Fisher et al. (1) investigate the congruence between intraindividual correlations and cross-sectional correlations using six empirical datasets. While others have emphasized that there is no mathematical law dictating that these correlations should be the same (2–4), empirical studies are imperative to determine whether or not they differ in practice. Therefore, we greatly appreciate this timely and valuable contribution.

However, Fisher et al. (1) also raise a concern regarding the variability in correlations, which we believe is ill informed. Specifically, they state, “the variance around the expected value was two to four times larger within individuals than within groups. This suggests that literatures in social and medical sciences may overestimate the accuracy of aggregated statistical estimates.” We argue that this comparison is fundamentally flawed, because the two variances they compare are designed to represent inherently different phenomena.

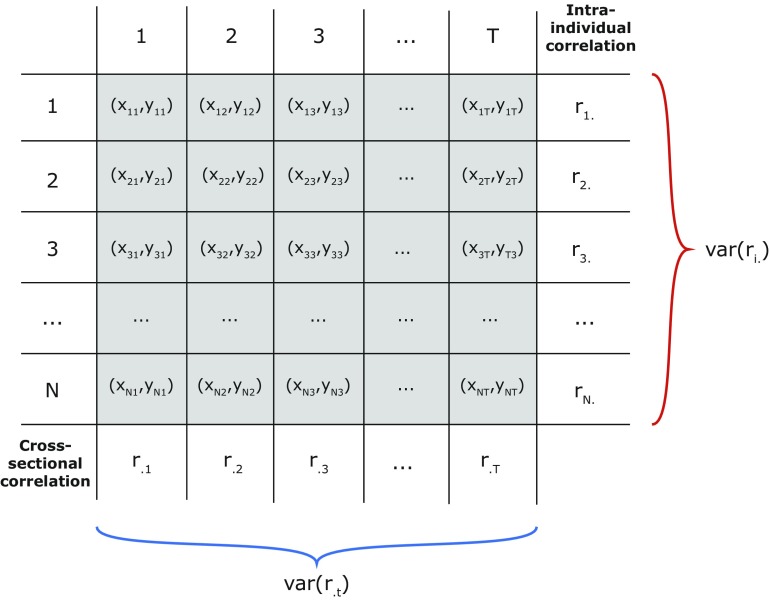

The first variance they consider is based on estimating a correlation per person (over time), and then taking the variance of this intraindividual correlation across persons (right-hand margin in Fig. 1). This variance can be considered an estimate of a random effect, representing true individual differences in the intraindividual correlation.

Fig. 1.

Each cell in the data matrix contains a bivariate observation for person i at occasion t, with i = 1, …, N and t = 1, …, T. The right-hand margin contains intraindividual correlations per person, ri.. The variance of this consists of (i) the variance of the true intraindividual correlations, ρi. (i.e., random effect), and (ii) the variance of sampling error, ri.−ρi.. The latter goes to zero as the number of occasions, T, increases. The bottom margin contains the cross-sectional correlation estimates per occasion, r.t. Under the assumption of stationarity (ρ.t = ρ..), the variance of this consists of sampling error variance only and will go to zero as the number of individuals, N, increases.

The second variance they consider is based on estimating the correlation per occasion (over persons), and then computing the variance of this cross-sectional correlation across occasions (bottom margin in Fig. 1). This latter variance can be thought of as a proxy of the squared SE of the cross-sectional correlation estimate. To see this, recall that a SE reflects the variability in parameter estimates when drawing independent samples of the same size, from the same population, infinitely many times (5). Hence, even though the samples used here are not independent (i.e., they consist of the same individuals at different occasions), the second variance the authors compute is clearly based on the same logic that underlies the squared SE of the cross-sectional correlation estimate.

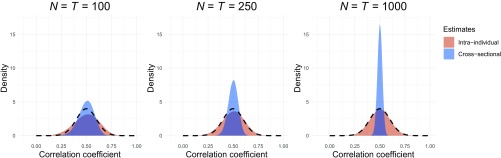

Two comments can thus be made about comparing these variances. First, a SE is not supposed to measure variability across individuals; rather, it is a measure of variability in the parameter estimate from sample to sample. Second, the SE of a correlation estimate is a function of the correlation and the sample size (6) and will go toward zero as the number of individuals increases; in contrast, the variability of the intraindividual correlation is a function of both sampling variance (which will go to zero as the number of time points increases) and the random effect (which is independent of the number of individuals and time points, see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The effect of sample size (number of persons, N, and number of time points, T) on the distributions of (i) intraindividual correlation estimates, ri. (pink), and (ii) cross-sectional correlation estimates, r.t (blue). For simplicity, the cross-sectional correlation and the average within-person correlation are both 0.5; the dashed density represents the random effect (i.e., true individual differences in intraindividual correlation). As sample size increases, sampling variance goes to 0 so that (i) the pink distribution coincides with the true dashed density, and (ii) the blue distribution becomes increasingly narrow. The var(ri.)/var(r.t) ratio changes from 2.62 to 5.21 to 17.

To be clear, the authors emphasize that the two variances they compare are not the same. However, we argue that this is not surprising at all: A squared SE is not an estimate of a random effect and should not be interpreted as meaning to reflect such. Hence, the take-home message is not that we may be overestimating the accuracy of aggregated statistical estimates, but that we should interpret measures in terms of what they are meant to represent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO; Onderzoekstalent Grant 406-15-128).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fisher AJ, Medaglia JD, Jeronimus BF. Lack of group-to-individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E6106–E6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711978115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamaker EL. Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life. Guilford Press; New York: 2012. pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molenaar PCM. A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement. 2004;2:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz B. Auf der Suche nach dem verlorenen Individuum: Vier Theoreme zur Aggregation von Prozessen. Psychol Rundsch. 2000;51:83–92. German. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everitt BS, Skrondal A. The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics. 4th Ed Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowley AL. The standard deviation of the correlation coefficient. J Am Stat Assoc. 1928;23:31–34. [Google Scholar]