eQTL analysis in 215 hiPSC lines from different donors. To assess the suitability of hiPSCs as a platform for eQTL analysis, they compared hiPSCs to tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) bank, which had previously been used for eQTL analyses, and found that they were similarly powered to detect eQTLs.169,170 They identified candidate variants believed to be involved in transcription factor binding and then performed experimental validation studies.169 They also examined the impact of copy number variation and rare variants on gene expression.169 Carcamo-Orive et al.171 utilized an eQTL approach in a cohort of 317 hiPSCs derived from 101 individuals to identify variants that contribute to differences in gene expression across lines.eQTL analysis has also been conducted in hiPSC-derived tissues. Pashos et al.5 generated hiPSCs from 91 individuals and differentiated them into hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs). They performed eQTL analysis of the hiPSCs, HLCs, and GTEx whole-liver samples and then validated lead variants using genomic editing in cellular and mouse models.5 Through these techniques they identified multiple genes with causal impacts on lipid metabolism.5 The authors note an advantage of hiPSC-based eQTL studies is the ability to identify candidate variants and validate them through genome editing in the same system, without the variability introduced by validating candidates from human tissue studies in animal models.5 This study demonstrates the utility of hiPSC-derived tissues, which are patient-specific and more accessible than human tissue samples, for eQTL analyses. The immaturity of the hiPSC-derived cells is a limitation in these analyses, as demonstrated by discrepancies between HLCs and primary hepatocytes.5 Discrepancies in expression profiles were also seen between primary hepatocytes and liver tissue, which highlights the advantage of hiPSC-derived cells of a single tissue type to clarify the cell-type specific effect of variants on gene expression.5 Warren et al.6 obtained peripheral blood cells to create hiPSC lines from 68 participants with and without a SNP identified in previous eQTL studies to be protective with respect to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol production. They differentiated the hiPSCs to white adipocytes and HLCs and successfully replicated the previous eQTL in addition to identifying novel trans-eQTLs.6 They then used CRISPR/Cas9 editing to remove the protective SNP and observed increases in lipid accumulation and changes in gene expression, thus validating the causal role of this SNP in lipid metabolism.6

The above studies demonstrate the utility of both hiPSCs and hiPSC-derived tissues to conduct and validate eQTL studies in vitro. The potential of this model with respect to drug-induced adverse events is even more significant. hiPSCs and their derivatives can be obtained from patients who did and did not experience a drug-induced adverse event and used to profile the differences in gene expression before and after exposure to a drug. This allows for a differential eQTL analysis to identify SNPs causatively associated with drug-induced adverse events. Though not an eQTL analysis, Hildebrandt et al.36 conducted RNA-seq experiments in hiPSC-CMs following a CGAS and found anthracycline-dependent gene expression for the candidate genes identified in the CGAS analysis. While this was a small study to functionally validate a candidate variant, it demonstrates the principle of studying drug-induced changes in gene expression to identify genetic determinants of susceptibility. Knowles et al.7 differentiated hiPSC-CMs from 45 individuals and examined the transcriptional response to various concentrations of doxorubicin exposure. The majority of genes showed a transcriptional response to doxorubicin exposure, and this varied non-linearly with dose.7 They identified 447 eQTLs that contributed to differential transcriptomic response to doxorubicin across individuals and 42 that contributed to alternative splicing.7 They also found that the variation across lines in doxorubicin-induced changes in gene expression was predictive of the degree of cellular damage.7 The gene expression data observed by Knowles et al.7 showed concordance with that reported previously by Burridge et al.68

Burridge et al.68 examined gene expression in hiPSC-CMs exposed to various concentrations of doxorubicin and also compared changes in gene expression with doxorubicin exposure in hiPSC-CMs from patients who did and did not experience DIC. With increasing doxorubicin doses, they observed downregulation of multiple genes that encode transcription factors for cardiac development pathways.68 A machine-learning approach to the data identified differential expression by dose of additional transcription factor regulators previously implicated in DIC.68 Between hiPSC-CMs from patients with and without DIC they found differences in gene expression for multiple genes previously implicated in DIC.68

The ability to compare gene expression in hiPSC derivatives both across patients and exposures in conjunction with WGS data makes differential eQTL a powerful tool for identifying causal variants and expands the potential of hiPSCs in pharmacogenomics beyond validation of CGAS and GWAS studies to a platform for both discovery and validation of genetic variants that contribute to drug-induced CAEs.

8. Conclusions and future directions

Chemotherapy-induced CAEs are a common and growing concern for cancer patients and their healthcare providers. For many drugs with well-documented toxicity, such as doxorubicin, their effectiveness in cancer treatment and the lack of alternatives justifies their continued clinical use despite known CAEs. For chemotherapeutics where alternative treatments with different CAE risk profiles are available, such as TKIs, susceptibility is often identified only after an irreversible CAE has occurred, as we do not currently have the tools to predict which patients are susceptible. Taken together, the lack of alternatives and inability to predict susceptibility underscore the need for drug discovery and predictive precision medicine tools to decrease the incidence of chemotherapy-induced CAEs.hiPSC models are uniquely and powerfully suited to these aims, as they can be used both to identify and validate causal genetic variants that contribute to CAE susceptibility and elucidate the mechanism of drug-induced toxicities. This information can inform clinical recommendations for genetic testing to identify patients who are at risk of toxicity in response to a specific drug and allow clinicians to prescribe alternative treatment when available. Additionally, mechanistic understanding of these toxicities can inform drug discovery efforts, both for modified chemotherapeutics and adjuvant chemoprotectants, which may be accomplished through drug repurposing, small molecule libraries, and/or in silico screens. Identified compounds can then be tested in hiPSC-based models to verify that they bypass toxicity pathways.66 hiPSC-CMs are beginning to be incorporated into the drug discovery pipeline for many compounds to screen for CAEs, as traditional pre-clinical models have missed many CAEs that were later discovered in post-marketing studies.70

Through careful phenotypic characterization, identification of genomic variants that contribute to gene function and expression, and genomic editing to verify mechanistic pathways, hiPSC technology is a critical tool for drug discovery and the realization of precision medicine in cardio-oncology.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH NCI grant R01 CA2200002, American Heart Association Transformational Project Award 18TPA34230105, a Dixon Translational Research Grants Innovation Award, and the Fondation Leducq (P.W.B.).

References

- 1. Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, Lanzetta G, D'Ascenzo F, Malavasi V, Peruzzi M, Frati G, Palazzoni G.. Review and meta-analysis of incidence and clinical predictors of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1980–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magdy T, Burridge PW.. The future role of pharmacogenomics in anticancer agent-induced cardiovascular toxicity. Pharmacogenomics 2018;19:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colhoun HM, McKeigue PM, Davey Smith G.. Problems of reporting genetic associations with complex outcomes. Lancet 2003;361:865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hewitt JK. Editorial policy on candidate gene association and candidate gene-by-environment interaction studies of complex traits. Behav Genet 2012;42:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pashos EE, Park Y, Wang X, Raghavan A, Yang W, Abbey D, Peters DT, Arbelaez J, Hernandez M, Kuperwasser N, Li W, Lian Z, Liu Y, Lv W, Lytle-Gabbin SL, Marchadier DH, Rogov P, Shi J, Slovik KJ, Stylianou IM, Wang L, Yan R, Zhang X, Kathiresan S, Duncan SA, Mikkelsen TS, Morrisey EE, Rader DJ, Brown CD, Musunuru K.. Large, diverse population cohorts of hiPSCs and derived hepatocyte-like cells reveal functional genetic variation at blood lipid-associated loci. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20:558–570 e510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren CR, O’Sullivan JF, Friesen M, Becker CE, Zhang X, Liu P, Wakabayashi Y, Morningstar JE, Shi X, Choi J, Xia F, Peters DT, Florido MHC, Tsankov AM, Duberow E, Comisar L, Shay J, Jiang X, Meissner A, Musunuru K, Kathiresan S, Daheron L, Zhu J, Gerszten RE, Deo RC, Vasan RS, O’Donnell CJ, Cowan CA.. Induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation enables functional validation of GWAS variants in metabolic disease. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20:547–557 e547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knowles DA, Burrows CK, Blischak JD, Patterson KM, Serie DJ, Norton N, Ober C, Pritchard JK, Gilad Y.. Determining the genetic basis of anthracycline-cardiotoxicity by molecular response QTL mapping in induced cardiomyocytes. Elife 2018;7:e33480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Magdy T, Burmeister BT, Burridge PW.. Validating the pharmacogenomics of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: what is missing? Pharmacol Ther 2016;168:113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Musunuru K, Sheikh F, Gupta RM, Houser SR, Maher KO, Milan DJ, Terzic A, Wu JC; American Heart Association Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing . Induced pluripotent stem cells for cardiovascular disease modeling and precision medicine: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med 2018;11:e000043.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muehlberg F, Funk S, Zange L, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Blaszczyk E, Schulz A, Ghani S, Reichardt A, Reichardt P, Schulz-Menger J.. Native myocardial T1 time can predict development of subsequent anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail 2018;5:620–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blanco JG, Leisenring WM, Gonzalez-Covarrubias VM, Kawashima TI, Davies SM, Relling MV, Robison LL, Sklar CA, Stovall M, Bhatia S.. Genetic polymorphisms in the carbonyl reductase 3 gene CBR3 and the NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene NQO1 in patients who developed anthracycline-related congestive heart failure after childhood cancer. Cancer 2008;112:2789–2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chugh R, Griffith KA, Davis EJ, Thomas DG, Zavala JD, Metko G, Brockstein B, Undevia SD, Stadler WM, Schuetze SM.. Doxorubicin plus the IGF-1R antibody cixutumumab in soft tissue sarcoma: a phase I study using the TITE-CRM model. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1459–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reichwagen A, Ziepert M, Kreuz M, Godtel-Armbrust U, Rixecker T, Poeschel V, Reza Toliat M, Nurnberg P, Tzvetkov M, Deng S, Trumper L, Hasenfuss G, Pfreundschuh M, Wojnowski L.. Association of NADPH oxidase polymorphisms with anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in the RICOVER-60 trial of patients with aggressive CD20(+) B-cell lymphoma. Pharmacogenomics 2015;16:361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinbolt RE, Patel R, Pan X, Timmers CD, Pilarski R, Shapiro CL, Lustberg MB.. Risk factors for anthracycline-associated cardiotoxicity. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2173–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vivenza D, Feola M, Garrone O, Monteverde M, Merlano M, Lo Nigro C.. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the glutathione S-transferase Mu, Pi and Theta gene polymorphisms in cardiotoxicity after anthracycline chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. Int J Biol Markers 2013;28:336–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barac A, Lynce F, Smith KL, Mete M, Shara NM, Asch FM, Nardacci MP, Wray L, Herbolsheimer P, Nunes RA, Swain SM, Warren R, Peshkin BN, Isaacs C.. Cardiac function in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with history of breast cancer treated with anthracyclines. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;155:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cascales A, Sanchez-Vega B, Navarro N, Pastor-Quirante F, Corral J, Vicente V, de la PFA.. Clinical and genetic determinants of anthracycline-induced cardiac iron accumulation. Int J Cardiol 2012;154:282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cascales A, Pastor-Quirante F, Sanchez-Vega B, Luengo-Gil G, Corral J, Ortuno-Pacheco G, Vicente V, de la Pena FA.. Association of anthracycline-related cardiac histological lesions with NADPH oxidase functional polymorphisms. Oncologist 2013;18:446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lubieniecka JM, Liu J, Heffner D, Graham J, Reid R, Hogge D, Grigliatti TA, Riggs WK.. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in aldo-keto and carbonyl reductase genes are not associated with acute cardiotoxicity after daunorubicin chemotherapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:2118–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pearson EJ, Nair A, Daoud Y, Blum JL.. The incidence of cardiomyopathy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers after anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;162:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salanci BV, Aksoy H, Kiratli PÖ, Tülümen E, Güler N, Öksüzoglu B, Tokgözoğlu L, Erbaş B, Alikaşifoğlu M.. The relationship between changes in functional cardiac parameters following anthracycline therapy and carbonyl reductase 3 and glutathione S transferase Pi polymorphisms. J Chemother 2012;24:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vinodhini MT, Sneha S, Nagare RP, Bindhya S, Shetty V, Manikandan D, Ganesan P, Sagar TG, Ganesan TS.. Evaluation of a polymorphism in MYBPC3 in patients with anthracycline induced cardiotoxicity. Indian Heart J 2018;70:319–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blanco JG, Sun CL, Landier W, Chen L, Esparza-Duran D, Leisenring W, Mays A, Friedman DL, Ginsberg JP, Hudson MM, Neglia JP, Oeffinger KC, Ritchey AK, Villaluna D, Relling MV, Bhatia S.. Anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy after childhood cancer: role of polymorphisms in carbonyl reductase genes—a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1415–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leger KJ, Cushing-Haugen K, Hansen JA, Fan W, Leisenring WM, Martin PJ, Zhao LP, Chow EJ.. Clinical and genetic determinants of cardiomyopathy risk among hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Visscher H, Ross CJ, Rassekh SR, Sandor GS, Caron HN, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Rogers PC, Rieder MJ, Carleton BC, Hayden MR, Consortium C.. Validation of variants in SLC28A3 and UGT1A6 as genetic markers predictive of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1375–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lubieniecka JM, Graham J, Heffner D, Mottus R, Reid R, Hogge D, Grigliatti TA, Riggs WK.. A discovery study of daunorubicin induced cardiotoxicity in a sample of acute myeloid leukemia patients prioritizes P450 oxidoreductase polymorphisms as a potential risk factor. Front Genet 2013;4:231.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Visscher H, Ross CJ, Rassekh SR, Barhdadi A, Dube MP, Al-Saloos H, Sandor GS, Caron HN, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Brown AM, Rogers PC, Phillips MS, Rieder MJ, Carleton BC, Hayden MR; Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety Consortium. Pharmacogenomic prediction of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Visscher H, Rassekh SR, Sandor GS, Caron HN, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Rogers PC, Rieder MJ, Carleton BC, Hayden MR, Ross CJ; CPNDS Consortium. Genetic variants in SLC22A17 and SLC22A7 are associated with anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. Pharmacogenomics 2015;16:1065–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Armenian SH, Ding Y, Mills G, Sun C, Venkataraman K, Wong FL, Neuhausen SL, Senitzer D, Wang S, Forman SJ, Bhatia S.. Genetic susceptibility to anthracycline-related congestive heart failure in survivors of haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 2013;163:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vulsteke C, Pfeil AM, Maggen C, Schwenkglenks M, Pettengell R, Szucs TD, Lambrechts D, Dieudonne AS, Hatse S, Neven P, Paridaens R, Wildiers H.. Clinical and genetic risk factors for epirubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wojnowski L, Kulle B, Schirmer M, Schluter G, Schmidt A, Rosenberger A, Vonhof S, Bickeboller H, Toliat MR, Suk EK, Tzvetkov M, Kruger A, Seifert S, Kloess M, Hahn H, Loeffler M, Nurnberg P, Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Brockmoller J, Hasenfuss G.. NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphisms are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation 2005;112:3754–3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Semsei AF, Erdelyi DJ, Ungvari I, Csagoly E, Hegyi MZ, Kiszel PS, Lautner-Csorba O, Szabolcs J, Masat P, Fekete G, Falus A, Szalai C, Kovacs GT.. ABCC1 polymorphisms in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Cell Biol Int 2012;36:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krajinovic M, Elbared J, Drouin S, Bertout L, Rezgui A, Ansari M, Raboisson MJ, Lipshultz SE, Silverman LB, Sallan SE, Neuberg DS, Kutok JL, Laverdiere C, Sinnett D, Andelfinger G.. Polymorphisms of ABCC5 and NOS3 genes influence doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pharmacogenomics J 2016;16:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Megías-Vericat JE, Montesinos P, Herrero MJ, Moscardó F, Bosó V, Rojas L, Martínez-Cuadrón D, Hervás D, Boluda B, García-Robles A, Rodríguez-Veiga R, Martín-Cerezuela M, Cervera J, Sendra L, Sanz J, Miguel A, Lorenzo I, Poveda JL, Sanz MÁ, Aliño SF.. Impact of ABC single nucleotide polymorphisms upon the efficacy and toxicity of induction chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2017;58:1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Kutok JL, Miller TL, Colan SD, Neuberg DS, Stevenson KE, Fleming MD, Sallan SE, Franco VI, Henkel JM, Asselin BL, Athale UH, Clavell LA, Michon B, Laverdiere C, Larsen E, Kelly KM, Silverman LB.. Impact of hemochromatosis gene mutations on cardiac status in doxorubicin-treated survivors of childhood high-risk leukemia. Cancer 2013;119:3555–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hildebrandt MAT, Reyes M, Wu X, Pu X, Thompson KA, Ma J, Landstrom AP, Morrison AC, Ater JL.. Hypertension susceptibility loci are associated with anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity in long-term childhood cancer survivors. Sci Rep 2017;7:9698.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El-Tokhy MA, Hussein NA, Bedewy AM, Barakat MR.. XPD gene polymorphisms and the effects of induction chemotherapy in cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients. Hematology 2014;19:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sajjad M, Fradley M, Sun W, Kim J, Zhao X, Pal T, Ismail-Khan R.. An exploratory study to determine whether BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers have higher risk of cardiac toxicity. Genes (Basel) 2017;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rajic V, Aplenc R, Debeljak M, Prestor VV, Karas-Kuzelicki N, Mlinaric-Rascan I, Jazbec J.. Influence of the polymorphism in candidate genes on late cardiac damage in patients treated due to acute leukemia in childhood. Leuk Lymphoma 2009;50:1693–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rossi D, Rasi S, Franceschetti S, Capello D, Castelli A, De Paoli L, Ramponi A, Chiappella A, Pogliani EM, Vitolo U, Kwee I, Bertoni F, Conconi A, Gaidano G.. Analysis of the host pharmacogenetic background for prediction of outcome and toxicity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP21. Leukemia 2009;23:1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Megías-Vericat JE, Montesinos P, Herrero MJ, Moscardó F, Bosó V, Rojas L, Martínez-Cuadrón D, Rodríguez-Veiga R, Sendra L, Cervera J, Poveda JL, Sanz MÁ, Aliño SF.. Impact of NADPH oxidase functional polymorphisms in acute myeloid leukemia induction chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J 2018;18:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Windsor RE, Strauss SJ, Kallis C, Wood NE, Whelan JS.. Germline genetic polymorphisms may influence chemotherapy response and disease outcome in osteosarcoma: a pilot study. Cancer 2012;118:1856–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wasielewski M, van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Westerink ND, Jongbloed JD, Postma A, Gietema JA, van Tintelen JP, van den Berg MP.. Potential genetic predisposition for anthracycline-associated cardiomyopathy in families with dilated cardiomyopathy. Open Heart 2014;1:e000116.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang X, Liu W, Sun CL, Armenian SH, Hakonarson H, Hageman L, Ding Y, Landier W, Blanco JG, Chen L, Quinones A, Ferguson D, Winick N, Ginsberg JP, Keller F, Neglia JP, Desai S, Sklar CA, Castellino SM, Cherrick I, Dreyer ZE, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Yasui Y, Relling MV, Bhatia S.. Hyaluronan synthase 3 variant and anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:647–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ruiz-Pinto S, Pita G, Martín M, Alonso-Gordoa T, Barnes DR, Alonso MR, Herraez B, García-Miguel P, Alonso J, Pérez-Martínez A, Cartón AJ, Gutiérrez-Larraya F, García-Sáenz JA, Benítez J, Easton DF, Patiño-García A, González-Neira A.. Exome array analysis identifies ETFB as a novel susceptibility gene for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;167:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ruiz-Pinto S, Pita G, Patiño-García A, Alonso J, Pérez-Martínez A, Cartón AJ, Gutiérrez-Larraya F, Alonso MR, Barnes DR, Dennis J, Michailidou K, Gómez-Santos C, Thompson DJ, Easton DF, Benítez J, González-Neira A.. Exome array analysis identifies GPR35 as a novel susceptibility gene for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2017;27:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aminkeng F, Bhavsar AP, Visscher H, Rassekh SR, Li Y, Lee JW, Brunham LR, Caron HN, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Amstutz U, Rieder MJ, Bernstein D, Carleton BC, Hayden MR, Ross CJ; Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety Consortium. A coding variant in RARG confers susceptibility to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47:1079–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang X, Sun CL, Quinones-Lombrana A, Singh P, Landier W, Hageman L, Mather M, Rotter JI, Taylor KD, Chen YD, Armenian SH, Winick N, Ginsberg JP, Neglia JP, Oeffinger KC, Castellino SM, Dreyer ZE, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Blanco JG, Bhatia S.. CELF4 variant and anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy: a Children's Oncology Group Genome-Wide Association Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schneider BP, Shen F, Gardner L, Radovich M, Li L, Miller KD, Jiang G, Lai D, O'Neill A, Sparano JA, Davidson NE, Cameron D, Gradus-Pizlo I, Mastouri RA, Suter TM, Foroud T, Sledge GW Jr. Genome-wide association study for anthracycline-induced congestive heart failure. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Todorova VK, Makhoul I, Dhakal I, Wei J, Stone A, Carter W, Owen A, Klimberg VS.. Polymorphic variations associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients. Oncol Res 2017;25:1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wells QS, Veatch OJ, Fessel JP, Joon AY, Levinson RT, Mosley JD, Held EP, Lindsay CS, Shaffer CM, Weeke PE, Glazer AM, Bersell KR, Van Driest SL, Karnes JH, Blair MA, Lagrone LW, Su YR, Bowton EA, Feng Z, Ky B, Lenihan DJ, Fisch MJ, Denny JC, Roden DM.. Genome-wide association and pathway analysis of left ventricular function after anthracycline exposure in adults. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2017;27:247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beauclair S, Formento P, Fischel JL, Lescaut W, Largillier R, Chamorey E, Hofman P, Ferrero JM, Pages G, Milano G.. Role of the HER2 [Ile655Val] genetic polymorphism in tumorogenesis and in the risk of trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1335–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gomez Pena C, Davila-Fajardo CL, Martinez-Gonzalez LJ, Carmona-Saez P, Soto Pino MJ, Sanchez Ramos J, Moreno Escobar E, Blancas I, Fernandez JJ, Fernandez D, Correa C, Cabeza Barrera J.. Influence of the HER2 Ile655Val polymorphism on trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity in HER2-positive breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2015;25:388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lemieux J, Diorio C, Cote MA, Provencher L, Barabe F, Jacob S, St-Pierre C, Demers E, Tremblay-Lemay R, Nadeau-Larochelle C, Michaud A, Laflamme C.. Alcohol and HER2 polymorphisms as risk factor for cardiotoxicity in breast cancer treated with trastuzumab. Anticancer Res 2013;33:2569–2576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Roca L, Dieras V, Roche H, Lappartient E, Kerbrat P, Cany L, Chieze S, Canon JL, Spielmann M, Penault-Llorca F, Martin AL, Mesleard C, Lemonnier J, de Cremoux P.. Correlation of HER2, FCGR2A, and FCGR3A gene polymorphisms with trastuzumab related cardiac toxicity and efficacy in a subgroup of patients from UNICANCER-PACS 04 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;139:789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stanton SE, Ward MM, Christos P, Sanford R, Lam C, Cobham MV, Donovan D, Scheff RJ, Cigler T, Moore A, Vahdat LT, Lane ME, Chuang E.. Pro1170 Ala polymorphism in HER2-neu is associated with risk of trastuzumab cardiotoxicity. BMC Cancer 2015;15:267.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boekhout AH, Gietema JA, Milojkovic Kerklaan B, van Werkhoven ED, Altena R, Honkoop A, Los M, Smit WM, Nieboer P, Smorenburg CH, Mandigers CM, van der Wouw AJ, Kessels L, van der Velden AW, Ottevanger PB, Smilde T, de Boer J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Kema IP, de Vries EG, Schellens JH.. Angiotensin II-receptor inhibition with candesartan to prevent trastuzumab-related cardiotoxic effects in patients with early breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1030–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Eldridge S, Guo L, Mussio J, Furniss M, Hamre J 3rd, Davis M.. Examining the protective role of ErbB2 modulation in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Sci 2014;141:547–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Udagawa C, Nakamura H, Ohnishi H, Tamura K, Shimoi T, Yoshida M, Yoshida T, Totoki Y, Shibata T, Zembutsu H.. Whole exome sequencing to identify genetic markers for trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. Cancer Sci 2018;109:446–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Serie DJ, Crook JE, Necela BM, Dockter TJ, Wang X, Asmann YW, Fairweather D, Bruno KA, Colon-Otero G, Perez EA, Thompson EA, Norton N.. Genome-wide association study of cardiotoxicity in the NCCTG N9831 (Alliance) adjuvant trastuzumab trial. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2017;27:378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular toxic effects of targeted cancer therapies. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1457–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Johnson DC, Corthals S, Ramos C, Hoering A, Cocks K, Dickens NJ, Haessler J, Goldschmidt H, Child JA, Bell SE, Jackson G, Baris D, Rajkumar SV, Davies FE, Durie BG, Crowley J, Sonneveld P, Van Ness B, Morgan GJ.. Genetic associations with thalidomide mediated venous thrombotic events in myeloma identified using targeted genotyping. Blood 2008;112:4924–4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bagratuni T, Kastritis E, Politou M, Roussou M, Kostouros E, Gavriatopoulou M, Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou E, Kanelias N, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA.. Clinical and genetic factors associated with venous thromboembolism in myeloma patients treated with lenalidomide-based regimens. Am J Hematol 2013;88:765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Di Stefano AL, Labussiere M, Lombardi G, Eoli M, Bianchessi D, Pasqualetti F, Farina P, Cuzzubbo S, Gallego-Perez-Larraya J, Boisselier B, Ducray F, Cheneau C, Moglia A, Finocchiaro G, Marie Y, Rahimian A, Hoang-Xuan K, Delattre JY, Mokhtari K, Sanson M.. VEGFA SNP rs2010963 is associated with vascular toxicity in recurrent glioblastomas and longer response to bevacizumab. J Neurooncol 2015;121:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.U.S. National Library of Medicine.DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/ (8 October 2018, date last accessed).

- 66. Magdy T, Schuldt AJT, Wu JC, Bernstein D, Burridge PW.. Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cells to assess drug cardiotoxicity: opportunities and problems. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2018;58:83–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Patsch C, Challet-Meylan L, Thoma EC, Urich E, Heckel T, O’Sullivan JF, Grainger SJ, Kapp FG, Sun L, Christensen K, Xia Y, Florido MHC, He W, Pan W, Prummer M, Warren CR, Jakob-Roetne R, Certa U, Jagasia R, Freskgård P-O, Adatto I, Kling D, Huang P, Zon LI, Chaikof EL, Gerszten RE, Graf M, Iacone R, Cowan CA.. Generation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2015;17:994–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]