Abstract

Aim:

The present study analyzed the clinical significance of duration of intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) associated with increased serum lactate in critically ill patients with severe sepsis.

Materials and Methods:

Our study was an observational, prospective study carried out in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at J.L.N Medical College, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India. In our study, we included a total of 100 patients and intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) was measured through intravesical route at the time of admission and after 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h via a urinary catheter filled with 25 ml of saline. Duration of ICU and hospital stay, need for ventilator support, initiation of enteral feeding, serum lactate level at time of admission and after 48 h, and 30-day mortality were noted as outcomes.

Results:

In our study, an overall incidence of IAH was 60%. Patients with cardiovascular surgery and renal and pulmonary dysfunction were 93.3%, 55%, and 60%, respectively, at the time of admission and 65%, 10%, and 10%, respectively, after 72 h of admission in the surgical ICU. Nonsurvivors had statistically significant higher IAP and serum lactate levels than survivors. Patients with longer duration of IAH had longer ICU and hospital stay, longer duration of vasopressors and ventilator support, and delayed enteral feeding.

Conclusion:

There is a strong relationship “risk accumulation” between duration of IAH associated with increased serum lactate and organ dysfunction. The duration of IAH was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality. Early recognition and prompt intervention for IAH and severe sepsis are essential to improve the patient outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Abdominal compartment syndrome, intra-abdominal hypertension, serum lactate level, severe sepsis

INTRODUCTION

The effect of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) on various organ systems has been studied over the past century. Normally, the average IAP is about 0 mmHg, and some physiological states such as morbid obesity (body mass index >32 kg/m2) or pregnancy can cause a chronic increase in IAP with no significant or mild pathophysiological consequences. Emerson first noted the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with elevated IAP in 1911.[1]

IAP is the pressure within the abdominal cavity bounded by abdominal muscles and diaphragm. It is affected by body weight, posture, tension of abdominal muscles, and movement of the diaphragm. Although IAP can physiologically reach the elevated values transiently up to 80 mmHg (Valsalva maneuver, cough, weight lifting, etc.,), these values cannot be tolerated for long periods. In the critically ill, IAP is often increased, and also, abdominal surgery, bacterial translocation, sepsis, endotoxemia, organ failure, and mechanical ventilation are associated with an increase in IAP.

The range of IAP in the critically ill is between 5 and 7 mmHg. According to the definition of the World Society for Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS), intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) is a continuous increase in the IAP above 12 mmHg that is recorded in at least two measurements at the intervals of 1–6 h[2] whereas ACS is defined as “sustained IAP >20 mmHg (with or without an abdominal perfusion pressure <60 mmHg) that is associated with new organ dysfunction/failure.[3] Clinical conditions that increase IAH include blood and ascites in the peritoneal cavity, bowel distension and edema, high volume resuscitation and massive transfusion, damage control surgery in traumatic patients, excessive tension after abdominal closure, postoperative ileus, eschar in burn patients, and hemodilution.

IAH above 12 mmHg compromises the regional blood flow and reduces the splanchnic tissue perfusion, thus producing tissue hypoxia, intestinal swelling, and dysfunction of other organs. The IAH progression leads to ACS. A variety of dysfunctions are triggered, including bowel microcirculation dysfunction, loss of intestinal barrier, retroperitoneal and visceral edema, as well as induction of severe inflammatory response, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and multiorgan dysfunction syndrome.

Serum lactate level was considered normal up to 18.2 mg/dl. Hyperlactacidemia is a clinical marker of underlying ischemia and/or hypoxia whose degree of increase correlates with the severity of the illness. The plasma lactate is used to detect and monitor hypoperfusion and as a prognostic indicator. Lactate production may be considered as an indicator of protective response by the body to allow cellular energy production to continue when tissue oxygen supply is inadequate for aerobic metabolism. The hypoxia-inducible factor is the sensor of low tissue oxygen that switches metabolism to anaerobic mode. The increase in plasma lactate concentration may develop due to an absolute and/or relative tissue oxygen deficiency.[4]

Aims and objectives

To investigate the influence of IAH development and its duration associated with increased serum lactate on the clinical course and outcome of critically ill surgical patients

To assess whether IAH at admission was an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality

To determine the epidemiology and outcomes of IAH duration in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective, observational study was conducted on patients admitted to the surgical ICU in the Department of General Surgery, J.L.N. Medical College and Hospitals, Ajmer, from January 2016 to December 2017.

Following cases were considered eligible for inclusion in the study:

Age >12 years

Patients who were admitted for blood and ascites in the peritoneal cavity, bowel distension and edema, high volume resuscitation and massive transfusion, damage control surgery in traumatic patients, excessive tension after abdominal closure, postoperative ileus, eschar in burn patients, and hemodilution with severe sepsis were enrolled within 24 h of admission to the ICU

Able to lie supine.

Following cases were excluded from the study:

Pregnant females

Patients in whom Foley's catheterization was not possible

Therapeutic open abdomen.

Severe sepsis is defined as “failure of more than one organ systems due to sepsis, an arterial blood lactate concentration more than 18.2 mg/dl or hypotension (with a systolic blood pressure <90 mm of Hg)”.

Septic shock requires the presence of the above, associated with more significant evidence of tissue hypoperfusion and systemic hypotension.

Methods

This study included 100 patients who were admitted to the ICU within 24 h of admission. IAP was measured for every patient pre- and post-operatively at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h.

Parameters noted

Parameters noted were BP, respiratory rate, SpO2, urine output, blood urea, serum creatinine, IAP, duration of ICU stay, duration of hospital stay, need for ventilator support, duration of ventilator support, serum lactate level (at time of admission and after 48 h), morbidity (wound dehiscence, wound sepsis, burst abdomen, and relaparotomy), and mortality in 30 days.

Measurement of intra-abdominal pressure

The abdominal pressure was indirectly determined by measuring urinary bladder pressure by a Foley's catheter. The bladder was drained and then filled with 25 ml of sterile saline through the Foley's catheter. The tubing of the collecting bag was clamped. The catheter was connected to a saline manometer. The anterior superior iliac spine was taken the zero reference and the pressure measured in cm of water at the end of expiration. A conversion factor of 1.36 was used to convert pressure into mmHg.

Interpretation

Grading of IAP is as follows; Grade 1: (12–15 mmHg), Grade 2: (16–20 mmHg), Grade 3: (21–25 mmHg), and Grade 4: (>25 mmHg).

The term “ACS” was used when IAP >20 mmHg and associated with at least one newly developed organ system dysfunction.

The data were analyzed and calculated in terms of mean, standard deviation, and percentage. Mean IAP was calculated at various intervals for the study population, and its effects were seen in terms of various morbidities and mortality.

RESULTS

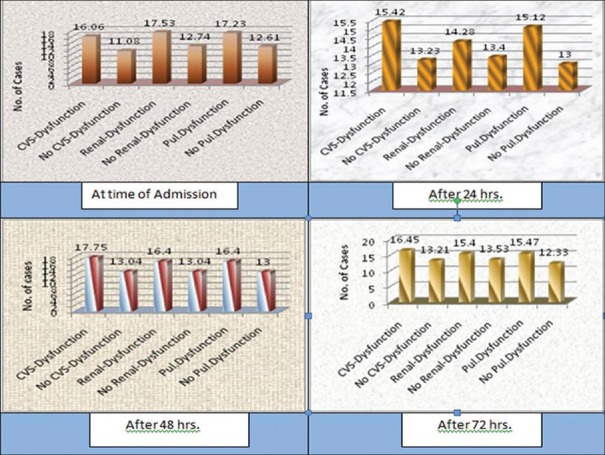

A total of 100 patients were included in this study. Out of these, there were 74 males and 26 females (M:F = 3:1). Various indications for ICU admission were perforation peritonitis (50%), intestinal obstruction (17%), blunt trauma abdomen (19%), and others (14%) (burn, ascites, etc.) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Various indications for Intensive Care Unit admission

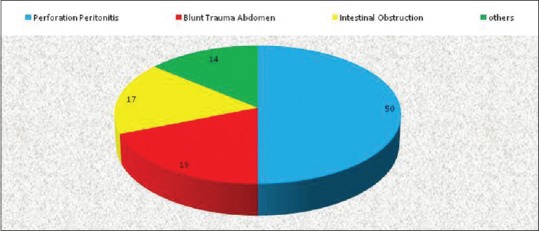

Sixty percent of the patients presented with IAH while 40% of the patients presented with IAP <12 mmHg out of 100 patients. Fifteen patients out of 60 developed IAH for 3 days and two patients for more than 10 days [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Distribution of patients by duration of intra-abdominal hypertension

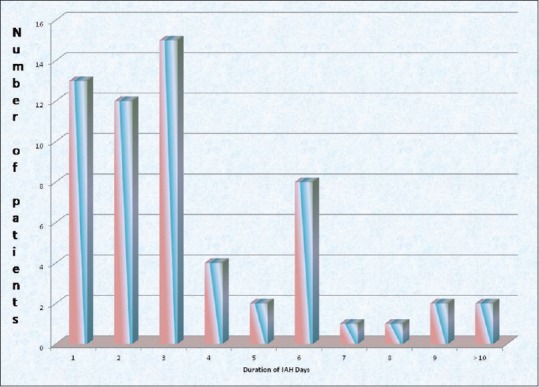

Mean IAP in cardiovascular surgery (CVS) dysfunction patients was 16.06, 15.42, 17.75, and 16.45 mmHg at the time of admission and after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, in contrast to non-CVS dysfunction patients being 11.08, 13.23, 13.04, and 13.21, respectively. Mean IAP in renal dysfunction patients was 17.53, 14.28, 16.4, and 15.4 mmHg at the time of admission and after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, in contrast to nonrenal dysfunction patients being 12.74, 13.4, 13.04, and 13.53, respectively. Mean IAP in pulmonary dysfunction patients was 17.23, 15.12, 16.4, and 15.47 mmHg at the time of admission and after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, in contrast to nonpulmonary dysfunction patients being 12.61, 13, 13, and 12.33, respectively [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Mean intra-abdominal pressure in Intensive Care Unit patients after admission and 24, 48, and 72 h with their effect on various systems

In our study, mean age of patients in survivor group was 50.04 years and in nonsurvivors was 55.5 years. Mean duration of IAH was 2.85 days in survivors and was 8.38 days in nonsurvivor group of patients. Mean serum lactate level was 46.785 mg/dl at the time of admission and 21.02 mg/dl after 48 h in survivors as compared to nonsurvivors which showed 72.59 mg/dl and 73.68 mg/dl at the time of admission and after 48 h, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of survivors and nonsurvivors

| Variable | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | n=92 | n=8 | 0.3314 |

| 50.04±14.9 | 55.5±18.31 | ||

| Duration of IAH (days) | n=52 | n=8 | <0.001 |

| 2.85±1.78 | 8.38±3.5 | ||

| Serum lactate level (mg/dl) | |||

| At admission | n=92 | n=8 | 0.0001 |

| 46.785±14.184 | 72.59±7.6 | ||

| After 48 h | 21.02±3.69 | 73.68±5.38 | 0.0001 |

IAH: Intra-abdominal hypertension

In our study, mean age of patients in IAH group was 53.67 years and in non-IAH group was 45.7 years. Mean fluid intake in IAH group patients was 4166.67, 4116.67, and 4065.67 ml on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and in non-IAH group patients was 2830, 2812.5, and 2817.5 ml on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Mean urine output in IAH group patients was 885, 1328.83, and 1490.83 ml on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and in non-IAH group was 1463.25, 1345, and 1990 ml on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Mean blood urea level in the IAH group patients was 54.407 mg/dl and in non-IAH group was 26.538 mg/dl. Similarly, serum creatinine level was 1.3 mg/dl in IAH group patients and 0.823 mg/dl in non-IAH group patients (normal range of serum creatinine in our institute laboratory was 0.9–1.2 mg/dl). Mean serum lactate level in IAH group patients was 46.785 and 28.833 mg/dl at time of admission and after 48 h; similarly, in non-IAH group patients, mean serum lactate level was 22.96 and 16.70 mg/dl at the time of admission and 48 h, respectively. In IAH group patients, mean pulse rate was 107.73, 105.97, and 102.57 per minute on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In non-IAH group patients, mean pulse rate was 84.9, 82.4, and 81.1 per minute on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Mean BP in IAH group patients was 89.37, 93.17, and 94.87 mmHg on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Mean BP in non-IAH group patients was 105.05, 110.65, and 113.05 mmHg on day 1, 2, and 3, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in our study

| Variables | IAH group | Non-IAH group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.67±14.46 | 45.7±15.11 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 45 | 29 | |

| Female | 15 | 11 | |

| Total fluid intake (ml/day) | |||

| Day 1 | 4166.67±559.86 | 2830±80.03 | <0.0001 |

| Day 2 | 4116.67±517.55 | 2812.5±72.48 | <0.0001 |

| Day 3 | 4065.67±479.7 | 2817.5±63.6 | <0.0001 |

| Urine output (ml/day) | |||

| Day 1 | 885±388.75 | 1463.25±262.28 | <0.0001 |

| Day 2 | 1328.83±527.32 | 1345±207.49 | <0.0001 |

| Day 3 | 1490.83±560.83 | 1990±212.19 | <0.0001 |

| Blood urea (mg %) | 54.407±35.067 | 26.538±16.295 | <0.0001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg %) | 1.3030±0.579 | 0.823±0.214 | <0.0001 |

| Serum lactate (mg/dl) | |||

| At admission | 46.785±14.184 | 22.96±3.017 | <0.0001 |

| After 48 h | 28.833±18.167 | 16.705±2.513 | <0.0001 |

| Pulse rate (per min) | |||

| Day 1 | 107.73±10.74 | 84.90±6.61 | <0.0001 |

| Day 2 | 105.97±12.04 | 82.4±4.92 | <0.0001 |

| Day 3 | 102.57±13.42 | 81.1±4.12 | <0.0001 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||

| Day 1 | 89.37±8.3 | 105.05±9.22 | <0.0001 |

| Day 2 | 93.17±7.86 | 110.65±7.2 | <0.0001 |

| Day 3 | 94.87±10.98 | 113.05±7.0 | <0.0001 |

BP: Blood pressure, IAH: Intra-abdominal hypertension

In our study, mean length of ICU stay in IAH group patients was 4.6 days as compared to non-IAH group patients who showed 0.10 days ICU stay. Mean length of hospital stay was 10.98 days in IAH group and 8.15 days in non-IAH group patients. Mean duration of ventilator support was 2.12 days in IAH group and 0.10 days in non-IAH group patients. Mean duration of vasopressor support was 5.24 days in IAH group and 1.0 days in non-IAH group patients. Start of enteral feeding in IAH group patients was after 8.35 days as compared to 5.28 days in non-IAH group patients. Mechanical ventilation needed in 36 patients in IAH group and death of eight patients also occurred in IAH group patients [Table 3].

Table 3.

Clinical outcome according to intra-abdominal hypertension

| Variables | IAH group | Non-IAH group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 4.6±2.86 | 0.10±0.30 | 0.0001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 10.98±3.07 | 8.15±1.39 | 0.0061 |

| Duration of ventilatory support (days) | 2.12±3.01 | 0.10±0.30 | 0.04 |

| Duration of vassopressor support (days) | 5.24±2.65 | 1.00 | 0.0289 |

| Start of enteral feeding (days) | 8.35±1.93 | 5.28±1.11 | <0.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilation (n) | 36 | 0 | |

| 30-day mortality (n) | 8 | 0 |

IAH: Intra-abdominal hypertension, ICU: Intensive Care Unit

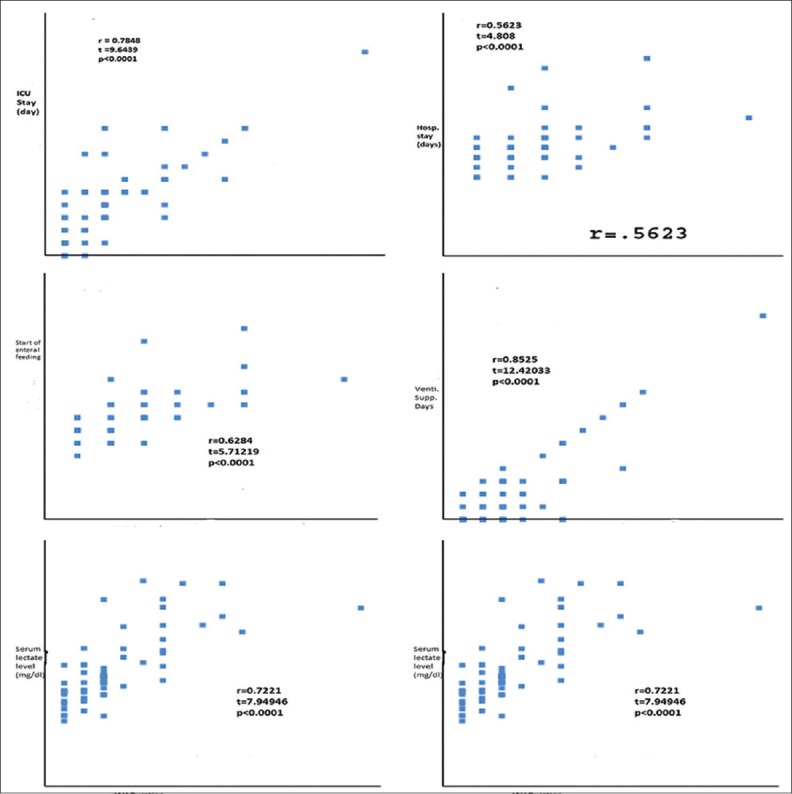

In our study, patients who had longer duration of IAH showed longer ICU stay (r = 0.7848) and similarly showed longer hospital stay (r = 0.5623). Patients who showed longer duration of IAH needed longer duration of vasopressor support (r = 0.7610) and longer duration of mechanical support (r = 0.8525). Start of enteral feeding was also delayed in longer duration of IAH group patients (r = 0.6284). Serum lactate level was high in longer duration of IAH group patients at the time of admission (r = 0.7221) and after 48 h (r = 0.6812) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Clinical effects of the duration of intra-abdominal hypertension

DISCUSSION

Our study population was a group of patients who were admitted to the ICU for various indications and included traumatic as well as nontraumatic patients. There were 74% males and 26% females. A similar ratio was seen in the studies by Khan et al. (76% males), Kyoung and Hong (76% males), Daga et al. (76% males), and Abdelkalik et al. (65% males).[5,6,7,8] The mean age of the patients in our study was 51.11 ± 14.79 years. Incidence of IAH was 60% in our study and Maddison et al. showed 39% of IAH incidence.[9] Out of 100 patients, there were 19% blunt trauma patients in the study by Khan et al. (19%), and Daga et al. (14%) also had similar number of trauma patients;[5,7] this is in contrast to the study by Cheatham et al., who had 68% of trauma patients in their study group.[3] This can be explained by the population selected for the study. Arabadzhiev et al. examined 240 ICU patients divided into three groups (patients submitted to elective surgery, emergency surgery, and medical patients). In the elective surgery group, there was 12.5% IAH, while in the emergency group, IAH was 43.75%, and in the medical patients, it was 42.5%.[10]

The number of patients in IAH group at the time of admission in ICU was 60 patients; after 24 h – 55 patients, after 48 h – 47 patients, and after 72 h – 36 patients. This can be explained by the observation that in our study, 67% of the patients had perforation peritonitis and intestinal obstruction, leading to elevated IAP which after decompression and removal of several liters of fluid and gases returns to normal level.

We observed that in IAH group patients, mean respiratory rate, daily fluid intake, blood urea level, and daily mean pulse rate were statistically significantly higher as compared to non-IAH group patients. Similarly, in IAH group patients, mean daily urine output, mean daily BP, and mean serum creatinine level were statistically significantly low as compared to non-IAH group patients.

In our study, mean serum lactate level in patients of IAH group at the time of admission was 46.785 ± 14.184 mg/dl and after 48 h was 28.833 ± 18.167 mg/dl as compared to non-IAH group patients which showed mean serum lactate level being 22.96 ± 3.017 mg/dl and 16.705 ± 2.513 mg/dl at the time of admission and after 48 h, respectively. It shows that patients who had IAH also had increased serum lactate level. In IAH group patients who had mean serum lactate level >36.4 mg/dl at the time of admission, their mean ICU stay was 4.25 days, mean hospital stay was 12.03 days, and start of enteral feeding after 8.78 days. In the same group patients who had mean serum lactate level <36.4 mg/dl at time of admission, their mean ICU stay was 2.17 days, mean hospital stay was 9.25 days, and start of enteral feeding was after 6.91 days. The results showed that patients who had higher serum lactate level at the time of admission showed longer ICU stay, longer hospital stay, and delayed enteral feeding. Similar results had also viewed in case of mechanical ventilation and vasopressor duration. Similarly, mean serum lactate level was statistically significantly higher in patients of nonsurvivor group as compared to survivors. Nonsurvivors showed mean serum lactate level of 72.9 mg/dl and 73.7 mg/dl at the time of admission and after 48 h, respectively. Similarly, nonsurvivors showed mean ICU stay of 8.38 days, mean hospital stay of 8.38 days, longer mechanical ventilation, and longer vasopressor support. Patients having severe sepsis showed higher value of serum lactate, so high serum lactate level is strongly associated with morbidity and mortality. Vincent et al. concluded that the observation of a better outcome associated with decreasing blood lactate concentrations was consistent throughout the clinical studies and was not limited to septic patients.[11] The third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock also includes having a serum lactate level >2 mmol/L after adequate fluid resuscitation in septic shock definition, in this issue of Journal of the American Medical Association.[12] Thus, a serum lactate level >2 mmol/L may be a new emerging vital sign of septic shock. Importantly, serum lactate level can be greatly increased under conditions of low BP requiring vasopressors because vasopressors constrict vessels resulting in tissue hypoxia. Based on this pathophysiology, new definition of septic shock can be explained although serum lactate level of 2 mmol/L (18.2 mg/dL) is normal value. Therefore, if a patient has a serum lactate level >2 mmol/L, BP or serum lactate level should be carefully monitored.[13] Resuscitation of the critically ill patients should be aimed at the reversal of tissue hypoxia. The use of lactate as a hemodynamic marker and resuscitation end point makes physiologic sense and is supported by the recent data. The use of lactate clearance versus other traditional end points of resuscitation, such as mixed venous oxygen saturation, should be based on the clinical characteristics and response of the individual patient.[14] Kovac et al. concluded that peritoneal drainage fluid lactate may be an early sign of IAH-induced pathology than plasma lactate.[4]

Our study showed that mean age of the survivors was 50.04 years and nonsurvivors was 55.5 years, whereas Malbrain et al. showed that mean age of survivors 64 years and nonsurvivors 67 years.[15]

We observed that the mean IAP at various intervals in patients having organ dysfunctions was high as compared to without organ dysfunctions. In the subgroup of patients with IAH at admission, associated CVS dysfunction was seen in 63 patients and elevated IAP was found to have detrimental effect on pulse rate and BP. After 24 h, 55 patients had CVS dysfunction, after 48 h – fifty patients had CVS dysfunction, and after 72 h – forty patients had CVS dysfunction. It suggests that significant improvement in CVS function occurred after decompression [Figure 3].

Renal dysfunction was seen in 34 patients at the time of admission, 25 patients after 24 h, 10 patients after 48 h, and 10 patients after 72 h, and elevated IAP was found to have detrimental effect on blood urea, serum creatinine, and urine output. After intervention, significant improvement in renal function was seen [Figure 3].

Pulmonary dysfunction was seen in 38 patients at the time of admission, 25 patients after 24 h, 20 patients after 48 h, and 10 patients after 72 h, and elevated IAP was found to have detrimental effect on respiratory rate and SPO2 level and need high PEEP (more than 2 cm of water) after intervention significant improvement in pulmonary function was seen [Figure 3].

This study was to observe the clinical effect of time dependence of IAH. The effect of IAH in organ dysfunction involves a myriad of pathologic changes. There was significant improvement seen in CVS and renal and pulmonary systems following interventions in patients who had IAH at the time of admission with organ system derangements.

Mean IAP was high in patients having organ system dysfunction as compared to without having organ system dysfunction. In our study, we observed that 40 patients did not have IAH, 69 patients underwent laparotomy in which 47 patients belonged to IAH group and 22 were in non-IAH group. Remaining 31 were nonlaparotomy patients in which 13 patients from IAH group and 18 patients from non-IAH group. Tiwari et al. showed that laparotomy was done in 53% and no laparotomy in 47% of their patients.[16] Forty patients developed IAH for 3 days and 20 patients developed IAH for more than 3 days. Eight patients showed 30-day mortality that had IAH for more than 3 days (13.3%) in contrast to the study by Abdelkalik et al., in which mortality was 39% in IAH group patients.[8] Duration of IAH in survivors was 2.85 days and in nonsurvivors was 8.38 days. It suggests that duration of IAH was more significant predictor for morbidity and mortality than the development of IAH. Most of the previous studies have focused on the effect of IAH. However, the duration of IAH is more important as an outcome prognostic factor than a just presence of IAH; it could be explained that prolonged IAH would accumulate risk for organ failure and worsen the outcomes.

We observed that patients having longer IAH duration showed prolonged hospital stay, longer ICU stay, longer duration of ventilator support, longer duration of vasopressor support, and delayed enteral feeding as compared to non-IAH group patients. This study identified the phenomenon that persistent IAH aggravated organ failure and increased mortality independently.

In addition to IAH development, sustained IAH reduced the chance of recovery and forced patients into a vicious cycle. The results of the present study showed that the IAH duration is a more important clinical factor than the development of IAH.

CONCLUSION

Raised IAP with increased serum lactate level associated with higher morbidity and mortality in patients who were admitted to the ICU. There is strong relationship “risk accumulation” between duration of IAH and organ dysfunction. Persistent elevation of IAH led to aggravating clinical outcomes including organ failure and mortality. Therefore, consistent vigil and more frequent monitoring of IAP and early recognition and prompt intervention for IAH and severe sepsis are essential to improve patient outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Emerson H. Intra-abdominal pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1911;7:754–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, Jaeschke R, Malbrain ML, De Keulenaer B, et al. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: Updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1190–206. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2906-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheatham ML, Malbrain ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J, et al. Results from the international conference of experts on intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome.II. Recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:951–62. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovac N, Širanović M, Perić M. Relavance of peritoneal drainage fluid lactate level in patients with intra-abdominal hypertension. Cogent Medicine. 2017;4:1308083. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan S, Verma AK, Ahmad SM, Ahmad R. Analyzing intra-abdominal pressures and outcomes in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:318–25. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyoung KH, Hong SK. The duration of intra-abdominal hypertension strongly predicts outcomes for the critically ill surgical patients: A prospective observational study. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daga S, Yerrapragada S, Chowdary AK, Satyanarayana G. Analyzing intra-abdominal pressures and outcomes in patients undergoing laparotomy. Int Surg J. 2017;4:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelkalik MA, Elewa GM, Kamaly AM, Elsharnouby NM. Incidence and prognostic significance of intra abdominal pressure in critically ill patients. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol. 2014;7:107–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddison L, Starkopf J, Reintam Blaser A. Mild to moderate intra-abdominal hypertension: Does it matter? World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5:96–102. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arabadzhiev GM, Tzaneva VG, Peeva KG. Intra-abdominal hypertension in the ICU – A prospective epidemiological study. Clujul Med. 2015;88:188–95. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vincent JL, Quintairos E Silva A, Couto L, Jr, Taccone FS. The value of blood lactate kinetics in critically ill patients: A systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1403-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: For the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:775–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SM, An WS. New clinical criteria for septic shock: Serum lactate level as new emerging vital sign. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1388–90. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.05.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller BM, Dellinger RP. Lactate as a hemodynamic marker in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:267–72. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283532b8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Cesana BM, Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Sugrue M, et al. A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis on intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients: The wake-up project. World initiative on abdominal hypertension epidemiology, a unifying project (WAKE-up!) Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:293–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwari AR, Pandya JS. Study of the occurrence of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome in patients of blunt abdominal trauma and its correlation with the clinical outcome in the above patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11:9. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]