Abstract

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number (CN) and damage in circulating white blood cells have been proposed as effect biomarkers for pollutant exposures. Studies have shown that mercury accumulates in mitochondria and affects mitochondrial function and integrity; however, these data are derived largely from experiments in model systems, rather than human population studies that evaluate the potential utility of mitochondrial exposure biomarkers. We measured mtDNA CN and damage in white blood cells (WBCs) from 83 residents of 9 communities in the Madre de Dios region of the Peruvian Amazon that vary in proximity to artisanal and small-scale gold mining. Prior research from this region reported high levels of mercury in fish and a significant association between food consumption and human total hair mercury level of residents. We observed that mtDNA CN and damage were both associated with consumption of fruit and vegetables, higher diversity of fruit consumed, residential location, and health characteristics, suggesting common environmental drivers. Surprisingly, we observed negative associations of mtDNA damage with both obesity and age. We did not observe any association between total hair mercury or, in contrast to previous results, age, with either mtDNA damage or CN. The results of this exploratory study highlight the importance of combining epidemiological and laboratory research in studying the effects of stressors on mitochondria, suggesting that future work should incorporate nutritional and social characteristics, and caution should be taken when applying conclusions from epidemiological studies conducted in the developed world to other regions, as results may not be easily translated.

Keywords: Amazon, Peru, DNA damage, WBC, Mercury, Diet, Epidemiology

Introduction

Mitochondrial function and integrity are critical to human health. A growing body of literature has identified multiple pathways through which mitochondria can be compromised, in particular, from pollutant exposures (Martinez and Greenamyre 2012; Meyer et al. 2013; Brunst et al. 2015). Inference on the degradation of mitochondria following exposure to toxicants such as organic chemicals, particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and cationic metals, has drawn largely upon controlled laboratory experiments using cell lines, model organisms or animal models (Bucio et al. 1999; Cakir et al. 2007; Karouna-Renier et al. 2014; Sanders et al. 2014a; Sanders et al. 2014b). This study examines factors influencing mtDNA copy number (CN) and damage in a randomly selected human population in the Peruvian Amazon living in an area with extensive mercury contamination due to artesanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM). Mercury exposure in the region is believed to predominantly result from contaminated fish consumption, due to mercury’s ability to bioacculate in aquatic ecosystems (Diringer et al. 2015; Wyatt et al. 2017a).

Methylmercury (MeHg), the predominant mercuric form in contaminated fish, poses major health risks (Atchison and Hare 1994; Grandjean et al. 1998; Crespo-Lopez et al. 2009; Carocci et al. 2014; Weinhouse et al. 2017) and may serve as an important antagonist of mitochondrial health. Although the mechanisms are not always clear, MeHg is known to concentrate in the mitochondria (Atchison and Hare 1994; Bucio et al. 1999), reacting with selenol and sulfhydryl groups on many proteins, as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione, causing cellular disruption. Inhibition of antioxidant enzymes and electron transport chain proteins can lead to increases of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Stohs and Bagchi 1995). ROS can react with DNA, causing single and double stranded breaks, abasic sites and base oxidation. In addition, mercury (Hg) may inhibit DNA repair enzymes (Crespo-Lopez et al. 2009). MeHg is also considered the most genotoxic Hg compound (Crespo-Lopez et al. 2009). The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) classifies it as a possible human genotoxicant (ATSDR 1999) as studies have documented DNA damage in the nuclear genome from MeHg exposure in multiple species (Barcelos et al. 2012; Mohmood et al. 2012; Pieper et al. 2014), including humans (Franchi et al. 1994; Amorim et al. 2000).

A variety of studies have documented effects of Hg and MeHg on mitochondrial form and function (Atchison and Hare 1994; Carocci et al. 2014). Laboratory studies have shown methyl mercuric chloride to induce ROS and reduce function of human lymphocytes (Shenker et al. 2002). In human neural cells, MeHg toxicity was found to be dose dependent and induced apoptosis at 0.1μM after 24 hours (Toimela and Tähti 2004); these and other reported effects are likely due in significant part to its affinity to selenol (Aschner and Syversen 2005) and thiol group-containing compounds (Hastings et al. 1975) such as glutathione (Kung et al. 1987; Rocha et al. 1993). However, to date, only three studies have examined the potential for Hg to affect mtDNA. Total Hg in fur and blood of wild bat was weakly associated with mtDNA damage in wing punches (Karouna-Renier et al. 2014). Alterations in mtDNA damage and mtDNA CN resulted from inorganic Hg (iHg) and MeHg exposures in laboratory experiments with the nematode model C. elegans (Wyatt et al. 2016; Wyatt et al. 2017b). In these laboratory experiments, mtDNA damage increased with HgCl2 exposure, as did nDNA damage. MeHg exposure led to increased mtDNA damage at 1μM, but surprisingly, decreased damage at 5μM. Perhaps most strikingly, the amount of mtDNA damage after hydrogen peroxide exposure was significantly increased by pre-exposure to either inorganic or organic mercury (Wyatt et al. 2017b).

These and other studies highlight the inherent complexity between mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage. MtDNA biogenesis and degradation regulate mitochondrial CN, and along with damage and repair determine steady-state mitochondrial DNA damage (mtDNA damage). MtDNA damage and CN are equilibrium values. In any given cell, mtDNA damage occurs both as a result of both endogenous and exogenous stressors, and is removed both by DNA repair (when possible) and mitophagy (Alexeyev et al. 2013; Bess et al. 2013; Scheibye-Knudsen et al. 2015). Damage can also be diluted by mtDNA biogenesis, which acts in concert with mitophagy to regulate mtDNA CN. Similarly, mitochondrial stress can trigger both mtDNA replication and degradation (Meyer et al. 2017). Finally, any changes in the half-lives of the various populations of cell types that “WBCs” comprise could lead to alterations in these parameters, since the removal and replacement of cells implies replacement of mitochondrial genomes. Few studies have simultaneously examined the different and potentially combinatorial effect of multiple variables on mtDNA parameters.

In addition to MeHg, emerging epidemiological evidence suggests that mitochondria are affected by a variety of environmental factors, with many studies suggesting mtDNA biomarkers be used as estimates for pollutant exposure (DiMauro and Davidzon 2005; Cakir et al. 2007; Hou et al. 2010; Martinez and Greenamyre 2012; Hou et al. 2013; Meyer et al. 2013; Brunst et al. 2015; Zhong et al. 2016). Tobacco use has been associated with mitochondrial damage to bronchoalveloar lavage tissues (Ballinger et al. 1996) and buccal cells (Tan et al. 2008); air pollution with decreased mtDNA CN (Hou et al. 2010; Hou et al. 2013); and rotenone exposure with greater mtDNA damage in skeletal muscle (Sanders et al. 2014a). However, results from human studies are not always consistent, with air pollution also associated with higher mtDNA CN (Zhong et al. 2016). Furthermore, non-pollutant factors such as diet may affect mitochondrial health (Meyer et al. 2018).

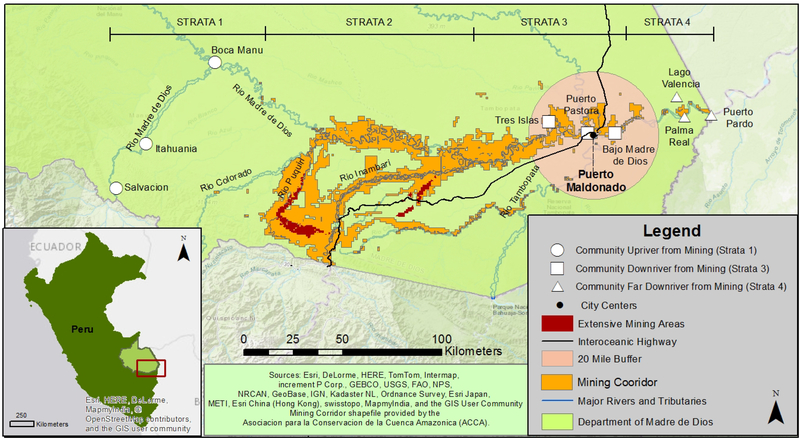

The primary goal of this study was to test whether high levels of MeHg exposure, inferred from total hair Hg, were associated with increased mtDNA damage (lesions per 10 kilobase pairs [kb]) or altered mtDNA CN per cell in an Amazonian population living in Madre de Dios (MDD), Peru. A secondary goal was to test the possible effects of other variables including dietary consumption patterns, residential location, and nutritional status. Data are from a comprehensive Hg exposure assessment study in communities located in the MDD River watershed, which is heavily impacted by ASGM (Figure 1). Prior research demonstrated that a third of carnivorous fish sampled in the watershed exceeded WHO standards (Diringer et al. 2015) and over 80% of inhabitants living along the river have total hair Hg levels that exceed USEPA guidelines of 1.2 μg/g with participants Hg levels ranging from 0.2μg/g – 14.5 μg/g (average of 3.5 μg/g, (Wyatt et al. 2017a). Therefore, this study specifically tests the relationship between MeHg exposure with mtDNA damage and CN in WBCs in a high fish-consuming population living both downriver and upriver from ASGM (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Project Site Map.

Communities sampled upriver from mining are represented as white circles (strata 1); communities sampled downriver from mining are white squares (strata 3) and communities sampled far downriver from mining are white triangles (strata 4). The capital city of Puerto Maldonado (PEM) is portrayed as a black dot and is the most urbanized city in the region, with its 20 mile radius shown in salmon. Twenty miles represents a distance in which the Puerto Maldonado can be reached within 1–2 hours. Mining corridor demonstrates land concessioned for mining (orange), while red represents extensively mined areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Design

Data were collected in the southern Amazon region of Madre de Dios (MDD), Peru. MDD is undergoing major environmental and demographic change due to road construction, urbanization and ongoing ASGM, which has led to widespread exposure to Hg(Diringer et al. 2015; Wyatt et al. 2017a), changes in diet and nutritional status (Feingold 2016), and increased vector-borne disease risk (Salmon-Mulanovich et al. 2015; Sanchez et al. 2017). Communities selected for this study were located along the Madre de Dios River, characterized as primarily rural with basic infrastructure and variable access to urban areas and local transportation networks (Supplemental Table I). Human data collection is described in (Wyatt et al. 2017a). Briefly, we used a two-stage cluster sampling approach to select 15 (of 26) communities along the Madre de Dios River, and a minimum of four households per community to obtain a minimum sample of 20 individuals (adults and children) per community. Community selection was stratified according to relative location to ASGM, which is concentrated at the confluence of the Colorado and Madre de Dios Rivers (Figure 1): 1) Upstream of ASGM (presumed low Hg exposure); 2) Between the Colorado and Inambari Rivers (high ASGM activity); 3) Between Inambari and Tambopata Rivers (moderate ASGM activity); and 4) Far downriver of ASGM. At the time of sampling (June-July 2013), selected communities in strata 2 could not be visited due to social unrest, resulting in three communities from strata 1, 3 and 4 being visited.

Each household enrolled was administered a survey (primarily to the female household head), which included questions pertaining to food consumption, migration, and occupation. 197 participants were enrolled, of whom 83 adults provided hair samples for Hg testing and blood samples for mtDNA processing. Human subjects’ approval was obtained from the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit-6 Committee of Human Subjects Research located in Lima, Peru (IRB# NAMRU6.2013.0012).

2.2. Sample collection

To measure total hair Hg, hair samples were collected in triplicate by cutting a tuft of hair from the occipital region of the scalp with stainless steel scissors and storing the samples in separate plastic bags. The most proximal 2-cm segment was analyzed for total Hg content by direct combustion atomic absorption spectrometry (Milestone DMA-80), as described previously (Wyatt et al. 2017a). The measured hair Hg (total Hg) may approximate dietary Hg exposure as studies involving populations with high fish consumption have demonstrated that approximately 90% of Hg found in hair is MeHg; however, it is uncertain how mixed exposure with iHg may influence total hair Hg levels (Akagi et al. 1995; Berglund et al. 2005; Cernichiari et al. 2007). Hemoglobin levels were determined from a finger prick using a Hemocue Hb201+. To assess mtDNA CN and damage, venous blood was collected in a BD PaxGene tube (Catalogue number: 761115). Blood samples were stored at −20°C within four hours of collection for a period of four to seven days before being transferred to a −80°C freezer for long-term storage until analysis.

2.3. DNA isolation and quantification

Frozen whole blood samples were thawed in a 37°C water bath and then immediately processed at Duke University. PAXgene Blood DNA kits (QIAGEN) were used to extract high molecular weight DNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Catalogue number: 761133). DNA yield and purity were analyzed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (ThermoFisher). Sample DNA was quantified with PicoGreen (ThermoFisher P7589) and samples were diluted to 3ng/μL in 0.1X TE buffer for use in long amplicon Polymerase Chain Reaction (LA-PCR) and real time PCR assays, as previously described (Gonzalez-Hunt et al. 2016).

2.4. mtDNA copy number and damage

We assessed mtDNA CN using standard curve-based real time PCR by preparing serial dilutions of the plasmid to create a standard curve to then calculate absolute mitochondrial CN (Gonzalez-Hunt et al. 2016). The real-time PCR reactions contained 2 μL of 3 ng/μL total DNA per reaction, for a total of 6 ng. Assuming that each WBC contained 6 pg total DNA, we estimate that 1,000 WBCs were used to calculate mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage.

A LA-PCR assay (Gonzalez-Hunt et al. 2016) was used to measure mtDNA damage, which detects DNA damage such as bulky adducts and single strand breaks that can detectably inhibit the progression of the DNA polymerase used in the PCR amplification reaction (Ponti et al. 1991). More-damaged templates are less well-amplified, and the decrease in amplification is converted mathematically to lesions per 10 kilobases of mtDNA. mtDNA damage results were normalized internally to mtDNA CN. Both mtDNA CN and damage endpoints are reported to a “low risk” reference group of five individuals who were chosen based on factors that we predicted would result in low mtDNA damage. These individuals were non-smokers, neither obese nor stunted and ranged from 12 to 27 years old with hair Hg levels from 1.3ppm-2.5ppm (3.5 ppm was the average, and 14.5 the maximum, in the full sample). mtDNA damage in WBCs was calculated relative to the reference group which is defined as “undamaged;” thus, negative damage signifies less damage than the average of the selected reference group.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

mtDNA CN and damage were the primary outcomes of interest. The primary exposure of interest was total hair Hg level with nutrition as a potential modifier. Since nutrition and diet are heterogeneous across the study area due to the remoteness of certain communities, community location was also considered in the analysis. Both mtDNA CN and total hair Hg were log10 transformed to normalize the distribution. Total hair Hg (continuous) and Hg exposure group (categorical) were evaluated based on different recommended guidelines to reduce the likelihood of adverse health outcomes in vulnerable populations. Several categories were considered to identify a high Hg exposure group. We decided to use the relatively high Canadian regulatory threshold of 6μg/g, in order to examine the effect of the highest levels of exposure, rather than the U.S. National Research Council and World Health Organization limits of 1.2 μg/g and 2.0 μg/g, respectively WHO (Group 2004).

To assess potential environmental impacts on mtDNA CN and damage, we evaluated associations with the following covariates: Residential location, defined as distance from the capital city, Puerto Maldonado (PEM) (within 20 miles-Near/Far) and from ASGM (Upriver/Near PEM/Downriver); Occupation, categorized as manual (i.e., mining, logging, agriculture), domestic (i.e., housewife, student), and other/unknown primary employment; Nutritional status, which included anemia, body mass index (BMI), obesity (Yes/No, BMI>30), and stunting (height-for-age z-score, HAZ<−2); Food consumption, defined as frequency and diversity of fruits, vegetables, animal and other proteins, fish, starch and overall diet diversity; and smoking status, categorized as daily, occasionally, never, and unknown. Variables are described in supplemental materials along with justifications for inclusion in model testing (Supplemental Table I).

Food frequency was determined by recording if persons in the household ate certain food items daily, weekly, sometimes or seasonally. Frequency of consumption was determined by summing the number of food items the household ate either daily or weekly. Diet diversity was determined by summing the number of food items the family stated they ate in each food group as listed above. Consumption of fruit and vegetables, frequency and diversity, was categorized low, medium and high based on first and third quartiles of the data distribution (Supplemental Table I). The list of foods considered in the study can be found in the supplemental material (Supplemental Table II).

Multivariate models were developed to test the relationship of total hair Hg content with mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage. All models were adjusted for age and sex with models being run for each variable of interest and a second set of models stratified by community location (near vs. far from PEM). All models were additionally adjusted for correlated observations within household (for mtDNA CN) or within community (for mtDNA damage), based on improved model fit using Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) goodness of fit criteria. Percent change in mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage is computed as the ratio of predicted values for variable categories times 100. Interactions between total hair Hg content with age, sex, residential location and food consumption were evaluated to determine effect modification. All analyses were conducted using R (v0.99.491).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive characteristics and distributions of key covariates

mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage did not vary significantly by categories of total hair Hg levels in unadjusted analysis (Table I). Alternative thresholds of mercury exposure also did not indicate significant differences in mtDNA CN or damage (Supplemental Figure 1). In addition, mtDNA CN and damage did not vary across other key covariates measured, including age, sex, smoking status, nutritional status, and diet (Table I). However, heterogeneity did exist in some individual and household characteristics by community location in relation to ASGM (Table II); including significant differences in mtDNA damage and vegetable consumption and borderline significant differences in smoking status and stunting (Table II). Individuals living near PEM had significantly less mtDNA damage than individuals living upriver or far downriver of ASGM (p<0.0001). Individuals living near PEM (vs. upstream or far downstream of ASGM) were also less likely to be chronically malnourished (9% stunted compared to 36% overall, p=0.054), older (52% vs. 28% over age 40), more likely to smoke (20% vs. 10% daily smokers), and more likely to be obese (40% vs. 22% obese), although some of these comparisons did not achieve statistical significance at the 0.05 level. With the exception of diversity of vegetable consumption, for which communities far upstream of ASGM had much higher diversity than other communities (p=0.0425), food consumption patterns were relatively similar. Interestingly, total hair Hg levels were equally high across the study region with only 9.6% of the population having total hair Hg levels below the USEPA threshold of 1.2 μg/g and 16% surpassing the Canadian threshold of 6 μg/g.

Table I.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of Log10 (mtDNA CN) and mtDNA damage/10kb across each variable assessed.

| INDIVIDUAL DATA a | Log10(mtDNA CN) |

mtDNA damage/10kb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Overall | 83 | 5.499 (5.226 – 5.669) | 0.097 (−0.652 – 0.971) | |||

| Hair Mercury Level(μg/g) | <6 | 70 | 5.501 (5.485 – 5.517) | 0.084 (0.154 – 0. 154) | ||

| >=6.0 | 13 | 5.491 (5.466 – 5.515) | 0.164 (−0.105 – 0.433) | |||

| Age | 12–28 | 38 | 5.495 (5.475 – 5.515) | 0.142 (0.042 – 0.243) | ||

| 28–44 | 26 | 5.496 (5.467 – 5.526) | 0.131 (−0.005 – 0.267) | |||

| 45+ | 19 | 5.511 (5.484 – 5.539) | −0.041 (−0.185 – 0.103) | |||

| Sex | Female | 37 | 5.508 (5.484 – 5.532) | 0.060 (−0.054 – 0.175) | ||

| Male | 46 | 5.492 (5.476 – 5.508) | 0.126 (0.037 – 0.215) | |||

| Smoking Status | Never | 30 | 5.489 (5.226 – 5.669) | 0.080 (−0.047 – 0.206) | ||

| Occasionally | 19 | 5.508 (5.411 – 5.588) | 0.180 (−0.429 – 0.432) | |||

| Daily | 6 | 5.495 (5.458 – 5.558) | 0.002 (0.037 – 0.324) | |||

| Unknown | 28 | 5.506 (5.399 – 5.630) | 0.078 (−0.038 – 0.194) | |||

| BMI | <25 (Normal) | 33 | 5.490 (5.467 – 5.512) | 0.160 (0.061 – 0.260) | ||

| 25–29 (Overweight) | 23 | 5.507 (5.493 – 5.522) | 0.151 (0.015– 0.287) | |||

| >30 (Obese) | 22 | 5.490 (5.455 – 5.526) | −0.015 (−0.171 – 0.141) | |||

| Stunted | No | 50 | 5.500 (5.485 – 5.515) | 0.059 (−0.036 – 0.153) | ||

| Yes | 28 | 5.480 (5.457 – 5.515) | 0.180 (0.065 – 0.294) | |||

| Vegetable Consumption Daily or Weekly | Low (0 – 1) | 19 | 5.487 (5.458 – 5.515) | 0.088 (−0.053 – 0.229) | ||

| Medium | 50 | 5.499 (5.480 – 5.517) | 0.089 (−0.007 – 0.184) | |||

| High (5 – 6) | 14 | 5.518 (5.481 – 5.556) | 0.137 (−0.041 – 0.317) | |||

| Diversity of Vegetable consumption | Low (2 – 3) | 14 | 5.465 (5.226 – 5.568) | 0.026 (−0.175– 0.228) | ||

| Medium | 44 | 5.505 (5.400 – 5.669) | 0.099 (0.001 – 0.197) | |||

| High (6) | 25 | 5.483 (5.399 – 5.630) | 0.132 (0.007 – 0.257) | |||

| Fruit Consumption Daily or Weekly | Low (0 – 1) | 31 | 5.483 (5.456 – 5.510) | 0.123 (−0.033 – 0.213) | ||

| Medium | 40 | 5.512 (5.493 – 5.530) | 0.090 (−0.024 – 0.203) | |||

| High (4 – 6) | 12 | 5.499 (5.474 – 5.523) | 0.051 (−0.193 – 0.296) | |||

| Diversity of Fruit consumption | Low (5 – 6) | 17 | 5.501 (5.411 – 5.628) | 0.034 (−0.100 – 0.169) | ||

| Medium | 42 | 5.501 (5.333 – 5.630) | 0.120 (0.013– 0. 227) | |||

| High (8 – 9) | 24 | 5.496 (5.226 – 5.669) | 0.100 (−0.036– 0.235) | |||

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.0001

N/A not applicable

Differences in Log10(mtDNA CN) and mtDNA damage were evaluated using independent t-tests for variables with two categories and a chi-square test for variables with three or more categories.

Table II.

Select study population characteristics that vary by community location.

| INDIVIDUAL DATA | N | Overall | Community Location | Chi-square for difference across groups (p-value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upriver from ASGM (n=29) | Near Puerto Maldonado (n=25) | Downriver of ASGM (n=29) | |||||

| Log10 mtDNA Copy Number (mean) | 83 | 5.499 | 5.501 | 5.517 | 5.482 | 0.1305 c | |

| mtDNA Damage/10 kilobase pairs (mean) | 83 | 0.097 | 0.271 | −0.140 | 0.126 | <0.0001 c | |

| Hair Mercury (mean μg/g) | 83 | 3.49 | 3.551 | 3.727 | 3.226 | 0.982 | |

| Mercury Status (%) | <1.2 | 8 | 9.6 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 0.8121 |

| 1.2–1.9 | 14 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 4.0 | 3.5 | ||

| 2.0–5.9 | 48 | 57.8 | 51.7 | 64.0 | 75.9 | ||

| >6.0 | 13 | 15.7 | 24.1 | 28.0 | 13.8 | ||

| Smoking Status (%) | Never | 30 | 36.1 | 24.1 | 12.0 | 27.6 | 0.0980 |

| Occasionally | 19 | 22.9 | 41.4 | 8.0 | 31.0 | ||

| Daily | 6 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 20.0 | 13.8 | ||

| Unknown | 28 | 33.7 | 27.6 | 60.0 | 27.6 | ||

| % Stunted | 83 | 35.9 | 33.3 | 9.5 | 48.3 | 0.0535 | |

| BMI (%)c | <25 (Normal) | 33 | 42.3 | 44.8 | 25.0 | 48.3 | 0.3045 |

| 25–29 (Overweight) | 23 | 30.8 | 27.6 | 35.0 | 34.5 | ||

| >30 (Obese) | 22 | 26.9 | 27.6 | 40.0 | 17.2 | ||

| HOUSEHOLD DATA | (n=12) | (n=13) | (n=13) | ||||

| Diversity of Vegetable consumption (%) b | Low (2 – 3) | 4 | 23.7 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 46.2 | 0.0425 a |

| Medium | 24 | 60.5 | 66.7 | 69.2 | 46.2 | ||

| High (6) | 10 | 15.8 | 33.3 | 7.7 | 7.7 | ||

Characteristics for the study population, overall and stratified by location: three communities upriver from ASGM, near Puerto Maldonado and far downriver from ASGM, as depicted in Figure 1.

p-value computed from a Fisher’s Exact Test

High and Low categories of consumption and diversity are based on the approximate 80th and 20th percentiles of the distribution

p-value is computed from an F-test

3.2. mtDNA Copy Number

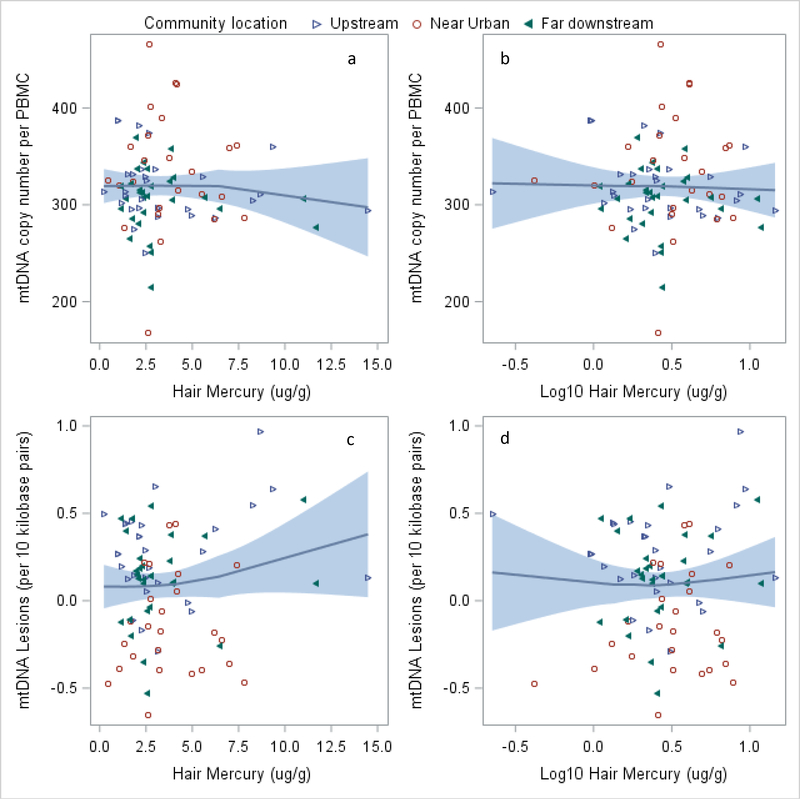

mtDNA CN in our samples varied widely, from 168 to 467 copies/cell (mean of 316 copies, standard deviation of 44.8 copies/cell), but did not vary significantly between communities or by location. Overall, mtDNA CN was not associated with total hair Hg or Hg exposure group in unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Table I, Figure 2a, 2b). There may exist variability in the relationship when stratified by location (Supplemental Figure 2), but it was not statistically significant in this analysis.

Figure 2. mtDNA Copy Number and Lesions by Total Hair Mercury (ug/g and Log10 transformed).

Panel sets A and B show the relationship between mtDNA CN/PBMC and total hair mercury and log10 total hair mercury, respectively. Panel sets C and D show the relationship mtDNA damage/10kb and total hair mercury and log10 total hair mercury, respectively. Points are distinguished by household location being upstream from ASGM (hollow blue triangles), near urban (red circles), or far downstream (filled green triangles).

No statistically significant interactions were observed between age and sex with total hair Hg or Hg exposure group (Supplemental Table III). No significant interactions were found with total hair Hg and community location or vicinity to PEM. Among all the variables tested, only frequency of vegetable consumption was associated with Log10 mtDNA CN (Table III). Individuals who ate four different vegetables either daily or weekly had a 0.9% logged increase in mtDNA CN, equivalent to an increase of 88.5 mtDNA copies. This represents a 1.01 – 1.25-fold increase in mtDNA copies compared to those with low frequency of vegetable consumption. Other health and spatial characteristics, including stunting, obesity, BMI, smoking status, community location to ASGM, and vicinity to PEM were not associated with Log10 mtDNA CN in this study.

Table III.

Model-adjusted factors associated with Log10 mtDNA Copy Number.

| VARIABLE | Log10(mtDNA CN) a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | (SE) | ||

| Log10 Total Hair Mercury (μg/g) | Log(Hg) | −0.001 | (0.024) |

| Mercury Exposure Group (REF=Low) | High(>6ug/g) | 0.004 | (0.019) |

| Smoking Status (REF=Never) | Daily | −0.0001 | (0.028) |

| Sometimes | 0.012 | (0.018) | |

| Unknown | 0.004 | (0.017) | |

| Stunted | HAZ ≤ −2 | −0.012 | (0.014) |

| Obese | BMI ≥ 30 | −0.021 | (0.018) |

| BMI (Body Mass Index) | −0.006 | (0.008) | |

| Frequency of Vegetable Consumption (REF=High) | Low | −0.050 | (0.024) † |

| Medium | −0.007 | (0.019) | |

| Diversity of Vegetable Consumption (REF=High) | Low | −0.029 | (0.027) |

| Medium | −0.021 | (0.023) | |

| Frequency of Fruit Consumption (REF=High) | Low | −0.026 | (0.026) |

| Medium | 0.008 | (0.025) | |

| Diversity of Fruit Consumption (REF=High) | Low | 0.005 | (0.024) |

| Medium | 0.007 | (0.019) | |

| <20 miles of the capital, Puerto Maldonado (PEM) | Near | 0.016 | (0.018) |

| Community Location (REF = Near Puerto) | Downriver | −0.024 | (0.020) |

| Upriver | −0.007 | (0.020) | |

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.0001

N/A not applicable

Beta and standard error estimates from a multivariate model adjusted for age and sex, with household used as a random variable.

3.3. mtDNA Damage

mtDNA damage ranged from −0.652 to 0.971 lesions/10kb and varied by location with people living upriver having the highest number of lesions followed by people living downriver from PEM (Table II). Differences in mtDNA damage by location remained significant after adjusting for age and sex (Table IV). People living upriver and downriver from PEM had 0.42 and 0.27 more lesions/10kb than those living near PEM, respectively, while people living far from PEM (>20 miles) had 0.34 more lesions/10kb compared to people living near PEM (<20 miles).

Table IV.

Model-Adjusted estimates of mtDNA damage (lesions per 10 kilobase pairs), All Locations and Locations Stratified by Vicinity to Puerto Maldonado

| VARIABLE | Overall mtDNA Damage a | Stratified Model b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Far from PEM | Near PEM | ||||||

| Beta | (SE) | Beta | (SE) | Beta | (SE) | ||

| Log10 Total Hair Mercury (μg/g) | 0.12 | (0.115) | 0.069 | (0.12) | 0.205 | (0.214) | |

| High Mercury Exposure (>6μg/g, vs. low) | 0.093 | (0.090) | 0.225 | (0.103)† | −0.071 | (0.157) | |

| Smoking Status (REF=Never) | Daily | 0.011 | (0.128) | 0.072 | (0.177) | −0.024 | (0.223) |

| Sometimes | 0.092 | (0.086) | 0.073 | (0.093) | −0.199 | (0.353) | |

| Unknown | 0.071 | (0.078) | 0.075 | (0.095) | 0.095 | (0.163) | |

| Stunted (HAZ ≤ −2) | 0.082 | (0.068) | 0.041 | (0.075) | 0.004 | (0.201) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) | −0.180 | (0.082) † | −0.040 | (0.101) | −0.312 | (0.131)† | |

| BMI (Body Mass Index) | −0.006 | (0.006) | 0.007 | (0.009) | −0.026 | (0.014)* | |

| Frequency of Vegetable Consumption (REF=High) | Low | −0.031 | (0.110) | −0.228 | (0.102)† | 0.084 | (0.253) |

| Medium | −0.005 | (0.083) | −0.062 | (0.082) | 0.059 | (0.141) | |

| Diversity of Vegetable Consumption (REF=High) | Low | 0.092 | (0.115) | 0.032 | (0.118) | −0.323 | (0.225) |

| Medium | 0.017 | (0.088) | 0.065 | (0.101) | −0.256 | (0.192) | |

| Frequency of Fruit Consumption (REF=High) | Low | 0.080 | (0.102) | 0.048 | (0.099) | −0.144 | (0.325) |

| Medium | 0.154 | (0.098) | 0.206 | (0.107)* | 0.153 | (0.245) | |

| Diversity of Fruit Consumption (REF=High) | Low | 0.017 | (0.105) | −0.101 | (0.087) | 0.015 | (0.172) |

| Medium | −0.006 | (0.082) | −0.084 | (0.087) | 0.101 | (0.159) | |

| <20 miles from Puerto Maldonado (PEM) | 0.341 | (0.094)†† | NA | NA | |||

| Community Location (REF = Near Puerto) | Downriver | 0.267 | (0.098) † | NA | NA | ||

| Upriver | 0.406 | (0.098) †† | NA | NA | |||

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.0001

N/A not applicable

Multivariate random effect model with age, sex, the listed covariate and community as the random variable.

Stratified models adjust for age and sex, but do not include a community random effect.

NA- Variables for location were not tested in the stratified model

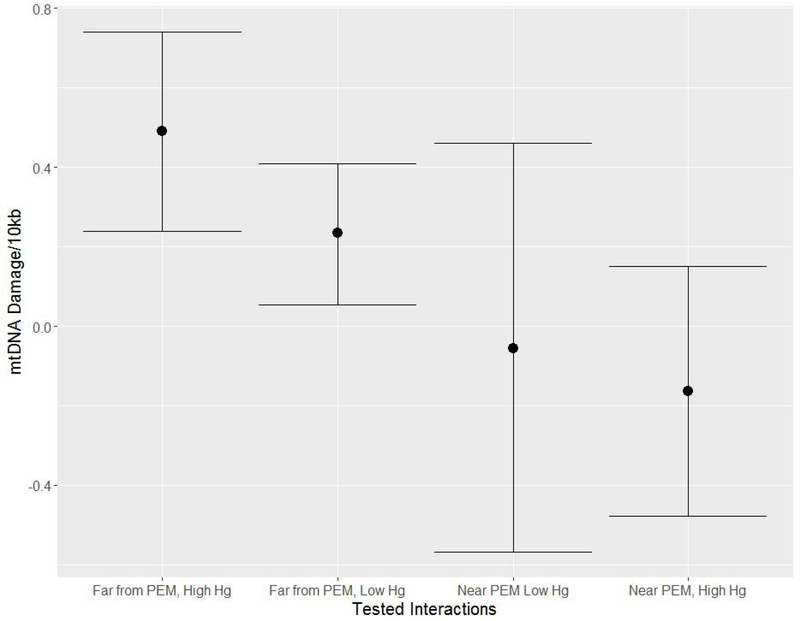

mtDNA damage increased with higher hair Hg levels (Figures 2c, 2d), but the relationship was not significant (Table IV). Interactions of the effect of Hg levels on mtDNA damage and location (near vs. far proximity to PEM) revealed that living far from PEM was associated with higher mtDNA damage, regardless of Hg exposure, than living near PEM (Figure 3, Supplemental Table IV and Supplemental Figure 2). Models stratified by community location show consistent results, with high Hg level associated with 0.225 more lesions in communities far from PEM (p=0.033; Supplemental Table IV).

Figure 3. Variable interactions for mtDNA damage (damage per 10 kilobase pairs).

Predicted lesions controlling for age and sex with an interaction between mercury exposure groups (high (>6ug/g) vs. low) and living near PEM (<20 miles). Community was used as a random variable. Black dots show the predicted damage and the black lines the 95% confidence interval.

mtDNA damage tended to decrease with increasing age (Supplemental Table IV). An age*Hg interaction indicated differential effects of age by Hg exposure with 0.55 more lesions/10kb predicted for individuals with high (vs. low) Hg levels, and high Hg exposure associated with a more rapid decline in lesions with increasing age (Supplemental Table IV, Model 2).

Among variables related to nutritional status, only obesity predicted mtDNA damage. Controlling for age and sex, being obese was associated with 0.18 fewer lesions/10kb (p<0.02) than people who were not obese (Table IV). However, analyzed as a continuous variable (BMI), the effect was not significant. Stratified by community location, the effect of obesity (and BMI) was consistent, but estimates were only significant for persons living near PEM. The interaction of sex with obesity indicated that being obese resulted in less damage in females vs. males (Supplemental Table V).

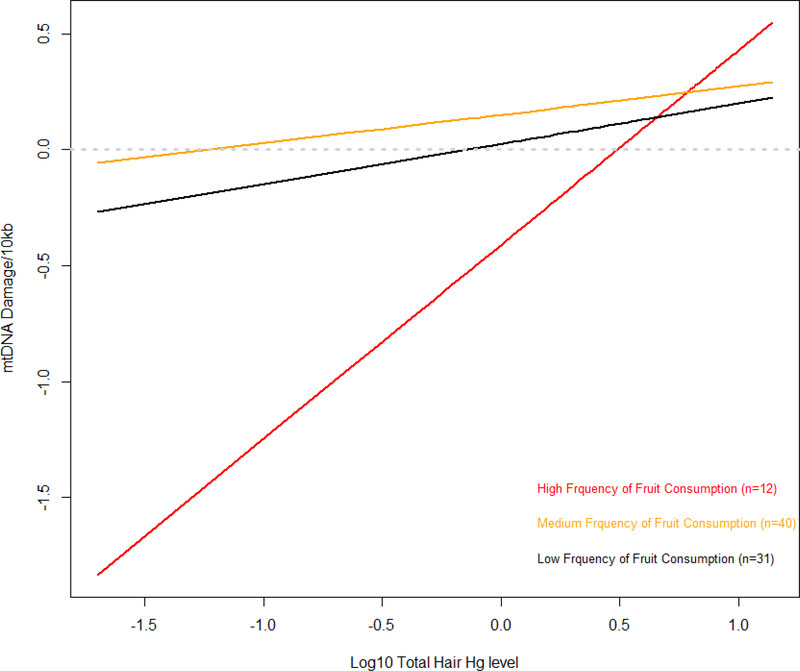

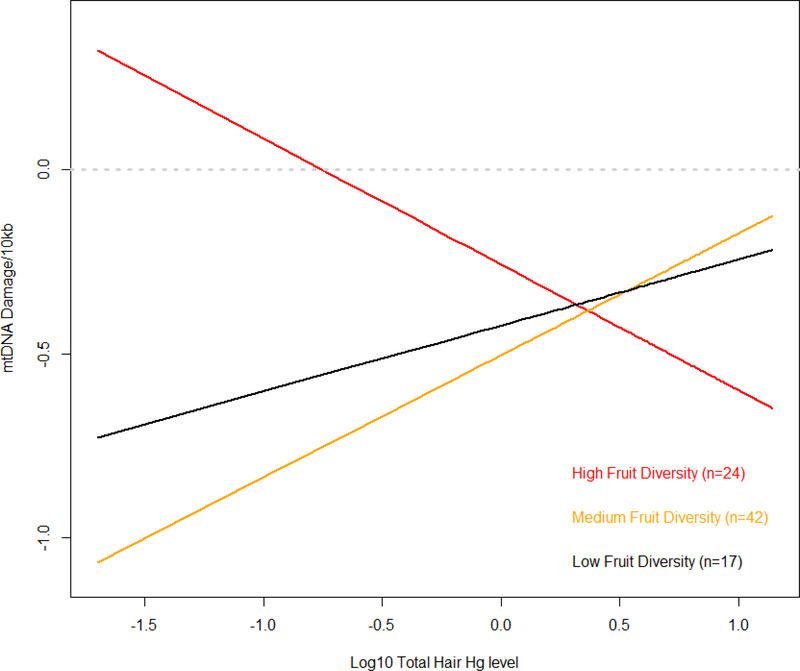

Household frequency and diversity of vegetable and fruit consumption was not associated with mtDNA damage in adjusted models (Table IV). However, we were interested in the potential for diets higher in antioxidants to influence mtDNA damage or modify the effect of Hg exposure on damage; therefore we stratified individuals by fruit consumption (frequency and diversity) to assess interactions with Hg exposure. We found that the effect of fruit frequency and diversity did modulate the effect of mercury exposure (Supplemental Table IV, models 6 and 7). The model results indicate that at low Hg exposure (the 10th percentile), those with high frequency of fruit consumption had less damage, i.e., high fruit consumption appeared was protective against mtDNA damage; however, as Hg exposure increased, significant differences in mtDNA damage between frequency of fruit consumption groups disappeared (Figure 4). In contrast, high fruit diversity resulted in greater predicted damage at low Hg exposure levels compared to low and medium fruit diversity. At higher exposure levels, high fruit diversity resulted in significantly less damage than low and medium diversity (Supplemental Table IV, Figure 5).

Figure 4. Estimated interaction effects of log10 total hair Hg and frequency of fruit consumption to predict mtDNA damage.

Log10 total hair mercury by diets low, medium and high frequency fruit consumption (red, orange, and black, respectively). Model predictions were calculated using beta values of linear mixed model estimates shown in Supplementary Table IV, model 6, which adjust for age and sex.

Figure 5. Estimated interaction effects of log10 total hair Hg and diversity of fruit consumption to predict mtDNA damage.

Log10 total hair mercury by low, medium and high fruit diversity diets (red, orange and black, respectively). Model predictions were calculated using beta values of linear mixed model estimates shown in Supplementary Table IV, model 7, which adjust for age and sex.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that in human populations, the relationship between mercury exposure at these levels and mtDNA CN and damage in WBCs is likely mediated or modified by factors such as diet, nutritional status, and residential location. We did not find a direct significant association between total hair Hg levels and mtDNA CN or mtDNA damage. Our analysis found Hg to be associated with detectable mtDNA damage only in the context of specific interactions with age, community location, and fruit consumption. While our exploratory study was not powered to test interactions, the direction of effects with significant p-values supports the need for future work.

Among other factors, our study indicates that diet, obesity and community location influenced mtDNA CN and damage. Interestingly, diet was the only factor that significantly affected both mtDNA CN and mtDNA damage. Diet modulates cellular responses to exposure to xenobiotics and heavy metals by a variety of means, including transcriptional regulation of xenobiotic metabolism, antioxidant defense, and mitochondrial homeostasis pathways. Vegetables and fruits are high in nutrients such as carotenoids, isothiocyanates and phenolic antioxidants that activate transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid-2- related factor 2 (Nrf2), which regulates over two dozen genes involved with detoxification of xenobiotics (Pall and Levine 2015); mitochondrial biogenesis and fusion (Sabouny et al. 2017); improves mitochondrial function (Pall and Levine 2015) including the removal of damaged mitochondria (Holmstrom et al. 2016); and helps improve cellular response to stress through its regulation of antioxidant genes such as heme oxygenase 1, quinone oxidoreductase and two superoxide dismutase genes (He et al. 2001; MacLeod et al. 2009; Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova 2014; Kumar et al. 2014). Nrf2 also dose-dependently activates metallothionein (Wu et al. 2011), an important protein that chelates, transports and helps eliminate heavy metals, including Hg, from the cell (Klaassen and Liu 1998; Sears 2013). Nrf2-deficient mice have significantly higher Hg accumulation in the brain than wild-type mice injected with isothiocyanates (Toyama et al. 2011). Thus, individuals with high vegetable consumption may have had significantly higher mtDNA CN compared to low vegetable consumption due to stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Similarly, those with a higher frequency of fruit consumption may have had less mtDNA damage due to increased metallothionein-mediated sequestration of Hg, increased antioxidant defenses, and increased removal of damaged mtDNAs via mitophagy. This study provides further evidence that diet is an important factor in mitochondrial health and modulates toxicity at the cellular level.

This is the first study that we are aware of to analyze obesity and mtDNA damage. We initially hypothesized that obesity would be associated with more mtDNA damage due to the general association of obesity with inflammatory responses (Recasens et al. 2004; Reilly and Saltiel 2017). Instead, interestingly, obesity was associated with significantly less mtDNA damage. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, it is possible that the emergence of obesity in Peruvian Amazon populations is distinct mechanistically from better studied developed world environments as obesity in our data is not associated with hypertension or higher levels of visceral fat as it typically has been in developed world studies (Seravalle and Grassi 2017). More succinctly, obesity in remote areas of the Amazon likely originates from excess carbohydrate consumption, compared to the western contexts in which obesity arises from a diet high in processed sugars and fats. Compared to carbohydrates, processed sugars are absorbed into the body much more rapidly causing spikes in sugar levels, while carbohydrates provide a more stable energy source. These differences in etiology of dietary obesity could have different impacts on mtDNA health.

Second, obesity may result in protection of mitochondria despite a potentially inflammatory environment. Adipose tissue is involved in inflammation and immune responses as it releases cell signaling proteins such as leptin and adiponectin. In the human body, leptin helps regulate white blood cells and is associated with an effective immune response (Ozata et al. 1999). Leptin concentrations in serum have been shown to increase with BMI (Considine et al. 1996; Zarrati et al. 2017), and leptin concentrations are higher in women than in men with the same body fat (Casabiell et al. 1998), which is consistent with our findings that obese women had less mtDNA damage than obese men. In some tissues (e.g., skeletal muscle, although not others, e.g. hypothalamus) leptin can activate AMP Kinase, which activates mitochondrial biogenesis as well as degradation, potentially speeding the rate of replacement of old mitochondria with new and reducing steady-state mtDNA damage.

Smoking was not a statistically significant factor for either mtDNA CN or damage, which was unexpected based on previous studies (Ballinger et al. 1996; Cakir et al. 2007; Fetterman et al. 2013). However, the lack of significance is likely due to high non-response from individuals (34%) and the low number of people who considered themselves smokers. Overall, smoking in the region is not common, especially in smaller communities outside the vicinity of PEM.

We were also surprised that there was not a stronger association of age and mtDNA CN or damage, given previous research that found lower mtDNA CN in people over 60 years of age (Shen et al. 2015). However, unlike previous studies (Shen et al. 2015), only 5% of our study population was over 60, possibly preventing statistical differentiation. It is also possible that elderly people in this region live more active, physical lives than elderly in developed countries, thus, their average muscle loss or other factors related to mtDNA damage may be similar to someone younger living in a developed country.

The lack of a direct impact of Hg exposure on mtDNA CN or damage is the first report of effect or lack thereof in a human population. It is important to note that the potential for interactive effects with genotoxicants (as has been observed in laboratory models: Wyatt et al., 2017) or with dietary limitations (as in the current study) remains important. The average lesion values for some groups in this study are in the range of 0.4–0.6 lesions/10 kb, compared to previously reported values of 0.75/10 kb for patients with Friedreich’s ataxia (Haugen et al. 2010), and 0.17/10 kb for veterans with Gulf War Illness (Chen et al. 2017). We also note that since most Hg in circulating blood is associated with the hemoglobin of red blood cells and plasma (Berglund et al. 2005), rather than white blood cells, WBCs may serve as a poor proxy for potential effects of Hg on target tissues such as the nervous and immune systems.

There are other limitations of the study. The study is unable to account for potential disease states such as cancer (Lan et al. 2008; Hosgood et al. 2010; Hosnijeh et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2015; Tin et al. 2016) or the effects of other xenobiotics, including pharmaceuticals that may impact mtDNA (Dykens et al. 2007; Cohen 2010; Meyer et al. 2013). This study also did not account for inter-individual differences in relative proportions of white blood cells in blood samples and cannot account for any fluctuations of individuals who may have had higher levels of white blood cells due to injury or infection. Blood samples were collected in the summer when diseases such as the common cold and arboviruses are less common, reducing the probability of such hematocrit fluctuations. Finally, we do not have measures of internal mercury concentrations in the WBCs, or in the cells of the laboratory studies which reported Hg-induced mtDNA damage, so we cannot exclude the possibility that the lack of effect in this case is attributable to a lower level of exposure.

In addition, the study is limited in its ability to distinguish long-term and acute Hg exposure as hair measurements represent a time-integrated measurement corresponding to roughly two months prior to collection. Hair samples from this region were demonstrated to be predictive of chronic exposure(Wyatt et al. 2017a); however, acute Hg exposure is likely exclusive to gold miners, which constitute just two study participants. The half-life of MeHg in blood is approximately two months, which is well reflected in our study, since it is approximately the time captured in the hair samples that we obtained (Smith and Farris 1996; Yaginuma-Sakurai et al. 2012). Whole blood includes many mitochondria-containing cells, including T cells, B cells, granulocytes, monocytes, and platelets, each with different half-lives, ranging from hours to months. This raises the question of whether MeHg exposure will vary across cell type, which to our knowledge is unknown. Future studies should examine Hg levels as well as mtDNA parameters in specific WBC cell types.

This study is the first to attempt to translate mtDNA CN and damage as biomarkers of Hg exposure in a human population. Here, we report compelling effects of non-toxicant variables on mtDNA endpoints, as well as the potential for combinatorial effects of exposure to multiple stressors, including diet and Hg. Importantly, we did not replicate prior experimental results showing direct relationships between Hg and mtDNA endpoints. Hg, although capable of causing mtDNA damage in the laboratory, was much less associated with mtDNA damage than other factors examined in this human study. We highlight this negative result to emphasize the importance of empirical confirmation of translational impact of experimental (laboratory) environmental toxicology. We also highlight that in some cases (the effects of obesity and age on mtDNA), our results were unexected based on previous epidemiological results, perhaps due to differences betewen developing and developed world contexts. Perhaps most compellingly, most of the observed variability in mtDA endpoints was not explained by any tested variables; it is interesting that this was true as well in the wild bat study (Karouna-Renier et al. 2014). Therefore,we have yet to account for important variables that regulate mtDNA homeostasis; despite decades of laboratory research into determinants of mtDNA homeostasis as a communiy, we have yet to fully identify the key factors. Population health is complex, and effective and interpretable biomarkers of exposure and effect must be field tested for robustness to this complexity. Most translational work tends to be from “bench to bedsite/community”; our results emphasize a critical need for bidirectional, mutually informed translational research to develop efective environmental health biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Yerko Rios Mardini, Reyna Gutierrez, Jovana Chuchillo Salas, and Lorenza Andrade for support in data collection. We are grateful for the participation of the families enrolled in this study. We acknowledge the local health directorate (Direccion Regional de Salud de Madre de Dios), the Peruvian Navy, the US Naval Medical Research Unit (NAMRU-6), and the Asociacion para la Conservacion de la Cuenca Amazonica (ACCA) for providing logistical support for the project. This research was funded through internal grants at Duke University (Duke Global Health Insistute, Pratt School of Engineering, Bass Connections Program, Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies) and external support from the InterAmerican Instistute (IAI) for Global Change Research [CRN3036 to WP] and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) [P42ES010356 to JNM and HHK, and 1R21ES026960 to WP]. No funding agency had any participation in the design, analysis or interpretation of data for this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the IAI or NIEHS.

Abbreviations

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- CN

copy number

- ASGM

artisanal and small-scale gold mining

- WBC

white blood cell

References

- Akagi H, Malm O, Branches FJP, Kinjo Y, Kashima Y, Guimaraes JRD, Oliveira RB, Haraguchi K, Pfeiffer WC, Takizawa Y, Kato H. 1995. Human exposure to mercury due to goldmining in the Tapajos River basin, Amazon, Brazil: Speciation of mercury in human hair, blood and urine. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 80(1):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alexeyev M, Shokolenko I, Wilson G, LeDoux S. 2013. The maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity--critical analysis and update. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5(5):a012641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim MI, Mergler D, Bahia MO, Dubeau H, Miranda D, Lebel J, Burbano RR, Lucotte M. 2000. Cytogenetic damage related to low levels of methyl mercury contamination in the Brazilian Amazon. An Acad Bras Cienc 72(4):497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Syversen T. 2005. Methylmercury: recent advances in the understanding of its neurotoxicity. Ther Drug Monit 27(3):278–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison WD, Hare MF. 1994. Mechanisms of methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity. Faseb j 8(9):622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR AfTSaDR. 1999. Toxicological Profile for Mercury. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger SW, Bouder TG, Davis GS, Judice SA, Nicklas JA, Albertini RJ. 1996. Mitochondrial genome damage associated with cigarette smoking. Cancer Res 56(24):5692–5697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos GRM, Grotto D, Serpeloni JM, Aissa AF, Antunes LMG, Knasmüller S, Barbosa F. 2012. Bixin and norbixin protect against DNA-damage and alterations of redox status induced by methylmercury exposure in vivo. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis 53(7):535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund M, Lind B, Björnberg KA, Palm B, Einarsson Ö, Vahter M. 2005. Inter-individual variations of human mercury exposure biomarkers: a cross-sectional assessment. Environmental Health 4(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bess AS, Ryde IT, Hinton DE, Meyer JN. 2013. UVC-induced mitochondrial degradation via autophagy correlates with mtDNA damage removal in primary human fibroblasts. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology 27(1):28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunst KJ, Baccarelli AA, Wright RJ. 2015. Integrating mitochondriomics in children’s environmental health. Journal of Applied Toxicology 35(9):976–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucio L, García C, Souza V, Hernández E, González C, Betancourt M, Gutiérrez-Ruiz MC. 1999. Uptake, cellular distribution and DNA damage produced by mercuric chloride in a human fetal hepatic cell line. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 423(1–2):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakir Y, Yang Z, Knight CA, Pompilius M, Westbrook D, Bailey SM, Pinkerton KE, Ballinger SW. 2007. Effect of alcohol and tobacco smoke on mtDNA damage and atherogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med 43(9):1279–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carocci A, Rovito N, Sinicropi MS, Genchi G. 2014. Mercury toxicity and neurodegenerative effects. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 229:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabiell X, Pineiro V, Peino R, Lage M, Camina J, Gallego R, Vallejo LG, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF. 1998. Gender differences in both spontaneous and stimulated leptin secretion by human omental adipose tissue in vitro: dexamethasone and estradiol stimulate leptin release in women, but not in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83(6):2149–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernichiari E, Myers GJ, Ballatori N, Zareba G, Vyas J, Clarkson T. 2007. The biological monitoring of prenatal exposure to methylmercury. NeuroToxicology 28(5):1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Meyer JN, Hill HZ, Lange G, Condon MR, Klein JC, Ndirangu D, Falvo MJ. 2017. Role of mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War Illness. PLoS One 12(9):e0184832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BH. 2010. Pharmacologic effects on mitochondrial function. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 16(2):189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, et al. 1996. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 334(5):292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Lopez ME, Macedo GL, Pereira SI, Arrifano GP, Picanco-Diniz DL, do Nascimento JL, Herculano AM. 2009. Mercury and human genotoxicity: critical considerations and possible molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol Res 60(4):212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S, Davidzon G. 2005. Mitochondrial DNA and disease. Annals of Medicine 37(3):222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diringer SE, Feingold BJ, Ortiz EJ, Gallis JA, Araujo-Flores JM, Berky A, Pan WKY, Hsu-Kim H. 2015. River transport of mercury from artisanal and small-scale gold mining and risks for dietary mercury exposure in Madre de Dios, Peru. Environmental Science-Processes & Impacts 17(2):478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens JA, Marroquin LD, Will Y. 2007. Strategies to reduce late-stage drug attrition due to mitochondrial toxicity. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 7(2):161–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold B, Abuawad A, Pettigrew S, Saxton A, Ortiz E, Berky A, Pan WK. 2016. Measuring the Nutritional Transition in Madre de Dios Peru. International Society for Environmental Epidemiology; Research Triangle Park, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman JL, Pompilius M, Westbrook DG, Uyeminami D, Brown J, Pinkerton KE, Ballinger SW. 2013. Developmental Exposure to Second-Hand Smoke Increases Adult Atherogenesis and Alters Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Deletions in apoE−/− Mice. PLOS ONE 8(6):e66835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi E, Loprieno G, Ballardin M, Petrozzi L, Migliore L. 1994. Cytogenetic monitoring of fishermen with environmental mercury exposure. Mutat Res 320(1–2):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Hunt CP, Rooney JP, Ryde IT, Anbalagan C, Joglekar R, Meyer JN. 2016. PCR-Based Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number, Mitochondrial DNA Damage, and Nuclear DNA Damage. Curr Protoc Toxicol 67:20.11.21–20.11.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F. 1998. Cognitive performance of children prenatally exposed to “safe” levels of methylmercury. Environ Res 77(2):165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group HCMIT. 2004. Mercury: Your Health and the Environment: A Resource Tool. p 1–54.

- Hastings FL, Lucier GW, Klein R. 1975. Methylmercury-cholinesterase interactions in rats. Environ Health Perspect 12:127–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen AC, Di Prospero NA, Parker JS, Fannin RD, Chou J, Meyer JN, Halweg C, Collins JB, Durr A, Fischbeck K, Van Houten B. 2010. Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich’s Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology. PLOS Genetics 6(1):e1000812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT. 2014. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 39(4):199–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CH, Gong P, Hu B, Stewart D, Choi ME, Choi AM, Alam J. 2001. Identification of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) as an Nrf2-interacting protein. Implication for heme oxygenase-1 gene regulation. J Biol Chem 276(24):20858–20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrom KM, Kostov RV, Dinkova-Kostova AT. 2016. The multifaceted role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Curr Opin Toxicol 1:80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosgood HD 3rd, Liu CS, Rothman N, Weinstein SJ, Bonner MR, Shen M, Lim U, Virtamo J, Cheng WL, Albanes D, Lan Q. 2010. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and lung cancer risk in a prospective cohort study. Carcinogenesis 31(5):847–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosnijeh FS, Lan Q, Rothman N, San Liu C, Cheng WL, Nieters A, Guldberg P, Tjonneland A, Campa D, Martino A, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Krogh V, Tumino R, Panico S, Masala G, Weiderpass E, Huerta Castano JM, Ardanaz E, Sala N, Dorronsoro M, Quiros JR, Sanchez MJ, Melin B, Johansson AS, Malm J, Borgquist S, Peeters PH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Wareham N, Khaw KT, Travis RC, Brennan P, Siddiq A, Riboli E, Vineis P, Vermeulen R. 2014. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and future risk of B-cell lymphoma in a nested case-control study in the prospective EPIC cohort. Blood 124(4):530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Zhu Z-Z, Zhang X, Nordio F, Bonzini M, Schwartz J, Hoxha M, Dioni L, Marinelli B, Pegoraro V, Apostoli P, Bertazzi PA, Baccarelli A. 2010. Airborne particulate matter and mitochondrial damage: a cross-sectional study. Environmental Health 9(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou LF, Zhang X, Dioni L, Barretta F, Dou C, Zheng YN, Hoxha M, Bertazzi PA, Schwartz J, Wu SS, Wang S, Baccarelli AA. 2013. Inhalable particulate matter and mitochondrial DNA copy number in highly exposed individuals in Beijing, China: a repeated-measure study. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karouna-Renier NK, White C, Perkins CR, Schmerfeld JJ, Yates D. 2014. Assessment of mitochondrial DNA damage in little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) collected near a mercury-contaminated river. Ecotoxicology 23(8):1419–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Liu J. 1998. Induction of metallothionein as an adaptive mechanism affecting the magnitude and progression of toxicological injury. Environ Health Perspect 106 Suppl 1:297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Kim IS, More SV, Kim BW, Choi DK. 2014. Natural product-derived pharmacological modulators of Nrf2/ARE pathway for chronic diseases. Nat Prod Rep 31(1):109–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung MP, Kostyniak P, Olson J, Malone M, Roth JA. 1987. Studies of the in vitro effect of methylmercury chloride on rat brain neurotransmitter enzymes. J Appl Toxicol 7(2):119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, Lim U, Liu CS, Weinstein SJ, Chanock S, Bonner MR, Virtamo J, Albanes D, Rothman N. 2008. A prospective study of mitochondrial DNA copy number and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 112(10):4247–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AK, McMahon M, Plummer SM, Higgins LG, Penning TM, Igarashi K, Hayes JD. 2009. Characterization of the cancer chemopreventive NRF2-dependent gene battery in human keratinocytes: demonstration that the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway, and not the BACH1-NRF2 pathway, controls cytoprotection against electrophiles as well as redox-cycling compounds. Carcinogenesis 30(9):1571–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez TN, Greenamyre JT. 2012. Toxin Models of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 16(9):920–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JN, Hartman JH, Mello DF. 2018. Mitochondrial Toxicity. Toxicological Sciences 162(1):15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JN, Leung MC, Rooney JP, Sendoel A, Hengartner MO, Kisby GE, Bess AS. 2013. Mitochondria as a target of environmental toxicants. Toxicol Sci 134(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JN, Leuthner TC, Luz AL. 2017. Mitochondrial fusion, fission, and mitochondrial toxicity. Toxicology 391:42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohmood I, Mieiro CL, Coelho JP, Anjum NA, Ahmad I, Pereira E, Duarte AC, Pacheco M. 2012. Mercury-induced chromosomal damage in wild fish (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) reflecting aquatic contamination in contrasting seasons. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 63(4):554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozata M, Ozdemir IC, Licinio J. 1999. Human leptin deficiency caused by a missense mutation: multiple endocrine defects, decreased sympathetic tone, and immune system dysfunction indicate new targets for leptin action, greater central than peripheral resistance to the effects of leptin, and spontaneous correction of leptin-mediated defects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84(10):3686–3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pall ML, Levine S. 2015. Nrf2, a master regulator of detoxification and also antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and other cytoprotective mechanisms, is raised by health promoting factors. Sheng Li Xue Bao 67(1):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper I, Wehe CA, Bornhorst J, Ebert F, Leffers L, Holtkamp M, Hoseler P, Weber T, Mangerich A, Burkle A, Karst U, Schwerdtle T. 2014. Mechanisms of Hg species induced toxicity in cultured human astrocytes: genotoxicity and DNA-damage response. Metallomics 6(3):662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti M, Forrow SM, Souhami RL, D’Incalci M, Hartley JA. 1991. Measurement of the sequence specificity of covalent DNA modification by antineoplastic agents using Taq DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Research 19(11):2929–2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recasens M, Ricart W, Fernandez-Real JM. 2004. [Obesity and inflammation]. Rev Med Univ Navarra 48(2):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly SM, Saltiel AR. 2017. Adapting to obesity with adipose tissue inflammation. Nat Rev Endocrinol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha JB, Freitas AJ, Marques MB, Pereira ME, Emanuelli T, Souza DO. 1993. Effects of methylmercury exposure during the second stage of rapid postnatal brain growth on negative geotaxis and on delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase of suckling rats. Braz J Med Biol Res 26(10):1077–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabouny R, Fraunberger E, Geoffrion M, Ng AC, Baird SD, Screaton RA, Milne R, McBride HM, Shutt TE. 2017. The Keap1-Nrf2 Stress Response Pathway Promotes Mitochondrial Hyperfusion Through Degradation of the Mitochondrial Fission Protein Drp1. Antioxid Redox Signal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon-Mulanovich G, Blazes DL, Lescano AG, Bausch DG, Montgomery JM, Pan WK. 2015. Economic Burden of Dengue Virus Infection at the Household Level Among Residents of Puerto Maldonado, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg 93(4):684–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JF, Carnero AM, Rivera E, Rosales LA, Baldeviano GC, Asencios JL, Edgel KA, Vinetz JM, Lescano AG. 2017. Unstable Malaria Transmission in the Southern Peruvian Amazon and Its Association with Gold Mining, Madre de Dios, 2001–2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg 96(2):304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LH, Howlett EH, McCoy J, Greenamyre JT. 2014a. Mitochondrial DNA damage as a peripheral biomarker for mitochondrial toxin exposure in rats. Toxicol Sci 142(2):395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LH, McCoy J, Hu X, Mastroberardino PG, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ, Chu CT, Van Houten B, Greenamyre JT. 2014b. Mitochondrial DNA damage: molecular marker of vulnerable nigral neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 70:214–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibye-Knudsen M, Fang EF, Croteau DL, Wilson DM 3rd, Bohr VA. 2015. Protecting the mitochondrial powerhouse. Trends Cell Biol 25(3):158–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears ME. 2013. Chelation: harnessing and enhancing heavy metal detoxification--a review. ScientificWorldJournal 2013:219840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seravalle G, Grassi G. 2017. Obesity and hypertension. Pharmacol Res 122:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Gopalakrishnan V, Lee JE, Fang S, Zhao H. 2015. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood and melanoma risk. PLoS One 10(6):e0131649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenker BJ, Pankoski L, Zekavat A, Shapiro IM. 2002. Mercury-Induced Apoptosis in Human Lymphocytes: Caspase Activation Is Linked to Redox Status. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 4(3):379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Farris FF. 1996. Methyl mercury pharmacokinetics in man: a reevaluation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 137(2):245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. 1995. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic Biol Med 18(2):321–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D, Goerlitz DS, Dumitrescu RG, Han D, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch F, Spernak SM, Orden RA, Chen J, Goldman R, Shields PG. 2008. Associations between cigarette smoking and mitochondrial DNA abnormalities in buccal cells. Carcinogenesis 29(6):1170–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tin A, Grams ME, Ashar FN, Lane JA, Rosenberg AZ, Grove ML, Boerwinkle E, Selvin E, Coresh J, Pankratz N, Arking DE. 2016. Association between Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Peripheral Blood and Incident CKD in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 27(8):2467–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toimela T, Tähti H. 2004. Mitochondrial viability and apoptosis induced by aluminum, mercuric mercury and methylmercury in cell lines of neural origin. Archives of Toxicology 78(10):565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama T, Shinkai Y, Yasutake A, Uchida K, Yamamoto M, Kumagai Y. 2011. Isothiocyanates reduce mercury accumulation via an Nrf2-dependent mechanism during exposure of mice to methylmercury. Environ Health Perspect 119(8):1117–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhouse C, Ortiz EJ, Berky AJ, Bullins P, Hare-Grogg J, Rogers L, Morales A-M, Hsu-Kim H, Pan WK. 2017. Hair Mercury Level is Associated with Anemia and Micronutrient Status in Children Living Near Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene:−. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KC, Cui JY, Klaassen CD. 2011. Beneficial role of Nrf2 in regulating NADPH generation and consumption. Toxicol Sci 123(2):590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt L, Ortiz E, Feingold B, Berky A, Diringer S, Morales A, Jurado E, Hsu-Kim H, Pan W. 2017a. Spatial, Temporal, and Dietary Variables Associated with Elevated Mercury Exposure in Peruvian Riverine Communities Upstream and Downstream of Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(12):1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt LH, Diringer SE, Rogers LA, Hsu-Kim H, Pan WK, Meyer JN. 2016. Antagonistic Growth Effects of Mercury and Selenium in Caenorhabditis elegans Are Chemical-Species-Dependent and Do Not Depend on Internal Hg/Se Ratios. Environ Sci Technol 50(6):3256–3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt LH, Luz AL, Cao X, Maurer LL, Blawas AM, Aballay A, Pan WK, Meyer JN. 2017b. Effects of methyl and inorganic mercury exposure on genome homeostasis and mitochondrial function in Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Repair (Amst) 52:31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaginuma-Sakurai K, Murata K, Iwai-Shimada M, Nakai K, Kurokawa N, Tatsuta N, Satoh H. 2012. Hair-to-blood ratio and biological half-life of mercury: experimental study of methylmercury exposure through fish consumption in humans. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences 37(1):123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrati M, Salehi E, Razmpoosh E, Shoormasti RS, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Shidfar F. 2017. Relationship between leptin concentration and body fat with peripheral blood mononuclear cells cytokines among obese and overweight adults. Ir J Med Sci 186(1):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Cayir A, Trevisi L, Sanchez-Guerra M, Lin X, Peng C, Bind MA, Prada D, Laue H, Brennan KJ, Dereix A, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Schwartz J, Baccarelli AA. 2016. Traffic-Related Air Pollution, Blood Pressure, and Adaptive Response of Mitochondrial Abundance. Circulation 133(4):378–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.