Abstract

Objective

To examine the predictive validity of a TUG test for falls risk, quantified using body-worn sensors (QTUG) in people with Parkinson's Disease (PD). We also sought to examine the inter-session reliability of QTUG sensor measures and their association with the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score.

Approach

A six-month longitudinal study of 15 patients with Parkinson’s disease. Participants were asked to complete a weekly diary recording any falls activity for six months following baseline assessment. Participants were assessed monthly, using a Timed Up and Go test, quantified using body-worn sensors, placed on each leg below the knee.

Main results

The results suggest that the QTUG falls risk estimate recorded at baseline is 73.33% (44.90, 92.21) accurate in predicting falls within 90 days, while the Timed Up and Go time at baseline was 46.67% (21.27, 73.41) accurate. The Timed Up and Go time and QTUG falls risk estimate were strongly correlated with UPDRS motor score. Fifty-two of 59 inertial sensor parameters exhibited excellent inter-session reliability, five exhibited moderate reliability, while two parameters exhibited poor reliability.

Significance

The results suggest that QTUG is a reliable tool for the assessment of gait and mobility in Parkinson’s disease and, furthermore, that it may have utility in predicting falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: Falls, Parkinson’s disease, sensors, reliability

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, which has significant deleterious effects on gait and balance. The prevalence of PD has been estimated as 0.3% in industrialised countries.1 Prevalence increases with age to 1% in the over 60s and increases further in the over 80s in the over 80s. The costs associated with PD are significant with costs in the US alone estimated to be $23Bn per year,2,3 and with costs in the UK reported to be between £449M and £3.3Bn per year.4

People with PD are at much higher risk of falls than the general population;5 they are also twice as likely to fall as patients with other neurological conditions,6,7 with falls occurring more frequently especially when the disease becomes advanced. It has been estimated that 38–68% of patients with PD will fall at some point during the course of their disease.5,8–10 Despite this high prevalence, current clinical tools for assessment may not provide sufficient accuracy and reliability for assessment of this risk. Current clinical evidence suggests that the best predictor of a fall in patients with PD is the occurrence of a fall in the preceding year.11 However, the use of history of falls relies on participant recall which can be flawed and unreliable, particularly in populations prone to cognitive decline. Additionally, data on historical falls in patients with PD do not provide any information on the increased risk of a first fall, brought about by disease progression or comorbidities12 in the intervening period. PD is usually assessed in a clinical environment using clinical scales, such as the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)13 which can be subjective, with significant variation in administration. The use of inertial sensors may allow identification of mobility deficits which are not apparent using traditional clinical tools.

The Timed Up and Go (TUG) test is a standard test of mobility, widely used to screen for gait and balance issues in older adults.14–16 The TUG test is also used to assess balance, mobility and risk of falls in Parkinson’s.12 The time to complete the test (TUG time) has been shown to have moderate predictive ability for falls in community-dwelling older adults17,18 and has been shown to be modestly predictive of falls in patients with PD.12 However, the TUG test can also be subjective and can vary widely in its implementation. The TUG time itself does not provide any indication or additional information on specific mobility impairments that can be associated with Parkinson’s or risk of falls.

Previous research has demonstrated that a TUG test quantified with inertial sensors (QTUG) is reliable in the measurement of gait and mobility,19 as well as in its accuracy in the assessment of falls in community-dwelling older adults.20 The utility of the QTUG tool in examining gait, mobility and risk of falls in PD has not yet been examined. Several previous studies have also examined the value of an instrumented TUG test in assessment of gait and mobility in Parkinson’s.21–23 Similarly, a number of studies have used body-worn sensors to assess the risk of falls in patients with PD. Weiss et al.24 found that an accelerometer worn for three days on the lower back discriminated patients with PD with a history of falls from patients with PD with no history of falls. To our knowledge, there has not yet been a prospective study on the validity of body-worn sensors for prediction of falls in patients with PD. Additionally, to our knowledge, the inter-session reliability of body-worn sensor measures obtained during a TUG test has not been examined in patients with PD.

This study aimed to examine the utility of a quantified TUG in the assessment of gait and mobility in patients with PD. Specifically, we aimed to examine the association of part III of the UPDRS scale (referred to as UPDRS motor scores) with the risk of falls and frailty estimates (FEs) as well as the TUG time. We also aimed to examine the predictive validity of QTUG for falls in Parkinson’s patients, using prospective falls follow-up data collected from weekly fall diaries. We also aimed to determine the inter-session reliability, in this population, of the quantitative gait and mobility measures calculated for each QTUG test.

Data set

We report a single-site longitudinal study of patients with PD. A total of 16 participants were recruited from the OSF HealthCare-Illinois Neurological Institute (Peoria, IL, USA). Sensor data were not available for one participant, leaving 15 participants for analysis (5 female, mean age 67.3 ± 7.1). Data are summarised in Table 1. Patients were assessed over a six-month period. QTUG assessments were conducted on a monthly basis, following an initial baseline assessment. A total of 94 QTUG recordings were available for the 15 participants. Participants were evaluated three times using the UPDRS part III: at baseline, 90 days and 180 days.

Inclusion criteria: able to provide written informed consent, aged 40 to 80, idiopathic PD (meeting UK Brain Bank Criteria), responsive to Levodopa for at least four years, mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score greater than 22 and able to walk at least 3 m independently.

Exclusion criteria: atypical Parkinsonism, Hoehn and Yahr stage 5, MMSE 21 or less, use of assisted device for ambulation, co-morbidities affecting balance: severe neuropathy, weakness, bilateral hip replacement, syncopal episodes causing falls, diagnosed with lumbar radiculopathy, spinal stenosis or any other back conditions with the potential to affect fall behaviour, drug abuse or alcoholism.

Table 1.

Clinical data for each participant at baseline, as well as number of falls recorded per participant and UPDRS scores at baseline, 90 days and 180 days.

| ID | Age (years) | Gender | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | No. of falls | UPDRS baseline | UPDRS day 90 | UPDRS day 180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 81 | M | 76.7 | 177.8 | 0 | 33 | 28 | |

| 2 | 65 | M | 87.1 | 177.8 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 15 |

| 3 | 65 | M | 110.2 | 188.0 | 0 | 13 | 16 | 22 |

| 4 | 71 | M | 88.0 | 180.3 | 1 | 9 | 22 | 18 |

| 5 | 67 | M | 88.5 | 182.9 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | 59 | M | 78.5 | 165.1 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3 |

| 7 | 67 | M | 88.5 | 172.7 | 1 | 20 | 15 | 27 |

| 8 | 75 | F | 85.7 | 154.9 | 0 | 20 | 21 | 30 |

| 9 | 72 | F | 88.9 | 172.7 | 11 | 11 | 39 | |

| 10 | 56 | M | 70.3 | 172.7 | 1 | 15 | 10 | 10 |

| 11 | 73 | M | 81.6 | 175.3 | 30 | 14 | 18 | 14 |

| 12 | 54 | F | 65.8 | 165.1 | 1 | 11 | 15 | 25 |

| 13 | 67 | F | 56.7 | 157.5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 24 |

| 14 | 69 | M | 91.6 | 185.4 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| 15 | 69 | F | 45.8 | 165.1 | 127 | 38 | 28 |

UPDRS: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

All patients were required to provide informed consent. Ethical approval was received from the Peoria Institutional Review Board.

Methods

Fall data

Participants were asked to complete a weekly diary recording any falls activity, for six months following baseline assessment. The diary was collected on a weekly basis by a researcher and collated for later analysis. Each diary captured information about the frequency, timing, location and severity of each fall.

Gait and mobility assessment

The gait and mobility of each participant were assessed, during the TUG test, on a monthly basis, using an inertial sensor and software system (Kinesis QTUG™, Kinesis Health Technologies, Dublin, Ireland). Sensors were placed on each leg, below the knee, while participants completed the TUG test. Each sensor contained a tri-axial gyroscope and a tri-axial accelerometer. Sensor data were streamed via Bluetooth to a tablet computer, for subsequent analysis. The software measures 59 gait and mobility parameters during the TUG test, including the time to complete the test (TUG time), a statistical estimate of the patient’s risk of having a fall, known as the falls risk estimate (FRE),20 as well as a statistical estimate of the patient’s frailty level (known as the FE).25 Both the FRE and FE measures are generated from statistical models of falls risk and frailty, based on large samples of community-dwelling older adults. Both measures are calculated using parameters derived from inertial sensor data recorded during the TUG test, as well as demographics data and clinical fall risk factors.

TUG test protocol

In completing a TUG test, a participant gets up from a chair, walks 3 m, turns 180° at a designated spot, walks back to the seat and re-seats. Each participant was asked to complete the TUG test ‘as fast as safely possible’, using a standard chair with armrest. The test timer was started by the clinician the moment the clinician said ‘go’ and stopped when the participant’s back touched the chair. Each participant was given time to become familiar with the test, and the test was demonstrated to them beforehand.

Statistical analysis

Linear mixed effect models were used to examine the association of UPDRS with FRE, FE and TUG time. Assessment session and patient ID were included as random factors. In addition, the correlation of each QTUG measure with UPDRS motor scores at baseline was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

The predictive validity of the FRE and FE measures was calculated using standard metrics. Accuracy (Acc) is defined as the proportion of participants correctly classified by the software as being a ‘faller’ or ‘non-faller’ (a faller is defined as having one or more falls in the follow-up period); sensitivity (Sens) is defined as the proportion of participants labelled as fallers correctly classified by the software as such; specificity (Spec) is defined as the proportion of the non-fallers correctly identified by the software. Positive predictive value is defined as the proportion of participants the software classified as fallers, who are correctly classified; negative predictive value is the proportion of those participants the classified by the software as non-fallers, who were classified correctly. A binomial proportion confidence interval was used to estimate confidence intervals. A 70% threshold was used for the FRE and FE, as the cut-off value to identify participants at high risk of falls.

The predictive validity of the TUG time was also calculated, in order to provide a comparator for the results. A cut-off time of 11.5 s was chosen for high risk of falls, based on previously reported research on predicting falls in patients with PD.12

Inter-session reliability across multiple weeks was examined using the intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC(2,k).26 An ICC value of 0.7 or greater was considered to demonstrate excellent reliability, while 0.4–0.7 was moderately reliable. ICC values less than 0.4 were considered poor. Reliability statistics were calculated using all available recordings for each participant, and 95% confidence intervals for each measure are provided.

Statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (version 9.1, Mathworks, Natick, VA, USA).

Results

UPDRS results

All patients received a cognitive assessment using MMSE at baseline and at 180 days, mean MMSE at baseline was 28.42 ± 1.92. The mean UPDRS-part III score at baseline was 14.3 ± 9.5.

Decrease of UPDRS part III (motor) score of greater than or equal to 5 points is considered clinically significant after six months.27 Three of 13 patients demonstrated clinically significant decrease at six months. Schulman et al.28 reported a minimal clinically important difference (CID) of 2.5 for UPRDS motor score, with 5.2 for moderate and 10.8 for large CID. At 90 days 12 patients exhibited an increase in UPDRS motor score of more than 2.5, while six patients exhibited a decrease in UPDRS motor score of more than 2.5. At 180 days 11 patients showed an increase of more than 2.5 in UPDRS motor score, while 4 patients showed a decrease in UPRDS motor score of more than 2.5.

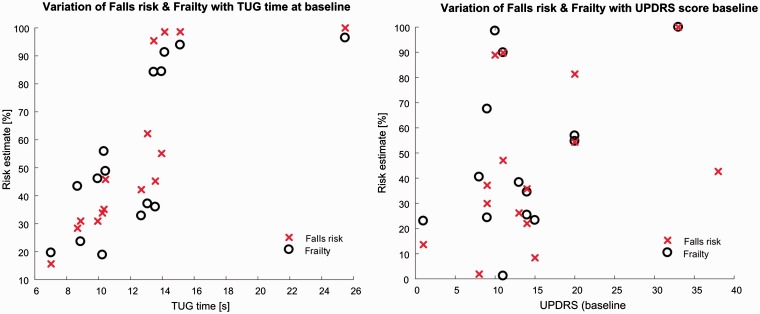

At baseline, the TUG time was significantly correlated with the QTUG FRE (ρ = 0.77, p < 0.01), TUG time at baseline was also significantly correlated with QTUG FE (ρ = 0.68, p < 0.01) (see Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

(a) Variation of falls risk estimate (FRE) and frailty estimate (FE) at baseline with TUG time at baseline. TUG time at baseline is significantly correlated with FRE and FE (b) variation of FRE and FE at baseline with UPDRS motor score at baseline. FRE and FE at baseline are significantly correlated with UPDRS motor score at baseline.

UPDRS: Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; TUG: TUG: Timed Up and Go.

The UPDRS motor score at baseline was significantly correlated with QTUG FRE (ρ = 0.60, p < 0.05); the baseline UPDRS motor score was not significantly correlated with the QTUG FE (ρ = 0.41, p = 0.13) (see Figure 1(b)).

A linear mixed effects, with FRE as a fixed effect, and assessment session and patient ID as random factors demonstrated that FRE was significantly associated with UPDRS motor score across patients and assessments. A linear mixed effect model, with FE as a fixed effect, and assessment session and patient ID as random factors showed that FE was significantly associated with UPDRS motor score across patients and assessments. Similarly, a linear mixed effect model found a significant association between TUG time and UPDRS. In addition, the correlation of the UPDRS baseline score with TUG time at baseline was significant (ρ = 0.62, p < 0.05).

Falls risk assessment

Weekly fall diaries were available for 15 participants. Complete follow-up data at 180 days were available for 12 of 15 participants, while complete follow-up data at 90 days were available for all 15 participants. At 90 days, 4 of 15 participants had experienced a fall, while at 180 days, 8 of the 12 participants remaining had experienced a fall. A total of 181 falls were recorded; the distribution of falls per participant is detailed in Table 1. The baseline QTUG FRE was 73.33% (44.90, 92.21) accurate in predicting falls within 90 days, while the baseline FE and TUG time were 60.00% (32.29, 83.67) and 46.67% (21.27, 73.41) accurate, respectively.

The baseline FRE was 58.33% (27.67, 84.83) accurate in predicting falls at 180 days, while the baseline FE and TUG time were 41.67% (15.17, 72.33) and 58.33% (27.67, 84.83) accurate, respectively. Detailed performance results for the predictive validity for falls are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance of TUG time, FRE and frailty estimate in predicting fall within 90 and 180 days in patients with PD.

| 90-day follow-up |

180-day follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (fallers/ total) | 4/15 |

8/12 |

||||

| FRE | Frailty | TUG time | FRE | Frailty | TUG time | |

| Acc (%) | 73.33 | 60.00 | 46.67 | 58.33 | 41.67 | 58.33 |

| Sens (%) | 50.00 | 25.00 | 50.00 | 37.50 | 25.00 | 62.50 |

| Spec (%) | 81.82 | 72.73 | 45.45 | 100.00 | 75.00 | 50.00 |

| PPV (%) | 50.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 100.00 | 66.67 | 71.43 |

| NPV (%) | 81.82 | 72.73 | 71.43 | 44.44 | 33.33 | 40.00 |

NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; TUG: Timed Up and Go; FRE: falls risk estimate; PD: Parkinson’s disease; Acc: accuracy; Sens: sensitivity; Spec: specificity.

Inter-session reliability

The reliability of 59 inertial sensor-derived parameters calculated for each TUG test was examined across an average of six weekly sessions (see Table 3). The QTUG FRE and FEs demonstrated excellent inter-session reliability (ICC > 0.7). The TUG time and all temporal and spatial gait parameters also demonstrated excellent inter-session reliability. Six of eight gait variability parameters demonstrated excellent reliability, while the remaining two demonstrated moderate reliability (0.4 < ICC < 0.7). Three of four gait symmetry parameters demonstrated excellent reliability, while the fourth demonstrated poor reliability (ICC < 0.4). For the turn parameters, three of seven demonstrated excellent reliability, three moderate and one poor reliability. All angular velocity parameters demonstrated excellent inter-session reliability.

Table 3.

Inter-session reliability measured using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC(2,k)), with 95% confidence intervals for each inertial sensor derived parameter.

| Variable name | ICC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Falls risk estimate (%) | 0.86 | (0.71–0.94) |

| Frailty estimate (%) | 0.91 | (0.82–0.97) |

| Temporal gait parameters | ||

| TUG test time (s) | 0.77 | (0.53–0.91) |

| Time to stand (s) | 0.71 | (0.41–0.89) |

| Time to sit (s) | 0.81 | (0.61–0.93) |

| Mean stance time (s) | 0.80 | (0.59–0.92) |

| Mean swing time (s) | 0.89 | (0.77–0.96) |

| Mean stride time (s) | 0.85 | (0.70–0.94) |

| Mean step time (s) | 0.85 | (0.70–0.94) |

| Mean double support (%) | 0.79 | (0.58–0.92) |

| Mean single support (%) | 0.84 | (0.68–0.94) |

| Cadence (steps/min) | 0.78 | (0.55–0.91) |

| Number of gait cycles | 0.78 | (0.55–0.91) |

| Number of steps | 0.75 | (0.49–0.90) |

| Walk time (s) | 0.81 | (0.61–0.92) |

| Gait variability parameters | ||

| CV stride velocity (%) | 0.89 | (0.77–0.96) |

| CV stride length (%) | 0.45 | (0–0.79) |

| Swing time variability (%) | 0.79 | (0.56–0.92) |

| Double support variability (%) | 0.80 | (0.59–0.92) |

| Stance time variability (%) | 0.78 | (0.56–0.92) |

| Step time variability (%) | 0.47 | (0–0.79) |

| Stride time variability (%) | 0.75 | (0.49–0.90) |

| Single support variability (%) | 0.74 | (0.47–0.90) |

| Gait symmetry parameters | ||

| Step time asymmetry (%) | 0.39 | (0–0.76) |

| Swing time asymmetry (%) | 0.79 | (0.58–0.92) |

| Stride time asymmetry (%) | 0.79 | (0.57–0.92) |

| Stance time asymmetry (%) | 0.78 | (0.55–0.91) |

| Spatial gait parameters | ||

| Mean stride velocity (cm/s) | 0.88 | (0.76–0.95) |

| Mean stride length (cm/s) | 0.89 | 0.78–0.96) |

| Turn parameters | ||

| Return from turn time (s) | 0.76 | (0.52–0.91) |

| Turn mid-point time (s) | 0.76 | (0.52–0.91) |

| Turning time (s) | 0.58 | (0.14–0.84) |

| Turn magnitude (deg/s) | 0.51 | (0–0.81) |

| Walk ratio | 0.85 | (0.69–0.94) |

| Number of strides in turn | 0.30 | (0–0.73) |

| Ratio strides/turning time | 0.42 | (0–0.77) |

| Angular velocity parameters | ||

| Magnitude range at mid-swing points (deg/s) | 0.73 | (0.45–0.89) |

| Min Z-axis ang. vel. × Height (deg.m/s) | 0.93 | (0.87–0.97) |

| Max X-axis ang. vel. × height (deg.m/s) | 0.93 | (0.87–0.97) |

| Max X-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.93 | (0.85–0.97) |

| Min Z-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.92 | (0.84–0.97) |

| Mean Y-axis ang. vel. × height (deg.m/s) | 0.91 | (0.83–0.97) |

| Mean Z-axis ang. vel. × Height (deg.m/s) | 0.91 | (0.83–0.97) |

| Mean X-axis ang. vel. × Height (deg.m/s) | 0.90 | (0.80–0.96) |

| Mean Y-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.90 | (0.80–0.96) |

| Mean Z-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.90 | (0.79–0.96) |

| Max Z-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.84 | (0.68–0.94) |

| Min X-axis ang. vel. × Height (deg.m/s) | 0.83 | (0.66–0.93) |

| Mean X-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.89 | (0.77–0.96) |

| Max Y-axis ang. vel. × height (deg.m/s) | 0.87 | (0.75–0.95) |

| Magnitude mean at mid-swing points (deg/s) | 0.87 | (0.74–0.95) |

| Max Z-axis ang. vel. × height (deg.m/s) | 0.87 | (0.74–0.95) |

| CV X-axis ang. vel. (%) | 0.87 | (0.73–0.95) |

| Max Y-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.85 | (0.70–0.94) |

| CV Y-axis ang. vel. (%) | 0.79 | (0.58–0.92) |

| Min Y-axis ang. vel. × Height (deg.m/s) | 0.78 | (0.56–0.92) |

| CV Z-axis ang. vel. (%) | 0.76 | (0.52–0.91) |

| Min Y-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.76 | (0.51–0.91) |

| Min X-axis ang. vel. (deg/s) | 0.81 | (0.61–0.92) |

TUG: Timed Up and Go; CV: coefficient of variation.

Discussion

We report a longitudinal study of body-worn sensor data obtained during a TUG test from participants with PD. We have found that sensor-derived measures of falls risk and frailty are strongly associated with UPDRS across multiple assessments. We also report the predictive accuracy of these measures in predicting falls in patients with PD, using prospective follow-up data obtained from weekly fall diaries. In addition, we examine the inter-session reliability of body-worn sensor measures of gait and mobility, obtained, during the TUG test in patients with PD.

Results suggest that the TUG time, FRE and FE are strongly correlated with the UPDRS score at baseline; in addition, linear mixed effect models showed there is a strong association between TUG time, falls risk and FEs with UPDRS scores taken at baseline, 90 days and 180 days. This suggests that a model based on inertial sensors measures of movement could be used as a surrogate measure of disease progression in patients with PD.

The analysis of the TUG time, falls risk and FEs at 90 days found that the QTUG FRE was markedly more accurate than the TUG time in predicting falls (73.33% compared to 46.67%). Similarly, the FE was more accurate in predicting falls than the TUG time (60.00% compared to 46.67%). Examining follow-up data at 180 days, all metrics demonstrated lower accuracy in predicting falls; the QTUG FRE score and TUG time were equally accurate (58.33%), while the FE was less accurate (41.67%). The reduction in accuracy in all metrics between 90 and 180 days follow-up may be due to the lower number of patients with complete follow-up data available at 180 days (12 compared to 15 at 90 days) or may be a feature of this population, in that forecasting of falls in patients with PD is less accurate over a longer time window. The reported results provide a statistically independent validation of the QTUG FRE and FE for use in prediction of falls in patients with PD.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to provide an objective statistical risk score for falls in patients with PD. An evidence-based risk profile for falls in patients with PD, based on objective measures of mobility, could contribute to standardised assessment of falls risk in patients with PD. We report a prospective validation of this using fall diaries, collected weekly which are considered more reliable than other methods of collecting falls outcome data. The portable nature of the solution could allow assessment outside of traditional clinical environments such as the home or community.

On average, each study participant was assessed using QTUG seven times; once at baseline and then once a month for six months. Examining the inter-session test–retest reliability of the gait and mobility parameters derived from the inertial sensor data from each TUG test across all seven sessions found that 52 of 59 parameters exhibited excellent reliability, while five exhibited moderate reliability and two parameters exhibited poor reliability. It is noteworthy that the TUG time, FRE and FE all exhibited excellent reliability, supporting their use in the longitudinal assessment of PD. Given the nature of the TUG test, the turn strategy (e.g. turn left or right, pivot turn or multiple step), a participant chooses while executing the turn portion of the TUG test, has a major bearing on the reliability of the turn parameters, i.e. if a participant chose to vary their turn strategy between assessments. Turn strategy can also affect the reliability of the calculated gait variability and gait symmetry parameters and could perhaps explain the lower reliability values obtained for some of these parameters. In addition, the short distance of the TUG test could also affect the reliability of some parameters just as gait variability and gait symmetry. In general, the strong results reported for test–retest reliability suggest that QTUG could be a valuable tool for ongoing assessment of gait and mobility in PD.

Study limitations

A major limitation of the present study is the small size of the data set used; the reported associations with UPDRS motor scores and results for prediction of falls would need to be confirmed through a much larger population sample. While the sample is very small, the longitudinal study design and use of prospective weekly fall diaries are in line with international best practice. However, it should be noted that self-reported data on falls can be difficult to acquire and can be inaccurate, even when diaries are collected on a weekly basis.

Conclusions

The results suggest that QTUG may be a reliable tool for longitudinal assessment of gait and mobility in patients with PD, and furthermore, it may have utility in predicting falls in patients with PD. Future work will seek to validate the present results on a larger data set, as well as to stratify participants based on disease level and examine how QTUG can be used to predict falls in those at different stages of the disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the help and support of the staff of the Illinois Neurological Institute, and the participants involved in this study.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Author BRG is a director of Kinesis Health Technologies Ltd, a company with a license to commercialise this technology.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study was provided by Care Innovations LLC who are a shareholder in Kinesis Health Technologies.

Guarantor

BRG

Contributorship

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.de Lau LML, Breteler MMB. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huse DM, Schulman K, Orsini L, et al. Burden of illness in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2005; 20: 1449–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, et al. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the United States. Mov Disord 2013; 28: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Findley LJ. The economic impact of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007; 13(Supplement): S8–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloem BR, Hausdorff JM, Visser JE, et al. Falls and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a review of two interconnected, episodic phenomena. Mov Disord 2004; 19: 871–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolze H, Klebe S, Zechlin C, et al. Falls in frequent neurological diseases. J Neurol 2004; 251: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalilani L, Asgharnejad M, Palokangas T, et al. Comparing the incidence of falls/fractures in Parkinson’s disease patients in the US population. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0161689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloem BR, Grimbergen YA, Cramer M, et al. Prospective assessment of falls in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 2001; 248: 950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudzińska M, Bukowczan S, Stożek J, et al. The incidence and risk factors of falls in Parkinson disease: prospective study. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2013; 47: 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood SJ, Ramsdell CD, Mullen TJ, et al. Transient cardio-respiratory responses to visually induced tilt illusions. Brain Res Bull 2000; 53: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickering RM, Grimbergen YAM, Rigney U, et al. A meta-analysis of six prospective studies of falling in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007; 22: 1892–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocera JR, Stegemöller EL, Malaty IA, et al. Using the Timed Up & Go test in a clinical setting to predict falling in Parkinson's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2013; 94: 1300–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaker C, Marinus J, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Systematic evaluation of rating scales for impairment and disability in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2002; 17: 867–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathias S, Nayak U, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: the “get-up and go” test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67: 387–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go test. Phys Ther 2000; 80: 896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, et al. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2014; 1: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrane G, Joakimsen R, Thornquist E. The association between timed up and go test and history of falls: the Tromso study. BMC Geriatrics 2007; 7: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith E, Walsh L, Doyle J, et al. The reliability of the quantitative timed up and go test (QTUG) measured over five consecutive days under single and dual-task conditions in community dwelling older adults. Gait Post 2016; 43: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene BR, Redmond SJ, Caulfield B. Fall risk assessment through automatic combination of clinical fall risk factors and body-worn sensor data. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2016; 21: 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salarian A, Horak FB, Zampieri C, et al. iTUG, a sensitive and reliable measure of mobility. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2010; 18: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani B, Jiménez MC, Vingerhoets FJG, et al. On-shoe wearable sensors for gait and turning assessment of patients with Parkinson's disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2013; 60: 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss A, Herman T, Plotnik M, et al. Can an accelerometer enhance the utility of the Timed Up & Go test when evaluating patients with Parkinson's disease? Med Eng Phys 2010; 32: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss A, Herman T, Giladi N, et al. Objective assessment of fall risk in Parkinson's disease using a body-fixed sensor worn for 3 days. PLoS One 2014; 9: e96675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene BR, Doheny EP, O’Halloran A, et al. Frailty status can be accurately assessed using inertial sensors and the TUG test. Age Ageing 2014; 43: 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86: 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrag A, Sampaio C, Counsell N, et al. Minimal clinically important change on the unified Parkinson's disease rating scale. Mov Disord 2006; 21: 1200–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shulman LM, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, et al. The clinically important difference on the unified parkinson's disease rating scale. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]