Significance

Disorders of endometrial epithelial regeneration result in severe pathological conditions, including uterine cancer, endometriosis, and infertility. The lack of a detailed understanding of the cellular mechanisms underlying endometrial epithelial regeneration during the mouse estrous cycle or human menstrual cycle hinders the effective treatment of such diseases. Here, I demonstrate that the mouse uterine endometrial epithelium is maintained by a resident tissue stem cell population. These stem cells survive cyclical uterine tissue loss and persistently generate all endometrial epithelial lineages during a female’s reproductive lifespan. Such findings in mice should facilitate the study of human uterine stem cells and regeneration, which will further the understanding of uterine physiology and pathology.

Keywords: mouse, uterine regeneration, epithelial stem cells, bipotent, intersection zone

Abstract

The endometrial epithelium of the uterus regenerates periodically. The cellular source of newly regenerated endometrial epithelia during a mouse estrous cycle or a human menstrual cycle is presently unknown. Here, I have used single-cell lineage tracing in the whole mouse uterus to demonstrate that epithelial stem cells exist in the mouse uterus. These uterine epithelial stem cells provide a resident cellular supply that fuels endometrial epithelial regeneration. They are able to survive cyclical uterine tissue loss and persistently generate all endometrial epithelial lineages, including the functionally distinct luminal and glandular epithelia, to maintain uterine cycling. The uterine epithelial stem cell population also supports the regeneration of uterine endometrial epithelium post parturition. The 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine pulse-chase experiments further reveal that this stem cell population may reside in the intersection zone between luminal and glandular epithelial compartments. This tissue distribution allows these bipotent uterine epithelial stem cells to bidirectionally differentiate to maintain homeostasis and regeneration of mouse endometrial epithelium under physiological conditions. Thus, uterine function over the reproductive lifespan of a mouse relies on stem cell-maintained rhythmic endometrial regeneration.

The endometrial epithelium of the uterus is composed of luminal (LE) and glandular epithelia (GE). It experiences cyclical regression and regeneration under the regulation of ovarian steroid hormones. Women go through ∼400–500 uterine menstrual cycles during their reproductive lifespan, and the endometrium thickens by ∼7 mm within 1 wk over each menstrual cycle (∼28 d) (1). In mice, endometrial epithelial cell numbers increase approximately ninefold during a 5-d-long estrous cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Periodic uterine regeneration maintains female reproductive function and general health. Disorders of endometrial epithelial proliferation lead to a range of uterine pathological conditions, including infertility, endometriosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer (2).

Adult stem cells have long been proposed to regenerate the uterus (3). Efforts to identify them in human and mouse uteri have utilized characteristics associated with limited stem or progenitor cell populations such as label retaining (4–6) and side population (SP) (7). As cells, like certain stem cells, divide infrequently, they may consistently retain DNA labels (label retaining). Such label-retaining cells have been found in multiple tissues; yet only 0.5% of all 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) label-retaining hematopoietic cells were identified as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (8). Lgr5-labeled small intestinal stem cells are distinct from “DNA label-retaining +4 intestinal progenitor cells” (9). SP cells, which efflux Hoechst dye via the ATP-binding cassette family of transporter proteins, have also been claimed as potential stem or progenitor cells in certain tissues, but SP cell properties are also shared by differentiated cells in adult tissues (10). Thus, neither label retaining nor dye efflux is a common or unique property of all stem cell populations. Nor is it clear whether such phenotypic characteristics would be seen in uterine stem cells. In vitro clonogenicity assays and transplantation have also been applied to search for potential uterine stem cells (2, 11–13), but evidence is lacking that the in vivo counterparts of these candidate cells behave like stem or progenitor cells. Mapping of the fate determination of these claimed stem or progenitor cell candidates during normal uterine cycling is required to define their stem cell potential. Thus, the existence, identity, and roles of the proposed uterine stem cells remain unknown.

Here, I have established a CreERT2-LoxP–based single-cell lineage tracing system to functionally identify stem cells in the adult mouse uterus by characterizing stem cell clones. This method utilizes a universal hallmark of stem cells, the ability to divide indefinitely (self-renewal) (9, 14–19), instead of relying on the assumed characteristics of certain stem or progenitor cell populations (4–7). In lineage tracing, a single cell is marked such that the mark is transmitted to the cell’s progeny, resulting in a labeled clone. Based on the properties of the labeled clone, it can be determined whether or not the labeled clone is a stem cell clone; accordingly, its founder cell can be identified as stem cell or not (19). Lineage tracing is a powerful and reliable tool for identifying stem cells, which has been used to discover and research adult stem cells in mouse intestine (9), epidermis (15), muscle (16), liver (17), and Drosophila ovary (18) and gut (14). The lineage mark does not change the properties of the marked cell, or its progeny, or the surrounding environment (20). Thus, lineage tracing reflects a cell’s physiological behavior and fate in the context of the intact tissue where it lives, as opposed to what it is able to do in nonniche environments, such as in vitro clonogenicity assays or transplantation. The other advantage of single-cell lineage tracing is that it can be performed in any cell type without knowing the specific gene markers of this cell type (20).

The single epithelial cell lineage tracing system in whole mouse uterus developed here faithfully tracks the behavior and fate of individual epithelial cells over normal uterine regeneration. A cell population located in the intersection zone between luminal and glandular epithelial compartments was identified that survived the repeated uterine tissue loss and persistently generated the whole endometrial epithelial lineage, including LE and GE, for the murine reproductive lifespan. This cell population is bipotent and cycles slowly, and the multicellular clones derived from it possess all of the properties of stem cell clones. Thus, these cells represent the mouse uterine epithelial stem cell population, demonstrating that resident stem cells exist in the mouse uterus to support homeostasis and cyclical regeneration of endometrial epithelium under physiological conditions.

Results

Characterization of Mouse Uterine Endometrial Epithelium.

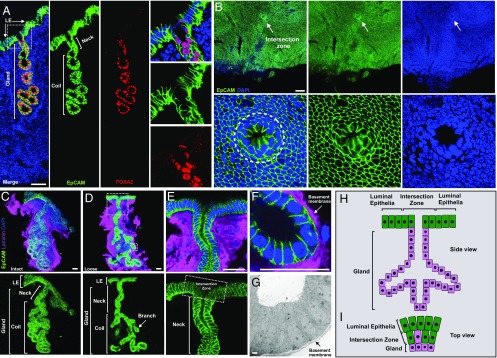

In mice, luminal epithelia and glands surrounded by stromal matrix compose the uterine endometrial epithelium (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Both epithelial compartments undergo substantial proliferation and differentiation over a uterine estrous cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Based on vaginal cytology, four stages (diestrus, proestrus, estrus, and metestrus) of one mouse estrous cycle could be identified (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) (21). Currently, understanding of endometrial epithelial structure, cellular composition, and dynamic change over mouse estrous cycles is limited and based on 2D tissue sectioning (22). Here, I have carried out an in-depth characterization of mouse endometrial epithelium using whole-mount uterine tissue analysis. Adult wild-type (∼8- to 10-wk-old mice) uterine horns were cut open along the mesometrial line (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-EpCAM antibody to specifically label endometrial epithelia for whole-mount analysis. Multiangle observations revealed that individual uterine glands surrounded by the stromal tissue distributed apart from each other (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). A straight neck from each gland stretched up toward the lumen surface (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Here, a uterine epithelial structure was defined based on the 3D analysis: the intersection zone between luminal and glandular epithelial compartments. It is an open ring structure connecting both luminal epithelium and gland (Fig. 1B and Movie S1). The intersection zone, one gland and attached luminal epithelium, construct the basic epithelial unit (Fig. 1C). Individual uterine epithelial units (Fig. 1C) could be dissected out based on EpCAM fluorescence signal. After mechanical dissociation of the coiled section, the gland became loose (Fig. 1D). Structural properties of uterine epithelial units were documented using confocal and electron microscopy: the gland is a tubular structure composed of a single layer of epithelial cells enclosed by a thin layer of basement membrane (Fig. 1 E–G), which differs from mammary glands (23) and sweat glands (24), which contain a bilayer of distinct epithelial cell types.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of mouse uterine endometrial epithelium. (A) Representative mouse uterine epithelia labeled with EpCAM antibody (epithelial marker, green), FOXA2 antibody (glandular-specific marker, red), and DAPI (nuclei, blue) in a wild-type uterine tissue section. Higher magnification of the glandular neck indicated in the dotted square in the Left merge panel is shown on the Right. (B, Upper) Intersection zone (indicated by arrow) between the luminal epithelial compartment and glandular tissue. (B, Lower) Higher magnification of the intersection zone circled on the Left. (C) A representative intact uterine epithelial unit dissected from adult wild-type uterus, stained with EpCAM antibody (green) and laminin antibody for basement membrane (magenta). (D) A representative loose uterine epithelial unit post manual dissociation of the coil compartment, stained as in C. (E) Higher magnification of glandular neck and intersection zone (circled by square) from the image in large dotted square in image D. (F) Higher magnification of glandular branch from the image in small dotted square in image D. (G) Microstructure of glandular tube by electron microscopy. Arrow indicates basement membrane. (H) Schematic of mouse uterine epithelial unit. (I) Cellular composition of intersection zone (Top view). Green indicates luminal cells, magenta indicates glandular cells. Data were collected from at least five adult wild-type mice for each independent experiment. (Scale bar, 2 μm in G and 50 μm in all other images.)

The uterine epithelial units undergo dynamic changes over one estrous cycle. From diestrus, proestrus, to estrus, more (34 vs. 43 vs. 54 glands per longitudinal uterine tissue section) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and C) and larger glands (50 vs. 81 vs. 156 cells per middle cross-section of a single gland) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and D) gradually appeared, driven by high rates of cell proliferation, as assessed by Ki67+ proliferating glandular cells (13% vs. 38% vs. 52% vs. 18% Ki67+ glandular cells in total glandular cells) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and E). During this process, uterine glands became branched (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) and glandular necks gradually opened from cord to duct (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). These changes prepare the glands for the secretion and prompt release of key factors such as leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) into the uterine lumen to establish an optimal environment for successful embryo implantation (25). So, structural defects or malfunction of uterine glands results in failure of implantation (25, 26). Luminal epithelia attached to each gland also experienced considerable proliferation and differentiation during each estrous cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The number of luminal epithelial cells increased approximately ninefold within each cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D) and the luminal epithelial surface became increasingly folded with deep crypts from diestrus to estrus (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Meanwhile, dynamic epithelial cell populations including EpCAM+;FOXA2− luminal epithelia and EpCAM+;FOXA2low glandular epithelia gradually constituted the intersection zone (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) along with proliferation and differentiation of endometrial epithelia over the mouse estrous cycle. All of the results showed that uterine epithelial units (Fig. 1 H and I) form the whole endometrial epithelium and undergo repeated cycles of basal-to-maximal proliferation and differentiation to maintain homeostasis, regeneration, and function of the uterus.

Genetic Marking of Single Epithelial Cells in Whole Mouse Uterus.

To understand a single epithelial cell’s behavior and fate over one uterine estrous cycle, an in vivo CreERT2-LoxP–based single-cell marking system was established in the mouse uterus. Antibody screening in adult wild-type uterine tissue, combined with mouse genetic screening using CreERT2-LoxP, revealed that Keratin19 was expressed in both the LE and GE of the uterus (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Thus, Keratin19:CreERT2;RosaYFP/+ mice were used to lineage label epithelial cells. In the CreERT2-LoxP system, cell-labeling efficiency is positively correlated to tamoxifen dosage; a lower dose of tamoxifen injection leads to fewer cells being labeled (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (27). Such single-cell labeling system has been applied in mouse ovary to faithfully trace a single germ cell’s behavior and fate under physiological condition (28, 29). In the present study, to randomly label a few isolated single epithelial cells in a whole mouse uterus, titrating tamoxifen in ∼8- to 10-wk-old Keratin19:CreERT2;RosaYFP/+ mice revealed that a single low dose of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g body weight), being injected at the diestrus stage, resulted in an average of 32 single epithelial cells marked by YFP in one uterine horn at 12 h posttamoxifen injection (Fig. 2 A–C and J). Of those cells, 81% were LE and 19% were GE (Fig. 2M). Alignment of serial uterine tissue sections indicated that these YFP-labeled single epithelial cells were spatially distributed apart from each other at a distance of ≥481 µm (Fig. 2 D and K). Such scattered distribution avoided overlap among their progeny clones to allow us to track each single cell’s behavior and fate individually. Although uterus tissue is sensitive to tamoxifen (30), no uterine defect was observed during estrous cycles at this low level of tamoxifen administration.

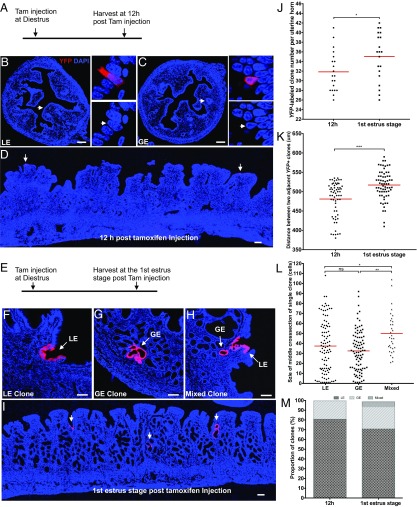

Fig. 2.

Fate of single endometrial epithelial cell during uterine regeneration. (A) Experimental design for single epithelial cell marking. A single low dosage of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g mouse body weight) was given to adult Keratin19CreERT2;Rosa26YFP/+ mice (n = 20) at diestrus, then uteri were collected at 12 h posttamoxifen injection for analysis. (B) Single luminal epithelial cell (LE) and (C) single glandular epithelial cell (GE) were marked by yellow fluorescent protein (YFP, red color) at 12 h posttamoxifen injection. (Insets) Higher magnification of single epithelial cells marked by YFP. (D) Widely distributed YFP-labeled single epithelial cells. (E) Experimental design for single epithelial cell tracing over one estrous cycle. A low dosage of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g body weight) was given to adult Keratin19CreERT2;Rosa26YFP/+ mice (n = 20) at diestrus, then uteri were collected at the first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection for analysis. (F) A representative luminal epithelial clone (LE clone). (G) A representative glandular epithelial clone (GE clone). (H) A representative mixed clone (MC) containing both luminal and glandular epithelia. (I) The YFP-labeled epithelial clones, indicated by arrows, are widely separated at the first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection. (J) Number of YFP-labeled clones at 12 h or first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection, which is shown as clone number per uterine horn. Each point represents an average from two uterine horns of a single mouse (n = 20). Unpaired t test was applied here for the data assessment. (K) Distance between two adjacent YFP+ clones at 12 h or first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection. Mann–Whitney U test was applied here for the data assessment. (L) Size distribution of three types of epithelial clones at first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection, which is shown by the number of YFP+ cells in the middle cross-section of a single clone. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test was applied here for the data assessment. (M) Proportion of three types of clones at 12 h or first estrus stage posttamoxifen injection. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; P > 0.05, not significant (ns). (Scale bar, 100 μm in all images.)

YFP-Labeled Single Epithelial Cells Follow Distinct Fates.

When the fates of these YFP-labeled single cells were followed from diestrus to estrus over one estrous cycle (Fig. 2E, labeled at diestrus phase, examined at the first following estrus phase), all of the YFP-labeled cells generated epithelial clones (on average, 35 clones per uterine horn vs. 32 initially labeled single cells; Fig. 2J) that varied in size and property (Fig. 2 F–H and L). Three types of clones were derived from the YFP-labeled single epithelial cells (Fig. 2 F–H and M): 72% contained only LE cells (LE clones) (Fig. 2 F and M), 23% contained only GE cells (GE clones) (Fig. 2 G and M), and 5% contained both LE and GE cells (mixed clones) (Fig. 2 H and M). These clones distributed separately (Fig. 2I) as their founder cells did; the distance between two adjacent YFP+ clones (517 µm, Fig. 2K) was larger than that between two adjacent initially YFP-labeled single cells (481 µm, Fig. 2K), which is likely because the uterine horn expanded in volume from diestrus to estrus (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Clone size (reflected by number of YFP+ cells per middle cross-section of single clone) varied across a broad distribution (Fig. 2L). Compared with LE clones (37 cells per clone) or GE clones (32 cells per clone), the mixed clones (48 cells per clone) are larger in size (Fig. 2L), indicating that founder cells of mixed clones have a higher proliferative capacity. The variable size and diverse cellular identities of these clonal progeny reflected that individual epithelial cells of the mouse uterine endometrium are at any point in time in different proliferation and differentiation states, excluding the possibility that the endometrial epithelium is maintained by a large population of identical cells.

YFP-labeled cells were not observed in the endometrial stroma and myometrium compartments, revealing that epithelial cells likely do not contribute to these lineages, and that perimetrial cells do not contribute to YFP+ endometrial epithelia, even though Keratin19 labeled cells in the perimetrium (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The apparent lack of exchange/migration of cells between perimetrium and endometrium is consistent with the perimetrium being physically separated from the endometrium by the myometrium (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C).

Founder Cells of Mixed Clones Persistently Regenerate Epithelial Lineages.

To determine if the YFP-labeled endometrial epithelial cells can survive cyclical uterine tissue turnovers to support the repeated regenerations of endometrial epithelia, YFP-labeled single cells were monitored for extended periods (Fig. 3A: 120 d/24 cycles, 240 d/48 cycles and 360 d/72 cycles, based on the 5-d mouse uterine cycle) (21). Surprisingly, the mixed clones persisted for multiple estrous cycles and sustained the repeated reexpansion of the endometrial epithelia (48 cells vs. 373 cells vs. 501 cells vs. 638 cells per mixed clone, Fig. 3 B, C, and E). Larger regions of the endometrial epithelium, including both surface luminal epithelium and glands, were gradually populated by YFP+ cells over multiple estrous cycles (Fig. 3 C and E). However, both luminal and glandular clones decreased in size (37 vs. 8 cells per luminal clone, 32 vs. 6 cells per glandular clone, Figs. 2L and 3F) and in number (22 vs. 4 luminal clones, 7 vs. 3 glandular clones per uterine horn, Figs. 2 J and M and 3G) during this long term of trace. Clearly, mixed clones were able to survive, whereas luminal and glandular clones were easily lost over cyclical uterine tissue turnovers, suggesting that founder cells of mixed clones are capable of life-long maintenance of the self-renewing endometrial epithelium.

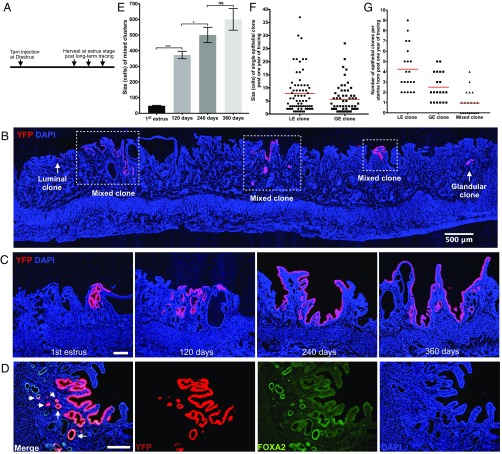

Fig. 3.

Mixed clones persist over uterine tissue turnovers. (A) Experimental design for long-term tracing of single epithelial cells. A low dosage of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g body weight) was given to adult Keratin19CreERT2;Rosa26YFP/+ mice (n = 30) at diestrus, then 10 each of these uteri were collected in estrus stage at day 120, day 240, and day 360 posttamoxifen injection for analysis. (B) A representative Keratin19:CreERT2;RosaYFP/+ mice uterine horn post 1 y of tracing. Mixed clones marked by squares. Luminal or glandular clones are shown by arrows. (C) Representative fluorescent images of single mixed clones at estrus stages post one cycle, 120 d, 240 d, and 360 d of tracing. (D) Representative fluorescent image of a single mixed clone stained with lineage marker YFP (red) and glandular-specific marker FOXA2 antibody (green). Arrows in merged panel (Left) indicate FOXA2+ glandular cells. (E) Size of single mixed clones over a lifetime of tracing, shown by number of YFP+ cells in the middle cross-section of each single clone. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was applied here for the data assessment. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; P > 0.05, not significant (ns). (F) Size of single luminal or glandular clones after 1 y of tracing, shown by number of YFP+ cells in the middle cross-section of each single clone. (G) The number of three types of epithelial clones in one uterine horn after 1 y of tracing. (Scale bar, 500 μm in B and 100 μm in all other images.)

Founder Cells of Mixed Clones Cycle Slowly and Are Bipotent.

Sustaining a stable pool of stem cells by stem cell replacement ensures tissue maintenance and helps prevent stem cell loss during aging or because of injury (19, 31, 32). Mixed clones expand in size over a lifetime of tracing, likely attributable to replacement of stem cells. This dynamic expansion of mixed clones over 1 y of tracing (Fig. 3 C and E) allowed the calculation of the cycling rate of their founder cells. This cell population cycled slowly, duplicating approximately once every 8 estrous cycles: each YFP-labeled founder cell generated a mixed clone containing 48 cells after 1 cycle on average; this mixed clone expanded to 373 cells after 24 cycles (Fig. 3E), implying that ∼8 founder cells (373/48) were generated after 24 cycles, and that this expansion required 2.8-cell divisions (2√8), therefore, 8 uterine cycles per division (24 cycles per three divisions). This result rules out the possibility that initiation of founder cell division of mixed clones is induced by steroid hormones; otherwise they will divide every cycle under the cyclical stimulation of steroid hormones.

Histological analysis indicated that mixed clones contained both luminal and glandular epithelia (Figs. 2H and 3C). Anti-FOXA2 antibody staining showed that mixed clones derived from YFP-labeled single epithelial cells were composed of both FOXA2− LE cells and FOXA2+ GE cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, the founder cells of mixed clones are bipotent; luminal and glandular epithelia, which coordinately construct endometrial epithelium, have a common cellular origin.

Founder Cells of Mixed Clones May Reside in the Intersection Zone.

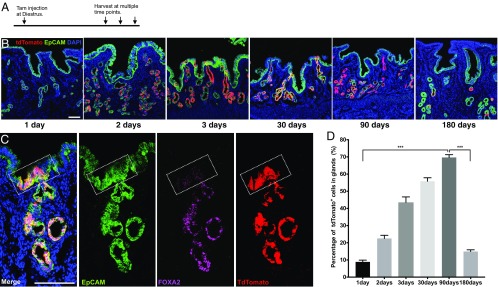

To further define the identity of the founder cell population of mixed clones, I traced the differentiation of uterine glandular cells using Foxa2:CreERT2 mice to determine whether glandular cells could contribute to luminal epithelium. After crossing with a reporter mouse line RosatdTomato/tdTomato, a single dose of tamoxifen (4 mg per injection) was given to ∼8- to 10-wk-old Foxa2:CreERT2;RosatdTomato/+ mice at diestrus stage to extensively label glandular cells (Fig. 4A). As uterus is a hormone-sensitive tissue (30), cystic endometrial hyperplasia was found in the uteri of some animals when using this tamoxifen dose. Based on the data collected from the rest of normal Foxa2:CreERT2;RosatdTomato/+ animals, tdTomato-labeled glandular cells expanded from an initial 10% of the glandular cell population on day 1 to 70% on day 90 (after 18 estrous cycles) posttamoxifen induction (Fig. 4 B and D). During tracing, tdTomato signal was restricted to FOXA2-expressing epithelial cells in both glands and intersection zone (Fig. 4 B and C). Thus, FOXA2+ glandular epithelia did not contribute to luminal epithelium under physiological condition. Further tracing showed that tdTomato-labeled glandular cells were significantly reduced to 15% of total glandular cells by day 180 (after 36 uterine cycles) (Fig. 4 B and D), indicating that tdTomato-labeled resident glandular cells could transiently support homeostasis and regeneration of uterine glands, but to maintain long-term regeneration of glandular epithelium, a persistent supply of uterine glandular cells from founder cells of mixed clones is required. So, FOXA2+ glandular compartment does not contain founder cells of mixed clones.

Fig. 4.

Founder cells of mixed clones do not exist in the glandular compartment. (A) Experimental design for tracing glandular cells. A single dosage of tamoxifen (4 mg per mouse) was given to adult Foxa2CreERT2;Rosa26Tom/+ mice at diestrus, then uteri were collected at estrus stage at multiple time points posttamoxifen injection for analysis. (B) Representative fluorescent images of uterine tissue after tracing of 1 d, 2 d, 3 d, 30 d, 90 d, or 180 d. Uterine tissues were collected from at least four mice at each time point for analysis. (C) Lineage marker tdTomato (red) is restricted to FOXA2+ cells (magenta). A representative tdTomato-labeled uterine epithelial unit stained with EpCAM (green) antibody, FOXA2 specifically labels glandular cells (magenta). The intersection zone is highlighted by a white square. (D) Percentage (%) of tdTomato+ glandular cells in total glandular cells at multiple time points posttracing. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was applied here for the data assessment. ***P < 0.001. (Scale bar, 100 μm in all images.)

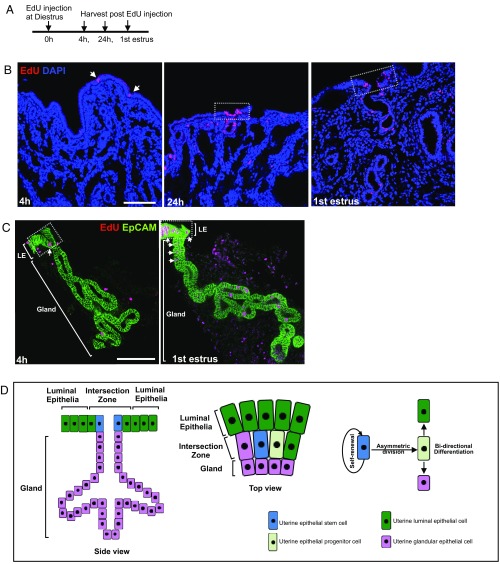

To more precisely locate founder cells of mixed clones, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) pulse-chase experiments in both whole uterine tissue and individual epithelial units were carried out (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). EdU incorporation occurred mainly in epithelial cells (arrows in Fig. 5 B and C) within the intersection zone 4 h post EdU injection at the diestrus stage, and then spread bidirectionally toward both the surface luminal epithelia and glandular neck to form EdU+ epithelial clusters at 24 h and the following estrus phase (white squares, Fig. 5 B and C). Similar epithelial proliferation patterns were also observed in Ki67-stained uterine tissue over one estrous cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). These results revealed that founder cells of mixed clones were likely located in the intersection zone between LE and GE compartments (Fig. 5D). This location explained well the dynamic cellular composition of the intersection zone over one estrous cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 5.

Founder cells of mixed clones may reside in the intersection zone. (A) Experimental design for the EdU chase experiment. A single EdU injection of 0.5 mg per mouse was given to ∼8- to 10-wk-old wild-type mice at diestrus; uterus tissue was collected at 4 h, 24 h, and the first estrus stage postinjection (n = 5 animals per time point). (B) EdU (red) detected in uterine tissue with EdU+ epithelial cells in the intersection zone indicated by arrows (4 h). EdU+ epithelial clusters are indicated in dashed squares at 24 h or first estrus stage, which also include the intersection zone. (C) Single glands (n = 80 per time point) dissected from EdU-treated uterine tissue were used for 3D analysis. EdU+ epithelial cells (4 h) or clusters (first estrus stage) in the intersection zone are indicated by arrows, and the intersection zone by the square. (D) Schematic of mouse uterine endometrial epithelium, epithelial stem cell distribution, and behavior of uterine epithelial stem cells. (Scale bar, 100 μm in all images.)

Founder Cells of Mixed Clones Regenerate Injured Endometrial Epithelium.

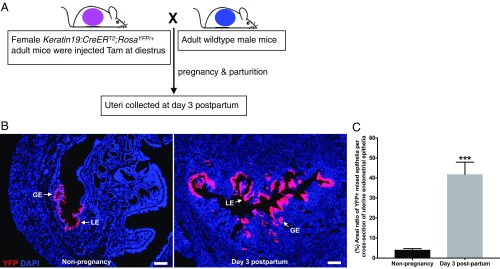

Pregnancy and parturition provide a natural uterine endometrial injury and regeneration model (33). To examine whether or not YFP-labeled single cells are able to support the endometrial epithelium after parturition when the endometrium is undergoing injury-induced regeneration, adult Keratin19:CreERT2;RosaYFP/+ mice were given a single low dose of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g body weight) at the diestrus stage and mated with wild-type male mice (Fig. 6A). Uteri were then collected at day 3 postpartum. Large mixed epithelial clusters including both LE and GE were derived from YFP-labeled single epithelial cells (Fig. 6B), and significantly more area of the endometrial epithelium was occupied by YFP-labeled mixed epithelial clusters in the endometrium postpartum than in nonpregnancy (Fig. 6 B and C). Thus, founder cells of mixed clones provide both a regenerative function during regular repeated uterine cycles and support regeneration of injured endometrial epithelium after parturition.

Fig. 6.

Founder cells of mixed clones regenerate the injured endometrial epithelium post parturition. (A) Experimental design for tracing YFP-labeled epithelial cells during regeneration of endometrial epithelium postpartum. A single low dosage of tamoxifen (0.01 mg/g body weight) was given to adult Keratin19CreERT2;Rosa26YFP/+ mice at diestrus, then they were mated with adult wild-type male mice for establishment of pregnancy. (B) Representative fluorescent images of uterine tissues from nonpregnant (n = 5) and postpartum mice (n = 4). Uteri were collected on day 3 post parturition for analysis. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (C) Areal percentage of YFP+ mixed epithelia per cross-section of uterine endometrial epithelia. P value from unpaired t test is provided as ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Understanding uterine regeneration has been complicated by the absence of a direct method for analyzing the fate of uterine cells under physiological conditions. Here, I have established a single-cell lineage tracing system in the mouse uterus to reveal a uterine epithelial stem cell population that drives endometrial epithelial regeneration. These stem cells are bipotent, persistent, and generate a complete endometrial epithelial lineage, including surface luminal epithelia and glands embedded in the stroma, thereby maintaining the mouse endometrial epithelium.

Adult stem cells maintain tissues that are continually lost during normal homeostasis, or sporadically through injury. The niches where tissue stem cells reside preserve their indefinite self-renewal ability by providing the appropriate microenvironment and molecular cues (15, 19, 31, 32). Therefore, over tissue turnover, stem cells behave uniquely to generate stem cell clones distinct from the transient nonstem cell clones. Stem cell clones are generally large in size, long lived, and contain progeny in multiple differentiation states. In contrast, transient clones derived from nonstem cells are usually small and variable in size, short lived, and mainly contain fully differentiated cells (14, 19). Identifying stem cell clones in the lineage analysis, as the golden standard of stem cell identification (9, 14–19), has allowed me to identify stem cells within uterine tissues. The mixed clones derived from YFP-labeled single epithelial cells in the mouse endometrium possess all of the properties of stem cell clones. After one estrous cycle of chase, the mixed clones are larger than either luminal or glandular clones, indicating that the founder cells of mixed clones have a high proliferative potential (Fig. 2). Life-long tracing results demonstrate that mixed clones are able to survive cyclical uterine tissue loss, revealing that founder cells of mixed clones can self-renew and continually proliferate and differentiate to form stable clonal progeny with endometrial tissue turnovers (Fig. 3). In contrast to mixed clones, the founder cells of luminal or glandular clones have a limited proliferative ability; thus clones diminish in size with time, and their clonal lineages were easily lost during uterine tissue turnovers (Fig. 3). Histology assessment and FOXA2 staining reveal that mixed clones derived from YFP-labeled single epithelial cells contain two distinct epithelial lineages (luminal and glandular), indicating that founder cells of mixed clones are bipotent (Figs. 2 and 3). Mathematical analysis suggests that founder cells of mixed clones cycle slowly. These various properties demonstrate that mixed clones are stem cell clones, a notion reinforced by their ability to support the injured uterine regeneration post parturition (Fig. 6). Thus, the founder cells persistently generating the mixed clones represent a uterine epithelial stem cell population.

Previous studies have claimed to identify epithelial progenitor cells principally as label-retaining cells in the mouse endometrium (13). When labeled by histone 2B-GFP, these label-retaining epithelial cells lose their label within 2–4 wk (5, 6), suggesting two possibilities: (i) the label-retaining cells are washed out after 2–4 wk, or (ii) they are still present but the label has been diluted to a point where it is no longer detectable. If possibility i is correct, the label-retaining epithelial cells are easily lost, they are short lived, unlike stem cells, which generally have a long lifespan (19) such as the uterine epithelial stem cells identified here (Fig. 3). If possibility ii is correct, the label-retaining epithelial cells have substantially diluted the label within 2–4 wk, suggesting they divide at a high frequency, not according to the expectation that label-retaining cells divide infrequently (4–6). Based on the cycling rate of uterine epithelial stem cells identified here (dividing once every eight cycles, the equivalent of 6 wk), the histone 2B-GFP label should be retained within 2–4 wk in these stem cells. Thus, the uterine epithelial stem cells identified by single-cell lineage tracing in the current study appear to be distinct from these label-retaining adult uterine epithelial cells. When labeled by BrdU in early postnatal uteri, few label-retaining uterine epithelial cells persist beyond the subsequent developmental stages, and undergo division when the uteri reach adult stage (4, 34). As the single layer of epithelia in early postnatal uteri may provide the precursors for the adult endometrial epithelium, it is possible that these rare label-retaining cells may contribute to the establishment of the adult uterine stem cell pool, but further evidence, through lineage tracing, regarding the identity of these label-retaining cells is needed. Recently, single-cell sequencing of uterine epithelia has suggested that aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (ALDH1A1) is correlated with a cell population with stem/progenitor properties during early development of the uterine epithelia (postnatal day 7) (35). However, evidence that these ALDH1A1+ epithelial cells are able to survive the postnatal process of uterus formation/development to contribute to endometrial epithelium in the adult uterus is lacking. The lack of ALDH1A1 expression in adult uterine tissue clearly differentiates these cells from the adult uterine epithelial stem cells identified here. CD44+ epithelial cells able to survive hormonal deprivation and generate gland-like structures in a tissue reconstitution assay have been claimed as a potential uterine progenitor cell candidate (2). These CD44+ cells do not express estrogen or progesterone receptors, a property that the uterine epithelial stem cells identified here most probably have, based on their cycling rate (dividing approximately once every 40 d, Fig. 3E). This steroid hormonal unresponsiveness of uterine epithelial stem cells may be required for the homeostasis stability of uteri during cyclical estrogen stimulation. A certain degree of overlap may exist in both cell populations, and in situ fate determination of CD44+ cells by lineage tracing will reveal whether they can self-renew and differentiate into the complete uterine epithelial lineage as these uterine epithelial stem cells do. In addition to these proposed resident cell sources, the exogenous supply of bone marrow cells, through tissue transplantation from a donor animal, has led to the suggestion that bone marrow cells are able to contribute to uterine regeneration (12, 36). Whether or not the conditions experienced by the uterus during tissue transplantation reflect physiological conditions will be critical in determining if such an exogenous cellular supply plays a role in supporting normal cyclical uterine regeneration, which the current study is focused on.

The discovery of murine adult uterine epithelial stem cells will facilitate the further exploration of the cellular mechanisms underlying human uterine regeneration. A stable resident tissue stem cell pool must be maintained in both human and mouse to fuel cyclical endometrial regeneration, regardless of the fact that human endometrium experiences shedding, whereas apoptosis and reabsorption occurs in mouse endometrium (2, 37). In humans, the regions equivalent to the mouse uterine epithelial intersection zone are shed during menstruation; therefore potential stem cells should be located in the endometrial basalis layer, a founder compartment for cyclical uterine tissue regeneration. Recent studies have shown that stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA-1) and N-cadherin may mark human endometrial epithelial progenitor cells in the basalis layer and contribute to endometriosis progress, a common benign gynecological disease (38, 39). These findings imply that a stem cell population functionally equivalent to the mouse uterine epithelial stem cells identified here exists within the SSEA-1+ and N-cadherin+ basal epithelial progenitor cells, supporting normal uterine tissue homeostasis or, when perturbed, uterine diseases progress such as uterine cancer and endometriosis. Although uterine epithelial stem cells may be located in different area in human and mouse, a common characteristic such as potency may be shared as being bipotent to generate the whole uterine endometrial epithelia lineage. Thus, comparative studies of mouse and human uterine stem cells should advance our understanding of uterine biology and potentially provide a route to uterine regenerative medicine.

Combining all of the data, I propose the following working model of endometrial epithelial regeneration over mouse uterine cycling. To support the expansion of the uterine horn during each cycle, the uterine epithelial stem cells generate early luminal or glandular progenitors in the intersection zone. These progenitors then further differentiate into either luminal epithelial lineage along the lumen surface or glandular epithelial lineage along the neck of gland, thereby maintaining homeostasis and cyclical regeneration of the mouse endometrial epithelium (Fig. 5D).

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Adult 8- to 10-wk-old mice carrying Foxa2:CreERT2 (40), Keratin19:CreERT2 (41), RosaYFP/YFP, and RosatdTomato/tdTomato were used here. Four stages (diestrus, proestrus, estrus, and metestrus) of the mouse estrous cycle are identified based on vaginal smears (21). Lineage tracing was induced by a single tamoxifen injection; control mice were given corn oil without tamoxifen. All procedures involving mice were approved by the Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

Histochemistry and Immunostaining.

For immunofluorescence (42), dissected uteri were fixed in 4% paraformaldyhyde/PBS overnight at 4 °C, washed extensively in PBS, transferred through serial sucrose/PBS, and embedded in O.C.T. compound (Tissue Tek) for cryosectioning. The 10-μm thickness of serial tissue section was made by using a LEICA CM3050S cryostat. For immunostaining, the sections were permeablized in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma)/PBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT), blocked for 1 h in 4% BSA (Sigma)/PBS solution at RT, then incubated with primary antibodies in the blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. The next day, slides were washed three times with PBS (10 min per wash), incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT, washed with PBS three times, counterstained by DAPI for 5 min, washed with PBS three times before mounting in Fluoromount G (SouthernBiotech), and then imaged with a Leica confocal fluorescence scope.

Whole-Mount Uterine Tissue Staining and Dissection of Single Glands.

Mouse fresh uterine horns were opened by cutting along the mesometrial line, then fixed and stained by Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse EpCAM (BioLegend) antibody for 24 h with a gentle shaking at RT under a dark environment. Then the uterine tissue was washed with PBS three times (30 min per time). By a vertical cut, a small piece (1–2 mm thick) from the stained whole uterine horn tissue was used for multiangle imaging. Meanwhile, green single glands labeled by EpCAM could be isolated under fluorescence scope by using two 1-mL syringes with 26-gauge needles. The isolated glands were washed with PBS twice. Then they were mounted and imaged with confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Quantitation and Statistical Analysis.

After alignment of serial uterine tissue-section images, cell numbers of middle cross-section of each clone (cell cluster) were counted based on YFP signal. For the distance of two adjacent clones, the length between two middle cross-sections of two adjacent clones was calculated, based on YFP signal. The size of individual glands is reflected by the cell number of the middle cross-section of each gland; glandular cells were counted based on EpCAM antibody staining signal. Each experiment in the current study was repeated at least three times. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). All statistical data considered significant show P values of <0.05 as assessed by Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparison, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test or Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for comparisons across multiple groups; P > 0.05 means not significant (ns).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank Chen-Ming Fan for manuscript reading; Yukiko Yamashita and her laboratory members, especially Ryan Cummings, for their support on this study; and Guy Riddihough for editing.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1814597116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McLennan CE, Rydell AH. Extent of endometrial shedding during normal menstruation. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;26:605–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janzen DM, et al. Estrogen and progesterone together expand murine endometrial epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2013;31:808–822. doi: 10.1002/stem.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prianishnikov VA. On the concept of stem cell and a model of functional-morphological structure of the endometrium. Contraception. 1978;18:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(78)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan RW, Gargett CE. Identification of label-retaining cells in mouse endometrium. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1529–1538. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson AL, Pru JK. Long-term label retaining cells localize to distinct regions within the female reproductive epithelium. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2888–2898. doi: 10.4161/cc.25917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, et al. Identification of quiescent, stem-like cells in the distal female reproductive tract. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu FF, et al. Isolation and characterization of side population cells in the postpartum murine endometrium. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:629–642. doi: 10.1177/1933719110369180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiel MJ, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not asymmetrically segregate chromosomes or retain BrdU. Nature. 2007;449:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature06115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker N, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golebiewska A, Brons NH, Bjerkvig R, Niclou SP. Critical appraisal of the side population assay in stem cell and cancer stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1738–1750. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Tal R, Pluchino N, Mamillapalli R, Taylor HS. Systemic administration of bone marrow-derived cells leads to better uterine engraftment than use of uterine-derived cells or local injection. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:67–76. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Deane JA. Endometrial stem/progenitor cells: The first 10 years. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:137–163. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohlstein B, Spradling A. The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:470–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature. 2009;460:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature08209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Zhao L, Fish M, Logan CY, Nusse R. Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature. 2015;524:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolis J, Spradling A. Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1995;121:3797–3807. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox DT, Morris LX, Nystul T, Spradling AC. StemBook. IOS Press; Cambridge, MA: 2009. Lineage analysis of stem cells. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kretzschmar K, Watt FM. Lineage tracing. Cell. 2012;148:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byers SL, Wiles MV, Dunn SL, Taft RA. Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke PS, Spencer TE, Bartol FF, Hayashi K. Uterine glands: Development, function and experimental model systems. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19:547–558. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rios AC, Fu NY, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. In situ identification of bipotent stem cells in the mammary gland. Nature. 2014;506:322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu CP, et al. Identification of stem cell populations in sweat glands and ducts reveals roles in homeostasis and wound repair. Cell. 2012;150:136–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelleher AM, Burns GW, Behura S, Wu G, Spencer TE. Uterine glands impact uterine receptivity, luminal fluid homeostasis and blastocyst implantation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38078–38096. doi: 10.1038/srep38078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan J, et al. Tridimensional visualization reveals direct communication between the embryo and glands critical for implantation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:603. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03092-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feil S, Valtcheva N, Feil R. Inducible cre mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;530:343–363. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-471-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei L, Spradling AC. Mouse oocytes differentiate through organelle enrichment from sister cyst germ cells. Science. 2016;352:95–99. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei L, Spradling AC. Single-cell lineage analysis of oogenesis in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1463:125–138. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-4017-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niwa K, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on endometrial carcinogenesis in mice. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1998;89:502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1998.tb03290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: Mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nystul T, Spradling A. An epithelial niche in the Drosophila ovary undergoes long-range stem cell replacement. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang C-C, Orvis GD, Wang Y, Behringer RR. Stromal-to-epithelial transition during postpartum endometrial regeneration. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan RW, Kaitu’u-Lino T, Gargett CE. Role of label-retaining cells in estrogen-induced endometrial regeneration. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:102–114. doi: 10.1177/1933719111414207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu B, et al. Reconstructing lineage hierarchies of mouse uterus epithelial development using single-cell analysis. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:381–396. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor HS. Endometrial cells derived from donor stem cells in bone marrow transplant recipients. JAMA. 2004;292:81–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood GA, Fata JE, Watson KL, Khokha R. Circulating hormones and estrous stage predict cellular and stromal remodeling in murine uterus. Reproduction. 2007;133:1035–1044. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valentijn AJ, et al. SSEA-1 isolates human glandular epithelial cells: Phenotypic and functional characterization and implications in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2695–2708. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen HPT, et al. N-cadherin identifies human endometrial epithelial progenitor cells by in vitro stem cell assays. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2254–2268. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park EJ, et al. System for tamoxifen-inducible expression of cre-recombinase from the Foxa2 locus in mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:447–453. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Means AL, Xu Y, Zhao A, Ray KC, Gu G. A CK19(CreERT) knockin mouse line allows for conditional DNA recombination in epithelial cells in multiple endodermal organs. Genesis. 2008;46:318–323. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin S, Martinelli DC, Zheng X, Tessier-Lavigne M, Fan CM. Gas1 is a receptor for sonic hedgehog to repel enteric axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E73–E80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418629112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.