Abstract

Ensuring identity, purity, and reproducibility are equally essential during synthetic chemistry, drug discovery, and for pharmaceutical product safety. Many peptidic APIs are large molecules that require considerable effort for integrity assurance. This study builds on quantum mechanical 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA) to establish NMR peptide sequencing methodology that overcomes the intrinsic limitations of principal compendial methods in identifying small structural changes or minor impurities that affect effectiveness and safety. HiFSA sequencing yields definitive identity and purity information concurrently, allowing for API quality assurance and control (QA/QC). Achieving full peptide analysis via NMR building blocks, the process lends itself to both research and commercial applications as 1D 1H NMR (HNMR) is the most sensitive and basic NMR experiment. The generated HiFSA profiles are independent of instrument or software tools and work at any magnetic field strength. Pairing with absolute or 100% qHNMR enables quantification of mixtures and/or determination of peptide conformer populations. Demonstration of the methodology uses single amino acids (AAs) and peptides of increasing size, including the octapeptide, angiotensin II, and the nonapeptide, oxytocin. The feasibility of HiFSA coupled with automated NMR and qHNMR for use in QC/QA efforts is established through case-based examples and recommended procedures.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Peptide-based pharmaceutical products have played a substantial role in medical practice since the 1920s. Currently, 60 USFDA approved peptide therapeutics are on the market.1–3 Just in 2017, of the 34 newly approved chemical entities, six were peptide therapeutics, and 12 were biologics.2 The number of peptide therapeutics introduced to the pharmaceutical market is expected to grow further as biological and biosimilar therapies as well as peptide specific formulations continue to improve. Connected to this proliferation are increasing challenges associated with peptide quality control (QC). Commonly, several analytical techniques are used in combination, such as MS, HPLC, and elemental or peptide content analysis, to verify identity and purity.4 As no individual method can fully address both identity and purity, more than one method is required. The goal of the present study was to show how 1D 1H NMR analysis can not only complement but also establish peptide purity and identity simultaneously and largely independently. Although representing the most basic NMR experiment, and despite the limitations of other established protocols, the extraordinary capabilities of 1D 1H NMR are rarely tapped for this purpose.

The present study builds on the long-known concept of Full Spin Analysis (FSA), a quantum mechanics driven method established early in the history of NMR, primarily for the interpretation of 1D 1H NMR spectra. The present development of a peptide analysis that only requires readily acquired 1D 1H NMR spectra utilizes an iterative FSA approach: the 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA) is a term that was coined in 2013 for a protocol that evolved from the FSA concepts introduced some 60 years ago. HiFSA provides a way to fully and accurately characterize all of the essential NMR spin parameters (δ, J, v [syn. ω1/2]) for any particular compound, even in the presence of strong overlap and higher order effects.5 This is especially important as structural complexity increases; each spin parameter still reflects structural characteristics of a compound and represents detailed structural knowledge that can lead to insights on both physicochemical (solubility, chemical interactions) and biological properties (target binding, content of active conformer).6 This applies particularly for peptides as biologically active compounds, where small structural changes can have a major impact on the expected pharmaceutical, biological, or physical properties.

As their size increases, peptides become increasingly difficult to fully characterize. The different levels of organization of peptides and proteins are summarized in their primary, secondary, tertiary, and sometimes quaternary structures.7 While their primary structure consists of the plain amino acid (AA) sequence, secondary structure relates to local organized structural conformations, mainly as α-helix, β-sheets, and many others defined in the Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure, originally a computer program called DSSP (define secondary structure of proteins).8 Tertiary structure refers to the global three-dimensional shape of the molecule. Rotational conformers visible on the NMR time scale affect the observed tertiary structure, especially for nonlinear peptides. The ratio of conformers can be determined by relative and absolute qNMR, including through HiFSA. If analyzed under physiological temperature and media, it is possible to determine the ratio of conformers with likely physiological relevance. This relates more closely to the overall biological activity of a peptide or protein of interest, as commonly, a single conformation can be responsible for the observed activity.9 Such information could then be used to further direct and develop structure activity relationship (SAR) studies.

The HiFSA sequencing approach treats peptides as sequences of AAs with negligible homonuclear spin coupling between them. The underlying hypotheses is that peptide 1H NMR spectra can be analyzed as emerging from isolated spin–spin coupled systems of the AAs, separated by amide linkages. An isolated 1H spin system refers to a series of coupled hydrogens that are isolated from other 1H spins by elements, such as heteroatoms or consecutive non-hydrogen containing carbons. Heteronuclear couplings including (e.g., 13C) isotopes are not considered in this study, as they have no impact on the proof of concept. In the case of AAs, the R group, also known as the AA side chain, of an individual AA has negligible to no coupling to the R group of a neighboring AA, especially in deuterated forms of protic solvents, such as D2O and CD3OD. However, in aprotic solvents, such as DMSO-d6, small couplings can be observed with the associated amide hydrogen but rarely to the neighboring AA.

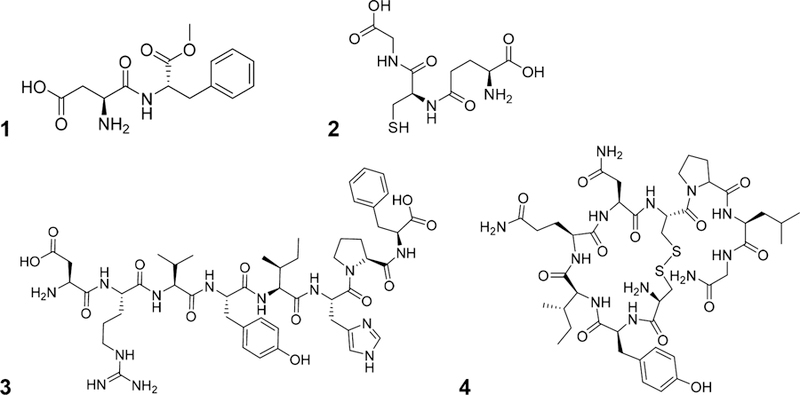

The concept of “assembling” HiFSA profiles through individual building blocks was first introduced by Napolitano et al. through its application to steviol glycosides.10 The method was applied subsequently to the tridecapeptide, ecumicin, a potential anti-TB lead compound, and its congeners, where small structural changes were analyzed through spectral subtraction and HiFSA AA analysis.11 Furthermore, the concept has recently been applied to the analysis of complex oligomeric proanthrocyanidins.12,13 The present report establishes universal HiFSA sequencing methodology for biologically active peptides. The method can be used for quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) in both drug discovery and industrial/manufacturing applications and can complement or even replace other widespread methods. Importantly, HiFSA and qNMR are presented as feasible methods that overcome the limitations commonly associated with NMR for QC efforts. In the present work, the HiFSA methodology was demonstrated using aspartame (1, case 1), glutathione (2, case 2), angiotensin II (3, case 3), oxytocin (4, case 4), and an extension of case 3, the stepwise synthesis of the oligopeptide 3. Two additional challenge cases were also designed to demonstrate the robust nature of the method.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Common AAs.

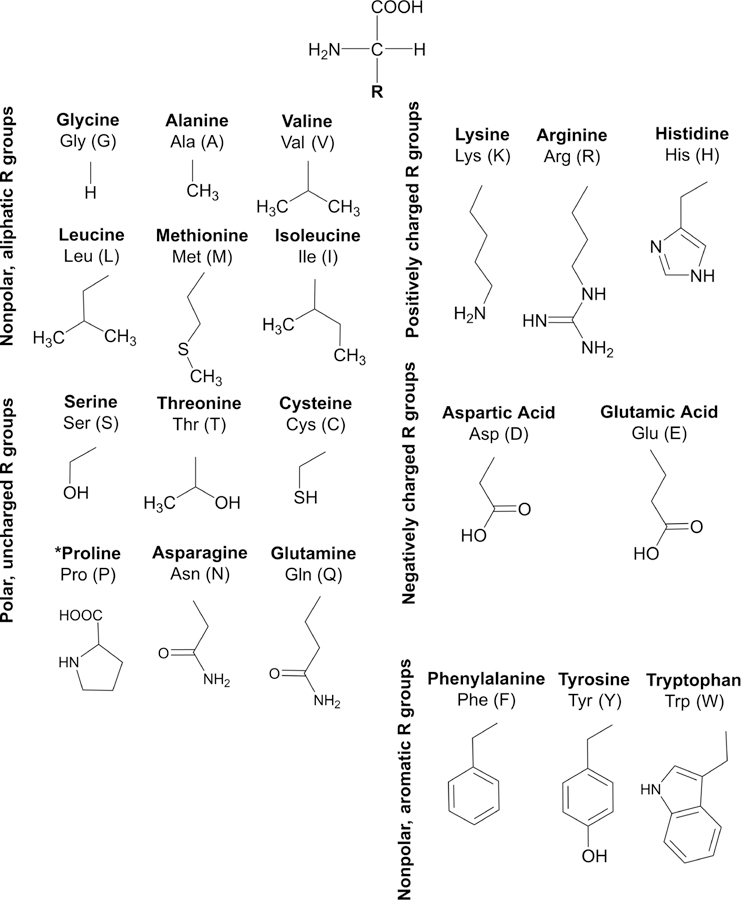

The HiFSA profiles for the 20 common AAs were generated using raw NMR experimental data retrieved from the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB).14–17 Specific details pertaining to each AA and the database reference number for retrieval can be found in Table 1. Labeling schemes were designed to match the labeling requirements of the worldwide Protein Data Bank (PDB) and are displayed for reference in Figure 1. Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 summarize the NMR parameters (δ in ppm, J in Hz) organized by AA class.

Table 1.

List of AAs and Their Raw 1H NMR Data Obtained from Databases

| AA (abbreviations) | formula | MW | database ref no. | NMR (MHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| glycine (Gly/G) | C2H5NO2 | 75.07 | HMDB0000123 | 500 |

| l-alanine (Ala/A) | C3H7NO2 | 89.09 | HMDB0000161 | 500 |

| l-arginine (Arg/R) | C6H14N4O2 | 174.20 | HMDB0000517 | 500 |

| l-asparagine (Asn/N) | C4H8N2O3 | 132.12 | HMDB0000168 | 500 |

| l-aspartic acid (Asp/D) | C4H7NO4 | 133.10 | HMDB0000191 | 600 |

| l-cysteine (Cys/C) | C3H7NO2S | 121.15 | HMDB0000574 | 500 |

| l-glutamic acid (Glu/E) | C5H9NO4 | 147.13 | HMDB0000148 | 500 |

| l-glutamine (Gln/Q) | C5H10N2O3 | 146.15 | HMDB0000641 | 500 |

| l-histidine (His/H) | C6H9N3O2 | 155.16 | HMDB0000177 | 600 |

| l-isoleucine (Ile/I) | C6H13NO2 | 131.18 | HMDB0000172 | 600 |

| l-leucine (Leu/L) | C6H13NO2 | 131.18 | HMDB0000687 | 500 |

| l-lysine (Lys/K) | C6H14N2O2 | 146.19 | BMSE00043 | 500 |

| l-methionine (Met/M) | C5H11NO2S | 149.21 | HMDB0000696 | 500 |

| l-phenylalanine (Phe/F) | C9H11NO2 | 165.19 | HMDB0000159 | 500 |

| l-proline (Pro/P) | C5H9NO2 | 115.13 | HMDB0000162 | 600 |

| l-serine (Ser/S) | C3N7NO3 | 105.09 | HMDB0000187 | 600 |

| l-threonine (Thr/T) | C4H9NO3 | 119.12 | HMDB0000167 | 500 |

| L-tryptophan (Trp/W) | C11H12N2O2 | 204.23 | HMDB0000929 | 600 |

| l-tyrosine (Tyr/Y) | C9H11NO3 | 181.19 | HMDB0000158 | 600 |

| l-valine (Val/V) | C5H11NO2 | 117.15 | HMDB0000883 | 500 |

Figure 1.

The 20 common AAs with their R groups, classified by chemical characteristics and with PDB labeling schemes.

Table 2.

Nonpolar, Aliphatic AAsa

| glycine (Gly/ G) | l-alanine (Ala/A) | l-valine (Val/V) | l-leucine (Leu/L) | l-methionine (Met/M) | l-isoleucine (Ile/I) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 3.550 (s, 2H) | α | 3.773 (q, 1H), 7.25 | α | 3.601 (d, 1H), 4.34 | α | 3.726 (dd, 1H), 8.89, 5.24 | α | 3.852 (dd, 1H), 5.26, 7.19 | α | 3.661 (d, 1H), 3.98 |

| β | 1.467 (d, 3H), 7.25 | β | 2.261 (dqq, 1H), 4.34, 7.04, 7.00 | β2 | 1.671 (ddd, 1H), 8.89, −13.9, 5.68 | β2 | 2.189 (dddd, 1H), 5.26, −14.78, 7.64, 8.28 | β | 1.968 (dddq, 1H), 3.98, 7.02, 4.78, 9.34 | ||

| γ1 | 1.029 (d, 3H), 7.04 | β3 | 1.730 (ddd, 1H), 5.24, −13.9, 8.08 | β3 | 2.112 (dddd, 1H), 7.19, −14.78, 6.55, 7.92 | γ12 | 1.456 (ddq, 1H), 4.78, −13.5, 7.57 | ||||

| γ2 | 0.9762 (d, 3H), 7.00 | γ | 1.699 (ddqq, 1H), 5.68, 8.08, 6.46, 6.59 | γ2 | 2.635 (ddd, 1H), 7.64, 6.55, −13.3 | γ13 | 1.248 (ddq, 1H), 9.34, −13.5, 7.29 | ||||

| δ1 | 0.9541 (d, 3H), 6.46 | γ3 | 2.628 (ddd, 1H), 8.28, 7.92, −13.3 | γ2 | 0.9969 (d, 3H), 7.02 | ||||||

| δ2 | 0.9427 (d, 3H), 6.59 | δ | δ1 | 0.9260 (dd, 11H),7.57,7.29 7.7.57, | |||||||

| ε | 2.125 (s, 3H) | ||||||||||

NMR parameters determined by HiFSA analysis: δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz].

Table 3.

Polar, Uncharged AAsa

| l-serine (Ser/S) | l-threonine (Thr/T) | l-cysteine (Cys/C) | l-proline (Pro/P) | l-asparagine (Asp/D) | l-glutamine (Gln/Q) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 3.833 (dd, 1H), 5.92, 3.52 | α | 3.576 (d, 1H), 4.89 | α | 3.970 (dd, 1H), 4.04, 5.78 | α | 4.118 (dd, 1H), 8.77, 6.60 | α | 4.00 (dd, 1H), 4.15, 7.81 | α | 3.766 (dd, 1H), 5.77, 6.58 |

| β2 | 3.939 (dd, 1H), 5.92, −12.3 | β | 4.244 (dq, 1H), 4.89, 6.59 | β2 | 3.026 (dd, 1H), 4.04, −14.9 | β2 | 2.336 (dddd, 1H), 8.77, −13.3, 6.68, 7.68 | β2 | 2.942 (dd, 1H), 4.15, −16.9 | β2 | 2.134 (dddd, 1H), 5.77, −14.6, 6.28, 9.40 |

| β3 | 3.976 (dd, 1H), 3.52, −12.3 | γ2 | 1.316 (d, 3H), 6.59 | β3 | 3.095 (dd, 1H), 5.78, −14.9 | β3 | 2.057 (dddd, 1H), 6.60, −13.3, 7.49, 6.78 | β3 | 2.847 (dd, 1H), 7.81, −16.9 | β3 | 2.117 (dddd, 1H), 6.58, −14.6, 9.42, 6.13 |

| γ2 | 1.979 (ddddd, 1H), 6.68, 7.49, −13.2, 6.91, 7.53 | γ2 | 2.456 (ddd, 1H), 6.28, 9.42, −15.4 | ||||||||

| γ3 | 2.008 (ddddd, 1H), 7.68, 6.78, −13.2, 7.52, 6.68 | γ3 | 2.429 (ddd, 1H), 9.40, 6.13, −15.4 | ||||||||

| δ2 | 3.325 (ddd, 1H), 6.91, 7.52, −11.6 | ||||||||||

| δ3 | 3.409 (ddd, 1H), 7.53, 6.68, −11.6 | ||||||||||

NMR parameters determined by HiFSA analysis: δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz].

Table 4.

Positively Charged AAsa

| l-lysine (Lys/K) | l-arginine (Arg/R) | l-histidine (His/H) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 3.746 (dd, 1H), 5.63, 6.53 | α | 3.756 (dd, 1H), 5.99, 6.33 | Α | 3.983 (dd, 1H), 4.91, 7.78 |

| β2 | 1.907 (dddd, 1H), 5.63, −14.5, 11.36, 5.13 | β2 | 1.901 (dddd, 1H), 5.99, −14.3, 11.4, 4.87 | β2 | 3.244 (ddd, 1H), 4.91, −15.6, 0.915 |

| β3 | 1.884 (dddd, 1H), 6.53, −14.5, 5.13, 11.4 | β3 | 1.888 (dddd, 1H), 6.33, −14.3, 5.12, 11.6 | β3 | 3.153 (ddd, 1H), 7.78, −15.6, 0.678 |

| γ2 | 1.499 (ddddd, 1H), 5.13, 11.4, −13.3, 5.45, 10.1 | γ2 | 1.637 (ddddd, 1H), 11.4, 5.12, −13.6, 6.94, 6.99 | γ | |

| γ3 | 1.432 (ddddd, 1H), 11.4, 5.13, −13.3, 9.87, 5.57 | γ3 | 1.711 (ddddd, 1H), 4.87, 11.6, −13.6, 6.97, 6.94 | δ1 | |

| δ2 | 1.721 (ddddd, 1H), 9.87, 5.45, −15.6, 6.92, 7.88 | δ2 | 3.234 (ddd, 1H), 6.94, 6.97, −13.6 | δ2 | 7.905 (ddd, 1H), 0.915, 0.678, 1.26 |

| δ3 | 1.712 (ddddd, 1H), 5.57, 10.1, −15.6, 10.0, 5.45 | δ3 | 3.23 (ddd, 1H), 6.99, 6.94, −13.6 | ε1 | 7.094 (d, 1H), 1.26 |

| ε2 | 3.014 (ddd, 1H), 6.92, 10.0, −14.8 | ||||

| ε3 | 3.010 (ddd, 1H), 7.88, 5.45, −14.8 | ||||

NMR parameters determined by HiFSA analysis: δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz].

Table 5.

Negatively Charged AAsa

| l-aspartic acid (Asp/D) | l-glutamic acid (Glu/E) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| α | 3.891 (dd, 1H), 3.66, 8.87 | α | 3.748 (dd, 1H), 7.30, 4.64 |

| β2 | 2.801 (dd, 1H), 3.66, −17.5 | β2 | 2.043 (dddd, 1H), 7.30, −14.8, 6.35, 8.66 |

| β3 | 2.664 (dd, 1H), 8.87, −17.5 | β3 | 2.117 (dddd, 1H), 4.64, −14.8, 8.71, 6.78 |

| γ2 | 2.331 (ddd, 1H), 6.35, 8.71, −16.0 | ||

| γ3 | 2.349 (ddd, 1H), 8.66, 6.78, −16.0 | ||

NMR parameters determined by HiFSA analysis: δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz].

Table 6.

Nonpolar, Aromatic AAsa

| l-phenylalanine (Phe/F) | l-tyrosine (Tyr/Y) | l-tryptophan (Trp/W) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 3.982 (dd, 1H), 5.21, 7.91 | α | 3.931 (dd, 1H), 5.15, 7.77 | α | 4.046 (dd, 1H), 4.83, 8.09 |

| β2 | 3.271 (ddd, 1H), 5.21, −14.5, 0.573 | β2 | 3.185 (ddd, 1H), 5.15, −14.7, 0.499 | β2 | 3.472 (dd, 1H), 4.83, −15.4 |

| β3 | 3.112 (ddd, 1H), 7.91, −14.5, 0.450 | β3 | 3.044 (ddd, 1H), 7.77, −14.7, 0.426 | β3 | 3.293 (dd, 1H), 8.09, −15.4 |

| δ | 7.317 (dddddd, 2H), 0.573, 0.450, 1.97, 7.71, 0.529, 1.20 | δ | 7.181 (ddddd, 2H), 0.499, 0.426, 2.59, 8.43, 0.442 | δ1 | 7.309 (s, 1H) |

| ε | 7.416 (dddd, 2H), 7.71, 0.529, 1.30, 7.48 | ε | 6.889 (ddd, 2H), 8.34, 0.442, 2.59 | ε3 | 7.723 (ddd, 1H), 0.271, 1.06, 8.00 |

| ζ | 7.366 (dd, 1H), 1.20, 7.48 | ζ2 | 7.531 (ddd, 1H), 8.21, 0.926, 0.271 | ||

| η2 | 7.191 (ddd, 1H), 0.926, 7.05, 8.00 | ||||

| ζ3 | 7.274 (ddd, 1H), 8.21, 7.05, 1.06 | ||||

NMR parameters determined by HiFSA analysis: δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz].

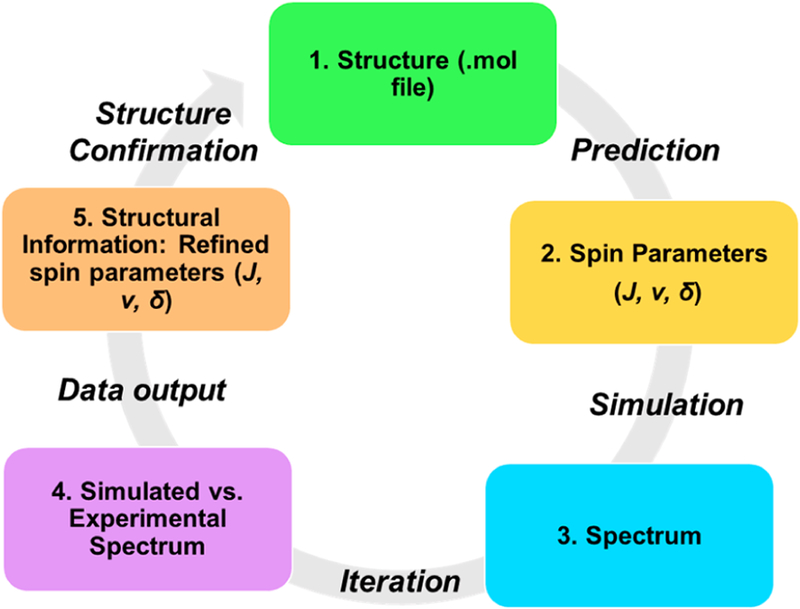

Generation of the individual AA HiFSA profiles followed the general procedure depicted in Figure 2. First, a MOL structure file was created, which was imported into the PERCH Molecular Modeling Software (MMS) and converted to a 3D MMS file. Geometric optimization (GO) was applied to all structures to obtain the lowest energy conformation. Conformational analysis was used only for the prediction of spin parameters of single AAs. Structures were then labeled according to PDB nomenclature, and the NMR solvent used in the experimentally acquired spectra was specified (D2O for all single AAs). The NMR parameters were then predicted with chemical shift referenced to 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS, 0.0 ppm).

Figure 2.

General workflow of the HiFSA parameter generation.

Experimental spectra were imported into the software as processed JDX files. Peak picking and integration were performed within the software through the PAC module. The predicted NMR parameters were used to quantum mechanically calculate a theoretical spectrum for further comparison and optimization with respect to the experimental spectrum. Chemical shifts (δ) were preassigned manually for each spin particle prior to iteration to minimize the initial difference between QM-calculated and experimental spectra. The iteration process was performed until the agreement between QM-calculated and experimental spectra reached convergence with a total intensity root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) below 0.1%, normalized to the largest intensity in the spectrum. The resulting NMR parameters were then exported as a text file and used to generate the resulting QM-calculated spectra using the PERCH simulation module.

At this point, one important aspect of HiFSA-related nomenclature should be mentioned regarding the use of the terms calculation vs simulation. Provided that all relevant spin parameters are known, QM theory describes NMR spin systems fully and unambiguously. Moreover, it is important to realize that QM-based calculations yield NMR spectra that can serve as true reference points for experimental spectra, which are inherently limited by imperfections due to residual magnetic inhomogeneity (shimming), signal processing, and sample related (impurity) artifacts. While the term simulation implies that a process seeks to approximate a system for which no exact mathematical treatment is known, QM-based calculations of NMR spectra do employ known exact equations and, therefore, should at least be considered exact simulations. Accordingly, the present study uses the term “QM-calculation” for all spectra that were calculated from their HiFSA profiles. In this context, the term “iteration” refers to the repetition of simulations after adjustment of the NMR spin parameters. This process is typically repeated until the calculated and the observed spectrum match and can be performed manually and/or with the help of a software tool (iterator; see Table S7 for a list of software tools).

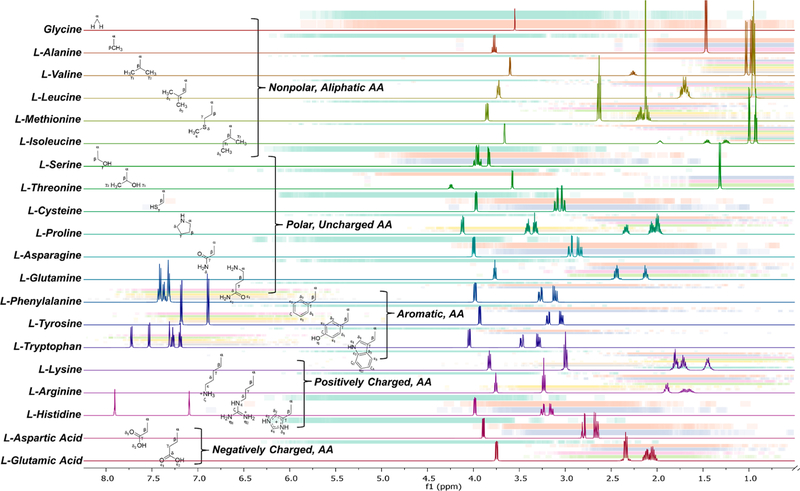

Figure 3 shows a summary of the HiFSA-generated and QM-calculated spectra of each individual AA. In addition, a supplementary analysis was performed using the 200 largest proteins deposited in the BMRB (as of July 7, 2017) to map the environmental effects that 2° and 3° peptide and protein structure can have on individual hydrogen signals. The distribution of each hydrogen signal is represented as individual bars for every AA. The drastic change in chemical shift (Δδ) that a single hydrogen signal can experience can be attributed to environmental effects of neighboring AAs, in particular, aromatic AAs, such as Tyr, Phe, and Trp. 9,18–20 These AAs can have pronounced anisotropic (de)shielding on the nearby hydrogens. For this reason, the HiFSA starting profile of a single AA requires iterative optimization, particularly of the δ values, when being combined into the HiFSA profile of its corresponding peptide.

Figure 3.

HiFSA-generated 1H NMR profiles of common AAs at experimentally collected frequencies with the distributions of each 1H chemical shift generated from the top-200 largest proteins of the BMRB database (accessed on July 7, 2017). Each 1H nucleus of each AA is represented by one colored line, in the order of the NMRSTAR format. The color intensity reflects the density of the distribution.

As a single, symmetric, and nonchiral AA, Gly gives a singlet with an integral of 2H. However, as will be seen in the cases below, the two Hα of Gly show two doublets with a large geminal coupling constant of ~16 Hz, reflecting the chiral anisotropic environment of a peptide. Additionally, the Hβ for Thr follows a nontypical chemical shift pattern, where the Hβ resonates further downfield (4.24 ppm) than the Hα (3.58 ppm). Not represented in the table but observable in the spectrum for His were three conformers (71, 17, and 12%). Trp also has two observable conformers (58 and 42%). The major conformers of these two AAs are reported in Tables 4 and 6, respectively, while the minor conformers can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S1, Figure S1, Table S2, and Figure S2).

Methodology for Producing HiFSA Profiles of Peptides.

The HiFSA profiles for the common AAs served as a collection of 1H NMR “building blocks” that can be assembled into peptide spectra. Four important bioactive and pharmaceutical peptides of various lengths were selected as proof of concept cases (Figure 4), case 1, the dipeptide aspartame (1); case 2, the tripeptide glutathione (2); case 3, the octapeptide angiotensin II (3); and case 4, the nonapeptide oxytocin (4). In addition, several peptides were custom synthesized to progressively build compound 3, covering the range from the dipeptide to the full octapeptide in the extension of case 3.

Figure 4.

Structure of aspartame (1), glutathione (2), angiotensin II (3), and oxytocin (4).

Chemical shift assignments were made using either database reference information (HMBD or PDB) or via acquired 1H–1H COSY data. For each peptide, an initial definition of its spin systems was produced by manually combining the HiFSA profiles from the parameters of its individual AAs. The chemical shifts were adjusted manually according to molecular assignments and then optimized using the PERCHit Iterator, having the J values fixed to optimize δ first. The. J, δ, and line width (v [syn. ω1/2]) values were then optimized repetitively until the agreement between QM-calculated and experimental spectra reached convergence with a total RMSD < 0.1%.

Case 1: Aspartame.

Compound 1 (l-aspartyl-l-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester, Figure 4) is an artificial sweetener commonly used in food and beverages that is roughly 200 times sweeter than sucrose. Compound 1 was selected due to its structural flexibility, which is the property that makes identifying the conformation associated with its “sweet taste” difficult.21 There appears to be a consensus that 1 has two favored conformers, the “flat” extended conformer and the “L”-shaped trans conformer. While the former has been primarily associated with the sweet taste, 22 this designation involves a degree of ambiguity.

The initial spin system definition was created as described above, with the addition of a singlet methyl group for the modified Phe methyl ester. The experimental spectrum was retrieved from HMDB (ref# HMDB0001894). According to database records, the sample was prepared at a concentration of 44 mM with DSS as the internal reference in D2O at pH 7.0, and the spectrum was acquired at 298 K at 500 MHz using the HMBD standard experiment 1D-NOESY with presaturation for water suppression. Consistent with the literature, two conformers were observed in a ratio of 73:27 (Table 7 and Figure S3). On the basis of the ratio and the spectral parameters, the major conformer represented the “flat” conformation, whereas the minor conformer represented the “L” or trans conformer (Figure S4). This assignment was confirmed by the Δδ of Hβ3, resonating at 2.63 ppm in the major and 0.672 ppm in the minor conformer. This large, nearly 2.0 ppm difference, is an exemplary demonstration of aromatic shielding effects; only in the trans conformation, the aromatic ring in Phe bends outward from the main molecular plane such that the aromatic shielding cone lines up with the Hβ3 of Asp, with some fringe effects on Hβ2.

Table 7.

Aspartame (1) NMR Parameters Generated by HiFSA Analysis

|

δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals, J [Hz]) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| conformer 1 (73%) | conformer 2 (27%) | ||

| l-Asp | α | 4.137 (dd, 1H, 5.08, 8.20) | 4.093 (dd, 1H, 3.12, 10.7) |

| β2 | 2.735 (dd, 1H, 5.08, −17.3) | 2.159 (dd, 1H, 3.12, −16.8) | |

| β3 | 2.634 (dd, 1H, 8.20, −17.3) | 0.6720 (dd, 10.7, −16.8) | |

| O-Me-l-Phe | α | 4.793 (dd, 1H, 5.75, 8.92) | 4.786 (dd, 3.98, 4.79) |

| β2 | 3.241 (dd, 1H, 5.75, −14.0) | 3.266 (dd, 3.12, −14.0) | |

| β3 | 3.067 (dd, 1H, 8.92, −14.0) | 3.028 (dd, 4.79, −14.0) | |

| δ | 7.278 (dddd, 2H, 1.85, 7.70, 0.478, 1.16) | 7.202 (dddd, 2H, 1.92, 7.74, 0.487, 1.17) | |

| ε | 7.388 (dddd, 2H, 7.70, 0.478, 1.22, 7.48) | 7.408 (dddd, 2H, 7.74, 0.487, 1.50, 7.32) | |

| ζ | 7.331 (dd, 1H, 1.16, 7.48) | 7.382 (dd, 1H, 1.17, 7.32) | |

| OMe | 3.730 (s, 3H) | 3.350 (s, 3H) | |

Case 2: Glutathione.

The tripeptide 2 (l-γ-glutamyl-l-cysteinyl-glycine, Figure 4) contains l-glutamic acid, l-cysteine, and glycine and exhibits a unique γ peptide linkage between the terminal carboxyl group of the glutamic acid side chain and the amine group of cysteine. Compound 2 is an essential antioxidant and detoxifying agent that is responsible for neutralizing reactive radicals and peroxides in living organisms and a major cofactor in phase II xenobiotic metabolism. Compound 2 was also selected due to its unique peptide linkage and rich conformational dynamics. As was the case with 1, 2 conformational populations have been studied as they relate to its bioactivity. Raman spectroscopy showed three distinct conformations (β, PII, and αR, at 0.5 M in H2O, pH 7).23,24 The populations of the three major conformers was determined to be 60, 25, and 15%, respectively. Through a combination of several studies, it was determined that the structure of 2 is highly sensitive to its surrounding environment (pH, concentration, temperature, and solvent).23,24

Experimental 800 MHz 1H NMR data for 2 were acquired at 298 K using a 100 mM sample prepared in 600 μL of D2O with 50 mM sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4·H2O) (Table 8 and Figure S5). In contrast to reports, no conformers were observed.23,24 This may be due to concentration, salinity, or pH effects, or due to the fact, that the conformations cannot be observed on the NMR time scale. Also of note, Gly in 2 does not give rise to a singlet but a doublet consistent with a geminal J coupling of −17.8 Hz. This is due to anisotropic environmental effects of the surrounding AAs, which ultimately results from their individual chirality (chiral anisotropy).

Table 8.

Glutathione (2) NMR Parameters Generated by HiFSA Analysis

| δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals, J [Hz]) | ||

|---|---|---|

| γ-l-Glu | α | 3.834 (dd, 1H, 6.27, 6.50) |

| β2 | 2.180 (dddd, 1H, 6.27, −14.4, 8.56, 6.95) | |

| β3 | 2.172 (dddd, 1H, 6.50, −14.4, 6.45, 8.53) | |

| γ2 | 2.576 (ddd, 1H, 8.56, 6.45, −15.6) | |

| γ3 | 2.545 (ddd, 1H, 6.95, 8.53, −15.6) | |

| l-Cys | α | 4.571 (dd, 1H, 5.06, 7.17) |

| β2 | 2.963 (dd, 1H, 5.06, −14.2) | |

| β3 | 2.936 (dd, 1H, 7.17, −14.2) | |

| Gly | α2 | 3.985 (d, 1H, −17.8) |

| α3 | 3.970 (d, 1H, −17.8) | |

Case 3: Angiotensin II (3).

To illustrate the feasibility of HiFSA sequencing for larger peptides, the octapeptide compound 3 (l-Asp-l-Arg-l-Val-l-Tyr-l-Ile-l-His-l-Pro-l-Phe, Figure 4) was selected. Compound 3 is a peptide hormone with strong vasoconstrictive activity and has a prominent physiological role as a blood pressure elevating regulator; in humans, 3 increases the production of vasopressin in the CNS, causes constriction of the veins and arteries in the smooth muscles, and increases aldosterone secretion.25 The conformational population of 3 in water was previously studied by Zhou et al.,26 who identified two conformers with populations that were considerably affected by pH and were associated with the cis–trans isomerization of the His–Pro peptide bond. The minor cis conformer was found to be around 5% at pH 5.5 vs 12–20% at pH 7.

Compound 3 was obtained as an acetate and prepared in D2O:CD3OD (3:2) at a concentration of 9.5 mM in a 5 mm NMR tube. Spectra were referenced to residual CHD2OD (3.310 ppm). Assignments were first confirmed by 1H–1H COSY and 1H–13C HMBC spectra and then optimized by HiFSA sequencing (Table 9 and Figures S6–S9). While both conformers were observed, the minor cis conformer was difficult to fully characterize due to its low abundance (SNR 7 for most signals), signal overlap, and close similarity with the major conformer. Its abundance was determined to be ~5.5% through integration of its isolated signal at 4.19 ppm. Full characterization of the minor isomer was not pursued, but could be assisted by increasing the pH of the sample, sample concentration, and/or the number of transients acquired. However, this work still constitutes the first full 1H NMR characterization of 3, including all coupling constants of the major conformer.

Table 9.

Angiotensin II (3) 1H NMR Parameters Generated by HiFSA Analysis

| δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals, J [Hz]) | ||

|---|---|---|

| l-Asp | α | 4.245 (dd, 1H, 5.41, 8.10) |

| β2 | 2.819 (dd, 1H, 5.41, −17.2) | |

| β3 | 2.677 (dd, 1H, 8.10, −17.2) | |

| l-Arg | α | 4.346 (dd, 1H, 6.07, 8.07) |

| β2 | 1.743 (dddd, 1H, 6.07, −13.6, 10.7, 5.34) | |

| β3 | 1.712 (dddd, 1H, 8.07, −13.6, 4.90, 11.0) | |

| γ2 | 1.551 (ddddd, 1H, 10.7, 4.90, −13.8, 6.88, 7.20) | |

| γ3 | 1.520 (ddddd, 1H, 5.34, 11.0, −13.8, 7.19, 6.81) | |

| δ2 | 3.149 (ddd, 1H, 6.88, 7.19, −13.9) | |

| δ3 | 3.146 (ddd, 1H, 7.20, 6.81, −13.9) | |

| l-Val | α | 4.096 (d, 1H, 2.84) |

| β | 1.947 (dqq, 1H, 2.84, 6.73, 6.76) | |

| γ1 | 0.8950 (d, 3H, 6.73) | |

| γ2 | 0.8437 (d, 3H, 6.76) | |

| l-Tyr | α | 4.606 (dd, 1H, 6.61, 8.34) |

| β2 | 2.956 (dd, 1H, 6.61, −13.9) | |

| β3 | 2.853 (dd, 1H, 8.34, −13.9) | |

| δ | 7.075 (ddd, 1H, 2.72, 8.42, 0.229) | |

| ε | 6.725 (ddd, 1H, 8.42, 0.229, 2.77) | |

| l-Ile | α | 4.086 (d, 1H, 3.16) |

| β | 1.730 (dddq, 1H, 3.16, 6.83, 3.49, 8.99) | |

| γ12 | 1.363 (ddq, 1H, 3.49, −13.6, 7.50) | |

| γ13 | 1.098 (ddq, 1H, 8.99, −13.6, 7.50) | |

| γ2 | 0.8006 (d, 3H, 6.83) | |

| δ1 | 0.8121 (dd, 3H, 7.50, 7.50) | |

| l-His | α | 4.846 (dd, 1H, 5.96, 7.38) |

| β2 | 3.150 (ddd, 1H, 5.96, −15.6, 0.648) | |

| β3 | 3.065 (ddd, 1H, 7.38, −15.6, 0.656) | |

| δ2 | 7.225 (ddd, 1H, 0.648, 0.656, 1.40) | |

| ε1 | 8.546 (d, 1H, 1.40) | |

| l-Pro | ὰ | 4.386 (dd, 1H, 8.54, 4.65) |

| β2 | 2.180 (dddd, 1H, 8.54, −12.9, 6.65, 8.61) | |

| β3 | 1.904 (dddd, 1H, 4.65, −12.9, 5.18, 6.63) | |

| γ2 | 1.963 (ddddd, 1H, 6.65, 5.18, −12.2, 7.11, 6.02) | |

| γ3 | 1.893 (ddddd, 1H, 8.61, 6.63, −12.2, 7.07, 7.23) | |

| δ2 | 3.722 (ddd, 1H, 7.11, 7.07, −10.1) | |

| δ3 | 3.539 (ddd, 1H, 6.02, 7.23, −10.1) | |

| l-Phe | α | 4.427 (dd, 1H, 5.37, 6.89) |

| β2 | 3.154 (dd, 1H, 5.37, −13.9) | |

| β3 | 3.024 (dd, 1H, 6.89, −13.9) | |

| δ | 7.237 (dddd, 1H, 1.93, 7.60, 0.55, 1.20) | |

| ε | 7.293 (dddd, 1H, 7.60, 0.55, 1.38, 7.46) | |

| ζ | 7.221 (dd, 1H, 1.20, 7.46) | |

An analysis of the J values of 3 compared to those in the individual AAs was performed to determine the consistency of the AA profile. Notably, the average difference in coupling constants (ΔJ) expressed as absolute values was only 0.53 ± 0.56 Hz (mean ± standard deviation). For most AAs, the largest difference in J was observed in the Hα, except for Pro, where all J values were affected. The larger ΔJ observed for Hα hydrogens can be explained by the formation of the N–C backbone and the effect this has on the dihedral angle between Hα and Hβ2/3 when compared to individual amino acids. This translates to the ΔJ observed for Pro, as Pro is an in-chain-cyclized AA, and all dihedral angles observed for Pro are affected by the N–C backbone strain. Ignoring the Hα and Pro hydrogens, all other J values in 3 remained relatively constant, with ΔJ values of 0.26 ± 0.27 Hz. This also allowed for the conclusion that the J values of individual AA HiFSA profiles are highly suitable as start parameters when building HiFSA profiles of larger peptides.

Case 4: Oxytocin (4).

This nonapeptide 4 (l-Cys-l-Tyr-l-Ile-l-Gln-l-Asn-l-Cys-l-Pro-l-Leu-l-Gly, Figure 4) contains only common AAs. It was selected for its cyclic structure and relevance to human health. The structure contains a disulfide bond connecting two Cys residues, a structural moiety that occurs commonly in proteins. Compound 4 is a neuropeptide hormone produced in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and released during sexual reproduction, social bonding, and child birth, and subsequently, it stimulates lactation during breast feeding. While oxytocin has been extensively investigated by NMR to study its structural changes occurring with pH or solvent changes,27–29 its 1H NMR spectrum is still not understood fully.

For spectral acquisition, 4 (USP RS) was dissolved in DMSO-d6/CD3OD (4:1) at a concentration of 10 mM in a 5 mm NMR tube. The spectra were referenced to the residual solvent, DMSO-d5, at 2.500 ppm. Hydrogen resonance assignments were aided by 1H–1H-COSY and 1H–13C HMBC spectra and subsequently optimized by HiFSA (Table 10 and Figures S10–S13). In preparation of generating the HiFSA profile, the full NMR conformational analysis of oxytocin in H2O/D2O, as deposited in PDB (ref # 2MGO), was used.30 The PDB file was imported into the MMS 3D structure editor, and the prediction of the spin parameters was performed without the molecular modeling steps. A minor conformer observed had to remain unassigned due to its <0.5% abundance, as determined by the signal at 7.03 ppm. Collectively, this outcome constitutes the first full 1H NMR characterization of the major conformer of 4.

Table 10.

Oxytocin 1H NMR Parameters Generated by HiFSA Analysis

| δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals, J [Hz]) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Cys | α | 3.510 (dd, 1H, 7.13, 6.95) | l-Cys | α | 4.770 (dd, 1H, 7.02, 6.59) |

| β2 | 2.921 (dd, 1H, 7.13, −13.3) | β2 | 3.189 (dd, 1H, 7.02, −13.4) | ||

| β3 | 2.662 (dd, 1H, 6.95, −13.3) | β3 | 2.942 (dd, 1H, 6.59, −13.4) | ||

| l-Tyr | α | 4.598 (dd, 1H, 4.38, 10.9) | l-Pro | α | 4.304 (dd, 1H, 8.75, 3.70) |

| β2 | 3.154 (dd, 1H, 4.38, −14.3) | β2 | 2.025 (dddd, 1H, 8.75, −12.5, 10.4, 5.33) | ||

| β3 | 2.730 (ddd, 1H, 4.38, −14.3, 0.635) | β3 | 1.855 (dddd, 1H, 3.70, −12.5, 6.87, 6.90) | ||

| δ | 7.100 (dddd, 1H, 0.635, 2.57, 8.37,0.216) | γ2 | 1.890 (ddddd, 1H, 10.4, 6.87, −13.4, 8.25, 3.43) | ||

| ε | 6.660 (ddd, 1H, 8.37, 0.216, 2.57) | γ3 | 1.854 (ddddd, 1H, 5.33, 6.90, −13.4, 7.19, 8.29) | ||

| l-Ile | α | 3.890 (dd, 1H, 7.61, 4.06) | δ2 | 3.619 (ddd, 1H, 8.25, 7.19, −10.1) | |

| β | 1.806 (dddq, 1H, 7.61, 4.06, 9.14, 6.77) | δ3 | 3.492 (ddd, 1H, 3.43, 8.29, −10.1) | ||

| γ12 | 1.484 (ddq, 1H, 4.06, −13.5, 7.29) | l-Leu | α | 4.167 (dd, 1H, 9.97, 5.19) | |

| γ13 | 1.149 (ddq, 1H, 9.14, −13.5, 7.33) | β2 | 1.519 (ddd, 1H, 9.97, −13.9, 5.56) | ||

| γ2 | 0.8877 (d, 3H, 6.77) | β3 | 1.501 (ddd, 1H, 5.19, −13.9, 8.89) | ||

| δ1 | 0.8695 (dd, 3H, 7.29, 7.33) | γ | 1.617 (ddqq, 1H, 5.56, 8.89, 6.69, 6.56) | ||

| l-Gln | α | 3.992 (dd, 1H, 8.93, 4.64) | δ1 | 0.8814 (d, 3H, 6.69) | |

| β2 | 1.990 (dddd, 1H, 8.93, −13.7, 5.69, 8.83) | δ2 | 0.8235 (d, 3H, 6.65) | ||

| β3 | 1.883 (dddd, 1H, 4.64, −13.7, 9.28, 6.00) | l-Gly | α2 | 3.666 (d, 1H, −16.8) | |

| γ2 | 2.143 (ddd, 1H, 5.69, 9.28, −15.5) | α3 | 3.542 (d, 1H, −16.8) | ||

| γ3 | 2.142 (ddd, 1H, 8.83, 6.00, −15.5) | ||||

| l-Asn | α | 4.450 (dd, 1H, 7.32, 6.38) | |||

| β2 | 2.582 (dd, 1H, 7.32, −15.7) | ||||

| β3 | 2.585 (dd, 1H, 6.38, −15.7) | ||||

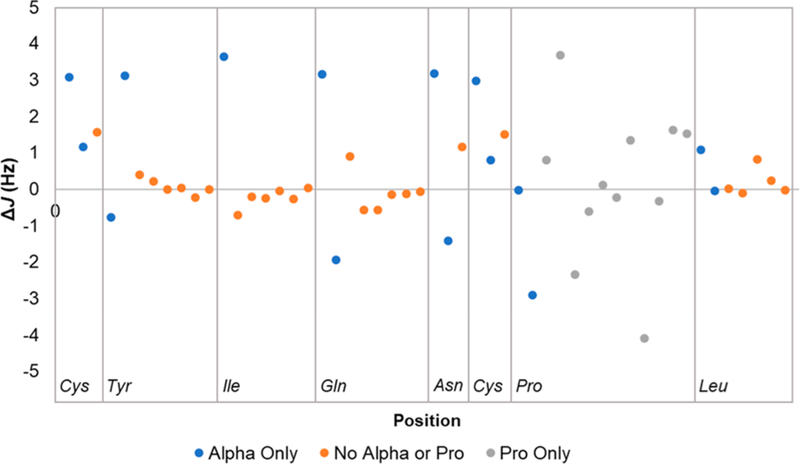

An analysis of the coupling constants was also performed on 4, to compare with that of the linear structure peptide, 3. In 4, the average ΔJ was still small but also higher (~2-fold) and clearly more variable at 1.38 ± 2.46 Hz, compared with 3. This result is expected, as the N–C backbone of a cyclic peptide experiences much greater strain and increased rigidity than most linear peptides. Interestingly, when Gly is removed from the calculation, the average ΔJ decreases to 1.04 ± 1.16 Hz (Figure 5). This indicates that Gly behaves structurally different than other AAs when comparing its single AA profile versus that within a peptide or protein. As mentioned earlier, Hα-Gly as a single AA appears as a singlet; however, due to the chiral anisotropy of the surrounding chemical environment of the peptide, the geminal Hα of Gly in 4 appears as two doublets consistent with a large geminal coupling of −16.8 Hz. When the ΔJ for only the Hα of each AA was considered, the average ΔJ increased to 2.88 ± 3.90 Hz (1.87 ± 1.26 Hz 406 without Gly), indicating the prominent involvement of the α position in AAs in the overall conformational arrangement of a cyclic peptide. The ΔJ for Pro alone was 1.51 ± 1.37 Hz. Without the Hα and Pro J values, the ΔJ dropped to 0.39 ± 0.46 Hz. This again was consistent with the observations made for 3, where the Hα and Pro J values experience by far the greatest degree of deviation from their single AA form, secondary to N–C backbone strain. This interdependence was observed to a greater degree with oxytocin because of its cyclic structure.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of the ΔJ values (Hz, oxytocin J – common AA J) of all oxytocin hydrogens versus their position within oxytocin. Gly is not included since it is a statistical outlier.

Extension of Case 3: Stepwise Building and HiFSA Sequencing of Angiotensin II.

To further underpin the feasibility of peptide HiFSA sequencing through individual AA profiling, 3 was “built” by both peptide synthesis from scratch and concomitant NMR, using peptides of increasing size. Starting with the single AA aspartic acid, each subsequent peptide was designed to represent the next AA addition within the sequence of 3. To ensure consistency between samples, individual AAs and the peptide were prepared at approximately the same molar concentration of 25–26 mM in 135 μL of D2O and 40 μL of CD3OD in 3 mm NMR tubes. The same acquisition parameters were applied, and δ referencing used the residual HDO signal (4.790 ppm). Assignments were confirmed using 1H,1H COSY spectra and then optimized by HiFSA (Table 11 and Figures S14–S28).

Table 11.

Building Angiotensin II One AA at a Timea

| D | DR | DRV | DRVY | DRVYI | DRVYIH | DRVYIHP | DRVYIHPF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Asp | α | 3.966 (dd, 1H), 4.09, 7.60 | 4.329 (dd, 1H), 4.76, 8.01 | 4.301 (dd, 1H), 5.00, 7.90 | 4.290 (dd, 1H), 4.90, 8.01 | 4.282 (dd, 1H), 4.99, 7.95 | 4.290 (dd, 1H), 5.04, 7.89 | 4.291 (dd, 1H), 5.03, 7.90 | 4.209 (dd, 1H), 8.12, 5.33 |

| β2 | 2.946 (dd, 1H), 4.09, −17.9 | 3.024 (dd, 1H), 4.76, −17.9 | 2.998 (dd, 1H), 5.00, −17.9 | 2.986 (dd, 1H), 4.90, −17.9 | 2.969 (dd, 1H), 4.99, −17.8 | 2.969 (dd, 1H), 5.04, −17.8 | 2.968 (dd, 1H), 5.03, −17.8 | 2.778 (dd, 1H), 8.12, −17.2 | |

| β3 | 2.876 (dd, 1H), 7.60, −17.9 | 2.925 (dd, 1H), 8.01, −17.9 | 2.894 (dd, 1H), 7.90, −17.9 | 2.871 (dd, 1H), 8.01, −17.9 | 2.856 (dd, 1H), 7.95, −17.8 | 2.859 (dd, 1H), 7.89, −17.8 | 2.859 (dd, 1H), 7.90, −17.8 | 2.638 (dd, 1H), 5.33, −17.2 | |

| l-Arg | α | 4.334 (dd, 1H), 5.09, 8.73 | 4.407 (dd, 1H), 6.66, 7.59 | 4.311 (dd, 1H), 6.69, 7.57 | 4.324 (dd, 1H), 6.48, 7.79 | 4.324 (dd, 1H), 6.35, 7.95 | 4.331 (dd, 1H), 6.30, 8.02 | 4.304 (dd, 1H), 6.10, 8.06 | |

| β2 | 1.910 (dddd, 1H), 5.09, −14.0, 5.50, 11.0 | 1.822 (dddd, 1H), 6.66, −13.7, 11.1, 5.30 | 1.677 (dddd, 1H), 6.69, −13.7, 10.8, 5.48 | 1.700 (dddd, 1H), 6.48, −13.6, 10.7, 5.59 | 1.693 (dddd, 1H), 6.35, −13.8, 10.8, 5.55 | 1.708 (dddd, 1H), 6.30, −13.8, 10.8, 5.74 | 1.687 (dddd, 1H), 6.10, −13.8, 10.8, 6.04 | ||

| β3 | 1.779 (dddd, 1H), 8.73, −14.0, 10.7, 4.94 | 1.743 (dddd, 1H), 7.59, −13.7, 4.91, 11.1 | 1.657 (dddd, 1H), 7.57, −13.7, 4.99, 10.9 | 1.667 (dddd, 1H), 7.79, −13.6, 5.06, 10.8 | 1.670 (dddd, 1H), 7.95, −13.8, 4.86, 10.9 | 1.678 (dddd, 1H), 8.02, −13.8, 4.96, 10.9 | 1.661 (dddd, 1H), 8.06, −13.8, 4.79, 10.9 | ||

| β 2 | 1.640 (ddddd, 1H), 5.50, 10.7, −14.0, 6.88, 6.97 | 1.632 (ddddd, 1H), 11.1, 4.91, −13.7, 6.89, 6.94 | 1.462 (ddddd, 1H), 10.8, 4.99, −13.7, 7.15, 7.03 | 1.501 (ddddd, 1H), 10.7, 5.06, −13.0, 8.36, 5.62 | 1.506 (ddddd, 1H), 10.8, 4.86, −13.6, 7.30, 6.82 | 1.522 (ddddd, 1H), 10.8, 4.96, −13.7, 6.52, 8.68 | 1.495 (ddddd, 1H), 10.8, 4.79, −13.6, 5.01, 9.29 | ||

| γ3 | 1.644 (ddddd, 1H), 11.0, 4.94, −14.0, 6.82, 7.01 | 1.606 (ddddd, 1H), 5.30, 11.1, −13.7, 7.07, 6.94 | 1.420 (ddddd, 1H), 5.48, 10.9, −13.7, 7.12, 6.92 | 1.457 (ddddd, 1H), 5.59, 10.8, −13.0, 8.38, 5.72 | 1.456 (ddddd, 1H), 5.55, 10.9, −13.6, 7.22, 6.80 | 1.474 (ddddd, 1H), 5.74, 10.9, −13.7, 7.10, 6.42 | 1.460 (ddddd, 1H), 6.04, 10.9, −13.6, 6.11, 7.77 | ||

| δ2 | 3.183 (ddd, 1H), 6.88, 6.82, −13.7 | 3.175 (ddd, 1H), 6.89, 7.07, −13.9 | 3.079 (ddd, 1H), 7.15, 7.12, −11.7 | 3.103 (ddd, 1H), 8.36, 8.38, −11.3 | 3.106 (ddd, 1H), 7.30, 7.22, −11.3 | 3.114 (ddd, 1H), 6.52, 7.10, −13.6 | 3.091 (ddd, 1H), 5.01, 6.11, −14.4 | ||

| δ3 | 3.174 (ddd, 1H), 6.97, 7.01, −13.7 | 3.168 (ddd, 1H), 6.94, 6.94, −13.9 | 3.074 (ddd, 1H), 7.03, 6.92, −11.7 | 3.102 (ddd, 1H), 5.62, 5.72, −11.3 | 3.102 (ddd, 1H), 6.82, 6.80, −11.3 | 3.110 (ddd, 1H), 8.68, 6.42, −13.6 | 3.092 (ddd, 1H), 9.29, 7.77, −14.4 | ||

| l-Val | α | 4.214 (d, 1H), 5.88 | 4.050 (d, 1H), 8.15 | 4.052 (d, 1H), 7.99 | 4.054 (d, 1H), 8.12 | 4.060 (d, 1H), 8.04 | 4.049 (d, 1H), 8.15 | ||

| β | 2.149 (dqq, 1H), 5.88, 6.82, 6.86 | 1.932 (dqq, 1H), 8.15, 6.73, 7.76 | 1.922 (dqq, 1H), 7.99, 6.76, 6.75 | 1.917 (dqq, 1H), 8.12, 6.72, 6.72 | 1.927 (dqq, 1H), 8.04, 6.73, 6.75 | 1.909 (dqq, 1H), 8.15, 6.71, 6.76 | |||

| γ1 | 0.9147 (d, 3H), 6.82 | 0.8542 (d, 3H), 6.73 | 0.8462 (d, 3H), 6.76 | 0.8503 (d, 3H), 6.72 | 0.8562 (d, 3H), 6.73 | 0.8455 (d, 3H), 6.71 | |||

| γ2 | 0.9186 (d, 3H), 6.86 | 0.8440 (d, 3H), 7.76 | 0.8125 (d, 3H), 6.75 | 0.8119 (d, 3H), 6.72 | 0.8205 (d, 3H), 6.75 | 0.7967 (d, 3H), 6.76 |

| D | DR | DRV | DRVY | DRVYI | DRVYIH | DRVYIHP | DRVYIHPF | ||

| l-Tyr | α | 4.535 (dd, 1H), 5.11, 9.19 | 4.578 (dd, 1H), 6.37, 8.58 | 4.598 (dd, 1H), 6.18, 8.63 | 4.565 (dd, 1H), 7.00, 8.21 | 4.567 (dd, 1H), 6.58, 8.46 | |||

| β2 | 3.085 (ddd, 1H), 5.11, −14.1, 0.534 | 2.970 (ddd, 1H), 6.37, −13.9, 0.490 | 2.939 (ddd, 1H), 6.18, −14.0, 0.326 | 2.908 (ddd, 1H), 7.00, −13.9, 0.473 | 2.902 (ddd, 1H), 6.58, −14.0, 0.240 | ||||

| β3 | 2.864 (ddd, 1H), 9.19, −14.1, 0.401 | 2.826 (ddd, 1H), 8.58, −13.9, 0.483 | 2.809 (ddd, 1H), 8.63, −14.0, 0.352 | 2.832 (dd, 1H), 8.21, −13.9 | 2.805 (ddd, 1H), 8.46, −14.0, 0.195 | ||||

| δ | 7.079 (ddddd, 2H), 0.534, 0.401, 2.53, 8.34, 0.407 | 7.067 (ddddd, 2H), 0.490, 0.483, 2.02, 8.33, 0.364 | 7.044 (ddddd, 2H), 0.326, 0.352, 2.79, 8.34, 0.339 | 7.041 (dddd, 2H), 0.473, 2.28, 8.35, 0.326 | 7.026 (ddddd, 2H), 0.240, 0.195, 2.69, 8.44, 0.152 | ||||

| ε | 6.744 (ddd, 2H), 8.34, 0.407, 2.66 | 6.733 (ddd, 2H), 8.33, 0.364, 2.61 | 6.694 (ddd, 2H), 8.34, 0.339, 2.30 | 6.701 (ddd, 2H), 8.35, 0.326, 2.81 | 6.680 (ddd, 2H), 8.44, 0.152, 3.02 | ||||

| l-Ile | α | 4.186 (d, 1H), 6.45 | 4.082 (d, 1H), 8.33 | 4.046 (d, 1H), 8.64 | 4.044 (d, 1H), 8.43 | ||||

| β | 1.809 (dddq, 1H), 6.45, 4.25, 8.94, 6.84 | 1.747 (dddq, 1H), 8.33, 3.42, 8.98, 6.81 | 1.684 (dddq, 1H), 8.64, 3.50, 8.91, 6.87 | 1.684 (dddq, 1H), 8.43, 3.47, 8.96, 6.77 | |||||

| γ12 | 1.379 (ddq, 1H), 4.25, −13.6, 7.52 | 1.361 (ddq, 1H), 3.42,−13.6, 7.44 | 1.341 (ddq, 1H), 3.50, −13.6, 7.32 | 1.311 (ddq, 1H), 3.47, −13.5, 7.44 | |||||

| γ13 | 1.134 (ddq, 1H), 8.94, −13.6, 7.34 | 1.087 (ddq, 1H), 8.98, −13.6, 7.42 | 1.062 (ddq, 1H), 8.91, −13.6, 7.39 | 1.050 (ddq, 1H), 8.96, −13.5, 7.43 | |||||

| γ2 | 0.8531 (d, 3H), 6.84 | 0.8231 (d, 3H), 6.81 | 0.7604 (d, 3H), 6.87 | 0.7492 (d, 3H), 6.77 | |||||

| δ1 | 0.8218 (dd, 3H), 7.52, 7.34 | 0.7843 (dd, 3H), 7.44, 7.42 | 0.7691 (dd, 3H), 7.32, 7.39 | 0.7580 (dd, 3H), 7.44, 7.43 | |||||

| l-His | α | 4.601 (dd, 1H), 5.44, 8.19 | 4.827 (dd, 1H), 6.94, | 4.799 (dd, 1H), 6.22, 7.50 | |||||

| β2 | 3.237 (ddd, 1H), 5.44, −15.5, 0.823 | 3.178 (ddd, 1H), 6.94, −15.4, 0.699 | 3.101 (ddd, 1H), 6.22, −15.6, 0.679 | ||||||

| β3 | 3.121 (ddd, 1H), 8.19, −15.5, 0.781 | 3.117 (ddd, 1H), 6.97, −15.4, 0.692 | 3.020 (ddd, 1H), 67.50, −15.6, 0.678 | ||||||

| δ2 | 7.223 (ddd, 1H), 0.823, 0.781, 1.42 | 7.299 (ddd, 1H), 0.699, 0.692, 1.42 | 7.180 (ddd, 1H), 0.679, 0.678, 1.39 | ||||||

| ε1 | 8.576 (d, 1H), 1.42 | 8.600 (d, 1H), 1.42 | 8.512 (d, 1H), 1.39 |

| D | DR | DRV | DRVY | DRVYI | DRVYIH | DRVYIHP | DRVYIHPF | ||

| l-Pro | α | 4.339 (dd, 1H), 8.90, 5.56 | 4.337 (dd, 1H), 8.52, 4.77 | ||||||

| β2 | 2.253 (dddd, 1H), 8.90, −12.9, 7.69, 6.68 | 2.134 (dddd, 1H), 8.52, −12.8, 6.95, 8.13 | |||||||

| β3 | 1.954 (dddd, 1H), 5.56, −12.9, 6.81, 6.74 | 1.851 (dddd, 1H), 4.77, −12.78, 5.95, 6.72 | |||||||

| γ2 | 1.969 (ddddd, 1H), 7.69, 6.81, −12.6, 6.49, 7.27 | 1.898 (ddddd, 1H), 6.95, 5.95, −12.2, 6.36, 5.82 | |||||||

| γ3 | 1.958 (ddddd, 1H), 6.68, 6.74, −12.6, 6.88, 6.31 | 1.854 (ddddd, 1H), 8.13, 6.72, −12.2, 7.37, 7.38 | |||||||

| δ2 | 3.759 (ddd, 1H), 6.49, 6.88, −9.99 | 3.677 (ddd, 1H), 6.36, 7.37, −9.86 | |||||||

| δ3 | 3.501 (ddd, 1H), 7.27, 6.31, −9.99 | 3.493 (ddd, 1H), 5.82, 7.38, −9.86 | |||||||

| l-Phe | α | 4.386 (dd, 1H), 5.36, 6.94 | |||||||

| β2 | 3.100 (dd, 1H), 5.36, −13.8 | ||||||||

| β3 | 2.975 (dd, 1H), 6.94, −13.8 | ||||||||

| δ | 7.193 (dddd, 2H), 2.02, 7.69, 0.497, 1.16 | ||||||||

| ε | 7.250 (dddd, 2H), 7.69, 0.497, 1.47, 7.38 | ||||||||

| ζ | 7.178 (ddd, 1H), 1.16, 7.38 |

800 MHz, D2O/CD3OD (3:2). 1H NMR parameters generated by HiFSA analysis. Values represented as δH (ppm), (multiplicity, no. H), J (Hz).

The most substantial Δδ change was observed after the first AA chain elongation, with the Hα resonance moving from 3.966 to 4.315 ppm (Δδ = 0.349 ppm). This jump can be attributed to the chemical change from a carboxyl functional group to an amide, as the N–C backbone gets formed. The greatest change in the J values also occurred for Hα of the C-terminal AA after the addition of the subsequent AA. This was consistent with observations with other peptides performed in this study. Also, upon elongation of the dipeptide DR with Val to DRV, the vicinal couplings of Arg-Hβ2 and Arg-Hβ3 with Arg-Hγ2 and Arg-Hγ3 switched, suggesting that the side chain of Arg might rotate to a different conformation upon the addition of Val. The addition of Pro to the precursor hexapeptide led to the first observation of rotational conformers. The minor conformer (Table S3) observed in DRVYIHP represents approximately 6% of the population. As with natural 3, the population of the minor conformer could be determined to be approximately 4% via integration of a minor signal at 4.15 ppm (Figure S27). The observed population difference of 5.5 (case 3) vs 4.0% and can be explained by the change in solvent composition (D2O:CD3OD 3:2 vs 3:0.9) and concentration (9.5 vs 25 mM).

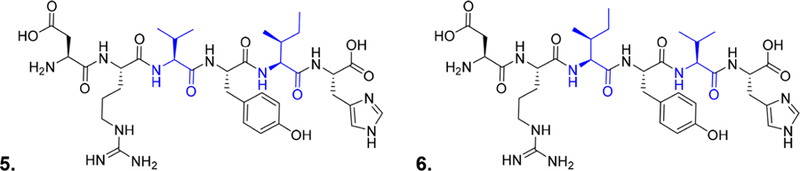

Challenge Case Study 5: AA Sequence Inversion.

To determine the ability of the HiFSA sequencing approach to detect subtle structural changes that are known to, or could, occur in peptides, several cases were generated as follows. The first challenge case involved a switch in the AA sequence that resulted in the equivalent of a single methyl group difference. Two peptides were custom synthesized representing the first six AAs of 3, one with the same sequence as compound 3, DRVYIH (5), and one with the translocation of l-Val and l-Ile, DRIYVH (6) (Figure 6). A standard QC test (HPLC and MS) as typically performed by laboratories, including custom peptide synthesis manufacturers, showed no distinguishable difference between the two peptides, casting doubt on the practice of reporting HPLC purity values for such compounds.

Figure 6.

Structures of DRVYIH (5) and DRIYVH (6).

The peptides were first analyzed in house by MS2 to confirm the peptide sequence. The collision energy was varied to study different fragmentations, but no significant differences between the two peptides could be observed for the fragment 802.42 m/z (Figures S42 and S43).

Next, the peptides were prepared at concentrations of 18 and 21 mM, respectively, in CD3OD (175 μL) and DMSO-d6 (50 μL), in 3 mm NMR tubes, for analysis at 800 MHz. Following acquisition and processing, the HiFSA profile of each peptide was generated (Table 12). A slight change in chemical shift was noted for every hydrogen (average Δδ = 0.03 ± 0.03 ppm), with obvious visual difference. However, the largest differences (~0.10 ppm) were observed in the region of the aliphatic hydrogens and methyl groups (0.5–2.0 ppm, Figure S44). A greater similarity was initially expected; however, when considering environmental effects of the secondary peptide structure, changes throughout the entire molecule can still be explained. However, the HiFSA profiles of the peptides remained consistent despite the AA translocation. The average observed ΔJ was 0.25 ± 0.53 Hz. This is most likely due to the structure not being affected by the inversion of Val for Ile in the hexapeptides.

Table 12.

DRVYIH (5) vs DRIYVH (6)a

|

δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals, J [Hz]) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRVYIH (5) | DRIYVH (6) | ||||

| l-Asp | α | 4.260 (dd, 1H, 4.24, 8.82) | l-Asp | α | 4.255 (dd, 1H, 4.25, 8.80) |

| β2 | 3.015 (dd, 1H, 4.24, −17.8) | β2 | 3.004 (dd, 1H, 4.25, −17.8) | ||

| β3 | 2.830 (dd, 1H, 8.82, −17.8) | β3 | 2.825 (dd, 1H, 8.80, −17.8) | ||

| l-Arg | α | 4.452 (dd, 1H, 5.49, 8.50) | l-Arg | α | 4.439 (dd, 1H, 5.56, 8.49) |

| β2 | 1.812 (dddd, 1H, 5.49, −13.7, 10.1, 6.02) | β2 | 1.803 (dddd, 1H, 5.56, −13.8, 10.1, 5.97) | ||

| β3 | 1.713 (dddd, 1H, 8.50, −13.7, 5.18, 10.4) | β3 | 1.706 (dddd, 1H, 8.49, −13.8, 4.98, 10.2) | ||

| γ2 | 1.631 (ddddd, 1H, 10.1, 5.18, −13.6, 4.46, 7.05) | γ2 | 1.625 (ddddd, 1H, 10.1, 4.98, −13.6, 6.98, 7.62) | ||

| γ3 | 1.610 (ddddd, 1H, 6.02, 10.4, −13.6, 7.00, 4.54) | γ3 | 1.602 (ddddd, 1H, 5.97, 10.2, −13.6, 7.48, 6.39) | ||

| δ2 | 3.185 (ddd, 1H, 7.05, 4.54, −12.4) | δ2 | 3.184 (ddd, 1H, 7.62, 6.39, −13.6) | ||

| δ3 | 3.205 (ddd, 1H, 4.46, 7.00, −12.4) | δ3 | 3.199 (ddd, 1H, 6.98, 7.48, −13.6) | ||

| l-Val | α | 4.210 (d, 1H, 7.39) | l-Ile | α | 4.241 (d, 1H, 7.91) |

| β | 2.030 (dqq, 1H, 7.39, 6.67, 6.77) | β | 1.794 (dddq, 1H, 7.91, 3.40, 9.20, 6.83) | ||

| γ1 | 0.9109 (d, 3H, 6.67) | γ12 | 1.482 (ddq, 1H, 3.40, −13.5, 7.51) | ||

| γ2 | 0.8942 (d, 3H, 6.77) | γ13 | 1.135 (ddq, 1H, 9.20, −13.5, 7.30) | ||

| l-Tyr | α | 4.656 (dd, 1H, 5.15, 8.95) | γ2 | 0.8514 (d, 3H, 6.83) | |

| β2 | 3.013 (dd, 1H, 5.15, −14.1) | δ1 | 0.8777 (dd, 3H, 7.51, 7.30) | ||

| β3 | 2.810 (dd, 1H, 8.95, −14.1) | l-Tyr | α | 4.665 (dd, 1H, 5.14, 9.05) | |

| δ | 7.079 (ddd, 2H, 2.87, 8.38, 0.195) | β2 | 3.022 (dd, 1H, 5.14, −14.2) | ||

| ε | 6.679 (ddd, 2H, 8.38, 0.195, 2.38) | β3 | 2.821 (dd, 1H, 9.05, −14.2) | ||

| l-Ile | α | 4.180 (d, 1H, 7.91) | δ | 7.081 (ddd, 2H, 2.55, 8.30, 0.415) | |

| β | 1.840 (dddq, 1H, 7.91, 6.83, 3.40, 9.20) | ε | 6.679 (ddd, 2H, 8.30, 0.415, 2.55) | ||

| γ12 | 1.555 (ddq, 1H, 3.40, −13.50, 7.51) | l-Val | α | 4.132 (d, 1H, 7.53) | |

| γ13 | 1.197(ddq, 1H, 9.20, −13.50, 7.30) | β | 2.068 (dqq, 1H, 7.53, 7.19, 6.33) | ||

| γ2 | 0.9425 (d, 3H, 6.83) | γ1 | 0.9696 (d, 3H, 7.19) | ||

| δ1 | 0.9074 (dd, 3H, 7.51, 7.30) | γ2 | 0.9696 (d, 3H, 6.33) | ||

| l-His | α | 4.737 (dd, 1H, 5.02, 8.45) | l-His | α | 4.731 (dd, 1H, 5.05, 8.46) |

| β2 | 3.309 (ddd, 1H, 5.02, −15.52, 0.893) | β2 | 3.311 (ddd, 1H, 5.05, −15.6, 0.568) | ||

| β3 | 3.152 (ddd, 1H, 8.45, −15.52, 0.628) | β3 | 3.151 (ddd, 1H, 8.46, −15.6, 0.602) | ||

| δ2 | 7.372 (dd, 1H, 0.893, 0.628) | δ2 | 7.369 (dd, 1H, 0.568, 0.602) | ||

| ε1 | 8.766 (d, 1H, 1.28) | ε1 | 8.756 (d, 1H, 1.41) | ||

AA switch of isoleucine and valine. 1H NMR parameters generated by HiFSA analysis.

Challenge Case Study 6: AA Absolute Configuration Switch.

The second challenge case involved a change in the absolute configuration of a single AA, i.e., comparing an epimeric pair of peptides. Epimerization or racemization can occur during peptide synthesis and design, and it can also be overlooked by usual QC methods.31,32 This applies particularly as the impact of the enantiomerism of a singular AA on the diastereomeric character, and thus, nuclear diastereotopism decreases as the size of a peptide increases. Considering that NMR is most commonly practiced as an achiral method, determining whether HiFSA sequencing could detect epimerization in peptides was an important feature to assess. However, it is important to keep in mind that achiral NMR cannot distinguish enantiomeric peptides, unless chiral NMR is applied, which was beyond the scope of the present study.

The underlying hypothesis was that, when comparing epimers, the overall secondary and/or tertiary structural changes lead to possibly small but notable changes in the chemical shifts. To represent this sort of case, compound 3 was compared to a peptide with the same AA sequence, except for the l-Tyr changed to d-Tyr (7). An LC−MS2 analysis showed a difference in retention time of 5.1 min for 3 vs 5.5 min for 7 (Figures S55 and S56). As expected, the MS showed no difference between the two peptides (Figures S57 and S58), while the MS2 showed a subtle difference in the intensities of the fragmentation between the two (Figures S59 and S60). Thus, LC and LC–MS would require the availability of reference materials of all diastereomeric variants of a peptide in order to be a suitable diagnostic tool, which, in QC/QA practice, is an unrealistic scenario

For NMR analysis, both peptides were prepared at a concentration of 26 mM in 135 μLof D2O and 40 μL of CD3OD in a 3 mm NMR tube. Their 1H NMR spectra were obtained at 800 MHz, and the HiFSA profiles were generated (Table 13). There was a notable difference in the chemical shift for every hydrogen signal, making the spectra of the epimers easily distinguishable even through visual comparison (Figure S61). The observed Δδ was 0.08 ± 0.10 ppm, and the ΔJ was 0.55 ± 0.61 Hz. The change from L to D AA altered the N–C peptide backbone leading to greater changes in the peptide spatial structure. This explains why the observed change in J is twice of that seen in the challenge case 5, reflecting primarily the changes in the J values of the Hα and Pro hydrogens. Additionally, the conformational populations differed in compound 7, where the minor conformer showed an abundance of 7%, greater than observed for compound 3 (Table S6).

Table 13.

Angiotensin II vs Angiotensin II with d-Tyra

|

δH (multiplicity, rel. integrals), J [Hz] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Tyr | d-Tyr | |Δδ| (ppm) | ||

| l-Asp | α | 4.209 (dd, 1H), 8.12, 5.33 | 4.295 (dd, 1H), 4.99, 7.76 | 0.086 |

| β2 | 2.778 (dd, 1H), 8.12, −17.2 | 2.976 (dd, 1H), 4.99, −18.0 | 0.198 | |

| β3 | 2.638 (dd, 1H), 5.33, −17.2 | 2.904 (dd, 1H), 7.76, −18.0 | 0.266 | |

| l-Arg | α | 4.304 (dd, 1H), 6.10, 8.06 | 4.367 (dd, 1H), 5.02, 8.61 | 0.063 |

| β2 | 1.687 (dddd, 1H), 6.10, −13.8, 10.8, 6.04 | 1.742 (dddd, 1H), 5.02, −13.7, 11.2, 5.73 | 0.055 | |

| β3 | 1.661 (dddd, 1H), 8.06, −13.8, 4.79, 10.9 | 1.660 (dddd, 1H), 8.61, −13.7, 4.87, 11.1 | 0.001 | |

| γ2 | 1.495 (ddddd, 1H), 10.8, 4.79, −13.6, 5.01, 9.29 | 1.569 (ddddd, 1H), 11.2, 4.87, −13.6, 6.81, 7.22 | 0.074 | |

| γ3 | 1.460 (ddddd, 1H), 6.04, 10.9, −13.6, 6.11, 7.77 | 1.524 (ddddd, 1H), 5.73, 11.1, −13.6, 6.85, 6.85 | 0.064 | |

| δ2 | 3.091 (ddd, 1H), 5.01, 6.11, −14.4 | 3.115 (ddd, 1H), 6.81, 6.85, −13.4 | 0.024 | |

| δ3 | 3.092 (ddd, 1H), 9.29, 7.77, −14.4 | 3.105 (ddd, 1H), 7.22, 6.85, −13.4 | 0.013 | |

| l-Val | α | 4.049 (d, 1H), 8.15 | 4.054 (d, 1H), 7.06 | 0.005 |

| β | 1.909 (dqq, 1H), 8.15, 6.71, 6.76 | 1.839 (dqq, 1H), 7.06, 6.77, 6.88 | 0.070 | |

| γ1 | 0.8455 (d, 3H), 6.71 | 0.6923 (d, 3H), 6.77 | 0.153 | |

| γ2 | 0.7967 (d, 3H), 6.76 | 0.6882 (d, 3H), 6.88 | 0.108 | |

| Tyr | α | 4.567 (dd, 1H), 6.58, 8.46 | 4.572 (dd, 1H), 7.25, 8.81 | 0.005 |

| β2 | 2.902 (ddd, 1H), 6.58, −14.0, 0.240 | 3.002 (ddd, 1H), 7.25, −13.9, 0.800 | 0.100 | |

| β3 | 2.805 (ddd, 1H), 8.46, −14.0, 0.195 | 2.823 (ddd, 1H), 8.81, −13.9, 0.800 | 0.018 | |

| δ | 7.026 (ddddd, 2H), 0.240, 0.195, 2.69, 8.44, 0.152 | 7.079 (ddddd, 2H), 0.800, 0.800, 2.72, 8.31, 0.456 | 0.053 | |

| ε | 6.680 (ddd, 2H), 8.44, 0.152, 3.02 | 6.752 (ddd, 2H), 8.31, 0.456, 2.25 | 0.072 | |

| l-Ile | α | 4.044 (d, 1H), 8.43 | 3.974 (d, 1H), 7.54 | 0.071 |

| β | 1.684 (dddq, 1H), 8.43, 3.47, 8.96, 6.77 | 1.668 (dddq, 1H), 7.54, 3.59, 9.08, 6.83 | 0.015 | |

| γ12 | 1.311 (ddq, 1H), 3.47, −13.5, 7.44 | 1.035 (ddq, 1H), 3.59, −13.4, 7.48 | 0.276 | |

| γ13 | 1.050 (ddq, 1H), 8.96, −13.5, 7.43 | 0.8841 (ddq, 1H), 9.08, −13.4, 7.26 | 0.166 | |

| γ2 | 0.7492 (d, 3H), 6.77 | 0.6280 (d, 3H), 6.83 | 0.121 | |

| δ1 | 0.7580 (dd, 3H), 7.44, 7.43 | 0.7048 (dd, 3H), 7.48, 7.26 | 0.053 | |

| l-His | α | 4.799 (dd, 1H), 6.22, 7.50 | 4.616 (dd, 1H), 5.86, 7.90 | 0.183 |

| β2 | 3.101 (ddd, 1H), 6.22, −15.6, 0.679 | 3.150 (ddd, 1H), 5.86, −14.1, 0.654 | 0.050 | |

| β3 | 3.020 (ddd, 1H), 67.50, −15.6, 0.678 | 3.054 (ddd, 1H), 7.90, −14.1, 0.574 | 0.035 | |

| δ2 | 7.180 (ddd, 1H), 0.679, 0.678, 1.39 | 7.235 (ddd, 1H), 0.654, 0.574, 1.42 | 0.054 | |

| ε1 | 8.512 (d, 1H), 1.39 | 8.575 (d, 1H), 1.42 | 0.063 | |

| l-Pro | α | 4.337 (dd, 1H), 8.52, 4.77 | 4.367 (dd, 1H), 8.17, 6.16 | 0.030 |

| β2 | 2.134 (dddd, 1H), 8.52, −12.8, 6.95, 8.13 | 2.150 (dddd, 1H), 8.17, −13.2, 4.97, 10.4 | 0.017 | |

| β3 | 1.851 (dddd, 1H), 4.77, −12.78, 5.95, 6.72 | 1.816 (dddd, 1H), 6.16, −13.2, 5.66, 8.23 | 0.035 | |

| γ2 | 1.898 (ddddd, 1H), 6.95, 5.95, −12.2, 6.36, 5.82 | 1.910 (ddddd, 1H), 4.97, 5.66, −12.1, 6.26, 7.60 | 0.012 | |

| γ3 | 1.854 (ddddd, 1H), 8.13, 6.72, −12.2, 7.37, 7.38 | 1.909 (ddddd, 1H), 10.4, 8.23, −12.1, 7.60, 5.78 | 0.055 | |

| δ2 | 3.677 (ddd, 1H), 6.36, 7.37, −9.86 | 3.703 (ddd, 1H), 6.26, 7.60, −10.0 | 0.026 | |

| δ3 | 3.493 (ddd, 1H), 5.82, 7.38, −9.86 | 3.561 (ddd, 1H), 7.21, 5.78, −10.0 | 0.068 | |

| l-Phe | α | 4.386 (dd, 1H), 5.36, 6.94 | 4.918 (dd, 1H), 5.58, 8.37 | 0.532 |

| β2 | 3.100 (dd, 1H), 5.36, −13.8 | 3.151 (dd, 1H), 5.58, −15.5 | 0.051 | |

| β3 | 2.975 (dd, 1H), 6.94, −13.8 | 3.090 (dd, 1H), 8.37, −15.5 | 0.115 | |

| δ | 7.193 (dddd, 2H), 2.02, 7.69, 0.497, 1.16 | 7.241 (dddd, 2H), 1.93, 7.65, 0.540, 1.35 | 0.048 | |

| ε | 7.250 (dddd, 2H), 7.69, 0.497, 1.47, 7.38 | 7.306 (dddd, 2H), 7.65, 0.540, 1.44, 7.47 | 0.056 | |

| ζ | 7.178 (ddd, 1H), 1.16, 7.38 | 7.240 (ddd, 1H), 1.35, 7.47 | 0.062 | |

1H NMR parameters generated by HiFSA analysis.

Assessing the Portability of HiFSA Generated NMR Profiles.

The spectra of 5 and 6 were QM-calculated at lower field strengths, 400 and 60 MHz, to determine if the compounds could be distinguished with these types of instruments (Figures S33 and S40). As hypothesized initially, 5 and 6 were readily distinguishable even at 60 MHz, especially in the aliphatic region (Figures S45 and S46). Additionally, the QM-calculated 400 MHz spectrum was nearly identical to the experimental data collected at 400 MHz for both samples (Figures S34 and S41), indicating that only very minor adjustments are needed to match unavoidable and practically occurring differences in the acquisition conditions (e.g., temperature, concentration). To assess this quantitatively, the QM-calculated data were optimized via iteration, using the experimental 400 MHz data, and then the originally QM-calculated data were compared to the final iteration result. For 6, the difference between the two was found to be negligible (Δδ 1.3 ± 1.1 ppb, ΔJ 52 ± 51 mHz).

Compound 6 was also subjected to a full spin analysis using the beta version of the CT software under development at NMR Solutions. A comparison of the chemical shifts and coupling constants extracted by this new tool to the values obtained by PERCH showed infinitesimal variation, as reported in the Supporting Information (Tables S4 and S5). The RMS for the variation in the extracted chemical shifts was 0.000032 ppm (0.032 ppb or 0.026 Hz), and 0.072 Hz for the coupling constants. Such small variations are typical for a thorough quantum mechanical spectral analysis of exactly the same experimental data.6 Notably, the RMS of the overall fit was 25% better in CT because of its more advanced line-shape optimization capabilities, as shown in the Supporting Information (Figures S35).

The HiFSA profiles of 3 and 7 were also used to evaluate the simulation at lower field strengths of 400 and 60 MHz (Figures S47 and S51). Similar to the challenge case 5, both peptides were still readily distinguishable even at 60 MHz (Figures S62 and S63). Additionally, for both samples, the 400 MHz spectrum QM-calculated from the 800 MHz HiFSA profile was already nearly identical to the experimental data collected at 400 MHz (Figures S48 and S53).

Compounds 3 and 7 were also assessed experimentally at different magnetic fields by preparing them at 32 and 64 mM, respectively, for analysis at 60 and 800 MHz. Compound 3 was prepared at a lower concentration due to limited sample quantity. Both samples were prepared at 5 mM in D2O, and the tubes were flame-sealed. The design of the 60 MHz NMR instrument required all spectra to be acquired at 305 K, instead of the standard 298 K used in most cryomagnetic spectrometers. Therefore, when the experimentally acquired spectra on the 60 MHz were compared to the QM-calculated 60 MHz spectra from the spectra originally acquired at 800 MHz and 298 K, there was an observed Δδ. This difference averaged from 110 ± 1.1 Hz for 3 and 60 ± 8.6 Hz for 7. This nearly linear Δδ could be explained by acquisition temperature differences between the instruments and/or the different molar concentration of the 3 vs 5 mm sample tubes used. The HiFSA profiles exhibited no other significant differences.

To address the difference in temperature, the 5 mm prepared samples of 3 and 7 were also analyzed at 800 MHz. The QM-simulation from 800 to 60 MHz was repeated for the spectra acquired at 305 K and compared to the experimentally collected spectra from the 60 MHz instrument. The difference between the QM-calculated and the experimentally collected spectra was negligible. The most observable difference was an expected deviation in ν, which was higher in the 60 MHz experimental data. The smaller v from the 800 MHz QM-calculated parameters is carried over when the QM-simulation is performed at lower frequencies. Therefore, fit of the QM-calculated data then requires optimization (δ and v) using the experimental data with J values fixed (Figures S49 and S54).

Collectively, this indicates that spectra QM-calculated from well-established HiFSA profiles at different field strengths are highly comparable to experimentally collected spectra. These outcomes also confirm that HiFSA sequencing generates fully portable HiFSA profiles that can be transferred to largely different field strengths and/or even adapted to varying experimental conditions. The portability of HiFSA peptide sequences and other HiFSA profiles is a key feature for the use of low-field NMR in pharmaceutical QC.

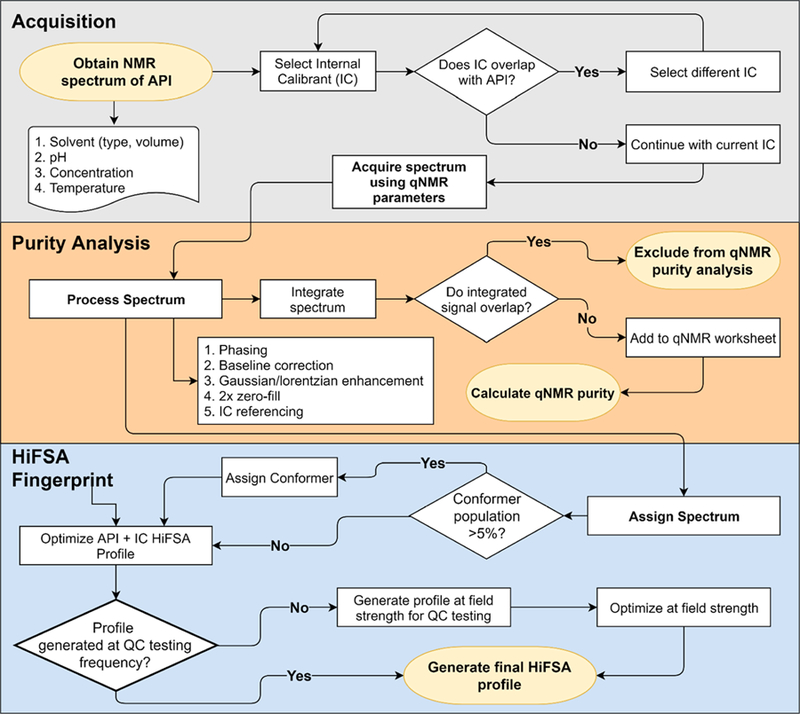

Proposed Procedure for QC of Peptides by HiFSA and Quantitative 1H NMR (qHNMR).

The above cases demonstrated the feasibility of understanding fully the 1D 1H NMR spectra of (bioactive) peptides by deciphering and assembling their AA spin systems using the QM-based HiFSA sequencing approach. The next logical step is incorporating the already demonstrated inherent quantitative nature of NMR to establish a general procedure for QC of peptides that can assess identity, quantity/strength, and purity as follows.

Step 1: NMR Acquisition.

For reference, see Figure 7. A sample of the API should be prepared using the solvent (type and volume), pH, sample concentrations, NMR tube size, and temperature that will be used for QC testing. Typically, an appropriate internal calibrant (IC) is selected that does not overlap with the signals of the API; external calibration (EC, ECIC) is also possible, depending on the overall scope.33 An NMR method is then designed with appropriate acquisition parameters utilizing quantitative NMR (qHNMR) guidelines.33–35 Sample preparation and acquisition should be repeated to achieve the intended reproducibility.

Figure 7.

Proposed workflow for the generation of a general QC protocol for pharmaceutically and biologically relevant peptides using qHNMR and HiFSA profiling. Population-based QM-qHNMR analysis paired with HiFSA profiling can replace INT-qHNMR analysis.

Step 2: qHNMR Processing.

Following acquisition, the spectrum is processed using appropriate phasing, baseline correction, ≥ 2× zero-fill, IC/EC/ECIC referencing, peak peaking, and signal integration techniques. Appropriate nonoverlapping signals for both the API and the calibrant are then selected for integration and calculation of qHNMR purity, e.g., using available spreadsheets.33 In case of signal overlap, peak-fitting methods (PF-qHNMR) can be utilized to improve the achievable accuracy of quantitation compared to 646 measuring integrals

Step 3: Generation of a HiFSA Fingerprint.

The portable HiFSA profile of the peptide is then generated using the processed spectrum. All major conformers, at a practically 650 feasible threshold of those with >5% population, should be included, and that ratio should be observed for variation during subsequent validation efforts. The IC is added to the HiFSA fingerprint as an additional species via the spin system descriptors and included in the calculation and iteration process. If the field strength used for QC is different than the one used for HiFSA profile creation, the QM simulation and subsequent iteration will involve the appropriate field strength and allow for subsequent matching with the experimental data obtained at that field strength. Until experimental conditions can be matched with high precision across different NMR instrument designs, especially when comparing benchtop permanent vs cryomagnet instruments, iteration of experimental data at the desired lower field are typically required to optimize suitability of the HiFSA profiles for the QC process.

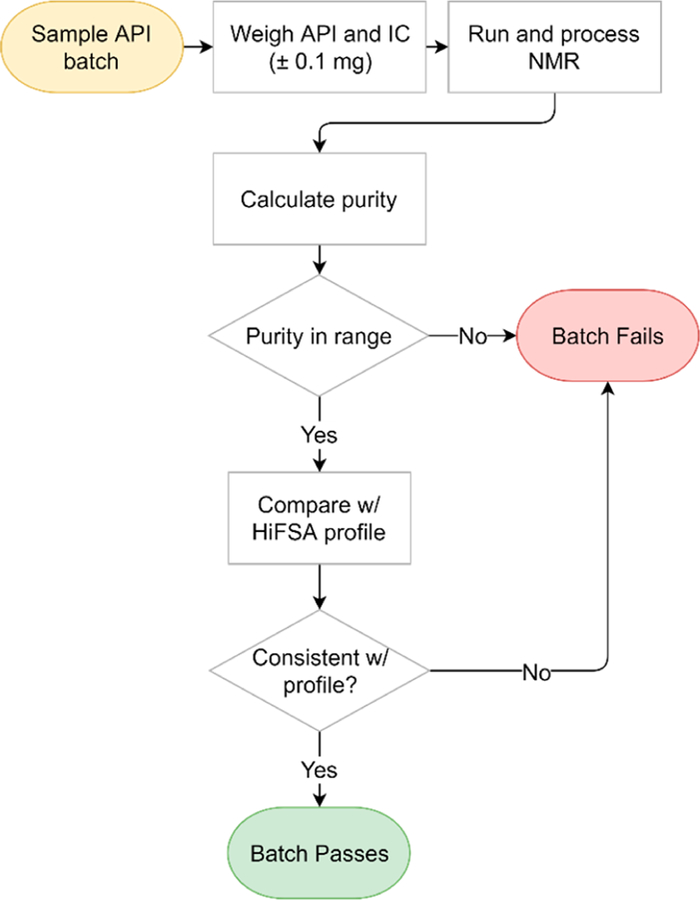

Step 4: QC Workflow.

Once the HiFSA profiles have been setup with appropriate SOP documentation, direct application to QC workflow and batch testing can begin. The SOP documentation should include the desired sample concentration (API and IC/EC/ECIC), NMR solvent type and volume, acquisition parameters, processing parameters, signals used for qHNMR analysis, and acceptable purity range. The workflow can be outlined as follows (Figure 8): (1) sample API batch and weigh API and IC accurately, within ±0.01 mg of established protocol, and record values. (2) Add samples to NMR tube with accurately measured NMR solvent; cap and seal the tube appropriately. (3) Place sample into NMR instrument, select method file, and acquire the spectrum. (4) Import raw NMR data into processing software and apply postacquisition processing. (5) Compare experimentally collected spectra to the HiFSA profile to establish final match results, likely consistent (green), questionable (yellow), or no match (red). (6) Input weight, MW, and integration values into the qHNMR worksheet for purity calculation. (7) Record both match results and %purity values and verify that they are within validated QC thresholds. Mark the batch as passed or failed accordingly.

Figure 8.

Workflow for QC testing by qHNMR and HiFSA profile.

QM-qHNMR Improves Accuracy in Purity Analysis.

IC-qHNMR is a well-established and metrologically accepted method for absolute purity determination by NMR. It lends itself to ready adoption in a manufacturing environment, with minimal classical NMR training requirements. However, IC-qHNMR is limited by its dependence on integration. This applies especially when a high degree of spectral overlap, as commonly observed in lower field spectra, limits available regions for clean integration (“peak purity”). This situation can be improved or even resolved by applying HiFSA profiles through quantum mechanical-based qHNMR (QM-qHNMR). 36,37 In the case of signal overlap, HiFSA can utilize the additional information coming from the quantum mechanical relations (frequencies and intensities including higher order effects) between the transitions within the individual spin systems to determine individual line intensities with QM precision. Thus, instead of fitting only individual peaks using line frequency assumption, as deconvolution methods employ, the QM/HiFSA fit of the qHNMR spectra depends only on the correctness of the chemical shifts and coupling constants, which have been established in a prior step. This means fewer variables, less ambiguity, and thus, better defined quantitative measures and more accurate results. In this approach, purity is determined using the population QM-calculated for the IC and the API, without any need for integration.

To demonstrate the feasibility of the QM-qHNMR approach for peptides, two examples were prepared, 4.41 mg of the dipeptide DR with 3.22 mg of DNBA as IC, and 3.39 mg of the pentapeptide DRVYI with 1.31 mg of DNBA as IC. Both samples were prepared with 175 μL of DMSO-d6 in 3 mm NMR tubes, the NMR spectra were acquired at 400 MHz and processed following the abs-qHNMR protocol.33 The purity of DR was determined by two methods of deriving the quantitative measures, integration, and HiFSA; INT-qHNMR gave 48.9%, whereas QM-qHNMR resulted in 43.7% purity. The purity of DRVYI was determined to be 73.8% by INT-qHNMR and 64.9% by QM-qHNMR. In both cases, the purity reported by QM-qHNMR was lower than the INT-qHNMR-based value. This difference is likely due to QM-qHNMR utilizing the entire spectrum for analysis, whereas INT-qHNMR is restricted to signals that are considered to be nonoverlapping. However, as the underlying peak purity assumption is typically based on consistent stoichiometric integration of the signals used for quantitation, this may not hold. In fact, QM-qHNMR by nature can serve as a cross-validation method for peak (im)purity in qHNMR and, therefore, is plausibly the more critical and accurate quantitation method.

One caveat of performing QM-qHNMR is that the accuracy of the analysis depends on the line shape and, thus, shimming quality; deviations from pure Lorentzian and/or Lorentzian–Gaussian line shapes make the iterative HiFSA fitting of experimental lineshapes susceptible to shimming artifacts. In practice, modern automated gradient shimming routines, or careful classical manual shimming, can overcome such limitations in routine operation. As integration ignores line shape and uses relatively wide integration ranges, INT-qHNMR is insusceptible to this spectral deficiency, but this is overcompensated by limitations in selectivity. However, it shall be noted, that suboptimal line shape affects all (q)NMR outcomes and is counterproductive for both qualitative (signal splitting, coupling constant accuracy) and quantitative (precision and accuracy) purposes. Both int- and QM-qHNMR depend equally on the purity of the internal control, which, in the present study, was a validated reference material of 99.5% purity.

Another limitation of QM-based quantitation arises when the software tool, such as PERCH, restricts the involved line shape optimization to a single Gaussian/Lorentzian ratio. This can lead to a systematic error, especially when comparing spin particles with intrinsically very different line shapes and dynamics, such as aromatic vs aliphatic analytes. While being beyond the scope of the present study, this gap is being filled by the CT software tool, which allows for spin particle-specific line shape optimization, as shown for peptide DRIYVH in Figure S35.

The absolute qHNMR purities of both peptides (43.7 and 64.9%) was substantially lower than the HPLC purities of >98% declared in the analysis certificates provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific. It is a well-established fact that HPLC typically fails to represent accurately the presence of structurally unrelated substances, such as solvents and/or other types of contaminants that are transparent to UV and other hyphenated detectors.33 In fact, the sample of DR was found to contain 3.8% residual DMSO, which HPLC was unable to detect. While additional gaps in the mass balance of synthetic and natural organic compounds can generally be attributed to residual water, impurities from chromatography (e.g., silica including RP-18) and/or inorganic matter are also possible. Additionally, as most synthetic peptides require a counterion, TFA is frequently encountered in these compounds. The presence of TFA in the samples of DR and DRVYI was confirmed through 19F NMR, where TFA was observed at −74.4 ppm and −75.8 ppm, respectively. Variability of chemical shift in the presence of TFA (e.g., by pH) is anticipated and was within expectation due to substrate topology, concentration, and electronic environment.38,39 Future applications should consider chloride and acetate as common ions.

CONCLUSIONS

HiFSA Sequencing Impacts Pharmaceutical QC.

The effects on patients and health set aside, product recalls can exert significant impact on both patients and the healthcare industry, including financial loss, damaged reputation, and effects on the supply chain. Typical recalls involve preventable errors in QC/QA processing. Especially concerning are Class I recalls, which are defined as health hazard situations that could possibly lead to serious adverse health consequences or even death.40 The top-five reasons for a Class I pharmaceutical recall include super or subpotent formulations, particulate contamination, contamination of the API, sterility failure in injectable formulations, and contamination of solids with molecules that have considerable vapor pressure (e.g., acetaminophen with 2,4,6-tribromoanisole).41 Falling into a different category, one of the more historically recognized cases was the recall of heparin in 2008.42 The recall was due to adulteration with oversulfated chondroitin sulfate, a “heparin-like” contaminant. The recall spurred major changes in QC procedures, notably including the application of NMR to product verification. Heparin also represents an exemplary case of a pharmaceutical product that is widely used but relatively poorly understood both structurally and biologically, while still best verified through QC methods, such as NMR. The strength of NMR in this context was its orthogonal character and more universal detection ability, targeting all hydrogen containing analytes.

Compared to the structural gamut of APIs, peptides and their constituent AAs represent a rather challenging class of compounds to fully characterize. In addition, peptides are greatly affected by even small structural changes through biological or chemical property changes, especially when considering rotamer and conformer effects that commonly occur even in small peptides. This is exemplified by both 1 and 2, which exhibit distinct conformational populations due to their flexibility. Common QC methods, such as HPLC and MS, cannot typically characterize conformational populations, which are directly related to primary structure. These methods may also fail to detect impurities, especially structurally unrelated unknowns, solvents, sorbents, and water. Even minor impurities, such as residual solvents, can impact pharmaceutical products in many ways by affecting stability, consumer rejection, allergic reactions, or even efficacy.

In addition, with the advancement in NMR instrumentation, including benchtop NMR instruments, it is possible to condense the burden of peptide QC efforts to LC(−MS) and NMR experiments only. Melanson et al. demonstrated purity determination of a standard peptide angiotensin II using a combination of quantitative 1H NMR (qHNMR) and LC−MS/MS.38 The counterion TFA was also quantitated through the use of a fluorinated internal standard and 19F-qHNMR. Therefore, since qHNMR can confirm both identity and absolute purity, using benchtop NMR instruments, NMR could be adopted for the QC of peptides in a manufacturing environment. Moreover, the combination of qHNMR and LC–MS, as demonstrated by Palaric et al., was used to quantitate amino acids in food supplements.43 The combination of qHNMR and LC–MS/MS may represent a different route for quantification of complicated mixtures where HiFSA may not be applicable.

Structural Specificity of HiFSA-Based QC.

In addition to addressing purity, QC methods also must address identity. The qHNMR approach not only solves the specificity challenges of AA and peptide identification and detection, but also provides simultaneous access to quantitative information. As demonstrated by Luan et al. through their qHNMR application to thiopeptcin, qHNMR is comparable in quantification to a customary mass balance method for the QC of peptdes.44 However, qHNMR takes less time to carry out.

Analogous to the case of the polysaccharide, heparin, small structural changes in peptides can also lead to effects on activity, safety, or physical chemical properties, such as solubility or bioavailability. One such example is that of the α-mating factor, where the configuration of one AA (His) can be switched from L to D and result in a lack of activity due to altered binding to the membrane proteins.45 Conformational effects from peptide epimerization can be seen, as demonstrated in this study, using 3; the population of the minor conformer changed upon the switch of l-Tyr for d-Tyr, something that was only observed by NMR. Most likely, other conformational effects may be present; however, further exploration of this aspect is beyond the scope of this work. Additionally, as part of the present study of configuration changes, LC–MS was capable of detecting the difference that occurred in challenge case 6; however, LC–MS, was unable to catch the inversion of AAs in challenge case 5.