Significance

Plasmodium vivax infects humans by interacting with the Duffy blood group antigen (Duffy antigen) that is expressed on erythrocytes. Duffy antigen is absent in most Africans; hence, P. vivax infection is rare in Africa. However, low levels of P. vivax infections have been observed throughout Africa, suggesting that an alternative invasion pathway may be utilized to infect Africans. Duffy binding protein 1 binds to Aotus but not Saimiri erythrocytes, suggesting the involvement of an alternate invasion pathway in Saimiri infections. Hence, we performed comparative transcriptomics between Aotus- and Saimiri-infected P. vivax to identify these alternate invasion ligands. Transcriptomic analysis has identified genes belonging to tryptophan-rich antigen and merozoite surface protein families, which may play an important role in P. vivax infection in Africans.

Keywords: Plasmodium vivax, Duffy binding protein, Duffy blood group antigen, Saimiri, Aotus

Abstract

Unlike the case in Asia and Latin America, Plasmodium vivax infections are rare in sub-Saharan Africa due to the absence of the Duffy blood group antigen (Duffy antigen), the only known erythrocyte receptor for the P. vivax merozoite invasion ligand, Duffy binding protein 1 (DBP1). However, P. vivax infections have been documented in Duffy-negative individuals throughout Africa, suggesting that P. vivax may use ligands other than DBP1 to invade Duffy-negative erythrocytes through other receptors. To identify potential P. vivax ligands, we compared parasite gene expression in Saimiri and Aotus monkey erythrocytes infected with P. vivax Salvador I (Sal I). DBP1 binds Aotus but does not bind to Saimiri erythrocytes; thus, P. vivax Sal I must invade Saimiri erythrocytes independent of DBP1. Comparing RNA sequencing (RNAseq) data for late-stage infections in Saimiri and Aotus erythrocytes when invasion ligands are expressed, we identified genes that belong to tryptophan-rich antigen and merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) families that were more abundantly expressed in Saimiri infections compared with Aotus infections. These genes may encode potential ligands responsible for P. vivax infections of Duffy-negative Africans.

Until recently, susceptibility to Plasmodium vivax infections was linked to the expression of the Duffy blood group antigen (Duffy antigen) by the host erythrocytes (1, 2). Duffy binding protein 1 (DBP1) is the only known P. vivax parasite protein that binds to Duffy antigen, and DBP1 is necessary for the invasion of Duffy-positive erythrocytes (3–5). Mutation in the GATA1 binding site in the upstream region of the gene encoding the Duffy antigen resulted in the loss of expression of the Duffy antigen on the surface of erythrocytes (6). The prevalence of Duffy antigen is high in individuals in Asia and South America; hence, the incidence of P. vivax is also high. In contrast, the vast majority of individuals of sub-Saharan African Bantu descent carry the GATA1 binding site mutation and are Duffy-negative, with P. vivax infections being rare in sub-Saharan Africa (7). Thus, the global P. vivax incidence reciprocates Duffy-negative prevalence.

However, Duffy-negative individuals have been diagnosed with P. vivax infections throughout Africa (8–23), in part, because of the development of a sensitive real-time PCR test for P. vivax.

An expansion of the gene encoding DBP1 was recently reported in P. vivax infections of Duffy-positive individuals in Madagascar, Cambodia, Thailand, and Papua Indonesia (24, 25). In addition, an expansion of three and eight copies was observed in Duffy-negative Ethiopians (16). Although the significance of the expansion of DBP1 is unclear, it suggests the possibility that parasites expressing high levels of DBP1 could infect Duffy-negative erythrocytes expressing a low level of Duffy antigen (leaky expression) in these cells. Alternatively, P. vivax may have evolved to use other invasion pathways relying on ligands other than DBP1 (22, 26, 27). P. vivax infections in Duffy-positive individuals are generally benign. However, P. vivax was reported to cause severe disease in humans (28–31), making it a public health priority to understand the mechanism of invasion of emerging Duffy-negative infections by P. vivax. Such studies, however, are limited as there is no long-term culture technique available that allows P. vivax field isolates to grow in vitro. Furthermore, parasitemias in the Duffy-negative P. vivax infections are usually low.

Here, we approach the study of Duffy-negative erythrocyte invasion by P. vivax using monkey models. Saimiri and Aotus monkeys have been widely used to study P. vivax infections. Wertheimer and Barnwell (3) showed that DBP1 from the Belem isolate of P. vivax binds to Duffy-positive Aotus erythrocytes but not to Saimiri erythrocytes. Consistent with these findings Aotus but not Saimiri erythrocytes were able to bind COS cells expressing DBP1 region II (4, 16) or recombinant DBP region II from P. vivax Salvador I (Sal I) (32). Nonetheless, the P. vivax multiplication rate was similar in both Aotus and Saimiri monkeys. Thus, invasion of P. vivax in Saimiri monkey erythrocytes may model DBP1-independent pathways.

The original P. vivax Sal I isolate was derived from an infection in the Cangrejera area located in the department of La Paz in El Salvador; it was adapted to infect Aotus trivirgatus (33) and, later, Saimiri monkeys (34). In this study, we obtained the Aotus- and Saimiri-adapted P. vivax Sal I from the CDC and infected them in Aotus and Saimiri monkeys, respectively. We further performed RNA sequencing (RNAseq) to identify the P. vivax Sal I parasites genes that were differentially expressed in mature parasites, schizonts, in Saimiri and Aotus monkeys. We have identified several genes that are transcriptionally up-regulated in Saimiri that may be involved in P. vivax invading Saimiri erythrocytes.

Results

P. vivax Sal I Infection in Saimiri and Aotus Monkeys.

Several studies have highlighted that Aotus erythrocytes bind efficiently to DBP1 from P. vivax but that Saimiri erythrocytes do not bind Sal I or Belem DBP1 (3, 4, 16, 32). These observations indicate that P. vivax infections in Saimiri utilize invasion ligands other than DBP1. Furthermore, the erythrocyte binding protein (EBP/DBP2), which has a subtelomeric location on chromosome 1, is missing in the P. vivax Sal I isolate (35, 36). We infected two splenectomized Aotus nancymaae and two splenectomized Saimiri boliviensis monkeys with P. vivax Sal I, and the parasite growth kinetics in both Aotus and Saimiri monkeys had similar parasitemia, reaching a peak of around 0.3–1%. Next, we compared P. vivax Sal I infection in Saimiri monkeys with that in Aotus monkeys as a model system to identify potential ligands involved in the invasion of Duffy-negative P. vivax infections in Africa. Despite not binding to Sal I P. vivax DBP1 region II, Saimiri erythrocytes are not Duffy-negative. The GATA1 binding site upstream of the Duffy antigen gene is wild type in Saimiri monkeys, and there is no other mutation that abolishes the expression of Duffy antigen on the surface of the Saimiri erythrocytes (16). In addition, the Duffy-specific Fy6 antibody binds to Saimiri erythrocytes, indicating that the Duffy antigen is expressed on the surface of Saimiri erythrocytes (37, 38). The N-glycanase–treated Saimiri erythrocytes bound Sal I P. vivax DBP1 region II (39). Furthermore, DBP1 from P. vivax strains from India and Brazil bind both Saimiri and Aotus erythrocytes (16).

RNAseq on Saimiri and Aotus Samples.

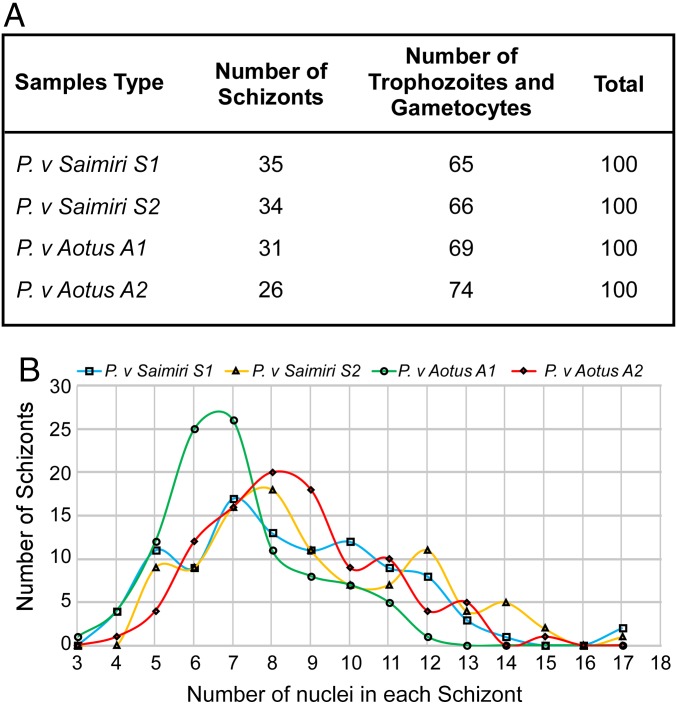

We used RNAseq to determine the differential expression of genes in P. vivax Sal I grown in Saimiri versus Aotus monkeys. Two Saimiri and two Aotus monkeys were infected with P. vivax Sal I. The trophozoite-stage parasites were enriched using magnetic cell sorting (MACS) large size (LS) columns, and the parasites were allowed to mature to the schizont stage in vitro. The parasitemia was determined using Giemsa-stained smears at the time of extraction of mRNA. The proportions of schizonts in the two Saimiri samples were 35% and 34%, with the rest being single nucleated trophozoites or gametocytes (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). No rings were observed. In the two Aotus samples, the proportions of schizonts were 31% and 26% (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Again, no rings were seen.

Fig. 1.

P. vivax Sal I infection in Saimiri and Aotus monkeys. (A) Two Saimiri monkeys and two Aotus monkeys were infected with the P. vivax Sal I parasites. Late schizont stage parasites were purified from monkey blood samples for RNAseq analysis. Following enrichment by culture, a Giemsa smear was performed on two Saimiri and two Aotus infections to evaluate the percentage of schizonts and the stage of schizont development. The table summarizes the proportion of schizont-stage parasites in a total of 100 parasites for all infections studied. (B) Graph shows the number of nuclei in each schizont in two Saimiri and two Aotus P. vivax samples. A total of 100 schizonts were counted for the total number of nuclei per schizont for each sample.

We identified the age of the schizont stage population by determining the number of nuclei (in the range of three to 17 nuclei) within each schizont. The number of nuclei in a total of 100 schizonts for each sample is shown (Fig. 1B). It is clear that the schizonts in the P. vivax-infected Saimiri samples, S1 and S2, and the infected Aotus sample, A2, were at a similar stage. However, P. vivax-infected Aotus sample A1 had a higher proportion of younger, less mature schizonts with a peak of six to seven nuclei each.

RNA was prepared from four samples (A1, A2, S1, and S2) and sequenced using the Illumina platform. The sequence reads were aligned to the P. vivax Sal I reference genome (40, 41). To examine any differences in the vivax sequences of the Aotus- and Saimiri-infected samples, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection was performed in genic regions showing expression (greater than sixfold read depth) in all four samples using the software packages mpileup and bcftools from SAMtools version 1.8 (42). Two variants were detected in the Aotus samples that were not detected in the Saimiri samples. One of the variants (position NC_009917.1:2913728) was a synonymous substitution in PVX_118635, while the second variant (position NC_009917.1:787300) was a nonsynonymous change (V196M) in PVX_082635 (Dataset S1). Neither of these genes was differentially expressed. Next, we examined the aligned reads in three polymorphic genes [apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1), merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1), and DBP1] by means of the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) and confirmed the absence of SNPs in these three genes from the Aotus and Saimiri samples in comparison to the Sal I reference sequence.

Differential Gene Expression Analysis.

Two methods, edgeR and DESeq2, were used to normalize the data for samples A1, A2, S1, and S2 and to determine differential expression at the RNA level and for statistical analysis. The variations or groupings among the RNA sequences of the Aotus and Saimiri samples were analyzed. To do this, principal component analysis (PCA), sample clustering, and multiple dimensional scaling (MDS) were performed on the RNA sequence data. The normalized counts and rlog-transformed data generated with DESeq2 were used to generate a PCA plot and a sample-distance heatmap, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). In the PCA, 79% of the variance between samples is represented by principal component 1 (x axis), with the two Aotus samples on the left and the two Saimiri samples on the right (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The PCA displayed similar results as the MDS plot generated with edgeR (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). The sample clustering shows the Saimiri samples grouped together on a separate branch from the two grouped Aotus samples, indicating that the P. vivax Sal I parasites grown in Saimiri erythrocytes were more similar to each other in their gene expression than to parasites grown in Aotus erythrocytes and vice versa (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

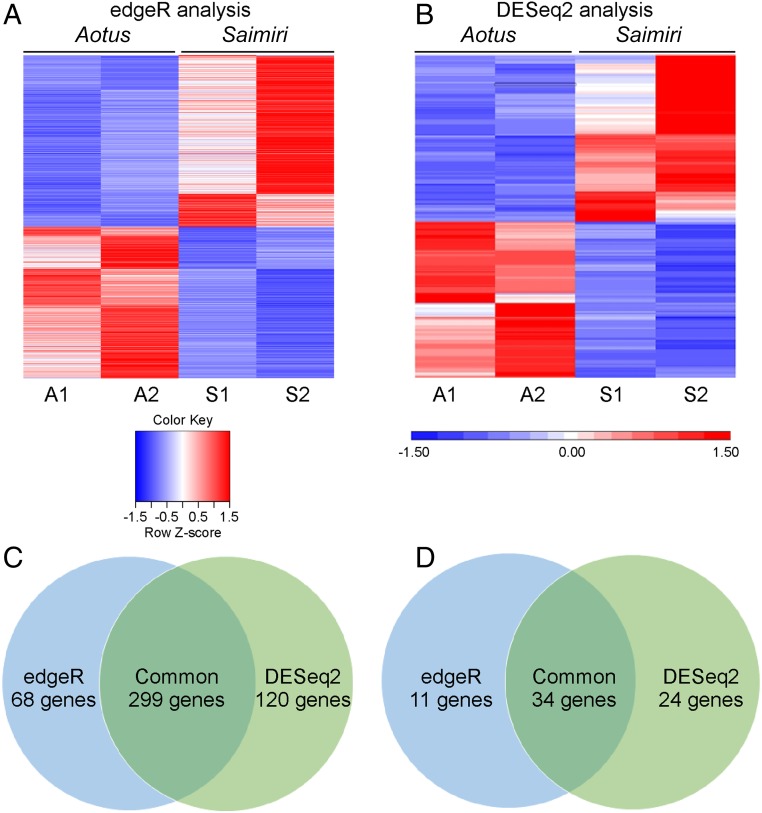

In edgeR analysis, 692 differentially expressed genes were identified (Fig. 2A) and this number was higher for DESeq2, which identified 813 genes (Fig. 2B). Compared with Aotus samples, 367 and 419 genes were more abundantly expressed in P. vivax Sal I Saimiri samples by edgeR and DESeq2, respectively (Fig. 2C). Since there was a difference in the number of genes that were identified as differentially expressed in Saimiri by edgeR and DESeq2, we focused on 299 genes that were identified by both analyses, as shown in the Venn diagram (Fig. 2C). Setting a log2 fold change cutoff of 2, we identified 45 genes more abundantly transcribed in Saimiri by edgeR and 58 genes by DESeq2 analyses, with 34 genes commonly observed (Fig. 2D and Datasets S1 and S2).

Fig. 2.

Differential expression of all genes in Saimiri and Aotus P. vivax infection. edgeR and DESeq2 were used for data normalization and to determine differentially expressed genes between Aotus and Saimiri monkeys. (A) Heatmap generated from 692 significantly differentially expressed genes identified by edgeR analysis. (B) Heatmap generated from 813 differentially expressed genes identified by DESeq2 analysis. (C) Venn diagram shows that the number of genes up-regulated in Saimiri by edgeR is 367 and the number of genes up-regulated by DESeq2 is 419, and that there are 299 genes commonly identified in both analyses (Dataset S1). (D) Venn diagram shows 45 genes up-regulated in Saimiri by edgeR and 58 genes up-regulated by DESeq2, and that there are 34 genes commonly identified in both analyses with a false discovery rate and adjusted P value <0.05 (Datasets S1 and S2).

To reduce possible confounding effects of differences in the number of schizonts in each sample (Fig. 1), the data were adjusted using the remove unwanted variation (RUV) method of the R package RUV-seq (43). Approximately 162 up-regulated and 146 down-regulated differentially expressed genes in Saimiri-infected samples relative to Aotus-infected samples were identified using a k value of 1, a log2 fold change >1.0 or <−1.0, and a false discovery rate-corrected P value <0.05 (Dataset S1). There were no significant differences after the correction. This suggests that the differentially up-regulated genes identified in Saimiri over Aotus were not due to schizont number differences between Saimiri and Aotus samples. Hence, all of the data described below are based on no correction.

From the analysis of P. vivax Sal I in Saimiri and Aotus infections, several genes were shown to be transcriptionally more abundant in Saimiri (>log2 fold change cutoff of 2). In particular, DBP1 in Saimiri was expressed at similar levels in both of the groups and was not significantly different (SI Appendix, Table S1). We also determined that there were no mutations in the DBP1 sequence in both the Aotus and Samiri groups of samples. In addition, another important merozoite protein, AMA1, showed significant abundance in Saimiri but fell below the log2 fold change cutoff of 2 (SI Appendix, Table S1). There are 11 reticulocyte binding proteins in P. vivax (35, 41, 44), and none of the genes were more abundant in P. vivax in Saimiri monkeys above the log2 fold change cutoff of 2 (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Differential Expression of Different Family Members in P. vivax Saimiri Infection.

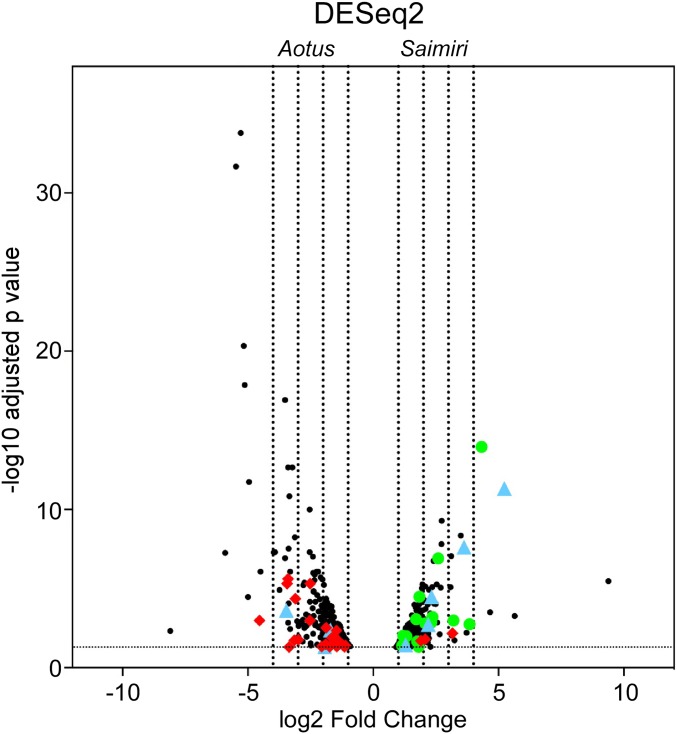

We next determined if any specific gene families, particularly the ones involved in invasion, were differentially expressed in Saimiri compared with Aotus infection. Clear differences were observed in the expression of genes by a volcano plot analysis by DESeq2 (Fig. 3) and edgeR (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Two gene families were particularly more abundantly expressed in Saimiri: the tryptophan-rich antigen family (Pv-fam-a) and the MSP3 family (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Four genes of the 36-member tryptophan-rich antigens in P. vivax were more abundant in Saimiri infection, but only one gene was more abundant in Aotus infection (Table 1). Interestingly, there were 18 MSPs differently expressed, with nine proteins above the log2 fold change cutoff of 2 in Saimiri infection. Surprisingly, there were no MSPs that were differentially expressed in Aotus (Table 2). There was a higher abundance of members of the SERA gene family in Saimiri compared with Aotus infection (SI Appendix, Table S2). In addition, subtilisin-like serine protease 1, which plays a key role during merozoite egress, was differentially expressed in Saimiri (Dataset S1). In summary, of the top five most highly abundant genes expressed in the late-stage parasites in Saimiri, two were from the tryptophan-rich antigen families (37- and 12-fold higher), two were from the MSP3 protein families (20- and 14-fold higher), and one was from the Pv-fam-c protein (13-fold higher) (Dataset S1).

Fig. 3.

Volcano plot showing the differential expression of genes in Aotus and Saimiri P. vivax infection by DESeq2 analysis. The volcano plot represents the significantly differential gene expression (adjusted P value <0.05) of P. vivax schizonts from Saimiri or Aotus monkeys. The horizontal axis represents the expected log2 fold change as estimated by the program DESeq2. The left four vertical dashed lines represent 16-, eight-, four-, and twofold changes in Aotus-derived P. vivax genes, while the right four vertical lines represent two-, four-, eight-, and 16-fold changes in Saimiri-derived P. vivax genes. The red diamonds represent transcripts coding for Vir proteins, the green circles represent transcripts coding for proteins of the MSP3 family, and the blue triangles represent transcripts coding for proteins of the tryptophan-rich family. All genes can be identified in Dataset S1.

Table 1.

Differential expression of tryptophan-rich antigen gene family in Saimiri and Aotus infection

| DESeq2 | edgeR | ||||

| Entrez gene | Description | Log2 fold change | Padj* | Log2 fold change | FDR |

| Saimiri P. vivax infection | |||||

| PVX_112675 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | 5.23 | 4.66E-12 | 4.811999 | 1.6E-08 |

| PVX_112690 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | 3.63 | 2.35E-08 | 3.605041 | 3.7E-07 |

| PVX_112685 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | 2.32 | 3.24E-05 | 2.28251 | 7.92E-05 |

| PVX_121897 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | 2.19 | 1.84E-03 | 2.263585 | 0.002961 |

| PVX_094305 | Tryptophan-rich antigen | 1.74 | 3.59E-02 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_090265 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | 1.29 | 3.54E-02 | 1.558861 | 0.024903 |

| Aotus P. vivax infection | |||||

| PVX_097575 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | −1.71 | 4.18E-03 | −1.793217 | 0.003273 |

| PVX_101525 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | −1.94 | 4.84E-02 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_125730 | Tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a) | −3.46 | 2.39E-04 | −3.521637 | 0.001163 |

The table shows the number of P. vivax tryptophan-rich antigen gene family members that were up-regulated (positive) in Saimiri infection or up-regulated (negative) in Aotus infection with the corresponding log2 fold change by DESeq2 and edgeR analyses. Bold font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 2; italicized font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 1.

Genes with an adjusted P value (padj) <0.05. FDR, false discovery rate.

Table 2.

Differential expression of MSPs in Saimiri infection

| DESeq2 | edgeR | ||||

| Entrez gene | Description | Log2 fold change | Padj* | Log2 fold change | FDR |

| PVX_097670 | Merozoite surface protein 3 gamma (MSP3g) | 4.33 | 1.11E-14 | 4.583926 | 4.5E-13 |

| PVX_097690 | Merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) | 3.84 | 1.81E-03 | 2.189701 | 0.034588 |

| PVX_097680 | Merozoite surface protein 3 beta (MSP3b) | 3.20 | 1.03E-03 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_082675 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 2.59 | 1.22E-07 | 2.545696 | 3.45E-07 |

| PVX_099980 | Major blood-stage surface antigen Pv200 | 2.58 | 9.22E-08 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_124060 | Merozoite surface protein-9 precursor | 2.43 | 8.90E-05 | 2.432973 | 0.00146 |

| PVX_097720 | Merozoite surface protein 3 alpha (MSP3a) | 2.36 | 6.13E-04 | 2.446788 | 0.000849 |

| PVX_097700 | Merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) | 2.31 | 1.41E-03 | 2.631314 | 0.000561 |

| PVX_097710 | Merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) | 2.07 | 1.53E-03 | 2.373412 | 0.000252 |

| PVX_082695 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.84 | 3.21E-05 | 1.82467 | 8.36E-05 |

| PVX_097725 | Merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) | 1.81 | 4.75E-02 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_082680 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.75 | 2.19E-02 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_082650 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.71 | 8.76E-04 | 1.600258 | 0.002781 |

| PVX_082685 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.32 | 1.02E-02 | 1.237558 | 0.022658 |

| PVX_097715 | Merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3) | 1.22 | 3.40E-02 | 1.268078 | 0.03311 |

| PVX_082665 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.19 | 9.47E-03 | 1.195304 | 0.009698 |

| PVX_111355 | Merozoite capping protein 1 | 1.19 | 2.47E-02 | 0 | 0 |

| PVX_082700 | Merozoite surface protein 7 (MSP7) | 1.15 | 4.04E-02 | 1.146387 | 0.038337 |

The table shows the number of MSPs that were up-regulated (positive) in Saimiri infection with the corresponding log2 fold change by DESeq2 and edgeR analyses. Bold font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 2; italicized font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 1.

Genes with an adjusted P value (padj) <0.05. FDR, false discovery rate.

Next, we identified gene family members that were equivalently expressed in both Saimiri and Aotus. In P. vivax, there are eight gene families (Pv-fam-a to Pv-fam-e and Pv-fam-g to Pv-fam-I) (41), and we identified several genes from five of these families that were more abundantly transcribed in either Saimiri or Aotus P. vivax Sal I infection (SI Appendix, Table S3). Several members of this family were equally expressed in Saimiri and Aotus, which may suggest that these family members may not play a role in P. vivax Sal I infection of Saimiri erythrocytes. We also analyzed the gene families in the dataset that were expressed low in Saimiri infection. Interestingly, 23 members of Vir genes were expressed low, while only three Vir genes were highly expressed in Saimiri infections (Table 3). There were four early transcribed membrane proteins (ETRAMPs) that were expressed low in Saimiri (SI Appendix, Table S4). Other than Vir and ETRAMP, no other gene families had low expression in Saimiri. The data obtained in edgeR were consistent with DESeq2 analysis.

Table 3.

Differential expression of Vir genes in Saimiri and Aotus infection

| DESeq2 | edgeR | ||||

| Entrez gene | Description | Log2 fold change | Padj* | Log2 fold change | FDR |

| Saimiri P. vivax infection | |||||

| PVX_021680 | Variable surface protein Vir4 | 3.16 | 6.76E-03 | 2.443797 | 0.043963 |

| PVX_062690 | Variable surface protein Vir18 | 2.07 | 1.57E-02 | ||

| PVX_121855 | variable surface protein Vir18 | 1.90 | 1.99E-02 | 1.499001 | 0.02577 |

| Aotus P. vivax infection | |||||

| PVX_003485 | Variable surface protein Vir4 | −1.11 | 4.04E-02 | ||

| PVX_004539 | Variable surface protein Vir12-related | −1.15 | 4.84E-02 | ||

| PVX_104180 | Variable surface protein Vir12 | −1.24 | 3.37E-02 | ||

| PVX_097555 | Variable surface protein Vir12/16-related | −1.43 | 1.70E-02 | ||

| PVX_133260 | Variable surface protein Vir12, truncated | −1.46 | 3.17E-02 | ||

| PVX_094240 | Variable surface protein Vir12/24-related | −1.46 | 4.66E-02 | ||

| PVX_093710 | Variable surface protein Vir24-related | −1.47 | 4.38E-03 | −1.527948 | 0.006904 |

| PVX_088780 | Variable surface protein Vir24-related | −1.56 | 1.22E-02 | ||

| PVX_005580 | Variable surface protein Vir4 | −1.58 | 2.41E-02 | ||

| PVX_005060 | Variable surface protein Vir12-like | −1.65 | 1.29E-02 | −1.606289 | 0.025872 |

| PVX_115475 | Variable surface protein Vir14 | −1.74 | 4.75E-02 | ||

| PVX_097540 | Variable surface protein Vir24-related | −1.87 | 2.94E-03 | −2.105455 | 0.010348 |

| PVX_083575 | Variable surface protein Vir24-related | −1.90 | 3.29E-02 | ||

| PVX_101570 | Variable surface protein Vir5-related | −2.05 | 4.58E-02 | ||

| PVX_112645 | Variable surface protein Vir17-like | −2.52 | 4.91E-06 | −2.725464 | 8.33E-05 |

| PVX_003495 | Variable surface protein Vir22/24-related | −2.53 | 1.03E-03 | ||

| PVX_001615 | Variable surface protein Vir12/24-related | −2.99 | 1.72E-02 | ||

| PVX_102630 | Variable surface protein Vir27 | −3.11 | 4.40E-05 | −2.988085 | 0.00167 |

| PVX_102640 | Variable surface protein Vir12-related | −3.15 | 1.83E-02 | −3.271886 | 0.03084 |

| PVX_036190 | Variable surface protein Vir34 | −3.36 | 4.86E-02 | ||

| PVX_088790 | Variable surface protein Vir21-like | −3.40 | 2.43E-06 | ||

| PVX_088785 | Variable surface protein Vir12 | −3.44 | 4.91E-06 | ||

| PVX_105710 | Variable surface protein Vir1/9 | −4.54 | 1.03E-03 | −5.602723 | 0.001615 |

The table shows the number of P. vivax Vir genes that were up-regulated (positive) in Saimiri infection or up-regulated (negative) in Aotus infection with the log2 fold change by DESeq2 and edgeR analyses. Bold font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 2; italicized font indicates genes that were up-regulated above a log2 fold change cutoff of 1.

Genes with an adjusted P value (padj) < 0.05. FDR, false discovery rate.

Validation of the Differentially Expressed Genes by Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

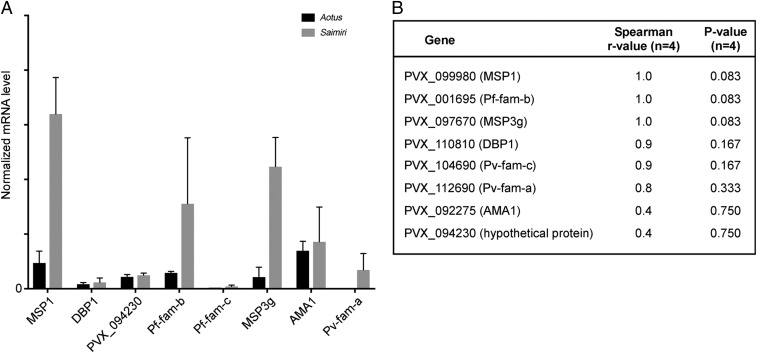

We validated the RNAseq data by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. Each gene signal was normalized to reference glutathione S-transferase (GST) signal following Life Technologies guidelines. We first analyzed the genes listed in SI Appendix, Table S5. We identified three mRNAs that are constitutively expressed at different levels for normalization: alanyl tRNA synthetase (high expression), fumarate hydratase (intermediate expression), and GST (low expression) (SI Appendix, Table S5). The GST primer and probe set performed the best of all three reference gene candidates; therefore, each gene signal was normalized to GST (Fig. 4A). Eight P. vivax mRNAs were compared between the two Saimiri and two Aotus samples: PVX_099980 (MSP1), PVX_01695 (Pf-fam-b), PVX_097670 (MSP3g), PVX_110810 (DBP1), PVX_104690 (Pv-fam-c), PVX_112690 (Pv-fam-a), PVX_092275 (AMA1), and PVX_094230 (hypothetical protein). MSP3g, MSP1, Pf-fam-b, and Pv-fam-a were more abundant in Saimiri compared with Aotus samples by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A). DESeq2-normalized read counts for each of the eight genes were correlated to qRT-PCR values using Spearman correlation (Fig. 4B). Of the eight genes that correlated with the next-generation sequencing data, all showed good Spearman rho correlation, with the exception of PVX_094230 (hypothetical protein) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Validation of RNAseq data by qRT-PCR. (A) qRT-PCR was performed on eight genes from P. vivax Sal I infection in Saimiri and Aotus infection. The normalized mRNA level (averaged) and SD for all eight genes [PVX_099980 (MSP1), PVX_110810 (DBP1), PVX_094230 (hypothetical protein), PVX_01695 (Pf-fam-b), PVX_104690 (Pv-fam-c), PVX_097670 (MSP3g), PVX_092275 (AMA1), and PVX_112690 (Pv-fam-a)] were graphed for each Saimiri and Aotus monkey sample. Each gene signal was normalized to the housekeeping gene GST. Each bar represents an average of two monkeys. The error bar is based on the SD. (B) Table shows the correlation of qRT-PCR and the RNAseq data with the number of samples (n = 4) and P value (significance of correlation).

Discussion

P. vivax has been observed at a low frequency in Duffy-negative Africans across the continent. Although the P. vivax ligands used to invade Duffy-negative erythrocytes are not known, there have been speculations on a number of P. vivax genes encoding potential ligands (reviewed in ref. 22). In some areas, P. vivax has been shown to have an increase in the number of genes encoding DBP1 (16). If the expression of the Duffy antigen is leaky in Duffy-negative Africans, increased expression of DBP1 could allow invasion, selecting for an increase in DBP1 copy number. The distribution of P. vivax in Duffy-negative individuals is unusual in Africa and may mirror the distribution of other P. vivax ligands. For example, in Mali, P. vivax infections in Duffy-negative individuals are limited to around 2% frequency and only in the northern part of the country, near the Sahel (13). In contrast, in central Mali near Bamako, no P. vivax infections were identified in hundreds of people tested with sensitive molecular diagnostics for P. vivax. In Cameroon, P. vivax infections have been found in Duffy-negative individuals throughout the country, and in one area, infections causing fever were found in numerous Duffy-negative Africans (20).

To cast a wide net for parasite invasion ligands, the present study was undertaken to identify parasite ligands in Sal I P. vivax infections in two different monkeys, A. nancymaae and S. boliviensis. While it is evident that Aotus and Saimiri monkeys are Duffy-positive, DBP1 from P. vivax Sal I binds only to Aotus erythrocytes but not to Saimiri erythrocytes (16). This observation mirrors the binding pattern seen for DBP1 binding in humans to Duffy-positive erythrocytes and not to Duffy-negative erythrocytes (3, 4, 16, 32). We hypothesized that the invasion of P. vivax Sal I in Saimiri may model DBP1-independent pathways and that ligands identified by differential gene expression of P. vivax in Saimiri and Aotus may also be involved in invasion of Duffy-negative Africans in whom P. vivax infections are now being observed.

The most critical step in evaluating the differences in expression of Sal I P. vivax in Saimiri versus Aotus monkeys was to determine whether the parasites in the two populations are different in terms of their asexual blood stages of development of rings, trophozoites, or schizonts. The percentage of schizonts was lower in Aotus after culture, and one Aotus (A1) showed a lower number of mature schizonts than the other three infections. However, in expression analysis by PCA and MDS plots, the two Aotus monkeys were similar to each other and different from the two Saimiri monkeys, which were also similar to each other. This suggests that differences in expression were not due to the developmental stage of the parasites, but to the differential expression of certain genes by the parasites.

We used another highly sensitive method to evaluate the developmental stage of the parasites, namely, the expression of late schizont genes, such as the known ligands in invasion (AMA1 and DBP1) and the reticulocyte homology genes. Among these genes, there was a small increase in AMA1 and one of the reticulocyte binding proteins but not above the log2 fold cutoff of 2. These data indicate that there indeed may be some effect of the stage of development on parasite gene expression, but small changes would be unlikely to lead to the large increases observed in the expression of some genes. In addition, a previous study on the MSP3 family of genes showed that the expression of MSP3.1 or MSP3g (the most highly expressed gene in our analyses) was higher in trophozoites than in schizonts (45), although only one infection was performed in each study, making statistical analysis impossible.

In P. vivax, 36 tryptophan-rich antigens (Pv-fam-a) were identified by genome sequencing in Sal I parasites, and their orthologs were present in Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium falciparum, and Plasmodium yoelii (41). So far, functional studies on this family of proteins have only been conducted in P. vivax. Of 36 Pv-fam-a proteins, 10 have been shown to bind to erythrocytes (46, 47). The localization of these 10 proteins was not clear; however, it is predicted to be at the late schizont stage. The interacting partner for some of the Pv-fam-a proteins has been identified to be band 3, basigin, and ETRAMP (48–51). In the current study, tryptophan-rich antigen (Pv-fam-a: PVX_112675) expression in Saimiri infection is 37-fold higher than that of Aotus infection. This protein has been shown to bind to erythrocyte receptor, which is chymotrypsin-sensitive (47), and it was later identified to be band 3 protein in the erythrocytes (52). Furthermore, of the six tryptophan-rich genes expressed higher in Saimiri than Aotus, five were shown to bind erythrocytes (46–48) and PVX_090265 was shown to be highly expressed in clinical isolates (53). The three tryptophan-rich antigens up-regulated in Aotus monkeys did not bind erythrocytes (46, 47). The binding to erythrocytes of the tryptophan-rich antigens was measured by multiple methods, including (i) rosetting of erythrocytes around CHO K1 cells expressing tryptophan-rich antigens in the vector pRE4, (ii) flow cytometry of erythrocytes binding to recombinant proteins, and (iii) inhibition of binding by preincubation with the tryptophan-rich antigen with and without the histidine-rich tag (46–48). The other tryptophan-rich genes did not bind erythrocytes, as evidence that the measurements were unique to these genes (46–48).

There were 11 members of the MSP3 gene family in P. vivax on chromosome 10. All of the MSP3s have a conserved NLRNG sequence present after the signal peptide, followed by coiled-coil structures and a glutamate-rich domain at the C terminus. MSP3s have no transmembrane domains (45). This gene family also has orthologs in P. knowlesi and P. falciparum (41). While all members of MSP3 family were transcribed in the trophozoite and schizont stages, except one gene, all members were translated to protein (45). In our current RNAseq analysis, next to Pv-fam-a, the most abundantly expressed genes in P. vivax in Saimiri infections belong to the MSP3 family (PVX_097670: MSP3g or MSP3.1, PVX_097690: MSP3.5, and PVX_097680: MSP3b or MSP3.3). MSP3.3 and MSP3.5 were shown to be expressed on mature schizont parasites using an immunofluorescence assay. Although the MSP3 family genes have not been shown to bind erythrocytes, it is still possible that these are involved in invasion. In addition to the MSP3 family, we picked up MSP7, MSP1, and MSP9 in our analysis (Table 2). Like in P. falciparum, it will be interesting to see if members from MSP3 interact with MSP1, MSP7, and MSP9 and play an important role in erythrocyte invasion of Saimiri monkeys.

The Vir genes found on the surface of infected erythrocytes (54) were expressed higher in Aotus than Saimiri monkeys. The infected erythrocyte surface proteins of P. falciparum (PfEMP1) and P. knowlesi (SICA) are turned off during passage in splenectomized monkeys (55–57). All infections used in these studies were passaged in splenectomized monkeys. It is possible that the passage in Saimiri monkeys had a greater effect on Vir expression than in Aotus monkeys. This speculation on the effect of splenectomy on expression of Vir genes must await other studies.

The implication of this study on P. vivax infection in Duffy-negative Africans must await a specific search for expression of tryptophan-rich proteins as ligands in Duffy-negative African infections. Furthermore, it must be remembered that DBP2/EBP is expressed in other P. vivax strains and may play a role in invasion of Duffy-negative erythrocytes. The finding of the transcriptomic up-regulation of the tryptophan-rich genes and other possibilities for invasion need to be explored in the years ahead.

Materials and Methods

Study Approval.

All care and use of animals in this study were performed according to the NIH Animal Research Advisory Committee Guidelines, under approved protocols by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee, and in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (58). Splenectomies were performed at least 2 wk before parasite infection. Monkey infections were initiated by i.v. inoculation of 5–100 × 106 parasitized erythrocytes in ≤1.5 mL of saline or RPMI 1640 (KD Medical) into anesthetized animals (i.m. administration of ketamine at a dose of 10 mg/kg). Thin and thick blood smears were checked three times a week until parasites were detected, and then daily. Hematocrit level was monitored weekly, and weight was monitored monthly or whenever an animal was anesthetized. To assess parasitemia, an estimated 10,000 erythrocytes were counted from a thin blood smear; the number of infected erythrocytes was divided by the total number of counted cells and then multiplied by 100 for expression as a percentage value.

Sample Isolation.

The P. vivax sample set consisted of infected erythrocytes from two infected Aotus monkeys and infected erythrocytes from two infected Saimiri monkeys. Briefly, ∼8–10 mL of P. vivax Aotus or Saimiri monkey blood was collected in four 50-mL tubes. The 50-mL tubes were centrifuged at 841 × g at room temperature (RT) for 5 min, and the plasma was removed. Twenty milliliters of incomplete McCoy’s medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) was added to each of the tubes containing a blood pellet and centrifuged at 841 × g for 5 min at RT. This step was repeated two more times. Each pellet in the 50-mL tubes was then mixed with 40 mL of McCoy’s medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). Each 50-mL tube containing the blood suspended in McCoy’s medium was then passed through four MACS LS magnetic columns (Miltenyi Biotech). The columns were washed three times with 5 mL of McCoy’s medium. The trophozoites and schizonts were gently eluted with 5 mL of medium using the plunger provided with the column. The elute was centrifuged at 841 × g at RT for 5 min. A minor fraction of the cells was Giemsa-stained and visualized on the microscope to determine the stage of parasite growth in each of the samples. After MACS purification, the majority of the parasites were at the trophozoite stage. One milliliter of complete medium (37.25 mL of McCoy’s incomplete medium, 297 mg of Hepes, 2.5 mg of hypoxanthine, 12.5 mL of human AB serum, and 0.25 mL of gentamicin at 10 mg/mL) was added and mixed with each parasite pellet. The tube was gassed for 30–60 s with mixed gas (5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2) and kept at 37 °C with shaking for another 8–12 h. A sample of the cells was smeared and Giemsa-stained to determine the percentage of schizonts and the stage of parasite development in each of the samples by visualization under light microscopy. The parasitized erythrocytes were pelleted by centrifuging at 10621 × g at RT for 10 min and then mixed with 1 mL of TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific) and stored at −80 °C. A total of 100 parasites were counted to determine the number of schizont-stage parasites in each sample. To determine the age of the schizont-stage parasites, the number of nuclei in each schizont was counted for 100 schizonts in each sample. The slides for counting the nuclei in schizonts were blinded.

RNA Extraction.

An aliquot of 0.9 mL of TRIzol lysate was combined with 0.2 mL of 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (Sigma–Aldrich), mixed using a Genie Vortex shaker (Scientific Industries) for 15 s, and centrifuged at 4 °C at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The aqueous volume was passed through a QIAGEN QIAshredder column to fragment any remaining genomic DNA (gDNA) in the sample. Six hundred microliters of QIAGEN RLT Buffer containing 1% beta-mercaptoethanol was added to the aqueous-phase solution, and RNA was extracted using a QIAGEN AllPrep 96 Kit as described by manufacturer (QIAGEN), with the exception that each sample was treated with 27 units of DNase I (QIAGEN) for 15 min at RT during extraction to further remove gDNA. Multiple gDNA removal steps were performed to minimize gDNA background signal and to provide an optimal RNA template for next-generation sequencing. All steps were performed in a PCR amplicon-free area with PCR amplicon-free laboratory equipment to further minimize the background signal during the generation of RNAseq libraries. The RNA purity was measured by UV spectrophotometry at 260 nm and 280 nm, and the quantity was measured using an RNA Pico 6000 Kit (Agilent Technologies). RNA quality was also assessed using Agilent’s 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies).

Plasmodium Genome Copy Analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the samples from the organic phase of the TRIzol-treated lysate. To each sample, 300 μL of 100% ethanol was added, mixed, and centrifuged for 5 min at 4 °C and 2,000 × g. The pellet was washed with 1 mL of sodium citrate buffer (0.1 M sodium citrate and 10% ethanol), incubated for 30 min, mixed, and centrifuged for 5 min at 4 °C and 2,000 × g. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol and repurified using the QIAquick 96-well protocol (QIAGEN). The genomic DNA was prepared to determine P. vivax genome copy number.

Malaria genome copy number was determined by qRT-PCR analysis. Briefly, Life Technologies Express qRT-PCR Supermix with premixed ROX dye (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to perform the assays. The reactions were carried out in 20-μL reactions using tubulin beta-chain (PVX_094635) gene forward primer 5′-CTGCTCGTCCACCTCCTTAGTC-3′, reverse primer 5′- CCCGAGACACGGAAGATACCT-3′, and fluorescent probe 5′-CalFluorGold540-TCGTCCTCTAAACATGGCGCAGGC-Black Hole Quencher-3′. The qRT-PCR reactions were carried out at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 2 min, and 55 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The data were analyzed using 7900HT version 2.4 sequence detection system software (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Synthetic DNA representing the PCR amplicon sequence was used as a standard (LCG Biosearch Technologies). The copy number was determined by the standard curve method according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies). Genome copy number and RNA yield values were used for selecting the samples for the next-generation sequencing.

Sequencing Library Preparation and Data Analysis.

Sequencing libraries were prepared from total RNA from two Aotus monkey infections and from two Saimiri infections using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, mRNA was purified by poly(A) selection from 600 ng of total RNA and then fragmented for 8 min at 94 °C. cDNA was generated with random hexamers, and indexing adapters were added to facilitate multiplexing sequencing. The adapter-ligated cDNA products were enriched using 15 cycles of PCR, as specified in the user’s guide. Purified libraries were quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems) and the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), and were combined in equimolar amounts for sequencing on the HiSeq 2500 instrument. The libraries were sequenced using a paired-end run (2 × 75) with Rapid v2 chemistry (Illumina).

Raw image files were converted to fastq files using bcl2fastq (v2.20.0.422; Illumina). The fastq files were trimmed of adapter sequences, quality-filtered for a minimum base quality score of 20, and mapped against the P. vivax SaI I reference genome (assembly ASM241v2) using HISAT2 (version 2.0.5) (59). HISAT2 default settings were used with unpaired and discordant alignments suppressed. The number of reads per gene locus was obtained from the aligned BAM files using HTSeq-count (version 0.9.1) (60). A counts matrix was generated using a custom Perl script and then used for differential gene expression analysis. Read data normalization and differential expression were obtained using the Bioconductor package DESeq2 (version 3.4.1) (61).

An additional test for differential transcript expression (for edgeR) used the RSEM package (62) to map reads to the P. vivax Sal I strain from version 35 of PlasmoDB (40) using the Bowtie2 aligner. The results for read counts, reads per kilobase million, and transcripts per million for each transcript were mapped to an Excel spreadsheet. Statistical analysis was done using the edgeR program, taking as input the read count data (63).

To reduce possible confounding effects due to differences in the parasite stages, the data were adjusted using the RUVg method of the R package RUV-seq (43). Approximately 162 up-regulated and 146 down-regulated differentially expressed genes in Saimiri-infected samples relative to Aotus-infected samples were identified using a k value of 1, a log2 fold change >1.0 or <−1.0, and a false discovery rate-corrected P value <0.05.

Variant Detection.

Duplicate reads were marked in the aligned BAM files using Picard MarkDuplicates, 2.18.7-SNAPSHOT. To call variants in regions with similar coverage across all of the samples, a BED file of gene regions with greater than sixfold coverage was created from the aligned BAM files using bedtools v2.26.0. Next, SNP detection was performed for each sample using the BED region list and SAMtools v1.8 mpileup and bcftools call tools v1.8 (42) with the following parameters: –max-depth 5,000–skip-indels –ploidy 1. Variants were filtered for a minimum read depth of six using the vcfutils.pl varFilter tool. No variants were detected in AMA1, DBP, or MSP1 using this method. Furthermore, visual inspection of the reads aligned to the AMA1, DBP, and MSP1 genes using the IGV showed no differences between the samples or to the reference sequence.

qRT-PCR Validation.

The qRT-PCR validation was performed for eight P. vivax genes. The qRT-PCR probes and primer sets were designed using Primer Express version 3.0 (Life Technologies) (SI Appendix, Table S5). The qRT-PCR data were analyzed using ABI 7900HT version 2.4 sequence detection system software (Life Technologies). Since most of the eight genes had multiple paralogs in P. vivax, nonhomologous gene sequences were used for the primer and probe design. The GST gene was selected as a reference due to the low coefficient of variation across the sample set. Eight primer and probe sets run in dual plex with GST gene qRT-PCR primers all had 87% or higher amplification efficiency. The bar graph representing the qRT-PCR data from the normalized signal values was based on the average of two Aotus or two Saimiri samples. The error bar is based on the SD. Normalized next-generation sequencing values were correlated using Spearman rank to qRT-PCR values (GraphPad Prism 7.01).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Thomas E. Wellems (NIH), Susan K. Pierce (NIH), and David Serre (University of Maryland) for valuable suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript; Dr. Katie Bradwell (University of Maryland) for help in initial data analysis; Daniel E. Sturdevant (NIH) for advice on data analysis; and Anita Mora (NIH) for preparing the figure files. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The RNA sequencing data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE125284).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1818485116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH, Rothman IK. Erythrocyte receptors for (Plasmodium knowlesi) malaria: Duffy blood group determinants. Science. 1975;189:561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1145213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wertheimer SP, Barnwell JW. Plasmodium vivax interaction with the human Duffy blood group glycoprotein: Identification of a parasite receptor-like protein. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:340–350. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitnis CE, Miller LH. Identification of the erythrocyte binding domains of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi proteins involved in erythrocyte invasion. J Exp Med. 1994;180:497–506. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh K, et al. Malaria vaccine candidate based on Duffy-binding protein elicits strain transcending functional antibodies in a phase I trial. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:48. doi: 10.1038/s41541-018-0083-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tournamille C, Colin Y, Cartron JP, Le Van Kim C. Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;10:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howes RE, et al. The global distribution of the Duffy blood group. Nat Commun. 2011;2:266. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan JR, et al. Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a duffy antigen negative population in Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ménard D, et al. Plasmodium vivax clinical malaria is commonly observed in Duffy-negative Malagasy people. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5967–5971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wurtz N, et al. Vivax malaria in Mauritania includes infection of a Duffy-negative individual. Malar J. 2011;10:336. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fru-Cho J, et al. Molecular typing reveals substantial Plasmodium vivax infection in asymptomatic adults in a rural area of Cameroon. Malar J. 2014;13:170. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngassa Mbenda HG, Das A. Molecular evidence of Plasmodium vivax mono and mixed malaria parasite infections in Duffy-negative native Cameroonians. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niangaly A, et al. Plasmodium vivax infections over 3 years in Duffy blood group negative Malians in Bandiagara, Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:744–752. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo E, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria among Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative populations in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2015;14:84. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0596-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendes C, et al. Duffy negative antigen is no longer a barrier to Plasmodium vivax–Molecular evidences from the African West Coast (Angola and Equatorial Guinea) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunalan K, et al. Role of Plasmodium vivax Duffy-binding protein 1 in invasion of Duffy-null Africans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:6271–6276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606113113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poirier P, et al. The hide and seek of Plasmodium vivax in West Africa: Report from a large-scale study in Beninese asymptomatic subjects. Malar J. 2016;15:570. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1620-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelraheem MH, Albsheer MM, Mohamed HS, Amin M, Mahdi Abdel Hamid M. Transmission of Plasmodium vivax in Duffy-negative individuals in central Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:258–260. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trw014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asua V, et al. Plasmodium species infecting children presenting with malaria in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:753–757. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russo G, et al. Molecular evidence of Plasmodium vivax infection in Duffy negative symptomatic individuals from Dschang, West Cameroon. Malar J. 2017;16:74. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1722-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brazeau NF, et al. Plasmodium vivax infections in Duffy-negative individuals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:1128–1133. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunalan K, Niangaly A, Thera MA, Doumbo OK, Miller LH. Plasmodium vivax infections of Duffy-negative erythrocytes: Historically undetected or a recent adaptation? Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niang M, et al. Asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax infections among Duffy-negative population in Kedougou, Senegal. Trop Med Health. 2018;46:45. doi: 10.1186/s41182-018-0128-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menard D, et al. Whole genome sequencing of field isolates reveals a common duplication of the Duffy binding protein gene in Malagasy Plasmodium vivax strains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson RD, et al. Genomic analysis of local variation and recent evolution in Plasmodium vivax. Nat Genet. 2016;48:959–964. doi: 10.1038/ng.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ntumngia FB, et al. A novel erythrocyte binding protein of Plasmodium vivax suggests an alternate invasion pathway into Duffy-positive reticulocytes. MBio. 2016;7:e01261-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01261-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roesch C, et al. Genetic diversity in two Plasmodium vivax protein ligands for reticulocyte invasion. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douglas NM, et al. Plasmodium vivax recurrence following falciparum and mixed species malaria: Risk factors and effect of antimalarial kinetics. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:612–620. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas NM, et al. Mortality attributable to Plasmodium vivax malaria: A clinical audit from Papua, Indonesia. BMC Med. 2014;12:217. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochar DK, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria: A report on serial cases from Bikaner in northwestern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber BE, et al. Parasite biomass-related inflammation, endothelial activation, microvascular dysfunction and disease severity in vivax malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004558. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran TM, et al. Detection of a Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte binding protein by flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2005;63:59–66. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins WE, Contacos PG, Krotoski WA, Howard WA. Transmission of four Central American strains of Plasmodium vivax from monkey to man. J Parasitol. 1972;58:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell CC, Collins WE, Chin W, Roberts JM, Broderson JR. Studies of the Sal I strain of Plasmodium vivax in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) J Parasitol. 1983;69:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hester J, et al. De novo assembly of a field isolate genome reveals novel Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte invasion genes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auburn S, et al. A new Plasmodium vivax reference sequence with improved assembly of the subtelomeres reveals an abundance of pir genes. Wellcome Open Res. 2016;1:4. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.9876.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tournamille C, et al. Sequence, evolution and ligand binding properties of mammalian Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:682–694. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0633-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichols ME, Rubinstein P, Barnwell J, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Rosenfield RE. A new human Duffy blood group specificity defined by a murine monoclonal antibody. Immunogenetics and association with susceptibility to Plasmodium vivax. J Exp Med. 1987;166:776–785. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.3.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chitnis CE, Chaudhuri A, Horuk R, Pogo AO, Miller LH. The domain on the Duffy blood group antigen for binding Plasmodium vivax and P. knowlesi malarial parasites to erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1531–1536. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aurrecoechea C, et al. PlasmoDB: A functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539–D543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlton JM, et al. Comparative genomics of the neglected human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nature. 2008;455:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nature07327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Risso D, Ngai J, Speed TP, Dudoit S. Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:896–902. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunalan K, Gao X, Yap SS, Huang X, Preiser PR. The role of the reticulocyte-binding-like protein homologues of Plasmodium in erythrocyte sensing and invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:35–44. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang J, Barnwell JW, Meyer EV, Galinski MR. Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-3 (PvMSP3): Expression of an 11 member multigene family in blood-stage parasites. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyagi RK, Sharma YD. Erythrocyte binding activity displayed by a selective group of Plasmodium vivax tryptophan rich antigens is inhibited by patients’ antibodies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeeshan M, Tyagi RK, Tyagi K, Alam MS, Sharma YD. Host-parasite interaction: Selective Pv-fam-a family proteins of Plasmodium vivax bind to a restricted number of human erythrocyte receptors. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1111–1120. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyagi K, et al. Plasmodium vivax tryptophan rich antigen PvTRAg36.6 interacts with PvETRAMP and PvTRAg56.6 interacts with PvMSP7 during erythrocytic stages of the parasite. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alam MS, et al. Interaction of Plasmodium vivax tryptophan-rich antigen PvTRAg38 with band 3 on human erythrocyte surface facilitates parasite growth. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20257–20272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.644906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alam MS, Rathore S, Tyagi RK, Sharma YD. Host-parasite interaction: Multiple sites in the Plasmodium vivax tryptophan-rich antigen PvTRAg38 interact with the erythrocyte receptor band 3. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:232–241. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rathore S, et al. Basigin interacts with Plasmodium vivax tryptophan-rich antigen PvTRAg38 as a second erythrocyte receptor to promote parasite growth. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:462–476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alam MS, Zeeshan M, Rathore S, Sharma YD. Multiple Plasmodium vivax proteins of Pv-fam-a family interact with human erythrocyte receptor Band 3 and have a role in red cell invasion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1211–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venkatesh A, et al. Identification of highly expressed Plasmodium vivax proteins from clinical isolates using proteomics. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2017;12:e1700046. doi: 10.1002/prca.201700046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernabeu M, et al. Functional analysis of Plasmodium vivax VIR proteins reveals different subcellular localizations and cytoadherence to the ICAM-1 endothelial receptor. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:386–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnwell JW, Howard RJ, Miller LH. Altered expression of Plasmodium knowlesi variant antigen on the erythrocyte membrane in splenectomized rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1982;128:224–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnwell JW, Howard RJ, Miller LH. Influence of the spleen on the expression of surface antigens on parasitized erythrocytes. Ciba Found Symp. 1983;94:117–136. doi: 10.1002/9780470715444.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.David PH, Hommel M, Miller LH, Udeinya IJ, Oligino LD. Parasite sequestration in Plasmodium falciparum malaria: Spleen and antibody modulation of cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5075–5079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Research Council . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;4:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.