Abstract

Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells play critical roles in autoimmune, anti-tumor and anti-microbial immune responses, and are activated by glycolipids presented by the MHC class I-like molecule, CD1d. How the activation of signaling pathways impacts antigen (Ag)-dependent iNKT cell activation is not well-known. In the current study, we found that the MAPK JNK2 not only negatively regulates CD1d-mediated Ag presentation in APCs, but also contributes to CD1d-independent iNKT cell activation. A deficiency in the JNK2 (but not JNK1) isoform enhanced Ag presentation by CD1d. Using a vaccinia virus (VV) infection model known to cause a loss in iNKT cells in a CD1d-independent, but IL-12-dependent manner, we found the virus-induced loss of iNKT cells in JNK2 KO mice was substantially lower than that observed in JNK1 KO or wildtype (WT) mice. Importantly, compared to WT mice, JNK2 KO mouse iNKT cells were found to express less surface IL-12 receptors. As with a VV infection, an IL-12 injection also resulted in a smaller decrease in JNK2 KO iNKT cells as compared to WT mice. Overall, our work strongly suggests JNK2 is a negative regulator of CD1d-mediated Ag presentation and contributes to IL-12-induced iNKT cell activation and loss during viral infections.

Keywords: Antigen Processing and Presentation, CD1d, Signal Transduction, Viral Infection, NKT Cells, Protein Kinases

Introduction

Lipid antigen (Ag) presentation by CD1d to natural killer T (NKT) cells is an important component of the innate immune system [1–4]. When NKT cells are activated by lipid-bound CD1d, they rapidly secrete both Th1 and Th2 cytokines [2]. CD1d-mediated Ag presentation to NKT cells is important in both innate anti-viral and anti-tumor immune responses [1, 5, 6].

Besides activation following cognate interactions with CD1d, type I NKT cells, also called invariant NKT (iNKT) cells can also be activated by cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-18 and type I interferons (IFNs) [7–9]. We and others have shown that IL-12 production during a microbial (e.g., virus or bacterium) infection is important for CD1d-independent iNKT cell activation [10–12]. In fact, microbial infections can trigger robust iNKT cell responses in the absence of antigenic stimulation [13]. iNKT cells activated by cytokines also display distinct phenotypes from those being activated by CD1d-dependent lipid Ag presentation [14]. In addition, a virus infection [10] and IL-12 [7, 9] can cause a reduction of iNKT cells in vivo, via activation-induced cell death. All of these observations demonstrate the complexity of iNKT cell activation during microbial infections.

Several viruses have been shown to inhibit CD1d-mediated Ag presentation through a variety of mechanisms [6, 15–20]; one mechanism is through the activation of cellular signaling pathways [21]. We have shown that vaccinia virus (VV) [6] and vesicular stomatitis virus [15] activate two mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), p38 and ERK, upon infection. It is through the activation of p38, at least in part, that these viruses inhibit Ag presentation by CD1d [6, 15]. The third family of MAPKs is the c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK), which can also be activated by a viral infection [22, 23]. JNKs are encoded by three different genes: JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3 [24]. JNK1 and JNK2 are ubiquitously expressed, whereas JNK3 expression is limited to brain, heart and testis [24]. It has been widely reported that JNK1 and JNK2 have distinct roles in different physiological responses and disease models [25–31]; in terms of the anti-viral immune response, JNK1 and JNK2 differentially control the fate of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during infection [32, 33].

JNK activation has been mostly investigated for its intrinsic role in conventional T cell development, activation and proliferation [24, 26, 34–36], although it has been demonstrated that JNK2, but not JNK1, controls naturally occurring T regulatory cells in an autonomous manner [26]. The importance of JNK in iNKT cell activation has not been investigated. In this report, we studied the role of JNK activation in regulating CD1d-mediated Ag presentation. In both non-infection and viral infection systems, we show that JNK2 is a negative regulator of Ag presentation by CD1d and further impacts virus-induced iNKT cell loss. Overall, our data strongly suggest that JNK2 has distinct roles in CD1d-dependent and -independent activation of iNKT cells.

Results

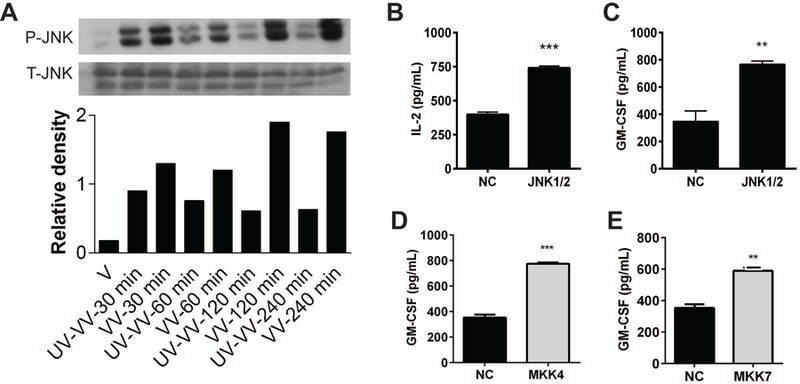

The JNK pathway is a negative regulator of CD1d-mediated Ag presentation

We have previously reported that live (but not UV-inactivated) VV inhibits CD1d-mediated Ag presentation [6, 17]. In the current study, we found that an infection with UV-inactivated VV was substantially less able to activate JNK as compared to live VV--particularly at longer infection times (Fig. 1A). Thus, we hypothesized that stimulation of the JNK pathway decreases CD1d-mediated Ag presentation following a VV infection. To test this hypothesis, CD1d+ cells were transfected with a shRNA plasmid specifically targeting both JNK1 and JNK2 expression. The resulting stable transfectants were co-cultured with NKT cells. Knocking down JNK1/2 expression in both mouse and human CD1d-expressing cells was associated with increased iNKT cell activation (Fig. 1B and 1C, respectively). Therefore, these data suggest that the JNK pathway is a negative regulator of CD1d-mediated Ag presentation.

Figure 1.

JNK negatively regulates CD1d-mediated Ag presentation. (A) LMTK-CD1d1 cells were infected with UV-inactivated VV or live VV for 4 h. The cells were lysed and the lysates were analyzed by Western blot using Abs specific for either phospho-JNK1/2 or total JNK1/2. The relative level of phospho-JNK to total JNK in each treatment is shown in the graph below the blot. (B) Murine LMTK-CD1d1 cells were transfected with plasmids containing a JNK1/2-targeting shRNA or a scrambled sequence for the negative control (NC). Stable transfectants were co-cultured with the mouse type II NKT cell hybridoma, N37–1A12, for 24 h. Culture supernatants were harvested and IL-2 production was measured by ELISA. Human HEK293-CD1d cells were transfected with plasmids containing shRNA specific for JNK1/2 (C), MKK4 (D) or MKK7 (E). Stable transfectants were co-cultured with human iNKT cells for 48 h. Culture supernatants were harvested and GM-CSF production was measured by ELISA. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

There are two MAPK kinases that are upstream of JNK: MKK4 and MKK7 [37, 38]. To further confirm the important role of the JNK pathway in regulating CD1d-mediated Ag presentation, we utilized MKK4- and MKK7-specific shRNA constructs to reduce their expression levels in CD1d+ cells. We observed that a decrease in either MKK4 or MKK7 expression enhanced CD1d-mediated Ag presentation, implying a role for both of these kinases in the control of Ag presentation by CD1d (Fig. 1D and 1E). Thus, these results further support the hypothesis that JNK pathway activation is inhibitory for CD1d-mediated Ag presentation.

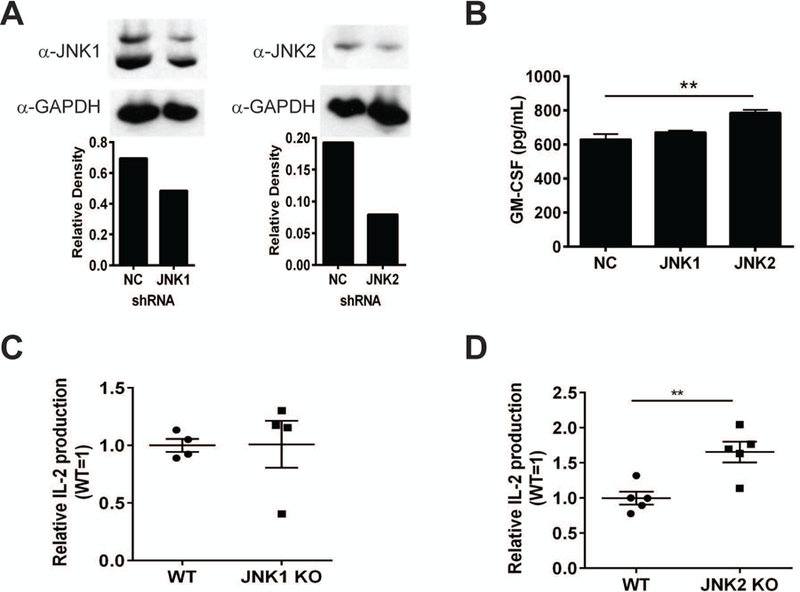

JNK2 (but not JNK1) regulates CD1d-mediated Ag presentation.

JNK1 and JNK2 have been widely studied and shown to have distinct functions in a number of mouse models [27–29, 31–33, 39]. To determine how JNK1 or JNK2 could individually impact CD1d-mediated Ag presentation, we generated JNK1- or JNK2-specific shRNA-expressing human CD1d+ cells. Knocking down JNK1 expression in HEK293-CD1d cells did not affect their ability to present Ag to NKT cells; however, reducing JNK2 expression in the same cells increased Ag presentation (Fig. 2A, 2B). This suggests that the activation of JNK2 (but not JNK1) impairs Ag presentation by CD1d. In a parallel analysis, bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were generated from JNK1- or JNK2-knockout (KO) mice and co-cultured with mouse NKT cells. We found that BMDCs from JNK1 KO mice could stimulate NKT cell as well as wildtype (WT; Fig. 2C). In contrast, JNK2 KO BMDCs were significantly better at activating NKT cells than WT (Fig. 2D). Therefore, these data support the hypothesis that JNK2 (but not JNK1) negatively regulates CD1d-mediated Ag presentation. It is worthwhile to point out that surface expression of CD1d on BMDCs was not affected by a JNK1 or JNK2 deficiency in either murine or human systems (Fig. S1A & S1B).

Figure 2.

JNK2 (but not JNK1) negatively regulates Ag presentation by CD1d. (A) HEK293-CD1d cells were transfected with plasmids containing JNK1 (left) or JNK2 (right) shRNA. Stable transfectants were lysed and analyzed by Western blot using a JNK1- or JNK2-specific mAb. HEK293-CD1d cells expressing scrambled shRNA (NC) were included as a control. The relative expression of JNK1 or JNK2 is shown in the graphs below the blots. (B) HEK293-CD1d cells expressing JNK1, JNK2 or NC shRNA were co-cultured with human iNKT cells for 48 h. Culture supernatants were harvested for measuring GM-CSF production by ELISA. BMDCs from JNK1 KO (C) or JNK2 KO (D) mice were co-cultured with the mouse type I NKT hybridoma N38–2C12 for 24 h. IL-2 production in the supernatants was measured by ELISA. (A-C) The data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments. The data shown in (D) are pooled from three independent experiments. Each dot represents an individual mouse, and plotted as mean ± SEM. **, p<0.01.

Reduced iNKT cell numbers in JNK2 (but not JNK1) knockout mice

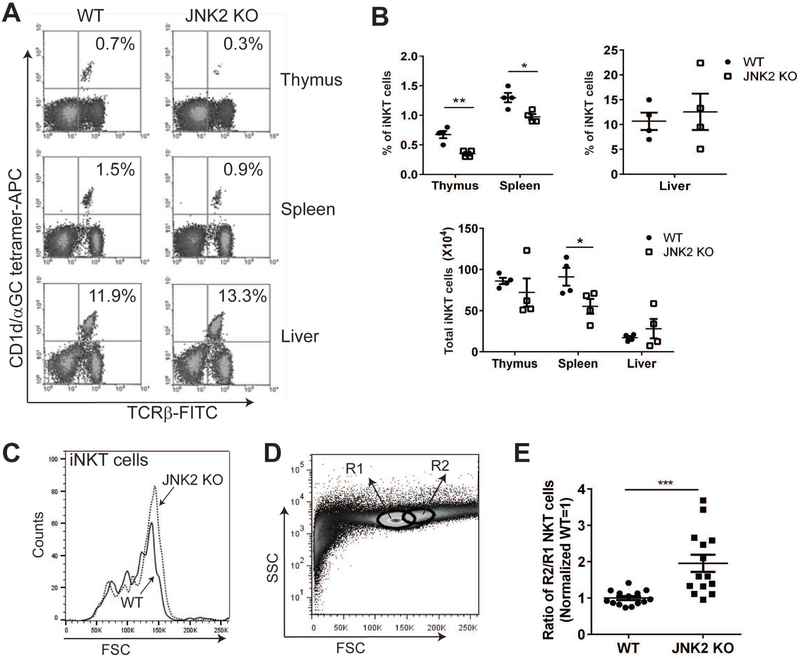

The function of CD1d is very important in the context of iNKT cell development and maturation. For example, it has been reported that abnormal CD1d expression or impaired CD1d-mediated Ag presentation often results in a defect in iNKT cell numbers and/or function in vivo [40, 41]. Because we found that the activation of JNK2 (but not JNK1) reduces CD1d-mediated Ag presentation in vitro, it was important to investigate whether there were any in vivo iNKT cell defects in JNK1- or JNK2-deficient mice. We found that JNK1 KO and WT mice had similar levels of iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen and liver (Fig. S2A and S2B); moreover, CD1d expression on splenic B cells from JNK1 KO mice was also similar to WT mice (Fig. S2C). By contrast, although there was not a difference in the liver, there was a significantly reduced number of iNKT cells in the thymi and spleens of JNK2 KO as compared to WT mice (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Reduced iNKT cell numbers in thymi and spleens of JNK2 KO mice. (A) Thymocytes, splenocytes and liver mononuclear cells from WT and JNK2 KO mice were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and a TCR-β-specific mAb for the identification of iNKT cells by flow cytometry. (B) The percentages (upper graphs) and total numbers (lower graph) of iNKT cells are shown for thymus, spleen and liver. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown. Each dot represents an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM. (C) Thymocytes from WT and JNK2 KO mice were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers. The cells that were detected with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers were gated and the forward scatter (FSC) is shown in the histogram. (D) The region 1 (R1) and R2 gating strategy of the thymocytes for (E) is shown. (E) Thymocytes from WT and JNK2 KO mice were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and a TCRβ-specific mAb for the identification of iNKT cells. The ratio of iNKT cells localized in the R2 gate relative to those in R1 was calculated and normalized (WT=1). Pooled data from three independent experiments are shown; each dot represents an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Interestingly, a further examination revealed that thymic iNKT cells in JNK2 KO mice were slightly larger via forward scatter analysis (Fig. 3C). Thymocytes were gated by the delineation of two different regions: Region 1 (R1) is where most thymocytes localized, whereas Region 2 (R2) is a small region to the right of R1 where cells of larger size are confined (Fig. 3D). We compared the percentage of iNKT cells that fell into these two different regions and found there were significantly more thymic iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice localized in R2 (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, cells from R2 actually expressed higher levels of annexin V (Fig. S3A & S3B), suggesting a more activated and apoptotic thymic iNKT cell population in JNK2 KO mice. We also analyzed CD69 and Annexin V staining on thymic iNKT cells, but did not observe any difference between JNK2 KO and their WT littermates (data not shown). In sum, our results show reduced iNKT cell numbers in JNK2 (but not JNK1) KO mice and that thymic iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice are larger than those from WT.

Double positive (DP) thymocytes are required for the positive selection of iNKT cells [42]. We found similar levels of CD1d expression on DP thymocytes from JNK2 KO mice compared to WT mice (Fig. S4A). Although there were fewer CD1dhi-expressing splenic B cells (MHC II+B220+), DCs (MHC II+CD11c+) and macrophages (MHC II+F4/80+) in JNK2 KO mice (Fig. S4B and S4C), the differences were not statistically significant. These results suggest that a JNK2-deficiency does not increase CD1d surface expression, further supporting the idea that enhanced CD1d-mediated Ag presentation in JNK2-deficient APCs is not due to increased CD1d expression.

We also examined different subsets of iNKT cells (i.e. NKT1/2/17 cells) [43] in the thymus and spleen. We found slight, but significantly reduced expression of T-bet in thymic iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice compared to those in WT mice (Fig.S4D), indicating a decrease in JNK2 KO NKT1 cells relative to WT; CD3+ thymic cells from both JNK2 KO and WT mice express similar levels of T-bet (Fig. S4D). No difference was observed regarding GATA-3 or RORγt expression in thymic iNKT cells, suggesting the NKT2 and NKT17 cells are normal in JNK2 KO mice (data not shown). Interestingly, both iNKT and conventional T cells from the spleens of JNK2 KO mice expressed lower levels of GATA-3 compared to WT (Fig.S4E). No difference was observed in terms of T-bet or RORγt expression in splenic iNKT or conventional T cells from JNK2 KO mice (data not shown). Taken together, our data suggest that enhanced CD1d-mediated Ag presentation in JNK2-deficient APCs may cause reduced development of NKT1 cells in the thymus.

JNK2 (but not JNK1) contributes to the VV-induced loss of iNKT cells.

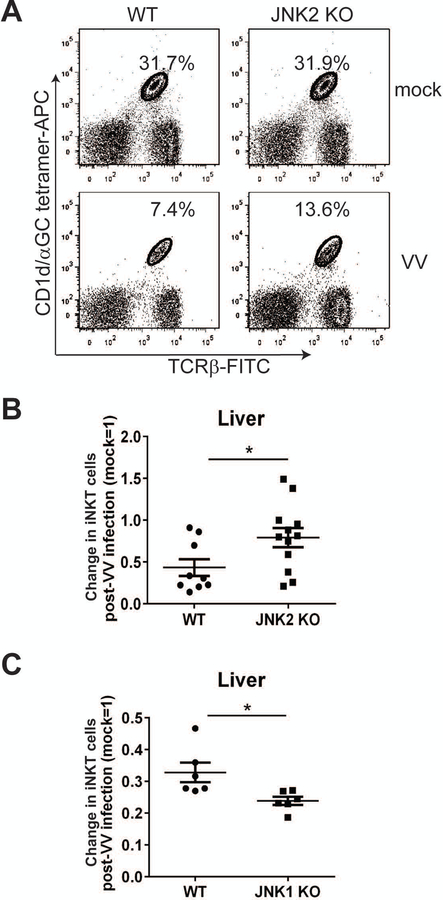

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that acute viral infections cause a decrease in iNKT cells in vivo [10, 44]. We next investigated whether a deficiency in JNK1 or JNK2 would impact this virus infection-induced loss. Prior reports indicated that JNK1 and JNK2 KO mice were comparable to WT mice in clearing viral infections [32, 33]. In a VV system, we also found that JNK1 and JNK2 KO mice were able to effectively control infection at WT levels (data not shown).A VV infection causes a reduction of iNKT cells in the liver and elsewhere [10]. When we compared JNK2 KO to WT mice, we found that the VV-induced loss in their liver iNKT cells was significantly less than in WT littermates (Fig. 4A). This was evident in terms of both iNKT cell percentage and relative number (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, JNK1 KO mice had an even greater iNKT cell loss post-infection than WT mice (Fig. 4C); this indicates that JNK2 (but not JNK1) contributes to the loss of iNKT cells following a VV infection.

Figure 4.

JNK2 (but not JNK1) contributes to the VV-induced loss of iNKT cells. (A) JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates were infected i.p. with VV. On day 4 p.i., LMNC were harvested and the cells were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and a TCRβ-specific mAb. (B) On day 4 p.i., the percentage of liver iNKT cells in VV-infected mice was compared to mock-infected mice. The change in the percentage of liver iNKT cells was normalized (mock=1) and plotted. Pooled data from four independent experiments are shown, with each dot representing an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM (n=9–12); *, p<0.05. (C) WT and JNK1 KO mice were infected i.p. with VV. On day 4 p.i., liver MNC were harvested and the cells were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and a TCRβ-specific mAb. The percentage of liver iNKT cells is shown, consisting of pooled data from two independent experiments, with each dot representing an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM (n=6); *, p<0.05.

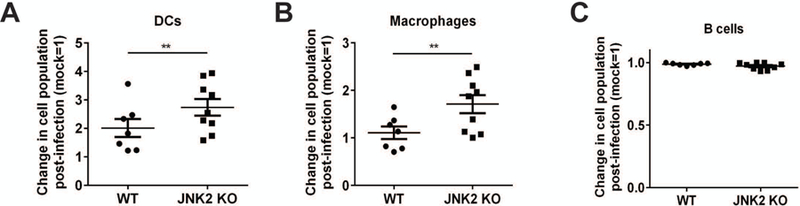

Increased DC and macrophage populations in JNK2 (but not JNK1) KO spleens.

We have found that a VV infection results in an increase in splenic MHC II+ F4/80+ cells (i.e., macrophages) in WT mice (Webb and Brutkiewicz, unpublished data). In the current study, we found a significant increase of splenic DCs (MHC II+CD11c+) as well as macrophages (MHC II+F4/80+) in WT mice following a VV infection (Fig. 5A and 5B). B cells (MHC II+ B220+) remained unchanged post-infection in both WT and JNK2 KO mice (Fig. 5C). There were significantly more DCs and macrophages that accumulated in the spleens of JNK2 KO compared to WT mice post-infection (Fig. 5A and 5B); changes in JNK1 KO DCs and macrophages following a VV infection were equivalent to WT (data not shown). Therefore, these data suggest that JNK2 suppresses the increase of DCs and macrophages following a VV infection. Further, this implies an important role for JNK2 in regulating overall immune responses following a VV infection. Because DCs and macrophages are important APCs for iNKT cells, the increased accumulation of these cells may explain, at least in part, why fewer JNK2 KO iNKT cells were lost post-infection as compared to WT.

Figure 5.

Increased DC and macrophage populations in JNK2 KO mice post-VV infection. JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates were infected with 1×106 pfu VV, i.p. On day 4 p.i., spleens were harvested and the splenocytes were stained with an MHC II- and a CD11c-specific mAb (A; DCs), an F4/80-specific mAb (B; macrophages) or a B220-specific mAb (C; B cells). The percentage of each cell type in VV-infected mice was compared to mock-infected and the change was normalized (mock=1) and plotted. Pooled data from four independent experiments are shown, with each dot representing an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM (n= 9–12); **, p<0.01.

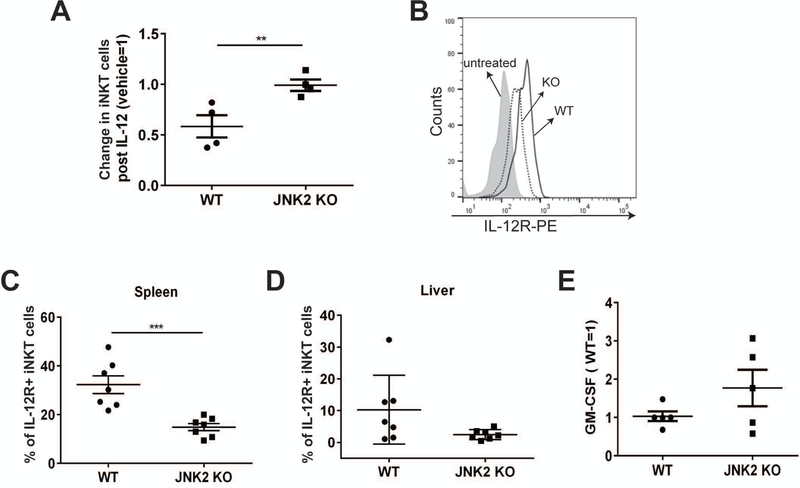

IL-12-mediated iNKT cell loss is dependent on JNK2

We and others have shown that the activation of iNKT cells following a viral infection is dependent on IL-12, but independent of CD1d [10, 12]. IL-12 can both activate iNKT cells and cause their loss by apoptosis [7, 9]. Because impaired IL-12 receptor (IL-12R) expression and reduced IL-12 signaling have been reported in JNK2-deficient CD4+ T cells [35], we hypothesized that JNK2 regulates the loss of iNKT cells following IL-12 treatment. To test this hypothesis, JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates were treated with IL-12 in vivo and the status of liver iNKT cells was determined. Liver iNKT cells in WT mice were reduced by ~60% following IL-12 treatment, whereas IL-12 had no effect on JNK2 KO iNKT cell levels (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, we found IL-12 treatment in vivo increased the expression of IL-12R on iNKT cells, but not on conventional T cells (Fig. S5). Compared to WT mice, fewer iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice expressed the IL-12R after IL-12 treatment in vivo (Fig. 6B–D). The TCR-dependent activation of JNK2 KO iNKT cells was not impaired, as they secreted a comparable amount of GM-CSF as those from WT mice when co-cultured with WT APCs (Fig. 6E). This suggests that the reduced iNKT cell loss or decreased IL-12R expression on iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice was unlikely due to impaired TCR signaling. Altogether, our results indicate that the reduction in iNKT cells following a VV infection or injection of IL-12, is dependent on JNK2.

Figure 6.

IL-12-mediated iNKT cell loss is JNK2-dependent. (A) JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates were injected i.v. with 0.5 μg/mouse of recombinant murine IL-12. LMNCs were harvested on day 2, and the cells were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers, and a TCRβ-specific mAb. The change in liver iNKT cells was normalized (vehicle=1) and plotted. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown, with each dot representing an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM (n= 4). (B, C and D) JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates were injected i.v. with recombinant murine IL-12. LMNCs and splenocytes were harvested on day 1. The cells were stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and mAbs against TCRβ and IL-12Rβ1. Splenic iNKT cells (tetramer+/TCR-β+) were gated and the levels of IL-12Rβ1 are shown in (B). The percentage of IL-12R+ splenic or liver iNKT cells is plotted in (C) and (D). (E) LMNCs were harvested from JNK2 KO mice and their WT littermates. These cells were co-cultured with α-GalCer-pulsed WT BMDCs for two days for the analysis of iNKT cell function. The production of GM-CSF into the supernatants was measured by ELISA and normalized (WT=1). Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown, with each dot representing an individual mouse. The data are plotted as the mean ± SEM (n= 6); **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Discussion

In the current study, we have shown that JNK2 (but not JNK1) impairs CD1d-mediated Ag presentation. Moreover, JNK2 is required for the reduction of iNKT cells following a VV infection or treatment with IL-12. Thus, overall, our results suggest that JNK2 has critical roles in both CD1d-dependent and CD1d-independent activation of iNKT cells.

We found that JNK2-deficient APCs have an enhanced ability to stimulate iNKT cells in vitro (Fig. 2). Although the activation markers on iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice were similar to those from WT mice, thymic JNK2 KO iNKT cells were actually larger than WT (Fig. 3C–E). It is well-known that lymphocytes become significantly larger in size upon stimulation; this increase in cell size correlates with activation status [45]. The larger cell size of thymic iNKT cells in JNK2 KO mice suggest these cells are likely more activated. This is consistent with our observation of an enhanced level of endogenous CD1d-mediated Ag presentation in JNK2-deficient cells. A previous study showed that JNK2-deficient Ag presenting cells (APCs) are comparable to WT APCs in presenting exogenous antigens (e.g, α-galactosylceramide; α-GalCer) to iNKT cells [46]. In fact, we have observed that as well (data not shown). However, it is important to note that in the current study, we demonstrated that iNKT cells co-cultured with JNK2-deficent APCs without adding exogenous lipid antigens produce more cytokines than those stimulated by WT APCs. Therefore, this strongly suggests that JNK2 signaling negatively regulates CD1d-mediated endogenous antigen presentation.

The reduced level of iNKT cells in the thymus and spleen is likely due to enhanced CD1d-mediated antigen presentation in JNK2-deficient APCs. It was reported that artificial antigen presenting cells with paracrine IL-2, activated CD8+ T cells, but also caused CD4+ T cell apoptosis [47]. Considering iNKT cells are mostly CD4+ T cells, enhanced Ag presentation by CD1d in JNK2-deficient APCs may result in iNKT cell apoptosis. Consistent with this idea, JNK2 KO mice have fewer thymic and splenic iNKT cells than WT mice. Activation-induced cell death (AICD) has long been described as a way for negative selection in thymus, but the mediators are not known or are controversial [48]. Fas-FasL interaction is important for mature T cell death in the periphery, whereas TRAIL, Bim and BCL-2 may be important for AICD and negative selection for T cells in the thymus. Further investigations are needed to study whether thymic iNKT cells from JNK2 KO mice express high levels of any of the cell death mediators.

An acute viral infection can result in iNKT cell apoptosis and the long-term loss of iNKT cells [10]. We and others have also shown that iNKT cell activation during a virus infection is dependent on IL-12, but not CD1d [10, 12, 13, 49]. Similar to a viral infection, IL-12 treatment also causes the loss of liver iNKT cells [7, 9]. Although the CD1d ligand α-GalCer can induce a temporary iNKT cell “loss”, this is simply by down-regulating the surface T cell receptor (TCR) [50, 51]. In the current study, we found that the reduction of liver iNKT cells in JNK2 KO mice following a VV infection or IL-12 treatment was less than that observed in WT mice. We believe this was likely due to impaired (or weak) IL-12 signaling in JNK2-deficient iNKT cells, because JNK2 KO iNKT cells have a baseline lower level of surface IL-12R expression. Pedra et al., reported that both conventional T and iNKT cells in JNK2 KO mice produce more IFN-γ following an infection with the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum, suggesting JNK2 is inhibitory for the production of IFN-γ [46]. This study appears to contradict a prior report showing JNK2 is required for IFN-γ expression [35]. The inconsistencies in the results between these studies, is likely due to differences in infection models and mouse strains.

Importantly, we did not observe any difference in TCR internalization or apoptosis between JNK2-deficient and WT iNKT cells. Subleski et al., proposed that iNKT cell loss in the liver following activation by α-GalCer or cytokines is probably due to a liver-specific mechanism of depleting iNKT cells, rather than TCR internalization or apoptosis [9]. It would be interesting to determine if JNK2 plays a role in this liver-specific regulation of iNKT cell depletion. Notably, we also observed increased infiltration of DCs and macrophages in the spleens of JNK2 KO mice on day 4 p.i. Thus, an important future question is whether the increase in DCs and macrophages in JNK2 KO mice post-infection is related to the reduced loss of iNKT cells.

JNK plays important roles in conventional T cell development and differentiation. In fact, JNK expression in T cells is strictly regulated [52]. Baseline expression of JNK in resting immune cells is very low [52]. After stimulation, there is a delayed increase in JNK activity and the generation of JNK1 and JNK2 proteins in CD4+ T cells [52]. Although JNK1-deficient CD4+ T cells can normally differentiate into Th1 cells in vitro, they exhibit enhanced Th2 differentiation [34]. JNK2-deficient CD4+ T cells also appear to be Th2-biased, as their differentiation into Th1 cells is impaired [35]. In an animal tumor model, JNK1 has been reported to be required for the effector function of CD8 (but not CD4) T cells [53]. Antiviral CD8+ T cell responses are also different in the absence of JNK1 or JNK2. Compared to WT mice, fewer virus-specific CD8+ T cells were activated in JNK1 KO mice and more virus-specific CD8+ T cells were present in JNK2 KO mice post-infection [32, 33]. Further studies have revealed that JNK1 is required for TCR-induced IL-2R gene expression [33]. On the other hand, JNK2 is important for IL-12R expression [35]. Consistently, we found reduced IL-12R expression on iNKT cells from JNK2-deficient mice. JNK1 and JNK2 involvement in different cytokine signaling pathways may explain their distinct functions in T cell activation.

Many studies have demonstrated that JNK1 and JNK2 have distinctly different functions in many classical physiological processes and disease models [27–29, 31–33, 39]. However, the results reported here are in the context of the CD1d/NKT cell axis. JNK1 and JNK2 are believed (at least in some settings) to have overlapping functions, because a double knockout of JNK1 and JNK2 is embryonic lethal, whereas JNK1 or JNK2 single knockout mice are quite viable [54, 55]. The distinct importance of JNK1 and JNK2 in diverse settings may be due to the differential expression of JNK1 and JNK2 in various tissues. For example, JNK1 appears to be the main JNK isoform in fibroblasts [25], whereas JNK2 is the main isoform expressed in mouse neutrophils [30]. We also found that JNK2 is dominantly expressed in BMDCs (Fig. S6). This may explain (in part) why JNK2 (but not JNK1) is important for CD1d-mediated Ag presentation. Another question is whether JNK1 and JNK2 can complement each other. It has been reported that JNK1 expression is not upregulated in JNK2 KO T cells [55]. Similarly, we did not observe any upregulation of JNK1 in JNK2-deficient cells or of JNK2 in JNK1-deficient cells (data not shown). These results suggest that JNK1 and JNK2 are not complementary when the other is absent.

Another possible mechanism of the specificity of JNK may be scaffold proteins. For example, JNK1 has been shown to be involved in TCR signaling in JNK2 KO CD8+ T cells mediated by the Plenty of SH3 (POSH) and JNK-interacting protein 1 complex [56]; this is consistent with the requirement of JNK1 in activating this subpopulation of conventional T cells [33]. In contrast, POSH regulates the activation of both JNK1 and JNK2 in CD4+ T cells [57], suggesting that the distinct functions of JNK1 and JNK2 may be due (at least in part) to their differential interaction with POSH scaffold complexes in specific subsets of T cells.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that JNK2 negatively regulates CD1d-mediated Ag presentation and contributes to the activation-induced cell death of iNKT cells following a virus infection or IL-12 treatment. This may be true for other innate or effector T cells that are responsive to IL-12 activation as well. Thus, our study contributes an important new piece for understanding the complex effect of JNK activation on different immune response elements.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice heterozygous for JNK1 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred to obtain JNK1 knockout (JNK1 KO) mice. C57BL/6 JNK2 KO mice and wildtype (WT) mice were also obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The mice were bred in specific pathogen-free facilities at the Indiana University School of Medicine. All mice were age- and sex-matched littermates; both male and female mice were used between 8 and 12 weeks of age in experiments. All animal procedures were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

shRNA construct and cell lines

JNK1/2 and negative control (NC) vectors were generated using the pLKO.1 vector (kindly provided by Dr. D. Riese, Auburn University, Auburn, AL). Oligonucleotides, 5’-CCGGAAAGAATGTCCTACCTTCTTTCTCGAGAAAGAAGGTAGGACATTCTTTTTTTT-3’, and 5’-AATTAAAAAAAAGAATGTCCTACCTTCTTTCTCGAGAAAGAAGGTAGGACATTCTTT-3’ were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) to target 5’-AAAGAATGTCCTACCTTCTTT-3’, a common sequence in both Jnk1 and Jnk2 mRNA (377 nucleotides downstream from the start codon) [58]. The oligonucleotides were annealed, phosphorylated, and ligated into the pLKO.1 vector. The target sequences for the NC was (5’-TCAGTCACGTTAATGGTCGTT- 3’). Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against JNK1, JNK2, MKK4 and MKK7 (all validated constructs in the pLKO.1 vector) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO; Table 1). Mouse LMTK-CD1d1 and human HEK293-CD1d cells were transfected with these plasmids using polyethylenimine as previously described [59]. Transfected cells were selected in puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich; 2 µg/ml for HEK293-CD1d cells and 10–25 µg/ml for LMTK-CD1d1 cells). Drug-resistant cells were pooled and used as stable cell lines.

Table 1:

Target sequences of the shRNA plasmids used in the current study

| Gene | Clone ID | Sequence (5' →3') |

|---|---|---|

| JNK1 | NM_016700.2-528s1c1 | CCGGGCAAATCTTTGCCAAGTGATTCTCGAGAATCACTTGGCAAAGATTTGCTTTTTG |

| JNK2 | NM_016961.2-607s1c1 | CCGGGCTAACTTATGTCAGGTTATTCTCGAGAATAACCTGACATAAGTTAGCTTTTTG |

| MKK4 | NM_003010.x-502s1c1 | CCGGCTTCTTATGGATTTGGATGTACTCGAGTACATCCAAATCCATAAGAAGTTTTT |

| MKK7 | NM_005043.x-1287s1c1 | CCGGCACAGGAAGAGACCAAAGTATCTCGAGATACTTTGGTCTCTTCCTGTGTTTTT |

Antibodies and reagents

Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramers and unloaded CD1d tetramers were obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Atlanta, GA). APC-, Phycoerythrin (PE)– and FITC–conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against murine NK-, B- or T cell-specific markers, including NK1.1, MHC II, CD11c, B220, CD1d (1B1), CD4, CD8 and TCRβ, and Annexin V were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). The human CD1d-specific 42.1 mAb and anti-mouse IL-12Rβ1 (CD212)-specific antibody were also from BD Biosciences. The GATA3 mAb was from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Propidium Iodide (PI) and antibodies for T-bet and RORγt were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Antibodies specific for phosphorylated JNK1/2, total JNK1/2, JNK1 or JNK2, were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Recombinant murine IL-12 was from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). The CD1d ligand α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY).

Virus, virus quantitation, and infection of mice and cells

The WR strain of VV was kindly provided by Drs. J. Yewdell and J. Bennink (Laboratory of Viral Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). VV stocks were propagated and titrated in human 143B osteosarcoma cells as previously described [60, 61]. Inactivation of VV by UV was performed by exposure of a VV stock to a short wave UV light source (254 nm) as previously described [17]. For in vivo infection of mice, VV was injected i.p. (1 × 106 plaque-forming units/mouse). For in vitro experiments, cells were infected with VV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 for the indicated times.

Western blot analysis

HEK293-CD1d, LMTK-CD1d1, L-CD1d.DR4 cells [5], splenocytes and BMDCs were lysed in 2% CHAPS lysis buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2% CHAPS, 0.02% sodium azide, and protease inhibitors] (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Sodium fluoride and sodium orthovanadate (1 mM each) were included to inhibit phosphatases. Lysates were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). The blot was processed using the indicated antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and then developed using chemiluminescence before exposure on film. Images were quantified using ImageJ (1.37v; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Flow cytometry

Thymocytes and splenocytes were prepared by standard procedures. Liver mononuclear cells (LMNCs) were harvested using density gradient centrifugation, as previously described [62]. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were generated from mouse bone marrow cells in a 7-day culture in the presence of IL-4 (10 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (10 ng/ml). Single-cell suspensions of 1×106 cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with the indicated antibodies. The cells were washed extensively in HBSS containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). All cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. For staining of transcription factors, cells were fixed and permeabilized using a staining buffer set (eBioscience). All cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur or LSRII (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

IL-12 treatment in vivo

WT and JNK2 KO mice were injected i.v. with 0.5 μg/mouse of recombinant murine IL-12. Spleens, livers and sera were harvested one or two days after IL-12 injection. Serum IFN-γ was measured by ELISA.

NKT cell co-culture assay

BMDCs from WT and JNK2 KO mice or LMTK-CD1d1 shRNA-expressing cells (5×105 cells/well) were incubated with the representative mouse type I NKT cell hybridoma N38–2C12 and type II NKT cell hybridoma N37–1A12 [63] in triplicate wells (5×104 cells/well) in 96-well microtiter plates for 24 h. IL-2 secreted in the supernatants was measured by ELISA. Co-culture assays of HEK293-CD1d cells with human iNKT cells, using GM-CSF production as a measure of Ag presentation, were as previously described [59].

In vitro stimulation of iNKT cells

LMNCs (2.5×105 cells/well) from WT and JNK2 KO mice were co-cultured with α-GalCer-pulsed BMDCs (5×105cells/well) in triplicate wells of 96-well microtiter plates. After a 48 h co-culture, the supernatants were collected for IFN-γ, IL-4 and GM-CSF analysis by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Graphs were generated and statistics calculated using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The mean of triplicate samples of a representative assay is shown with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (SEM). A Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was used. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Flow Cytometry Resource Facility, Indiana University School of Medicine for their assistance. We also would like to thank the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for providing empty and PBS75-loaded CD1d tetramers. Drs. J. Yewdell, J. Bennink and D. Riese generously provided critical reagents.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI046455, RO1 CA161178 and P01 AI056097 (to R.R.B.), and U54 DK106846, supporting the Indiana University School of Medicine’s Cooperative Center of Excellence in Hematology.

Abbreviations:

- Ag

antigen

- α-GalCer

α-galactoceramide

- APCs

Ag presenting cells

- B MDCs

bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

- DCs

dendritic cells

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-Monocyte Colony Stimulating Factor

- IFN

interferon

- IL-12R

IL-12 receptor

- iNKT

invariant natural killer T cells

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- KO

knockout

- LMNCs

liver mononuclear cells

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MKK

MAPK kinase

- MNC

mononuclear cells

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NKT cells

natural killer T cells

- p.i.

post-infection

- TCR

T cell receptor

- VV

vaccinia virus

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brutkiewicz RR, Lin Y, Cho S, Hwang YK, Sriram V and Roberts TJ, CD1d-mediated antigen presentation to natural killer T (NKT) cells. Crit Rev Immunol 2003. 23: 403–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brutkiewicz RR, CD1d ligands: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Immunol 2006. 177: 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brigl M and Brenner MB, How invariant natural killer T cells respond to infection by recognizing microbial or endogenous lipid antigens. Semin Immunol 2010. 22: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salio M, Silk JD and Cerundolo V, Recent advances in processing and presentation of CD1 bound lipid antigens. Curr Opin Immunol 2010. 22: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriram V, Cho S, Li P, O’Donnell PW, Dunn C, Hayakawa K, Blum JS and Brutkiewicz RR, Inhibition of glycolipid shedding rescues recognition of a CD1+ T cell lymphoma by natural killer T (NKT) cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002. 99: 8197–8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renukaradhya GJ, Webb TJ, Khan MA, Lin YL, Du W, Gervay-Hague J and Brutkiewicz RR, Virus-induced inhibition of CD1d1-mediated antigen presentation: reciprocal regulation by p38 and ERK. J Immunol 2005. 175: 4301–4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberl G and MacDonald HR, Rapid death and regeneration of NKT cells in anti-CD3ε- or IL-12-treated mice: a major role for bone marrow in NKT homeostasis. Immunity 1998. 9: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paget C, Mallevaey T, Speak AO, Torres D, Fontaine J, Sheehan KC, Capron M, Ryffel B, Faveeuw C, Leite de Moraes M, Platt F and Trottein F, Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity 2007. 27: 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subleski JJ, Hall VL, Wolfe TB, Scarzello AJ, Weiss JM, Chan T, Hodge DL, Back TC, Ortaldo JR and Wiltrout RH, TCR-dependent and -independent activation underlie liver-specific regulation of NKT cells. J Immunol 2011. 186: 838–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Y, Roberts TJ, Wang CR, Cho S and Brutkiewicz RR, Long-term loss of canonical NKT cells following an acute virus infection. Eur J Immunol 2005. 35: 879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigl M, Tatituri RV, Watts GF, Bhowruth V, Leadbetter EA, Barton N, Cohen NR, Hsu FF, Besra GS and Brenner MB, Innate and cytokine-driven signals, rather than microbial antigens, dominate in natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. J Exp Med 2011. 208: 1163–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeissig S, Murata K, Sweet L, Publicover J, Hu Z, Kaser A, Bosse E, Iqbal J, Hussain MM, Balschun K, Rocken C, Arlt A, Gunther R, Hampe J, Schreiber S, Baron JL, Moody DB, Liang TJ and Blumberg RS, Hepatitis B virus-induced lipid alterations contribute to natural killer T cell-dependent protective immunity. Nat Med 2012. 18: 1060–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holzapfel KL, Tyznik AJ, Kronenberg M and Hogquist KA, Antigen-dependent versus -independent activation of invariant NKT cells during infection. J Immunol 2014. 192: 5490–5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Chen X, Rodenkirch L, Simonson W, Wernimont S, Ndonye RM, Veerapen N, Gibson D, Howell AR, Besra GS, Painter GF, Huttenlocher A and Gumperz JE, Natural killer T-cell autoreactivity leads to a specialized activation state. Blood 2008. 112: 4128–4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renukaradhya GJ, Khan MA, Shaji D and Brutkiewicz RR, Vesicular stomatitis virus matrix protein impairs CD1d-mediated antigen presentation through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. J Virol 2008. 82: 12535–12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez DJ, Gumperz JE and Ganem D, Regulation of CD1d expression and function by a herpesvirus infection. J Clin Invest 2005. 115: 1369–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb TJ, Litavecz RA, Khan MA, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Renukaradhya GJ and Brutkiewicz RR, Inhibition of CD1d1-mediated antigen presentation by the vaccinia virus B1R and H5R molecules. Eur J Immunol 2006. 36: 2595–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan W, Dasgupta A and Cresswell P, Herpes simplex virus evades natural killer T cell recognition by suppressing CD1d recycling. Nat Immunol 2006. 7: 835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N, McCarthy C, Drakesmith H, Li D, Cerundolo V, McMichael AJ, Screaton GR and Xu XN, HIV-1 down-regulates the expression of CD1d via Nef. Eur J Immunol 2006. 36: 278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho S, Knox KS, Kohli LM, He JJ, Exley MA, Wilson SB and Brutkiewicz RR, Impaired cell surface expression of human CD1d by the formation of an HIV-1 Nef/CD1d complex. Virology 2005. 337: 242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brutkiewicz RR, Cell Signaling Pathways That Regulate Antigen Presentation. J Immunol 2016. 197: 2971–2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon G, Callahan MA, Gronemus JQ and Lowy RJ, Early activation of MAP kinases by influenza A virus X-31 in murine macrophage cell lines. PLoS One 2014. 9: e105385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu N, Yu R, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, Ostrwoski MA and Yu Q, Role of cell signaling in poxvirus-mediated foreign gene expression in mammalian cells. Vaccine 2009. 27: 2994–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis RJ, Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000. 103: 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochedlinger K, Wagner EF and Sabapathy K, Differential effects of JNK1 and JNK2 on signal specific induction of apoptosis. Oncogene 2002. 21: 2441–2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joetham A, Schedel M, Takeda K, Jia Y, Ashino S, Dakhama A, Lluis A, Okamoto M and Gelfand EW, JNK2 regulates the functional plasticity of naturally occurring T regulatory cells and the enhancement of lung allergic responses. J Immunol 2014. 193: 2238–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denninger K, Rasmussen S, Larsen JM, Orskov C, Seier Poulsen S, Sorensen P, Christensen JP, Illges H, Odum N and Labuda T, JNK1, but not JNK2, is required in two mechanistically distinct models of inflammatory arthritis. Am J Pathol 2011. 179: 1884–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guma M, Kashiwakura J, Crain B, Kawakami Y, Beutler B, Firestein GS, Kawakami T, Karin M and Corr M, JNK1 controls mast cell degranulation and IL-1β production in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010. 107: 22122–22127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh R, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Tanaka KE, Gaarde WA and Czaja MJ, Differential effects of JNK1 and JNK2 inhibition on murine steatohepatitis and insulin resistance. Hepatology 2009. 49: 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukhumavasi W, Egan CE and Denkers EY, Mouse neutrophils require JNK2 MAPK for Toxoplasma gondii-induced IL-12p40 and CCL2/MCP-1 release. J Immunol 2007. 179: 3570–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varona-Santos JL, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Sanabria NY, Ijaz A, Atsushi M, Ichii H, Pastori RL, Inverardi L, Ricordi C and Fornoni A, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 is deleterious to the function and survival of murine pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 2008. 51: 2271–2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbour N, Naniche D, Homann D, Davis RJ, Flavell RA and Oldstone MB, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)1 and JNK2 signaling pathways have divergent roles in CD8+ T cell-mediated antiviral immunity. J Exp Med 2002. 195: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conze D, Krahl T, Kennedy N, Weiss L, Lumsden J, Hess P, Flavell RA, Le Gros G, Davis RJ and Rincon M, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)1 and JNK2 have distinct roles in CD8+ T cell activation. J Exp Med 2002. 195: 811–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong C, Yang DD, Wysk M, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ and Flavell RA, Defective T cell differentiation in the absence of Jnk1. Science 1998. 282: 2092–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang DD, Conze D, Whitmarsh AJ, Barrett T, Davis RJ, Rincon M and Flavell RA, Differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells requires MAP kinase JNK2. Immunity 1998. 9: 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong C, Yang DD, Tournier C, Whitmarsh AJ, Xu J, Davis RJ and Flavell RA, JNK is required for effector T-cell function but not for T-cell activation. Nature 2000. 405: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tournier C, Dong C, Turner TK, Jones SN, Flavell RA and Davis RJ, MKK7 is an essential component of the JNK signal transduction pathway activated by proinflammatory cytokines. Genes Dev 2001. 15: 1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haeusgen W, Herdegen T and Waetzig V, The bottleneck of JNK signaling: molecular and functional characteristics of MKK4 and MKK7. Eur J Cell Biol 2011. 90: 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sukhumavasi W, Warren AL, Del Rio L and Denkers EY, Absence of mitogen-activated protein kinase family member c-Jun N-terminal kinase-2 enhances resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Exp Parasitol 2010. 126: 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kronenberg M and Gapin L, The unconventional lifestyle of NKT Cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2002. 2: 557–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S, Dhodapkar KM and Krasovsky J, A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med 2003. 197: 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coles MC and Raulet DH, NK1.1+ T cells in the liver arise in the thymus and are selected by interactions with class I molecules on CD4+CD8+ cells. J Immunol 2000. 164: 2412–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buechel HM, Stradner MH and D’Cruz LM, Stages versus subsets: Invariant Natural Killer T cell lineage differentiation. Cytokine 2015. 72: 204–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobbs JA, Cho S, Roberts TJ, Sriram V, Zhang J, Xu M and Brutkiewicz RR, Selective loss of natural killer T cells by apoptosis following infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol 2001. 75: 10746–10754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teague TK, Munn L, Zygourakis K and McIntyre BW, Analysis of lymphocyte activation and proliferation by video microscopy and digital imaging. Cytometry 1993. 14: 772–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedra JH, Mattner J, Tao J, Kerfoot SM, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Askenase PW, Yin Z and Fikrig E, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 2 inhibits gamma interferon production during Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. Infect Immun 2008. 76: 308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Obesity and overweight World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green DR, Droin N and Pinkoski M, Activation-induced cell death in T cells. Immunol Rev 2003. 193: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyznik AJ, Verma S, Wang Q, Kronenberg M and Benedict CA, Distinct requirements for activation of NKT and NK cells during viral infection. J Immunol 2014. 192: 3676–3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parekh VV, Singh AK, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Bezbradica JS, Inazawa H, Ehara H, Sakai T, Serizawa I, Wu L, Wang CR, Joyce S and Van Kaer L, Quantitative and qualitative differences in the in vivo response of NKT cells to distinct α- and β-anomeric glycolipids. J Immunol 2004. 173: 3693–3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crowe NY, Uldrich AP, Kyparissoudis K, Hammond KJ, Hayakawa Y, Sidobre S, Keating R, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ and Godfrey DI, Glycolipid antigen drives rapid expansion and sustained cytokine production by NK T cells. J Immunol 2003. 171: 4020–4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss L, Whitmarsh AJ, Yang DD, Rincon M, Davis RJ and Flavell RA, Regulation of c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase (Jnk) gene expression during T cell activation. J Exp Med 2000. 191: 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao Y, Tao J, Li MO, Zhang D, Chi H, Henegariu O, Kaech SM, Davis RJ, Flavell RA and Yin Z, JNK1 is essential for CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor immune surveillance. J Immunol 2005. 175: 5783–5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuan CY, Yang DD, Samanta Roy DR, Davis RJ, Rakic P and Flavell RA, The Jnk1 and Jnk2 protein kinases are required for regional specific apoptosis during early brain development. Neuron 1999. 22: 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabapathy K, Jochum W, Hochedlinger K, Chang L, Karin M and Wagner EF, Defective neural tube morphogenesis and altered apoptosis in the absence of both JNK1 and JNK2. Mech Dev 1999. 89: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham CA, Knudson KM, Peng BJ, Teixeiro E and Daniels MA, The POSH/JIP-1 scaffold network regulates TCR-mediated JNK1 signals and effector function in CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol 2013. 43: 3361–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cunningham CA, Cardwell LN, Guan Y, Teixeiro E and Daniels MA, POSH Regulates CD4+ T Cell Differentiation and Survival. J Immunol 2016. 196: 4003–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li G, Xiang Y, Sabapathy K and Silverman RH, An apoptotic signaling pathway in the interferon antiviral response mediated by RNase L and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 2004. 279: 1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu J, Shaji D, Cho S, Du W, Gervay-Hague J and Brutkiewicz RR, A threonine-based targeting signal in the human CD1d cytoplasmic tail controls its functional expression. J Immunol 2010. 184: 4973–4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roberts TJ, Sriram V, Spence PM, Gui M, Hayakawa K, Bacik I, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW and Brutkiewicz RR, Recycling CD1d1 molecules present endogenous antigens processed in an endocytic compartment to NKT cells. J Immunol 2002. 168: 5409–5414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bacik I, Cox JH, Anderson R, Yewdell JW and Bennink JR, TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing)-independent presentation of endogenously synthesized peptides is enhanced by endoplasmic reticulum insertion sequences located at the amino- but not carboxyl-terminus of the peptide. J Immunol 1994. 152: 381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tupin E and Kronenberg M, Activation of natural killer T cells by glycolipids. Methods Enzymol 2006. 417: 185–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gui M, Li J, Wen LJ, Hardy RR and Hayakawa K, TCR β chain influences but does not solely control autoreactivity of Vα14Jα281 T cells. J Immunol 2001. 167: 6239–6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.