ABSTRACT

In biology, function arises from form. For bacterial secretion systems, which often span two membranes, avidly bind to the cell wall, and contain hundreds of individual proteins, studying form is a daunting task, made possible by electron cryotomography (ECT). ECT is the highest-resolution imaging technique currently available to visualize unique objects inside cells, providing a three-dimensional view of the shapes and locations of large macromolecular complexes in their native environment. Over the past 15 years, ECT has contributed to the study of bacterial secretion systems in two main ways: by revealing intact forms for the first time and by mapping components into these forms. Here we highlight some of these contributions, revealing structural convergence in type II secretion systems, structural divergence in type III secretion systems, unexpected structures in type IV secretion systems, and unexpected mechanisms in types V and VI secretion systems. Together, they offer a glimpse into a world of fantastic forms—nanoscale rotors, needles, pumps, and dart guns—much of which remains to be explored.

INTRODUCTION

The envelope of bacterial cells consists of at least one—and often two—membranes, a cell wall, and possibly a surface layer. This envelope allows cells to differentiate themselves from their environment and handle the resulting osmotic pressure, but it also presents a significant obstacle. Anything a cell wishes to export, from a motility appendage to a plasmid, needs to be ushered across this barrier. To accomplish this, bacteria have evolved a battery of secretion systems. Secretion systems are often constructed from dozens of protein building blocks embedded in the cell’s envelope. The size, complexity, and location of these machines make them a particular challenge for structural characterization. High-resolution structure determination techniques such as X-ray crystallography and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)-based single-particle reconstruction (SPR) require objects to be purified from their cellular environment. This is problematic for membrane-associated proteins, which embed in the lipid bilayer by means of exposed hydrophobic patches. These patches can be protected during purification by adding detergents to the solvent, but often structural alterations still occur. Secretion systems are also unusually large targets and frequently lose peripheral or loosely-associated components during purification. In addition, they often cross two membranes and are avidly linked to the cell wall.

Before the advent of electron cryotomography (ECT), we knew an impressive amount about what secretion systems are made of; genetics revealed components, biochemistry revealed their properties, and X-ray crystallography and SPR revealed the structures of purified pieces. But we knew much less about how the pieces fit together into a functional whole. For that, we turned to a complementary technique: ECT. While other techniques reveal structural details of purified components, ECT can be applied directly to intact cells. Briefly, a small volume of bacterial culture is applied to an EM support grid. This grid is then plunged into a cryogen that freezes the sample so quickly that the water cannot crystallize, instead remaining amorphous. The cells are thereby immobilized in a fully hydrated, native state. This frozen sample is then transferred to the TEM for cryo-EM imaging. A three-dimensional reconstruction of a cell is built up from two-dimensional projection images taken from different angles, accomplished by rotating the sample between images. This reconstruction, or tomogram, shows a snapshot of the contents of the cell without fixatives or stains, typically with a mid-range resolution (∼5 nm) sufficient to see the shapes of large macromolecular complexes like secretion systems and their abundance and distribution in the cell. This can be particularly powerful for machines that exist in multiple states in vivo, only one of which may persist through purification. Images of different copies of the same structure, in the same cell or from many cells, can be merged by subtomogram averaging to generate a higher signal-to-noise view of the structure’s inflexible regions (flexible or variable regions get washed out in the average, along with density from nearby but unassociated proteins) (1). While the resolution of these averages is still too low to unambiguously orient atomic structures, in ideal cases, we can combine the information ECT provides about the form(s) of a structure in situ with high-resolution knowledge about its isolated components from complementary structural biology techniques.

ECT has served the study of bacterial secretion systems in two main ways: first, by simply showing what structures look like inside cells, and second, by revealing the relative arrangement of building blocks within those structures. This has provided some spectacular glimpses into how form is transformed into function, which in some cases have dramatically advanced fields of research. Here we briefly highlight some examples of these insights into bacterial secretion systems provided by ECT; the biology of the systems is detailed elsewhere. For recent, in-depth reviews of the subject, including both ECT and SPR, we recommend references 2 and 3. In addition, reference 4 provides an excellent overview of the diversity of bacterial secretion systems.

TYPE II SECRETION SYSTEMS

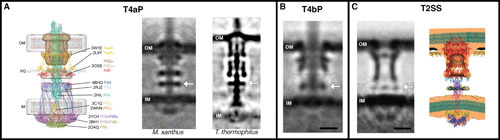

Capturing snapshots of cellular machinery in different states can often yield insights into how it works. For instance, ECT of the type IVa pilus (T4aP)—a type II secretion system (T2SS)-related machine that extends and retracts a long extracellular pilus for motility—showed that the structure comprises a series of stacked rings spanning the periplasm (Fig. 1A) (5). Imaging structures with and without pili assembled revealed how these rings undergo an ∼3-nm rearrangement to ungate the channel and allow the assembling filament to extend out of the cell (5, 6).

FIGURE 1.

T2SS. (A) ECT revealed the structures of the T4aP in Myxococcus xanthus and Thermus thermophilus, enabling high-resolution structures to be placed into the map to produce a hypothetical model of the machine. Further studies revealed structural convergence of the related T4bP in Vibrio cholerae (B) and T2SS in Legionella pneumophila (C), with a similar periplasmic ring (arrows) formed by nonhomologous proteins in each system. Note in this and subsequent figures how bacterial secretion systems often locally distort the cell envelope in vivo. Images are reprinted from the following with permission: panel A left and middle, reference 6; panel A right, reference 5; panel B, reference 29; and panel C, reference 31.

For the T4aP, the high-resolution structures of many components had been solved, and biochemical interactions between many components had been worked out (7–28). Still, how the pieces fit together was a puzzle. To solve it, we applied ECT to a series of mutant strains in which T4aP components were deleted or tagged with additional protein density. By looking for corresponding absences or additions in the structure, we deduced the approximate locations of the components. Guided by clues from biochemical studies, we could thus place each high-resolution three-dimensional puzzle piece in its proper location (Fig. 1A) (6). Knowing where different pieces lie in the finished form often gives clues about how they might function. For instance, we saw that the ATPase in the cytoplasm was leveraged by a clamp connected to the integrated system of rings. This likely allows the assembly ATPase to rotate an adapter protein in the inner membrane (IM) to scoop pilin subunits from the membrane into the assembling pilus. Switching to a retraction mode, the clamp recruits a different ATPase to release subunits back into the IM. The signal for this switch from extension to retraction is likely sensed by a ring in the periplasm and transmitted through coiled-coil domains to the ATPase clamp (6).

Often, knowing the map of one structure has a domino effect, triggering insights into other, related machines. ECT of the type IVb pilus (T4bP) revealed a structure strikingly similar to that of the T4aP despite the fact that only half its components have homologs in the T4aP (Fig. 1B) (29). For instance, a ring in the periplasm thought to act as a sensor in the T4aP is also present in the T4bP, but it is formed by an unrelated protein. Another member of the family, the pathogenic T2SS, does not assemble a long extracellular pilus filament but rather pumps out effector proteins (30). Again, ECT mapping found the same ring, again formed by a nonconserved protein (Fig. 1C). In this case, the ring was flexible with respect to the rest of the machine, suggesting a possible role in loading cargo (31).

TYPE III SECRETION SYSTEMS

The first secretion system studied by ECT was the type III secretion system (T3SS)-based flagellar motor, responsible for assembling, and subsequently rotating, the long flagellar filaments that propel the motility of many bacterial cells (32). The flagellar motor had been a subject of fascination for decades, and elements of its mechanism (33) and components (34) were well understood. Numerous EM studies, including SPR, of purified motors had revealed its core structure (for examples, see references 35 to 40). Still, key details remained unresolved, including the structure of the export complex in the cytoplasm responsible for assembling the machine and the interaction between the rotating (rotor) and stationary (stator) portions of the motor. ECT studies were able to reveal the interactions between these components, as well as the structure and location of peripheral components lost upon purification, such as the export apparatus (32, 41–43).

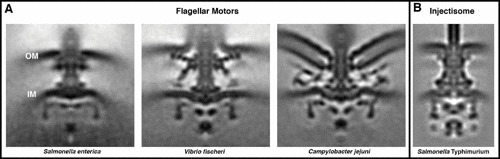

One of the most striking observations that came from studying flagellar motors in situ was how their form is adapted to the lifestyles of different species (Fig. 2A) (44). For instance, homologous components come together in different stoichiometries to form rings of different diameters, allowing the motor to gear up or down and generate different amounts of torque (32, 45–47). Some species (particularly pathogens) have elaborated their motors with additional components, perhaps to stabilize them against the increased load of more viscous environments (48) or to keep their associated filaments sheathed in membrane (49).

FIGURE 2.

T3SS. ECT and subtomogram averaging revealed the in situ structures of diverse T3SSs, including the flagellar motors of many bacteria (three examples, from Salmonella enterica, Vibrio fischeri, and Campylobacter jejuni) (A) and the injectisome from Salmonella Typhimurium (B). Structures shown from left to right: EMD-3154, EMD-3155, and EBD-3150 from reference 45 and EMD-2667 from reference 52.

Pathogenic bacteria like Yersinia and Salmonella use a different T3SS to assemble, instead of a motility apparatus, a needle-like injectisome to deliver effector proteins not only across the bacterium’s envelope but also further past the membrane of a target host cell (50). Injectisomes and flagellar motors are constructed from homologous components but serve strikingly different functions (Fig. 2B) (51). In an example of how seeing the shapes of machines in situ can provide clues about how they work, ECT revealed how the export apparatus—also known as the sorting complex—differs from that of the flagellar motor, with subunits forming no longer a wide rotary ring but rather radial spokes better suited to recognize and feed diverse effector proteins to the central export channel (52). Comparing ECT images of injectisomes in vivo with and without the sorting complex showed how the radial symmetry induces a dramatic rearrangement of a ring at the base of the needle (53). Even inside the cell, the sorting complex is fragile; deletion of individual components often disrupts the whole complex (53, 54). These pieces can, however, be functionally tagged with additional protein density, which allowed them to be mapped by ECT. Knowing where components are located, and in what orientation, often provides important clues about how the system works. For instance, seeing that the substrate/chaperone-binding domain of the ATPase sits adjacent to the export gate suggests that the cage of the sorting complex forms an antechamber in which substrates are prepared for secretion (53).

Recently, ECT was used to capture the interaction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium injectisomes with host cells, revealing the translocon pore at the tip of the complex in the host membrane and supporting a model of direct injection of substrates across the host membrane (55). The translocon was much smaller (∼13.5-nm outer diameter) than a homologous structure from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) previously reconstituted in liposomes (∼55 to 65 nm) (56), underscoring the importance of studying secretion systems in situ.

TYPE IV SECRETION SYSTEMS

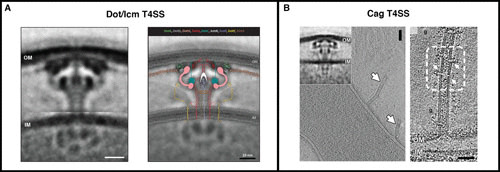

Attempting to purify structures out of the cell often leads to confounding alterations. For instance, SPR structures of purified type IV secretion systems (T4SSs) showed a chamber adjacent to the outer membrane (OM), connected to the IM by a solid stalk, suggesting that substrates enter the outer chamber from the periplasm (57, 58). It was therefore a surprise when ECT structures of the Dot/Icm T4SS in situ revealed instead an open channel extending through the periplasm (Fig. 3A) (59, 60). This feature, together with observations of complex assemblies of multiple ATPases in the cytoplasm and flexible “wings” in the periplasm (59–61), suggests that there might be two paths by which substrates could pass through the Dot/Icm T4SS: one through the central channel from the cytoplasm and one laterally into the outer chamber from the periplasm (60). This could help explain how the system can export such a spectacular number (∼300) of discrete effectors (62).

FIGURE 3.

T4SS. (A) ECT revealed the in situ structure of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm T4SS, including a central channel extending from the inner membrane, and enabled components to be placed in the map. (B) It also revealed the similar structure of the Helicobacter pylori cag T4SS (inset), as well as novel, related OM tubes. Images are reprinted from the following with permission: panel A, reference 60 (but see also reference 59); panel B, reference 61.

Putting structures in context inside the cell can answer many questions, but it often raises more. ECT images of the cag T4SS in Helicobacter pylori showed periplasmic machines structurally very similar to the Dot/Icm T4SS. Next to them, however, we sometimes saw wide (∼40-nm) OM tubes, studded with portals, extending outward up to 500 nm from the cell (Fig. 3B) (61). The two structures appear to be related, but how, and what the resulting mechanism of effector secretion might be, remains puzzling.

TYPE V SECRETION SYSTEMS

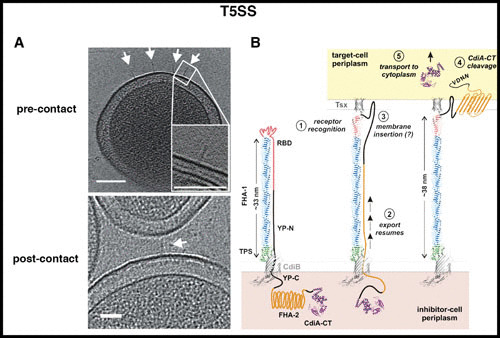

Sometimes, even seeing something as simple as a stick can be illuminating. Many bacteria kill nearby cells through the process of contact-dependent inhibition (CDI). In E. coli this process is mediated by a type V secretion system (T5SS) comprising two proteins: (i) CdiB, a β-barrel in the OM that secretes (ii) CdiA, a large multidomain protein containing the toxin (63). It was known that toxin translocation is mediated by interaction of CdiA with a receptor, BamA, on the target cell (64), but the mechanism was unknown. Using ECT, we saw that CdiA forms rods extending out from the surface of the cell (Fig. 4A), but the length of the rod was only half that predicted for the protein. This explained why the receptor recognition domain is located in the middle of the protein (65) and helped elucidate a novel mechanism whereby CdiB initially secretes only the N-terminal half of CdiA, which forms a structured rod. The rest of the protein, including the C-terminal toxin, remains sequestered in the periplasm; target binding at the end of the rod stimulates secretion to continue, bringing the toxin-laden tip out of the periplasm and, like a tetherball, into the target cell (Fig. 4B) (66).

FIGURE 4.

T5SS. ECT revealed the stick-like form of the Escherichia coli CDI T5SS (A) (arrows) and helped elucidate its mechanism, in which half of CdiA extends out from the cell surface (B). Upon target binding, the remaining half of CdiA is exported to deliver the toxin to the target cell. Images reprinted with permission from reference 66.

TYPE VI SECRETION SYSTEMS

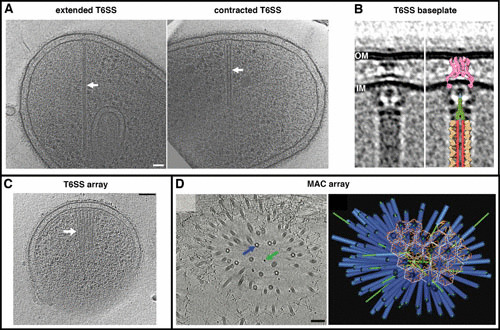

In 2005, our group observed tubular structures in cryotomograms of Vibrio cholerae (Fig. 5A) but did not know what they were until, with John Mekalanos, we recognized them as type VI secretion systems (T6SS), which allow some bacteria to kill others from different species (67). Our cryotomograms immediately revealed the basic mechanism: two nested tubes, a sheath and a rod, function as a nanoscale dart gun (68; also recognized in reference 69). Firing entails a constriction in the outer sheath, providing the energy to propel the inner rod, loaded with toxin, through the machine’s baseplate in the cell’s own envelope and then through the membrane of a neighboring target (68). Subsequent ECT studies revealed additional details, including the structure of the baseplate (Fig. 5B) (70, 71) and higher-resolution details of the sheath that showed how its contraction may expose recycling domains, allowing it to be disassembled into the building blocks of another T6SS (70). We showed that T6SS assemble extensive batteries in some species (Fig. 5C) and that other cells lyse to release micrometer-scale porcupine arrays of T6SS-related structures (Fig. 5D) (72). Some details remain mysterious: could the extracellular fibers associated with T6SS in vivo (70) mediate target recognition?

FIGURE 5.

T6SS. ECT revealed the contractile mechanism of the T6SS (A) and its structure in situ in Myxococcus xanthus (B). It also revealed higher-order arrays of T6SS in Amoebophilus asiaticus (C) and a T6SS-related metamorphosis-associated contractile structure (MAC) in Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (D). Images are reprinted from the following with permission: panels A and B, reference 70; panel D, reference 72.

OUTLOOK

Much work lies ahead. As described above, the machines we have managed to glimpse inside cells, or even map in detail, still hold many mysteries. In addition, systems studied in one species need to be compared across others; as the T3SS flagellar motor showed, they can be strikingly diverse. Some machines, including the type I, VII, VIII, and IX secretion systems, have yet to be seen at all in vivo. Others, including the T2SS and T4SS, have been observed only in an inactive state, and it is now of great interest to see their active forms. In some cases, this will require capturing pathogens interacting with their hosts, samples too thick for direct imaging by ECT. The developing application of focused ion beam (FIB) milling to thin such biological samples should soon open up even these targets for observation (73).

The study of bacterial secretion systems has always been intricately linked to the development of ECT technology. ECT requires highly specialized, expensive equipment and considerable expertise. As a result, the studies we have described here come from only a handful of labs. Fortunately, secretion systems have proven to be wonderful test beds for pioneering new ECT technology. Our subtomogram average of the flagellar motor was one of the first subtomogram averages (32). Our subsequent comparison of flagellar motors in different species was the result of establishing a pipeline to collect many (∼40) datasets per day (44). Our dissection of the T4aP by imaging strains with green fluorescent protein tags was the first to demonstrate that approach (6). The Pilhofer lab’s cryo-FIB milling of bacterial cells to study the T6SS was one of the first examples of that application (74). No doubt more discoveries about these fascinating nanomachines will come from continuing development of ECT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to our colleagues whose work we could not discuss due to limited space, and we thank members of the Jensen lab for helpful discussions.

Work on bacterial secretion systems in the lab is supported by the NIH (grant R01 AI127401 to G.J.J.).

Contributor Information

Catherine M. Oikonomou, Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125

Grant J. Jensen, Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Pasadena, CA 91125.

Maria Sandkvist, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Eric Cascales, CNRS Aix-Marseille Université, Mediterranean Institute of Microbiology, Marseille, France.

Peter J. Christie, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, McGovern Medical School, Houston, Texas

REFERENCES

- 1.Oikonomou CM, Jensen GJ. 2017. Cellular electron cryotomography: toward structural biology in situ. Annu Rev Biochem 86:873–896. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapisarda C, Tassinari M, Gubellini F, Fronzes R. 2018. Using cryo-EM to investigate bacterial secretion systems. Annu Rev Microbiol 72:231–254. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kooger R, Szwedziak P, Böck D, Pilhofer M. 2018. CryoEM of bacterial secretion systems. Curr Opin Struct Biol 52:64–70. 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa TR, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Meir A, Prevost MS, Redzej A, Trokter M, Waksman G. 2015. Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:343–359. 10.1038/nrmicro3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold VA, Salzer R, Averhoff B, Kühlbrandt W. 2015. Structure of a type IV pilus machinery in the open and closed state. eLife 4:e07380. 10.7554/eLife.07380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang YW, Rettberg LA, Treuner-Lange A, Iwasa J, Søgaard-Andersen L, Jensen GJ. 2016. Architecture of the type IVa pilus machine. Science 351:aad2001. 10.1126/science.aad2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abendroth J, Murphy P, Sandkvist M, Bagdasarian M, Hol WG. 2005. The X-ray structure of the type II secretion system complex formed by the N-terminal domain of EpsE and the cytoplasmic domain of EpsL of Vibrio cholerae. J Mol Biol 348:845–855. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig L, Volkmann N, Arvai AS, Pique ME, Yeager M, Egelman EH, Tainer JA. 2006. Type IV pilus structure by cryo-electron microscopy and crystallography: implications for pilus assembly and functions. Mol Cell 23:651–662. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balasingham SV, Collins RF, Assalkhou R, Homberset H, Frye SA, Derrick JP, Tønjum T. 2007. Interactions between the lipoprotein PilP and the secretin PilQ in Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol 189:5716–5727. 10.1128/JB.00060-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamagata A, Tainer JA. 2007. Hexameric structures of the archaeal secretion ATPase GspE and implications for a universal secretion mechanism. EMBO J 26:878–890. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601544. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satyshur KA, Worzalla GA, Meyer LS, Heiniger EK, Aukema KG, Misic AM, Forest KT. 2007. Crystal structures of the pilus retraction motor PilT suggest large domain movements and subunit cooperation drive motility. Structure 15:363–376. 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.018. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayers M, Sampaleanu LM, Tammam S, Koo J, Harvey H, Howell PL, Burrows LL. 2009. PilM/N/O/P proteins form an inner membrane complex that affects the stability of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus secretin. J Mol Biol 394:128–142. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.034. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abendroth J, Mitchell DD, Korotkov KV, Johnson TL, Kreger A, Sandkvist M, Hol WG. 2009. The three-dimensional structure of the cytoplasmic domains of EpsF from the type 2 secretion system of Vibrio cholerae. J Struct Biol 166:303–315. 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.03.009. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulyha I, Schmidt C, Lenz P, Jakovljevic V, Höne A, Maier B, Hoppert M, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2009. Regulation of the type IV pili molecular machine by dynamic localization of two motor proteins. Mol Microbiol 74:691–706. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06891.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampaleanu LM, Bonanno JB, Ayers M, Koo J, Tammam S, Burley SK, Almo SC, Burrows LL, Howell PL. 2009. Periplasmic domains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PilN and PilO form a stable heterodimeric complex. J Mol Biol 394:143–159. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.037. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misic AM, Satyshur KA, Forest KT. 2010. P. aeruginosa PilT structures with and without nucleotide reveal a dynamic type IV pilus retraction motor. J Mol Biol 400:1011–1021. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.066. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karuppiah V, Hassan D, Saleem M, Derrick JP. 2010. Structure and oligomerization of the PilC type IV pilus biogenesis protein from Thermus thermophilus. Proteins 78:2049–2057. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karuppiah V, Derrick JP. 2011. Structure of the PilM-PilN inner membrane type IV pilus biogenesis complex from Thermus thermophilus. J Biol Chem 286:24434–24442. 10.1074/jbc.M111.243535. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korotkov KV, Johnson TL, Jobling MG, Pruneda J, Pardon E, Héroux A, Turley S, Steyaert J, Holmes RK, Sandkvist M, Hol WG. 2011. Structural and functional studies on the interaction of GspC and GspD in the type II secretion system. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002228. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002228. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tammam S, Sampaleanu LM, Koo J, Sundaram P, Ayers M, Chong PA, Forman-Kay JD, Burrows LL, Howell PL. 2011. Characterization of the PilN, PilO and PilP type IVa pilus subcomplex. Mol Microbiol 82:1496–1514. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07903.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu S, Kelly G, Wang X, Frenkiel T, Shevchik VE, Pickersgill RW. 2012. Solution structure of homology region (HR) domain of type II secretion system. J Biol Chem 287:9072–9080. 10.1074/jbc.M111.300624. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georgiadou M, Castagnini M, Karimova G, Ladant D, Pelicic V. 2012. Large-scale study of the interactions between proteins involved in type IV pilus biology in Neisseria meningitidis: characterization of a subcomplex involved in pilus assembly. Mol Microbiol 84:857–873. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08062.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karuppiah V, Collins RF, Thistlethwaite A, Gao Y, Derrick JP. 2013. Structure and assembly of an inner membrane platform for initiation of type IV pilus biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E4638–E4647. 10.1073/pnas.1312313110. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Wallace RA, Black WP, Li YZ, Yang Z. 2013. Type IV pilus proteins form an integrated structure extending from the cytoplasm to the outer membrane. PLoS One 8:e70144. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070144. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu C, Turley S, Marionni ST, Park YJ, Lee KK, Patrick M, Shah R, Sandkvist M, Bush MF, Hol WG. 2013. Hexamers of the type II secretion ATPase GspE from Vibrio cholerae with increased ATPase activity. Structure 21:1707–1717. 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.027. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tammam S, Sampaleanu LM, Koo J, Manoharan K, Daubaras M, Burrows LL, Howell PL. 2013. PilMNOPQ from the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus system form a transenvelope protein interaction network that interacts with PilA. J Bacteriol 195:2126–2135. 10.1128/JB.00032-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich C, Bulyha I, Søgaard-Andersen L. 2014. Outside-in assembly pathway of the type IV pilus system in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 196:378–390. 10.1128/JB.01094-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siewering K, Jain S, Friedrich C, Webber-Birungi MT, Semchonok DA, Binzen I, Wagner A, Huntley S, Kahnt J, Klingl A, Boekema EJ, Søgaard-Andersen L, van der Does C. 2014. Peptidoglycan-binding protein TsaP functions in surface assembly of type IV pili. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E953–E961. 10.1073/pnas.1322889111. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YW, Kjær A, Ortega DR, Kovacikova G, Sutherland JA, Rettberg LA, Taylor RK, Jensen GJ. 2017. Architecture of the Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus machine revealed by electron cryotomography. Nat Microbiol 2:16269. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.269. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomassin JL, Santos Moreno J, Guilvout I, Tran Van Nhieu G, Francetic O. 2017. The trans-envelope architecture and function of the type 2 secretion system: new insights raising new questions. Mol Microbiol 105:211–226. 10.1111/mmi.13704. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosal D, Kim KW, Zheng H, Kaplan M, Vogel JP, Cianciotto NP, Jensen GJ. 2019. In vivo structure of the Legionella type II secretion system by electron cryotomography. bioRxiv 10.1101/525063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Jensen GJ. 2006. In situ structure of the complete Treponema primitia flagellar motor. Nature 442:1062–1064. 10.1038/nature05015. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg HC. 2003. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem 72:19–54. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macnab RM. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:77–100. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DePamphilis ML, Adler J. 1971. Fine structure and isolation of the hook-basal body complex of flagella from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 105:384–395. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stallmeyer MJ, Aizawa S, Macnab RM, DeRosier DJ. 1989. Image reconstruction of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol 205:519–528. 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Francis NR, Sosinsky GE, Thomas D, DeRosier DJ. 1994. Isolation, characterization and structure of bacterial flagellar motors containing the switch complex. J Mol Biol 235:1261–1270. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1079. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas DR, Morgan DG, DeRosier DJ. 1999. Rotational symmetry of the C ring and a mechanism for the flagellar rotary motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:10134–10139. 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10134. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki H, Yonekura K, Namba K. 2004. Structure of the rotor of the bacterial flagellar motor revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle image analysis. J Mol Biol 337:105–113. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.034. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas DR, Francis NR, Xu C, DeRosier DJ. 2006. The three-dimensional structure of the flagellar rotor from a clockwise-locked mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 188:7039–7048. 10.1128/JB.00552-06. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Lin T, Botkin DJ, McCrum E, Winkler H, Norris SJ. 2009. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J Bacteriol 191:5026–5036. 10.1128/JB.00340-09. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kudryashev M, Cyrklaff M, Wallich R, Baumeister W, Frischknecht F. 2010. Distinct in situ structures of the Borrelia flagellar motor. J Struct Biol 169:54–61. 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.08.008. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrusci P, Vergara-Irigaray M, Johnson S, Beeby MD, Hendrixson DR, Roversi P, Friede ME, Deane JE, Jensen GJ, Tang CM, Lea SM. 2013. Architecture of the major component of the type III secretion system export apparatus. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:99–104. 10.1038/nsmb.2452. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen S, Beeby M, Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Hendrixson DR, Briegel A, Li Z, Shi J, Tocheva EI, Müller A, Dobro MJ, Jensen GJ. 2011. Structural diversity of bacterial flagellar motors. EMBO J 30:2972–2981. 10.1038/emboj.2011.186. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beeby M, Ribardo DA, Brennan CA, Ruby EG, Jensen GJ, Hendrixson DR. 2016. Diverse high-torque bacterial flagellar motors assemble wider stator rings using a conserved protein scaffold. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E1917–E1926. 10.1073/pnas.1518952113. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin Z, Lin WT, Zhu S, Franco AT, Liu J. 2017. Imaging the motility and chemotaxis machineries in Helicobacter pylori by cryo-electron tomography. J Bacteriol 199:e00695-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaban B, Coleman I, Beeby M. 2018. Evolution of higher torque in Campylobacter-type bacterial flagellar motors. Sci Rep 8:97. 10.1038/s41598-017-18115-1. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan M, Ghosal D, Subramanian P, Oikonomou CM, Kjaer A, Pirbadian S, Ortega DR, Briegel A, El-Naggar MY, Jensen GJ. 2019. The presence and absence of periplasmic rings in bacterial flagellar motors correlates with stator type. eLife 8:e43487. 10.7554/eLife.43487. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu S, Nishikino T, Hu B, Kojima S, Homma M, Liu J. 2017. Molecular architecture of the sheathed polar flagellum in Vibrio alginolyticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:10966–10971. 10.1073/pnas.1712489114. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galán JE, Lara-Tejero M, Marlovits TC, Wagner S. 2014. Bacterial type III secretion systems: specialized nanomachines for protein delivery into target cells. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:415–438. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155725. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diepold A, Armitage JP. 2015. Type III secretion systems: the bacterial flagellum and the injectisome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370:20150020. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0020. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu B, Morado DR, Margolin W, Rohde JR, Arizmendi O, Picking WL, Picking WD, Liu J. 2015. Visualization of the type III secretion sorting platform of Shigella flexneri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1047–1052. 10.1073/pnas.1411610112. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu B, Lara-Tejero M, Kong Q, Galan JE, Liu J. 2017. In situ molecular architecture of the Salmonella type III secretion machine. Cell 168:1065–1074.e1010. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner S, Königsmaier L, Lara-Tejero M, Lefebre M, Marlovits TC, Galán JE. 2010. Organization and coordinated assembly of the type III secretion export apparatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:17745–17750. 10.1073/pnas.1008053107. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park D, Lara-Tejero M, Waxham MN, Li W, Hu B, Galán JE, Liu J. 2018. Visualization of the type III secretion mediated Salmonella-host cell interface using cryo-electron tomography. eLife 7:e39514. 10.7554/eLife.39514. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ide T, Laarmann S, Greune L, Schillers H, Oberleithner H, Schmidt MA. 2001. Characterization of translocation pores inserted into plasma membranes by type III-secreted Esp proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell Microbiol 3:669–679. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00146.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Low HH, Gubellini F, Rivera-Calzada A, Braun N, Connery S, Dujeancourt A, Lu F, Redzej A, Fronzes R, Orlova EV, Waksman G. 2014. Structure of a type IV secretion system. Nature 508:550–553. 10.1038/nature13081. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frick-Cheng AE, Pyburn TM, Voss BJ, McDonald WH, Ohi MD, Cover TL. 2016. Molecular and structural analysis of the Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system core complex. mBio 7:e02001-15. 10.1128/mBio.02001-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chetrit D, Hu B, Christie PJ, Roy CR, Liu J. 2018. A unique cytoplasmic ATPase complex defines the Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion channel. Nat Microbiol 3:678–686. 10.1038/s41564-018-0165-z. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosal D, Chang YW, Jeong KC, Vogel JP, Jensen GJ. 2018. Molecular architecture of the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. bioRxiv 10.1101/312009. [DOI]

- 61.Chang YW, Shaffer CL, Rettberg LA, Ghosal D, Jensen GJ. 2018. In vivo structures of the Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system. Cell Rep 23:673–681. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.085. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ensminger AW. 2016. Legionella pneumophila, armed to the hilt: justifying the largest arsenal of effectors in the bacterial world. Curr Opin Microbiol 29:74–80. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.11.002. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aoki SK, Pamma R, Hernday AD, Bickham JE, Braaten BA, Low DA. 2005. Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science 309:1245–1248. 10.1126/science.1115109. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aoki SK, Malinverni JC, Jacoby K, Thomas B, Pamma R, Trinh BN, Remers S, Webb J, Braaten BA, Silhavy TJ, Low DA. 2008. Contact-dependent growth inhibition requires the essential outer membrane protein BamA (YaeT) as the receptor and the inner membrane transport protein AcrB. Mol Microbiol 70:323–340. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06404.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruhe ZC, Nguyen JY, Xiong J, Koskiniemi S, Beck CM, Perkins BR, Low DA, Hayes CS. 2017. CdiA effectors use modular receptor-binding domains to recognize target bacteria. mBio 8:e00290-17. 10.1128/mBio.00290-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruhe ZC, Subramanian P, Song K, Nguyen JY, Stevens TA, Low DA, Jensen GJ, Hayes CS. 2018. Programmed secretion arrest and receptor-triggered toxin export during antibacterial contact-dependent growth inhibition. Cell 175:921–933.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.033. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. 2010. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19520–19524. 10.1073/pnas.1012931107. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Basler M, Pilhofer M, Henderson GP, Jensen GJ, Mekalanos JJ. 2012. Type VI secretion requires a dynamic contractile phage tail-like structure. Nature 483:182–186. 10.1038/nature10846. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bönemann G, Pietrosiuk A, Mogk A. 2010. Tubules and donuts: a type VI secretion story. Mol Microbiol 76:815–821. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07171.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang YW, Rettberg LA, Ortega DR, Jensen GJ. 2017. In vivo structures of an intact type VI secretion system revealed by electron cryotomography. EMBO Rep 18:1090–1099. 10.15252/embr.201744072. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rapisarda C, Cherrak Y, Kooger R, Schmidt V, Pellarin R, Logger L, Cascales E, Pilhofer M, Durand E, Fronzes R. 2018. In situ and high-resolution cryo-EM structure of the type VI secretion membrane complex. bioRxiv 10.1101/441683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Shikuma NJ, Pilhofer M, Weiss GL, Hadfield MG, Jensen GJ, Newman DK. 2014. Marine tubeworm metamorphosis induced by arrays of bacterial phage tail-like structures. Science 343:529–533. 10.1126/science.1246794. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Medeiros JM, Böck D, Pilhofer M. 2018. Imaging bacteria inside their host by cryo-focused ion beam milling and electron cryotomography. Curr Opin Microbiol 43:62–68. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.12.006. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Böck D, Medeiros JM, Tsao HF, Penz T, Weiss GL, Aistleitner K, Horn M, Pilhofer M. 2017. In situ architecture, function, and evolution of a contractile injection system. Science 357:713–717. 10.1126/science.aan7904. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]